How do Indonesians Perceive Marriage? Semantics Analysis of

Marriage as a Concept and Its Relation with the Well-being

Afifah Zulinda Sari

a

, Destie Nurainy Ramadhan

b*

, Minerva Patricia

c

,

Pingkan Cynthia Belinda Rumondor

d

and Farah Mutiasari Djalal

e

Department of Psychology, Bina Nusantara University, Kemanggisan Ilir 3/45 Palmerah, Jakarta, 11480 Indonesia

Keywords: Marriage, Concept, Semantics, Well-being, Relationship Satisfaction.

Abstract: In Indonesia, being married is considered a desirable social status and associated with well-being. However,

there is a lack of research on marriage as a concept in Indonesia’s context. This study aims to explain how

Indonesians perceive marriage and how it differs from Western cultures. A total of 388 Indonesian adults

generated the meaning of marriage using a feature generation task (i.e., What is marriage according to you?).

Their well-being levels (happiness, satisfaction with life and with relationship) and demographics were also

collected to see whether a marriage was perceived differently based on these data. Descriptive analysis was

employed. The generated features were coded, counted, and classified based on participants’ well-being levels

in the three scales (happiness, life satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction). In general, marriage was

perceived uniformly and primarily as ‘the union of two parties, along with ‘involves commitment’, ‘is a state

and religion legal bond’, and ‘involves love’, regardless of their well-being levels. In other words, the

marriage concept has no association with the level of well-being. The generated features also shown a

significant overlapping with the marriage definition by Indonesian law. Theoretical implications and

comparable results from the previous (Western) studies of relationships are described in detail.

1 INTRODUCTION

In Indonesia, the construction of marriage is quite

distinctive because nuptial behavior (i.e., age at the

first marriage, post marriage residence) is highly

associated with cultural norms, also known as ‘adat’

(Buttenheim & Nobles, 2009). Moreover, amidst

modernization and shifting gender norms, the neo-

traditional idea of men as the breadwinner and

women as secondary earners (i.e., women can work

and do maternal roles) is wildly prevalent (Utomo,

2012). Traditional gender roles are also encouraged

by the 1974 Marriage Law that states that husbands

are the heads of families and that wives are

housewives (Indonesia, 1974). The idea of women as

housewives is related to ‘kodrat’ that is reinforced by

religious interpretation (Utomo, 2012). Related to

traditions, marriage for Indonesian (i.e., Bugis-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8387-7665

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3669-6807

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3166-3109

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0778-929X

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2767-8279

Makassar) involves joining individuals and two

families (Aisyah & Parker, 2014).

Marriage in Indonesia is also unique because

marriage seems to be considered a norm and higher

social status. Marital status is one of the information

stated on every Indonesians’ identity card (Kartu

Tanda Penduduk / KTP). If one has a legal partner,

then the status is displayed as ‘married’. However, the

word chosen to describe single people is ‘not yet

married’ (Belum menikah) instead of ‘single’. This

status suggests that people have to get married at

some point in their life (Kusmanto, 2016).

Moreover, “being married” is considered a higher

social status compared to “unmarried”, as implied in

the linguistic metaphor “rotten bachelor” (bujang

lapuk) and “unsold” (tidak laku) used to describe

unmarried individuals. Thus, marriage in Indonesia’s

culture is considered a momentous event that is

10

Sari, A., Ramadhan, D., Patricia, M., Rumondor, P. and Djalal, F.

How do Indonesians Perceive Marriage? Semantics Analysis of Marriage as a Concept and Its Relation with the Well-being.

DOI: 10.5220/0010742500003112

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences (ICE-HUMS 2021), pages 10-18

ISBN: 978-989-758-604-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

compulsory (Himawan et al., 2018). Despite the

importance of marriage, there is a scarce resource of

scientific findings in the psycho-linguistic field that

explains the concept of marriage as perceived by

Indonesians.

Western culture perceived marriage somewhat

differently. As opposed to an essential and socially

desirable status, marriage in Western culture is

considered a personal choice and not a societal

expectation or demand. Moreover, the goal of

marriage in Western culture (i.e., USA) has evolved

from the fulfillment of basic needs, security, status,

and love to the realization of self-actualization

(Finkel et al., 2015). Culture is not the only

determinant of the variation in the concept of

marriage. As suggested in many concept studies,

different word use depends on the spoken language

and the speaker’s age (White et al., 2018).

Semantically, marriage can be interpreted as a status,

an institution, or a social object (Roversi et al., 2013).

Moreover, marriage can also be perceived differently

based on different religions (Zarean & Barzegar,

2016).

Despite the different meanings of marriage,

research related to marriage is commonly conducted

in Western culture. Studies conducted in Western

culture (i.e., Europe and Northern America) found

that although marriage is not considered a

requirement for social acceptance and advancement,

most people get married and wish their marriages to

be satisfying and long-lasting (Karney & Bradbury,

2020). Therefore, the focus of research about

marriage in Western culture for the past ten years

revolves around satisfaction and stability in marriage.

Although the concept of marriage has a different

meaning than the concept of relationship (i.e., not all

people who have a relationship are married), these

two words are often used interchangeably in Western

scientific articles. One example of a frequently used

marital satisfaction measure is using the Couple

Satisfaction Index (CSI; Funk & Rogge, 2007).

Moreover, relationship satisfaction serves as a

foundation to understand how a relationship and

marriage works, based on the degree of happiness of

the relationship, sense of connection with a partner,

needs fulfillment by partner, and feelings about the

relationship (Funk & Rogge, 2007). Thus, it is

implied that the prominent aspect of marriage in the

Western perspective is the relationship of two

individuals (i.e., husband and wife).

Previous studies used relationship satisfaction as

an indicator of marital satisfaction and found that

married individuals are happier and more satisfied

with their life compare to those unmarried people

(Gove et al., 1990; Mastekaasa, 1994; Stack &

Eshleman, 1998; Verbakel, 2012, in Mikucka, 2016).

In contrast, lower marital satisfaction leads to

cheating and divorce (Fincham & May 2017;

Hirschberger et al., 2009; Karney & Bradbury, 1995).

In Western culture, happiness is considered the

ultimate goal, both at the individual and societal

levels (Veenhoven, 1994, in Lyubomirsky & Lepper,

1999). Moreover, marital satisfaction can

significantly increase life satisfaction (Grover &

Helliwell, 2019), a cognitive-judgmental process that

depends on comparing one’s condition and their

desired standard (Diener et al., 1985). It can be

implied that in Western culture, a satisfying

relationship between husband and wife (i.e., needs are

met by partner, the relationship is perceived as happy

and rewarding, more positive feelings toward the

relationship) is associated with individual’s

happiness, life satisfaction, and marital stability.

In Indonesia, marriage also expected to be happy

and eternal, as described in Marital Law no. 1, 1947:

“Marriage is a physical and spiritual union of a man

and woman as husband and wife whose goal is to

form a happy and eternal family (household), based

on The One and only God” (Indonesia, 1974).

However, the definition of marriage derived from

Marital Law (legal definition) also implied that

marriage revolves around two individuals and is

related to spirituality and religion. Moreover, in

reality, some individuals choose to be in a marital

union despite feeling miserable and experiencing

violence from the partner (Segaf et al., 2009).

Experiencing violence contradicts the goal of

marriage in Marital Law and findings in Western

Culture that low marital satisfaction will lead to

divorce. It is possible that Indonesia’s unique culture

laid a foundation for a different meaning of marriage.

Marital satisfaction leads to happiness and life

satisfaction. However, these conclusions are drawn

from research conducted in Western culture. On the

other hand, Indonesian perceived marriage

differently. Therefore, this study aims to describe

how Indonesian people perceived marriage as a

concept. Moreover, this research also explores the

concept of marriage based on levels of well-being

(i.e., happiness, life satisfaction, and relationship

satisfaction) and congruence with the formal

definition of marriage based on the law (Sekretariat

Negara Republik Indonesia 1974). In other words:

How do Indonesian perceive the concept of marriage?

Do people with different levels of well-being and

demographics perceive the concept of marriage

differently? Does Indonesian’s perception of

How do Indonesians Perceive Marriage? Semantics Analysis of Marriage as a Concept and Its Relation with the Well-being

11

marriage as a concept congruent with the legal

definition of marriage?

2 METHODS

2.1 Ethics Statement

This study was conducted with the approval of the

Research Ethics Committee of the Department of

Psychology, University of Bina Nusantara. Written

informed consent was obtained from all participants

before starting the task. This study was also pre-

registered before the data collection on September

15

th

, 2020 (see https://osf.io/fhyq2).

2.2 Participants

A total of 393 (311 females, 76 males, and 1 indicated

the gender as ‘others’, M

age

= 25.61, SD

age

= 9.27) adult

participants participated in this study. Five of the

participants were domiciled abroad and were

excluded from the analysis to control the cultural

biases. Thus, 388 participants were included in the

analysis. They were all Indonesians who were at least

18 years old. Based on Erikson and Levinson’s

developmental theory model, when a person reaches

an early adulthood stage (18 years old onwards), they

develop personal identity feelings and a need to be

close to other people. Therefore, finding and

developing an intimate relationship with a partner

becomes a priority for people in this age group

(Hewstone et al., 2005). All participants did the study

voluntarily and received no compensation for their

participation.

2.3 Materials

The material was comprised of four different parts:

feature generation task, Couple Satisfaction Index

(CSI), Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), and

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SwLS).

A feature generation task was employed to look at

the features people give towards five different

abstract concepts (i.e., Happiness, Marriage, Family,

Loyalty, and Love). Participants were asked to

answer: “What is a marriage according to you?” and

expected to list a maximum of 15 features that

describes each concept. However, only the responses

for the concept “Marriage” were discussed in this

present study.

A Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), taken from

Lyubomirsky and Lepper (1997), was used to

measure the level of happiness. This questionnaire

consists of four items in which participants were

asked to rate their answers on a 6-point rating scale.

Each item had a different endpoint, ranging from a

negative response such as ‘very unhappy’ or ‘not at

all to a positive response, such as ‘very happy’ or ’a

great deal’. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the

translated version of SHS was 0.64.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SwLS; Diener et

al., 1985) was employed to measure how to satisfy a

person with their life. This scale comprised five items

in which participants should specify their level of

agreement to disagreement from a scale ranging from

1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The

reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha

reliability coefficient, and the results revealed 0.76.

The couple satisfaction index (CSI; Funk &

Rogge, 2007) comprises 34 items in which

participants were asked to rate each statement on a

different scale, ranging from 1 to 6 or 7, depending

on the question group. Using Cronbach’s alpha

reliability coefficient, a score of 0.98 was obtained.

All the materials were translated into Indonesian.

The higher the scores in the well-being measurements

(CSI, SHS, SwLS) indicates the higher the level of

happiness or satisfaction.

2.4 Procedures

All participants were given an online survey link. The

survey was administered using the Google Form

platform. Participants began by indicating their

agreement to participate by filling in informed

consent. They were then continued to the feature

generation task. Before they fill in the well-being

surveys (i.e., SHS, SwLS, and CSI), participants were

asked to complete a set of demographic questions.

Their answer on the relationship status determined

whether they have to complete the CSI or not. If they

were in a relationship, participants were asked to

complete all three well-being surveys. Otherwise,

they only needed to complete SHS and SwLS. All

instructions and questions were written in Indonesian.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Indonesian’s Perception of the

Concept of Marriage: Top 10

Features

A total of 2.116 generated features for the concept

‘Marriage’ were first processed using McRae, De Sa,

and Seidenberg’s (1997) procedure. First, features

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

12

that give the same meaning or synonym (i.e., the

union of two hearts and the union of two families)

were given an identical label (e.g., the union of two

parties). Then, features that provide different

information (i.e., the union of two parties and

building a family) were split and treated as separate

features (i.e., the union of two parties and to build a

family). This procedure yielded 147 different features

(i.e., the numbers of types and not tokens).

Each feature was then calculated for the

frequency, how often participants generated them.

The frequency for each feature was ranging from 1 to

168. Table 1 below shows the ten most generated

features for the concept ‘Marriage’.

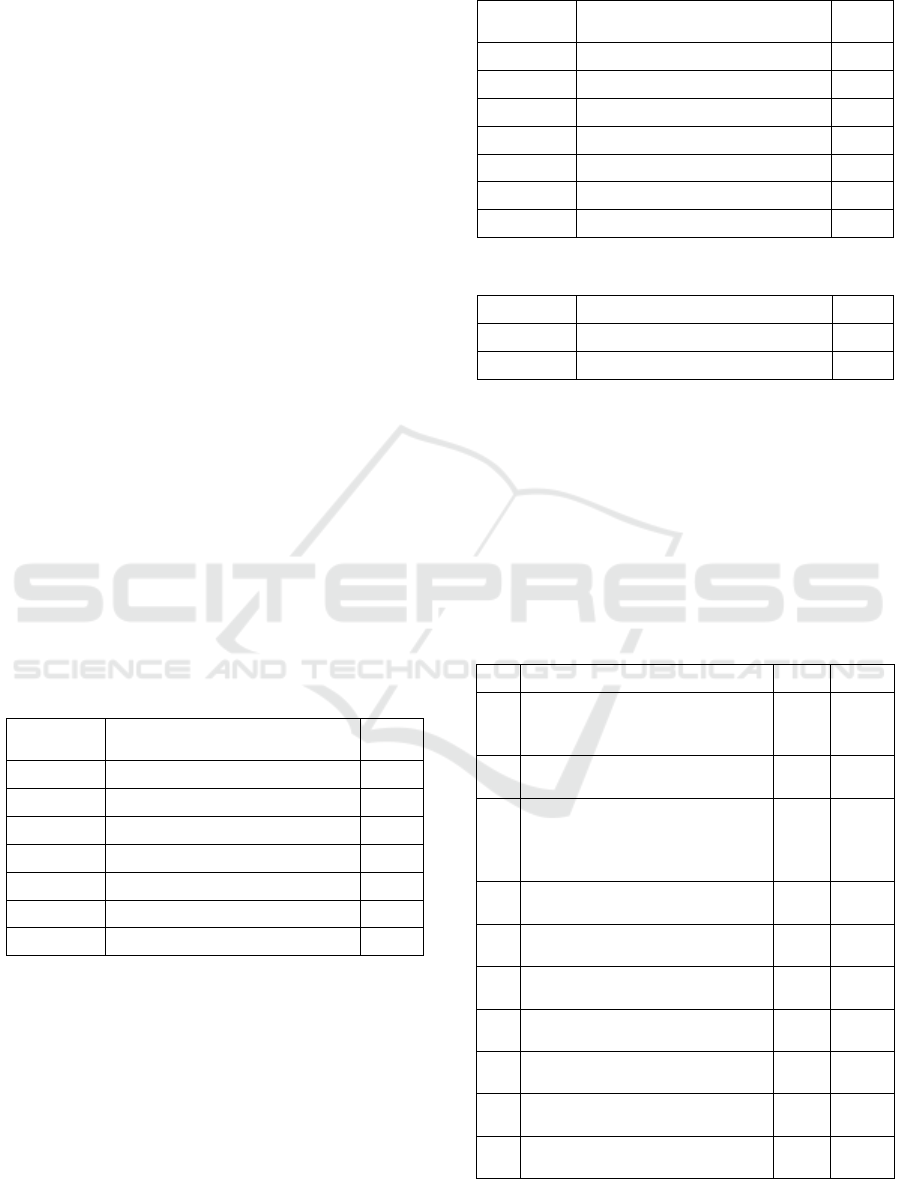

Table 1: The ten most generated features.

No Features N %

1

The union of two parties

Hubungan dua pihak yang menyatu

168 7.94%

2

It involves commitment

M

elibatkan komitmen

153 7.23%

3

A legal bond according to law and

religion

Suatu ikatan yang sah secara

hukum dan a

g

ama

138 6.52%

4

It involves love

M

elibatkan cinta

119 5.62%

5

It involves agreements

A

da perjanjian

98 4.63%

6

Is sacred

B

ersi

f

at sakral

89 4.21%

7

To build a family

Untuk membentuk keluar

g

a

80 3.78%

8

To live as a couple

Hidup bersama pasangan

79 3.73%

9

Is an observance

Suatu ibadah

65 3.07%

10

To procreate

Untuk memiliki keturunan

59 2.79%

Based on the top 3 most generated features,

participants in this study seems to portray the

definition of marriage derived from Marital Law no

1, 1947 (legal definition). Marriage is perceived as a

union of two parties (individuals as well as families),

involves commitment and a legal bond according to

law and religion. Interestingly, in a collective culture

like Indonesia, marriage is a personal decision and a

family matter (Aisyah & Parker, 2014). Moreover,

marriage is perceived as both a union and also

institution. This finding complements Kusmanto’s

(2016) observation that marriage is considered

necessary because it is a normative union supported

by nation (law) and sanctified by religion.

Another interesting finding is that features related

to religion and spirituality are mentioned three times

in the top ten features: a legal bond according to law

and religion, sacred, and observance. Participants of

this study seem to associate marriage as an expression

of conforming to society’s rules and submitting to

divine principles. This finding might be related to the

first principle (or sila) on Indonesia’s state foundation

(Pancasila), which is a belief in one Supreme Being;

thus, Indonesia is not a secular country, and this

statement encompasses a wide variety of religions,

including Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, and

Buddhism (Morfit, 1981). Additionally, spirituality

plays an essential role in people’s lives living in

Indonesia (Roosseno, 2015), and it affects

Indonesian’s perception of marriage as a concept.

Compared to other countries, most Indonesian

(96%) agree that belief in God is necessary to be

moral and have good values (Tamir, Connaughton, &

Salazar, 2020). Thus, participants in Indonesia seem

to be more ‘religious ‘compare to other countries

(median = 45% agree that it is necessary to believe in

God to be moral and have good values). In

comparison, only 9% of the participant in Sweden,

20% in the UK, and 44% in the USA who say belief

in God is necessary to be moral and have good values

(Tamir et al., 2020).

In addition to belief in God, Indonesia’s culture

can also explain the salient religious and normative

sense in Indonesian’s perception of the concept of

marriage. Indonesia has a high score in collectivism,

which means that transgression of norms leads to

shame feelings (Hofstede, 2011). As most people in

Indonesia are Muslims and they endorsed marriage as

sacred and as an observance, the majority of people

in Indonesia perceived marriage as such. Moreover, a

high score in collectivism also explains why the most

generated feature is “the union of two parties”.

Another indicator of high collectivism is that opinions

and votes are predetermined by the in-group

(Hofstede, 2011). Thus, marriage is not only about

two individuals. An individual’s decision to marry is

highly affected by parents (Utomo, 2015).

This finding is in line with a previous study that

found that marital behaviors are shaped not only by

cultural norms but also by religious interpretation

(Buttenheim & Nobles, 2009; Utomo, 2012).

Marriage is perceived as a prerequisite to build a

family and procreate, as implied in Muslim’s spiritual

belief. Consequently, sexual activity is regarded as a

means to procreate and needs to be conducted within

marital union. Therefore, premarital sex is prohibited

by religion in Indonesia. Moreover, for some young

adults, premarital sex is perceived as adultery or zina

How do Indonesians Perceive Marriage? Semantics Analysis of Marriage as a Concept and Its Relation with the Well-being

13

(Bennett, 2007), and getting married can be a solution

to prevent adultery. In contrast, in Western culture,

premarital sex is considered normal.

Nevertheless, a more personal and affective

characteristic of marriage comes later in the fourth

and eighth most frequent features: ‘it involves love’

and ‘to live as a couple’. These features are similar to

the Western concept of marital satisfaction: focusing

on feelings towards the relationship and one’s partner

(Funk & Rogge, 2007). Thus, Indonesian might have

a shared meaning of marriage with their Western

counterparts. However, this characteristic of marriage

occurs less than normative and sacred features of

marriage as perceived by Indonesian. It is expected

because the way a concept is perceived (cognition)

depends on the context in which a relationship is

situated (McNulty, 2016).

3.2 The Top Features based on the

Well-being Levels

To know whether participants who have different

levels of well-being produced various kinds of

features, their level of happiness, life satisfaction, and

relationship satisfaction were calculated. The average

scores for each participant were calculated for the

three well-being scales and grouped based on each

scale norm. Tables 2, 3, and 4 showed the level of

classification of each scale and the number of

participants in each level.

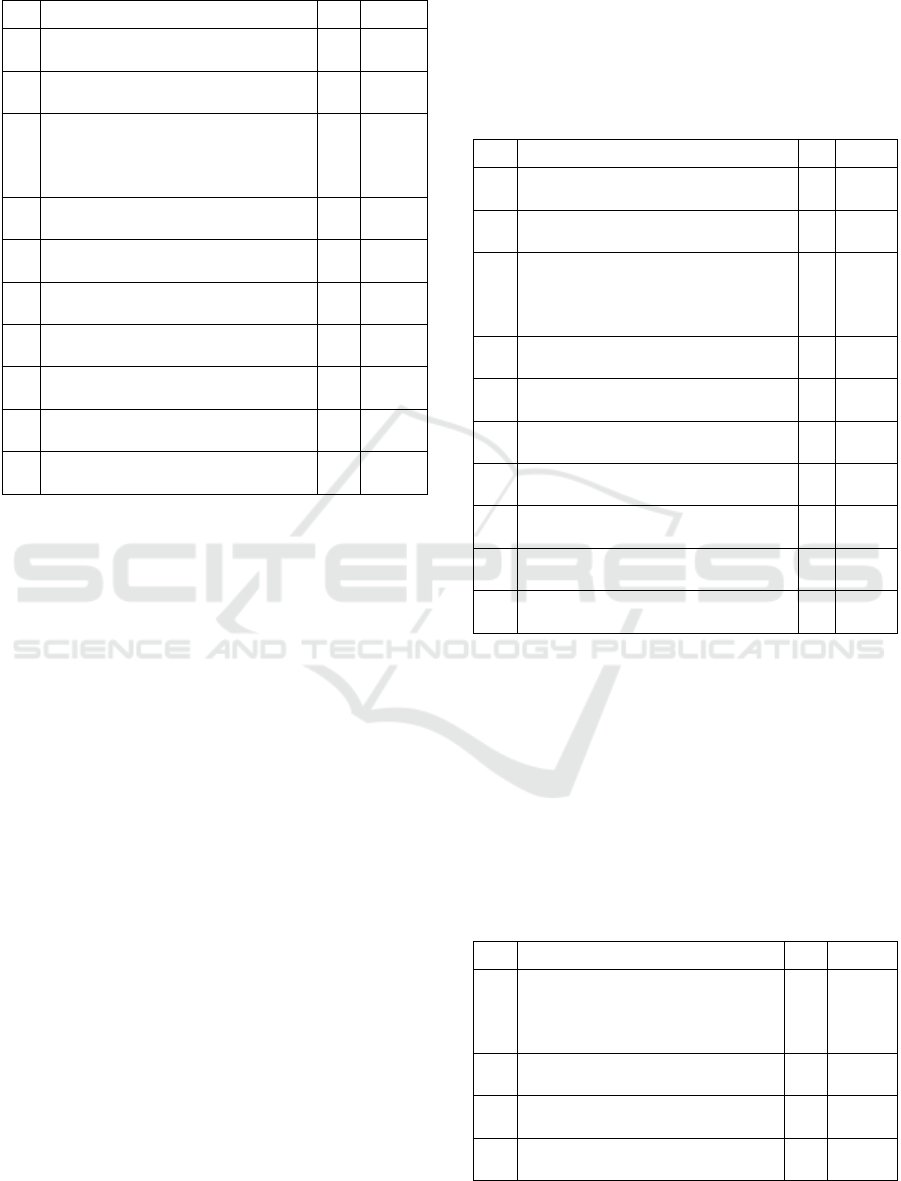

Table 2: The classification of subjective happiness.

Average

Score

SHS N

6.1 – 7.0

Extremely happy 39

5.1 – 6.0

Happy 141

4.1 – 5.0

Slightly happy 129

4.0

Neutral 24

3.1 – 3.9

Slightly happy 40

2.1 – 2.9

Unhappy 14

1.0 – 2.0

Extremely unhappy 1

All the generated features were grouped based on

participants’ scores on each scale. For the sake of

simplicity, we presented the top ten generated

features based on two levels of classification (i.e.,

Happy-Unhappy and Satisfied-Dissatisfied) with the

following rule: in SHS and SwLS, people scored

above 4.0 or categorized as slightly happy/satisfied,

happy/satisfied, and extremely happy/satisfied, were

grouped into one category, ‘Happy’ in SHS scale and

‘Satisfied’ in SwLS.

Table 3: The classification of satisfaction with life.

Average

Score

SwLS N

6.1 – 7.0

Extremely satisfied 48

5.1 – 6.0

Satisfied 106

4.1 – 5.0

Slightly satisfied 114

4.0

Neutral 20

3.1 – 3.9

Slightly dissatisfied 74

2.1 – 2.9

Dissatisfied 19

1.0 – 2.0

Extremely dissatisfied 7

Table 4: The classification of relationship satisfaction.

Total Score

CSI N

≥ 105

Satisfied 122

≤ 104

Dissatisfied 38

The top 10 generated features produced by the

‘Happy’ participants were listed in Table 5, and the

top ten features generated by the ‘Satisfied’ people

were shown in Table 6. Whereas those who scored

lower than 4.0 (i.e., slightly unhappy/dissatisfied,

unhappy/dissatisfied, and extremely unhappy/

dissatisfied on SHS and SwLS scales were grouped

as ‘Unhappy’ and ‘Dissatisfied’.

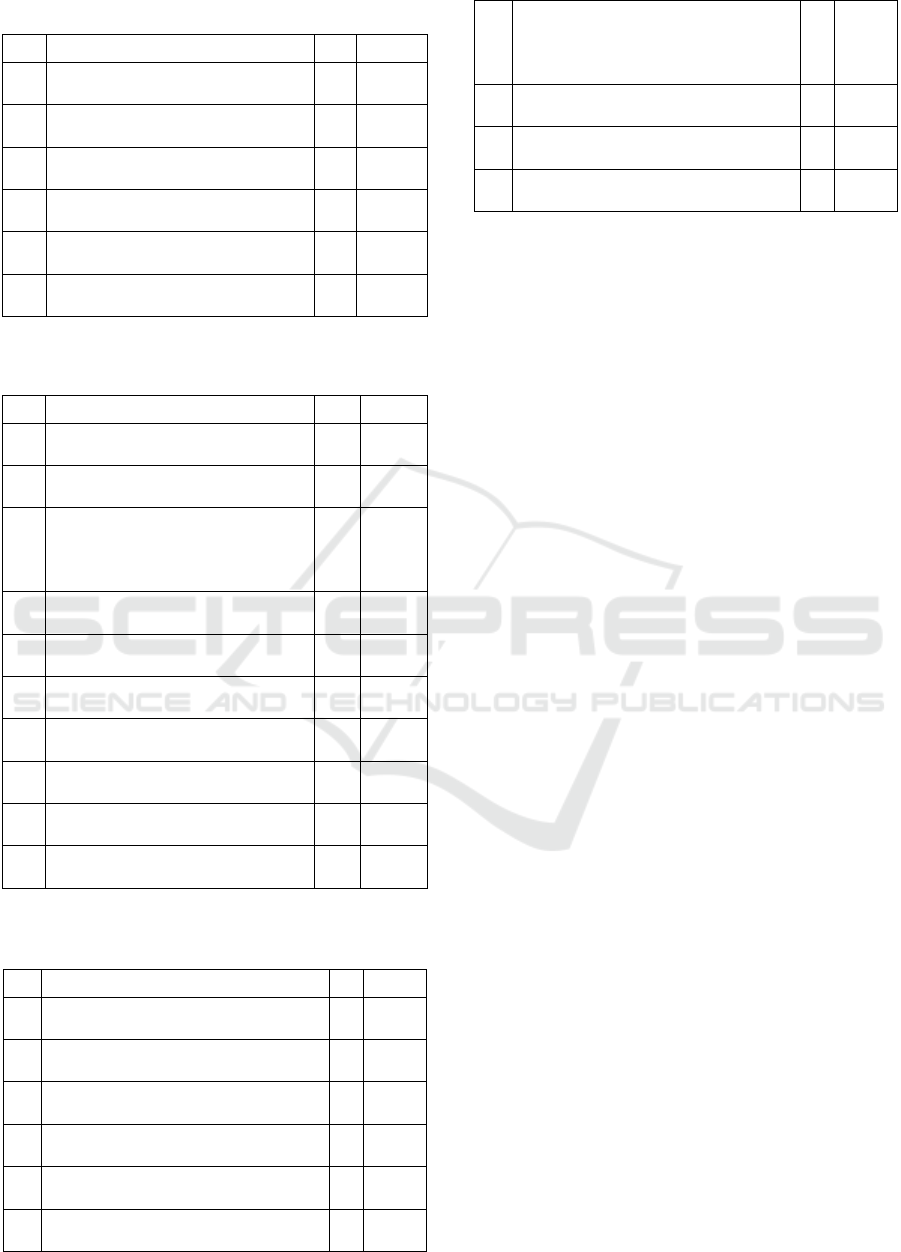

Table 5: The ten most generated features produced by the

‘Happy’ participants who scored above 4.0 on SHS.

No Features N %

1

The union of two parties

Hubungan dua pihak yang

men

y

atu

138 8.23%

2

It involves commitment

M

elibatkan komitmen

129 7.69%

3

A legal bond according to law

and religion

Suatu ikatan yang sah secara

hukum dan agama

102 6.08%

4

It involves love

M

elibatkan cinta

96 5.72%

5

It involves agreements

A

da

p

er

j

an

j

ian

84 5.01%

6

Is sacred

B

ersifat sakral

70 4.17%

7

To build a family

Untuk membentuk keluar

g

a

64 3.82%

8

To live as a couple

Hidu

p

bersama

p

asan

g

an

62 3.70%

9

Is an observance

Suatu ibadah

53 3.16%

10

A reciprocal relationship

A

da hubungan timbal bali

k

51 3.04%

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

14

Table 6: The ten most generated features produced by the

‘Satisfied’ participants who scored above 4.0 on SwLS.

No Features N %

1

The union of two parties

Hubungan dua pihak yang menyatu

121 8.10%

2

It involves commitment

M

elibatkan komitmen

107 7.17%

3

A legal bond according to law and

religion

Suatu ikatan yang sah secara hukum

dan agama

92 6.16%

4

It involves love

M

elibatkan cinta

87 5.83%

5

It involves agreements

A

da

p

er

j

an

j

ian

72 4.82%

6

Is sacred

B

ersi

f

at sakral

61 4.09%

7

To live as a couple

Hidup bersama pasangan

54 3.62%

8

To build a family

Untuk membentuk keluar

g

a

50 3.35%

9

A reciprocal relationship

A

da hubun

g

an timbal bali

k

47 3.15%

10

Is an observance

Suatu ibadah

46 3.08%

In Table 7, the top 10 generated features from

participants classified as satisfied in their CSI will be

shown. Table 8 showed the most generated features

by the Unhappy participants, and Table 9 showed the

top ten features from the Dissatisfied.

As shown in Table 5, Table 6, and Table 7, the

composition of the ten most generated features from

all groups of participants who scored high on SHS,

SwLS, and CSI was nearly identical, only the order of

the feature was slightly different. Further, all groups

seemed to agree that marriage is the union of two

people. Moreover, the top five features in happy and

satisfied participants echo the top five features in the

overall sample. Interestingly, two new features

emerged in the satisfied and happy group: ’a

reciprocal relationship’ (observed in participants who

are happy and satisfied with life) and ‘it involves

responsibilities’ (observed in participants who are

satisfied with their current relationship.

‘A reciprocal relationship’ implies a process with

a sense of ‘we-ness’ rather than characteristic of

marriage. The perception that marriage is teamwork

rather than individual work is similar to communal

coping; a process entails appraising a stressor as

“our” problem and taking steps as a couple to improve

the issue (Borelli et al., 2013). Communal orientation

promotes individual and relational well-being (Le et

al., 2013). Whereas ‘it involves responsibility’

implies a realistic perception of marriage and

describes motivation to maintain the marriage, thus

increase moral commitment (Johnson et al., 1999).

This result implies that happy and satisfied

participants have a combination of normative,

affective, and realistic perceptions of marriage.

Table 7: The ten most generated features produced from the

‘Satisfied’ participants on CSI.

No Features N %

1

The union of two parties

Hubun

g

an dua

p

ihak

y

an

g

men

y

atu

60 7,59%

2

It involves commitment

M

elibatkan komitmen

56 7,09%

3

A legal bond according to law and

religion

Suatu ikatan yang sah secara hukum

dan agama

44 5,57%

4

It involves love

M

elibatkan cinta

43 5,44%

5

It involves agreements

A

da

p

er

j

an

j

ian

38 4,81%

6

To live as a couple

Hidup bersama pasangan

31 3,92%

7

To build a family

Untuk membentuk keluar

g

a

28 3,54%

8

Is sacred

B

ersi

f

at sakral

28 3,54%

9

It involves responsibilities

A

da tanggung jawab

24 3,04%

10

Is an observance

Suatu ibadah

22 2,78%

As can be seen in Tables 8, 9, and 10, the

compositions of the features generated by the

unhappy and dissatisfied participants were quite

similar. However, compared with the happy and

satisfied participants, new features emerged as the

most generated ones. Features such as ‘there are

consequences, it involves happiness, and it involves

responsibilities’ were rather popular among these

groups.

Table 8: The ten most generated features produced by the

‘Unhappy’ participants scored lower than 4.0 on SHS.

No Features N %

1

A legal bond according to law and

religion

Suatu ikatan yang sah secara

hukum dan a

g

ama

25 7,96%

2

The union of two parties

Hubungan dua pihak yang menyatu

22 7,01%

3

It involves commitment

M

elibatkan komitmen

20 6,37%

4

It involves love

M

elibatkan cinta

18 5,73%

How do Indonesians Perceive Marriage? Semantics Analysis of Marriage as a Concept and Its Relation with the Well-being

15

Table 8: (cont.).

No Features N %

5

There are consequences

A

da konsekuensi

14 4,46%

6

Is sacred

B

ersifat sakral

13 4,14%

7

To build a family

Untuk membentuk keluarga

12 3,82%

8

To live as a couple

Hidu

p

bersama

p

asan

g

an

10 3,18%

9

It involves happiness

A

da kebahagiaan

9 2,87%

10

It involves responsibilities

A

da tanggung jawab

9 2,87%

Table 9: The ten most generated features produced by the

‘Dissatisfied’ participants scored lower than 4.0 on SwLS.

No Features N %

1

The union of two parties

Hubungan dua pihak yang menyatu

40 7,45%

2

It involves commitment

M

elibatkan komitmen

37 6,89%

3

A legal bond according to law and

religion

Suatu ikatan yang sah secara

hukum dan agama

35 6,52%

4

It involves love

M

elibatkan cinta

27 5,03%

5

To build a family

Untuk membentuk keluar

g

a

26 4,84%

6

Is sacred

B

ersi

f

at sakral

22 4,10%

7

It involves agreements

A

da perjanjian

20 3,72%

8

Is an observance

Suatu ibadah

18 3,35%

9

To live as a couple

H

idu

p

bersama

p

asan

g

an

17 3,17%

10

It involves two individuals

M

elibatkan dua individu

15 2,79%

Table 10: The ten most generated features produced by

participants who classified as dissatisfied in CSI

.

No Features N %

1

It involves commitment

M

elibatkan komitmen

19 9,90%

2

Is sacred

B

ersi

f

at sakral

12 6,25%

3

It involves agreements

A

da perjanjian

11 5,73%

4

To build a family

Untuk membentuk keluarga

10 5,21%

5

The union of two people

Hubun

g

an dua

p

ihak

y

an

g

men

y

atu

10 5,21%

6

To procreate

Untuk memiliki keturunan

10 5,21%

7

A legal bond according to law and

religion

Suatu ikatan yang sah secara hukum

dan a

g

ama

9 4,69%

8

Is an observance

Suatu ibadah

8 4,17%

9

There are consequences

A

da konsekuensi

7 3,65%

10

It involves happiness

A

da kebaha

g

iaan

5 2,60%

3.3 Marriage According to the

Indonesian Governmental

Regulation

According to the Indonesian governmental

regulations (Undang-Undang Nomor 1 Tahun 1974,

pasal 1), marriage is defined as an eternal bond

between a man and a woman as husband and wife

with a purpose to build a happy family based on belief

in the Almighty God (Indonesia, 1974). Some of the

generated features in this study can be linked with this

definition. At least six features were closely related to

what the government defined as a marriage for

Indonesian. Features such as ‘A legal bond according

to law and religion’, ‘The union of two parties’, ‘To

build a family’, ‘Involves happiness’, ‘An eternal

relationship’, ‘Involves God’ represent each of the

domains specified in the definition. Those first three

features were endorsed as the top 10 generated

features, and the rest was at least in the top 40. We

also found that most participants generated at least

one feature related to the regulation, suggesting that

Indonesians perceive marriage as something

normative and sacred.

This normative perception of marriage as a

concept can be explained by the collective nature of

Indonesia’s culture. As discussed earlier, some

indicators of high collectivism are that transgression

of norms leads to shame feelings and that harmony

should always be maintained (Hofstede, 2011). Thus,

it is understandable that participants tend to give a

normative answer about marriage to avoid shame or

disturbing harmony.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study describes the concept of marriage in

Indonesia, a country in Eastern culture with a high

score in collectivist culture (Hofstede, 2011;

Mangundjaya, 2013). Participants of this study are

Indonesia’s citizens and reside in various cities in

Indonesia. This study indicates that Indonesians

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

16

provide various features of marriage in explaining

their understanding of marriage as a concept. Most of

the features are normative and related to religious

belief. However, some features imply affective (i.e.,

‘It involves love’) and realistic function of marriage

(i.e., ‘To build a family’, ‘To procreate’).

However, the result of this study indicated that the

variety of features used to describe marriage is not

associated with participant’s level of well-being

(happiness, life satisfaction, and relationship

satisfaction). Additionally, Indonesians in various

well-being levels and demographics groups agree that

marriage is the union of two people. Moreover, each

participant in this study provided at least one feature

following the formal definition of marriage described

in the law.

The limitation of this study is that several

demographic data were also obtained in this study but

were not included in the analysis, namely religion,

area of domicile, ethnicity, average monthly income,

and employment status. Therefore, we suggest that

further research can replicate this research and

analyze other demographic variables to determine

whether the variations of the concept of marriage are

associated with other demographic data. Moreover,

this study only concerns the concept of marriage in

Indonesia, with high collectivism cultural dimension.

Thus, future research can be conducted cross-

culturally. Despite the limitations, this study provides

insights into the concept of marriage in Indonesia

from a semantic perspective and its relation (or lack

thereof) to individual and relational well-being.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AZS, DNR, and MP are currently last year

undergraduate students of Psychology at Bina

Nusantara University. PCBR and FMD are lecturers

at Bina Nusantara University. All five authors

discussed the findings thoroughly, read and approved

the final version of the manuscript. All data and

materials are stored in and can be accessed on Open

Science Framework: (https://osf.io/kvhpq/?view

_only=0ca6abc17ec9419380a57e692c13a0b3).

REFERENCES

Aisyah, S., Parker, L., (2014). Problematic conjugations:

Women’s agency, marriage and domestic violence in

Indonesia. Asian Studies Review, 38(2), 205–223.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2014.899312

Bennett, L. R., (2007). Zina and the enigma of sex

education for Indonesian Muslim youth. Sex Education,

7(4), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/1468181070163

5970

Borelli, J. L., Sbarra, D. A., Randall, A. K., Snavely, J. E.,

St. John, H. K., & Ruiz, S. K., (2013). Linguistic

indicators of wives’ attachment security and communal

orientation during military deployment. Family

Process, 52(3), 535–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp

.12031

Buttenheim, A. M., Nobles, J., (2009). Ethnic diversity,

traditional norms, and marriage behaviour in Indonesia.

Population Studies, 63(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/

10.1080/00324720903137224

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S.,

(1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of

Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Fincham, F. D., May, R. W., (2017). Infidelity in romantic

relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 70–

74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.008

Finkel, E. J., Cheung, E. O., Emery, L. F., Carswell, K. L.,

& Larson, G. M., (2015). The suffocation model: why

marriage in america is becoming an all-or-nothing

institution. Current Directions in Psychological

Science, 24(3), 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/09

63721415569274

Funk, J. L., Rogge, R. D., (2007). Testing the ruler with

item response theory: increasing precision of

measurement for relationship satisfaction with the

Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family

Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/

0893-3200.21.4.572

Grover, S., Helliwell, J. F., (2019). How’s life at home?

New evidence on marriage and the set point for

happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(2), 373–

390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017

-9941-3

Hewstone, M., Fincham, F. D., & Foster, J., (2005).

Psychology, BPS Blackwell. UK, 1

st

edition.

Himawan, K. K., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S., (2018).

What does it mean to be single in Indonesia?

Religiosity, social stigma, and marital status among

never-married Indonesian adults. SAGE Open, 8(3),

215824401880313. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440

18803132

Hirschberger, G., Srivastava, S., Marsh, P., Cowan, C. P.,

& Cowan, P. A., (2009). Attachment, marital

satisfaction, and divorce during the first fifteen years of

parenthood. Personal Relationships, 16(3), 401–420.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01230.x

Hofstede, G., (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The

Hofstede model in context. online readings in

psychology and culture, 2(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/1

0.9707/2307-0919.1014

Indonesia, R. Undang-undang tentang perkawinan. , Pub.

L. No. 1, 2 (1974). Indonesia: https://peraturan.bpk

.go.id/Home/Details/47406/uu-no-1-tahun-1974

Johnson, M. P., Caughlin, J. P., & Huston, T. L., (1999).

The Tripartite nature of marital commitment: personal,

How do Indonesians Perceive Marriage? Semantics Analysis of Marriage as a Concept and Its Relation with the Well-being

17

moral, and structural reasons to stay married. Journal

of Marriage and the Family, 61(1), 160–177.

Karney, B. R., Bradbury, T. N., (1995). The longitudinal

course of marital quality and stability: A review of

theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin,

118(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1037

/0033-2909.118.1.3

Karney, B. R., Bradbury, T. N., (2020). Research on marital

satisfaction and stability in the 2010s: challenging

conventional wisdom. Journal of Marriage and Family,

82(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12635

Kusmanto, J. (2016). Exploring the cultural cognition and

the conceptual metaphor of marriage in Indonesia.

LiNGUA: Jurnal Ilmu Bahasa Dan Sastra, 11(2), 63.

https://doi.org/10.18860/ling.v11i2.3670

Le, B. M., Impett, E. A., Kogan, A., Webster, G. D., &

Cheng, C., (2013). The personal and interpersonal

rewards of communal orientation. Journal of Social and

Personal Relationships, 30(6), 694–710. https://doi.

org/10.1177/0265407512466227

Lyubomirsky, S., Lepper, H. S., (1999). A measure of

subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and

construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2),

137–155.

Mangundjaya, W. L. H., (2013). Is there cultural change in

the national cultures of Indonesia? Steering the Cultural

Dynamics, 59–68.

McNulty, J. K., (2016). Highlighting the contextual nature

of interpersonal relationships. Advances in

Experimental Social Psychology, 54, 247–315. https://

doi.org/10.1016/BS.AESP.2016.02.003

McRae, K., De Sa, V. R., & Seidenberg, M. S., (1997). On

the nature and scope of featural representations of word

meaning. Journal of Experimental Psychology:

General, 126(2), 99–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-

3445.126.2.99

Mikucka, M., (2016). The life satisfaction advantage of

being married and gender specialization. Journal of

Marriage and Family, 78(3), 759–779. https://doi.

org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12290

Morfit, M., (1981). Pancasila: The Indonesian state

ideology according to the new order government author

( s ): Michael Morfit Published by : University of

California Press Stable URL : http://www.jstor.org/

stable/2643886. Asian Survey, 21(8), 838–851.

Roosseno, T. N., (2015). Tentang manusia indonesia,

Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. Jakarta.

Roversi, C., Borghi, A. M., & Tummolini, L., (2013). A

marriage is an artefact and not a walk that we take

together: an experimental study on the categorization of

artefacts.

Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 4(3),

527–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-013-0150-7

Segaf, Z., Yumpi-R, F., & H, P. K., (2009). Memahami

alasan perempuan bertahan dalam kekerasan domestik.

Insight: Jurnal Pemikiran Dan Penelitian Psikologi,

5(1), 30–47.

Tamir, C., Connaughton, A., & Salazar, A. M., (2020). The

Global God Divide. Richard Dawkins Foundation for

Reason and Science. https://richarddawkins.net/

2020/07/the-global-god-divide/

Utomo, A. J., (2012). Women as secondary earners:

Gendered preferences on marriage and employment of

university students in modern Indonesia. Asian

Population Studies, 8(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.

1080/17441730.2012.646841

Utomo, A. J., (2015). Gender in the midst of reforms:

attitudes to work and family roles among university

students in urban Indonesia. Marriage and Family

Review, 52(5), 421–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/

01494929.2015.1113224

White, A., Storms, G., Malt, B. C., & Verheyen, S., (2018).

Mind the generation gap: Differences between young

and old in everyday lexical categories. Journal of

Memory and Language, 98(January), 12–25. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2017.09.001

Zarean, M., Barzegar, K. (2016). Marriage in Islam,

Christianity, and Judaism. Religious Inquiries, 5(9),

67–80.

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

18