Development of Wearable Devices for Measurement of Multiple

Physiological Variables and Evaluation of Emotions by Fingerprints

and Population Hypotheses

Martin Malčík, Miroslava Miklošíková and Tomáš Zemčík

Department of Social Sciences, VSB-Technical University of Ostrava, 17. Listopadu 15, Ostrava, Czech Republic

Keywords: Electrodermal Activity, Galvanic Skin Response, Heart Rate Variability, Wearable Devices, Emotion

Diagnostics.

Abstract: We live in an age in which technology provides us with constant access to virtual online services.

Consumption and production of an immense amount of instant data, which is becoming the basic raw material

autonomously processed by artificial intelligence algorithms, open up brave new possibilities and levels of

research and its application in many traditional scientific disciplines. Biometrics is one of the disciplines

experiencing an unexpected renaissance, owing to the wide availability of cheap sensory technologies

connected to the network. We find great untapped potential, especially in devices that allow measuring the

body’s physiological responses to emotional stimuli, such as heart rate (HR) and electrodermal activity

(EDA), also known as galvanic skin response (GSR). Many readily available and professional wearable

devices provide digital recordings of these variables. However, each of these technologies suffers from

multiple shortcomings. These shortcomings stand in the way of the mass popularization of the technology,

which enables, among other things, real-time monitoring and digital recording of the body’s physiological

reactions to emotional stimuli. In other words, creating big data that can be used for digital, automated

reconstruction of certain aspects of emotionality. In our research, we have identified three main social areas

where these technologies are of interest: laboratories, professionals working with the human psyche-body-

emotionality, and regular users of biofeedback devices such as wearable devices (WD). Each of these groups

has specific requirements in terms of the hardware implementation of the technology, and software and

measurement methodology open to users. In our emotion laboratory, we have developed a series of

comprehensive solutions, Sensetio, based on a thorough analysis of the needs of all three groups of users of

biofeedback technologies. We intend to obtain standardized big data sets for further thorough scientific

analysis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Every emotion experienced is accompanied by

physiological reactions of the organism. These

include, for example, changes in facial expressions,

behaviour, perception and also the reactions of the

autonomic nervous system (ANS). These changes in

ANS activity are most frequently measured in the

field of biometrics by physiological records of heart

rate, respiration or sweat gland activity, etc. In the

field of biometrics of emotions, there has been over a

century-long debate whether ANS changes initiated

by specific stimuli connected with specific emotions

or more generally witch a specific emotional

category, can be used to retroactively reconstruct the

category of that emotion. Whether we can recognize

an emotion category by simply measuring the ANS

response.

The most used model of emotion categories

contains five basic emotions: happiness, sadness,

disgust, anger and fear. However, there is still no

scientific consensus on whether it is possible to

determine – from the record of an ANS activity – the

experienced emotion; that is, whether there is a

typical model of an ANS record for individual

emotion categories. Therefore, it would be ground-

breaking to be able to read from the recording of a

biometric pattern with a high degree of probability

that it is specifically about happiness when

experiencing the emotion of happiness. The record of

the ANS structure typical of happiness could thus be

182

Mal

ˇ

cík, M., Miklošíková, M. and Zem

ˇ

cík, T.

Development of Wearable Devices for Measurement of Multiple Physiological Variables and Evaluation of Emotions by Fingerprints and Population Hypotheses.

DOI: 10.5220/0010367801820188

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2021) - Volume 1: BIODEVICES, pages 182-188

ISBN: 978-989-758-490-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

distinguished, for example, from the pattern typical of

fear. Ideally, it would be possible to determine the

quality, ambivalence or source of this particular

emotion category. However, this is very complicated

and so far no one today can say with certainty that it

is even possible with the deployment of the latest

technological solutions and sufficient source data.

Therefore, the scientific community is opinion-

divided and is still seeking an adequate theoretical

model combining physiologically measurable

variables with objectively or subjectively

experienced states. (Cacioppo, 2004).

The reason is that every unique emotion episode

evoked by a specific stimulus turns out to be full of

artefacts, errors, variations and singularities in real

measurements. The recording of an ANS activity is

not identical for one person at two different times in

response to the same situation (stimulus). Naturally,

the variations in the ANS records between different

test subjects are even greater. There have also been

other age-old disputes about the nature and origin of

these recorded variations of ANS on the same

stimulus. There are two basic hypotheses. One

assumes that these variations are inert and a

functional part of emotions. The second hypothesis

attributes the origin of variations to events that are

epiphenomenal with respect to emotions – that their

source can be, for example, the method used, the

environment, hidden cognitive mechanisms or the

technology itself. (Siegel, et al., 2018).

Two Paradigms in Biometrics of Emotions.

The first is the classic theory of emotions or the

Appraisal Theory of Emotion, which argues that

emotions are formed as the subject evaluates and

assesses the stimuli acting on him. (Moors, 2017) The

classical view of emotions states that specific

emotions experienced within emotion categories

share characteristic patterns, just as each person has

their unique fingerprints by which we can identify

them. Therefore, this paradigm is often based on a

hypothesis known as the emotion fingerprints. This

hypothesis assumes that a thorough analysis can

recognize in the measurements of an ANS activity an

emotion fingerprint and at the same time that different

categories of emotions have different but typical

fingerprints.

It is clear that the feeling of happiness can be

evoked by a different stimulus every time: meeting a

loved one, performing a favourite pastime, ingesting

a substance that changes the state of consciousness or

simply observing happy people. We can reasonably

assume that these different situations will evoke

significant variations in the ANS record and the

fingerprint of happiness. Therefore, within the

hypothesis of emotion fingerprints, a certain degree

of variation from one emotion instance to another is

allowed. However, it is important that the pattern is

always similar enough to identify an emotion

category (such as happiness) and distinguish it from

other emotion categories (such as sadness). Thus,

within the emotion fingerprint hypothesis, it is

assumed that each of the emotion categories has its

own unique ANS fingerprint.

The fingerprint hypothesis is based on a tradition

that assumes an emotion essence. This supposed

emotion essence was to evolve during the species

evolution as an adaptive mechanism. This is an

essential view and can be found already in Darwin’s

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

(Darwin, 1964). The essence in each emotion

category is still the same. Therefore, if a person cries

with happiness, is happy because their child was born,

happy from movement and exercise, from touching a

loved one, or feels happiness due to a substance that

changes the state of consciousness, the same pattern

is activated within the ANS that triggers and regulates

the emotional category of happiness. The essentialist

approach assumes that a certain area of ANS is

responsible for a particular emotional category and is

identical across individuals, physiology, age, or

cultures – it is universally human. It is a kind of

analogy to “the organ of happiness, fear, disgust,

sadness and anger.” And it is the activity in this area

that leaves a typical pattern in biofeedback

measurement, which we can record, recognize and

predict.

This hypothesis has its undeniable pros and cons.

Attempts to trace generally shared patterns in ANS

measurements have repeatedly failed – but they are

the basic precondition for the emotion fingerprint

hypothesis. (Barrett, 2006) From the point of view of

this hypothesis, this is interpreted as evidence that

there are random errors across different emotional

categories that significantly distort ANS

measurements. However, these errors are assumed to

be epiphenomenal with respect to emotions, and thus

do not disprove the assumptions of this hypothesis.

These epiphenomena can be based not only on

individual physiological properties of the organism

and the nervous system, statistical fluctuations or

individual regulatory emotion mechanisms but also

on the imaging methods used or the physical-

technological properties of measuring devices.

Therefore, it can be assumed that it should be possible

to eliminate, filter or mitigate their impact using an

appropriate methodology and technology. However,

this has not yet been confirmed in repeated

experimental findings. This view is therefore

Development of Wearable Devices for Measurement of Multiple Physiological Variables and Evaluation of Emotions by Fingerprints and

Population Hypotheses

183

problematic and practically led to the fact that the

fingerprint hypothesis has never been generally

accepted and scientifically confirmed. (Sterling,

2012).

Among the population models based on

constructivist hypotheses, we can include socio-

constructivist, psychological-constructivist or neuro-

constructive and rational-constructive theories and

their numerous combinations. These constructivist

theories that establish the population hypothesis can

again be traced back to Darwin’s idea (Darwin, On

the Origin of Species, 1923) that all biological

categories, such as species, genus (including the

notion of “life” at the beginning of this classification),

are mere conceptual categories. These are basically

created by the human mind precisely for the purpose

of mental classification. The real content of these

categories are heterogeneous, unique and essentially

non-repeatable individuals.

If we transfer this idea to pattern recognition in

measuring ANS response when measuring emotional

responses, we find that the variations in ANS patterns

are not completely random but contain an internal

meaning and structure. The mentioned structure is a

consequence of the functions of behavioural

interactions with the environment, which differ from

situation to situation, and the situations themselves

are uninterchangeable. However, many structural

similarities can be statistically traced and described –

although they are merely probabilistic concepts, they

tell enough about their nature and reality. Therefore,

it is possible to follow them according to the

principles of causal probability. The patterns of these

variations begin to overlap densely with a sufficient

amount of analysed data from the records at certain

points. The values of the measurements thus form

clusters around certain values– populations begin to

form, which we can already easily delimit and

statistically formulate. Then we can determine with a

certain (and frequently very high) degree of

probability that the measured value is in the range of

the population where the measurements of a certain

emotion category most regularly overlap, even

though that value is essentially singular and

unrepeatable. The uncertainty arising from variations

in measurements between different stimuli in

different situations outside the emotion categories is

therefore not a mistake, they are the essence of the

emotional response. (Clark-Polner, Johnson, &

Barrett, 2017).

The first part of the article describes the

methodological starting points that are used in the

analysis of emotional states of an individual during

the experience of various life situations. Based on

these starting points, technological and hardware

devices called Sensetio were developed. These make

it possible to measure, evaluate and analyse signals

from the measurement of human physiological

variables with the possibility of evaluating the

intensity and quality of experienced emotions.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 The Sensetio Method

The Sensetio method is a unique psychodiagnostic

method based on an exact measurement of the

physiological manifestation of currently experienced

emotions, namely the measurement of skin

conductivity and heart rate variability (Miklosikova,

Malcik, 2019). The method is based on the realisation

that the intensity of physiological expression of

emotions changes under the influence of stress, fear

and anxiety, which allows obtaining objective data

about the psychological state of an individual

(Boucsein, 2012). Measurement can also be done by

recording the emotional activation of a student

throughout their self-presentation, while a specialist

measuring physiological values notes down critical

moments into the system – the so-called nodal points

– a description of specific situations during which the

physiological values of the student changed

significantly (Miklosikova, Malcik, 2017).

Several types of devices with corresponding

software have been developed to measure the

emotional arousal of the organism.

2.2 The Sensetio Devices

The Sensetio devices consist of the Sensetio Mouse,

Sensetio Wristband and Sensetio software. The

Sensetio software uses artificial intelligence

algorithms for GSR curve analysis, the Sensetio

Mouse has been patented by Patent No. 307554, and

the Wireless Sensetio Wristband uses some of the

Sensetio Mouse technologies.

By using the method, it is possible to record

physiological changes in the organism during an

emotional experience, namely skin conductivity and

heart rate variability. This objective data is further

supplemented by a structured diagnostic interview,

which guides the measured person to gain insight into

the experience, its causes and provides

recommendations which should lead to coping with

the problematic situation.

BIODEVICES 2021 - 14th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

184

2.2.1 Biometric Sensetio Mouse

For actual measurements, the GSR mouse (patent

pending) will be used, which uses a six-channel

measurement system between four skin contact points

(see Figure 1). The resulting GSR is then determined

by a neural network that is taught to determine the

actual GSR value by reference from the precision

sensor. At the same time, the mouse measures skin

temperature, heart (HR), and heart rate variability

(HRV) is counted.

Figure 1: Prototype of the biometric mouse with GSR and

HR sensor and palm skin temperature. The four black areas

on the surface of the mouse are made of a conductive plastic

and represent four electrodes for measuring GSR. These

electrodes provide 6 signals, from which the resulting GSR

value is calculated by a special algorithm. The temperature

sensor is located in a small hole on the top of the mouse.

The HR sensor is located in the black area on the left side

of the mouse and the HR is thus read from the thumb of the

right hand.

2.2.2 Bluetooth Sensor Sensetio Wristband

Wireless measurement is used wherever there is a

need for certain motor freedom to perform diagnostic

and performance activities (psychotherapeutic

interview, coaching training, physical and mental

exercise, etc.).

Wireless Bluetooth sensor (see Figure 2) is

mounted on the wrist and two fingers. The signal

transfer is transmitted via the Bluetooth interface to

the PC or tablet where the results are evaluated and

processed and their graphical display is presented

both in the form of a continuous curve from the time

during measurement and as a current and instant

value. The prototype is displayed in the picture

below.

Figure 2: Bluetooth GSR measuring system – a wristband

with finger contacts (left picture), wristband with adhesive

back contacts (right picture).

2.2.2 The Sensetio Software

a) Software for Continuous Measurement -

Sensetio Pro.

For continuous measurement – e.g.

psychotherapeutic interview, coaching training etc. –

the Sensetio Pro software for continuous

measurement is used, which allows to measure and

evaluate GSR or HRV in real-time, to save data, and

later analyse and possibly use it for measuring

progress, outputs and other uses. Continuous

measurement of your experiencing can be realized

during activities that are uncomfortable or stressful

for you, inducing fear or anxiety. Through such

measurement, you will be able to see what is

happening in your body and gradually control and

change your experience through willpower. During

the measurement, sound can be recorded

synchronously and then see the respondent’s

organism react within the individual stimulating

events. Several special algorithms have been

developed for the analysis of peaks during

measurement with the possibility of their evaluation

in terms of assigning them to the experienced life

situations.

Measurements can be saved for later analysis, and

also for graphical outputs in reports, etc. To be able

to set a specific measurement time, if necessary,

Sensetio Pro includes a timer with a range of up to

several hours.

Development of Wearable Devices for Measurement of Multiple Physiological Variables and Evaluation of Emotions by Fingerprints and

Population Hypotheses

185

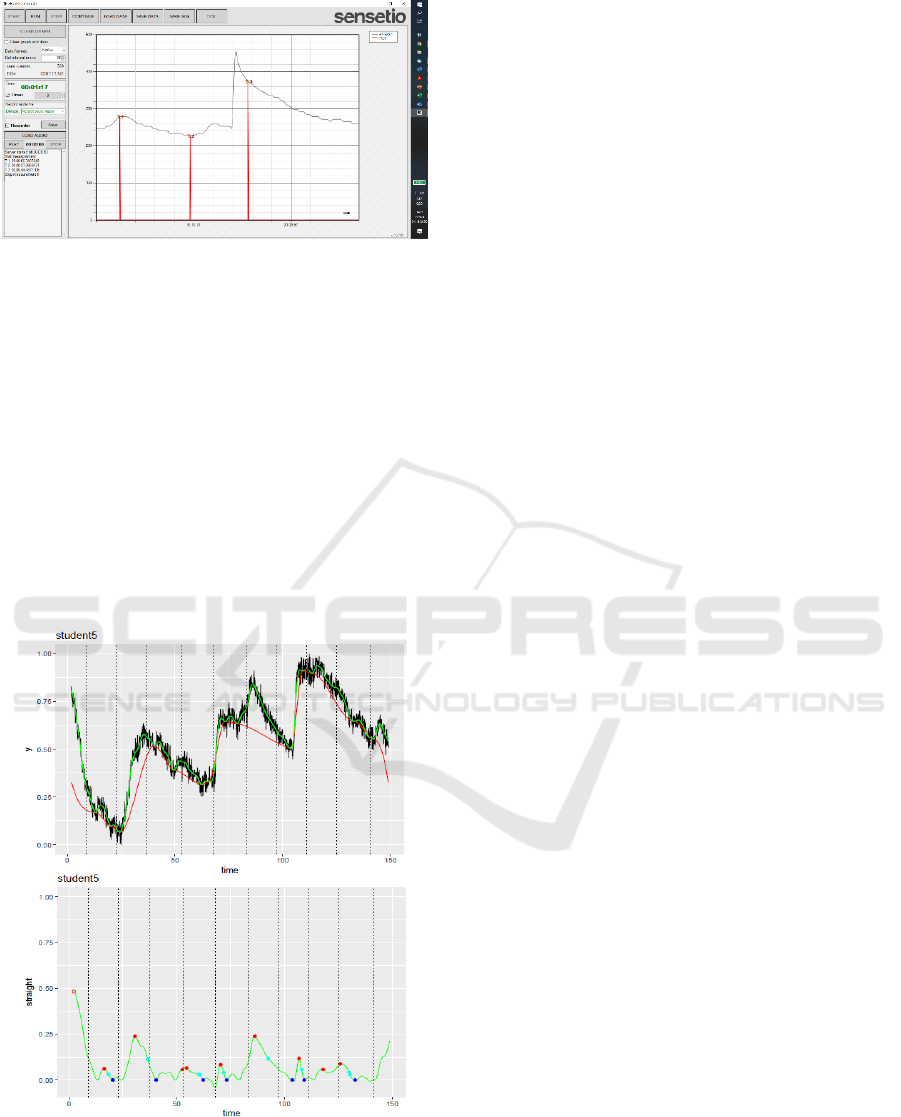

Figure 3: Sensetio Pro – GSR and HRV - mouse

measurement system. Indices T1–T3 are identified

significant events during the measuring. (Source: Authors).

From the point of view of measurement, GSR is

an electrophysiological indicator that significantly

indicates the properties of the nervous system and

thus brain processes. It follows that we can use it to

monitor excitation and inhibition processes, reactivity

to various types of stimuli as well as the process of

adaptation.

And this also results in its significant diagnostic

value and conclusions for assessing the

psychophysiological state of the respondent

(experimental person) in various working or

relaxation conditions.

Figure 4: Sensetio Pro analyzer analyzes raw data,

interleaves them with a baseline curve (graph above),

converts raw data into filtered smoothed data, where peaks,

false peaks, monotonic intervals, etc. are identified (graph

below). (Source: Authors).

Several algorithms have been developed for the

analysis of the measured signal, which diagnose

peaks in the measurement with the possibility of their

evaluation in terms of assignment to the experienced

life situations (see Figure 4).

b) Stimuli-based SW – My Sensetio.

A specialised SW My Sensetio was made for the

stimulated measurement; it triggers the stimulus in

the form of image or audio medium, and at the same

time measures the GSR with precisely defined time

stamps, where the individual parts of the stimulus are

shown to the respondent. The software is customised

so that underlying guidance through the entire

measurement can be inserted into it, including the

introduction and description of the test with an

adjustable timer or click and the possibility of

selecting and providing the individual stimuli in the

form of sentences and time pauses between them with

a timer. The duration of the stimuli exposure is

identical for everyone or can be set dynamically

depending on the decrease of the respondent’s

emotional activity to the normal level. After each

stimulus, the respondent slider is used to express the

emotion experienced in terms of positivity and

negativity and in what strength. Subsequently, a

comparison of cognitive-emotional experience and

the emotional power of the emotions measured as

GSR is evaluated (see Figure 3).

The software, due to the different conductivity

values of the skin of individual respondents,

normalizes the resulting values on a scale of 0-1,

compares similarities of the resulting curves, divide

the respondents by the monotonicity to raising,

decreasing and constant. It further measures the peaks

of individual stimuli with respect to the previous time

delay and selects a set number of them for further

analysis. In the next phase, it can continue testing

interactively by working with the highest selected

peaks and focusing on the selected areas. The

software also manages the initial calibration (the

cube) to measure the truthfulness of responses.

Furthermore, it compares the direction of the curves

and the individual peaks with the likelihood of a false

answer.

c) Sensetio Go Mobile Application.

This is an application that uses the biometric Sensetio

Wristband to clearly record skin conductivity (GSR)

values, which are closely related to the level of

emotional response. The application works on

Android and iOS. The connection with the wristband

can be realized in the application directly via

Bluetooth without unnecessary setting of the mobile

phone. An important feature is where the user has the

BIODEVICES 2021 - 14th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

186

opportunity to upload their videos or photos and then

measure their emotional response to them.

Each user can set individual measurement

parameters, create several profiles, etc. It is also

possible to choose the measurement time or

preparation time before measurement. Based on the

measured data, the application evaluates the

emotional state of the user and then the user is offered

exercises in the form of custom meditation exercises.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

An extensive meta-analysis of hundreds of empirical

studies, 10 qualitative reviews, 4 meta-analyses and a

handful of multi-variable classification analyses of

patterns accumulated over the last 60 years, comes

with findings relevant to the Sensetio project. (Siegel,

et al., 2018) The content of the meta-analysis were

studies that focused on whether emotion categories,

from the point of view of ANS measurements,

correspond more to hypotheses based on fingerprints

or population models. The results revealed that there

are repeated methodological errors, generating

distortions and misleading interpretations that occur

in many studies that deal with the measurement of

emotions, especially those confirming the

fingerprints hypothesis. These errors include

unverified and unverifiable inductive methods,

induction of low-intensity emotions, use of very

simplified models of ANS functioning, incomplete

characterization of ANS response activity, or poor

synchronization of the induced ANS response with

the presented stimulus. Sensetio copes with all these

repeated methodological errors and reacts to them.

The meta-analysis also recommends the future

direction of research to be focused mainly on the

population hypothesis based on constructivist

theories and abandoning the historical consensus of

searching for emotion fingerprints. The authors

believe that the field’s future is rather in mapping

heterogeneity and examining its conditions, states and

probabilistic occurrences than in searching for

stereotypes of patterns in ANS that evoke emotion

categories. Thanks to technological progress, the

present opens the possibility of monitoring and

measuring with new biofeedback devices, like

Sensetio solutions, which are becoming commonly

available and widespread – all thanks to

miniaturization, affordability, availability and a user-

friendly interface. These devices are commonly used

for biohacking, measuring the physiological

responses of the body during sports or normal

activities, in the field of virtual reality or the digital

entertainment industry and others. This introduces

new perspectives for the field, which allows

observations to not always take place only in

laboratory conditions but in the natural environment.

At the same time, the new biofeedback devices

enable the collection of biometric big data with the

prospect of a uniform data format. The big data in turn

– thanks to advances in machine learning and

artificial intelligence, which make it possible to

analyse social and cultural influences – can be used

to revolutionise the creation of “digital traces of real

emotions” when measured in the natural

environment.

Such measurements can help discover individual

and specific traits of a particular unique personality in

different emotion categories adequate for different

contexts – in other words, idiographic models.

Another potency is in finding users who are similar in

these idiographic patterns. This will allow the

creation of group probabilistic prediction models.

Another potential of the research lies in the

search for connections between these probabilistic

idiographic patterns with different linguistic and

cultural contexts, as it has been confirmed that the

experience of emotions is related to the specific

language and cultural environment used.

Furthermore, it is possible to look for new

methodological approaches to refine the

measurement and its predictions or the connection

between the methodology used and the specific socio-

cultural or idiographic context. (Siegel, et al., 2018).

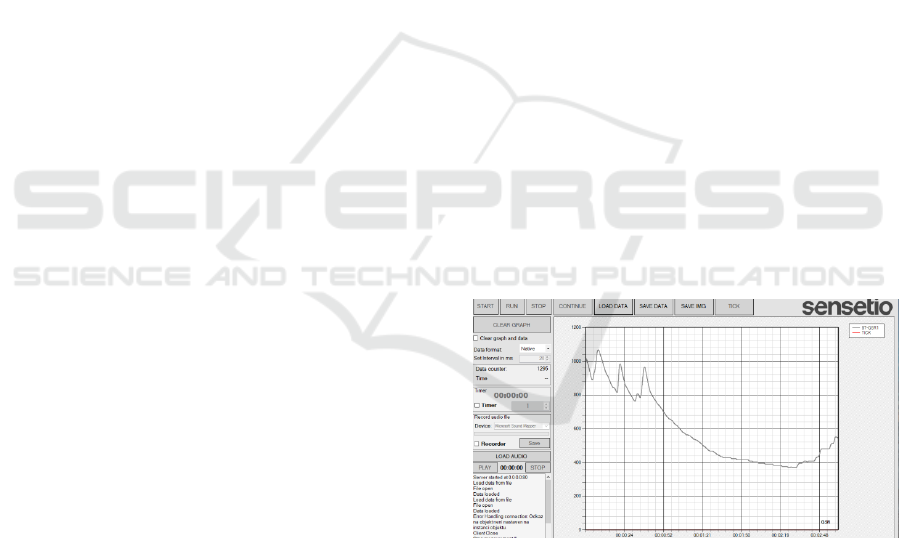

Figure 5: Wristband measurement during

psychotherapeutic interview of respondent. We can see

several peaks at the beginning of the interview. (Source:

Authors).

These findings essentially correspond to our

long-term research goals, we functionally include

them in our implementations and we try to take them

into account in our methodology. We also agree with

other proposed application directions, we supplement

them and add new ones. We have long been exploring

the possibilities of using Sensetio solutions in

Development of Wearable Devices for Measurement of Multiple Physiological Variables and Evaluation of Emotions by Fingerprints and

Population Hypotheses

187

therapies and mental trainings of various kinds (see

Figure 5), in human-machine communication, in e-

sports and traditional sports training, and as a safety

“kill-switch” for operators in contact with mechanical

robots or in the porn and sex equipment industry or in

meditation practice.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The findings from the meta-analysis (Siegel, et al.,

2018) and long-term scientific work of the emotion

laboratory that is implementing the Sensetio solution

can be applied in many fields where it is possible to

use the predictive power of the digital trace of the

measured emotion or where it is necessary to build

idiographic algorithms simulating trends in

individual or group emotionality. An example of such

use may be in the field of persuasive technologies,

which are morally and ethically questionable,

however, and need to be applied consciously,

conscientiously and in accordance with good morals,

legislative trends and institutional developments so as

not to undermine the fabric of social cohesion.

Ethically and legislatively no less controversial

is the use of this knowledge to train communication

algorithms, so-called chatbots. Thus far, this artificial

intelligence can only rather clumsily assign a specific

meaning to the syntax when talking to the user. This

is largely because one sentence, spoken in different

situations under the influence of different emotions,

can have different and even incommensurable

meanings. Assigning an emotional vector of the user

to a syntactic sentence structure would lead to a

breakthrough in human-machine communication.

Generally speaking, it can be argued that

development in this discipline can be useful in any

field where we work with a digital record, model or

algorithm representing a real user’s emotion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by an R&D project Eta,

TL01000299 from the budget of the Czech Republic.

REFERENCES

Barrett, L. F., 2006. Are Emotions Natural Kinds?

Perspectives on psychological science, 1(1), pp. 28-58.

doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00003.x

Boucsein, W., 2012. Electrodermal activity, NewYork:

Springer, 2012.

Cacioppo, J. T., October 2004. Feelings and emotions: roles

for electrophysiological markers. Biological

Psychology (67), pp. 235–243.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.009

Clark-Polner, E., Johnson, T. D., & Barrett, L. 2017.

Multivoxel Pattern Analysis Does Not Provide

Evidence to Support the Existence of Basic Emotions.

Cerebral Cortex, 27(3), stránky 1944–1948.

doi:doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw028

Darwin, C., 1923. O původu druhů. Praha: Dědictví

Havlíčkovo.

Darwin, C., 1964. Výraz emocí u člověka a u zvířat.

Československá akademie věd.

Levenson, R., 2011. Basic emotion questions. Emotion

Review(3), stránky 379–386.

doi:dx.doi.org/10.1177/1754073911410743

Lewenson, R. W.. 2014. The autonomic n.ervous system

and emotion. Emotion Review(6), stránky 100 –112.

doi:doi.org/10.1177/1754073913512003

Miklošíková, M., Malčík, M., 2017. Learning Styles of

Students as a Factor Affecting Pedagogical Activities

of a University. In: iJET – International Journal of

Emerging Technologies in Learning. Vienna:

International Association of Online Engineering

(IAOE), vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 210 - 218.

Miklošíková, M., Malčík, M., 2019. Study Results of

University Students in the Context of Experiencing

Positive Emotions, Satisfaction and Happiness. In: iJET

– International Journal of Emerging Technologies in

Learning. Vienna: International Association of Online

Engineering (IAOE), vol. 14, no. 23, pp. 260 - 269.

ISSN 1863-0383.

Moors, A., 2017. Appraisal Theory of Emotion. V T. K.

Virgil Zeigler-Hill, Encyclopedia of Personality and

Individual Differences (stránky 1-9). doi:DOI

10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_493-1

Siegel, E. H., Sands, M. K., Van den Noortgate, W.,

Condon, P., Quigley, K. S., & Barrett, L. F., 2018.

Emotion Fingerprints or Emotion Populations? A Meta-

Analytic. Psychological Bulletin, 144(4), pp 343–393.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000128

Sterling, P., 2012. Allostasis: A model of predictive

regulation. Physiology & Behavior(106), pp 5-15.

doi:doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.06.004

BIODEVICES 2021 - 14th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

188