Data Governance Capabilities:

Maturity Model Design with Generic Capabilities Reference Model

Jan Merkus

a

, Remko Helms

b

and Rob Kusters

c

Faculty of Management, Science & Technology, Open Universiteit, Valkenburgerweg 177, Heerlen, The Netherlands

Keywords: Data Governance, Maturity Model, Capabilities, Metaplan, Reference Model.

Abstract: To measure Data Governance, researchers designed a few Data Governance Maturity Models, but the used

capabilities are very different, resulting in different measurement outcomes. This research aims to find a

substantiated and validated set of Data Governance capabilities for Data Governance Maturity Models design.

We apply the Maturity Model design procedure model of Becker et al. for methodology, which we

complement with the Generic Capability Reference model to validate the capabilities. As results, we find a

proper set of Data Governance capabilities for designing a Data Governance Maturity Models. Furthermore,

we validate the set of DG capabilities against the GCR model, of which we conclude that the Generic

Capability Reference model is valid as a reference model for the (re)design of Maturity Models.

1 INTRODUCTION

Data Governance (DG) literature is still growing, and

it needs further research on what can be done for DG

(Abraham, Schneider, & Brocke, 2019; Lis & Otto,

2021). To learn what an organisation already does,

Governance’ status quo in an organisation can be

measured with Maturity Models (MM) (Becker,

Knackstedt, & Poeppelbuss, 2009). So, Data

Governance’ status quo can be measured with a Data

Governance Maturity Model (DGMM).

When comparing the few existing DGMMs, we

found a lack of agreement on the capabilities used.

We further notice that only a few of these existing

models have seen some empirical validation. Yet,

capabilities are the foundation of a MM and must be

selected appropriately to measure maturity

accurately. Therefore, further research is necessary

on a properly selected and validated set of DG

capabilities to design a DGMM.

To develop a more validated set of DG

capabilities, we propose using the recently published

Generic Capability Reference (GCR) model (Merkus,

Helms, & Kusters, 2020). This reference model is

based on research in which existing maturity models

have been compared to identify capabilities

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2216-7816

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3707-4201

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4069-5655

commonly used in maturity models, i.e., generic

capabilities. This research uses this model to identify

DG capabilities. Furthermore, a second objective is

testing the usability of the GCR model to support

MM development.

Therefore, the resulting research questions are

twofold:

What is a substantiated set of DG capabilities for

designing a DGMM based on literature?

To what extent is the Generic Capability

Reference (GCR) model suitable as a reference model

for designing MMs to validate the found DG

capabilities?

To research these questions we used the following

steps, which are also the steps described in the

remainder of this paper. First, conduct systematic

literature research (SLR) for DG capabilities. Then,

classify the SLR results with a hybrid Metaplan

technique using the GCR model. Third, synthesise the

results in a proper set of DG capabilities for designing

a DGMM firmly grounded in the literature. Last,

reflect on the useability of the GCR-model for

identifying capabilities when designing a maturity

model.

102

Merkus, J., Helms, R. and Kusters, R.

Data Governance Capabilities: Maturity Model Design with Generic Capabilities Reference Model.

DOI: 10.5220/0010651300003064

In Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2021) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 102-109

ISBN: 978-989-758-533-3; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 BACKGROUND

Data governance aims to safeguard data assets' value

in alignment with the business (Al-Ruithe, Benkhelifa,

& Hameed, 2018; Brous, Janssen, Vilminko-

Heikkinen, & Herder, 2016; Weber, Cheong, Otto, &

Chang, 2008; Yebenes & Zorrilla, 2019). In doing so,

it aims to to establish data management in and between

organisations to achieve accountability for data assets

assuring quality and access during its life-cycle

(Merkus, Helms, & Kusters, 2019).

For measuring the DG status quo, organizations

can use a MM. In the literature, there are several

DGMMs proposed already (Dasgupta, Gill, &

Hussain, 2019; Heredia-Vizcaíno & Nieto, 2019;

Olaitan, Herselman, & Wayi, 2019a; Permana &

Suroso, 2018; Rifaie, Alhajj, & Ridley, 2009; Rivera,

Loarte, Raymundo, & Dominguez, 2017). Typically,

these MMs consist of two main building blocks:

capabilities and maturity levels (Merkus et al., 2020).

When comparing the maturity levels of existing

DGMMs, it can be observed that they use very similar

maturity levels. And the origins of these maturity

levels can typically be traced back to the CMM model

(Paulk, Curtis, Chrissis, & Weber, 1993) or earlier

staged models (Nolan, 1973). But when we compare

the capabilities identified by the existing DGMMs and

other DG frameworks, it can be observed that they are

very different. And seemingly, they cannot be traced

to a single model or framework.

The origins of the DG capabilities vary. We

identified the following approaches that were used for

choosing the DG capabilities sets (1) Listing Critical

Success Factors was an approach to chart DG

activities and identified the DG capabilities needed for

their successful execution (Al-Ruithe et al., 2018;

Alhassan, Sammon, & Daly, 2019). (2) Categorising

common DG activities and/or capabilities into groups

of mechanisms originating from the field of IT

Governance: structural, procedural and relational

mechanisms (Abraham et al., 2019; S. De Haes & Van

Grembergen, 2004).

Besides the origins of the capabilities, there are

also other differences to be noticed between the

capabilities of the different DGMMs. (1) First, DG

capabilities are presented using different

terminologies, e.g. variables and aspects (Heredia-

Vizcaíno & Nieto, 2019), or objectives and practices

(Rifaie et al., 2009), or DG dimensions and

assessment criteria (Rivera et al., 2017). (2) Second,

the DGMMs share some common capabilities, but

many other capabilities are unique for each DGMM.

(3) Finally, only some of the DGMMs are empirically

validated so that only a part of the presented

capabilities are confirmed (Dasgupta et al., 2019;

Olaitan, Herselman, & Wayi, 2019b; Rifaie et al.,

2009; Rivera et al., 2017).

And over time, the scope of the capabilities

changed from an internal focus towards the external

environment of organisations (Lis & Otto, 2020, 2021;

Otto, 2011). This shift of the scope is familiar to what

happened earlier in the DG related domain of

Information Governance, where a more intra-

organisational scope is applied too (Rasouli, Eshuis,

Trienekens, & Kusters, 2016).

In other words, the DGMMs found in the literature

vary in many different aspects. Therefore, we

conclude that there is no common ground for selecting

DG capabilities for a DGMM. This lack of common

ground results in a wide variety of DG capabilities and

is considered a gap in the literature.

To fill this gap, we will select our own set of DG

capabilities from literature for designing a properly

substantiated DGMM in preparation for validation in

practice.

For developing a MM, a MM development

procedure has already been formulated (Becker et al.,

2009). A MM aims to describe the status quo of

organisational behaviour or activities in the selected

design area on a maturity scale by assessment criteria

for a selection of area capabilities (Becker et al.,

2009). These area capabilities are often reused from

other MMs to ground the artefact design on literature

(Becker et al., 2009; Hüner et al., 2009). In addition to

basic MM design principles for more reliability,

descriptive MM design principles are given to obtain

objectivity and prescriptive principles to achieve

validity (Pöppelbuss, Niehaves, Simons, & Becker,

2011; Pöppelbuss & Röglinger, 2011; Röglinger,

Pöppelbuss, & Becker, 2012). These development

procedure steps and principles are validated in

multiple studies when comparing maturity models

(Cleven, Winter, Wortmann, & Mettler, 2014; Tarhan,

Turetken, & Reijers, 2016; Van Looy, de Backer, &

Poels, 2011).

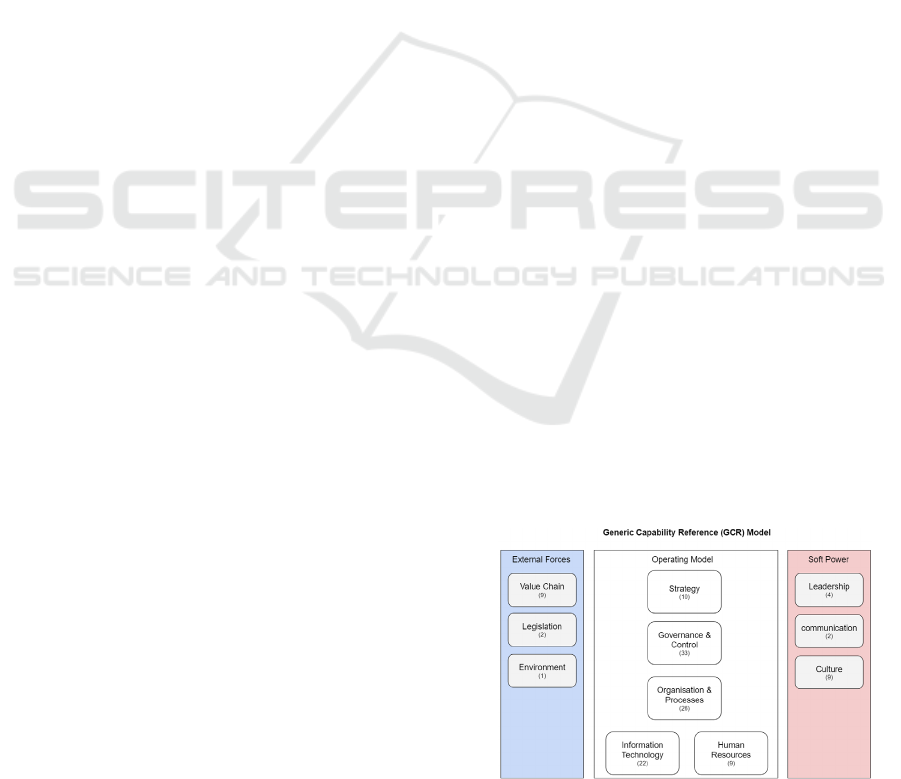

Figure 1: Generic Capability Reference Model(Merkus et

al.,2020).

Data Governance Capabilities: Maturity Model Design with Generic Capabilities Reference Model

103

Lately, a reference model was added to enrich this

MM design process model for validating generic and

area-specific capabilities; see figure 1 Generic

Capability Reference Model (Merkus et al., 2020).

Only, this reference model has not yet been

validated. To do so, we will apply this GCR-model

to the set of DG capabilities from literature, resulting

in a validated list of DG capabilities and a first

validation of the GCR-model.

3 METHOD

To find a proper set of DG capabilities as part of the

MM design, we adopt the MM design procedure

model according to Becker et al. We follow the four

initial procedure steps necessary for finding and

validating DG capabilities as a MM section. The

following steps in the procedure model remain for

further research. We applied the procedure model

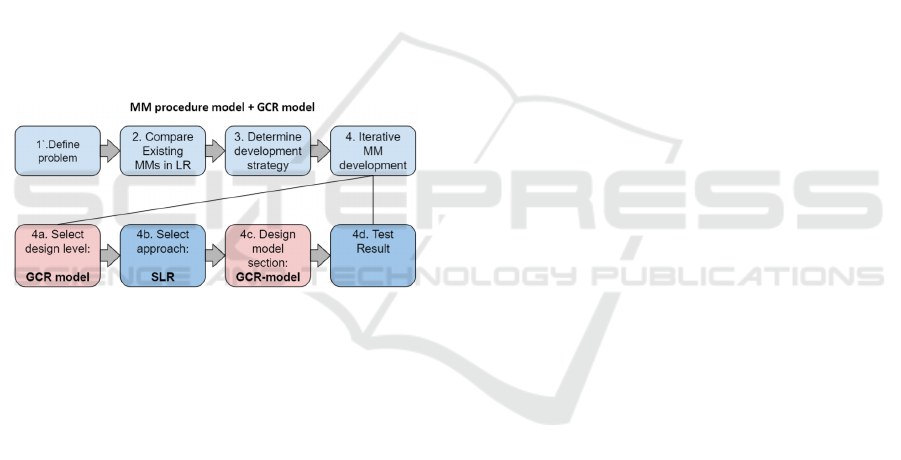

steps as shown in Figure 2 MM procedure model +

GCR model.

Figure 2: MM procedure model + GCR model.

This figure corresponds to the original procedure

model concerning the standard letter display. Our

additions are in bold. For sub-step 4a design level, we

apply the GCR model. For sub-step 4b, we perform

SLR to find DG capabilities. And for sub-step 4c, we

apply the GCR model to classify the DG capabilities

found in the former sub-step 4b and validate the GCR

model. For sub-step 4d, the resulting set of DG

capabilities would need the test of this result,

followed by the next steps of the MM procedure

model like validation in real-life organisational

environments. This is for further research.

Step 1 and step 2 are described in the theoretical

background above .Step 4d is left for further research.

The remaining steps are elaborated as follows.

Step 3 Determine Development Strategy.

According to step 3 of the procedure model of

Becker, we determine the MM development strategy

by elaborating the four sub-steps for step 4, Iterative

MM development. Chapter 4 Results presents the

results of step 4. Following the prescriptions of the

procedure model of Becker, we choose the following

application.

Sub-step 4a Design Level. For the design level of the

DGMM, we choose the GCR model as the highest

level of abstraction because it is in line with previous

research, brings sufficient abstraction rather than

being too detailed and offers diversity in capabilities

for designing MMs (Merkus et al., 2020). This

reference model gives the DGMM architecture

multiple generic dimensions.

Sub-step 4b Systematic Literature Review. Our

approach is to find DG capabilities in SLR by

searching for DG capabilities in existing DGMMs

and other DG frameworks in systematic literature

research. We will apply the following steps

iteratively,

a. We will search articles with the search string “Data

Governance Maturity Model” in Google Scholar and

Open Universiteit library. We will also apply forward

and backwards snowballing for more relevant

articles.

b. we will apply inclusion and exclusion criteria to the

set of found articles. Articles selected based on

inclusion criteria will be reviewed and possibly de-

selected based on exclusion criteria to ensure the

quality of the study. (i) As inclusion criteria, we will

only select articles related to research on DG in IS.

Furthermore, we will only select blind double peer-

reviewed articles written in English, online available

and remove duplicates.

(ii) As exclusion criteria, we will exclude articles that

have not been published in a journal or conference

with ranking A, B or C according to journal or

conference ranking websites, e.g. ERA.

c. We will extract and combine all capabilities from

the selected articles in one resulting list of potential

DG capabilities.

Sub-step 4c Design DGMM Capabilities with GCR

Model. We design the DGMM capability section by

classifying the DG capabilities found in SLR with the

GCR model thus validating whether the GRC model

covers the required scope.

Consequently, we plan the classification of

harvested DG capabilities. Classification is required,

since the results from the SLR will be partly

overlapping, contain homonyms and synonyms, and

will deliver results at different levels of abstraction.

We classify these DG capabilities with the GCR-

model as a reference model for designing MMs but

leave the option open for other DG capability

dimensions. This closed and open classification has a

hybrid character. It is closed for classifying generic

KMIS 2021 - 13th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

104

capabilities provided by the reference model.

Moreover, it is open for any area-specific capabilities

for which no categories are defined yet. This aspect

of the approach will test the usability of the GRC-

model. If the model scope is sufficient, and no

additional areas are required, this is a good test of the

model. The classification is simultaneously executed

in a group of three peers, all researchers of DG and

MMs. This odd number of participants excludes

stalemate when making decisions. And three

researchers prevent researcher bias. Also, a smaller

number of participants improves quick, intuitive

classification as intended by classification approach.

Moreover, expert knowledge is assured by inviting

only subject matter experts. As a classification

approach, the Metaplan technique was selected since

it has proven its usefulness in previous research

(Howard, 1994; Merkus et al., 2019). Because of its

brainstorming nature, this research technique is

usually executed on paper with yellow sticky notes

(Harboe & Huang, 2015; Howard, 1994).

The Metaplan technique will be applied as

follows. We will conduct research using an online

collaboration tool. The ‘online’ format was chosen

because of the prevailing Covid’19 pandemic and

health precautions. For each of the capabilities

collected in SLR, yellow sticky notes will be created

on an online virtual board. For classifying the

capabilities, virtual boxes are created for each GCR

group and empty space when no GCR group is

applicable. When executing the Metaplan online, the

researchers will drag and drop the digital cards into

the relevant group boxes or outside the group boxes

when no relevant GCR groups are applicable. The

cards in each GCR group and the not grouped cards

will be classified even further for each group to find

more generic or more area-specific DG capabilities.

Validity and Reliability. Evaluating the validity and

reliability of this research, we consider four aspects;

construct validity, internal validity, external validity

and reliability (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2015).

To obtain construct validity, we tried to improve

the reliability of the collected data. We applied SLR

as a research method for grounding on literature

comparing existing DGMMs and DG frameworks

with applying inclusion and exclusion criteria for

quality improvement and excluding unpublished

research material to advance research quality.

To improve internal validity, the reliability of our

conclusiuon are improved by applying the following

measures. (1) We classified the DG capabilities found

against the (GC) reference model based on existing

organisational readiness MMs, aimed at connecting

with similar research. (2) Furthermore, we researched

with three researchers in this research area for peer

scrutiny. (3) By applying the MM design procedural

model of Becker, we based our initial MM design on

research that compared several Business Process

Management MM designs and thus improved the

suitability of the MM that we design as a measurement

tool. (4) Moreover, we have applied the Metaplan

technique, which is a tried and tested classification

technique, improving the rigor of our research.

To increase external validity, we have sought

connection with existing DGMMs in literature which

was validated. External validity could be further

improved by validating and testing the initial MM in

real-life organisations as further research.

To ensure the reliability of our research, we have

tried to make the research process transparent by

providing a reasonably detailed method description

so that others can check or reproduce our research.

4 RESULTS

We conducted our research according to the above

method in 2020 and early 2021. The results are given

for both research questions.

SLR for DG Capabilities. For finding substantiated

DG capabilities, we conducted literature research to

compare DG capabilities in existing DGMMs and

other DG frameworks in early 2020. When searching

DG capabilities, we found a set of 179 relevant

articles with the search string “Data Governance

Maturity Model”. Other optional search strings

returned too many results to investigate. The search

string "Data governance" AND "critical success

factor" seems adequate, but MM capabilities consist

out of more than CSFs alone (Merkus et al., 2020).

Forward and backwards snowballing resulted in five

more relevant articles, making a total of 184 relevant

articles. As described in table 1 Selection results, we

were left with only 17 articles describing DG

capabilities when applying inclusion and exclusion

criteria.

Next to the six DGMMs (Dasgupta et al., 2019;

Heredia-Vizcaíno & Nieto, 2019; Olaitan et al.,

2019b; Permana & Suroso, 2018; Rifaie et al., 2009;

Rivera et al., 2017) we found six more DG

frameworks (Abraham et al., 2019; Al-Ruithe &

Benkhelifa, 2018; Al-Ruithe et al., 2018; Brous et al.,

2016; Khatri & Brown, 2010; Otto, 2011; Yebenes &

Zorrilla, 2019). Additionally, snowballing result in

five other DG frameworks (Alhassan, Sammon, &

Daly, 2016; Brennan, Attard, & Helfert, 2018;

Janssen, Brous, Estevez, Barbosa, & Janowski, 2020;

Krumay & Rueckel, 2020; Lis & Otto, 2020).

Data Governance Capabilities: Maturity Model Design with Generic Capabilities Reference Model

105

Table 1: Selection results.

Article selection criteria Results

Step 2a articles resulting from search 184

After applying Inclusion criteria 29

After applying Exclusion criteria 17

When extracting capabilities from the article, we

found 123 very different DG capabilities. These

differences demonstrate that researchers disagree on

what DG capabilities include. Sometimes authors

added more granularity to their dimensions or

capabilities with more specific qualifications, which

we excluded from our list because it would not enrich

the DG domain. Three articles contained such highly

abstracted capabilities or dimensions that we decided

to use the sub-dimensions as dimensions because they

were comparable in level of abstraction to dimensions

or capabilities from other research.

DGMM Design with GCR Model. To design

DGMM capabilities with the found DG capabilities in

SLR, classification with the GCR model is executed

in late 2020 and by three peers who all research data

governance and maturity models. Furthermore,

because of the absence of an online Metaplan tool, we

selected an online tool for affinity diagramming

technique that enabled online card sorting research

instead of paper.

Of the 123 DG capabilities we found in SLR, we

created 123 digital cards in the online collaboration

tool to create the affinity diagram for DG capabilities.

Together with peers, we grouped all 123 digital cards

into groups, in fit with the GCR model and adding

other categories when necessary. For the results. see

table 2 Capabilities Distribution.

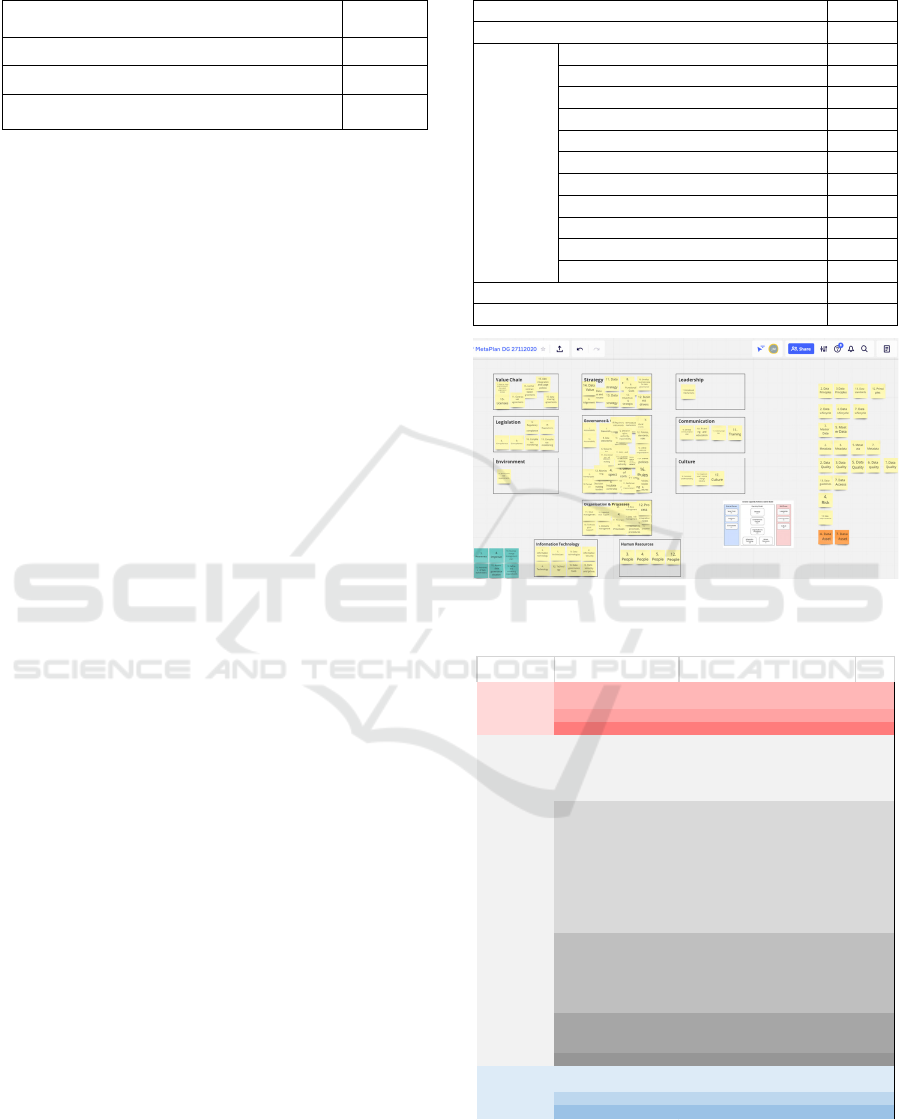

The outcome of the online classification of all

found capabilities against the GCR-model is

presented in a screenshot in figure 3.

Most of the digital cards could be classified

according to the predefined groups of the GCR model

(94) but not all. The remaining cards (29) contained

non-relevant DG aspects such as data management

capabilities or even maturity criteria which were

considered to be out of scope for our purpose.

Moreover, we found zero DG area-specific

capabilities (0), giving a correct first validation of the

GRC-model, since it did seem to cover all aspects

required. We did make one change to this model

when we decided that the capability group

Organisation & Processes could improve into

Organisation Management & Processes because the

capabilities concerned only management activities or

processes.

Table 2: Capabilities Distribution.

cards

Generic DG ca

p

abilities 94

Leadershi

p

1

Culture 3

Communication 4

Strateg

y

10

Governance & Control 35

Mana

g

ement & Processes 16

Information Technolo

gy

8

Human Resources 4

Value Chain 6

Environment 1

Le

g

islation 6

Area-s

p

ecific DG ca

p

abilities 0

Total 94

Figure 3: Screenshot Online Metaplan outcome based on

the GCR-model.

Figure 4: Data Governance Maturity Model capabilities.

Further classifying of the cards within each GCR-

group resulted in a final list of distinct DG

Cluster Dimension Capability

#Cards

SoftPower Communication Communicate 1

Train 2

Leadership Lead 2

Culture Changeculture 3

OperatingModel Strategy Quantifydatavalue 2

Alignwiththebusiness 1

Formulatedatastrategy 2

Makebusinesscase 1

Setgoals&objectives 4

CoreGovernance&Control Establishaccountability 2

Establishdecisionmakingauthority 5

Establishcommittees 1

Establishroles&responsibilities 6

Establishdatastewardship 3

Establishpolicies,principles,procedures 11

EstablishKPI's 1

Establishperformancemanagement 3

EstablishMonitoring 2

EstablishAuditing 1

OrganisationManagement Manageprocesses 7

&Processes Managedata 5

Managemetadata 1

Manageorganisation 1

Managerisk 1

Manageissues 1

InformationTechnology Setupsecurity&privacy 1

SetupDGtools 1

SetupIT 2

HumanResources Organizepeople 4

ExternalForces ValueChain Align&integratedata 1

Contractdatasharingagreements 5

Environment Establishenvironmentalresponse 6

Legislation Complywithregulations 1

KMIS 2021 - 13th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

106

capabilities. The synthesis of the classification

outcomes into a list of DG capabilities organised

according to the GCR model, including the number of

cards per DG capability, is given in figure 4 Data

Governance Maturity Model capabilities. These DG

clusters, dimensions and capabilities can, after further

validation in practice, be used to design a DGMM.

5 CONCLUSION, DISCUSSION,

AND LIMITATIONS

Concluding, we determined a list of relevant DG

dimensions and capabilities in SLR as a result of our

initial MM design. This outline of the DG area can be

used to continue designing a DGMM. This outline of

the DG area may also serve as a basis for further DG

research or education.

When using the GCR-model in MM design to

classify the found DG capabilities, we disqualified 29

of the 123 capabilities found, being 24% of all. This

percentage indicates insufficient clarity on what

should or should not be included as a capability in a

DGMM. Moreover, we found that the GCR model

can support a focus on a consistent interpretation of

the concept of capability.

Another conclusion is that the absence of area-

specific capabilities supports the validity of the GCR

model as a reference model for designing MMs.

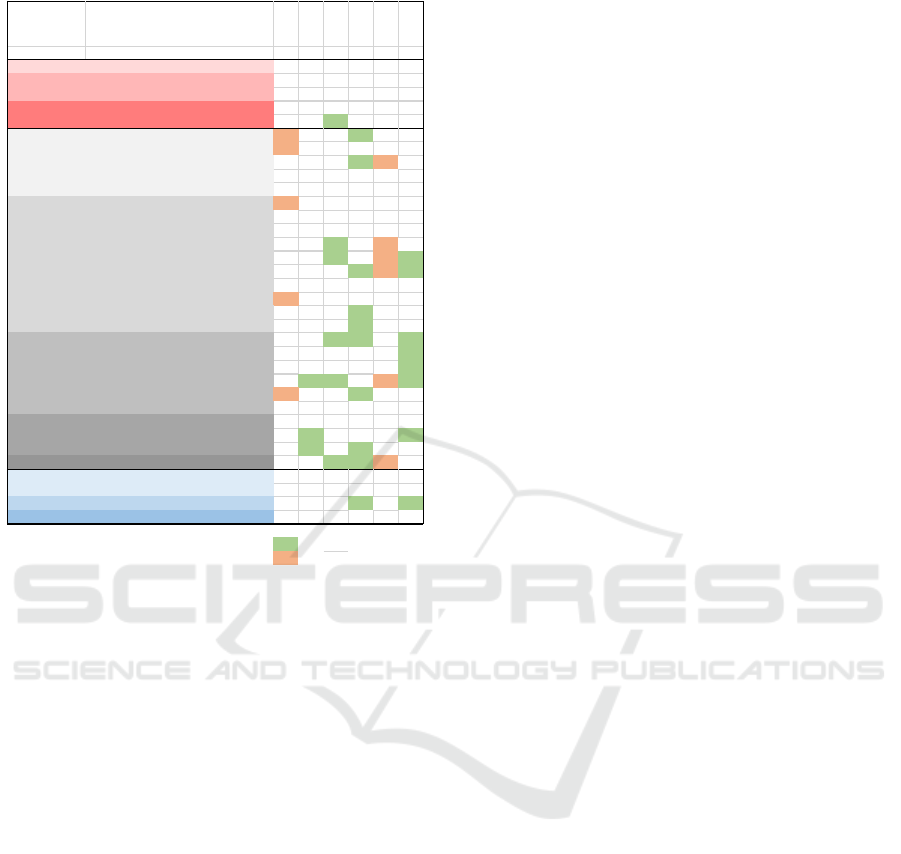

When comparing our results with the earlier

DGMMs found, several interesting observations can

be made. For comparison, we have compared the DG

capabilities of each of the six DGMMs found in our

SLR together with the DG capability set resulting

from our classification, see table 3 DG capability sets

comparison.

Table 3 clearly shows that designers of existing

DGMMs disagree on a single set of DG capability,

supporting the claim made in section 2. Table 3 also

shows 14 more relevant DG capabilities than the 20

used in existing DGMMS which originate from other

DG frameworks and which fit the GCR model.

Furthermore, classifying the found DG

capabilities found in SLR against the GCR-model

uncovers generic MM capabilities for DGMM design

and clearly shows differences between existing

DGMMs. It is noteworthy that three DG capabilities

in non-validated DGMMs which are not supported by

other DGMMS are still supported by the GCR model.

So, the GCR-model provides a broader view of MM

capabilities, resulting in a more diverse set of DG

capabilities. This uncovered set of generic DG

capabilities may serve as research agenda for

designing a DGMM specifically or DG research in

general.

An interesting result is that we found substantial

proof for extra-organisational dimensions in other DG

frameworks (cluster External Forces, coloured blue)

which are absent in existing DGMMs but which are

supported by the GCR model. Also, we found proof for

the dimensions Leadership & Culture (cluster Soft

Power, coloured red), which are missing in existing

DGMMs but supported by the GCR model.

We see an interest in the GCR model capabilities

group Strategy (Brennan et al., 2018). There is an

even greater interest for the DG capabilities group

Governance & Control and the capability group

Organisation, Management & Processes (Brous et

al., 2016; Khatri & Brown, 2010; Weber et al., 2008).

Just like the groups Information Technology and

Human Resources, which both depend on other more

advanced research areas (Steven De Haes & Van

Grembergen, 2008; Schein, 2004). Furthermore, for

the specific DG capabilities establishing & managing

awareness and also for compliance as DG is

increasingly required by law, e.g. Sarbanes-Oxley,

Basel I-V, GDPR or the latest EU law on DG

(Marelli, Lievevrouw, & Van Hoyweghen, 2020).

Hence, existing DGMMs measure the DG status quo

for most capabilities in the DG capability cluster

Operating Model of the GCR model together with the

capabilities awareness and compliance. We see that

these capabilities (groups) rather focus on the internal

organisation or risk mitigation.

We also see no interest in the specific DG

capabilities making business cases and setting goals

& objectives, nor identifying KPI’s although these

capabilities were found relevant in other MMs

according to the GCR model. These missing

capabilities could indicate that not all relevant DG

capabilities have yet been explored to measure DG

precisely, as a whole and so accurately. In particular,

the setting of objectives aligned with the business to

measure results in terms of specific KPIs.

In addition, we already saw a widening scope in

nearby research areas of DG towards an organisations

external environment in section 2, which is supported

by other DG frameworks and the GCR model but not

yet present in existing DGMMs.

Moreover, the most noticeable absent capability

group is Leadership, Culture and Communication.

This uncovered area indicates a gap in the body of

knowledge and might explain why DG is not yet on

organisational boards priority lists (Alhassan,

Sammon, & Dal, 2018).

Data Governance Capabilities: Maturity Model Design with Generic Capabilities Reference Model

107

Table 3: DGMM capability sets comparison.

It can be concluded that existing DGMMs only

include 20 of the 34 relevant DG capabilities

identified by this research. They might miss accuracy

on DG goals & objectives, rather focus on the internal

organisation or risk mitigation and lack leadership

and culture capabilities. Therefore, DG is not yet

accurately described or measured adequately within

organisations, let alone across organisations, because

the used sets of DG capabilities are incomplete and

therefore still unclear. This lack of a precise DG

measure indicates a substantial need for further DG

research, both theoretically and in practice.

The study has some limitations. It is limited to the

DGMMs and DG frameworks selected in SLR. We

have not considered DG capabilities of other DG

studies, which could extend or confirm the presented

set DG capabilities, although validation with the GCR

model should prevent this.

Also, the set DG capabilities needs validation in

practice. Further research is necessary to validate the

outcomes of this research. We recommend to finalise

the MM design process steps by completing the

design of the DGMM and validate the designed

DGMM per capability and as a whole.

We also suggest applying the GCR model to

further research (re-)designing MMs and apply the

model to other governance areas.

REFERENCES

Abraham, R., Schneider, J., & Brocke, J. vom. (2019). Data

Governance : A conceptual framework , structured

review , and research agenda. International Journal of

Information Management (IJIM).

Al-Ruithe, M., & Benkhelifa, E. (2018). Determining the

enabling factors for implementing cloud data

governance in the Saudi public sector by structural

equation modelling. Future Generation Computer

Systems. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2017.12.057

Al-Ruithe, M., Benkhelifa, E., & Hameed, K. (2018). A

systematic literature review of data governance and

cloud data governance. Personal and Ubiquitous

Computing, pp. 839–859.

Alhassan, I., Sammon, D., & Dal, M. (2018). Data

governance activities: a comparison between scientific

and practice-oriented literature. Journal of Enterprise

Information Management, Vol 31(2), 300–316.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090910954864

Alhassan, I., Sammon, D., & Daly, M. (2016). Data

governance activities: an analysis of the literature.

Journal of Decision Systems, 25(S1), 64–75.

Alhassan, I., Sammon, D., & Daly, M. (2019). Critical

Success Factors for Data Governance: A Theory

Building Approach. Information Systems Management,

36(2), 98–110.

Becker, J., Knackstedt, R., & Poeppelbuss, J. (2009).

Developing Maturity Models for IT Management – A

Procedure Model and its Application. Business &

Information Systems Engineering, 1(3), 213–222.

Brennan, R., Attard, J., & Helfert, M. (2018). Management

of data value chains, a value monitoring capability

maturity model. ICEIS 2018 - Proceedings of the 20th

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems, 2(January), 573–584.

https://doi.org/10.5220/0006684805730584

Brous, P., Janssen, M., Vilminko-Heikkinen, R., & Herder,

P. (2016). Coordinating decision-making in data

management activities: A systematic review of data

governance principles. In Lecture Notes in Computer

Science (Vol. 9820 LNCS, pp. 573–583).

Cleven, A. K., Winter, R., Wortmann, F., & Mettler, T.

(2014). Process management in hospitals: an

empirically grounded maturity model. Business

Research, 7, 191–216.

Dasgupta, A., Gill, A., & Hussain, F. (2019). A conceptual

framework for data governance in IoT-enabled digital

IS ecosystems. DATA 2019 - Proceedings of the 8th

International Conference on Data Science, Technology

and Applications, (Data), 209–216.

https://doi.org/10.5220/0007924302090216

De Haes, S., & Van Grembergen, W. (2004). IT

Governance and its Mechanisms. Information Systems

Control Journal, 1, 27–33.

De Haes, Steven, & Van Grembergen, W. (2008). Analysing

the relationship between IT governance and business/IT

alignment maturity. Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences.

CapabilityGroup Merkusetal.

Rifae

Rivera

Permana

Dasgupta

Heredia

Olaitan

2021 2009 2017 2018 2019 2019 2019

Leadership EstablishLeadership

Communication Establish&manageCommunicate

Establish&manageTrain

Culture Establish&manageculture

Establish&manageawareness

Strategy Quantifydatavalue

Alignwiththebusiness

Formulatedatastrategy

Makebusinesscase

Setgoals&objectives

Governance Establishaccountability

&Control Establishdecisionmakingauthority

Establishcommittees

Establishroles&responsibilities

Establishdatastewardship

Establishpolicies,principles&procedures

EstablishKPI's

Establishperformancemanagement

EstablishMonitoring

EstablishAuditing

Organisation Manageprocesses

Management Manageorganisation

&processes Managedata

Managemetadata

Managerisk

Manageissues

Information Establish&manageDGtools

Technology Establish&managesecurity&privacy

Establish&manageDataTechnology

Human Organizepeople

ValueChain Align&integratedata

Contractdatasharingagreements

Legislation Complywithregulations

Environment Government

5361068

Validatedinpractice

Notvalidatedinpractice

KMIS 2021 - 13th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

108

Harboe, G., & Huang, E. M. (2015). Real-world affinity

diagramming practices: Bridging the paper-digital gap.

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems -

Proceedings, 2015-April(July), 95–104.

Heredia-Vizcaíno, D., & Nieto, W. (2019). A Governing

Framework for Data-Driven Small Organizations in

Colombia. In WorldCIST (Vol. 1). Springer, Cham.

Howard, M. S. (1994). Quality of Group Decision Support

Systems: a comparison between GDSS and traditional

group approaches for decision tasks. Technical

University Eindhoven.

Hüner, K. M., Ofner, M., Otto, B., Huner, K. H., Martin,

O., & Otto, B. (2009). Towards a maturity model for

corporate data quality management. In Proceedings of

the 2009 ACM symposium on Applied Computing - SAC

’09 (p. 231). New York, New York, USA: ACM Press.

Janssen, M., Brous, P., Estevez, E., Barbosa, L. S., &

Janowski, T. (2020). Data governance: Organizing data

for trustworthy Artificial Intelligence.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101493

Khatri, V., & Brown, C. V. (2010). Designing data

governance. Communications of the ACM, 53(1).

Krumay, B., & Rueckel, D. (2020). Data Governance and

Digitalization – A Case Study in a Manufacturing

Company Data Governance and Digitalization – A Case

Study in a Manufacturing Company. In Twenty-Third

Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems. Dubai.

Lis, D., & Otto, B. (2020). Data Governance in Data

Ecosystems – Insights from Organizations Association

for Information Systems Strategic and Competitive

Uses of IT Data Governance in Data Ecosystems –

Insights from Organizations.

Lis, D., & Otto, B. (2021). Towards a Taxonomy of

Ecosystem Data Governance. In Proceedings of the 54th

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Marelli, L., Lievevrouw, E., & Van Hoyweghen, I. (2020).

Fit for purpose? The GDPR and the governance of

European digital health. Policy Studies, 41(5), 447–467.

Merkus, J., Helms, R., & Kusters, R. (2020). REFERENCE

MODEL FOR GENERIC CAPABILITIES IN

MATURITY MODELS. In 12th ICIME Conference.

Amsterdam.

Merkus, J., Helms, R. W., & Kusters, R. J. (2019). Data

Governance and Information Governance : Set of

Definitions in Relation to Data and Information as Part

of DIKW. In ICEIS 2019 - Proceedings of the 21th

International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems (p. 12). Crete.

Nolan, R. L. (1973). Managing the Computer Resource: A

Stage Hypothesis. Communications of the ACM, 16(7),

399–405. https://doi.org/10.1145/362280.362284

Olaitan, O., Herselman, M., & Wayi, N. (2019a). A Data

Governance Maturity Evaluation Model for government

departments of the Eastern Cape province, South Africa.

SA Journal of Information Management, 21(1), 1–12.

Olaitan, O., Herselman, M., & Wayi, N. (2019b). A Data

Governance Maturity Evaluation Model for government

departments of the Eastern Cape province, South Africa.

SA Journal of Information Management, 21

(1).

Otto, B. (2011). A Morphology of the Organisation of Data

Governance. In ECIS 2011 (p. 272). Helsinki, Finland.

Paulk, M. C., Curtis, B., Chrissis, M. B., & Weber, C. V.

(1993). The capability maturity model for software.

Software Process Improvement, 1–26.

Permana, R. I., & Suroso, J. S. (2018). Data Governance

Maturity Assessment at PT. XYZ. Case Study: Data

Management Division. Proceedings of 2018

International Conference on Information Management

and Technology, ICIMTech 2018, (September), 15–20.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIMTech.2018.8528142

Pöppelbuss, J., Niehaves, B., Simons, A., & Becker, J.

(2011). Maturity Models in Information Systems

Research: Literature Search and Analysis.

Communications of the Association for Information

Systems, 29(1), Article 27.

Pöppelbuss, J., & Röglinger, M. (2011). What makes a

useful maturity model? A framework of general design

principles for maturity models and its demonstration in

business process management. Ecis, Paper28.

Rasouli, M. R., Eshuis, R., Trienekens, J. M., & Kusters, R.

J. (2016). Information Governance as a Dynamic

Capability in Service Oriented Business Networking. In

Collaboration in a Hyperconnected World (Vol. 480,

pp. 457–468). Springer.

Rifaie, M., Alhajj, R., & Ridley, M. (2009). Data

governance strategy: A key issue in building enterprise

data warehouse. In iiWAS2009 (pp. 587–591).

Rivera, S., Loarte, N., Raymundo, C., & Dominguez, F.

(2017). Data Governance Maturity Model for Micro

Financial Organizations in Peru. In Proceedings of the

19th International Conference on Enterprise

Information Systems (pp. 203–214).

Röglinger, M., Pöppelbuss, J., & Becker, J. (2012). Maturity

models in business process management. Business

Process Management Journal, 18(2), 328–346.

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2015).

Research Methods for Business Students (7th editio).

Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Schein, E. H. (2004). Organizational culture and

leadership. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

(Third, Vol. 1). Jossey-Bass.

Tarhan, A., Turetken, O., & Reijers, H. A. (2016). Business

process maturity models: A systematic literature review.

Information and Software Technology, 75, 122–134.

Van Looy, a., de Backer, M., & Poels, G. (2011).

Questioning the Design of Business Process Maturity

Models. Proceedings of the Sixth SIKS Conference on

Enterprise Information Systems, 51–60.

Weber, K., Cheong, L., Otto, B., & Chang, V. (2008).

Organising Accountabilities for Data Quality

Management-A Data Governance Case Study. Data

Warehousing, 347–362.

Yebenes, J., & Zorrilla, M. (2019). Towards a data

governance framework for third generation platforms.

Procedia Computer Science, 151, 614–621.

Data Governance Capabilities: Maturity Model Design with Generic Capabilities Reference Model

109