What Does Sejahtera Mean to You? The Interpretation of Sejahtera

based on Money-saving Habit, Happiness, and Life Satisfaction

Hasna Fauziati Zakkiyah

a

, Stella

b

, Farah Mutiasari Djalal

c

and Yosef Dedy Pradipto

d

Department of Psychology, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Prosperity, Happiness, Life Satisfaction, Money-saving Habit, Features.

Abstract: This research aims to explore the meaning of an abstract concept Sejahtera. Specifically, whether Sejahtera

was perceived differently based on people’s saving habit, level of happiness, and satisfaction with life. Feature

generation task was used to generate features that describe the meaning of Sejahtera. A total of 331

Indonesians were asked to generate features, and their level of happiness and life satisfaction were measured,

as well as their money-saving habit. The generated features were coded, counted, and classified based on

participants’ level of well-being (happiness and life satisfaction) as well as their saving habits. The

relationships among these variables were explored. The results showed that despite having some idiosyncratic

features, Sejahtera was perceived uniformly among Indonesians as ‘feeling happy’, ‘having enough’, and

‘having every need fulfilled’. These features were generated most often by participants regardless of their

level of happiness, life satisfaction, and their saving habit. These top generated features also shown a great

resemblance with the definition by Indonesian governmental regulation regarding Kesejahteraan Sosial (akin

to social welfare or literally translated as ‘prospering socially’). The results are discussed in light of theories

of concept and indigenous psychology.

1 INTRODUCTION

What comes to mind when you hear the word

Sejahtera? Hearing the word Sejahtera (akin to

‘being prosper’ in English), the word is often

associated with fulfilled economic needs. According

to a study on word association by Djalal and De

Deyne (2021; see https://smallworldofwords.org/i

d/project/visualize), the words most often associated

with the word Sejahtera are bahagia (happiness),

damai (peace, or peacefulness), sentosa (tranquil, or

a state of tranquillity), and tentram (peaceful, or to be

at peace). In accordance with previous studies, the

word Sejahtera is defined as a condition in which

someone feels prosperous, healthy, and at peace

(Widyastuti, 2021) due to perceived sufficient

managing of a variety of social problems (Suradi,

2007), including but not limited to the physical,

economical, and mental (well-being) to the extent

which all of one’s needs are fulfilled (Segel & Bruzy,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6168-8521

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4779-9329

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2767-8279

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3165-662X

in Widyastuti, 2012). This kesejahteraan sosial

(somewhat loosely translated to ‘prospering

socially’) is even regulated by the state of Indonesia;

written under the 2009 constitution of the Republic of

Indonesia number 11 article 1, kesejahteraan sosial is

a state in which a citizen has all material, spiritual,

and social needs fulfilled that they could live a decent

life oriented toward self-development, enabling them

to fulfil their social functions. In conclusion, a person

could widely be described as Sejahtera when all of

their economic needs are fulfilled.

One’s life can be considered as a prosperous

(Sejahtera) life when all the basic needs such as food,

shelter, clothing, and healthcare are fulfilled. But not

only physical needs, social needs such as harmonious

interpersonal relations, self-development, and

satisfying standard of living also play significant

contributions in determining a prosperous life

(Friedlander & Robert, 1982).

366

Zakkiyah, H., Stella, ., Djalal, F. and Pradipto, Y.

What Does Sejahtera Mean to You? The Interpretation of Sejahtera based on Money-saving Habit, Happiness, and Life Satisfaction.

DOI: 10.5220/0010752300003112

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences (ICE-HUMS 2021), pages 366-373

ISBN: 978-989-758-604-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Thus, the concept of Sejahtera is not merely

understood economically (Suharto, 2014). The

varying conceptual definitions of Sejahtera within

society indicate a fluid and relative understanding of

the concept (Widyastuti, 2012). The concept is

inseparable from the societal quality of life because

factors like the socio-political along with economical

ones have a significant impact on public life

(Widyastuti, 2012). Magrabi et al. (in Sari & Pratiwi,

2018) stated that Sejahtera is defined as a state in

which an individual is in good health, comfortable,

and generally happy. We can then conclude that

Sejahtera is also closely related to a person’s well-

being, affecting factors like happiness and life

satisfaction.

Many studies have been trying to transvalue

cultural values, welfare, and well-being, especially in

the field of anthropology (see Graeber, 2001,

Lambek, 2008; Otto & Willersev, 2013; Robbins &

Siikala, 2014, Soas & Marsden, 2018; Tsing, 2013).

Questions and discussions about physical materials,

prosperity, crises in financial, economic, social, and

political, as well as happiness and well-being begin to

rise (Coleman, 2004; Johnston, 2012; Soas &

Marsden, 2018). These studies focused on the

recommendation that the study of welfare (Sejahtera)

and well-being should depart from the contextual

meaning.

What is peculiar about Indonesia’s condition is

that while the country is perceived to have a level of

Sejahtera or prosperity that can be considered to be

on the lower end, World Happiness Report 2020 had

stated that Indonesia was ranked decently high on the

happiness scale (ranking 84

th

out of 153 countries

with a score of 5.3 out of 10). This phenomenon

elicits some assumptions; one possibility is that the

level of Sejahtera within the people of Indonesia is

inversely proportionate to the level of happiness,

another possibility would be to assume that Sejahtera

is not a determining factor in determining happiness.

Previously Sejahtera was defined as the fulfilment of

economical and psychological aspects closely related

to well-being. However, these definitions do not

explain the apparent existing gap between a high level

of happiness and a low level of Sejahtera. This raises

the question, how is the concept of Sejahtera

understood by the people of Indonesia? Is Sejahtera

understood predominantly as an economical concept

(e.g., Sejahtera when economical needs are fulfilled)?

Or does it lean more toward well-being (e.g.,

Sejahtera when one feels happy, at peace, in a

tranquil state, etc)?

Semantic study to interpret the meaning of

Sejahtera for Indonesians is necessary since every

culture has its standards of what can be considered as

being prosperous. The meaning of abstract concept

such Sejahtera is closely related to what society

defined as a state where their life is prosperous, or

when everything is fulfilled. But what is it that being

fulfilled? This definition cannot be determined by

other cultures which have different values, different

ways of living, and different standards of living

(Hakim, 2014). As Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan

(2010) stated that many claims or research

conclusions about human psychology were based on

what they called WEIRD (Western, Educated,

Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies and

these societies cannot represent the other populations.

Generally, the objective of this research is to

explore how the people of Indonesia understand and

perceive the concept of Sejahtera. Mirroring previous

studies which had understood Sejahtera from two

aspects, economical along with well-being, the

participants’ level of well-being is also measured,

which were subjective happiness and life satisfaction.

On the other hand, to include the economical side of

Sejahtera, saving habits are also measured. The habits

of saving money differ across cultures and it is related

to the level of prosperity of the country (Imron, 2012;

Kim, Yang & Hwang, 2006; Putong, 2010). We

assume that people who have a habit of saving their

income (Chavali, 2020) would perceive Sejahtera

differently from those who are not. In other words,

this research is done not only to understand the

holistic view of how Indonesian society understands

and perceives the concept of Sejahtera, but also to see

(if any) a variety of understanding relating to

differences in levels of happiness, life-satisfaction, as

well as saving habits.

We assumed that people who scored high on the

happiness or life-satisfaction scale would have

generated a different meaning of Sejahtera compared

to people who are unhappy or dissatisfied. Further,

we are also interested to examine whether Sejahtera

would be perceived differently based on people’s

saving habits, that is participants who have a habit of

saving their incomes would give different meanings

toward Sejahtera compared to those who do not have

the habit to save money.

2 METHODS (AND MATERIALS)

To investigate how Indonesians perceive Sejahtera, a

feature generation task was employed to generate

features that describe the meaning of Sejahtera. Their

level of happiness (using Subjective Happiness Scale)

and life-satisfaction (using Satisfaction with Life

What Does Sejahtera Mean to You? The Interpretation of Sejahtera based on Money-saving Habit, Happiness, and Life Satisfaction

367

Scale) was measured, as well as their money-saving

habit (e.g., whether they have a saving habit, the

percentage of saving from salary, and whether this is

a routine habit). The generated features were grouped

based on participants’ level of well-being and saving

habit. We assumed that people who were happy and

satisfied would perceive Sejahtera differently

compared to people who were unhappy and

dissatisfied. Further, we also thought that saving

habits would affect how people give meaning to

Sejahtera. In other words, people with saving habits

would have a different understanding of Sejahtera in

comparison with people who do not.

2.1 Ethics Statement

This study was conducted with the approval of the

Research Ethics Committee of the Department of

Psychology, University of Bina Nusantara. Written

informed consent was obtained from all participants

before starting the task.

2.2 Participants

A total of 334 Indonesians (190 females and 144

males) adult participants participated in this study.

Participants’ age ranged from 14 to 60 (M = 26.12,

SD = 10.77). Three participants were excluded from

the analysis because there were under 18 years old

(one participant aged 14, 15, and 16; they were all

male participants), resulted in 331 participants in the

analysis. All participants did the study voluntarily and

received no compensation for their participation.

2.3 Materials

The materials used for this research were a four-part

questionnaire which consisted of the Sejahtera

questionnaire, the Subjective Happiness Scale

questionnaire (SHS; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999),

the Satisfaction with Life Scale questionnaire (SwLS;

Diener et al., 1985), and the saving habits

questionnaire.

The first part of the questionnaire was the feature

generation task to see how Indonesians perceive and

give meaning to the concept of Sejahtera. Here the

participants were asked questions like “What is

Sejahtera for you?” Participants were asked to give a

minimum of three answers and a maximum of 10

(conceptions of what Sejahtera is).

Next, the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS;

Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1997) was utilized to

measure the happiness level of the participants. This

questionnaire consisted of four items and had been

adapted to Bahasa Indonesia (Rumondor & Djalal,

2020). Using Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient,

a score of 0.64 was obtained. The scale asked

participants to rate how appropriate each statement

was to each of their conditions using a scale of 1 to 7.

The higher the score, the higher their happiness level.

Life satisfaction was then measured with the

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SwLS; al., 1985) which

consisted of five items that had also been adapted to

Bahasa Indonesia (Rumondor & Djalal, 2020). The

reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha

reliability coefficient and the results revealed 0.76.

For each item, participants were asked to rate

themselves on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7

(strongly agree). The higher the score, the more

satisfied they are with life.

Lastly, three questions were asked in regards to

saving habits after participants filled out their

demographical details. Participants were asked to

indicate whether they had a saving habit, the

percentage of their salary that was saved, as well as

whether this behaviour was part of their routine. Their

answers were then used to investigate differences in

their conceptions of Sejahtera.

2.4 Procedures

First, all participants were given a link to an online

survey. The link was broadcasted to a variety of social

media like WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, and

Instagram. The online survey provided potential

participants with information in regards to the

objective of this research. Afterward, they were asked

to give their informed consent. If they agreed to

participate, they would then be asked for their

demographic details (gender, age, education,

occupation, and salary). The participants were then

asked to read the instructions on how to properly fill

in the feature generation task. After the participants

finished reading the instructions, they were then

asked to start filling in their answers of how they give

meaning to the concept of Sejahtera. Afterward, the

participants were asked a series of questions about

their saving habits before continuing to the Subjective

Happiness Scale (SHS) and the Satisfaction with Life

Scale (SwLS). All items were provided in a consistent

order. The entire survey was in Bahasa Indonesia and

there was no time limit.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

368

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

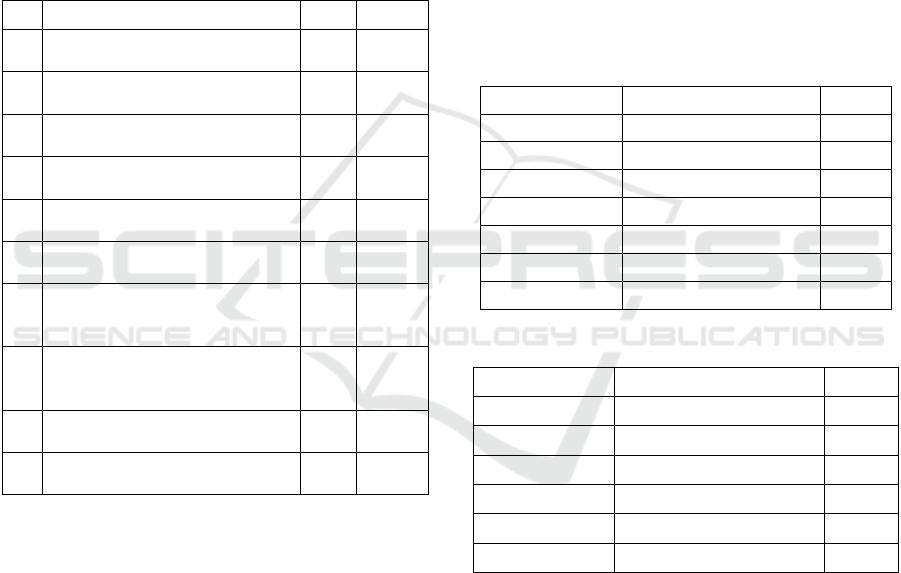

3.1 The Top 10 Features

As many as 1,331 features were produced for the

concept of Sejahtera, all of which came from the

feature generation task. All of the features were then

counted for frequency. Table 1 below shows the top

10 features that were produced for the concept of

Sejahtera. As shown in Table 1, the most generated

feature was merasa bahagia (feeling happy). In other

words, Indonesian society perceived Sejahtera

largely as a happy feeling.

Table 1: The 10 most generated features.

Features N %

1

Feeling happy

merasa bahagia

152 11,4%

2

Having enough

tercuku

p

i

138 10,4%

3

Having every need fulfilled

s

egala sesuatu terpenuhi

93 7,0%

4

Feeling peaceful

merasa damai

84 6,3%

5

Feeling safe

merasa aman

61 4,6%

6

Feeling prosperous

merasa makmu

r

59 4,4%

7

Having a good grasp on all of

life’s problems

s

emua beban masalah terkendali

54 4,1%

8

Having every expectation

fulfilled

s

emua terca

p

ai

53 4,0%

9

To feel at peace

merasa tentram

49 3,7%

10

To be in good health keadaan

s

ehat

48 3,6%

As can be seen from Table 1, the two most

generated features were related to both sides of a coin

(Friedlander & Robert, 1982; Widyastuti, 2012),

namely Sejahtera was perceived as well-being

(feature ‘Feeling happy’) and as an economical

concept (feature ‘Having enough’). The rest of the

features are mostly a combination of the two.

However, looking at it closely, in general, these

features focused on the self. Corroborated with

Widyastuti (2012), some of them revolved around the

feeling, that is Sejahtera perceived as when one feels

happy, peaceful, safe, and prosperous. The others

focused on something that one-self can achieve:

having every need fulfilled, having no problems,

being in a good health. This seemed to suggest that,

even though Indonesian is considered to have a

collective culture (Irawanto, 2009), but when it comes

to being prosperous as a state, Indonesians feel that

Sejahtera is personal, something that can affect and

can be achieved by one-self.

3.2 The Top Features based on the

Well-Being Levels

The participants’ happiness and life satisfaction were

measured to investigate whether participants with

different levels of well-being were producing features

that were also different. The average score of each

participant was measured for both well-being scales

and was grouped based on each scale’s norm. Table 2

and 3 shows the classification of each scale as well as

the number of participants for each level of happiness

and life satisfaction.

Table 2: The classification of subjective happiness.

Average Score

SHS N

6.1 – 7.0 Extremely happy 0

5.1 – 6.0 Happy 107

4.1 – 5.0 Slightly happy 504

4.0 Neutral 144

3.1 – 3.9 Slightly unhappy 497

2.1 – 2.9 Unhappy 69

1.0 – 2.0 Extremely unhappy 10

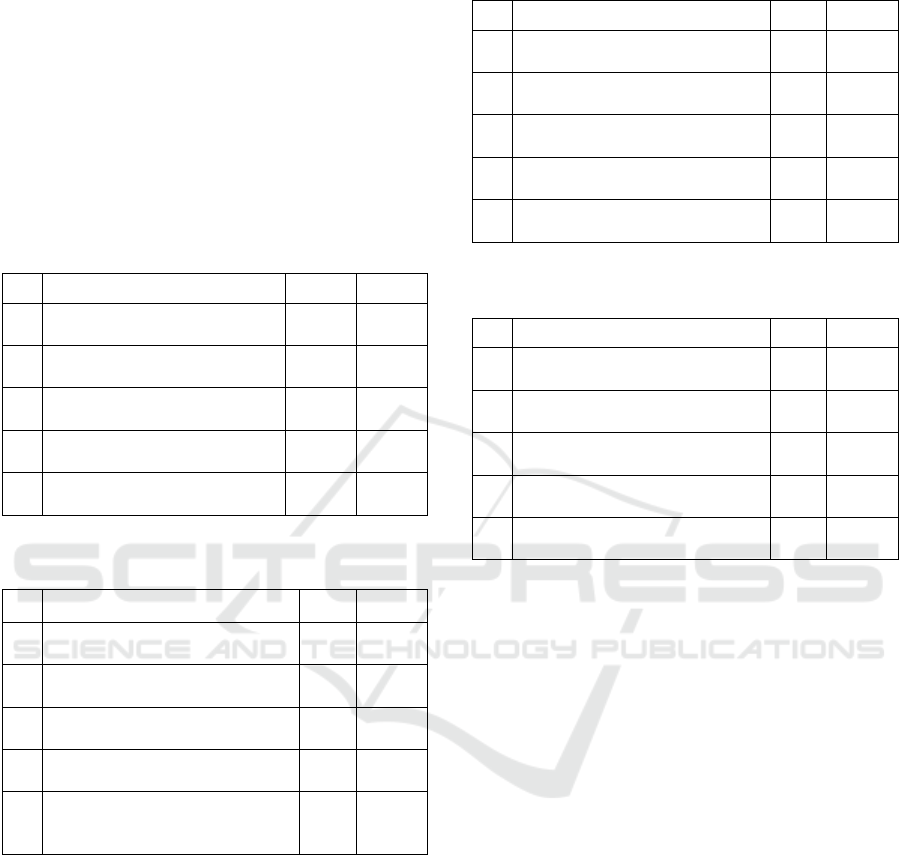

Table 3: The classification of satisfaction with life.

All features that were produced were now

grouped based on each participants’ score for each

scale. To simplify things, the 5 most produced

features are shown based on two spectrums; Happy-

Unhappy and Satisfied-Dissatisfied with the

following details: participants that scored anything

above 4.0 (Extremely Happy/Satisfied, Slightly

Happy/Satisfied, and Happy/Satisfied in both the

SHS and the SwLS respectively) were categorized as

one group labeled ‘Happy’ in the SHS scale and

‘Satisfied’ in the SwLS. The 5 most generated

features produced by ‘Happy’ participants are shown

Average Score SwLS N

6.1 – 7.0 Extremely satisfied 148

5.1 – 6.0 Satisfied 317

4.1 – 5.0 Slightly satisfied 413

4.0 Neutral 71

3.1 – 3.9 Slightly dissatisfied 255

2.1 – 2.9 Dissatisfied 110

What Does Sejahtera Mean to You? The Interpretation of Sejahtera based on Money-saving Habit, Happiness, and Life Satisfaction

369

in Table 4, and the 5 most generated features

produced by ‘Satisfied’ participants are shown in

Table 5. On the other hand, those who scored lower

than 4.0 (Extremely Unhappy/Dissatisfied, Slightly

Unhappy/Dissatisfied, and Unhappy/Dissatisfied on

the SHS and SwLS) were categorized as one group

labelled ‘Unhappy’ in the SHS and ‘Dissatisfied’ in

the SwLS. The 5 most generated features produced by

the ‘Unhappy’ group are shown in Table 6, and the

top 5 features produced by the ‘Dissatisfied’ group

are shown in Table 7.

Table 4: The top 5 features generated by the ‘Happy’

participants who scored above 4.0 on SHS.

Features N %

1

Having enough

tercuku

p

i

68 11,1%

2

Feeling happy

merasa bahagia

66 10,8%

3

Having every need fulfilled

s

e

g

ala sesuatu ter

p

enuhi

50 8,2%

4

Feeling peaceful

merasa damai

35 5,7%

5

Feeling prosperous

merasa makmu

r

26 4,3%

Table 5: The top 5 features generated by ‘Satisfied’

participants who scored above 4.0 on SwLS.

Features N %

1

Feeling happy

merasa baha

g

ia

97 11,0%

2

Having enough

tercukupi

68 7,7%

3

Having every need fulfilled

s

e

g

ala sesuatu ter

p

enuhi

63 7,2%

4

Feeling peaceful

merasa damai

56 6,4%

5

Having every expectation

fulfilled

s

emua terca

p

ai

20 2,3%

As shown in Table 4 and Table 5 those who scored

high on the SHS and SwLS produced highly similar

features except for one. Further, there seemed to be a

unanimous conclusion that the feeling of ‘Sejahtera’

is obtained when feeling happy. These results seem to

suggest that there are no differences between people

who are happy and satisfied in perceiving Sejahtera.

In other words, people who are scored high in their

well-being levels seemed to value Sejahtera both

from the economical point of view (Friedlander &

Robert, 1982) as well as positive affect (Suharto,

2014; Widyastuti, 2012; i.e., happy, peaceful, and

feeling prosperous).

Table 6: The top 5 features generated by the ‘Unhappy’

participants who scored lower than 4.0 on SHS.

Features N %

1

Feeling happy

merasa bahagia

68 11,8%

2

Having enough

tercukupi

59 10,2%

3

Feeling peaceful

merasa damai

30 5,2%

4

Feeling safe

merasa aman

31 5,4%

5

Having every need fulfilled

s

e

g

ala sesuatu terpenuhi

29 5,0%

Table 7: The top 5 features generated by the ‘Dissatisfied’

participants who scored lower than 4.0 on SwLS.

Features N %

1

Having enough

tercukupi

40 10,5%

2

Feeling happy

merasa baha

g

ia

39 10,2%

3

Feeling safe

merasa aman

19 5,0%

4

Feeling peaceful

merasa damai

19 5,0%

5

Feeling prosperous merasa

makmu

r

18 4,7%

As shown in both Table 6 and 7, the composition

of the 5 most produced features was very similar

between the ‘Unhappy’ and ‘Dissatisfied’

participants and the ones produced by the ‘Happy’

and ‘Satisfied’ ones. In both, the features ‘feeling

happy’ and ‘having enough’ consistently stayed on

first and second place across all Tables. It can be

concluded, unexpectedly, that there are no differences

in perceiving the concept of Sejahtera between

Happy/Satisfied participants and

Unhappy/Dissatisfied ones. It seems that Indonesians

thought about the ideal condition when they were

asked to define Sejahtera, despite their well-being

levels.

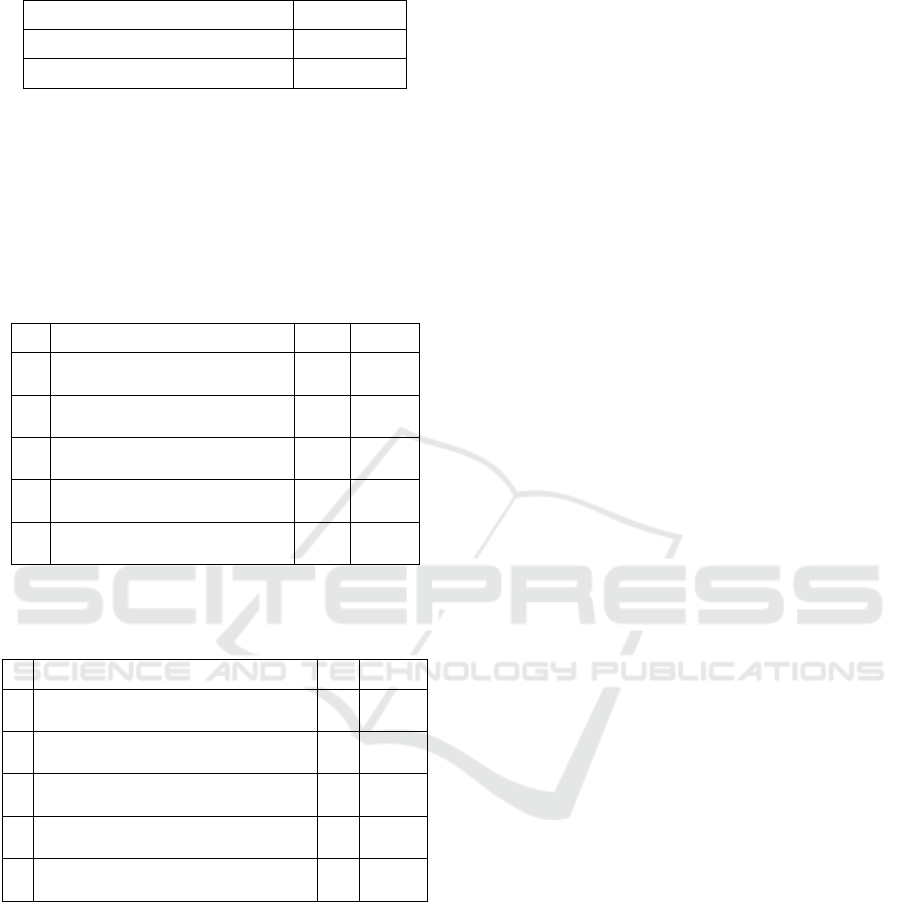

3.3 The Top Features based on Saving

Habit

To investigate whether participants who had a

money-saving habit perceived Sejahtera differently

than those who did not, their differences were

measured. The average score of each participant was

measured regarding whether they had a saving habit.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

370

Table 8: The percentage of people based on saving habit.

Saving habit N

Yes, I have 283

No, I do not save money 48

As shown on both Table 9 and 10, the composition

of the 5 most generated features between those who

had a saving habit and those who did not, were nearly

identical. In both, the features ‘feeling happy’,

‘having enough’, and ‘having every need fulfilled’

were ranked first, second, and third, respectively.

Table 9: The 5 most generated features produced by the

participants based on their saving habit ‘Yes, I have’.

Features N %

1

Feeling happy

merasa baha

g

ia

136 11,5%

2

Having enough

tercukupi

123 10,4%

3

Having every need fulfilled

s

e

g

ala sesuatu ter

p

enuhi

80 6,8%

4

To feel at peace

merasa damai

78 6,6%

5

Feeling safe

merasa aman

55 4,7%

Table 10: The 5 most generated features produced by the

participants based on their saving habit ‘No, I do not save

money’.

Features N %

1

Feeling happy

merasa bahagia

16

10,5

%

2

Having enough

tercukupi

15 9,9%

3

Having every need fulfilled segala

s

esuatu ter

p

enuhi

13 8,6%

4

Having a lot of money memiliki

banyak uang

10 6,6%

5

Having no debts

tidak memiliki hutang

7 4,6%

It can be concluded that there are not any

meaningful differences in perceiving the concept of

Sejahtera between those who had a saving habit and

those who did not. However, people who had a saving

habit seem to focus on feeling peaceful and safe,

where people who did not, focused on the ideal

condition, that is having lots of money and have no

debts. This might be because, people who saved their

money already feel safe and at ease, conditions that

they have achieved. Whereas those who do not have

savings, yearn for an ideal condition that is normally

achieved by people who had savings, that is having a

lot of money and no debts.

3.4 Features Related to Sejahtera

Definition According to the

Indonesian Law

The concept of Sejahtera has a legal definition in

Indonesia. Referring to No. 6 of the 1974 constitution

of the Republic of Indonesia concerning to provisions

within the context of Pokok Kesejahteraan Sosial

(roughly, The Fundamentals of Social Prospering);

Kesejahteraan Sosial is a deliberately established

pattern of life cultivating both social, material, as well

as spiritual aspects which are predominantly guided

by feelings of safety, decency, as well as a peace of

both body and mind that enables every citizen of

Indonesia to develop and cultivate efforts to fulfil

their physical, religious, as well as social needs to the

best of their abilities for each individual, family, and

the broader society predicated upon human rights in

accordance to Pancasila (Indonesia’s core philosophy

as both a state and a people).

Pearson correlation was executed to investigate

whether there were significant relations between the

features generated by participants based on saving

habits and the legal definition of the concept of

Sejahtera. In other words, to see whether participants

with saving habits tended to produce features that

were more related to the legal conception of

Sejahtera, and vice-versa. The results showed no

significant correlation (r = 0.02, p = .79) between

saving habits and generated features that were related

to the law. This revealed that whether an individual

had a saving habit did not influence whether their

understanding of the concept of Sejahtera was more

related to its legal definition. Regardless of whether a

person had a saving habit, they still might have

varying perceptions about the concept of Sejahtera.

Understanding the concept of Sejahtera had nothing

to do with saving habits. In the sense that saving

behaviour is not essential for Indonesian society in

determining their views on the concept of Sejahtera.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This research was done to provide a broad overview

of the perception of Indonesian society toward the

concept of Sejahtera. The results showed that despite

having some idiosyncratic features, Sejahtera was

perceived uniformly among Indonesians as ‘feeling

happy’, ‘having enough’, and ‘having every need

fulfilled’. These features were generated most often

by participants regardless of their level of happiness,

life satisfaction, and their saving habit.

What Does Sejahtera Mean to You? The Interpretation of Sejahtera based on Money-saving Habit, Happiness, and Life Satisfaction

371

The different perceptions of Sejahtera in this

research were analysed from the perspective of well-

being, which consisted of happiness and life

satisfaction. They were also analysed based on saving

habits. The differing (or lack thereof) understanding

of the concept of Sejahtera was investigated based on

whether an individual had saving habits, as well as

whether they were considered happy or unhappy and

whether they were satisfied with their life.

It can be seen from what had been explicated

beforehand that there was no significant difference in

perceptions toward the concept of Sejahtera

regardless of an individual’s happiness or life

satisfaction level. The same holds for saving habits,

no significant difference in perceiving and

understanding the concept of Sejahtera regardless of

whether their money saving habits.

Taking everything into account, it also interesting

to notice that since Sejahtera was perceived

uniformly regardless of their well-being levels and

saving habits, seeing the most generated features,

seems to suggest that Indonesians perceived

Sejahtera as an ideal state, a condition that they

believed to be prescriptively ideal, not as a factual

condition (Bear & Knobbe, 2017). The generated

features seem to reflect a condition that people are

eager to achieve despite their actual condition. For

instance, the most generated features taken from the

people who do not have saving habit were ‘Having

every need fulfilled’, ‘Having a lot of money’, and

‘Having no debts’ were seeming to contradict with

their actual condition that ideally can only be

achieved by people who are saving their money. The

same pattern was also found with people who scored

low on their well-being levels (See Table 6 and 7).

They generated features such as ‘Feeling happy’,

‘Having enough’, or ‘Feeling Peaceful’. These are a

condition that ideally achieved by people who are

happy and satisfied. Thus, when Indonesians were

asked to describe their understanding of Sejahtera,

they thought of an ideal condition that was driven by

the norm (in this case the law definition) in which

positive affects and prosperous conditions were

involved, and they ignored their actual condition.

That explains the uniformity we found across

participants in perceiving Sejahtera as an ideal

condition that people willing to achieve.

Further study could explore the differences on

how being prosperous or Sejahtera was perceived

across different cultures (and languages).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

HFZ and S are currently last year undergraduate

students of Psychology at Bina Nusantara University.

FMD and YDP are lecturers at Bina Nusantara

University. All five authors discussed the findings

thoroughly, read, and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Bear, A., & Knobe, J. (2017). Normality: Part descriptive,

part prescriptive. Cognition, 167, 25–37. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2016.10.024

Chavali, K. (2020). Saving and spending habits of youth in

sultanate of oman. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(2),

718-719. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.02.132

Coleman, S. (2004). The charismatic gift. Journal of the

Royal Anthropological Institute, 10 (2), 421-442.

Djalal, F. M., & De Deyne, S. (2021, April 07). Studi

asosiasi kata. https://smallworldofwords.org/id/

Diener, E., Scollon, C. N., & Lucas, R. E. (2009). The

evolving concept of subjective well-being: The

multifaceted nature of happiness. In E. Diener (Ed.),

Assessing Well-Being (pp 67-100). Dordrecht:

Springer.

Fahrudin, A. (2012). Pengantar Kesejahteraan Sosial.

Bandung: PT Refika Aditama.

Friedlander, W. A. & Robert A. Z. (1982). Introducing

Sosial Walfare. New Delhi: Prentice-Hall of India

Publications.

Graeber, D. (2001). Toward an anthropological theory of

value. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Hakim, L N. (2014). Ulasan Konsep: Pendekatan Psikologi

Indijinus Concept Review: Indigenous Psychology

Approach. Aspirasi, 5(2), 165-172. doi:

https://doi.org/10.46807/aspirasi.v5i2.456.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The

weirdest people in the world?. Behavioral and brain

sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83. doi: 10.1017/S014052

5X0999152X

Imron, A. (2012). Manajemen peserta didik berbasis

sekolah. Jakarta: Bumi Aksara.

Irawanto, D. W. (2009). An Analysis Of National Culture

And Leadership Practices In Indonesia. Journal of

Diversity Management – Second Quarter,4(2), 41-48.

Doi: https://doi.org/10.19030/jdm.v4i2.4957

Johnston, B. (2012). On happiness. American

Anthropologist, 114 (1), 6–18. Doi: https://doi.org/

10.1111/j.1548-1433.2011.01393.x

Kim, U., Yang, K., Hwang, K. (2006). Contributions to

Indigenous and Cultural Psychology: Understanding

People in Context. Dalam Kim, U., Yang, K., Hwang,

K., (eds). Indigenous and Cultural Psychology:

Understanding People in Context. New York: Springer.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

372

Lambek, M. (2008). Value and virtue. Anthropological

Theory, 8 (2), 133–57. Doi: https://doi.org/10.117

7/1463499608090788

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1997). Measures of

subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and

construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2),

137-155. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006824100041

Otto, T, & Willersev, R. (2013). Prologue: Value as theory:

Value, action, and critique. HAU: Journal of

Ethnographic Theory, 3 (2), 1-10. Doi: https://doi.org/

10.14318/hau3.1.002

Putong, I. (2010). Economics : Pengantar mikro dan makro

(4 ed.). Jakarta: Mitra Wacana Media.

Robbins, J, & Siikala, J. (2014). Hierarchy and hybridity:

Toward a Dumontian approach to contemporary

cultural change. Anthropological Theory, 14 (2), 121-

132. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499614534059

Rumondor, P. C. B., & Djalal, F. M. (2020). Concept of

marriage in university studens: What is a marriage

anyway? Proceeding of International Conference on

Biospheric Harmony, Indonesia.

Sari, P., & Pratiwi, D. A. (2018). Faktor-faktor yang

mempengaruhi kesejahteraan hidup masyarakat

suku laut pulau Bertam kota Batam. Jurnal Trias

Politika, 2(2). 137-152. Doi: jurnaltriaspolitika/article

/view/1464/1072

Soas, R. K. & Marsden, M. (2018). Alternate modes of

prosperity. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 8

(3): 596–609. Doi: doi/full/10.1086/701215

Suharto, E. (2014). Membangun Masyarakat

Memberdayakan Rakyat (Kajian Strategis

Pembangunan Kesejahteraan Sosial & Pekerjaan

Sosial). Jakarta: PT. Refika Aditama.

Suradi. (2007). Pembangunan manusia, kemiskinan dan

kesejahteraan sosial. Jurnal Penelitian dan

Pengembangan Kesejahteraan Sosial, 12(03), 1-11.

doi: https://doi.org/10.33007/ska.v12i3.636

Tsing, A. (2013). Sorting out commodities: How capitalist

value is made through gifts. HAU: Journal of

Ethnographic Theory, 3 (1), 21 - 43. Doi:

https://doi.org/10.14318/hau3.1.003

Widyastuti, A. (2012). Analisis hubungan antara

produktivitas pekerja dan tingkat pendidikan pekerja

terhadap kesejahteraan keluarga di jawa tengah.

Economics Development Analysis Journal, 1 (2), 2-3.

doi: https://doi.org/10.15294/edaj.v1i2.472

What Does Sejahtera Mean to You? The Interpretation of Sejahtera based on Money-saving Habit, Happiness, and Life Satisfaction

373