Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to

Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

Pingkan C. B. Rumondor

1a

, Eilien Rosalie

1b

, Syifa Fauziah

1c

, Adriana S. Ginanjar

2d

,

Claudia Chiarolanza

3e

and Ashley K. Randall

4f

1

Department of Psychology, Bina Nusantara University, Jl. Kemanggisan Ilir III No. 45 Kemanggisan, Jakarta, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Psychology, University of Indonesia, Kampus Baru UI Depok, Jawa Barat 16424, Indonesia

3

Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, and Health Studies, Sapienza - University of Rome,

via dei Marsi, 7800185, Rome, Italy

4

Counseling and Counseling Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona, 85287-0811, U.S.A.

claudia.chiarolanza@uniroma1.it, Ashley.K.Randall@asu.edu

Keywords: Stress, Covid-19 Quarantine, Romantic Relationship.

Abstract: COVID-19 was declared as a public health emergency of international concern on January 30, 2020.

Currently, this virus has spread to more than 193 countries in the world, including Indonesia. The spread of

the COVID-19 virus continues to negatively impact individuals’ health, economy, psychological well-being,

and social and family relationships. Although COVID-19 is considered an international concern, individual

perception, and reaction toward a stressor vary across countries. As such, this study aimed to highlight how

individuals living in Indonesia perceived stress related to the early phases of COVID-19. We examine this

across three contexts: perceived individual, interpersonal (i.e., their romantic partner’s stress), and community

stressors. Using inductive thematic analysis, qualitative data collected via an online survey from 422

individuals in a romantic relationship from March to June 2020 showed that participants’ answers could be

clustered to ten overarching themes. Interestingly, one theme describing an absence of stress or positive stress

emerged in the analysis. Results suggested that participants were experiencing vulnerability related to social

restriction due to the COVID-19 situation, offering an insight into future culture-appropriate practices related

to stress and coping responses for individuals in romantic relationships.

1 INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the

2019 coronavirus (COVID-19) a public health

emergency of international concern; indeed, the virus

has spread to more than 190 countries worldwide.

Until August 13, 2021, COVID-19 cases have

reached 205,338,159 cases globally, and the death

cases have reached 4,333,094 deaths (WHO, 2020).

These data show that the COVID-19 virus can spread

easily, has taken many lives, and is a problem

worldwide.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0778-929X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1407-8592

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7864-2885

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6806-8456

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8726-4724

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3794-4163

Indonesia is currently dealing with the COVID-19

pandemic. As of August 11, 2021, COVID-19 cases

in Indonesia have reached 3,749,446 cases, and the

death cases have reached 112,198 deaths (WHO

Indonesia, 2021). COVID-19 cases in Indonesia have

spread in 34 provinces and 514 districts/cities in

Indonesia (WHO Indonesia, 2021). The spread of the

COVID-19 virus in Indonesia is happening rapidly in

various parts, which were classified as regional

categories related to the spread of COVID-19, the

high-risk areas marked with a red zone, medium risk

areas marked with an orange zone. Regions marked

Rumondor, P., Rosalie, E., Fauziah, S., Ginanjar, A., Chiarolanza, C. and Randall, A.

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0010752800003112

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences (ICE-HUMS 2021), pages 403-420

ISBN: 978-989-758-604-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

403

as an orange zone reflect several cases of COVID-19

with some local transmission. Regions marked as a

red zone reflect COVID-19 cases in one or more

clusters with a high increase in cases. In red zones,

strict health protocols are needed, such as closing

schools, places of worship, and businesses. In fact,

several provinces in Indonesia were in a red zone in

March 2020, such as Sumatra, Sulawesi, East Nusa

Tenggara, Maluku, Lampung, Kalimantan, West

Java, DKI Jakarta, DI Yogyakarta, Banten and Bali

(Satuan Tugas Penanganan COVID-19, 2020).

Apart from the health-related concerns associated

with COVID-19, its impact can be found in

community-level restrictions. The increase in

COVID-19 cases in Indonesia has prompted the

Government to implement a new policy, Pembatasan

Sosial Berskala Besar (PSBB) or Large-Scale Social

Restrictions April 10, 2020. This new policy was

implemented to reduce the spread of COVID-19. In

this new policy, the Government limits office

activities to 25% and closes recreational areas, city

parks, sports facilities, and wedding reception venues

(Tempo, 2020). The Government also suggested that

teaching and learning activities be carried out online.

Some companies have decided to employ their

employees remotely for mutual safety. However,

some activities cannot be carried out online. In that

case, the Government asks the public to adhere to

health protocols such as wearing masks, social

distancing when in public places and on public

transportation, and washing one’s hands properly.

This policy was implemented to prevent COVID-19

from spreading.

The social restrictions imposed regarding the

COVID-19 have strains individuals, their

interpersonal relationships, and their communities.

Prior research on social isolation has shown its effects

on loneliness and increased depressive symptoms

(Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010). Moreover,

neuroscience studies of the long-term effects of social

restriction have shown that individuals may

experience several degenerative symptoms, including

neurocognitive and immune changes, fatigue, sleep

disturbances (Jacubowski et al., 2015; Pagel &

Choukèr, 2016). Indeed, being in quarantine and

lacking social interaction can disrupt a person’s

mood, cognitive performance, stress hormones, and

neurological activity (Cacioppo, Grippo, London,

Goossens, & Cacioppo, 2015; Friedler, Craser, &

McCullough, 2015). Additionally, given the

uncertainty individuals face with COVID-19, it is not

surprising that this uncertainty, ambiguity, and loss of

control, are known to trigger stress and emotional

distress, including symptoms of internalization, such

as anxiety and depression (Ensel & Lin, 1991;

Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981).

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined stress or

psychological stress as the result of a person’s

demands and existing resources to cope with such

demands. According to the transactional model of

stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), it is

essential to consider how individuals perceive and

appraise stressors and how their responses lead to

effective or maladaptive coping strategies. Thus,

understanding the perception of stressors can be a

valuable insight to inform stress management

strategies.

Social restrictions also strain one’s social

relationships, especially when quarantine with

romantic partners or family members. According to

Pietrabissa & Simpson (2020), the social restriction

can increase the risk of conflict and domestic

violence, increasing separation and divorce cases

during the COVID-19 pandemic in China (Pietrabissa

& Simpson, 2020). The divorce rate during the

COVID-19 pandemic has also increased in several

countries, such as China, Sweeden, the UK, and the

US (Savage, 2020). Meanwhile, in August 2020,

divorce cases in Indonesia had reached 306,688 cases

(Prihatin, 2020), comparable to the divorce rate in

2019 (480,618 cases). Despite the increasing divorce

rate from 2015, it is interesting that some divorce

cases in 2020 occurred in the COVID-19 red zone

(Permana, 2020). For example, in Brebes regency,

Central Java, Indonesia, a red zone, had reached

5.709 cases of divorce, of which 3.513 cases were

caused by economic factors (Kompas TV, 2021;

Wikanto, 2020). Financial factors can cause financial

stress and lower relationship satisfaction (Karademas

& Roussi, 2017). The data above implies that social

restrictions also have an impact on relationships.

In addition to the individual and relational effects

of COVID-19, associated restrictions can also impact

one’s community, broadly defined. One of the

COVID-19 pandemic impacts can be seen in the

economic sector, especially world financial markets.

The number of patients and deaths from COVID-19

increases daily, and the economy is becoming very

uncertain. Moreover, COVID-19 has affected 10% of

the stock index value in one day (Daube, 2021). The

market value of Europe, America, China, and Hong

Kong from January 1, 2020, to March 18, 2020,

experienced a significant decline and experienced a

drastic decline when COVID-19 approached its peak

in Western countries (Daube, 2021). The economic

crisis from COVID-19 impacts all countries exposed

to the COVID-19 virus, including Indonesia.

Companies that ultimately cannot operate so decide

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

404

to lay off their employees. Data from the Central

Statistics Bureau (Biro Pusat Statistik/BPS) shows an

increase in the Unemployment Rate (Tingkat

Pengangguran Terbuka/TPT) by 7,07% in August

2020 (Badan Pusat Statistik, 2020).

Notably, stress is subjective, irrespective of whom

it affects (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Moreover,

perceptions and responses to stress occur in a broader

context, such as tradition, norms, and cultural beliefs

(Bodenmann, 1995). Thus, to suggest a culturally

appropriate couple’s stress management, it is

essential to understand the couple’s perception of

stress. Recent studies have approached the

psychological implication of COVID-19 with

quantitative approaches, specifically examining

protective factors (e.g., demographic and

psychological traits) that can predict levels of

perceived stress (Flesia et al., 2020). However, given

the complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic,

qualitative data can capture individuals’ unique

perspectives on the impact of the pandemic (Wa-

Mbaleka & Costa, 2020), which can be utilized as a

basis for contextual stress management.

Taken together, this study aims to describe the

perception of stress in one’s self, romantic partner,

and community. These data will advance

understanding of stress related to COVID-19 social

restriction in Indonesia’s context. Further, the results

have the potential to inform culturally appropriate

responses to help combat the adverse effects of stress

during pandemics in Indonesia.

2 METHODS

This study used inductive thematic analysis to

examine individuals’ perceptions of their own

(individual), their romantic partner, and their

community stressors during the early phases of the

COVID-19 pandemic.

2.1 Materials

In this study, participants were asked to respond to

demographic questions and three open-ended

questions and collected data using Qualtrics online

survey. The questions were derived from Lazarus and

Folkman’s stress theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984)

that explains stress as a subjective matter. Questions

used were:

1) What stressors are you experiencing due to

COVID-19?

2) What stressors do you think your romantic

partner is experiencing due to COVID-19?

3) What stressors do you think others in the

community (e.g., friends, neighbors) are

experiencing due to COVID-19?

Participants were asked to elaborate on their

responses as much as possible.

Participants had to be 18 years and older,

currently living in Indonesia, in a romantic

relationship for more than a year, and living together.

Exclusion criteria were having a partner who filled in

the survey, completed the survey more than 15

minutes and less than 24 hours (to rule out

participants who were not taking the survey

seriously).

2.2 Participants

A total of 2,021 participants accessed the survey from

April 22 to June 29, 2020. However, 856 of them did

not meet inclusion criteria; 637 participants

completed the survey in under 15 minutes, the other

9 participants completed the survey in more than 24

hours. Sixty-seven participants did not meet the

criteria because they answered “Yes” or “Do not

know” when asked whether their partner had

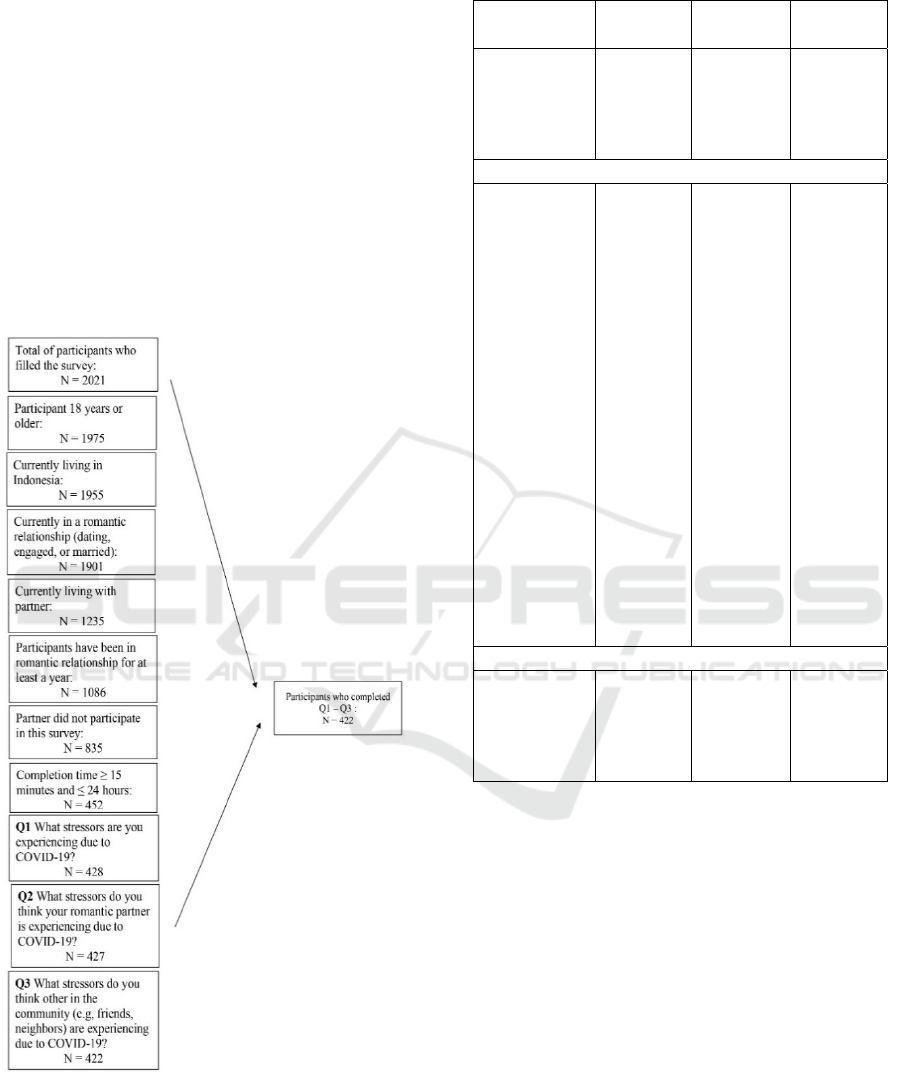

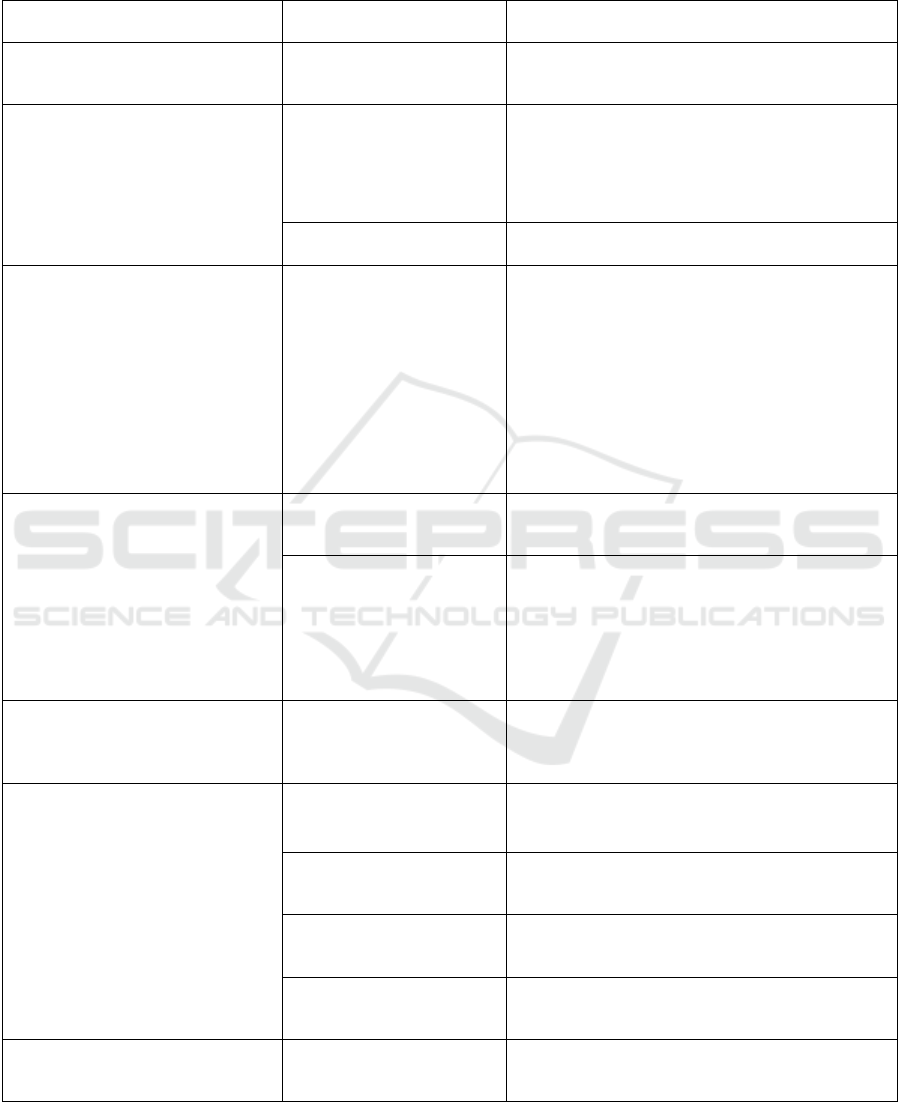

completed the survey. See Figure 1 for details

regarding data screening.

The number of participants who met the criteria in

the study was 452 participants. However, 30

participants did not complete the stress column for

individuals, perceived partners, and communities.

Thus, the final participants’ answer analyzed was 422

participants ranging in age 19 to 65 years old

(M=31.49, SD=7.43). Detailed information about

participant’s demographics can be seen in Table 1.

2.3 Procedures

This study was a part of a larger registered global

project examining COVID-19 stress and well-being

(https://osf.io/s7j52). Institutional review board

approval was obtained from Arizona State University

review board (IRB ID: STUDY00011717) and

supported by BINUS University’s board of ethics

(No: 021/VR.RTT/III/2020).

Eligible participants were directed to an online

survey, which contained a copy of the informed

consent and screening questions. If eligible,

participants were automatically directed to the

research survey, which took approximately 30

minutes to complete. Participants were asked to fill in

screening questions such as “Are you 18 years old or

older?”, “Do you currently live in Indonesia?”. The

questions were aimed to determine age, residence

place, romantic relationship, and how long they have

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

405

been in a romantic relationship. Participants’ answers

will be filtered again according to inclusion criteria,

as described in Picture 1.

Eligible participants were asked to fill in

demographic questions such as age, gender, religion,

area of employment, and yearly income. Examples of

demographic questions are “How old are you?”,

“What is your gender identity”. Participants

responded to additional COVID-19 questions,

individual and relational well-being questions, and

coping responses following these questions. All

questions were presented in Bahasa Indonesia. This

survey is part of a more extensive study, wherein

results were prepared across nations (see Chiarolanza

et al., under review).

Figure 1: Participant screening.

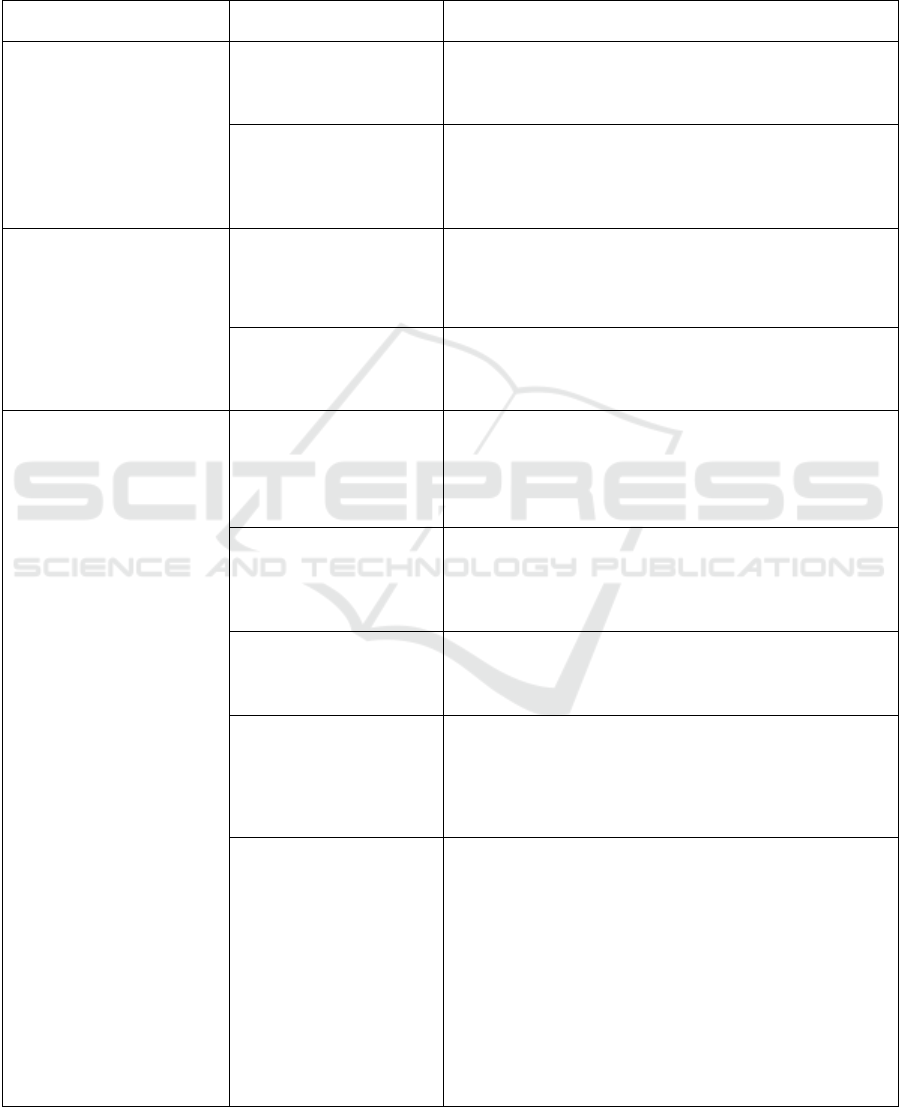

Table 1: Participant’s demographic.

Gender Male

N (%)

Female

N (%)

Total

N (%)

Male

Female

Other

Blank

85

(20.14)

-

-

-

-

335

(79.38)

-

-

85 (20.14)

335

(79.38)

1 (0.24)

1 (0.24)

Yearly Income

IDR 0 to

49.999.999,-

IDR

50.000.000,-

to

119.999.999,-

IDR

120.000.000,-

to

249.999.999,-

IDR

250.000.000,-

to

499.999.999,-

IDR

500.000.000,-

to

999.999.999,-

IDR > 1

billion

Other/Blank

25 (5.92)

19 (4.50)

26 (6.16)

8 (1.90)

7 (1.66)

-

-

137

(32.46)

97 (22.99)

58 (13.74)

31 (7.35)

11 (2.61)

1 (0.24)

-

162

(38.39)

116

(27.49)

84 (19.90)

39 (9.24)

18 (4.27)

1 (0.24)

2 (0.47)

Child

Yes

No

Other/Blank

62

(14.69)

23 (5.45)

-

196

(46.45)

139

(32.94)

-

258

(61.14)

162

(38.39)

2 (0.47)

2.4 Data Analysis

Data from participants’ responses to the three open-

ended questions were analyzed using inductive

thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Researchers followed the six-phase procedure of

inductive thematic analysis as suggested by Braun

and Clarke (2006): 1) data familiarization by reading

and re-reading; 2) initial code generation; 3)

searching for themes; 4) theme review; 5) defining

and naming themes; and 6) translation of theme map.

The first, second, and third authors fluent in Bahasa

Indonesia analyzed Indonesia’s data set, presented

here.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

406

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Self-report data from 422 participants in Indonesia

reflect the complexity and uniqueness of stressors

related to the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our findings showed ten overarching themes,

eight of which were identical in individual, perceived

partner, and community stressors, whereas two others

only occur in individual and perceived partner’s

stressor. Eight themes reflected the perception of the

individual, partner, and community stressors were 1)

health-related concerns; 2) financial concerns; 3)

challenges and changes in managing personal life,

work, and study; 4) uncertain future; 5) limited

freedom, 6) stress from others, 7) neutral/positive

impact, and 8) emotional discomforts. Two other

themes, “Physical symptoms” and “Mal-adaptive

dynamic in the couple relationship” did not emerge in

the participant’s perception of community stressors.

3.1 Health-related Concerns

The first theme was associated with health-related

concerns. Participants reported being worried about

themselves and their family’s health. The health

concerns were not only related to COVID-19 but also

general health exacerbated by the pandemic and

related government policy. Participants (N= 63)

reported health-related concerns, such as being

worried they could get infected. This fear of infection

was also applied to their family being infected

because they still have to work outside the home.

“I am WFH, and my partner is still working. It makes

us worried about the possibility of him getting

infected because he is active outside.” -[woman, 28

years old, area of employment: education]

Participants also perceived their partner's

experiencing fear of getting infected because some

society members still consider COVID-19 as not

harmful and prefer not to obey health protocols (such

as social distance, masks).

“Lack of awareness of outsiders (other people) about

social distancing and maintaining health,

cleanliness” - [woman, 32, area of employment:

education]

Aside from COVID-19 related health concerns,

participants also reported that they were worried

related to general health. Concerns about general

health happened when they were caretakers of

parents/children with chronic illness. Due to large-

scale social restrictions, in late March-April 2021,

some hospitals in Indonesia were limiting their

services (Tempo, 2020). Moreover, there was a surge

in the price of health appliances (mask, hand

sanitizer), thus making it difficult to protect one’s

health. Concerns related to access to health

appliances were also reported from the perceived

community perspective.

"Soaring prices for masks and sanitizers, as

well as the availability of goods that often run out"

- [woman, 31, area of employment: business]

Participants also observed that their community

(i.e., neighbors) was worried about unclear media

coverage about dealing with the virus.

3.2 Financial Concerns

The second theme was associated with financial

concerns. Participants (N=30) reported facing

financial problems such as overdue unpaid

installments while having no income. This financial

concern was somehow related to their health

concerns. The increase in the price of medical devices

and the difficulty in getting health services are

perceived as stress by the participants. Moreover,

many of the participants still had to go to work, which

caused them to be concerned about bringing the virus

home.

“There is no income because of cutting off from work,

or you could say that laid off because of this epidemic

!!!!! “ -[woman, 23 years old, area of employment

information not available]

Participants also perceived their partner to be

experiencing financial stressors, such as being laid

off, difficulties finding work, and having no income.

“The office is closed, so s/he must be laid off” -[man,

34 years old, area of employment: business]

Similarly, participants also perceived financial

stressors in their community, such as losing a job,

having no income, and unable to pay installments.

"Stress about income and think about mortgage

payments" -[woman, 40 years old, area of

employment: business]

3.3 Challenges and Changes in

Managing Personal Life, Work,

and Study

The third theme was “challenges and changes in

managing personal life, work, and study”. This

participant’s (N=50) concern is perceived as one’s

own, partner’s, and community’s stressors. As a

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

407

means to control virus spread, the Government

strongly suggested staying at home. During the first

months of the pandemic (March 2020), individuals

were asked to work and carry out activities at home.

This condition led to increased household load

and workload, which was likely associated with the

inability to manage the demanding roles. Increasing

household work could occur because, within large-

scale social boundaries, work and personal life

(household, child care/education) occur

simultaneously.

“Working at home is very difficult to manage time, in

the sense that working hours can extend into the

night.” -[man, 44 years old, area of employment:

education]

Participants also reported technology-related (i.e.,

internet) stressors experienced by partners.

“The internet is often down, which interferes with

work from home” -[man, 42 years old, area of

employment: education]

Similarly, participants perceived that their

community also found it challenging to adapt to

changes in their work routines and working hours.

“Difficulty adapting to work at home patterns.

Working hours may be longer. Dependence on the

internet network” -[man, 44 years old, area of

employment: education]

Most participants experienced difficulties and

remote working challenges, especially since working

at home was not common in Indonesia. Therefore, it

was uncommon to have a home office/dedicated

space to work. Moreover, the challenges in working

remotely also happen because they were lacking in

gadgets or experiencing poor internet connection.

Additionally, the new work-from-home orders

were also a challenge for couples, especially those

who were dual-earners. While both partners were

required to work, the domestic tasks are still

considered the wives/female’s tasks. Traditional

gender role explains why some husbands expressed

their concerns for wife’s stress (increased domestic

and work burden).

3.4 Uncertain Future

Feelings of uncertainty are felt in several areas of life,

such as future, work, study plans. Participants (N=12)

were unsure about travel and even wedding plans due

to large-scale social restrictions. The prominent

feeling of uncertainty was understandable, given that

no one knows when the pandemic will be over; even

the Government cannot guarantee when the large-

scale social restriction will be over. Most participants

also reported feelings of uncertainty related to travel

and wedding planning due to large-scale social

restrictions.

“The uncertainty will end the COVID-19 outbreak” -

[man, 33 years old, area of employment: Science and

Technology]

Participants also perceived that their partners

experienced stress related to uncertainty about their

future plans.

“Uncertainty in the continuation of the study” -

[woman, 26 years old, area of employment: Health

Care and Medicine]

Similar concerns were perceived in their

community, mainly as they related to future planning.

“Friend’s marriage without a reception (even

backward because the marriage fee is used to

survive)” -[woman, 25 years old, area of

employment: Law Enforcement and Armed Forces]

According to the Indonesian culture, weddings are

generally celebrated with a grand ceremony by

inviting many relatives and entire families to share

happiness by serving or offering food and drinks,

dancing, and singing songs together (Riyani, 2019).

Thus, it is understandable that uncertainty in the

future, such as an uncertain wedding date, can be a

stressor for the individual in a romantic relationship

during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.5 Limited Freedom

Participants (N=36) reported a loss of personal

freedom for social, cultural, and spiritual activities as

a stressor. Due to the Government’s regulation,

participants needed to stay at home. When some of

the participants were still working from the office, it

is difficult for them to commute because less public

transportation was available. Moreover, participants

reported that they were not able to conduct social

activities. They also were unable to do leisure

activities/vacations outside the home, resulting in

boredom. Moreover, the Government’s tradition of

Mudik (back to hometown) and Eid prayers at the

Mosque is prohibited. “You have to stay at home

because you are usually busy outside the house. Spin

your brain so you can continue to be creative.” -

[man, 23 years old, area of employment: Arts and

Entertainment]

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

408

Participants also perceived that their partner

experienced limited personal freedom as a stressor.

This limitation in mobility hinders some of the

participants from socializing with their neighbors or

family.

“Difficulty in getting along with family, neighbors

and other close relatives” -[man, 30 years old, area

of employment: education]

Participants also perceived that their community

experienced limited personal (i.e., unable to leave the

house freely without fear), social (i.e., unable to visit

family), spiritual (i.e., unable to go to

Mosque/Church), and cultural freedom (i.e., unable to

do ‘Mudik’).

“I want to gather, I want to worship, I want to go out,

and I hear about those complaints” -[woman, 29

years old, area of employment: education]

3.6 Stress from Others

Participants (N=25) felt they were responsible for

providing for their family’s needs but were also afraid

of spreading the virus to their families.

“Trying to please a partner who is less comfortable

at home” -[woman, 32 years old, area of

employment: education]

Moreover, participants perceived that their

partner felt pressured by the dishonesty of

government work and felt controlled by the

Government.

“Government strategy/response to outbreak

management that is considered slow / lacking

transparency” -[man, 44 years old, area of

employment: education]

Moreover, participants also reported domestic

violence as a form of stressor in their community.

Aside from stressors caused directly by another

person (i.e., violence), indirect stressors also occurred

in the form of fear of being infected because some

society members failed to follow health protocol (i.e.,

wearing a mask, physical distancing).

“Environmental safety is actually reduced.”-

[woman, 34 years old, area of employment: business]

3.7 Neutral or Positive Impact

Interestingly, despite the stressors associated with

COVID-19, some participants (N=7) reported not

experiencing stress or negative feelings. Moreover,

some of them even reported positive impacts, such as

more time to spend with family.

“There were almost no stressors during this

pandemic because working from home made

everyone gather at home and do activities that were

rarely done before” -[woman, 34 years old, area

of employment: education]

Some participants also perceived that their

partners did not experience stress. They even express

their gratitude to God because their family can

survive in times of COVID-19.

“Alhamdulillah [“praise be to God’], you can say

that we are still on the threshold of being stable to

support our little family.”-[woman, 23 years old]

Similarly, some participants also perceived that

no stress happens in their community.

“Nothing” -[woman, 28 years old, area of

employment: business]

3.8 Emotional Discomforts

Participants (N=19) experienced various unpleasant

emotions such as anxiety/worries, stress, and fear.

One of the triggers of this emotion was news related

to COVID-19 (i.e., increasing people infected).

“News related to the development of Covid,

especially related to the symptoms of Covid sufferers.

So that if there are slight symptoms (such as

coughing) to worry” -[woman, 29 years old, area of

employment: Science and Technology]

Participants also perceived that their partner

experienced emotional tension such as feeling more

paranoid and one of the triggers was news related to

COVID-19.

“Psychic only, more alert and paranoid” -[woman,

27 years old, area of employment: Health Care and

Medicine]

Moreover, psychological stressors, such as panic,

boredom, and anxiety, were also reported as

perceived community stressors.

“Actually, more of a psychological stressor, such as

panic, boredom. Nevertheless, for work, as far as I

know, most can still work from home. Some friends

who are young and live with their parents also seem

uncomfortable at home” -[woman, 32 years old, area

of employment: education]

Lastly, many participants expressed their anxiety

because of the news in the media, and many of them

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

409

had difficulty trusting the Government of Indonesia’s

capital (Jakarta).

3.9 Physical Discomfort

Physical discomfort was perceived as an individual

and relational stressor; the theme only emerged for

perceptions of COVID-19 stress for self and partner.

Specifically, participants (N=6) reported

experiencing somatic complaints (e.g., fatigue). They

also felt worried whenever they experience physical

symptoms similar to COVID-19 symptoms, such as

coughing.

“Very tired because office work has become

increasingly difficult due to WFH.” -[woman, 32

years old, area of employment: education]

Participants also perceived their partner to

experience physical symptoms such as fatigue due to

uncertain working hours during ’working from home’

(WFH).

“Fatigue due to work from home that has no clear

limit to work” -[man, 28 years old, area of

employment: business]

Based on frequency, responses about physical

discomfort symptoms were relatively few compared

to other themes (i.e., four responses in this theme,

compared to 63 responses in health-related concerns

theme).

3.10 Maladaptive Dynamic in The

Couple Relationship

Lastly, participants (N=10) perceived maladaptive

dynamics in their relationship as a stressor. Couples

who lived together tend to developed maladaptive

dynamics, which can lower relationship quality and

personal well-being, such as conflict related to

financial and less sexual activity.

“Feeling cooped up at home. There were several

conflicts with partners because they were triggered

by feeling depressed at home. Have to work at home

while taking care of the house too” -[woman, 35

years old, area of employment: business]

Participants also perceived that their partner felt

that their sexual activity was being disturbed, and

relational conflict increased.

“Lack of freedom in sexual activity” -[woman, 23

years old, area of employment: Science and

Technology]

3.11 Discussion

Qualitative results based on 422 individuals living in

Indonesia during the early phase of the COVID-19

pandemic reflected common themes for how

individuals perceive stressors related to COVID-19

effects on their own, partners, and community. The

overlapping themes in individuals and partners may

result from partners’ shared experiences

(Bodenmann, Randall, & Falconier, 2016). Previous

research found that the experience of stress was not

only caused by one’s stress but also the couple-level

stress process (Wickrama, O’Neal, & Klopack,

2020).

This study found that the health and financial

stressors were prominent. Health-related concerns

were found in the majority of participants’ answers.

It is understandable due to the health-related nature of

the pandemic and as a consequence of social

restriction. Moreover, surge price in health aids (such

as masks) at the beginning of the pandemic likely

occurred due to the increase in demand, and shortage,

of these supplies. Indeed, some individuals were

hoarding these materials, a phenomenon that was not

unique to Indonesia (Wang & Hao, 2020).

The theme related to “challenges and changes in

managing personal life, work and education” revealed

the inevitable changes in the work organization and

academic world, accompanied by economic concerns

and financial troubles. Recent research on family

functioning in Italy has shown that the pandemic has

increased parenting stress, causing strains and a

higher risk for family health (Spinelli, Lionetti, Setti,

& Fasolo, 2020). Moreover, rapid changes in work

and family roles during the pandemic also lead to

more work-family conflict and less work-family

enrichment, especially for individuals who were

struggling pre-pandemic individuals (e.g., Vaziri,

Casper, Wayne, & Matthews, 2020)

The overlapping financial concerns perceived in

one’s self, partner, and community showed the scope

of economic problems in Indonesia. Like health-

related concerns, financial concerns can be

considered stress outside the relationship (Randall &

Bodenmann, 2017). However, if the external stress is

not dealt with properly, it can spill over into the

relationship, increase the possibility of conflict, and

reduce relationship quality (Barton, Beach, Bryant,

Lavner, & Brody, 2018).

Other themes were related to limited freedom and

an uncertain future. Aside from personal and social

freedom, data showed that participants in Indonesia

perceived limitations in spiritual/religious habits (i.e.,

unable to go to Mosque/Church) and cultural freedom

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

410

(i.e., unable to do ‘mudik’ tradition). The data

collection time (22 April-29 June) co-occur with the

time of the fasting month (a religious ritual for

Muslims, the religion of the majority of Indonesians).

Fasting is carried out from April, 24 to May, 23, and

reaches the peak celebration on May 24-25, Eid al-

Fitr. In the fasting month and Eid al-Fitr, most

Indonesian practice the traditions of breaking the fast

together, returning home (‘Mudik’), and gathering

with the extended family.

‘Mudik’ is similar to homecoming/return to the

family tradition of Thanksgiving/Christmas/Chinese

New Year. However, there are some differences

(Yulianto, 2019): 1) although annual Mudik is done

in Eid al Firth/Lebaran season (Muslim celebration),

non-Muslim are also fully engaged with this tradition.

Indonesian people have a tradition to ask for

forgiveness (not only in Muslim); 2) There is an

exodus before and after the homecoming. People

from urban areas travel to their home towns/villages

using public or private transportation. After the

celebration is over, they move back to urban areas,

and some of them even bring their relatives to work

with them in urban areas. Thus, the Government

restricts ‘Mudik’ to avoid virus spread, which was a

stressor for both Muslims and non-Muslim in

Indonesia because social gatherings were an essential

part of Indonesian culture, which was reflected in our

collectivistic culture (Hofstede, 2011).

Understanding Indonesia as a collectivistic

culture can also explain the stressors perceived to

impact others. Indonesia has a high collectivism

cultural dimension, in which people are bone into

extended families which protect them in exchange for

loyalty (Hofstede, 2011). As a consequence, a person

could feel responsible for his parents and extended

family. In a challenging situation such as the COVID-

19 pandemic, this responsibility can be perceived as

a stressor.

Another theme that occurred was “maladaptive

dynamic in couple relationship”. This dynamic, such

as conflict or lower sexual interaction, happened for

several possible reasons. First, participants felt

cooped up at home, where they also live with

parents/in-laws; thus, their sexual activity was likely

affected. Second, if one partner felt depressed (or

other distress) because of reasons external to their

relationship, prior research has shown this stress

could spill over into the relationship, affecting their

partner and resulting in lower marital quality

(Randall & Bodenmann, 2017).

Participant’s response in the” maladaptive

dynamic in couple relationship” theme was not as

much as other themes (i.e., health and financial

concerns). However, it was still worthy to note, given

its impact on marital quality. The relatively small

number of responses about couple dynamics maybe

because it was considered private information. In

Indonesia, where most people have Muslim religion,

it is suggested not to bring up private “disgrace”

publicly.

Interestingly, some participants reported a neutral

or positive response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Compare to other themes, positive responses to

COVID-19 were relatively low (only five responses).

While small, these results imply resilience and

resources in challenging times. One possible resource

is a belief in God. A recent survey found that most

Indonesian (96%) agree that belief in God is

necessary to be moral and have good values (Tamir,

Connaughton, & Salazar, 2020). In line with (Lazarus

& Folkman, 1984) stress theory, not all individuals

perceived stress despite the global pandemic. There

were a small number of people who reported no

stress, even positive impact. They might have enough

resources to cope with challenges, so they did not

perceive COVID-19 related challenges as stressors.

Moreover, this study also showed that perception

of stress and the couple dynamic as a response of

stress in an individual within the romantic

relationship was influence by cultural context

(Bodenmann, 1995; Ogolsky, Rice, Theisen, &

Maniotes, 2017). Thus, coping strategies need to

consider the cultural context, such as local norms and

collectivistic cultural values. Given the importance of

belief in God, then “Reaching Up” or strategies

accessing spiritual, religious, and ethical values (i.e.,

daily devotions or prayer) might be practical to deal

with COVID-19 related stressors (Fraenkel & Cho,

2020). Similarly, given the high collectivistic cultural

value, “Reaching Around” or strategies utilizing

social support (i.e., video conference birthday

celebration to replace face to face meetings, sending

care packages to family or friends to show support

and foster connection) can be valuable for individuals

in a romantic relationship living in Indonesia.

Despite its strengths, this study has several

limitations that should be noted. First, participants in

this study were individuals in romantic relationships;

however, data were collected from one partner (i.e.,

not dyadic). Lastly, this study captured experiences in

the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic and

cannot be generalized/extrapolated to a later time or

current conditions (i.e., more than a year after

COVID-19 is considered a pandemic).

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

411

4 CONCLUSIONS

Not surprisingly, individuals in Indonesia during the

early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic reported

subjective stress. The inductive thematic analysis

showed ten overarching themes that described an

individual’s own, partner’s, and community’s

stressors. Despite the limitations, results from this

study shed light on individuals’ perceptions of stress

during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Further research can use the ten identified themes

to create a self-report assessment designed to evaluate

stressors in the face of global pandemics. This

instrument can be used both for research and

screening tools, informing further culturally

appropriate stress management intervention in the

pandemic. Further research is encouraged to analyze

perceived stressors related to COVID-19 across

dyadic and cross-cultural factors, such as gender role

and individualism-collectivism cultural values.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ER and SF are currently final year undergraduate

students of Psychology at Bina Nusantara University.

PCBR is a lecturer at Bina Nusantara University, AG

is a lecturer in Universitas Indonesia, and CC is an

Assistant Professor at the Department of Dynamic

and Clinical Psychology and Health Studies,

Sapienza University of Rome. AKR is an Associate

Professor from Arizona State University. All authors

discussed the findings thoroughly, read, and approved

the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Badan Pusat Statistik. (2020). Tingkat Pengangguran

Terbuka (TPT) sebesar 7,07 persen. Retrieved May 31,

2021, from https://www.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2020/

11/05/1673/agustus-2020--tingkat-pengangguran-terbu

ka--tpt--sebesar-7-07-persen.html

Barton, A. W., Beach, S. R. H., Bryant, C. M., Lavner, J.

A., & Brody, G. H. (2018). Stress spillover, African

Americans’ couple and health outcomes, and the stress-

buffering effect of family-centered prevention. Journal

of Family Psychology, 32(2), 186–196. https://doi.

org/10.1037/fam0000376

Bodenmann, G. (1995). A systemic-transactional

conceptualization of stress and coping in couples. Swiss

Journal of Psychology, 54(1), 34–49.

Bodenmann, G., Randall, A. K., & Falconier, M. K. (2016).

Coping in Couples: The Systemic Transactional Model

(STM). In G Bodenmann, A. K. Randall, & M. K.

Falconier (Eds.), Couples Coping with Stress: A Cross-

Cultural Perspective. New York: Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15877-8

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in

psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2),

77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2010).

Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-

lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive

symptomatology in the chicago health, aging, and

social relations study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2),

453–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017216

Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., &

Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and

interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science,

10(2),238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570

616

Chiarolanza, C., Sallay, V., Joo, S., Gaines, S., Rumondor,

P. C., Otermans, P., … Murphy, E. (n.d.). Perspectives

of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community

stressors in the face of the COVID-19 Pandemic - A

qualitative Study across 20-Nations. Frontiers in

Psychology.

Daube, C. H. (2021). Covid-19 third Wave - Impact on

financial markets and economy. Kiel, Hamburg: ZBW

- Leibniz Information Centre for Economics.

Ensel, W. M., & Lin, N. (1991). The life stress paradigm

and psychological distress. Journal of Health and

Social Behavior, 32(4), 321–341.

Flesia, L., Monaro, M., Mazza, C., Fietta, V., Colicino, E.,

Segatto, B., & Roma, P. (2020). Predicting perceived

stress related to the Covid-19 outbreak through stable

psychological traits and machine learning models.

Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(10), 3350. https://

doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103350

Fraenkel, P., & Cho, W. L. (2020). Reaching up, down, in,

and around: Couple and family coping during the

Coronavirus Pandemic. Family Process, 59(3), 847–

864. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12570

Friedler, B., Craser, J., & McCullough, L. (2015). One is

the deadliest number: The Detrimental effects of social

isolation on cerebrovascular diseases and cognition.

Acta Neuropathol, 129(4), 493–509. https://doi.org/

doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1377-9

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The

Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in

Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/1

0.9707/2307-0919.1014

Jacubowski, A., Abeln, V., Vogt, T., Yi, B., Choukèr, A.,

Fomina, E., … Schneider, S. (2015). The impact of

long-term confinement and exercise on central and

peripheral stress markers. Physiology & Behavior,

152(Pt A), 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.p

hysbeh.2015.09.017

Karademas, E. C., & Roussi, P. (2017). Financial strain,

dyadic coping, relationship satisfaction, and

psychological distress: A dyadic mediation study in

Greek couples. Stress and Health, 33(5), 508–517.

https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2735

Kompas TV. (2021). Selama pandemi, angka perceraian

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

412

meningkat.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and

coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Ogolsky, B. G., Rice, T. M., Theisen, J. C., & Maniotes, C.

R. (2017). Relationship maintenance: A review of

research on romantic relationships. Journal of Family

Theory and Review, 275–306. https://doi.org/10.

1111/jftr.12205

Pagel, J. I., & Choukèr, A. (2016). Effects of isolation and

confinement on humans-implications for manned space

explorations. Journal of Applied Physiology, 120(12),

1449–1457. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00928.

2015

Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A., Menaghan, E. G., &

Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of

Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 337–356.

Permana, F. E. (2020). Banyak Orang Bercerai Saat

Pandemi Covid-19.

Pietrabissa, G., & Simpson, S. G. (2020). Psychological

consequences of social isolation during COVID-19

outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(September), 9–

12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02201

Prihatin, I. U. (2020). Kemenag sebut angka perceraian

mencapai 306.688 Per Agustus 2020. Retrieved May

30, 2021, from https://www.merdeka.com/peristiwa/

kemenag-sebut-angka-perceraian-mencapai-306688-pe

r-agustus-2020.html

Randall, A. K., & Bodenmann, G. (2017). Stress and its

associations with relationship satisfaction. Current

Opinion in Psychology, 13, 96–106. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.010

Riyani, I. (2019). Performing Islamic Rituals in Non-

Muslim Countries: Wedding ceremony among

Indonesian Muslims in The Netherlands. Journal of

Asian Social Science Research, 1(1), 47–61. https://doi.

org/10.15575/jassr.v1i1.7

Satuan Tugas Penanganan COVID-19. (2020). Data

sebaran. Retrieved June 2, 2021, from https://

covid19.go.id/

Savage, M. (2020). Mengapa angka perceraian di berbagai

negara melonjak saat pandemi Covid-19? Retrieved

May 30, 2021, from BBC Worklife website:

https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/vert-cap-55284729

Spinelli, M., Lionetti, F., Setti, A., & Fasolo, M. (2020).

Parenting stress during the COVID-19 outbreak:

Socioeconomic and environmental risk factors and

implications for children emotion regulation. Family

Process,x(x),1–15.https://doi.org/10.1111/famp .12601

Tamir, C., Connaughton, A., & Salazar, A. M. (2020). The

Global God Divide. Retrieved May 31, 2021, from Pew

Research Center website: https://www.pewresearch.

org/global/2020/07/20/the-global-god-divide/

Tempo(2020). Rumah Sakit Batasi Layanan Pasien.

Retrieved June 12, 2021, from https://koran.tempo.co/r

ead/nasional/452204/rumah-sakit-batasi-layanan-pasien

Vaziri, H., Casper, W. J., Wayne, J. H., & Matthews, R. A.

(2020). Changes to the work-family interface during the

COVID-19 pandemic: Examining predictors and

implications using latent transition analysis. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 105

(10), 1073–1087. https://doi.o

rg/10.1037/apl0000819

Wa-Mbaleka, S., & Costa, A. P. (2020). Qualitative

research in the time of a disaster like covid-19. Revista

Lusofona de Educacao, 48(48), 11–26. https://doi.org/

10.24140/issn.1645-7250.rle48.01

Wang, H. H., & Hao, N. (2020). Panic buying? Food

hoarding during the pandemic period with city

lockdown. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 19(12),

2916–2925. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/

S2095-3119(20)63448-7

WHO. (2020). WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

dashboard. Retrieved June 2, 2021, from https://co

vid19.who.int/

WHO Indonesia. (2021). Coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) Situation Report - 67. Retrieved June 2,

2021, from https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-sour

ce/searo/indonesia/covid19/external-situation-report-6

7.pdf?sfvrsn=3a1e8ba4_3/

Wickrama, K. A. S., O’Neal, C. W., & Klopack, E. T.

(2020). Couple-level stress proliferation and husbands’

and wives’ distress during the life course. Journal of

Marriage and Family, 82(3), 1041–1055. https://doi.

org/10.1111/jomf.12644

Wikanto, A. (2020). Daftar zona merah corona di Indonesia

per 23/12/2020, Jawa Tengah berkurang. Retrieved

May 31, 2021, from https://kesehatan.kontan.co.id/n

ews/daftar-zona-merah-corona-di-indonesia-per-23122

020-jawa-tengah-berkurang?page=all

Yulianto, V. I. (2019). Is the Past Another Country? A Case

Study of Rural Urban Affinity on Mudik Lebaran in

Central Java. Journal of Indonesian Social Sciences

and Humanities, 4(01), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.14203

/jissh.v4i0.118

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

413

APPENDIX

Perceived Individual Stressor

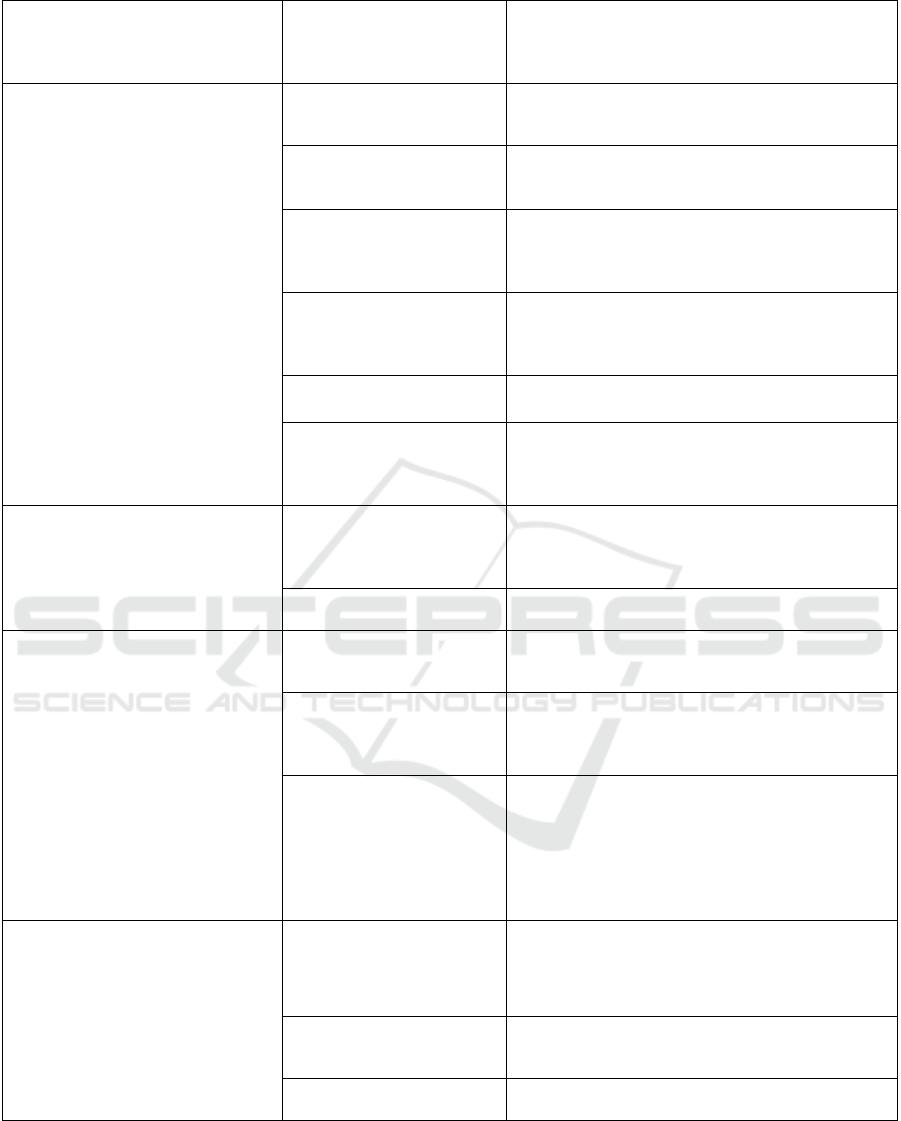

Table 2: Themes, sub-theme, and answer example for individual, stressor.

Theme Sub-theme Answer Example

Maladaptive dynamic in

couple relationship

Interrupted activities with

partner

"Inability to travel freely. Currently my partner and I live in

the house of my partner's parents, so our sexual activity is

ex

p

eriencin

g

obstacles and even no activit

y

at all."

Conflict and boredom

with partner and family

"Feeling cooped up at home. There were several conflicts

with partners because they were triggered by feeling

depressed at home. Have to work at home while taking care

o

f

the house too"

Physical discomfort

symptoms

Physical discomfort

symptoms

"Very tired because office work has become increasingly

difficult due to WFH"

"Hard to slee

p

"

Psychosomatic

"News related to the development of Covid, especially related

to the symptoms of Covid sufferers. So that if there are a few

sy

m

p

toms

(

such as cou

g

h

)

to be worried"

Personal freedom for social,

cultural and spiritual

activities is limited

Disrupted social life

"I work from home but I can't interact with other people, I

can't go back to my hometown and can't meet old people in

the village"

"Can't han

g

out with

f

riends and meet new

p

eo

p

le"

Loss of personal freedom

(Kehilangan kebebasan

personal)

"Lack of entertainment at home. For me outside the home is

a thing to entertain myself"

"You have to sta

y

at home,

y

ou can't do activities outside"

Loosing spiritual and

cultural routines

"Can't go to the mosque"

"Can't go anywhere, can't go home"

Boredom resulting from

staying at home

"You have to stay at home, because you are usually busy

outside the house. Spin your brain so you can continue to be

creative"

"Bored because (I/we) can not travel"

Difficulties and worries

going to public places

"It is difficult to get public transportation when you have to go

to the office. Like at the beginning of the PSBB (large scale

social restriction), the unclear KRL (Electril Rail Train)

information, I left the office and arrived at the TJ. Barat

station at 5 o'clock, the security guard informed me that the

latest train had passed and I walked looking for no public

transportation, until finally I cried on the side of the road and

asked my husband to pick you up to the ANTAM area because

I

had to walk (no motorcycle taxis, busways and public

transportation)"

"Alwa

y

s cautious

(p

aranoid

)

when leavin

g

the house"

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

414

Emotional well-being

Anxiety about news

related to COVID-19

"The news is very dark and negative makes panic."

"News related to the development of Covid, especially related

to the symptoms of Covid sufferers. So that if there are slight

s

ymptoms (such as coughing) to worry"

Emotional tension

"Anxious"

"Stress"

"Afraid"

Perceived neutral and

positive impact of COVID-

19

No stress and more time to

spend with family

"There were almost no stressors during this pandemic

because working from home actually made everyone gather

at home and do activities that were rarely done before"

Uncertainties and obstacles

for future plans

Uncertainty about the

future, jobs, study plans,

and the sustainability of

the outbreak

"The uncertainty will end the covid-19 outbreak"

"Initial stress due to uncertainty in handling and running

business"

Future

p

lans disru

p

ted "Must cancel vacation

p

lans with

p

artner"

Challenges and changes in

managing personal life,

work and study

Increased domestic and

work burden

"Provide food for the whole family from waking up untill

nite"

"Since there was the COVID-19 outbreak, I feel much more

pressure because I currently have 2 children under five and

this outbreak my husband was forced to be at home (not

working) which required me to work extra (household)

because besides having to take care children, must also serve

the husband."

Job Loss "Job loss"

Difficulty in doing work

and continuing study

"Work because my job is freelance, many projects are not

finished and are delayed"

"Unable to do the thesis in the lab on time (for reasons of

PSBB and so on

)

"

Difficulty in dividing time

between work and

p

ersonal life

"Working at home is very difficult to manage time, in the

sense that working hours can extend into the night."

Changes in personal and

work/educational routines

"The working hours when working from home are often more

than 8 hours, compared to when working from the office.

Often do not follow the 8.00-17.00 rule"

"The e-learning model that is currently being worked on also

has many challenges, I have to be a dynamic teacher and

read

y

to learn new thin

g

s."

Strains due to

work/business

"I can't do my business activities, because I work in a

developer, so construction has stopped and property sales

have been temporarily halted"

"There is pressure, a lot of work is done from home. But I did

well. Because I realize this is happening beyond our control"

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

415

Strain related to

education, parenting, and

child development

"Worried that children do not get enough stimulus / education

because even though we are at home but busy with work, it

seems that there is an increase in the duration of playing

gadgets because we cannot continue to play with them (the

only child who likes to play in groups)"

"Guidin

g

children to school

f

rom home"

Financial strains due to

decreasing income

Anxious about economic

condition

"Price increases and shortages of goods"

"There is no income because of cut off from work or you

could sa

y

that laid o

ff

because o

f

this e

p

idemic !!!!! "

Difficulties in surviving

due to financial

p

roblems

"Terminated from work. It is difficult to meet the necessities

o

f

li

f

e because there is no income"

Health related concerns,

both for self and family

Worried about self one's

and family's health

"Keeping the family healthy, stay at home but try to keep the

children from losing their freedom. There are still some parts

of the house that need to be repaired before moving

(currently they are still under contract) but are worried

because this situation will certainly affect the husband's job

as the only breadwinner in the house. family and family

economy."

"I am WFH and my partner is still working. This makes us

worried about the possibility of him getting infected because

he is active outside."

Lack of public awareness

in adhering to health

p

rotocols

Lack of awareness of outsiders (other people) about social

distancing and maintaining health, cleanliness

Lack of access to health

service, both general and

specific for COVID-19

rising prices for masks and vitamins,

fear and confusion to the rs when the child is sick or for

vaccination

Stress from others (family,

society, goverment)

Responsibility toward

others: Family and society

"Trying to please a partner who is less comfortable at

home"

"Fear of being a virus carrier for your family or partner at

home"

Difficulties from inner

circle

"Confused about how to convince parents and in-laws that

we can't often visit them because we are in the red zone city,

while in-laws are in the village and think we are insecure or

over reactin

g

"

Strains due to

Government’s working

methods and regulations

"Uncertainty, the government's dishonesty about the data"

"All lifestyles seem to be controlled by the government"

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

416

Perceived Partner Stressor

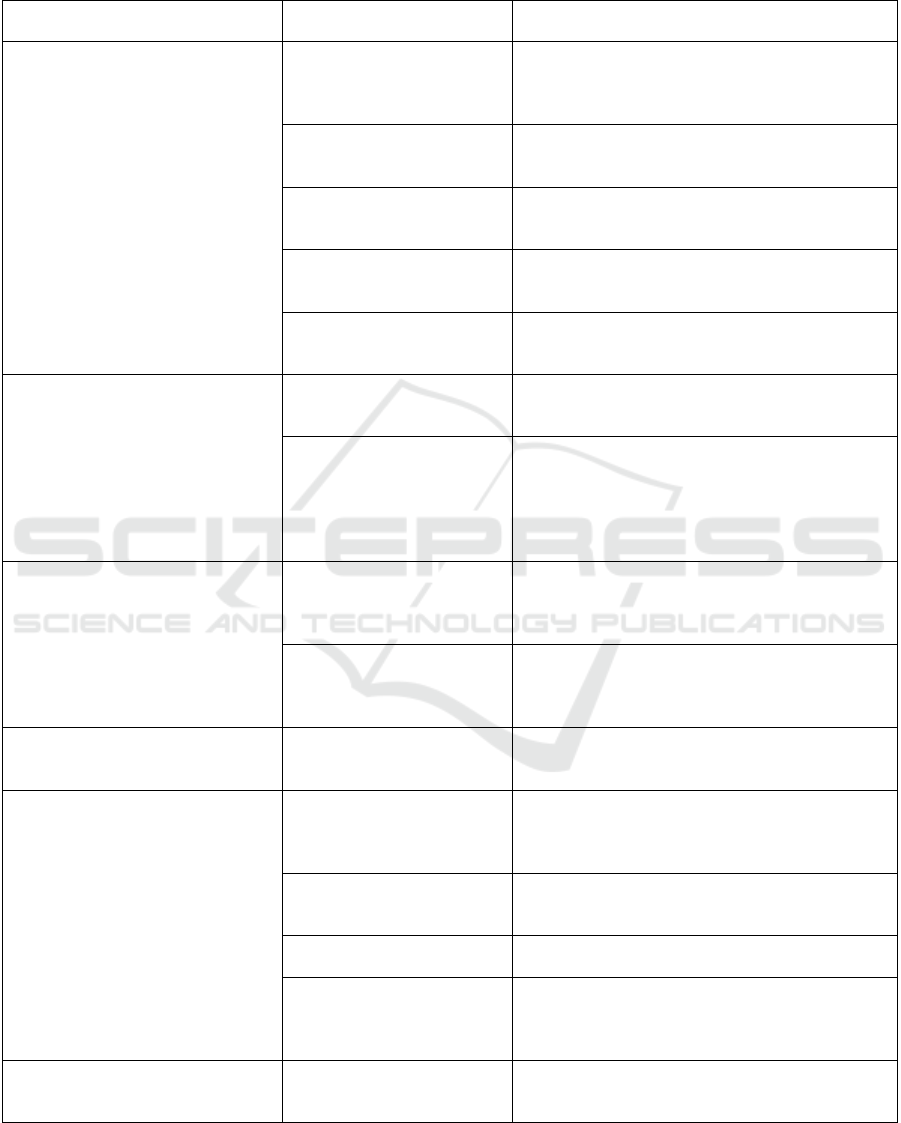

Table 3: Themes, sub-theme and answer example for partner’s, stressor.

Theme Sub-theme Answer Exam

p

le

Physical discomfort symptoms

Physical discomfort

symptoms

"fatigue due to work from home that has no clear

limit to work"

Emotional well-being

Anxiety about news related

to COVID-19

"News related to the development of Covid,

especially related to the symptoms of Covid

sufferers. So that if there are a few symptoms (such

as cough) to be worried"

Emotional tension "Psychic only, more alert and paranoid"

Similar Stres Similar Stres

"We live in apartments, where we have direct

contact with residents or other guests, such as an

elevator. All residents must use the elevator. My wife

is also pregnant, in March I was stressed because of

that, but many sources who say that babies in the

womb & toddlers have a very small risk of

contracting Covid .. However, it turned out that in

early June there was news saying that the virus had

mutated and started to infect toddlers, this is what

made me think negative again"

Maladaptive dynamic in couple

relationship

Interrupted activities with

p

artner

"Lack of freedom in sexual activity"

Conflict and boredom with

partner and family

"Because I am only at home and face children who

are also bored with home situations, I often get

angry easily because my husband also needs rest so

it is impossible for me to ask my husband for help to

accompany my child while I make orders because I

s

ell product online"

Perceived neutral and positive

impact of COVID-19

No stress and more time to

spend with family

"Alhamdulillah ["praise be to God'], you can say

that we are still on the threshold of being stable to

s

u

pp

ort our little

f

amil

y

"

Personal freedom for social,

cultural and spiritual activities is

limited

Disrupted social life

"Difficulty in getting along with family, neighbors

and other close relatives"

Loss of personal freedom

"Miss traveling (usually within 1 month there can be

3-4 tri

p

s out o

f

town or abroad

)

"

Loosing spiritual and

cultural routines

"Not free to worship"

Boredom resulting from

sta

y

in

g

at home

"Suddenly have to be at home continuously / work

f

rom home

(

because he used to

g

o to the o

ff

ice

)

"

Stress from others (family, society,

g

overment

)

Responsibility toward

others: Famil

y

and societ

y

"This fear of pandemics affects their partner's job"

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

417

Strains due to Government's

working methods and

re

g

ulations

"Government strategy / response to outbreak

management that is considered slow / lacking

trans

p

arenc

y

"

Challenges and changes in

managing personal life, work and

study

Increased domestic and work

b

urden

"Children with schoolwork, and i have to cook

ever

y

da

y

"

Difficulty in doing work and

continuing study

"The internet is often down, which interferes with

work from home"

Difficulty in dividing time

between work and personal

life

"Divide time between work and children, because of

work and home school"

Changes in personal and

work/educational routines

"WFH, which means that even though you don't go

to the office, the working hours are actually longer,

even on Saturdays, work is still being charged"

Strains due to work/business "Many companies layoff."

Strain related to education,

parenting, and child

develo

p

ment

"Pressure to take care of children (school, play)"

Uncertainties and obstacles for

future plans

Uncertainty about the future,

jobs, study plans, and the

sustainability of the outbreak

"Uncertainty in the continuation of the study"

Future

p

lans disru

p

ted "When

p

re

p

arin

g

f

or a weddin

g

"

Health related concerns, both for

self and family

Worried about self one's and

famil

y

's health

"Concerns of family members catching COVID-19"

Lack of public awareness in

adhering to health protocols

"Lack of awareness of outsiders (other people)

about social distancing and maintaining health,

cleanliness"

Lack of access to health

service, both general and

specific for COVID-19

(Minimnya akses layanan

kesehatan, baik umum

mau

p

un khusus COVID-19

)

"Difficulty obtaining drugs on the market and if they

are available they will be very expensive"

Financial strains due to decreasing

income (Tekanan finansial karena

penurunan penghasilan)

Anxious about economic

condition (Cemas terhadap

keadaan ekonomi)

"Worried because we were afraid that our savings

would run out due to no additional income other

than salary"

Difficulties in surviving due

to financial problems

"Financial condition because since the Covid-19

epidemic it has been difficult to find jobs"

Job loss "The o

ff

ice is closed so it must be laid o

ff

"

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

418

Perceived Community Stressor

Table 4: Themes, sub-theme and answer example for community, stressor.

Theme Sub-theme Answer Exam

p

le

Personal freedom for social, cultural

and spiritual activities is limited

Disrupted social life

"Because of social distancing, we rarely meet and

are a little afraid, suspicious when we meet what

else is not wearing a mask"

Loss of personal freedom

"I want to gather, I want to worship, I want to go ou

t

and I hear about those complaints"

Loosing spiritual and cultural

routines

"The habit of doing worship in a house of worship is

hindered"

Boredom resulting from

staying at home

"Inexplicability to travel causes boredom in itself"

Difficulties and worries going

to

p

ublic

p

laces

"Afraid to leave the house"

Emotional well-being

Anxiety about news related to

COVID-19

"Anxious because the news is spread excessively,

which is not necessaril

y

true"

Emotional tension

"Actually more of a psychological stressor, such as

panic, boredom. But for work, as far as I know, mos

t

can still work from home. Some friends who are

young and live with their parents also seem

uncomfortable at home"

Uncertainties and obstacles for

future plans

Uncertainty about the future,

jobs, study plans, and the

sustainabilit

y

of the outbreak

"Economic pressure of course, job and income

uncertainty"

Future plans disrupted

"Friend's marriage without a reception (even

backwards because the marriage fee is used to

s

urvive)"

Perceived neutral and positive

impact of COVID-19)

No stress and more time to

spend with family

"Nothing"

Challenges and changes in

managing personal life, work and

study

Increased domestic and work

burden

"Difficulty adapting to work at home patterns.

Working hours may be longer. Dependence on the

internet network"

Changes in personal and

work/educational routines

"Office work that knows no time"

Strains due to work/business "His business has decreased turnover"

Strain related to education,

parenting, and child

develo

p

ment

"Anxiety about family health, especially children

related to changing school patterns to distance

learnin

g

"

Financial strains due to decreasing

income

Anxious about economic

condition

"Stress about income and think about mortgage

p

a

y

ments"

Perceived Individual, Partner, and Community Stressors Related to Covid-19 Quarantine in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

419

Difficulties in surviving due

to financial problems

"Lost job / business"

Job Loss

"Trying to make money in a way that is not as

usual, housing installments that still have to be paid

amid the di

ff

icult

y

o

f

makin

g

mone

y

"

Health related concerns, both for

self and family

Worried about self one's and

famil

y

's health

"Their lack of knowledge about Covid-19, so they

are alwa

y

s consumed b

y

f

alse news"

Lack of public awareness in

adhering to health protocols

"There are still many people who go home to their

hometowns, even though my friends and neighbors

have sincerely not gone home"

Lack of access to health

service, both general and

s

p

ecific for COVID-19

"Soaring prices for masks and sanitizers, as well as

the availability of goods that often run out"

Stress from others (family, society,

goverment)

Responsibility toward others:

Famil

y

and societ

y

"Worried about being a virus carrier to people

around

y

ou"

Difficulties from inner circle

"Have to stick with old people who are verbally

abusive"

Strains due to Government’s

working methods and

regulations

"Environmental safety is actually reduced"

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

420