AI for Future Mobility: What Amount of Willingness to Change Does

a Society Need?

Gesa Horn and Kathrin Schönefeld

Chair of Technology and Management of Digital Transformation,

Bergische Universität Wuppertal, Gaußstraße 20, 42119 Wuppertal, Germany

Keywords: Smart Mobility Concepts, Willingness to Change, Acceptance, Holistic Approach, Interdisciplinary Research.

Abstract: In addition to demographic changes in society, the success of modern forms of mobility such as automated

vehicles and new mobility models is increasingly contingent on the acceptance by users from the local

community. Various factors influence acceptance and the related concepts of willingness or resistance to

change. A distinction can be made between general and specific willingness to change. General willingness

to change is an attitude of users towards innovations, whereas specific willingness to change is situation-

specific and relates solely to a specific change and its process. In the project Rethinking Mobility at the

University of Wuppertal (Bergische Universität Wuppertal), the question is investigated of how to overcome

resistance, enhance acceptance towards new mobility concepts and how the best basis can be created for users

to form individual’s opinion on future mobility concepts. In addition, users should be enabled to perceive the

advantages of new solutions and to compare them with their own values and standards. From the project's

point of view, a holistic view of the complex topic of technically assisted forms of mobility is crucial for the

implementation of new mobility concepts. In particular, the advantages of the integration of artificial

intelligence (AI) will be examined in the project.

1 INTRODUCTION

The cities of Wuppertal, Solingen and Remscheid

form the Bergisch City Triangle (Bergisches

Städtedreieck) and are faced with large altitude

differences within and between the three urban areas.

Between the lowest and the highest area in the

Bergisch City Triangle there are 325 meters of

altitude difference. All three urban areas differ in

altitude more than 200 m. Within the city limits of

Remscheid, the difference is even more than 280 m

(bgmr, 2020). This results in many meters in altitude

that citizens and visitors of the Bergisch City Triangle

have to cover on their way through the region. Almost

200,000 people commute to or from one of the three

cities every day (IT.NRW, 2017). Combined with the

85% of the citizens of the Bergisch City Triangle that

use mobility solutions on a daily basis, a huge number

of people move within the region every day (Nobis,

Kuhnimhof, Follmer, & Bäumer, 2019). These people

need mobility possibilities that meet their needs under

the given circumstances and make their journey as

pleasant as possible. In addition to the special features

of the Bergisch City Triangle mentioned, megatrends

such as demographic change and urbanization occur

as well. For the cities of the Bergisch City Triangle,

as for Germany as a whole, it is predicted that the

average age of the population will increasingly rise in

the coming years. This will change the needs and

requirements for mobility solutions in the future.

Next to this, many cities in Germany are faced with

an increasing number of mobility users. Based on

this, a mobility concept that adapts the needs of all

user is becoming increasingly necessary. Successful

mobility concepts of other major German cities such

as Cologne or Munich cannot be transferred to the

Bergisch City Triangle without further ado. The

spatial and socio-spatial conditions of a city have a

direct influence on the acceptance or rejection of new

mobility options by its citizens. Similar to companies,

culture and history have a considerable influence on

the reaction of citizens. As an example, offers like

bike sharing, which are highly accepted in cities with

a long-standing cycling culture such as Münster,

Bremen or Karlsruhe, cannot be transferred to cities

with a different cycling culture. In future mobility

concepts, the region of the Bergisch City Triangle

must be considered as a whole and yet in its

38

Horn, G. and Schönefeld, K.

AI for Future Mobility: What Amount of Willingness to Change Does a Society Need?.

DOI: 10.5220/0009577500380043

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2020), pages 38-43

ISBN: 978-989-758-418-3

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

uniqueness in order to find ideal solutions for existing

challenges and circumstances. Furthermore, for a

successful introduction of new mobility concepts it is

crucial to satisfy the users’ needs of mobility. It is

important to detect and define specific factors that

influence someone’s willingness to change to enable

the modernization of the mobility concept of the

Bergisch City Triangle. The willingness to change is

one of the crucial factors to increase the acceptance

for innovations within the whole society of the region.

The connection between acceptance and willingness

to change as well as the importance of both concepts

for the success of future mobility in the Bergisch City

Triangle is explained in the following. Next to this the

reasons why the citizens’ acceptance and the early

involvement of society are decisive criterions for a

successful introduction and conversion of new

mobility concepts will be discussed. To understand

the challenge for a change on short notice insights in

the environmental key characteristics in times of

digital transformation and industry 4.0 are given next.

2 ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT

People tend to assume that people know how other

people will behave in a given situation. The

assumption that people’s behavior is that easy to

understand leads to the persuasion that technical

systems and machines can easily replicate human

behavior. This hypothesis is not tenable, since human

behavior is only rarely that unambiguous that it can

be predicted correctly. With regard to the needs of

potential users, it is often concluded that some people

can formulate their own needs and generalized the

results to the entire urban population. This

presumption implies the risk that core needs of

potential users will not be considered and that new

mobility concepts will not be adopted because they

miss out on the users' needs. Especially in technical

areas, it is frequently expected that innovations which

can objectively be perceived as useful and technically

well implemented will be accepted by users as soon

as the technical improvement over existing offers is

recognized and the advantages are properly

explained. The reasons why this approach is not

sufficient to explain human behavior in its entirety are

discussed in the following subchapter.

2.1 Human Behavior

In order to understand how people deal with

innovations and environmental changes, it is

important to understand what constitutes and affects

human behavior. The unique aspect of humans

compared to existing robots and machines is that

humans can behave differently under similar

conditions. Machines and robots have an inhuman

and sometimes frightening effect on humans due to

their "perfect" reactions. Human behavior is diverse

and has complex causes that can be traced back to the

interaction of various factors. Therefore, it is difficult

to predict human behavior with any certainty. Human

behavior is not driven by reflexes and drives and can

rarely be replicated. Reactions to the same

environmental conditions can be completely different

from one time to another, since human behavior is the

result of the interaction of numerous internal and

external factors. Factors such as previous experiences

and mood affect type and extent of behavior. In

addition, factors such as group dynamics,

environmental factors and individual personality

traits have a considerable influence on human

behavior (Freyth, 2017). Events that appear to be

unrelated to the actual situation can fundamentally

influence a person's judgement and consequently

their reaction (Williams & Bargh, 2008).

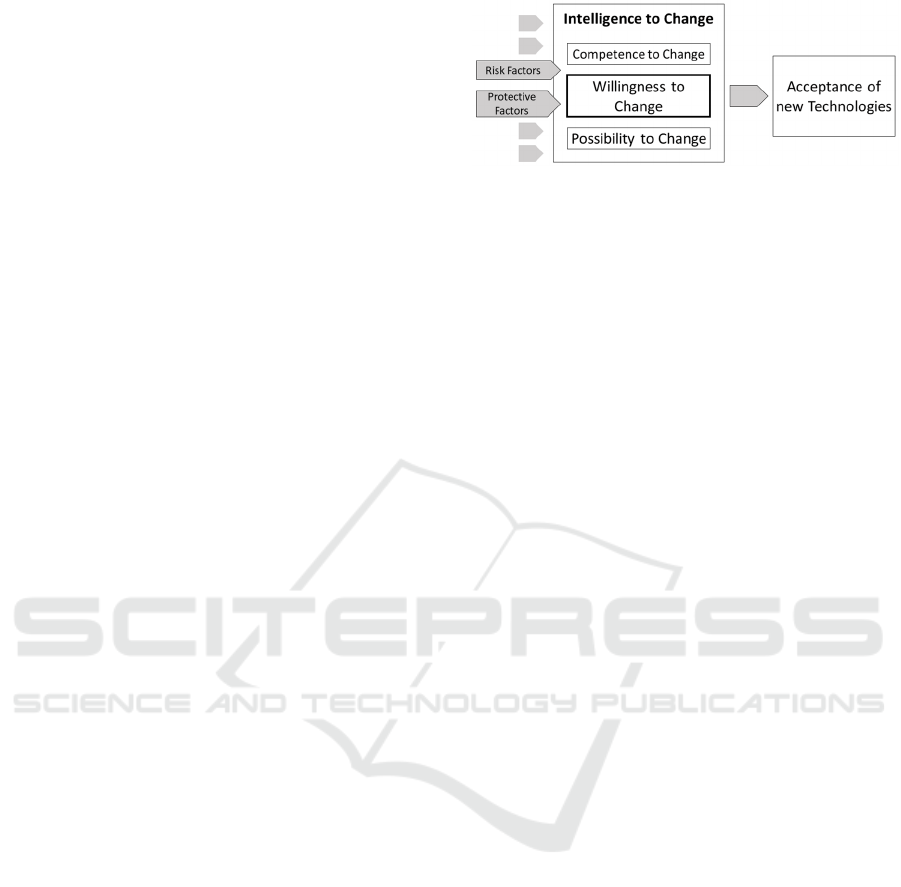

A characteristic that builds the foundation for

acceptance of environmental changes, such as the

preferred type of mobility, is willingness to change.

Willingness to change is, next to competence to

change and possibility to change, an element of the

individual intelligence to change. intelligence to

change refers to the ability of a person to adapt to

changing circumstances. Among intelligence to

change, willingness to change defines, the

individual's readiness to accept change and to

embrace innovations (Baltes & Freyth, 2017). This

does not mean that a person unconditionally accepts

and integrates innovative alternatives into his or her

everyday life but rather that the person is generally

convinced that using the new alternatives is a

possibility (Baltes & Freyth, 2017). The degree and

access to one’s personal willingness to change

depends on the situation and can vary significantly

according to environmental conditions.

Direct and moderating factors of willingness to

change can be distinguished in risk and protective

factors. On one hand, risk factors are factors that

potentially weaken the willingness to change.

Protective factors, on the other hand, are factors that

enhance willingness to change and create ideal

circumstances for a person to be open to change and

new experiences. Risk and protective factors can

further be divided into biological, psychological and

social factors. All relevant factors are directly or

indirectly related to the shown behavior and influence

its occurrence either positively or negatively. In

AI for Future Mobility: What Amount of Willingness to Change Does a Society Need?

39

addition to risk and protective factors, there are also

neutral factors that have no influence on willingness

to change or situation-related behavior (Figure 1).

Within the context of mobility, risk and protective

factors of potential users' willingness to change can

be defined. Risk factors are the factors that hinder or

negatively influence openness towards new mobility

concepts. Protective factors favor and promote

acceptance in mobility context. Freyth (2017)

identifies several factors that generally foster

openness to new ideas regardless of the current

situation, namely the general willingness to change.

These factors include traits such as curiosity,

optimism, frustration tolerance and risk affinity.

Willingness to change is a trait that is rather

consistent over time due to its connection to the Big

Five personality traits and can be trained or

encouraged within a biologically predetermined

extent (Freyth (2017).

It is a time-consuming and divided process to

define which factors are crucial to encourage both

general and specific willingness to change. Specific

willingness to change is situation-related. This type

of willingness to change is connected but does not

depend on one’s general willingness to change. In

order to increase the specific willingness to change, it

is important that the need for change is transparent

and plausible for the individual. Unless the reasons

for the present situation cannot be maintained are

communicated sufficiently, it is difficult even for

people with a strong general willingness to change to

be open to change. The advancement of willingness

to change is an interaction of general and specific

willingness to change (Freyth, 2017).

At present no studies on a universal understanding

of acceptance factors for future mobility innovations

have been published. Particular applications have

been examined and the acceptance of these

technologies have been surveyed. A comprehensive

presentation regarding the acceptance of entire

mobility concepts including hard and soft facts has

not yet been established. One reason for this shortage

might be the fact that very few cities began to

implement a fully integrated smart mobility concept

yet. With regard to the improvement of acceptance,

willingness to change is mentioned as a fundamental

criterion in the organizational field. In the

organizational context a high willingness to change

among employees is a key factor for the company’s

success, as willingness to change is closely linked to

innovation orientation (Franklin & Krüger, 2017).

For a continuous competitiveness it is essential for

companies to manage change and to explore

innovations.

In order for this to work successfully at

Figure 1: Factors of Willingness to Change

an increasingly rapid pace, an early and long-term

review of the risk and protective factors of

willingness to change is essential for the success of a

change process.

Since there are no studies on willingness to

change in the mobility sector yet, it is questionable to

what extent connections can be transferred from an

organizational context to a mobility context. Studies

on acceptance of mobility concepts can be built upon

findings from organizational research and evolve

from there. Specific conditions that have to be

considered for research on acceptance and

willingness to change in the mobility sector of the

Bergisch City Triangle will be explained in the

following.

2.2 Mobility Revolution

For a revolution of current mobility systems, a

holistically designed model that is available at short

notice is crucial in order to keep track of and act to

global technology development, to achieve climate

goals and at the same time to meet the citizens' needs.

Cities and city councils have a major advantage in

achieving their set goals if citizens are open to new

forms of mobility and are keen to explore new offers.

This is the only way to counteract the trend of rising

car numbers and the resulting increase in traffic jams

in most city centers. Openness to mobility changes

can be optimized and supported by targeting the

greatest possible willingness to change of citizens

when implementing new mobility offers and

formulating them accordingly.

Based on the assumption that the distribution of

willingness to change among mobility users shows a

similar distribution as innovation projects it can be

assumed that ⅙ of all users show a high willingness

to change and are very curious about new possibilities

(Rogers, 1962). According to Rogers' diffusion

theory (1962) it can be assumed that ⅙ of potential

users will seldom or even never interact with new

possibilities as long as the innovation is new and

unfamiliar. They start to use an innovation if the

product or process is fully integrated into the

everyday life. On the remaining 66 % risk and

SMARTGREENS 2020 - 9th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

40

protective factors have a crucial impact. In addition to

previous personal experience and the general

willingness to change, the way to address innovations

and convey information is critical to the acceptance

of all kind of innovations (Freyth, 2017).

To increase willingness to change it is crucial to

communicate the necessity of (behavioral) change in

a comprehensible way. In mobility context concerns

and fears of users need to be considered. In addition,

disadvantages of the current mobility solutions

should be communicated transparently. To actively

shape the future of mobility in cooperation with

potential users, a change of faith among potential

users should be initiated, and a process of rethinking

initiated. A project of the University of Wuppertal

investigates how acceptance of new mobility

concepts are distributed among citizens of the

Bergisch City Triangle and which factors have a

positive or a negative effect on the acceptance of a

general and inclusive mobility solution.

3 RETHINKING MOBILITY

Defining the possibilities of artificial intelligence

(AI) within the mobility revolution and a sustainable

development of new forms of mobility is a major goal

of modern mobility concepts of the Bergisch City

Triangle for the next years. The cities of Wuppertal,

Remscheid and Solingen are cooperating with local

transport companies, an economic development

agency, an automotive supplier and the University of

Wuppertal on a certain real-life laboratory project

called Bergisch.Smart_Mobility. Funded by the

Ministry of Economic Affairs, Innovation,

Digitalisation and Energy of NRW in Germany the

project Bergisch.Smart_Mobility aims to implement

AI as an enabler of future mobility until the end of

2021.

Four subprojects have been defined within the

larger project Bergisch.Smart_Mobility that deal with

different perspectives and methods on artificial

intelligence as enabler for the future of mobility. The

subprojects conduct on one hand insights in technical

future topics such as Smart Vehicle Architecture, On-

Demand Services and AI-based Traffic Management.

On the other hand, in the project Rethinking Mobility

an integrated approach to modernize forms of

mobility in the Bergisch City Triangle in a sustainable

manner and the development of holistic solutions is

researched. The latter is the foundation of the planned

research of users’ acceptance and resistance. A more

detailed insight into the objectives and methods of

Rethinking Mobility as well as the projects structure

will be given in the following sections.

3.1 Project Objectives

The goal of artificial intelligence as an enabler for

future mobility is closely linked to major social and

economic challenges. The ideal transport system does

not only need to be technically successful, but also

have to meet the needs and requirements of citizens

and providing companies. Furthermore, only a few

ethically relevant challenges of new mobility forms

and technologies can be solved without considered

the larger context. Even though there is a great

interest in smart mobility solutions on both sides, the

provider and the potential user, prior to

Bergisch.Smart_Mobility there were no successful

and sustainable restructured concept of a connected

mobility for the Bergisch City Triangle that combine

the various needs and interests within a holistic

solution.

An investigation on general requirements and

expectations of potential users of intelligent mobility

systems illustrates the challenge: Many citizens are

convinced that modern mobility systems are mainly

relevant for the industry and they do not see any need

for personal action. Accordingly, the willingness to

actively engage in the mobility revolution is not very

pronounced. In shaping future networked

communities and regions, the involvement and

commitment of citizens and civil society as well as

companies is particularly important. The Bergisch

City Triangle offers good structural conditions for a

joint and cooperative path into the future of mobility.

Within the framework of Rethinking Mobility, an

innovation ecosystem will be established for AI-

based mobility in the Bergisch City Triangle which

empowers citizens, qualifies skilled workers,

encourages entrepreneurs and refreshes established

educational structures.

3.2 Solution Strategy

In the context of the entire research project

Bergisch.Smart_Mobility, the subproject Rethinking

Mobility serves as a source for comprehensive

information about developments in the larger project

in a broad dialogue all significant stakeholders.

Furthermore, requirements for AI-based mobility

systems and user needs are identified as well as

economic and ecological potentials and challenges

are analyzed. In order to promote acceptance and the

implementation of new mobility concepts, factors for

the acceptance of future mobility concepts are

AI for Future Mobility: What Amount of Willingness to Change Does a Society Need?

41

identified and interpreted in the further course of the

project to generally foster acceptance. To achieve

these goals, it is important to consider the willingness

to change and other influencing factors of acceptance.

Within the subproject Rethinking Mobility two large

scientific studies will be examined to fully explore the

mechanisms underlying an increased or decreased

acceptance. Firstly, interviews will be conducted with

experts and key figures of mobility related topics. The

aim of the interviews is to define potential needs and

requirements of mobility user. Based on the results of

the interviews a quantitative survey will be conducted

to explore the actual acceptance of mobility concepts

satisfying the former defined needs. By this survey a

large number of participants will be asked to receive

results that can be generalized for the Bergisch City

Triangle. The factors that will be defined within the

survey to enhance and defend the acceptance of smart

mobility concepts will be examined in more detail.

The role of willingness to change will be explored if

necessary to answer questions regarding acceptance.

Crucial for the entire subproject Rethinking Mobility

is to involve civil society in the development of smart

solutions in order to design effects sustainable. This

interdisciplinary and integrated approach may offer

potential for receiving new insights that has not been

detected so far.

In addition to the focuses already mentioned, a

dissertation is conducted within the context of

Rethinking Mobility. The aim of the dissertation is to

develop a model that encourages the willingness to

change of the users of modern mobility solutions. The

model is expected to provide general

recommendations for introduction forms and

methods to support willingness to change with regard

to new mobility concepts. Subsequently, it should be

investigated to what extent the model can be

transferred to other regions and cities. In many

modern mobility concepts cities intensively consider

the integration of artificial intelligence. Several cities

have started first pilot projects. Among

implementations and offers of AI companies, it is

important for cities and local authorities to

consciously choose certain opportunities of artificial

intelligence in relation to their goals. Technical

solutions should not only be used because they are

available but because they fulfil a need. Local

authorities take their own decisions and accompany

the resulting development and implementation. The

first step towards intelligent mobility systems is

learning about opportunities and needs. Local

authorities, citizens and company representatives can

analyze how artificial intelligence is integrated into

other regions and the local effects of these initiatives.

At the same time, their own competences should be

applied and integrated into social discussions.

Finally, it is essential to raise awareness for the

complex challenges and opportunities arising from

the use of artificial intelligence for economy, society,

politics and science, and to guide relevant

stakeholders more closely to the subject.

By dealing with something new or unknown like

AI, personal knowledge limitations are reached by

individuals. When engaging in something unfamiliar,

personal mental order structures, for example the

degree of familiarity with a technology, are put into

perspective. Once the technology is familiar and users

trust it, users use it. In order to ensure curiosity and

interest rather than a defensive reaction,

understanding plays a special role (Schönefeld,

2016). For this reason, the main goal of the project

Rethinking Mobility is to provide information about

AI and new mobility technologies that will be

available in the future (Schönefeld, 2016). The

different participation and research formats of

Rethinking Mobility are supported by an

interdisciplinary team of experts. The project will

make a significant contribution by integrating citizens

as well as SMEs as designers and users in the

innovation ecosystem and thus to use artificial

intelligence comprehensively as an enabler for future

mobility.

4 SUMMARY

The mobility revolution is inevitable and most cities

and local authorities currently face the challenge to

develop sustainable and green mobility solutions in

the short term to fulfil the users' and providers' needs

as well as the political requirements. A

comprehensive reorientation of local authorities is

required to inform citizens about new mobility

concepts at an early stage and to involve the

community within the development process. This is

the sole way to enhance acceptance among citizens.

In order to improve the acceptance of modern

mobility solutions in the Bergisch City Triangle of

Wuppertal, Solingen and Remscheid, it is essential to

take an interdisciplinary and integrated view of the

subject area, as proposed by the project Rethinking

Mobility at the University of Wuppertal. The

substantial acceptance of innovative concepts is

appropriate as a certain number of users has to be

reached in order to sustainably implement an

innovation. If a majority of citizens accept an

innovation other people are also open to test or even

use a new technology. A city needs a society that is

SMARTGREENS 2020 - 9th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

42

open to new ideas in order to remain agile and

continuously improve the city. This can only be

enhanced when providing the best environmental

requirements for acceptance of unknown mobility

solutions.

General and specific willingness to change among

the inhabitants of the Bergisch City Triangle is one

way of externally increasing acceptance for mobility

concepts. Acceptance and willingness to change are

closely connected. The willingness to change is a key

factor in enabling prospective users to approach an

innovation as openly as possible and potentially

accept it. Mental access to the greatest possible

openness for new processes and products is linked to

the willingness to change. It is expected that

willingness to change is strengthened or encouraged

by so called protective factors and weakened by risk

factors. If these protective and risk factors are

considered during the implementation of new

mobility concepts, it can be assumed that ideal

frameworks can be defined to enable people to be as

open as possible to new ideas. Therefore, besides

increasing the awareness of the urban society and

regional companies, an aim of the project under

consideration is to identify influencing factors of

acceptance and their provision for institutions that

shape the mobility revolution for the Bergisch City

Triangle.

5 CONCLUSION

Besides the objectives of Rethinking Mobility

mentioned above, there is great potential to analyze

the origins and effects of unsuccessful mobility

concepts of recent times. Furthermore, it may

complement the project results by comparing the

recommended procedure following the Rethinking

Mobility investigations of the project with successful

mobility concepts of other cities and closely

examining its transferability. Cultural and historical

aspects may differ but the concepts could be

transferable to a certain extent. Vice versa cultural

aspect may be similar but aspects of the concepts

cannot be shared between the cities. The assumptions

of Rethinking Mobility are based on the premise that

for connected future mobility concepts some general

conclusions can be drawn about characteristics of

successful mobility concepts in Germany regardless

or with little regard to environmental factors.

Although cities need to develop individualized

approaches in order to reflect the culture and values

of an urban society, it is necessary to determine

whether certain aspects are transferable across cities

and to which extent this is feasible. Based on different

mobility strategies, it could be possible to formulate

generally valid protective and risk factors for the

acceptance of new mobility concepts. It is feasible

that factors have opposite effects in different cities.

Here a distinction needs to be explored between

stable protective and risk factors that have a general

impact for several cities, factors that change their

effects between cities and those that are neutral for

every city investigated. Finally, the transferability of

the concept developed for the Bergisch City Triangle

onto other cities needs to be investigated and

evaluated after designed within the context of

Rethinking Mobility and Bergisch.Smart_Mobility.

REFERENCES

Baltes, G., & Freyth, A. (2017). Veränderungsintelligenz.

Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

bgmr Landschaftsarchitekten, (2020). Masterplan Grünes

Städtedreieck, Bergisches Städtedreieck NRW

Retrieved from: http://www.bgmr.de/de/projekte/

MGSD_NRW

Franklin, P. & Krüger, M. (2017). Organisationale

Veränderung in internationalen Zusammenhängen. In

Veränderungsintelligenz (pp. 219-253). Springer

Gabler, Wiesbaden.

Freyth, A. (2017). Veränderungsintelligenz auf

individueller Ebene Teil 1: Persönliche

Veränderungskompetenz. In Veränderungsintelligenz

(pp. 255-321). Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden.

IT.NRW (2017). Pendlerströme der Gemeinden 2017.

Retrieved from: https://www.it.nrw/sites/default/files/

atoms/files/320b_18.pdf

Nobis, C., Kuhnimhof, T., Follmer, R., & Bäumer, M.

(2019): Mobilität in Deutschland – Zeitreihenbericht

2002 – 2008 – 2017. Studie von infas, DLR, IVT und

infas 360 im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für

Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur (FE-Nr. 70.904/15).

Bonn, Berlin. www.mobilitaet-in-deutschland.de

Rodenstock, B. (2017). Die Herausforderungen der

Veränderung im Generationenübergang meistern. In

Veränderungsintelligenz (pp. 567-609). Springer

Gabler, Wiesbaden.

Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations (1st ed.).

New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

Schönefeld, K. (2016). Auf dem Weg zum Fremden.

Virtuelles Reisen nach Neuseeland in Reportagen des

deutschen öffentlich-rechtlichen Fernsehens. Aachen

2016.

Williams, L. E., & Bargh, J. A. (2008). Experiencing

physical warmth promotes interpersonal warmth.

Science, 322(5901), 606-607.

AI for Future Mobility: What Amount of Willingness to Change Does a Society Need?

43