Suicide and Narcissistic Personality Traits: A Review of Emerging

Studies

Charissa Lazarus and Khamelia Malik

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia – Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Suicide, Narcissistic, Trait.

Abstract: Suicide is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO),

there were 800,000 documented suicides worldwide in 2015. In Indonesia there were roughly 9,000 suicides

per year. Suicide is a complex phenomenon that is commonly linked with psychiatric disorders, namely

personality disorder. Evidently, emerging studies have begun to point out the role of narcissistic personality

traits in suicidal behavior, with only few studies currently reviewing this phenomenon. Therefore, we aim to

review the current literature to elucidate the link between narcissistic personality disorder and suicide. We

selected studies published in Pubmed, Scopus, Proquest databases, using keywords ‘suicid*’AND ‘narcis*’,

‘narcissistic personality’, ‘narcissistic personality disorder’, ‘narcissistic personality trait*, focusing on

narcissistic personality traits suicidal behavior, and using standardized instruments. Suicidal behavior is

associated with narcissistic personality traits, especially narcissistic vulnerability. Current evidence showed

that problems with perfectionism, emotion, self-dysregulation, self-esteem, shame, and anger as factors that

influence the link between narcissistic personality traits and suicidal behavior. Narcissistic personality traits

are associated with suicidal behavior, potentially as a marker of suicide risk. Close monitoring of this

population group may be beneficial to prevent suicides in general. Future research need to elaborate

contributions of culture and ethnicity.

1 INTRODUCTION

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death

worldwide. According to the World Health

Organization (WHO), there were 800,000

documented suicides worldwide in 2015, with more

than 79% of them occurring in low- and middle

income countries. Additionally, among 15-29 years

old, suicide is the second leading cause of death in

2016 (World Health Organization, 2019). Due to the

high burden of suicide, the World Health

Organization even declared the prevention of suicide

as the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal indicator

(World Health Organization, 2014). Suicide is a

complex phenomenon. Many studies tried to

understand suicide through the approach of

psychiatry disorders. Clinicians need a

multidimensional approach in order to understand

and determine specific suicide risk factors. The most

common axis I psychiatry disorder associated with

suicidal behavior is mood-related disorders. In

addition, clinicians and researchers observe that

personality disorders are also related to suicidal

behavior. (Boisseau et al., 2013; Pompili et al., 2004).

Personality is a complex pattern of ingrained

psychological characteristic. It is also intrinsic,

pervasive and enduring in one’s lifetime. Personality

is analogous to the immune system of the mental

state, it will determine how well a person cope with

stressors and negative life events. Disorder of the

personality will make a person susceptible to stressors

that can ultimately lead to psychiatry disorders and

suicidality (Millon, 2016; Millon et al., 2004). So, it

is imperative to consider personality disorders and

traits in the assessment of suicidality.

The association between personality disorders and

suicidality suggests that personality pathology may

reflect critical individual differences in predicting

suicide attempts (Ansell et al., 2015). One of the well-

known personality disorders linked with suicidality is

borderline personality disorder. Meanwhile, many

believe narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) or

narcissistic personality traits (NPT) are negatively

related to suicidal behavior. There is also a

widespread belief that when a person with NPD or

NPT said they want to commit suicide, it is only a

254

Lazarus, C. and Malik, K.

Suicide and Narcissistic Personality Traits: A Review of Emerging Studies.

DOI: 10.5220/0010749500003113

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Technology, Engineering and Science (ICE-TES 2021), pages 254-264

ISBN: 978-989-758-601-9

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

gesture or form of manipulation (L, 2016).

Interestingly, emerging studies began to point out the

role of NPD and NPT in suicidal behavior and

showed that individual with NPD and NPT are

vulnerable to suicidality compared to general

population. Unfortunately, only a few studies are

reviewing this phenomenon. Therefore, this paper

aims to review the association between NPD and or

NPT with suicidal behavior. We will also attempt to

explain the mechanism underlying the phenomenon

from the current available literature.

2 METHOD

We selected research studies published in Pubmed,

Scopus, Proquest databases using keywords

‘suicid*’, ‘suicidal’ ‘suicidal behavior’ AND

‘narcis*’, ‘narcissistic’, ‘narcissistic personality’,

‘narcissistic personality disorder’, ‘narcissistic

personality trait*’, ‘narcissism’ focusing on

narcissistic personality disorder or narcissistic

personality traits and suicidal behavior, including

ideation, attempts or completion, and using

standardized instruments. In addition we searched for

the epidemiology of suicide and suicidal behavior.

We also searched the reference lists of retrieved

articles for additional relevant articles.

3 DISCUSSION

3.1 Narcissistic Personality Disorders

and Narcissistic Personality Traits

The needs of admiration, validation, and self-

enhancement are standard features of personality. It

is common for individuals to strive a positive self-

image, seek self-enhancement experience or

achievements. It is normal when individuals can

manage the needs effectively, behave in socially

acceptable ways, and regulate negative emotions and

behavior when experiencing disappointment. On the

other hand, the traits became pathological when they

are extreme, and the individual has an impaired

regulatory capacity to satisfy the needs of admiration,

validation, or recognition. It became pathological

when the individual behavior is socially unacceptable

and fails to regulate negative emotions and behavior

when facing the unmet need (Pincus et al., 2014;

Roche et al., 2013).

According to the American Psychiatric

Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), the

essential feature of narcissistic personality disorder is

a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, need for

admiration, and lack of empathy that begins in early

adulthood and is present in a variety of life’s

circumstances (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM-5®), 2013). Although these

criteria describe essential aspects of narcissistic

pathology, they inadequately describe the core

psychological feature of the disorder, including

fragile self-esteem, feelings of inferiority, emptiness,

and affective reactivity (Ronningstam, 2009). Many

authors support the existence of different subtypes of

narcissistic personality disorder. Some researchers

suggest that narcissism might not be a single

construct (Zajenkowski et al., 2018). A study from

Cain et al. identified approximately 50 labels

describing expressed variability of pathological

narcissism, divided into two broad themes of

narcissistic dysfunction: narcissistic grandiosity and

narcissistic vulnerability. They concluded that there

were distinctive features between the two in self-

structure, difficulties in the therapeutic relationship,

and maladaptive defensive strategies used to respond

to stressors such as shame, trauma, unfulfilled needs,

dependency, or abandonment depression (Pincus &

Lukowitsky, 2010). Each dimension has its distinct

characteristic yet share the same narcissistic common

core such as exaggerated sense of self-importance,

disagreeableness, self-centredness, entitlement, and

an antagonistic manner interpersonally (Miller et al.,

2017; Zajenkowski et al., 2018).

Narcissistic grandiosity is a typical presentation

of narcissistic personality disorder. Individuals with

narcissistic grandiosity are characterized by overt

grandiosity, high self-esteem, and a tendency to

overestimate one’s capability (Zajenkowski et al.,

2018). Interpersonally, they show the trait of

attention-seeking, entitlement, arrogance, socially

charming, oblivious to the needs of others, and are

interpersonally exploitative (Pincus & Lukowitsky,

2010). On the contrary, individuals with narcissistic

vulnerability presents defensive, avoidant,

hypersensitive, hypervigilant to criticism, and

insecure features. Interpersonally, they are often shy,

hypersensitive to evaluations, manifestly distressed

but have secret grandiosity, chronically envious dan

ceaselessly comparing themselves with others

(Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010). They tend to rely more

on external feedback to maintain their self-esteem and

experience greater shame when the expected external

feedback is unmet (Besser & Priel, 2010). Individuals

with vulnerable narcissism have a greater risk of

psychological distress and negative emotions,

Suicide and Narcissistic Personality Traits: A Review of Emerging Studies

255

including anxiety, depression, anhedonia, and low

self-esteem (Loeffler et al., 2020; Marčinko et al.,

2014; Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010). However, these

features were not mutually exclusive to one another.

Individuals with narcissistic personality traits were

found to have a varying intensity of both dimensions

of narcissism. Clinicians observed that people with a

narcissistic personality disorder often show both

vulnerable and grandiose narcissism in a fluctuating

manner (Caligor et al., 2015; Gabbard, 2014). Gore

and Widiger found that individuals with grandiose

narcissism showed some aspect of vulnerable

narcissism at some period. Meanwhile, an individual

with vulnerable narcissism rarely showed the trait of

grandiose narcissism (Gore & Widiger, 2016).

Therefore, contrary to the conventional view on

narcissism, this personality trait may hide a fragile

inner-self which predisposes to suicidal behaviors.

3.2 Narcissistic and Suicidal Behavior

Studies suggest that both narcissistic personality

disorders and narcissistic personality traits are

associated with suicidal behavior. A 15-year follow-

up study of patients admitted to a psychiatric ward

showed that patients with NPD or NPT were more

likely to die from suicide compared to individuals

without NPD or NPT (Stone, 1989). Brioschi et al.

(2019) investigated the role of narcissistic personality

trait in suicidal behavior of admitted psychiatric

patients with mood disorders. This study categorized

NPT to grandiose narcissism and vulnerable

narcissism with Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory-

Short Form (FFNI-SF) to measure both narcissism

traits, and used the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation

(SSI) to assess the level of suicidal ideation. The

study found that narcissistic grandiosity had a

significantly negative association with the number of

previous suicide attempts. Meanwhile, the

narcissistic vulnerability had a significant positive

association with the total SSI score, reflecting higher

suicidal behavior. The author concluded that

grandiose aspects of narcissism such as a sense of

superiority, arrogance, and dominant behavior were a

protective factor against repeated suicide gesture. The

study also argued a susceptibility to self, and

emotional dysregulation in narcissistic vulnerability

led to suicidal ideation (Brioschi et al., 2019).

Another study tried to investigate the role of shame in

the association between narcissistic personality traits

and suicidal behavior. Individuals with narcissistic

vulnerability showed a moderate to a strong positive

association with the experience of shame, particularly

characterological and bodily shame. The study also

found that narcissistic vulnerability was positively

associated with acute suicidal ideation (Jaksic et al.,

2017). One study examined the association between

narcissistic personality disorder and suicidal behavior

through dysfunctional belief. They define the

narcissistic dysfunctional belief as believing that

oneself is special and manifesting self-aggrandizing

and manipulative behavior. Interestingly, they found

that individuals with narcissistic dysfunctional beliefs

were more likely to attempt suicide (Ghahramanlou-

Holloway et al., 2018). All things considered,

narcissistic personality disorder and narcissistic

personality traits are associated with suicidal

behavior, particularly narcissistic vulnerability.

Nevertheless, a study conducted by Coleman et al.

(2017) found a different result. They found that

people with NPD were less likely to make a suicide

attempt, but the author recognized some limitations

from their study, such as the modest sample size and

the cross-sectional data. The measurements of

narcissistic personality disorder were done by

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 2

(SCID-II), which did not distinguish NPD

dimensions into narcissistic grandiosity and

narcissistic vulnerability (Coleman et al., 2017).

Therefore, perhaps their negative results were due to

the heterogeneous group of individuals with NPD

being evaluated.

Narcissistic personality disorder also has a

distinct and unique suicidal behavior characteristic.

Individuals with NPD were less impulsive in having

suicide gestures but had a higher incidence of a lethal

suicide attempt (Blasco-Fontecilla et al., 2009).

Heisel et al. (2007) found the severity of suicidal

behavior was significantly higher with older people

having NPD or NPT. The study concluded that

pathological narcissism makes them susceptible to

negative feelings due to diminished intellectual

capacities, social roles, and body-related limitations

and imperfections (Heisel et al., 2007). Study by

Garcı´a-Nieto et al (2014) showed that patients with

NPD had a distinct suicidal behavior characteristic

among other cluster B personality disorder. The

suicidal behavior in which individuals with NPD

engage are characterized by higher expected lethality

with reported motivation such as “To stop bad

feelings” (García-Nieto et al., 2014). This study also

strengthen by Giner et al (2013) who investigated

factors determining suicide completer from suicide

attempter and found that NPD was a significant factor

associated with completed suicide (Giner et al.,

2013). One research in military sample showed that

individuals with stronger narcissistic feature were

associated with a greater number of suicide attempts

ICE-TES 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Technology, Engineering, and Science

256

and may have serious intention to act upon their

suicide thoughts (Ghahramanlou-Holloway et al.,

2018). Another study also found and discussed abrupt

suicide without self-disclosure in the individual with

NPD without a major DSM-IV mental illness

(Ronningstam et al., 2008). These findings give us the

illustration that individuals with pathological

narcissism are less likely to make suicide threats and

random non-lethal suicide attempts. They are also at

high risk for completed suicide without warning signs

or self-revealing. Therefore, identifying narcissistic

personality disorder or narcissistic personality traits

in patients is critical to predict these group’s behavior

of suicide gesture.

3.3 Contributing Factors in the

Association between Narcissistic

Personality Traits and Suicidality

We notice some factors which play an essential role

in suicidality and narcissistic personality traits.

3.3.1 Association with Other Psychiatric

Disorder

According to DSM-5, narcissistic personality

disorder may be associated with depressive

symptoms, persistent depressive disorder

(dysthymia), hypomanic mood, and substance abuse

disorder (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM-5®), 2013). Some studies

stated that narcissistic vulnerabilities significantly

associated with depressive symptoms and intruisive

negative emotions (Kealy et al., 2020; Marčinko et

al., 2014). Factors such as emotion dysregulation,

preoccupation with self-image, mistrust, and negative

view of the future made this group vulnerable to

depressive symptoms (Kealy et al., 2020).

3.3.2 Perfectionism

Many studies suggest narcissism is linked with

perfectionism. Theoretically, perfectionism is a style

of thinking, behaving, and relating in individuals with

narcissistic traits, enhancing self-esteem and

grandiose self-image. On the other hand,

perfectionism has a role in suppressing negative

feelings of self-criticism, inadequacy or inferiority,

and feelings of shame (Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020;

Smith et al., 2016). Perfectionism is a personality trait

that has rigid standards for performance, overly

critical self-evaluation, and concerns about receiving

negative evaluation from others (Robinson et al.,

2020). When individuals high in perfectionism fail to

meet their unrealistically high standard, they tend to

experience intense agony and depression

(Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020). This trait can also

mediate the relationship between narcissistic and

depressive symptoms (Marčinko et al., 2014).

There are three dimensions of perfectionism based

on its interpersonal aspect: self-oriented, other-

oriented, and socially-prescribed perfectionism. Self-

oriented perfectionism is setting an unrealistically

high standard upon oneself and the tendency to be

self-critical when these expectations are not met.

Other-oriented perfectionism is placing perfectionism

upon others and a tendency to be highly critical if

others do not meet these expectations. Socially

prescribed perfectionism believes that others put an

unrealistically high standard on oneself and that

others will be highly critical on oneself if one fails to

meet the expectations (Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020).

A meta-analysis found self-oriented and other-

oriented perfectionism was positively related to

narcissistic grandiosity. On the other hand, self-

oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism proved

to be common traits in individuals with vulnerability

narcissistic, where they tend to pursuit other’s

approval and validation. These individuals have a

defensive and insecure preoccupation with

performing imperfectly (Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020;

Smith et al., 2016). Socially-prescribed perfectionism

has been related to chronic depression because it is

related to high rejection sensitivity (Fjermestad-Noll

et al., 2020). It is also associated with high levels of

suicidal behavior in adolescents (Freudenstein et al.,

2012). Another meta-analysis investigating the

association between perfectionism and suicidal

behavior found that socially prescribed perfectionism

acts as a risk factor and could predict a longitudinal

increase in suicidal ideation. Perfectionistic concerns

(socially-prescribed perfectionism, concern over

mistakes, doubts about actions, and perfectionistic

attitudes) were related to suicidal ideation and

attempts. Meanwhile, perfectionistic strivings (self-

oriented perfectionism and personal standards) lead

only to suicidal ideation. These findings strengthen

the hypothesize that narcissistic vulnerability is more

at risk for more destructive suicidal behaviors (Smith

et al., 2018). Perfectionism is also related to shame

and aggression, mainly when high perfectionistic

standards are impossible to achieve. In addition,

perfectionism with hypervigilance to criticism and

fear of failure also relates to narcissistic vulnerability

(Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020).

Suicide and Narcissistic Personality Traits: A Review of Emerging Studies

257

3.3.3 Fragile Self-esteem

One of the key feature in narcissism is self-esteem

regulation. According to Rosenberg self-esteem is an

attitude, either positive or negative, toward oneself

(Rosenberg, 2015). As stated in DSM-5, individuals

with narcissistic personality disorder have a

vulnerable self-esteem that make them very sensitive

to “injury” from criticism or defeat. They may be

preoccupied with how well they perform and

regarded by others, and need a constant attention and

admiration (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM-5®), 2013). An injury to the

image of themselves and their self-esteem often

called narcissistic injury (Goldberg, 1973).

There are two forms of high self-esteem: secure

and fragile. Individuals with secure high self-esteem

have a positive attitudes toward oneself that are

realistic, solid and resistant to threat. On the other

hand, fragile self-esteem reflects feeling of self-worth

that are vulnerable to challenge and need constant

validation. There are four ways to distinguish secure

and fragile high self-esteem: defensive self-esteem,

unstable self-esteem, contingent self-esteem, and

discrepancies between implicit and explicit self-

esteem. (Zeigler-Hill, 2006).

Implicit self-esteem is consist of nonconscious

and automatic self-evaluation, derived from the

experiential system and holistic processing of

affective experiences. While explicit self-esteem is a

by product of the cognitive system through logical

analyses of self-relevant feedback and information

(Gawronski & Payne, 2010).

Study by Vater et al (2013) found that individuals

with NPD have a lower explicit self-esteem and a

discrepancies between implicit and explicit self-

esteem (Vater et al., 2013). Di Pierro et al (2016)

found that narcissistic vulnerability have a low

explicit self-esteem. They concluded that individuals

with narcissistic vulnerability consciously evaluate

themselves as worthless (Di Pierro et al., 2016).

Explicit self-esteem negatively associated with

depressive symptom, suicidal ideation and loneliness.

Discrepancies between implicit and explicit self-

esteem, particularly a higher implicit self-esteem than

explicit self-esteem, positively associated with

depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation.

Individuals with discrepant implicit-explicit self-

esteem prone to adopt perfectionism trait which in

turn can be a predispose factor for suicidal behavior

(Creemers et al., 2012).

Another way to predict fragile self-esteem is

through the assessment of contingent self-esteem,

which represents what an individual believes one

must have or do or be in order to have value and worth

as a person. This is a vulnerable way to gain self-

worth because it needs constant validation (Kernis &

Goldman, 2006). Zeigler-Hill et al (2008) found that

narcissistic vulnerability associated positively with

contingent self-esteem at several domains: physical

appearance, outdoing others in competition,

academic competence, other’s approval, family love

and support, and being a virtuous or moral person. On

the other hand, narcissistic grandiose only associated

with outdoing others in competition domain. This

result illustrate that individuals with narcissistic

vulnerability has a fragile self-esteem (Rasmussen et

al., 2018; Zeigler-Hill, 2006). Level of self-esteem in

individuals with narcissistic vulnerability is

fluctuative following interpersonal daily events

which represent its fragility (Zeigler-Hill & Besser,

2013).

Several studies found low self-esteem could

predict suicidal behavior at all ages (Bhar et al., 2008;

Jang et al., 2014). Those findings were duplicated in

metaanalysis study by Soto-Sanz et al (2019) that

concluded low self-esteem as a risk factor for suide

attempt. One study found entrapment as a mediator

between low self-esteem and suicidal ideation (Ren et

al., 2019).

3.3.4 Self-regulatory Dysfunction

Self-regulation is a process to initiate, maintain and

control the thought, emotions and behaviors, with the

intention of producing a desired outcome or avoiding

an undesired outcome (Strauman, 2017).

Ronningstam et al (2018) stated the sense of

subjective internal control and sense of agency are

central feature of self-regulatory in narcissistic

individuals. Threats or loss of those agency can

escalate self-enhancing efforts to avoid

overwhelming emotions such as loss of control.

Efforts to maintain the sense of control and agency

may include intense suicidal preoccupation or

ideation. For narcissistically injured patient, suicide

is perceived as an escape from a feeling of

helplessness caused by intense subjective distress or

intense negative emotion. Individuals with NPD

associating suicide to the glorification of either the

self and the suicidal act (Ronningstam et al., 2018).

3.3.5 Emotion Dysregulation

Emotion regulation is a part of self-regulation. Many

studies point emotion dysregulation as a risk factor

for suicidal behavior. Patients with NPD often have

alexithymia, the inability to recognize or describe

one’s own emotion (Ronningstam, 2017). Study by

ICE-TES 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Technology, Engineering, and Science

258

Kealy et al (2017) found alexithymia significantly

associated with aggression, risky behavior and

suicidal ideation. Individuals with NPT have

emotional intolerance that led to the act of self-

silencing. They have compromised emotional

processing, often seen in their hypervigilance style

and low tolerance of negative feelings such as

hopelessness, abandonment, and self-hatred

(Ronningstam et al., 2018). The need to attain

perfectionism can contribute to the emergence of

these negative emotions (Fjermestad-Noll et al.,

2020). Emotions affect self-esteem with the resulting

feelings of worthlessness and primitive guilt that lead

to feelings of inferiority, and insult that made psychic

injury. Therefore, to avoid negative emotions,

individuals with NPT have a strong need to control

their internal states using self-silencing and self-

distancing through suppression and

compartmentalization defense mechanism. Self-

silencing often leads to the feeling of loneliness and

isolation and tend to cause suicidal crises

(Ronningstam et al., 2018). The act of suppression

also leads individual with NPD to avoid self-

disclosure which interfere with help-seeking

behavior, thus increasing suicide risk (Ronningstam

& Weinberg, 2013). Another impact of self-silencing

and self-distancing is the feeling of emptiness.

According to the study conducted by D’Agostino et

al. (2020), individuals with NPT often experience the

feeling of emptiness and loneliness. The feeling of

emptiness could be felt in two types in narcissistic

personality disorders: primary and secondary

narcissistic emotions. The first was described as

chronic, intense envy, rage, and aggression that

belong to the more profound and split-off personality

level. The latter was the emotion that occurred when

there was an interruption in the feeding of the

grandiose self and experienced as an acute, intense,

overwhelming, and disturbing emotion that usually

not last long (D’Agostino et al., 2020).

3.3.6 Shame

Shame has been described as a central emotion in

narcissism. Shame results from a negative evaluation

of the global and stable self, elicited by perceived

failure (Ritter et al., 2014). Another literature

described shame as an intense negative emotion

involving negative feelings of inferiority, self-

consciousness, and desire to hide or disappear (Jaksic

et al., 2017). Individuals with NPT can experience

two aspects of shame: explicit shame and implicit

shame. Explicit shame is defined as a reflected

emotional response towards a negative evaluation of

self that is deliberate and can be assessed with direct

self-report measures. On the contrary, implicit shame

is an automatic, non-conscious emotional response

and is assessed indirectly. A study showed that

patients with NPD had a high level of explicit shame

and the highest level of implicit shame. One shame

regulation strategy is reported to be perfectionism

(Ritter et al., 2014). Together with perfectionism,

shame has been found to be the underlying

mechanism of maladaptive responses to negative

emotions, especially anger, self-directed hostility,

resentment, and irritability (Fjermestad-Noll et al.,

2020). Shame also put the individual at risk of sudden

suicidal crises, an acute negative cognitive and

emotional states that occurs before a suicide attempt,

unrelated to periods of mood-related disorder.

Patients with shame proneness also often become

withdrawn and does not communicate their risk for

suicide. Together with emotion dysregulation, shame

may make patient to do lethal suicide attempt with the

intent to “self-obliterate” (Links, 2013; Schuck et al.,

2019). These mechanisms led to lethal suicidal crises,

the hallmark of NPT patients.

3.3.7 Anger, Aggresivity and Hostility

Self-silencing can also be seen as a way for

individuals with NPT to have a sense of agency and

internal mastery. Threats or perceived loss of such

sense generate shame and humiliation. The sense of

failure to do self-silencing also led to anger, hostility,

and rage toward self. Self-directed rage and

aggression tend to lead the way to intense suicidal

preoccupation and determined suicidal intent

(Ronningstam et al., 2018). The association between

anger and suicidality has been studied by Lewitzka et

al. (2017) that found patients who had attempted

suicide had a significantly higher anger frequency,

angry temperament and often express their anger

more aggressively. On the other hand, patients who

had not attempted suicide had significantly lower

scores in self-aggression (Lewitzka et al., 2017). This

theory of anger and narcissistic is similar to a study

by Krizan and Johar (2015) that found anger and

hostility often arise from threats to the narcissistic

self-image, especially in individuals with narcissistic

vulnerability traits. They were prone to internalize

and externalize anger as well as poor anger control.

The study also found that vulnerable narcissism as a

strong indicator of shame and aggressiveness (Krizan

& Johar, 2015). Perfectionistic traits in patients with

NPD also cause feelings of shame and thus provoke

expressions of anger (Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020).

They concluded that the interaction between

Suicide and Narcissistic Personality Traits: A Review of Emerging Studies

259

perfectionism, shame, and aggression could

challenge self-esteem and escalate vulnerability,

therefore increasing their susceptibility to depression

(Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020).

3.3.8 Life Events

Blasco-Fonticella et al (2010) explored certain life

events precipitating suicidal behaviors in patients

with NPD. They found that narcissistic personality

disorders significantly attempted suicide after being

fired at work, increasing arguments with spouse,

personal injury or illness, and problems related to

mortgage or loan. In other words, domestic, financial,

and health problems often preceded attempted

suicide. The author argues that the association

between “being fired at work” or “increasing

arguments with spouse” may reflect the fragile

personality structure of narcissism (Blasco-Fontecilla

et al., 2010). A qualitative study by Ronningstam,

Weinberg, and Maltsberger (2008) discussed a case

of a man with NPD who faced financial losses and

divorce that killed himself without apparent warning.

This case illustrated the emotion dysregulation

phenomenon in NPD patients (Ronningstam et al.,

2008). Loses of persons or individuals of specific

importance to the person’s self-esteem, and sense of

affiliation (self-objects) can precipitate rage and

aloneness, and worthlessness and generate the

perspective of suicide as a means to escape

(Ronningstam et al., 2018). Therefore, understanding

the stressor and the following dysregulation emotion

that characterize narcissism is vital to prevent suicide

in patients with narcissistic traits.

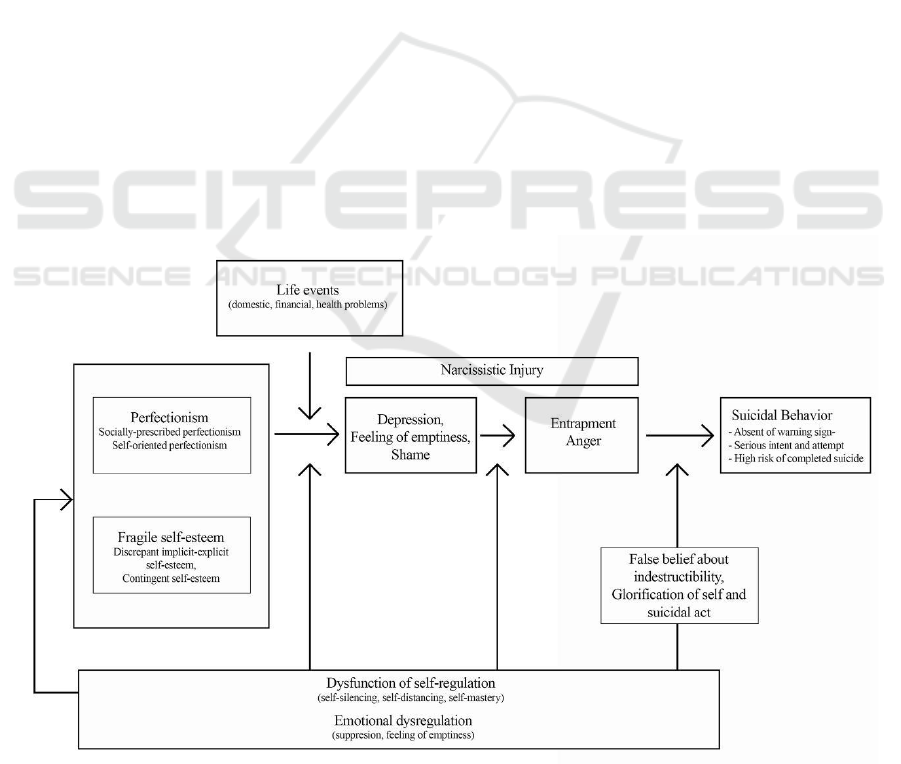

Figure 1 represent key factors between

narcissistic personality trait or disorder and suicidal

behavior. Perfectionism, notably socially-prescribed

perfectionism and self-oriented perfectionism, and

fragile self esteem, particularly discrepant implicit-

explicit self-esteem and contingent self-esteem, are

the predispose factors that make individuals

vulnerable to do suicidal behavior. If those

individuals met certain significany life events,

predispose factor prone to make these individuals feel

negative emotion such as shame, feeling of emptiness

or depressive symptom. Dysfunction of self-

regulation and emotional regulation worsen negative

emotions toward the feeling of entrapment and anger.

Perception of suicide as an escape, false belief of

indestructibility and gloficiation of self and suicidal

act move these individuals from the feeling of

entrapment and anger to adopt suicidal behavior,

consist of suicidal ideation and attempt (D’Agostino

et al., 2020; Fjermestad-Noll et al., 2020;

Freudenstein et al., 2012; Jaksic et al., 2017; Jang et

al., 2014; Loeffler et al., 2020; O’Connor & Kirtley,

2018; Ronningstam et al., 2018).

Figure 1: Suicidal behavior and narcissistic trait.

ICE-TES 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Technology, Engineering, and Science

260

3.4 Practical Implications for

Managing the Risk of Suicidal

Behavior

There are some clinical relevances and practical

implications that can be drawn from this study. First,

it is helpful for clinicians to assess the personality

profile of patients with suicidal behavior and mood

disorders. It is also helpful if clinicians could assess

which dimension of NPD or NPT patients had,

considering both dimensions have each distinct

characteristic (Pincus et al., 2014). Considering the

distinctive characteristic of suicidal behavior in

patients with NPT, clinicians should take any sign of

suicidal gesture seriously. Next, alliance building

with patients with NPT is a slow, gradual but an

essential process. Clinicians should create a sense of

safety within the therapeutic relationship to

encourage patients to learn how to regulate their

emotions and improve their ability to have a healthier

sense of agency. A good raport between clinician and

patient can promote the behaviour of self-disclose

(Links, 2013). Considering the role of shame,

clinicians can implement psychotherapeutic

interventions to handle shame proneness, such as

paying particular attention to avoid shaming words or

phrases during the therapy session. Clinicians must

avoid confronting or criticizing their grandiosity

directly. At the same time, clinicians must tend to

their insecurity and vulnerability (Jaksic et al., 2017;

Links, 2013).

Shame and perfectionism can give rise to

dysfunctional narcissistic beliefs. Targeting these

beliefs can be a part of psychosocial intervention for

patients with NPT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for

suicide prevention can be considered in the treatment

conceptualization and planning (Ghahramanlou-

Holloway et al., 2018). Clinicians should routinely

monitor the evidence of narcissistic injury in NPT

patients because they tend to hide their emotions

through self-silencing. Clinicians have to be sensitive

to the sign of withdrawal, missed sessions, sudden

guardedness, or defensive anger in NPT patients

(Links, 2013).

4 CONCLUSION

Narcissistic personality traits are associated with

suicidal behavior. Emergent studies showed that there

are two big dimensions of NPT: narcissistic

grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability. Although

suicidality was found to be associated with the two

dimensions of narcissistic, many studies found

narcissistic vulnerability to be more closely linked

with suicidal behaviour. Additionally, patients with

NPT also showed a distinctive character in their

suicidal behaviour, such as lower impulsivity, higher

lethality, abrupt suicide gesture, and a higher

probability of succesful suicide. Factors contributing

to the association between individuals with

narcissistic personality traits with suicidality are

shame, perfectionism, loneliness, isolation, feeling of

emptiness, emotion dysregulation, narcissistic injury

and anger. Understanding the nature of NPT and

contributing suicidal factors could help clinicians in

managing risk of suicidal behavior. Therefore,

profiling personality in patients especially NPT is an

imperative step in suicide prevention. Studies of

suicidal behavior in persons with narcissistic

personality traits in Indonesia are necessary for a

comprehensive suicide prevention strategy.

REFERENCES

Ansell, E. B., Wright, A. G. C., Markowitz, J. C., Sanislow,

C. A., Hopwood, C. J., Zanarini, M. C., Yen, S., Pinto,

A., McGlashan, T. H., & Grilo, C. M. (2015).

Personality Disorder Risk Factors for Suicide Attempts

over 10 Years of Follow-up. Personality Disorders,

6(2), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000089

Besser, A., & Priel, B. (2010). Grandiose narcissism versus

vulnerable narcissism in threatening situations:

Emotional reactions to achievement failure and

interpersonal rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical

Psychology, 29(8), 874–902.

https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.8.874

Bhar, S., Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M., Brown, G., &

Beck, A. T. (2008). Self-esteem and suicide ideation in

psychiatric outpatients. Suicide & Life-Threatening

Behavior, 38(5), 511–516.

https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.511

Blasco-Fontecilla, H., Baca-Garcia, E., Dervic, K., Perez-

Rodriguez, M. M., Lopez-Castroman, J., Saiz-Ruiz, J.,

& Oquendo, M. A. (2009). Specific features of suicidal

behavior in patients with narcissistic personality

disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(11),

1583–1587. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.08m04899

Blasco-Fontecilla, H., Baca-Garcia, E., Duberstein, P.,

Perez-Rodriguez, M. M., Dervic, K., Saiz-Ruiz, J.,

Courtet, P., de Leon, J., & Oquendo, M. A. (2010). An

exploratory study of the relationship between diverse

life events and specific personality disorders in a

sample of suicide attempters. Journal of Personality

Disorders, 24(6), 773–784.

https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2010.24.6.773

Boisseau, C. L., Yen, S., Markowitz, J. C., Grilo, C. M.,

Sanislow, C. A., Shea, M. T., Zanarini, M. C., Skodol,

A. E., Gunderson, J. G., Morey, L. C., & McGlashan,

Suicide and Narcissistic Personality Traits: A Review of Emerging Studies

261

T. H. (2013). Individuals with single versus multiple

suicide attempts over 10years of prospective follow-up.

Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(3), 238–242.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.07.062

Brioschi, S., Franchini, L., Fregna, L., Borroni, S.,

Franzoni, C., Fossati, A., & Colombo, C. (2019).

Clinical and personality profile of depressed suicide

attempters: A preliminary study at the open-door policy

Mood Disorder Unit of San Raffaele Hospital.

Psychiatry Research, 112575.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112575

Caligor, E., Levy, K. N., & Yeomans, F. E. (2015).

Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Diagnostic and

Clinical Challenges. American Journal of Psychiatry,

172(5), 415–422.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14060723

Coleman, D., Lawrence, R., Parekh, A., Galfalvy, H.,

Blasco-Fontecilla, H., Brent, D. A., Mann, J. J., Baca-

Garcia, E., & Oquendo, M. A. (2017). Narcissistic

Personality Disorder and Suicidal Behavior in Mood

Disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 85, 24–28.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.020

Creemers, D. H. M., Scholte, R. H. J., Engels, R. C. M. E.,

Prinstein, M. J., & Wiers, R. W. (2012). Implicit and

explicit self-esteem as concurrent predictors of suicidal

ideation, depressive symptoms, and loneliness. Journal

of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry,

43(1), 638–646.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.09.006

D’Agostino, A., Pepi, R., Rossi Monti, M., & Starcevic, V.

(2020). The Feeling of Emptiness: A Review of a

Complex Subjective Experience. Harvard Review of

Psychiatry, 28(5), 287–295.

https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000269

Di Pierro, R., Mattavelli, S., & Gallucci, M. (2016).

Narcissistic Traits and Explicit Self-Esteem: The

Moderating Role of Implicit Self-View. Frontiers in

Psychology, 7, 1815.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01815

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(DSM-5®). (2013).

Fjermestad-Noll, J., Ronningstam, E., Bach, B. S.,

Rosenbaum, B., & Simonsen, E. (2020). Perfectionism,

Shame, and Aggression in Depressive Patients With

Narcissistic Personality Disorder. Journal of

Personality Disorders, 34(Supplement), 25–41.

https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2020.34.supp.25

Freudenstein, O., Valevski, A., Apter, A., Zohar, A.,

Shoval, G., Nahshoni, E., Weizman, A., & Zalsman, G.

(2012). Perfectionism, narcissism, and depression in

suicidal and nonsuicidal adolescent inpatients.

Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(6), 746–752.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.08.011

Gabbard, G. O. (2014). Psychodynamic Psychiatry in

Clinical Practice (5th ed.). American Psychiatric

Publishing.

García-Nieto, R., Blasco-Fontecilla, H., León-Martinez, V.

de, & Baca-García, E. (2014). Clinical Features

Associated with Suicide Attempts versus Suicide

Gestures in an Inpatient Sample.

Archives of Suicide

Research, 18(4), 419–431.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.845122

Gawronski, B., & Payne, B. K. (2010). Handbook of

Implicit Social Cognition: Measurement, Theory, and

Applications. Guilford Press.

Ghahramanlou-Holloway, M., Lee-Tauler, S. Y., LaCroix,

J. M., Kauten, R., Perera, K., Chen, R., Weaver, J., &

Soumoff, A. (2018). Dysfunctional personality disorder

beliefs and lifetime suicide attempts among

psychiatrically hospitalized military personnel.

Comprehensive Psychiatry, 82, 108–114.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.01.010

Giner, L., Blasco-Fontecilla, H., Mercedes Perez-

Rodriguez, M., Garcia-Nieto, R., Giner, J., Guija, J. A.,

Rico, A., Barrero, E., Luna, M. A., de Leon, J.,

Oquendo, M. A., & Baca-Garcia, E. (2013). Personality

disorders and health problems distinguish suicide

attempters from completers in a direct comparison.

Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(2), 474–483.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.029

Goldberg, A. (1973). Psychotherapy of narcissistic injuries.

Archives of General Psychiatry, 28(5), 722–726.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1973.0175035009001

6

Gore, W. L., & Widiger, T. A. (2016). Fluctuation between

grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Personality

Disorders, 7(4), 363–371.

https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000181

Heisel, M. J., Links, P. S., Conn, D., van Reekum, R., &

Flett, G. L. (2007). Narcissistic Personality and

Vulnerability to Late-Life Suicidality. The American

Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(9), 734–741.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JGP.0000260853.63533.7d

Jaksic, N., Marcinko, D., Skocic Hanzek, M., Rebernjak,

B., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2017). Experience of Shame

Mediates the Relationship Between Pathological

Narcissism and Suicidal Ideation in Psychiatric

Outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(12),

1670–1681. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22472

Jang, J.-M., Park, J.-I., Oh, K.-Y., Lee, K.-H., Kim, M. S.,

Yoon, M.-S., Ko, S.-H., Cho, H.-C., & Chung, Y.-C.

(2014). Predictors of suicidal ideation in a community

sample: Roles of anger, self-esteem, and depression.

Psychiatry Research, 216(1), 74–81.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.054

Kealy, D., Laverdière, O., & Pincus, A. L. (2020).

Pathological Narcissism and Symptoms of Major

Depressive Disorder Among Psychiatric Outpatients:

The Mediating Role of Impaired Emotional Processing.

The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 208(2),

161–164.

https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001114

Kernis, M., & Goldman, B. (2006). Assessing stability of

self-esteem and contingent self-esteem (pp. 77–85).

Krizan, Z., & Johar, O. (2015). Narcissistic rage revisited.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(5),

784–801. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000013

L, S. (2016, September). Narcissistic personality disorder

and suicide. Psychiatria Danubina; Psychiatr Danub.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27658843/

ICE-TES 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Technology, Engineering, and Science

262

Lewitzka, U., Spirling, S., Ritter, D., Smolka, M., Goodday,

S., Bauer, M., Felber, W., & Bschor, T. (2017). Suicidal

Ideation vs. Suicide Attempts: Clinical and

Psychosocial Profile Differences Among Depressed

Patients: A Study on Personality Traits,

Psychopathological Variables, and Sociodemographic

Factors in 228 Patients. The Journal of Nervous and

Mental Disease, 205(5), 361–371.

https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000667

Links, P. S. (2013). Pathological Narcissism and the Risk

of Suicide. In Understanding and Treating

Pathological Narcissism (1st ed., pp. 167–182).

American Psychological Association.

Loeffler, L. A. K., Huebben, A. K., Radke, S., Habel, U., &

Derntl, B. (2020). The Association Between

Vulnerable/Grandiose Narcissism and Emotion

Regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 519330.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.519330

Marčinko, D., Jakšić, N., Ivezić, E., Skočić, M., Surányi,

Z., Lončar, M., Franić, T., & Jakovljević, M. (2014).

Pathological narcissism and depressive symptoms in

psychiatric outpatients: Mediating role of dysfunctional

attitudes. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 341–

352. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22033

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W.

K. (2017). Controversies in Narcissism. Annual Review

of Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 291–315.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-

045244

Millon, T. (2016). What Is a Personality Disorder? Journal

of Personality Disorders, 30(3), 289–306.

https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2016.30.3.289

Millon, T., Millon, C. M., Meagher, S. E., Grossman, S. D.,

& Ramnath, R. (2004). Personality Disorders in

Modern Life (2nd edition). Wiley.

O’Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated

motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B:

Biological Sciences, 373(1754).

https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

Pincus, A. L., Cain, N. M., & Wright, A. G. C. (2014).

Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability in

psychotherapy. Personality Disorders, 5(4), 439–443.

https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000031

Pincus, A. L., & Lukowitsky, M. R. (2010). Pathological

narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annual

Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 421–446.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.13121

5

Pompili, M., Ruberto, A., Girardi, P., & Tatarelli, R.

(2004). Suicidality in DSM IV cluster B personality

disorders. An overview. Annali Dell’Istituto Superiore

Di Sanita

, 40(4), 475–483.

Rasmussen, M. L., Dyregrov, K., Haavind, H., Leenaars, A.

A., & Dieserud, G. (2018). The Role of Self-Esteem in

Suicides Among Young Men. Omega, 77(3), 217–239.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815601514

Ren, Y., You, J., Lin, M.-P., & Xu, S. (2019). Low self-

esteem, entrapment, and reason for living: A moderated

mediation model of suicidal ideation. International

Journal of Psychology: Journal International De

Psychologie, 54(6), 807–815.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12532

Ritter, K., Vater, A., Rüsch, N., Schröder-Abé, M., Schütz,

A., Fydrich, T., Lammers, C.-H., & Roepke, S. (2014).

Shame in patients with narcissistic personality disorder.

Psychiatry Research, 215(2), 429–437.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.11.019

Robinson, A., Stasik-O’Brien, S., & Calamia, M. (2020).

Toward a More Perfect Conceptualization of

Perfectionism: An Exploratory Factor Analysis in

Undergraduate College Students. Assessment,

1073191120976859.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120976859

Roche, M. J., Pincus, A. L., Lukowitsky, M. R., Ménard, K.

S., & Conroy, D. E. (2013). An integrative approach to

the assessment of narcissism. Journal of Personality

Assessment, 95(3), 237–248.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.770400

Ronningstam, E. (2009). Narcissistic personality disorder:

Facing DSM-V. Psychiatric Annals, 39(3), 111–121.

https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20090301-09

Ronningstam, E. (2017). Intersect between self-esteem and

emotion regulation in narcissistic personality

disorder—Implications for alliance building and

treatment. Borderline Personality Disorder and

Emotion Dysregulation, 4, 3.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-017-0054-8

Ronningstam, E., & Weinberg, I. (2013). Narcissistic

Personality Disorder: Progress in Recognition and

Treatment. Focus: The Journal of Life-Long Learning

in Psychiatry, 11, 167–177.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.11.2.167

Ronningstam, E., Weinberg, I., Goldblatt, M., Schechter,

M., & Herbstman, B. (2018). Suicide and self-

regulation in narcissistic personality disorder.

Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 46(4), 491–510.

https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2018.46.4.491

Ronningstam, E., Weinberg, I., & Maltsberger, J. T. (2008).

Eleven deaths of Mr. K.: Contributing factors to suicide

in narcissistic personalities. Psychiatry, 71(2), 169–

182. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2008.71.2.169

Rosenberg, M. (2015).

Society and the Adolescent Self-

Image. Princeton University Press.

Schuck, A., Calati, R., Barzilay, S., Bloch-Elkouby, S., &

Galynker, I. (2019). Suicide Crisis Syndrome: A review

of supporting evidence for a new suicide-specific

diagnosis. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 37(3), 223–

239. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2397

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Chen, S., Saklofske, D. H.,

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2016). Perfectionism and

narcissism: A meta-analytic review. Journal of

Research in Personality, 64, 90–101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.012

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Chen, S., Saklofske, D. H.,

Mushquash, C., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2018). The

perniciousness of perfectionism: A meta-analytic

review of the perfectionism-suicide relationship.

Journal of Personality, 86(3), 522–542.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12333

Suicide and Narcissistic Personality Traits: A Review of Emerging Studies

263

Stone, M. H. (1989). Long-term follow-up of

narcissistic/borderline patients. The Psychiatric Clinics

of North America, 12(3), 621–641.

Strauman, T. J. (2017). Self-Regulation and

Psychopathology: Toward an Integrative Translational

Research Paradigm. Annual Review of Clinical

Psychology, 13, 497–523.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-

045012

Vater, A., Ritter, K., Schröder-Abé, M., Schütz, A.,

Lammers, C.-H., Bosson, J. K., & Roepke, S. (2013).

When grandiosity and vulnerability collide: Implicit

and explicit self-esteem in patients with narcissistic

personality disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and

Experimental Psychiatry, 44(1), 37–47.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.07.001

World Health Organization. (2014). WHO | Preventing

suicide: A global imperative. WHO; World Health

Organization.

http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-

prevention/world_report_2014/en/

World Health Organization. (2019, September 2). Suicide.

World Health Organization.

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-

sheets/detail/suicide

Zajenkowski, M., Maciantowicz, O., Szymaniak, K., &

Urban, P. (2018). Vulnerable and Grandiose Narcissism

Are Differentially Associated With Ability and Trait

Emotional Intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 9.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01606

Zeigler-Hill, V. (2006). Discrepancies between implicit and

explicit self-esteem: Implications for narcissism and

self-esteem instability. Journal of Personality, 74(1),

119–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-

6494.2005.00371.x

Zeigler-Hill, V., & Besser, A. (2013). A glimpse behind the

mask: Facets of narcissism and feelings of self-worth.

Journal of Personality Assessment, 95(3), 249–260.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.717150

ICE-TES 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Technology, Engineering, and Science

264