Modeling Semantic and Syntactic Valencies of Tibetan Verbs in the

Formal Grammar and Computer Ontology

Aleksei Dobrov

1a

, Anna Kramskova

2b

and Maria Smirnova

1c

1

Saint-Petersburg State University, Saint-Petersburg, Russia

2

Institute for Linguistic Studies, RAS, Saint-Petersburg, Russia

Keywords: Tibetan Language, Computer Ontology, Tibetan Corpus, Natural Language Processing, Corpus Linguistics,

Immediate Constituents, Tibetan Verbs, Syntactic Valencies, Semantic Valencies.

Abstract: This article presents the current results and details of modeling the Tibetan verbal system in the formal

grammar and computer ontology. The partially automated model uses an ontological editor to construct

semantic classes for verbs based on their syntactic and semantic valencies following the corpus data. The

resulting system plays a necessary pragmatic role in automatic syntactic and semantic analysis and

disambiguation of Tibetan texts. The research covers a range of problems concerning Tibetan verbal system,

such as modeling auxiliary verbs and copulas, verb compounds, verbs with special case government and

others.

1 INTRODUCTION

The research presented in this article describes

methods of modeling semantic and syntactic

valencies of Tibetan verbs in both the formal

grammar and computer ontology and the ways of

automating the modeling process. This work is part

of a study aimed at the development of a formal

model of the Tibetan language, including

morphosyntax, syntax of phrases and hyperphrase

unities, and semantics, that can be used to perform

the morpho-syntactic, syntactic, and semantic

analysis. The development of a full-scale natural

language processing and understanding engine on

the basis of a manually tested corpus of Tibetan texts

continues through several research projects. By the

moment the created corpus (69388 tokens) includes

texts of the Tibetan grammatical tradition and the

theory of writing both in Classical and Modern

Tibetan. The earliest of them are dated back to 7th-

8th centuries. The corpus is provided with metadata

and morphological annotation.

Hereinafter we will use the term ‘semantic

valency’ to denote the ability of a verb meaning to

participate in semantic relations to actants and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0245-5407

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6630-1621

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5429-2051

circumstances of specific semantic classes.

Semantic actants are obligatory participants of the

situation, which can be variable or (in some special

cases) constant; all the other elements are deemed to

be its circumstances. Semantic valencies of verb

meanings are not to be confused with syntactic

valencies of a verb, which refer to the number and

type of dependent syntactic arguments that the verb

can take, and are determined by the morphological

properties of the verb. Therefore, syntactic actants

are specified by the government pattern of a verb

(Mel’čuk, 2004, p. 5-6). The development of

approaches to modeling verbal valencies is very

important for several reasons. For Tibetan verbs,

polysemy is typical. This means that different

meanings of the same verb can have varying

valencies. This ambiguity cannot be resolved on the

levels of morphology and syntax. That's why the

semantic analysis becomes crucially important.

Moreover, unlike many other languages, the

Tibetan language is characterized by a wide use of

verbal compounds derivational models. Without

correct syntactic and semantic models of

compounds, there arises a huge ambiguity for

Tibetan texts segmentation and parsing.

However, the process of modeling verbal

valencies is associated with a number of difficulties.

First of all, there is no universal agreement among

linguists on the list of necessary grammatical

42

Dobrov, A., Kramskova, A. and Smirnova, M.

Modeling Semantic and Syntactic Valencies of Tibetan Verbs in the Formal Grammar and Computer Ontology.

DOI: 10.5220/0010108200420052

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2020) - Volume 2: KEOD, pages 42-52

ISBN: 978-989-758-474-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

categories of the Tibetan verb. Transitivity (an

action being transferred from an agent to a patient)

and volition (explicit or implicit involvement of the

agent) are often mentioned, but described differently

and even intermixed.

In addition, classification of verbal concepts has

to be conducted in accordance with several

classification attributes at once to properly depict

semantic classes of all potential verb actants and

circumstances. The existing classifications of

semantic classes of Tibetan verbs (by S. V. Beyer,

N. Tournadre, B. Zeisler, J. B. Wilson, P. G.

Hackett, N. W. Hill) do not rely on corpus data and

cannot provide a consistent method for categorizing

polysemantic verbs.

All of these reasons led us to establishing a

pragmatic principle for modeling Tibetan verbal

system, according to which only a minimal number

of verbal grammatical characteristics necessary to

perform morpho-syntactic parsing should be

predefined in the formal grammar, while, en masse,

the semantic classification of verbal concepts has to

be based on the syntactic and semantic valencies of

the verbs in the corpus via automated and partly

automated means of text processing.

2 RELATED WORK

Tibetan verbal semantics is a newly established field

of knowledge with many classification models

presented as observations in articles and grammar

books. The majority of the authors agree that

transitivity and/or volition play major roles in

differentiating between Tibetan verbs, but the exact

semantic types are usually not elaborated.

S.V. Beyer names transitivity as the primary

characteristic for verbal distinction that displays

itself at morphological, syntactic and semantic levels

(Beyer, 1992, p. 163). According to his definition,

events denoted by transitive verbs occur through

“agencies” external to their patients, while patients

of intransitive verbs require no such agencies

(Beyer, 1992, p. 252-253). The third major verbal

semantic category he lists is the category of equative

verbs (equational copulas yin and red) which express

the equation of two notions and thus require two

patients. More importantly, S.V. Beyer was the first

to note that “some verbs require additional

participants” (such as locus, accompaniment,

instrument, etc.) and even to touch on semantic

properties of participants for certain verbs (for

example that the patient for the verb thob ‘to get,

attain’ has to be an abstract object) (Beyer, 1992, p.

255).

N. Tournadre sets two basic syntactic and

semantic categories for Tibetan verbs: volition

(“intentional or unintentional nature of the action”)

and valency (the number and types of action

participants) (Tournadre, 1991, p. 95). He also notes

the grammatical difference between volitional and

non-volitional verbs, such as absence of the

imperative stem for non-volitional verbs and their

inability to be supported by intentional auxiliaries.

Later, he further develops this verb classification,

stating that there are four basic classes of verbs:

volitional transitive, volitional intransitive, non-

volitional transitive and non-volitional intransitive

(Tournadre, 2003, p. 142). Additionally, he

describes three types of special “verb constructions”

for some involuntary verbs that require special case

government for the subject and object: egophoric

(e.g., mthong ‘to see’ in (1) has Ergative subject and

Absolutive object), affective (zhed ‘to be afraid of’

in (2) has Absolutive subject and Dative object) and

possessive (skye ‘to be born’ in (3) has Dative

subject and Absolutive object) [3, p. 152-153].

(1) མོས་ང་མཐོང

mo s nga mthong

she ERG I see

‘she sees me’

(2) ི་བ་ི་ལར་ཞེད

byi-ba byi-la r zhed

child cat DAT be_afraid

‘a child is afraid of a cat’

(3) ཕོ་རོག་ལ་་དཀར་མི་ེས

pho-rog la skra-dkar mi skye

raven DAT white_hair NEG be_born

‘the raven does not grow white feathers’

Based on the relation between subject and object

of the verb, J. B. Wilson differentiates three basic

groups of verbs - existential, transitive action verbs

and intransitive action verbs (Wilson, 1992, 531-

532). Additionally, he presents a formal

subcategorization of verbs depending on number and

types of their arguments into three formal classes:

verbs with nominative subjects, with agentive

subjects and verbs in specialized usages. This

system accounts for eight large classes and attempts

to reflect not only syntactic properties of verb

groups, but also judges their semantics (e.g., such

groups as “verbs of dependence,” “verbs of living”).

P. G. Hackett defines Tibetan as an ergative

language where agents of transitive language are

marked with agentive case (Hackett, 2005, p. 2). He

mostly follows Wilson’s classification of Tibetan

verbs, also imputing a notion of “causative and

inchoative” (non-causative) uses of transitive verbs

Modeling Semantic and Syntactic Valencies of Tibetan Verbs in the Formal Grammar and Computer Ontology

43

(Hackett, 2005, p. 6). By inchoative usages he

understands occurrence of transitive verbs in passive

constructions, for example spro ‘to elaborate upon,’

but spro ba ‘elaborated (topic).’

An original semantic classification is provided

by B. Zeisler in “Relative Tense and Aspectual

Values in Tibetan Languages”. She divides all

Tibetan verbs into two groups: control action verbs

(which she also links to the concept of the Tibetan

traditional grammar rang-dbang-can gyi bya-tshig

‘self-powered action words’) and accidental event

verbs (or gzhan-dbang-can gyi bya-tshig ‘other

powered action words’) (Zeisler, 2004, p.250). She

further classifies these categories into subgroups

judging by dynamism, durativity and telicity of the

verbs.

In his classification, N. W. Hill defies the notion

of transitivity for Tibetan verbs altogether, as by his

reasoning, “accusative case has no meaning in

Tibetan”, the category of transitivity itself is not

sufficiently separated from valence, rection and

volition (Hill, 2010, p. xxii). Thus volition, or

control of the action by the agent, becomes one of

the major verbal categories for his system of

classification. Volition of the verb is deducted

judging by its lack or presence of imperative stem.

For the current study we mainly focus on the

category of transitivity, a complex graded

phenomenon that has grammatical manifestation in

Tibetan language in the form of verb valencies.

Volition showed no significant data for the current

research, other than the difference in the number of

verb stems, but it may become an interesting point

for later analysis.

Although the current research was influenced by

some of the mentioned ideas, we couldn’t use any of

the original classifications because of their

limitations in the number of described verbs,

structural inconsistencies. Most importantly, the

main purpose of the present study has been to create

a practice-oriented model that is based on corpus

data and works as part of the Tibetan natural

language processing (NLP).

We consider semantic analysis to be an essential

part of Tibetan NLP due to the ambiguity of both the

segmentation of Tibetan texts into morphemes (since

there are no word delimiters between word forms in

Tibetan writing) and the syntactic parsing. To

resolve the problem of morphosyntactic ambiguity a

computer-based linguistic ontology was developed.

In our project, the term “linguistic ontology” is

understood as a consistent classification of concepts

and relations between them that unite the meanings

of Tibetan linguistic units, including morphemes and

idiomatic morphemic complexes (Dobrov et al.,

2018-1, p. 340).

In the first generations of natural language

understanding systems (NLU systems), ontologies

were used as semantic dictionaries. In the early

1990s, several scholars already used the term

“ontology” in the most general sense, which allowed

linguistic thesauri to be considered as types of

ontologies. The WordNet computer thesaurus has

come to be called an “ontology,” and this trend has

only been growing in the majority of modern works.

Thesauri, including the WordNet, reflect more or

less specified semantic relations between lexical

units (words): synonymy, hyponymy, hypernymy,

antonymy, meronymy, holonymy, logical

entailment, the relation of an adjective to a noun,

etc. (for more information see (Miller, 1995;

Fellbaum, 1998). These relations can be used to

perform lexical disambiguation. Unfortunately, these

relations alone are not enough to solve the problem

of lexical or morphosyntactic ambiguity, especially

in Tibetan, since they do not reflect semantic

valencies (Dobrov, 2014, 114).

The Framenet database initiated by Charles J.

Fillmore covers most of English verbal vocabulary

(“FramNet,” 2020). The verb lexicon VerbNet

(“VerbNet,” 2020) also contains syntactic

descriptions and semantic restrictions for English

verbs. Both of them, however, cannot be considered

linguistic ontologies. Moreover, these resources do

not model the meanings of nouns in relation to

semantic classes created to describe verbal

valencies. The format for presenting information in

both resources is not universal and cannot be used to

model the meanings of lexical units related to other

parts of speech.

PropBank (“PropBank,” 2020) is another verb-

oriented resource that also remains close to the

syntactic level. Despite the fact that it contains

manually made semantic role annotation, it cannot

be used directly to perform semantic analysis.

There are few other resources in the world,

mainly for English and a few of other widely used

languages, that could be classified as linguistic

ontologies, the use of which for semantic

interpretation of syntactic structures is not

impossible, such as SUMO (Dobrov, 2014, p. 149)

and OpenCyc (Matuszek et al., 2006). Both

ontologies are universal and provide profound

classifications of concepts behind lexical meanings,

however, neither one, nor the other is in any way

oriented to verbs, or, moreover, in any way pretend

that it contains all the information about verb

valencies necessary for resolving ambiguity.

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

44

Thus, the existing software tools mainly model

the syntax of verbs or semantics of nouns; and do

not have all the features of linguistic ontologies

necessary for the semantic analysis.

3 THE SOFTWARE TOOLS FOR

PARSING AND FORMAL

GRAMMAR MODELING

This study was performed with use of and within the

framework of the AIIRE project. AIIRE is a free

open-source NLU system, which is developed and

distributed in terms of GNU General Public License

(http://svn.aiire.org/repos/tproc/trunk/t/).

This framework implements the full-scale

procedure of natural language processing, beginning

from graphematics (Aho-Corasick algorithm had to

be used for the Tibetan language due to absence of

word delimiters), continuing with morphological

annotation, going further with syntactic parsing, and

ending with semantic analysis.

Several files were created in order to analyze

Tibetan morphosyntactic structures. The

grammarDefines.py file determines types of atoms

(atomic units), their properties and restrictions.

Other files contain atoms of different types

(v_root_atoms.txt, adj_root_atoms.txt,

adverbs_atoms.txt, etc.). These files are allomorphs’

dictionaries that specify the morpheme, the token

type, and properties for each allomorph, also in

accordance with grammarDefines.py file. At the

present stage, 45 different types of atoms have been

identified. All these types of atoms have their

morphological and morphophonemic features

indicated in the grammarDefines.py file (Dobrov et

al., 2017., 2017, p. 145-146).

For the verbal roots we set the following

potential properties: the mood (indicative,

imperative), the tense (present, past, future), the

availability of transitivity, the availability of tense

category, the availability of mood category, the

availability of ergative, dative, transformative and

associative indirect objects and the type of final

phonemes defining the compatibility of the verbal

root with suffix allomorphs.

The restrictions for the verbal root require that

the category of tense is available only if the

respective parameter “has_tense” is set to “true,”

and the parameter of “mood” is set to “indicative.”

For example, the following entry in the allomorphs

dictionary:’bigs|morpheme=’bigs|type=v_root|dative

=False|mood=ind|has_tense=True|tense=pres|fin_gra

pheme=s|trans=True|transformative=False|associativ

e=False|ergative=True indicates that the ’bigs

allomorph is the basic present tense allomorph of the

morpheme ’bigs ‘pierce,’ this verb root has

indicative mood, it ends in a consonant –s; this verb

is transitive and can also attach an indirect object in

the ergative case.

Syntactic parsing is performed in terms of a

combined constituency and dependency grammar,

which consists of the so-called classes of immediate

constituents (hereinafter CICs). These classes are

developed as python-classes, with the builtin

inheritance mechanism involved, and provide

attributes that specify the following information: the

template of semantic graph which represents the

meaning of this constituent; the lists of possible head

and subordinate constituent classes; the dictionary of

possible linear orders of the subordinate constituent

in relation to the head and the meanings of each

order; the boolean field ellipsis possibility of both

constituents; the boolean field for possibility of non-

idiomatic semantic interpretation (Dobrov et al.,

2019, p. 146).

The grammar is developed in straight accordance

with semantics, in a way that the meanings of

syntactic and morphosyntactic constituents can be

correctly evaluated in accordance with the

Compositionality principle. Each constituent is

provided with a set of semantic interpretations on

the stage of the semantic analysis; if this set proves

to be empty for some versions of constituents, then

these versions are discarded; this is how syntactic

disambiguation is performed.

4 MODELING VERB CONCEPTS

IN THE COMPUTER

ONTOLOGY

4.1 The Software Tools for Ontological

Modeling

The ontology is implemented within the framework

of AIIRE ontology editor software; this software is

free and open-source, it is distributed under the

terms of GNU General Public License, and the

ontology itself is available as a snapshot at

http://svn.aiire.org/repos/tibet/trunk/aiire/lang/ontolo

gy/concepts.xml and it is also available for

unathorized view or even for edit

at http://ontotibet.aiire.org (edit permissions can be

obtained by access request). The basic ontological

editor initially was created for the Russian language.

Modeling Semantic and Syntactic Valencies of Tibetan Verbs in the Formal Grammar and Computer Ontology

45

Its structure and development for Tibetan is

described with examples in (Dobrov et al., 2018a),

(Dobrov et al., 2018b), (Grokhovskii, Smirnova,

2017).

Modeling verb (or verbal compound) meanings

in the ontology is associated with a number of

difficulties. First of all, the classification of concepts

denoted by verbs should be made in accordance with

several classification attributes at the same time,

which arise primarily due to the structure of the

corresponding classes of situations that determine

the semantic valencies of these verbs. These

classification attributes are, in addition to the

semantic properties themselves (such as

dynamic/static process), the semantic classes of all

potential actants and circumstances, each of which

represents an independent classification attribute.

With the simultaneous operation of several

classification attributes, the ontology requires

classes for all possible combinations of these

attributes and their values in the general class

hierarchy.

Special tools were created to speed up and partly

automate verbal concepts modeling. The AIIRE

ontological editor – Ontohelper is used to build the

whole hierarchy of superclasses for any verb

meaning in the ontology. The logic behind this tool

is also based on the division of verbs into dynamic

(terminative and non-terminative) and static ones

(Maslov, 1998). Dynamic verbs express actions,

events and processes associated with different

changes. Static verbs express states, relations or

qualities (Bolshoy entsiklopedicheskiy slovar, 1998,

p. 105). A terminative verb denotes an action which

has a limit in its development. A non-terminative

verb denotes an action which doesn’t admit of any

limit in its development (activity).

When using the Ontohelper editor, it is necessary

to determine whether the verb being modeled

denotes action, state or activity. Terminative, non-

terminative and static verb meanings correspond to

subclasses of concepts ‘to perform an action’, ‘to

perform an activity’ and ‘to be in a state’ in the

ontology, respectively.

The editor of the ontology indicates the basic

class for subjects of the verb to be modeled, as well

as the basic class of direct objects for transitive

verbs and the class of indirect dative objects for

verbs denoting addressed actions. It is also possible

to specify classes of circumstances, i.e., objects with

special case government.

When all the necessary attributes of a verb

meaning are specified, the Ontohelper editor builds

the whole hierarchy of ontological classes from

scratch for this particular combination of attributes,

and if some classes are already present in the

ontology, they are not built again, but tested in terms

of consistency with the current actant / circumstant

relations model.

Thus, despite the fact that the process of

modeling verb valencies is only partly automated,

the developed tool allows to significantly boost the

speed of semantic valencies fine-tuning for verb

classes. For example, modeling the meaning of the

verb ’sbyin ‘to give’ requires 523 classes of verb

concepts to be present or in case of absence to be

created in the computer ontology.

The Ontohelper editor also allows to rebuild the

whole hierarchy in cases when a new actant /

circumstance relation or class has to be established

according to some new observations on the corpus

phenomena.

4.2 Modeling Verbs with Special Case

Government

To model basic valencies it is enough to specify in

the Ontohelper editor classes of possible

subjects/objects/addressees, i.e. the meanings of

nominal groups, attached to standard case markers

(ergative/dative) or used without any marker

(absolutive). The function “Special case

government” allows to model syntactic patterns that

engage specific case markers in specific meaning. In

such cases, for a particular case marker the specific

meaning is described. This case marker meaning, as

well as classes of nominal groups attached to it, are

defined by the main ontology interface. Thus, the

whole modeling process could not be done only with

the use of the editor, therefore verbs with special

case government are treated separately by creating

non-typical semantic classes of verbs in the

computer ontology.

With the help of this function, not only classes of

verb circumstances are modeled, but also some

classes of actants (for example, actants of verbs that

govern the associative case).

In order to establish the relation denoted by a

certain case marker between the meaning of a verb

and the meaning of a noun phrase, it is necessary

that it itself has all necessary relations with these

meanings in the computer ontology. The general

scheme for actions to be done in the computer

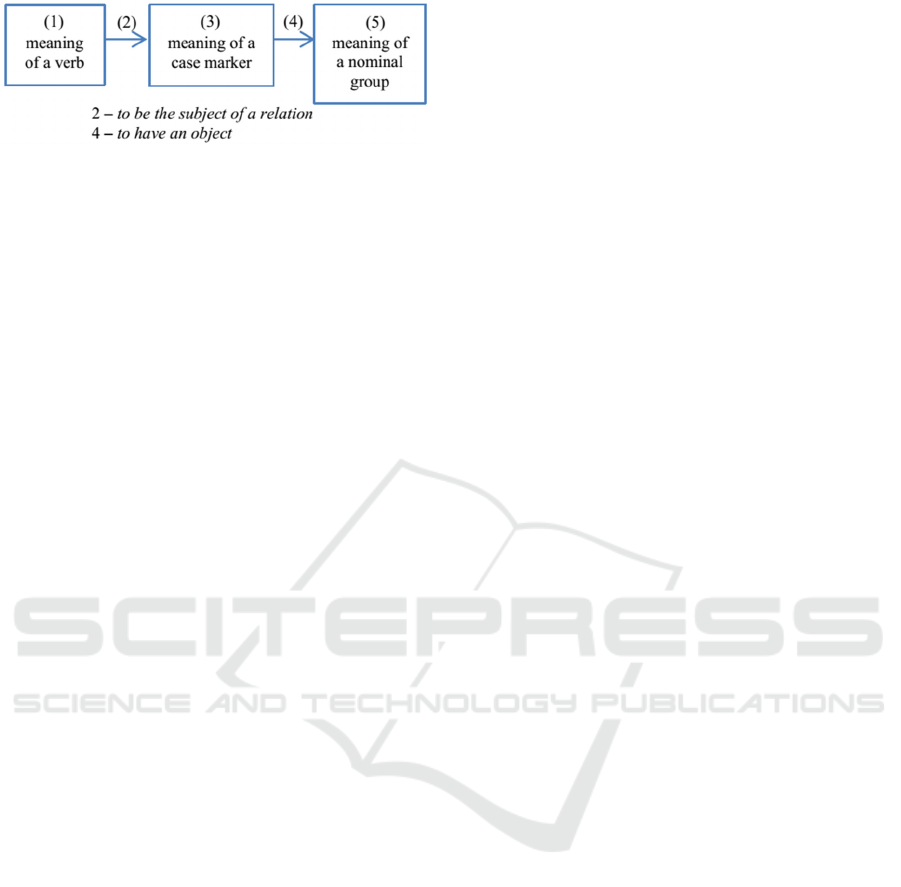

ontology is represented on the Fig. (1).

For example, several verbs found in the texts of

the corpus (e.g., ’byung ‘emerge,’ snang ‘occur,’

’char ‘appear’) can attach a nominal group with the

general meaning “source of origin” using the

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

46

Figure 1: Relations between meanings of verb, case

marker and nominal group.

ablative case marker like in the example (4). For

such verbs a common basic class was created in the

computer ontology – ‘to perform an action of

appearing’ ((1) on the Fig. 1).

(4) ཡི་གེའི་མདོ་ལས་འང

yi-ge ’i mdo las ’byung

phoneme GEN sutra ABL emerge

‘emerge in the “Sutra about phonemes” ’

The meaning of the ablative case marker las is

modelled as a binary relation. For this case we

described the meaning of the case marker as ‘to have

an origin (about an action)’ ((3) on the Fig. 1). The

reverse relation was called ‘to be the origin.’

Between the basic class for verbs ‘to perform an

action of appearing’ and the meaning of the ablative

case marker the relation ‘to be the subject of a

relation’ was established ((2) on the Fig. 1). The

meaning of the ablative case marker was also

connected with the necessary class for nominal

group ‘any object or process’ ((5) on the Fig. 1) with

the relation ‘to have an object’ ((4) on the Fig. 1).

Thus any concept that inherits this class can be a

source or an origin for the mentioned verbs.

After that, when modeling the corresponding

verbs using the Ontohelper editor, it is enough to

indicate the necessary case marker in the column for

special case government, after which the editor

builds the necessary hierarchy of verb classes.

5 VERBAL COMPOUNDS

All Tibetan compounds are created by the

juxtaposition of two existing words. Compounds are

virtually idiomatized contractions of syntactic

groups which have inner syntactic relations frozen

and are often characterized by omission of

grammatical morphemes (Beyer, 1992, p. 102). At

previous stages of our research we distinguished

different types of noun and verbal compounds

depending on the syntactic model of the compound

derivation (full classification is presented in (Dobrov

et al., 2019)).

By the moment the formal grammar contains

CIC for the following basic types of verbal

compounds: verb coordinate compound

(VerbCoordCompound); compound transitive verb

phrase (CompoundTransitiveVP); compound atomic

verbal phrase with circumstance

(CompoundAtomicVPWithCirc) and compound

associative verb phrase (CompoundAssociativeVP).

Verbal compounds like other verbs are processed

using the Ontohelper editor (at present stage of

research meanings of 133 verbal compounds are

modeled in the ontology). In most cases, the direct

hypernym of verbal compounds is the concept

expressed by their verbal component. In other cases,

there is no class-superclass relation between the

meaning of the verbal compound and the verb from

which it is derived. However, their type and valency

are usually the same.

Moreover, it was revealed that

such grammatical features of Tibetan verb

compounds as transitivity, transformativity, dativity,

and associativity are usually inherited from the main

verb, even when the corresponding syntactic valency

seems to be fulfilled within the compound.

Compounds of different types require specific

ontological modeling. The only type of verbal

compounds that does not require establishing any

special semantic relations in the computer ontology

is VerbCoordCompound. These compounds are

contractions of regular coordinate verb phrases with

conjunctions omitted. It is enough that the meaning

of the compound and its components are modeled in

the ontology, and that the general coordination

mechanism is also modeled in the module for

syntactic semantics (the meaning of a coordinate

phrase is calculated as an instance of ‘group’

concept which involves ‘to include’ relations to its

elements).

In compound transitive verb phrase (5), the first

nominal component is a direct object of the second

verbal component. To ensure the correct analysis of

compounds of this type, it is necessary that the

concept of the nominal component of the compound

be a subclass of the basic class specified as a direct

object class for the concept of the verbal component

of the compound. E.g., the literal meaning of the

compound (5) is ‘to fasten help.’ The class ‘any

object or process,’ which includes the concept phan-

pa ‘help,’ was specified as a direct object for the

verb ’dogs ‘to fasten’ (Dobrov et al., 2019, p. 150).

The CIC CompoundAtomicVPWithCirc was

made for a combination of CompoundAtomicVP

(verbal phrase within a compound represented by a

Modeling Semantic and Syntactic Valencies of Tibetan Verbs in the Formal Grammar and Computer Ontology

47

single verb root morpheme – the head class) and the

modifier – CompoundCircumstance, attached on the

left. CompoundCircumstance stood for

circumstances which can be expressed by function

words of different case meanings (e.g., ablative in

(6)).

The relation ‘to have a manner of action or state’

was indicated as a hypernym for all case meanings

of nominal phrases from which compounds with

circumstance are formed. The basic class of the

nominal component should be connected with the

relation ‘to be a relationship object’ with this

relation ‘to have a manner of action or state’.

(5) ཕན་འདོགས

phan-’dogs

help_fasten

‘assist’

(6) ང་འདས

myang-’das

suffer-go_beyond

‘reach nirvana’

The CIC CompoundAssociativeVP was introduced

for contractions of regular associative verb phrases.

It consists of the associative verb (the head class)

and its indirect object. Thus, the first component of

the compound (7) lhag-ma ‘remainder’ should

belong to the class of associative objects specified

for the verb bcas ‘to be together with’ in the

Ontohelper editor (Dobrov et al., 2019, p. 151).

(7) ག་བཅས

lhag-bcas

remainder_be_together

‘have a continuation’

6 IDIOMATICITY

Idiomatic verbal phrases are very common in the

Tibetan language. In Spoken Tibetan, they are even

more frequent than simple verbs (i.e., comprising

one syllable) (Tournadre, 2003, p. 204). However,

since they were not systematically studied with the

involvement of corpus data, the terms used for their

description are vague and sometimes denote

different linguistic phenomena. In particular, in

Tibetologic works one can find such terms as

“phrasal verbs” (Denwood, 1999, p. 109) or “multi-

syllabic verbs” (Wilson, 1992, p. 380),

“compounds” (Beyer, 1992, p. 106), “compound

verbs”(Tournadre, 2003, p. 204).

Despite the fact that our study is based on a

relatively small corpus (the corpus contains 664

simple verb stems, the total frequency of use is

4421), the cases of idiomatic verbal use discovered

in the corpus allow us to preliminarily distinguish

the following types of the idiomatic verbal phrases:

1. Verbal compounds (discussed in section 5 of

this paper) are usually characterized by typical

syntactic structures with the omission of function

morphemes and in most cases express solely

idiomatic meaning.

2. Idiomatic collocations consist of a verb and

different types of complements (usually a noun with

a certain case marker like in (8)).

3. Compound verbs consist of a verb (the so-

called “verbalizer”) and a noun, that is usually a

direct object for the transitive verbs or a subject for

the intransitive verbs. Verbalizers do not convey any

specific meaning, and the meaning of the whole

verbal phrase is determined by the meaning of its

nominal component (like in (9)). The set of

verbalizers is supposedly limited. The most frequent

are: gtong ‘to send,’ rgyag ‘to send off,’ byed ‘to

do.’

(8) ཁས་ལེན

kha s len

mouth ERG take

‘assert’

(9) མེ་མདའ་ག

me-mda’ rgyag

gun send_off

‘shoot’

Verbal phrases of these types, including verbal

compounds, retain a certain syntactic flexibility. A

verb can be separated from the rest part of a phrase

by the negative particle, adverb, adjective or another

complement. For example, in the example (11)

compound verb (10) is split by the adverb zhib-mor

‘thoroughly.’

(10) བསམ་ོ་གཏོང

bsam-blo gtong

thinking send

‘to think over’

(11) དད་པ་འདི་བསམ་ོ་ཞིབ་མོར་བཏང

dpyad pa ’di bsam-blo zhib-mor

btang

investigate-NOM DEM thinking

thoroughly send

‘to think thoroughly over this

investigation’

The semantic valency in these phrases differs from

that of the initial verbs, but syntactic valency can be

inherited from the basic verb, even when it seems to

be fulfilled within the verbal phrase like in (10).

Though in some cases, compound verbs and

verbal compounds cannot attach a direct object, but

remain ergative, which can be explained by the fact

that the noun preceding the verb can be analyzed as

an internal object. Thus the verbalizer acts as an

autonomous transitive verb (Tournadre, 2003, p.

207).

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

48

Methods of verbal compounds modeling are

described in section 5. Verbs from phrases of the

second and third types are modelled via the

Ontohelper editor as cases of polysemy – as separate

concepts of the same expression. To avoid

ambiguity the meaning of the very noun, which was

used in the idiomatic verbal phrase, is specified as a

possible subject or object. For example, the literal

meaning of the transitive verb len from (8) is “to

take.” Its direct hypernym will be ‘to perform an

unaddressed action of any creature directed toward

an object.’ Such hypernym excludes the version in

which kha ‘mouth’ can take something (i.e., to

assert). Thus, to ensure the possibility of the

idiomatic use of this verb the second meaning ‘to

assert’ is modelled in the ontology. For this meaning

the Tibetan word kha ‘mouth’ is indicated as the

subject of the action. Thus, a hypernym of the

second concept of the expression len will be ‘to

perform an undirected unaddressed action of kha.’

Still due to syntactic flexibility and possible

change in semantic valency, the cases of verbal

idiomatic use and ways of modeling of their

meanings should be specifically investigated on the

basis of a larger corpus.

7 AUXILIARY VERBS AND

COPULAS

One of the Tibetan verbal properties according to the

created formal grammar is transitivity that is the

property of verbs that relates to whether a verb can

take direct objects (‘trans’). For main verbs the value

of this property is only ‘true’ or ‘false’. For

auxiliaries and equative verbs the values ‘aux’ and

‘copula’ were added.

Equative and Auxiliary verbs are represented in

the formal grammar by separate classes –

CopulaGroup and AuxVPNoTenseNoMood

respectively. The class for copula group consists of

an equative verb (the head class) and a noun phrase

(the argument). In the CIC AuxVPNoTenseNoMood

the auxiliary or modal verb is considered to be the

head class, while the main verb with the intersyllabic

delimiter form the argument class attached on the

left.

Auxiliary verbs in Tibetan can indicate aspect

(how an action or state extends over time), mood,

tense, evidentiality (source of information) and vary

depending on the verb's volition.

Tibetan equatives and existential verbs can act

both as main verbs (12) and as auxiliaries (13).

(12) ་ཡོད

rta yod

horse exist

‘[there] is a horse’

(13) ་ར་ཡོད

sgra sbyar yod

grammatical_marker add-

AUX

‘[somebody] has added

grammatical marked’

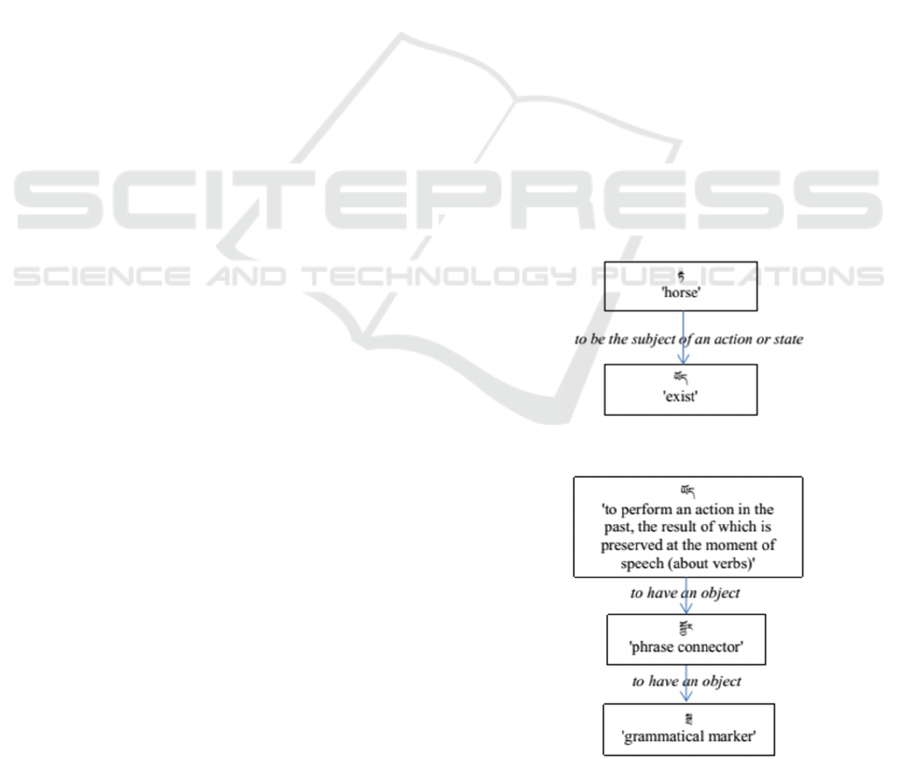

To ensure the correct semantic parsing of (12)

the meaning of the existential verb yod ‘to exist’ was

modelled in the computer ontology using the

Ontohelper editor. After the type of a verb and a

class of possible subjects, that is ‘any object or

process,’ was specified, the editor built the whole

hierarchy of verb’s superclasses with the direct

hypernym ‘to be in an undirected, unaddressed state

of an object or process.’

Like other verbs, auxiliary verbs are processed

using the Ontohelper editor. Auxiliary verbs

(including modal verbs) govern verb phrases instead

of nominal ones, therefore, semantically are treated

as transitive verbal phrases. Thus, the basic class for

all verbs in the ontology ‘to perform an action or

state’ is indicated as a direct object of auxiliary

verbs in the Ontohelper editor. As a result we get the

direct hypernym of the auxiliary verb – ‘to perform

an unaddressed action of someone directed toward

his own action or state.’ The semantic graphs for the

phrases (12) and (13) are presented on the Fig. (2)

and (3) respectively.

Figure 2: Semantic graph for the phrase (5).

Figure 3: Syntactic graph for the phrase (6).

Modeling Semantic and Syntactic Valencies of Tibetan Verbs in the Formal Grammar and Computer Ontology

49

As it is shown on the Fig. 3 the action of the

auxiliary verb yod is directed toward the notional

verb sbyor ‘to add,’ while the direct object of the

verb sbyor is the noun sgra ‘grammatical marker.’

8 SEMANTIC CLASSES OF

TIBETAN VERBS

The data on Tibetan verbs extracted from the created

ontology allowed to identify typical semantic classes

of modelled verbs according to several classification

attributes: type of the verb (dynamic or static),

indicated classes for subjects and direct and indirect

objects. For example, Table 1 represents a particular

combination of attributes that represents the

semantic class ‘to perform a liberative action of any

creature directed toward any object or process.’

Table 1: The semantic class ‘to perform a liberative action

of any creature directed toward any object or process’.

Type of verb dynamic

Special case government (SCG)

type

liberation

SCG case Ablative

SCG semantic class object or process

Subject any creature

Direct object object or process

Amount of verbs 2

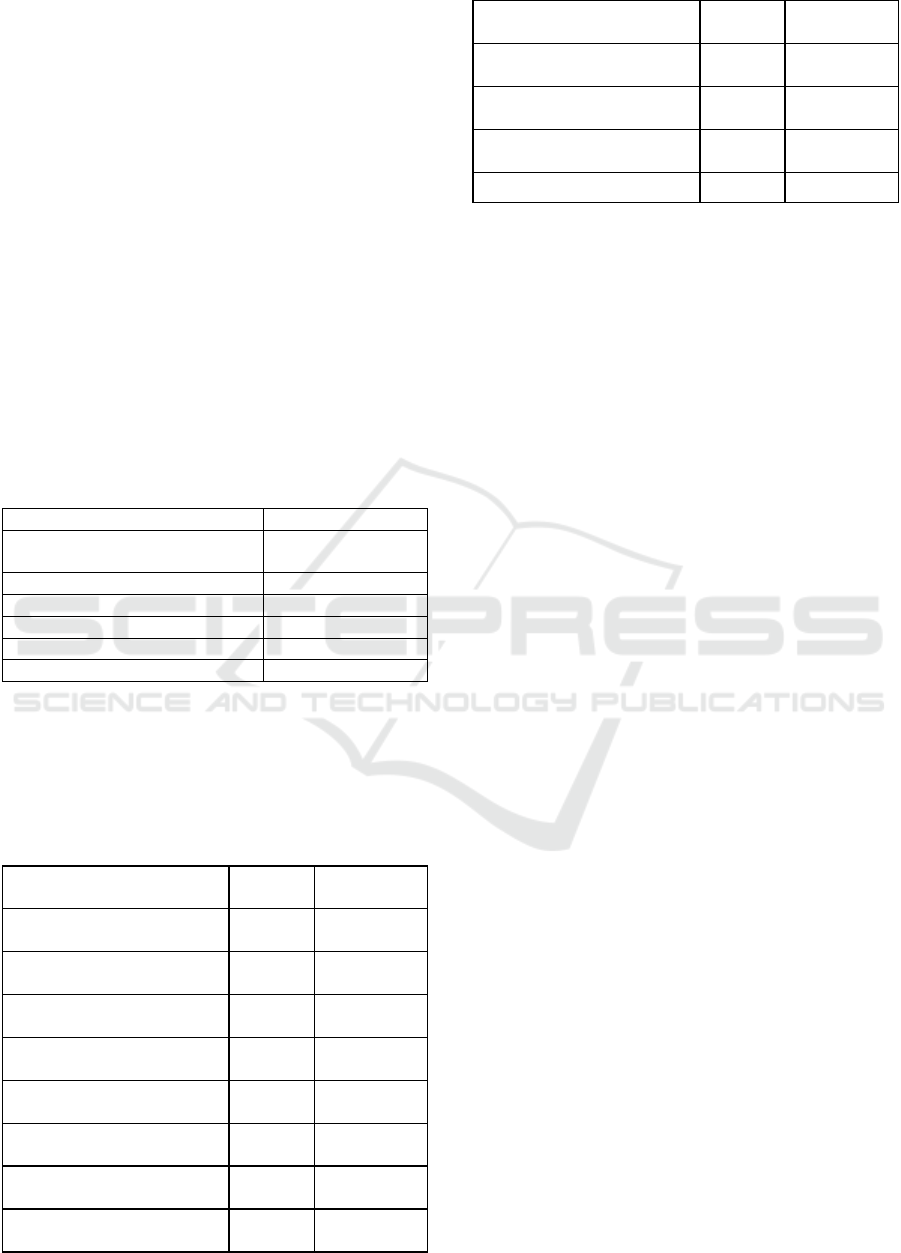

The frequencies of modelled simple verbs

grouped by their type, addressedness, transitivity

and SCG along with the correlating semantic classes

are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: The statistics on verbal concepts in the computer

ontology.

Verbs Semantic

classes

Dynamic addressed transitive

no SCG 6 4

Dynamic addressed transitive

SCG 2 1

Dynamic addressed

intransitive no SCG 13 5

Dynamic unaddressed

transitive no SCG 174 53

Dynamic unaddressed

transitive SCG 18 13

Dynamic unaddressed

intransitive no SCG 64 14

Dynamic unaddressed

intransitive SCG 26 12

Static addressed transitive no

SCG 1 1

Static addressed intransitive

no SCG 9 2

Static unaddressed transitive

no SCG 2 2

Static unaddressed

intransitive no SCG 65 14

Static unaddressed

intransitive SCG 6 3

Total amount 386 124

The dynamic unaddressed transitive no SCG

verbs expectedly make up for the biggest statistical

group, with semantic classes denoting actions of

different actors, the largest of which are two classes

of general actions of any creature directed at an

object or process (44 verbs, e.g., gsang ‘to hide’)

and at an object (43 verbs, e.g., ’joms ‘to destroy’).

They are followed closely by a large semantic

class of “motion verbs” that denote dynamic

intransitive unaddressed actions of any creature (27

verbs, e.g., gshegs ‘to come’) and “qualitative verbs”

that denote intransitive unaddressed states of objects

or processes (22 verbs, e.g., mang ‘to be abundant’).

Despite the fact that the amount of modelled

verbs’ meanings is not large, the resulting data has

already revealed some interesting linguistic

phenomena. One of them is semantic division

between stative verbs that produce adjectives and

stative verbs that do not. Among all the semantic

classes created for static verbs, 12 classes seem to

form a larger semantic group of “qualitative verbs”

(verbs that answer the question “to have what

quality”).

These 12 verb classes (62 verbs) comprise the

majority of static verbs as such that differ only in

subject. Twenty two verbs denote qualitative states

performed by ‘any object or process’ (e.g., bzang ‘to

be good’), the possible subjects of 15 verbs are

united by the class ‘any object’ (e.g., drag ‘to be

firm’) and 7 verbs denote state that can be performed

only by ‘any creature’ (e.g., phyug ‘to be wealthy’).

All of the verbs that belong to these classes can

obviously produce proper adjectives with the help of

suffix -po/bo (e.g., phyug-po ‘rich’).

The remaining 9 semantic classes of static verbs

(21 verbs) do not produce adjectives. A number of

them constitute existential and equational copulas.

Three classes consist of verbs denoting special

states, like cooperative state (e.g., bcas ‘to be

together with’) or comparative state (e.g., phud ‘to

be the best of’). The last two classes contain 9 so-

called “mental verbs” that denote either emotions or

states of the subject’s mind (e.g., skrag ‘to fear’).

Division into semantic classes not only

represents basic statistics on types, transitivity,

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

50

addressness and special case government of verbs

modelled in the ontology, but also allows to indicate

larger semantic entities that would include several

semantic classes (e.g., “qualitative verbs,” “mental

verbs,” etc.).

Additionally, typical semantic valencies of

modeled Tibetan verbs allow us to draw some

conclusions about the Tibetan linguistic picture of

the world. For example, the most frequently used

class of subjects is the basic class ‘any creature’ (73

semantic classes), while for the Russian language it

is the class ‘any person’. At the moment, this basic

class includes several hyponyms in the ontology,

some of which include only humans (e.g., mi

‘human’), and others unite people and animals (e.g.,

sems-can ‘sentient being having a dualistic mind,’

’gro-ba ‘migrator,’ skyes-ldan ‘having a birth’) or

even people, gods and Buddhas (e.g., ‘any creature

that is not an animal’).

9 CONCLUSIONS

The process of the formal grammatical and

ontological modeling of Tibetan verbs and its

current results presented in this article continue to

represent one of the first formal automated

descriptive systems for Tibetan language material.

Pragmatic approach to modeling Tibetan verbal

system that is centred around solving tasks of the

Tibetan language module as part of text processing

system, allows to follow less of the disputable

grammatical theories and more of the actual corpus

data.

Further work will include the development of

semantic annotation, and if necessary the correction

of formal grammar according to new linguistic

phenomena found in the texts of the corpus. We

hope to create more detailed semantic verb

classification based on verbal syntactic and semantic

valencies, including idiomatic verbal phrases. The

complete description of the semantic classes of

Tibetan verbs also requires a deeper understanding

of the division between semantic classes of Tibetan

nouns that we hope to achieve in further studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Russian Foundation

for Basic Research, Grant No. 19-012-00616

Semantic interpreter of texts in the Tibetan

language.

REFERENCES

Beyer, S., 1992. The Classical Tibetan Language. State

University of New York.

Bolshoy entsiklopedicheskiy slovar, Yazyikoznanie, [Great

Encyclopedical Dictionary, Linguistics], 1998.

Nauchnoe izdatelstvo “Bolshaya Rossiyskaya

entsiklopediya” [Scientific Publishing House “Great

Russian Encyclopedia”].

Denwood, P., 1999. Tibetan. John Benjamins.

Dobrov, A.V., 2014. Avtomaticheskaja rubrikacija

novostnyh soobshhenij sredstvami sintaksicheskoj

semantiki [Automatic classification of news by means

of syntactic semantics], [Doctoral Thesis, Saint-

Petersburg State University]. Dissertation Committee

of Saint-Petersburg State University. URL:

https://disser.spbu.ru/files/disser2/disser/dobrov_disser

t.pdf

Dobrov A.V., 2014. Semantic and Ontological Relations

in AIIRE Natural Language Processor. In

Computational Models for Business and Engineering

Domains, 147-157

Dobrov A., Dobrova A., Grokhovskiy P., Smirnova M.,

Soms N., 2018a. Computer Ontology of Tibetan for

Morphosyntactic Disambiguation. In Digital

Transformation and Global Society. DTGS 2018.

Communications in Computer and Information

Science 859, 336–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-

030-02846-6_27

Dobrov, A., Dobrova, A., Smirnova, M., Soms, N., 2019.

Formal grammatical and ontological modeling of

corpus data on Tibetan compounds. In Proceedings of

the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management, Volume 2, 144–153.

https://doi.org/10.5220/0008162401440153

Dobrov A., Dobrova A., Grokhovskiy P., Smirnova M.,

Soms N., 2018b. Idioms Modeling in a Computer

Ontology as a Morphosyntactic Disambiguation

Strategy. In Text, Speech, and Dialogue. TSD 2018.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11107, 76-83.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00794-2_8

Dobrov A., Dobrova A., Grokhovskiy P., Soms N.,

Zakharov V., 2016. Morphosyntactic analyzer for the

Tibetan language: aspects of structural ambiguity. In

International Conference on Text, Speech, and

Dialogue, 215-222. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-

45510-5_25

Dobrov A., Dobrova A., Grokhovskiy P., Soms N., 2017.

Morphosyntactic Parser and Textual Corpora:

Processing Uncommon Phenomena of Tibetan

Language. In Internet and Modern Society.

Proceedings of the International Conference IMS-

2017, 143-153.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3143699.3143719.

Fellbaum, Ch., 1998. WordNet: An Electronic Lexical

Database. Mass: MIT Press.

FrameNet. URL:

https://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu/fndrupal/

(Accessed: 21.06.2020).

Modeling Semantic and Syntactic Valencies of Tibetan Verbs in the Formal Grammar and Computer Ontology

51

Grokhovskii P., Smirnova M., 2017. Principles of Tibetan

Compounds processing in Lexical Database. In

Proceedings of the International Conference IMS,

135-142. https://doi.org/10.1145/3143699.3143718

Hackett, P.G., 2005. A Tibetan Verb Lexicon: Verbs,

Classes, and Syntactic Frames. Snow Lion

Publications.

Hill N. W., 2010. A Lexicon of Tibetan Verb Stems as

Reported by the Grammatical Tradition. Bayerische

Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Maslov, Yurij S., 1998. Glagol (Verb). In Bolshoy

entsiklopedicheskiy slovar, Yazyikoznanie [Great

Encyclopaedical Dictionary, Linguistics], 104-105.

Nauchnoe izdatelstvo “Bolshaya Rossiyskaya

entsiklopediya” [Scientific Publishing House “Great

Russian Encyclopedia”].

Matuszek C., Cabral, J., Witbrock, M. J., & DeOliveira, J.,

2006. An Introduction to the Syntax and Content of

Cyc. In AAAI Spring Symposium: Formalizing and

Compiling Background Knowledge and Its

Applications to Knowledge Representation and

Question Answering, 44-49.

Mel'cuk, I., 2004. Actants in semantics and syntax I:

actants in semantics. In Linguistics, 42, 1-66.

https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.2004.004

Miller, G.A., 1995. WordNet: A Lexical Database for

English. In Communications of the ACM, Volume 38,

No. 11, 39-41. https://doi.org/10.1145/219717.219748

Propbank. The Proposition Bank (PropBank) URL:

https://propbank.github.io/ (Accessed: 21.06.2020).

Tournadre, N. Sangda Dorje, 2003. Manual of Standard

Tibetan. Snow Lion Publications.

Tournadre, N., 1991. The rhetorical use of the Tibetan

ergative. In Linguistics of Tibeto-Burman Area 14(1),

93-107.

VerbNet. A Computational Lexical Resource for Verbs.

http://verbs.colorado.edu/~mpalmer/projects/ace.html

(Accessed: 21.06.2020).

Wilson, J.B., 1992. Translating Buddhism from Tibetan.

Snow Lion Publications.

Zeisler, B., 2004. Relative Tense and Aspectual Values in

Tibetan Languages: A Comparative Study. Trends in

Linguistics. Studies and Monographs [TiLSM]. De

Gruyter Mouton.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110908183

KEOD 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

52