Voice Interaction for Accessible Immersive Video Players

Chris J. Hughes

1a

and John Paton

2b

1

School of Science, Engineering & Environment, University of Salford, U.K.

2

RNIB, 105 Judd Street, London, WC1H 9NE, U.K.

Keywords: Voice Interaction, Immersive Video, User Interface, Accessibility.

Abstract: Immersive environments present new challenges for all users, especially those with accessibility

requirements. Once a user is fully immersed in an experience, they no longer have access to the devices that

they would have in the real world such as a mouse, keyboard or remote control interface. However these users

are often very familiar with new technology, such as voice interfaces. A user study as part of the EC funded

Immersive Accessibility (ImAc) project identified the requirement for voice control as part of the projects

fully accessible 360o video player in order to be fully accessible to people with sight loss. An assessment of

speech recognition and voice control options was made. It was decided to use an Amazon Echo with a node.js

gateway to control the player through a web-socket API. This proved popular with users despite problems

caused by the learning stage in the command structure required for Alexa, the timeout on the Echo and the

difficulty of working with Alexa whilst wearing headphones. The web gateway proved to be a robust control

mechanism which lends itself to being extended in various ways.

1 INTRODUCTION

Immersive media technologies like Virtual Reality

(VR) and 360º videos are increasingly present in our

society and its potential has put them in the spotlight

of both the scientific community and the industry.

The great opportunities that VR can provide not only

in the entertainment sector, but also in

communication, learning, arts and culture has led to

its expansion to more audience (Montagud et al

2020). These technologies are gaining popularity due

to the COVID-19 crisis as they enable interactive,

hyper-personalized and engaging experiences

anytime and anywhere.

360º videos are gaining popularity as they are a

cheap and effective way to provide VR experiences.

They use specialized multi-cameras equipment that

can capture a 360º x 180º field of view instead of the

limited viewpoint of a standard video recording.

Moreover real scenarios and characters can be

directly captured with a 360º camera. 360º video can

be enjoyed both via traditional devices (PC, laptops,

smartphones) or VR devices (Head Mounted

Displays, HMDs).

As for every media content, 360º media experien-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4468-6660

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1613-915X

ces need to be accessible. Typically, accessibility has

been considered in the media sector as an

afterthought, despite many voices asking for the

inclusion of accessibility in the creation process

(Romero-Fresco 2013). Audio-visual Translation

(AVT) and more specifically Media Accessibility

(MA) (Remael et al. 2014; Greco 2016), is the field

in which research on access to audio-visual content

has been carried out in the last years, generally

focusing on access services such as audio description

(AD), subtitling for the deaf and hard-of-hearing

(SDH) or sign language (SL) interpreting, among

other (Agulló and Matamala 2019).

This paper focuses on the interaction with 360

o

video players. Generally users of accessibility

services already need some enhancements made to

the interface (Hughes et al. 2019), however this

becomes even more difficult once immersed in a

HMD, where there is no access to a traditional mouse,

keyboard or other controller.

The recently completed Immersive Accessibility

(ImAc) H2020 funded project focused on producing

a fully accessible 360

o

video player for immersive

environments (Montagud et al 2019). Within the

project, early focus groups identified the desirability

182

Hughes, C. and Paton, J.

Voice Interaction for Accessible Immersive Video Players.

DOI: 10.5220/0010255901820189

In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2021) - Volume 2: HUCAPP, pages

182-189

ISBN: 978-989-758-488-6

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

for voice control. The target users for these

accessibility services are generally familiar with voice

control which is starting to be used in everyday life

(Siri, Google Home, Amazon Echo) and Accessibility

users are very familiar with voice response: (Voice

Over, Talkback). In this paper we discuss the existing

technologies for voice control and present the voice

control architecture used in the ImAc project.

2 TECHNOLOGIES

Voice control effectively relies on voice recognition

algorithms (essentially voice-to-text technology).

This generally works by breaking down the audio of

a speech recording into individual sounds, analyzing

each sound, using algorithms to find the most

probable word fit in that language, and transcribing

those sounds into text.

Speech recognition has come a long way from its

first inception were early tools used simple phonetic

pattern matching algorithms running on a local PC to

modern cloud based machine learning approaches

with large training data sets.

The existing cloud based solutions to voice

recognition can be broken into 2 groups: firstly short

utterance where the user is interacting with a system

and we need to recognise one or two sentences at a

time and secondly large files where it is required to

batch process an entire audio file, such as

automatically generating a transcript from a video. In

this paper we focus on the short utterance solutions as

this is the approach that is required for voice

interaction and control.

2.1 Short Utterance

One of the most successful speech recognition tools

is the Google Cloud Speech API

3

which is available

for commercial use. Google also has separate APIs

for its Android OS and JavaScript API for Chrome. It

is also used as the basis for API.AI a tool for not only

recognising speech but also identifying intent.

Google also provides a Voice Interaction API

4

designed for interacting with personal assistance such

as the google home, or Google Assistant. Google

Voice Actions recognise many spoken and typed

3

https://cloud.google.com/speech-to-text/docs/apis

4

https://developers.google.com/voice-actions/interaction

5

https://azure.microsoft.com/en-gb/services/cognitive-

services/

6

http://www.projectoxford.ai/sdk

action requests and creates Android intents for them.

Apps like Play Music and Keep can receive these

intents and perform the requested action.

Microsoft also have a speech recognition tool -

Cognitive Services

5

which is similar to the Google

Cloud Speech API and provides the technology for

the Bing Speech API. It includes further additions

such as voice authentication. Microsoft also provide

Project Oxford

6

but only provides the core

recognition elements and so cannot be used without

additional software

Alexa Voice Service (AVS)

7

is a cloud speech-

recognition service from Amazon designed to directly

compete with Google, Apple and Microsoft. It is used

as the backbone to Amazon’s Echo which in turn is a

competitor to the Google Home and Apples Siri.

Other tools such as Wit.ai

8

are designed to allow

developers to seamlessly integrate intelligent voice

command systems into their products and to create

consumer-friendly voice-enabled user interfaces.

IBM Watson (Kelly 2013) is a powerful tool for

machine learning and analytics. It focuses on

analysing and structuring data and has speech-to-text

and text-to-speech solutions. It is designed for big

data analysis, but it is not designed for speech

interaction.

The Web Speech API

9

aims to enable web

developers to provide, in a web browser, speech-input

and text-to-speech output features that are typically

not available when using standard speech-recognition

or screen-reader software. The API itself is agnostic

of the underlying speech recognition and synthesis

implementation and can support both server-based

and client-based/embedded recognition and

synthesis. The API is designed to enable both brief

(one-shot) speech input and continuous speech input.

Speech recognition results are provided to the web

page as a list of hypotheses, along with other relevant

information for each hypothesis. It is part of the W3C

spec, meaning that although compatibility is still

limited, it should become standard.

Annyang

10

, provides an API built on top of the

Web Speech API, specifically designed for filtering

and recognising commands, rather than all text. It

supports all of the relevant languages and in our

simple tests have found it to be very successful in

both continuous and push to talk configurations.

7

https://developer.amazon.com/en-US/docs/alexa/alexa-

voice-service/get-started-with-alexa-voice-service.html

8

https://wit.ai/

9

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/

Web_Speech_API

10

https://www.talater.com/annyang/

Voice Interaction for Accessible Immersive Video Players

183

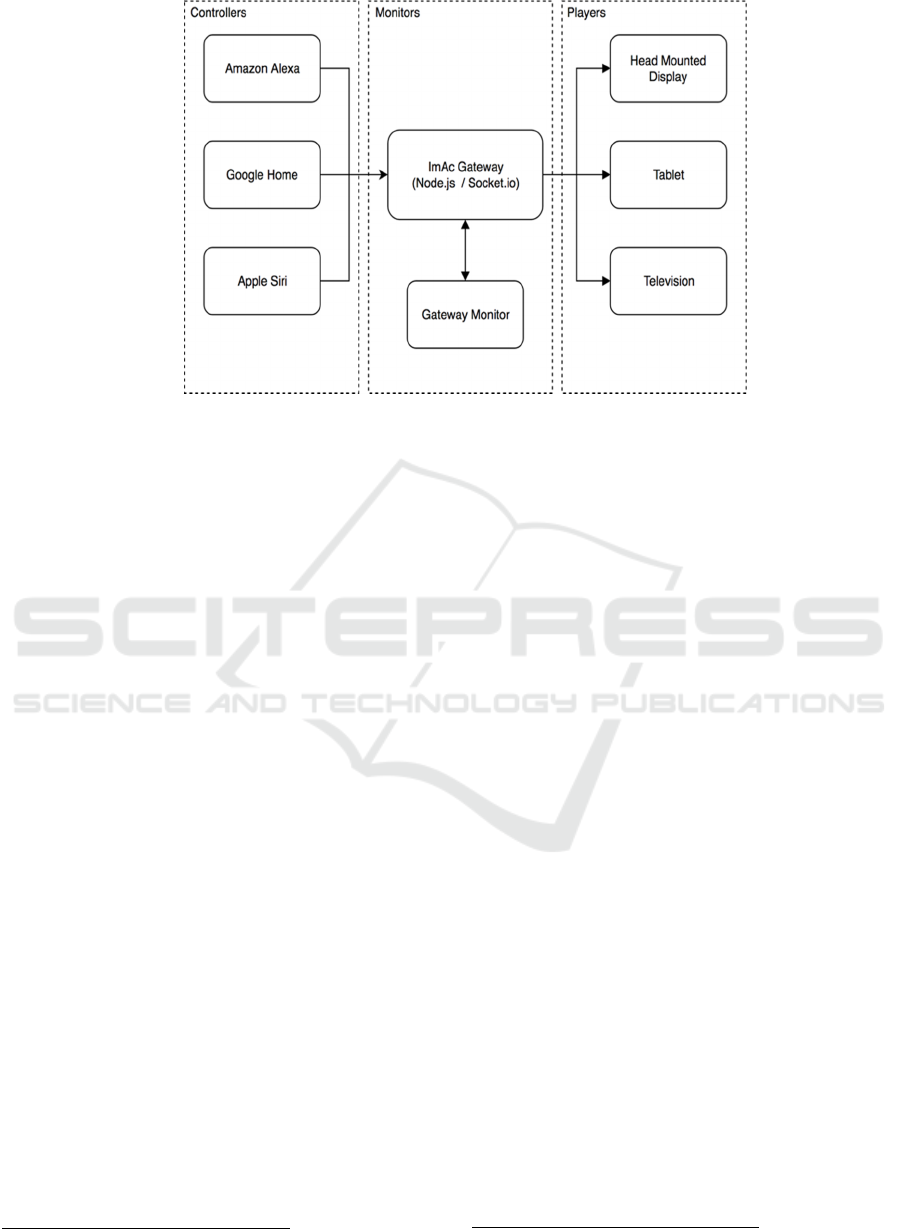

Figure 1: The gateway architecture for the voice control interface to the ImAc Player.

There are also tools designed for handling voice

recognition offline. These are useful in situations

where no internet is available, or unreliable coverage.

For example CMU Sphinx (Lamere et al., 2003) is a

Speech Recognition Toolkit which due to low

resource requirements can be used on mobile devices

with no network connection.

3 VOICE CONTROL SERVICE

Within the ImAc player it was desirable that users

should be able to use the technology devices that they

already owned and from our survey we established

that online short utterance services where most

reliable, especially those services designed for voice

interaction, such as the Amazon Echo, Google Home

or Siri. Each of these devices are commonly used by

accessibility users and use logic to understand the

user's request. For example if they don't understand

the first time what the user is asking, will ask them to

repeat it or make suggestions. At the time of

development the Amazon Echo was provided with the

most advanced API and that it would be used for the

main interface for testing during the project, however

our architecture was designed to provide a basic

interface to the ImAc player, which could easily be

extended by adding new devices as they become

available.

All of these solutions utilize external cloud based

service to perform the voice recognition, rather than

being processed locally. This means that in order to

11

https://nodejs.org

integrate with the player an intermediate ‘gateway’

was implemented in order to receive the commands

from the cloud and forward it via a web socket to the

player.

3.1 Gateway

In order to pass commands from voice control devices

a gateway has been implemented. This allows for a

generic mechanism for connecting new devices,

which simply need to connect to a web socket and

pass a standard command. The gateway is built using

node.js

11

and socket.io

12

in order to provide a

persistent service. Every device utilizing the gateway

is registered on its first connection and a web socket

is maintained for each device as shown in Figure 1.

Within the gateway there are three types of

‘device’, which can connect to the gateway:

1. Controllers – Any device which issues

commands

2. Players – Any device which consumes

commands

3. Monitors – Any device which consumes

all communications for testing and

monitoring

Each device uses a specific identifier (ID), which

matches the controllers to the player. During our

study this ID was set to the serial number of the

device which could be returned from the device API.

By design a player with a specific ID will only receive

commands from controllers with the same ID. This

means that there can be multiple players and

12

https://socket.io/

HUCAPP 2021 - 5th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

184

controllers using the gateway, but only those with the

same ID will talk to each other. It is also possible to

connect multiple controllers to a single player by

registering the same ID.

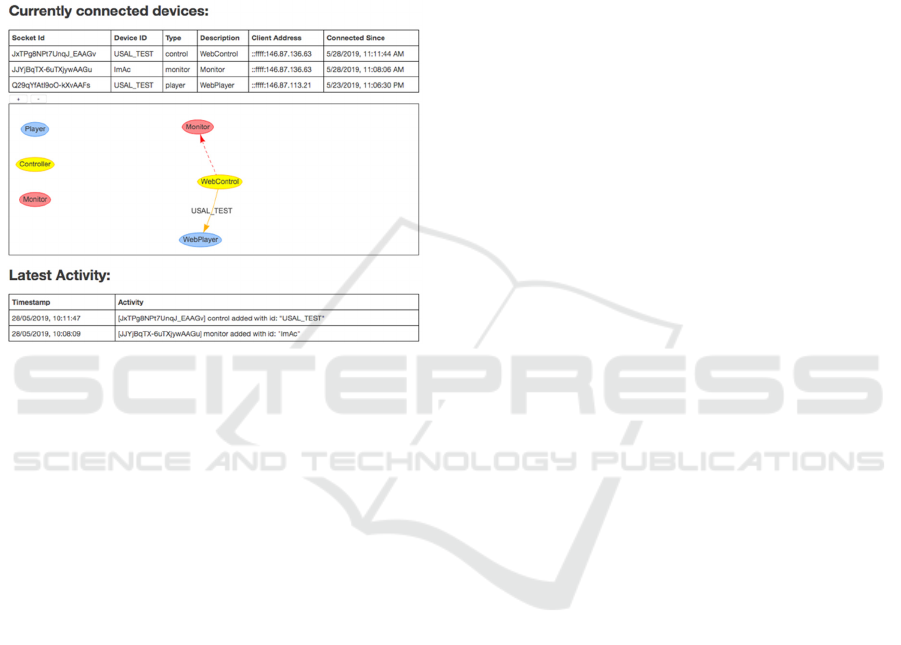

We also provide a monitor that can be connected

to the gateway through a web browser which shows

the overall status of the server and provides a real

time network diagram of each of the connected

devices and the flow of information, as shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2: The monitor view for the voice control gateway.

Within the monitor you can identify the current

connections to the gateway including each of the

connected players, controllers and other monitor

pages that are currently open. A log of Latest Activity

shows the every activity that the server has performed

since you opened the page. This includes devices

connecting and disconnecting as well as commands

being sent.

The monitor also contains links to two other web

tools, which replicate both a virtual controller and

virtual player. Opening either of these will ask for the

user to specify the device ID and then simulate either

a controller or a player. These are really useful while

testing as the virtual controller / player allows you to

match the ID to an existing device in order to fully

test the interface.

The gateway is open source and available from

https://github.com/chris-j-hughes/ImAc-gateway

3.2 Voice Control Interface

In order to identify each of the controllers the device's

internal serial number is used as a unique identifier.

This unique identifier is then used when connecting

to the gateway, and used to direct any commands

from the device to the registered player.

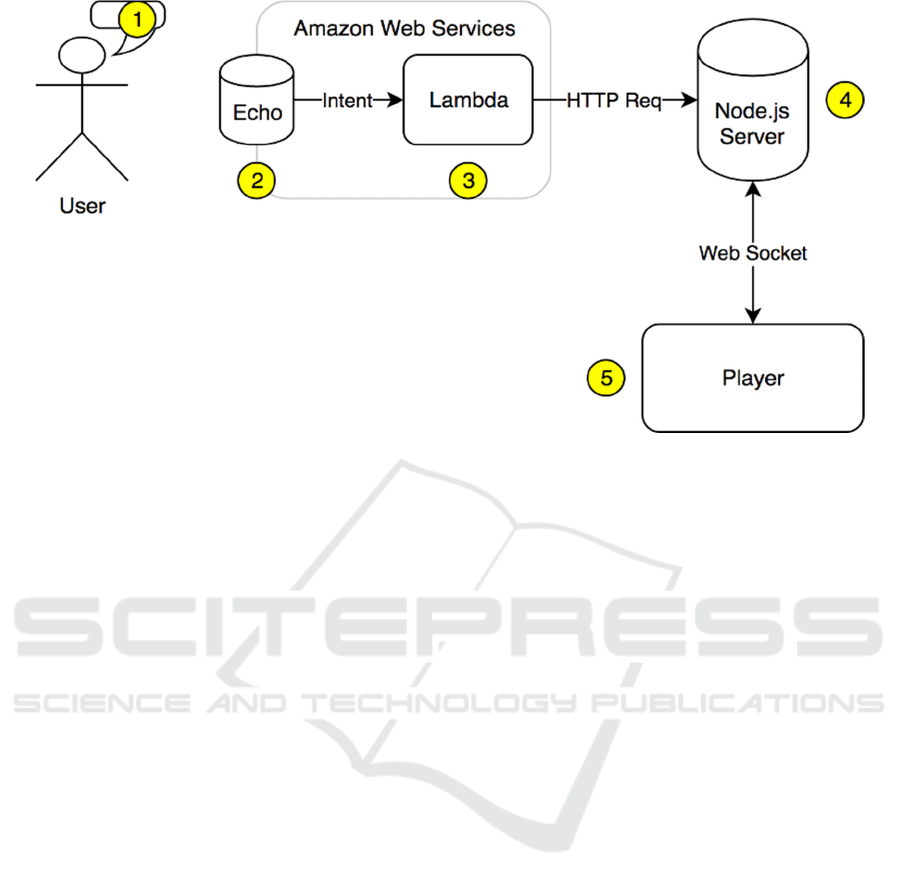

The basic workflow for the Amazon Echo

integration is shown in figure 3:

1. The User

The user issues commands to Alexa. An application

built for Alexa is referred to as a ‘skill’ and you begin

interacting with a skill either by issuing the command

‘[Wake Word] open [skill invocation name] and

issuing commands or by saying ‘[Wake Word] ask

[skill invocation name] to [command].

One key limitation we identified of using the Amazon

Echo is that once you open a skill, the device only

listens for a short time for security reasons and to

prevent it recording personal conversations that you

are not expecting. This can cause confusion as it is

therefore required to wake the device before asking

each command. We extended the skill to utilize

CanFulfillIntentRequest which allows for Name-free

Interactions. This meant that the commands became

standardized into the format “Alexa ask [device] to

[request]” removing the need to wake the device

separately. It also became apparent that users could

judge how long the echo device listened for if they

were issuing a series of commands. In order to assist

further, the gateway provides a listening and

stopped_listening command to the player to enable

this to be represented visually in the users viewpoint.

2. The Echo

The Alexa skills are built within the Amazon Web

services framework (developer.amazon.com). Each

skill contains a number of ‘Intents’ where each

‘Intent’ is designed to trigger a specific event,

however there may be multiple phrases that could be

used to derive the same action. Variables such as

numbers can also be defined within intent.

The intents are each defined with a unique name,

and a set of sample phrases which could be used to

trigger them, for example our simple play command

can be implemented to look for the play command

and invoked the playVideoIntent:

{

"name": "playVideoIntent",

"slots": [],

"samples": [

"play"

]

},

If it is required to capture a variable, such as a

number, the slots can be defined as a wildcard for

where the values would go, such as our command for

changing the subtitle size:

Voice Interaction for Accessible Immersive Video Players

185

Figure 3: The basic workflow for the amazon Echo example.

"name": "subsSizeIntent",

"slots": [

{

"name": "subSize",

"type": "AMAZON.NUMBER"

}

],

"samples": [

"change subtitle size to {subSize}",

"set subtitle size {subSize}",

" subtitle size {subSize}"

]

3. AWS Lambda

The identified intent name is posted to Lambda. This

is an Amazon Web Services (AWS) application

which allows you to run JavaScript code in the cloud

without the need for a server and the preferred way to

process commands from the Amazon Echo device.

This provides a bridge between each intent from the

Echo and our gateway. It also formulated a response,

which is the spoken response provided to the User.The

command is pushed to our gateway by sending an

HTTP POST request with the current intent.

4. The Gateway

The gateway is a node.js server which manages all of

the clients and forwards the incoming intent to any

client with the same identifier through the previously

connected WebSocket.

5. Player

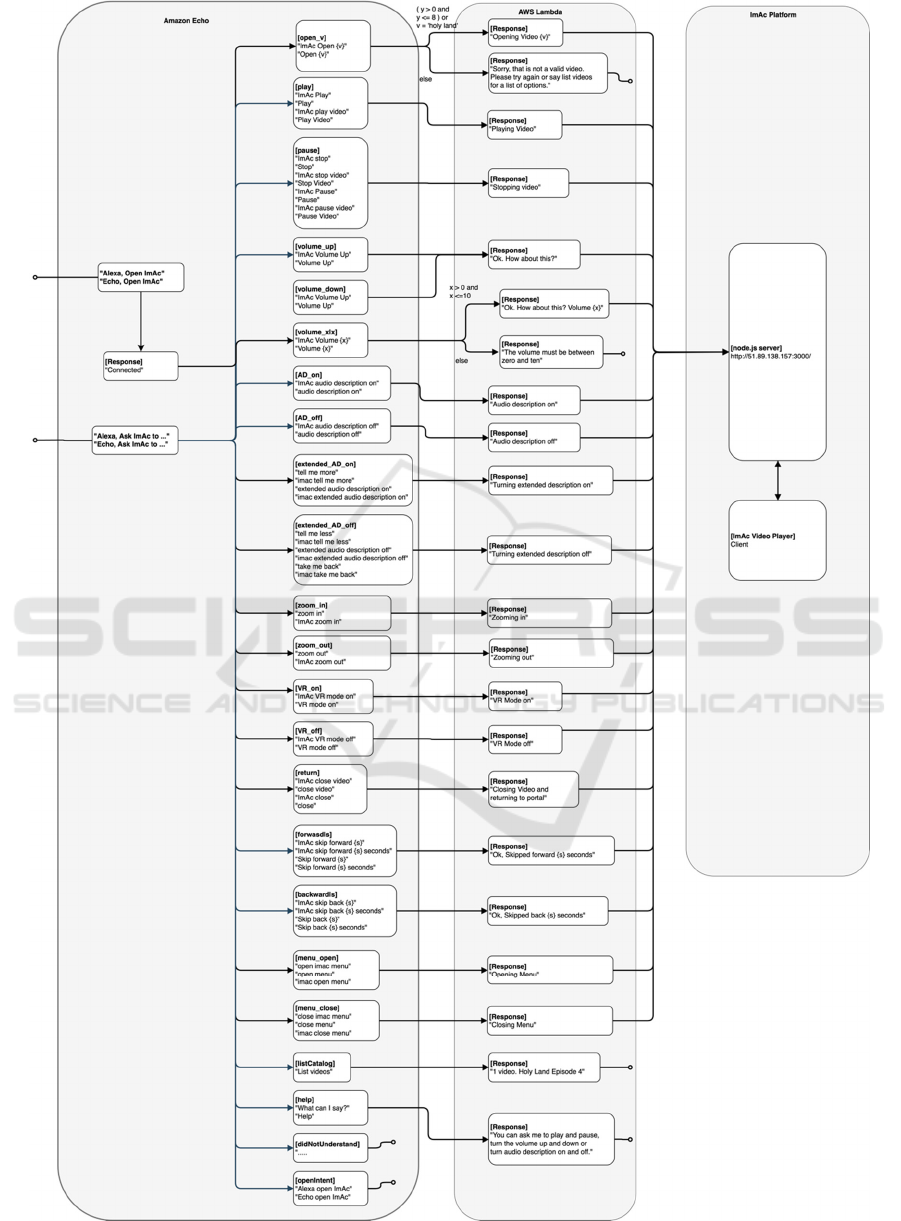

The player receives each intent and interprets it as an

action During testing the default set of commands is

defined in figure 4. didnotunderstand is used as a

generic catch all for if a command is issued but not

identified and allows for the gateway to respond

appropriately.

3.3 Pairing, Authentication and

Security

An additional intent, built into the Alexa skill is ‘what

is your ID’. When invoked it forces the device to read

out its defined ID. In the player you can enable Voice

control from the menu. This is listed under ‘General

Settings’-> ‘Voice Control’. When you turn it on it

will ask for an ID, as shown in figure 5. This is the ID

that it is listening to.

The player will also remember this ID and setting

using browser cookies. Once connected and enabled

the player uses web sockets to connect to the gateway

and will then appear in the gateway-monitor.

It is also possible to connect more than one player

to the gateway if you choose, such as one on a HMD

and another in a browser and they will receive the

same commands. This is particularly useful if you

wish to replicate what a user can see on their head

mounted display on a second computer.

Although it would be remarkably difficult to

guess a device serial number, in a real world

deployment there is a security risk that you could take

control of another user's device. However you could

never access their voice, or personal information. It

was therefore concluded secure enough for a pilot

study, however moving forwards Two-Factor

authentication would be recommended.

HUCAPP 2021 - 5th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

186

Figure 4: The default intent path used during the pilot study.

Voice Interaction for Accessible Immersive Video Players

187

Figure 5: The voice control menu in the ImAc Player.

4 RESULTS

A full pilot study was conducted as part of the ImAc

project. Connecting the player and Amazon Echos to

the gateway went well and was exactly as planned.

The gateway infrastructure also enabled the

commands to be translated into additional languages

(Spanish, Catalan, German, French) by simply

providing additional sample sets within the skill.

In the pilot action, blind and partially sighted

people were asked to wear earphones to hear the

output of the media player and to use their voice to

control the player via an Amazon Echo. After being

told the list of commands they were asked to perform

standard operations such as starting the video,

stopping the video, skipping forwards and backwards

in the video, adjusting the volume and turning audio

description on and off.

Users in the pilot were very keen on the idea of

controlling the player through their voice and by

using the Echo. Most expressed a level of familiarity

with voice control interfaces including Amazon Echo

and Google Home. Anecdotal evidence also suggests

the use of voice assistants in smartphones will have

increased familiarity with voice control mechanisms

among people with sight loss.

However some users also expressed frustration

with the voice control interface. Headphones were

required to listen to the content which was a binaural

rendering of a 360 degree soundscape. Users

however, found they blocked the audio feedback from

the Echo. This led to one user commenting that they

didn’t want to be “...screaming over the content only

so the Echo can hear me.”. Another user uncovered

one ear so they could hear both the media content and

Alexa.

The indicators showing whether the Echo was

still listening are visual, meaning that users often

didn’t realise they would need the wake-word again.

This caused some difficulties as users would say

“Alexa Open ImAc” hear the response “connected”

and then try to issue a few commands to test the

interface.

Any commands issued after the timeout would be

ignored leading the user to keep trying before using

the “Alexa Open ImAc” command again.

Users could also use a one-part command

structure for instance “Alexa, Ask ImAc to skip

forward five seconds”. Users expressed frustration at

needing to use specific commands whilst

acknowledging that this was down to the Alexa

service rather than the ImAc player. Users requested

a more conversational command structure and for the

voice commands to be integrated into the media

player itself.

Despite the various frustrations users reported

that the system was easy to use and some users

offered to test it again if the issues raised were

addressed.

Most users also expressed an interest in using

other control mechanisms such as gestures and swipes

on a mobile phone app or physical buttons or a

joystick.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Users rated the voice control as easy to use despite

frustrations with Alexa timing out and being unable

to hear Alexa’s responses. This may suggest either a

strong appetite for voice control in devices, a strong

desire for alternative control mechanisms to those

commonly experienced in other media players or an

eagerness to please researchers. The high level of

stated familiarity with voice control interfaces may

suggest this is a popular control mechanism and there

is an appetite for more voice control.

For a blind and partially sighted audience who are

unable to see the indication of whether Alexa was still

listening or not, using the multi-part commands (with

the first part being the “Alexa Open ImAc” preparation

command) did not work well. Nor did audible feedback

coming from the Echo while the users were using

headphones to listen to content. Creating a second

channel of audio feedback through the media player to

mirror Alexa’s responses (including an indication that

the timeout would have expired) may have solved this

but was out of scope in this project.

All of the frustrations were caused by the choice

of control mechanism. The architecture linking the

Echo to the media player was robust and enables other

control interfaces to be considered and connected.

HUCAPP 2021 - 5th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

188

Users spontaneously suggested gesture controls and a

remote control built into a smartphone app could give

immediate and familiar controls to smartphone users.

Since the gateway could accept multiple input

mechanisms for a media player a smartphone app

receiving gesture controls could connect at the same

time as Alexa. This would enable media discovery

commands (such as “Alexa, Ask ImAc to list

content”) which are suited to a voice control interface

to go through Alexa and media control inputs (such

as play, pause, skip forward, skip backward) to come

from a smartphone app or remote control.

Using a gateway architecture enables an

abstraction layer to allow personalised control

interfaces or access technology to be used without the

media player needing to be aware of the precise

control mechanism. This includes but is not limited to

joystick control, sip-and-puff systems, eye gaze,

single-button interfaces, sign language or basic

manual gestures or even EEGs (brainwave detection).

It also enables future technologies to be developed

and used to control a media player which has no

knowledge of them.

This abstraction layer also provides other options.

Compound controls could use a single input

trigger from the user to command multiple devices.

This could mean when the main content is played

lights are dimmed, phones put on mute and access

services could be downloaded and streamed

synchronously from a companion device.

Machine to machine interactions could allow

trusted devices such as phones or doorbells to pause

the main content.

Interpreted commands could enable people to

watch content personalised to them. Access services

(such as subtitles or AD) could be always enabled or

disabled depending on the user, access controls (such

as age restrictions) could be put in place or which

device the output is shown on could depend on which

is closest or the user preference (TV, tablet or VR

headset).

The idea of such an abstraction layer is in line

with work being done at the W3C to enable a Web of

Things (WOT)

13

. A Thing Description (TD)

14

which

detailed the API of the media player would be

published either by the media player or by the

gateway on its behalf. Authenticated WOT aware

controllers or device chains could then send

commands to the media player via the gateway. The

gateway and media player do not need to know where

the command originated or how, only that the

command is valid and authorised.

13

https://www.w3.org/WoT/

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been conducted as part of the ImAc

project, which has received funding from the

European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and

innovation programme under grant agreement

761974.

REFERENCES

Agulló B, Montagud M, Fraile I (2019). Making interaction

with virtual reality accessible: rendering and guiding

methods for subtitles. AI EDAM (Artificial Intelligence

for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing)

doi: 10.1017/S0890060419000362

Agulló B, Matamala A (2019) The challenge of subtitling

for the deaf and hard-of-hearing in immersive

environments: results from a focus group. The Journal

of Specialised Translation 32, 217–235

http://www.jostrans.org/issue32/art_agullo.php

Greco, G. (2016). “On Accessibility as a Human Right,

with an Application to Media Accessibility.” Anna

Matamala and Pilar Orero (eds) (2016). Researching

Audio Description New Approaches. London: Palgrave

Macmillan, 11-33.

Hughes, CJ, M. Montagud, Peter tho Pesch.(2019)

“Disruptive Approaches for Subtitling in Immersive

Environments.” Proceedings of the 2019 ACM

International Conference on Interactive Experiences for

TV and Online Video – TVX ’19.

10.1145/3317697.3325123

Kelly, J.E. and Hamm, S. ( 2013). Smart Machines: IBM's

Watson and the Era of Cognitive Computing. Columbia

Business School Publishing

Lamere, P., Kwok, P., Gouvêa, E.,Raj, B., Singh, R.

Walker, W., Warmuth, M. and Wolf, P. (2003) “The

CMU SPHINX-4 Speech Recognition System"

Montagud, M., I. Fraile, E. Meyerson, M. Genís, and S.

Fernández (2019). “ImAc Player: Enabling a

Personalized Consumption of Accessible Immersive

Content“. ACM TVX 2019, June, Manchester (UK)

Montagud, M., Orero, P. and Matamala, A. (2020) "Culture

4 all: accessibility-enabled cultural experiences through

immersive VR360 content". Personal and Ubiquitous

Computing: 1-19

Remael, A., Orero, P. and Mary C. (eds) (2014).

Audiovisual Translation and Media Accessibility at the

Crossroads. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi.

Romero-Fresco, P. (2013) “Accessible filmmaking: Joining

the dots between audiovisual translation, accessibility

and filmmaking.” The Journal of the Specialised

Translation 20, 201-223.

14

https://www.w3.org/TR/wot-thing-description/

Voice Interaction for Accessible Immersive Video Players

189