A Measurement Model to Identify Knowledge-intensive Business

Processes in SMEs

Christian Ploder

a

MCI Management Center Innsbruck, Universit

¨

atsstrasse 15, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria

Keywords:

Knowledge-intensive Business Process, Measurement Model, SME.

Abstract:

This paper is based on earlier work about the selection of knowledge-intensive business processes in SMEs

done by the author with the result of defining 15 different factors in four categories: process, people, task and

interdependencies. The developed factor model for describing the knowledge-intensive business process is

driven further within the last year to help small and medium sized enterprises to focus on their important busi-

ness processes if starting with process management initiatives. The developed factor model was enriched with

a measurement model that combined scientific and practical input. This paper presents the measurement model

that is at least able to divide between knowledge-intensive business processes and not knowledge-intensive

business processes in a company. It is essential to invest in the right business processes for improvement if

it comes to process management according adopting current challenges for SMEs, which are fulfilling any

quality management norm like ISO 9000 series.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge serves as the basis for a competitive ad-

vantage that can be maintained over the long term

(Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1998). It can thus be de-

duced that one way of securing corporate activity in

the long term could be for companies to learn faster

than their competitors (Senge, 1996). The efficiency

with which knowledge is processed in companies is

a decisive factor in ensuring a company’s continued

existence. The consistent cultivation of specific expe-

rience is developing into a priority management task

for companies (Probst et al., 2006).

The discussion on knowledge management has

mostly focused on large companies. Topics such as

corporate culture, stakeholder networking, organiza-

tional structures, and technologically based infras-

tructures were examined based on the implementa-

tion of knowledge management in large companies.

However, no focus was placed on the unique needs

of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (De-

lahaye, 2003). Knowledge management has also be-

come a crucial task in SMEs (Durst and Edvardsson,

2012) (Saloj

¨

arvi et al., 2005). Desouza and Awazu

(Desouza and Awazu, 2006) believe that SMEs can

achieve their competitive advantage by actively man-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7064-8465

aging their knowledge. McAdam and Reid (McAdam

and Reid, 2001) also point out the importance of an

independent view of SMEs. A comparative empir-

ical study by the two authors shows that both large

companies and SMEs can benefit from implement-

ing knowledge management. Dunkelberg and Wade

(Dunkelberg and Wade, 2007) think that a conscious

and systematic implementation of knowledge man-

agement has a positive influence on the development

of a company.

According to Edwards and Kidd (Edwards and

Kidd, 2003), there are four possible approaches to

implementing knowledge management in companies:

(1) the ”Knowledge World” way, (2) the ”IT-driven”

way, (3) the ”Functional” way and (4) the ”Business

Process” way and some of the reasons for the ”Busi-

ness Process” way are already given. For this paper,

the focus on the ”Business Process” way selected be-

cause of the current developments regarding changes

in the area of auditing based on quality management

norms. Current developments in the area of ambidex-

terity and agile auditing are one of the main topics

of the author’s research unit, where the whole team is

currently doing much empirical work in. From a prac-

tical point of the changes in the last versions of quality

management norms like ISO 9001, ISO 14385, and so

on, develop into a more agile idea of auditing develop-

ing companies to the permanent audit readiness. Fur-

Ploder, C.

A Measurement Model to Identify Knowledge-intensive Business Processes in SMEs.

DOI: 10.5220/0010014601330139

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2020) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 133-139

ISBN: 978-989-758-474-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

133

thermore, this work should help companies to filter

their business processes by the most important ones

to put effort into these processes first to fulfill the ex-

ternal requirements and improve internal governance.

Based on this problem description, the follow-

ing research question can be determined: How can

a measurement model for knowledge-intensive busi-

ness processes look like for SMEs?

To answer this research question the theoretical

foundation will be built up in section 2 followed by a

short explanation of the related work in section 3. The

conducted empirical study will be explained in sec-

tion 4 followed by the results and a discussion given

in section 5. A conclusion is given in section 6 fol-

lowed by the limitation and future research in section

7.

2 THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

The two main concepts needed for this study are,

on the one hand, the model concept and the term of

the knowledge-intensive business processes. Both of

these concepts are described in the tow following sub-

sections.

2.1 The Model Concept

The formation of a model to describe a specific sec-

tion of reality is called modeling. Analysis and struc-

turing of the given data material lead to the forma-

tion of concepts and, thus, to a structural concept for

the model. The model subdivides the examined sec-

tion of reality by assigning a system of concepts to

the unstructured initial data and thus determines their

meaning and their relationships with each other. The

structural concept always considers only one particu-

lar view of the section of reality to be modeled (Hein-

rich et al., 2014, p. 437). The following statements

all refer to the model which is created in the course of

this work, and the forms of expression are explained

accordingly:

• The object type is a process model. The model to

be created will describe the process of diagnosis.

The individual process steps can be derived from

the model and operationalized. It thus describes

the path of diagnosis in addition to the description

of the real-world object.

• The degree of formalization of the model de-

scribes its description possibilities. The model to

be formed in this thesis can be described as for-

mal because it can be fully represented utilizing

mathematical symbols. However, this does not

exclude another form of representation but repre-

sents a minimum requirement.

• A mathematical representation of the model is

decisive for a corresponding classification in the

criterion of the form of representation. The

model to be created serves as a possibility to dif-

ferentiate between knowledge-intensive and non-

knowledge-intensive business processes based on

evaluated criteria that can be put into a mathemati-

cal context. A mathematical representation, there-

fore, becomes inevitable. In order to present the

process of diagnosing in a more comprehensible

way, graphic forms of representation will also be

necessary. Thus, there is no double mention of

the form of representation in the special case of

the diagnosis model.

• The model forms the basis for differentiating

whether a particular process is a knowledge-

intensive or a non-knowledge-intensive business

process - which is why a decision is ultimately

made.

• The causality structure can be assumed to be lin-

ear since a linear relationship can be established

between the elements with their characteristics

and their effects on the model. Furthermore, no

feedback on the elements is possible.

• The model to be formed in work is not a meta-

model since it does not contain construction rules

and interpretation hints of models. These two re-

quirements would indicate a meta-model.

In summary, it can be said that the division, according

to Heinrich et al. (Heinrich et al., 2014) is a descrip-

tive model that is formed inductively. The require-

ment of structural similarity cannot be fulfilled due to

the exploratory character of the model and the asso-

ciated uncertainty about the number of elements and

their relations - however, structural similarity can be

assured based on empirical findings. The validity of

the model is ensured due to a methodically clean pro-

cedure in model building.

2.2 The Knowledge Intensive Business

Process Concept

Separate consideration of knowledge-intensive busi-

ness processes can be seen as positive from several

perspectives: A closer look at business processes (Du-

mas et al., 2013) and their supporting knowledge pro-

cesses gives knowledge management a much stronger

link to the value chain (Skyrme, 1998). Some au-

thor assume that a combined view has a positive ef-

fect on the design and implementation of knowledge

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

134

management systems through the gained process ref-

erence (Mentzas et al., 2001). A combination of busi-

ness process modeling with knowledge management

activities can support change processes and innova-

tion. Knowledge management is introduced for core

processes (Davenport and Prusak, 2000) and supports

them efficiently (Mertins et al., 2001). These and

other aspects of (Oesterle and Winter, 2000) can be

seen as important advantages of a combined approach

(Remus, 2002).

Since there is currently no clear definition for

knowledge-intensive business processes, the follow-

ing section presents some definitions that need to be

considered in a differentiated manner and from which

a definition that is useful for the work is worked out,

which will determine the further procedure. Finally,

as a result of the present work, a model will be de-

veloped, which tries to divide between knowledge-

intensive and non-knowledge-intensive business pro-

cesses possible using factors.

In a paper by Goesmann and Hoffmann (2000), a

definition of the term knowledge-intensive business

processes is presented as follows: ”Processes [...]

with a high proportion of information processing ac-

tivities, in which unpredictable information require-

ments arise and new information is frequently gener-

ated [...]. Further characteristics are [...] high adjust-

ment requirements and high decision-making leeway

of the employees” (Goesmann and Hoffmann, 2000).

This definition shows a technocratic understanding of

knowledge-intensive business processes.

With Remus (2002), on the other hand, a partial

aspect of knowledge-intensive business processes can

be seen as follows: ”...knowledge-intensive business

processes make greater use of knowledge in the pro-

duction of goods and services than conventional pro-

cesses (Remus, 2002, p. 38). This definition is based

on the concept of knowledge, which was coined from

knowledge management, without going into its fuzzi-

ness in detail. Richter-von Hagen et. al. (Richter-von

Hagen et al., 2005) offers a definition that also refers

to this knowledge: ”A process is knowledge-intensive

if its value can only be created through the fulfillment

of the knowledge requirements of the process partici-

pants. From this, it can be seen that the corresponding

process participants very often provide the required

process knowledge and that the human factor must not

be forgotten in a closer examination.

A further definition can be found in Maier (Maier

and Thalmann, 2007, p. 212f), following Allweyer

(Allweyer, 1998): ”This Term denotes a business pro-

cess that relies substantially more on knowledge in

order to perform the development of production of

goods and services than a ”traditional” business pro-

cess”. Furthermore, Maier (Maier and Thalmann,

2007) writes about knowledge-intensive business pro-

cesses: ”...every type of business process is a poten-

tial candidate for a knowledge-intensive business pro-

cess”. It is precisely this statement on the occurrence

of knowledge-intensive business processes that calls

for the elaboration of the present paper, the aim of

which is to achieve a classification into knowledge-

intensive and non-knowledge-intensive business pro-

cesses.

As a summary of the different definitions pre-

sented here, it can be assumed that the description

of a knowledge-intensive business process can by no

means be dealt with in one sentence. The broad view

that the knowledge-intensive business process is char-

acterized by a higher knowledge share of the process

participants is also supported in this thesis. Other ad-

ditional factors which can be descriptive of the knowl-

edge intensity of business processes are found, among

others, in Eppler et al. (Eppler et al., 2008), Goess-

mann Hoffmann (Goesmann and Hoffmann, 2000),

Gronau et al. (Gronau et al., 2005) or Remus (Remus,

2002).

3 RELATED WORK

As mentioned in the introduction, the factor model

itself was developed and presented in earlier work

(Ploder and Kohlegger, 2018) by the author and will

only be described rough in this paper for better under-

standing of the measurement model. To build the fac-

tor model a study in Austrian SMEs was conducted

based on the structured case approach (Carroll and

Swatman, 2000) with the aim to find out which are the

relevant factors to filter the knowledge-intensive busi-

ness processes. Within three iteration steps the factor

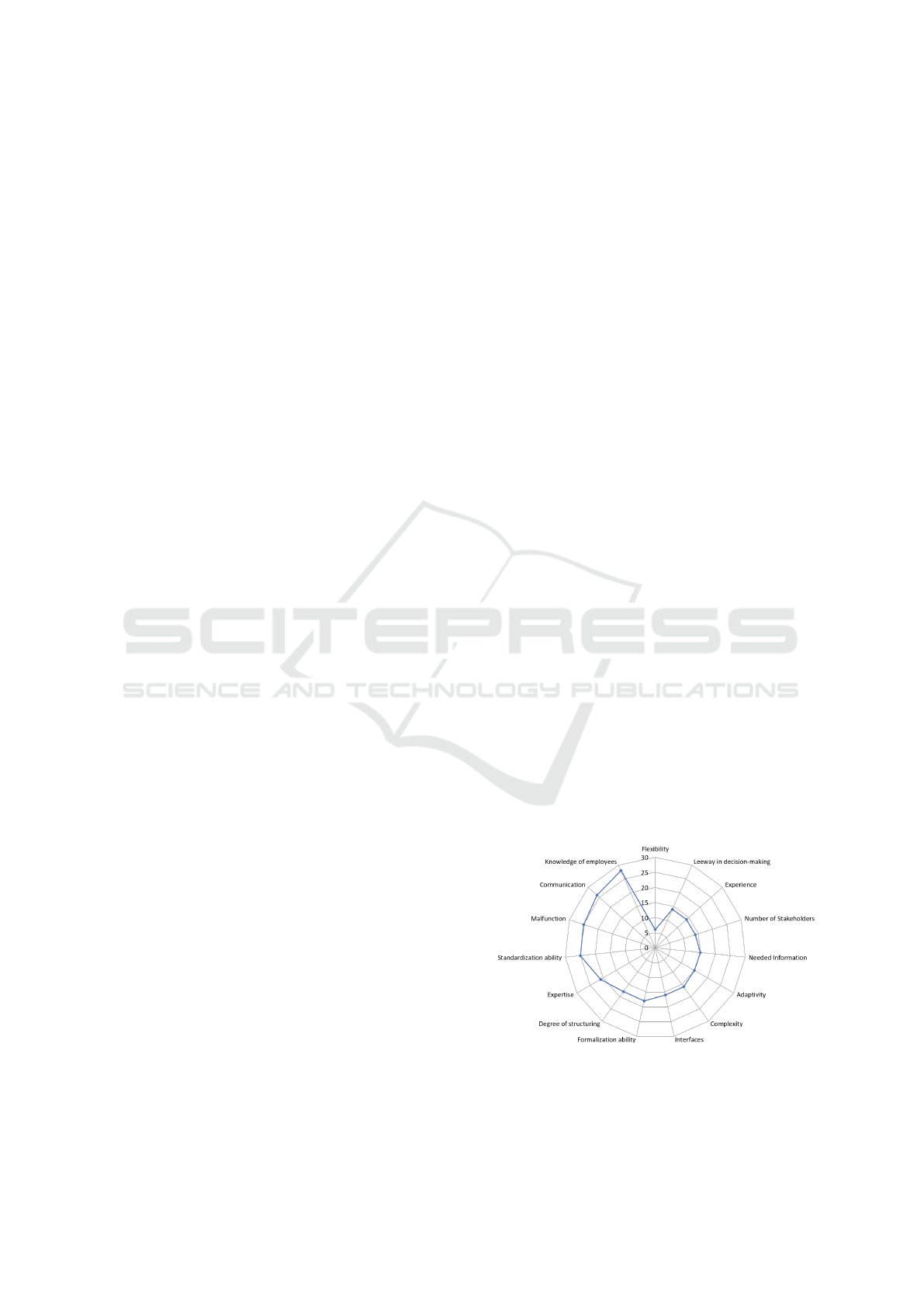

model has been developed and is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Factor model by frequency of responses.

All the factors have first been elaborated from lit-

erature and later on expanded by expert interviews to

A Measurement Model to Identify Knowledge-intensive Business Processes in SMEs

135

make a identification of the knowledge-intensive busi-

ness processes possible. But there was no weighting

and no calculation scheme available for the measure-

ment of different processes in SMEs. How this cal-

culation scheme was developed will be shown in the

section 4.

4 EMPIRICAL STUDY

The empirical study was based on Austrian SMEs as

defined by the EU based on the three factors: (1)

headcount less than 250 employees, (2) transaction

volume less than 50 Mio. Euro and (3) a balance sheet

total of less than 43 Mio. Euro. However, there is a

second limiting factor that is essential to this study’s

validity. This factor is the certification of the respec-

tive companies according to the ISO 9001 standard

because these companies are familiar with the process

management idea and have to deal with current devel-

opments like permanent audit readiness. In contrast

to the first study, the data evaluation for this paper is

quantitative because it is all about setting the meas-

ruements for the categroies and the factors itself. For

this purpose, the results were transferred to a spread-

sheet program and analyzed through statistical proce-

dures (frequency analysis and concluding statistical

values to check the data material).

Based on the first empirical study explained in

Ploder and Kohlegger (Ploder and Kohlegger, 2018)

the same experts have been interviewed for a second

time in 2019 with a structured interview guideline to

get answers on the following questions: (1) how can

the measurement of the factors from the first three cy-

cles be described, (2) how can the directions of ac-

tion of the factors be described, (3) how can the dis-

tribution of the weightings of the four categories be

described and (4) how could a mathematical model

for evaluation look like. The generation of the ques-

tions was following the SPSS method to focus on the

most important questions during the strict guided in-

terviews (Helfferich, 2011).

To get answers on the four given questions, the in-

terview guide was designed to be a quantitative study.

In the first two questions, all 15 factors were given to

the experts, which were then ranked by the experts on

the one hand concerning their relevance (question 1)

for distinguishing between knowledge-intensive busi-

ness processes and non-knowledge-intensive business

processes. On the other hand, the direction of effect

(question 2) of the factors on the knowledge intensity

of a process was determined. The relevance check

was carried out using an ordinal scale from ”very rel-

evant” to ”not relevant” for each factor. It is also im-

portant to note that it is the relevance of the factor and

not its impact that is at issue.

The experts rated the direction of impact as pos-

itive or negative with maximum expression of the

factor. An example of a negative direction of ef-

fect would be: ”If the formalizability of a process

is rated very high, this would rather indicate a non-

knowledge-intensive business process”.

Question three in the expert interview guidelines

had to deal with the question of the weighting of

the categories (question 3) and a calculation (ques-

tion 4) based on this for the classification. For this

purpose, four different scenarios with two differenti-

ated approaches were chosen. These scenarios were

specified in order to make it easier for the experts to

make an assessment and to be able to determine a ten-

dency from the expert interviews, which of them are

suitable for the diagnosis model. The two differenti-

ated approaches differ in that only a minimum value at

achievable points of the 15 factors is decisive for the

classification, and it can, therefore, be the case that

a category is assessed as very low and yet an overall

value indicates a rather knowledge-intensive business

process. This approach has been given two different

values for overall rating of all factors: Scenario one

with 75 percent or scenario two with 50 percent.

Scenarios three and four, on the other hand, are

based on the approach that a minimum value must be

achieved both overall and in each category. To allow

the experts to make an individual proposal, scenario

5 provides the opportunity to present a particular sce-

nario.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

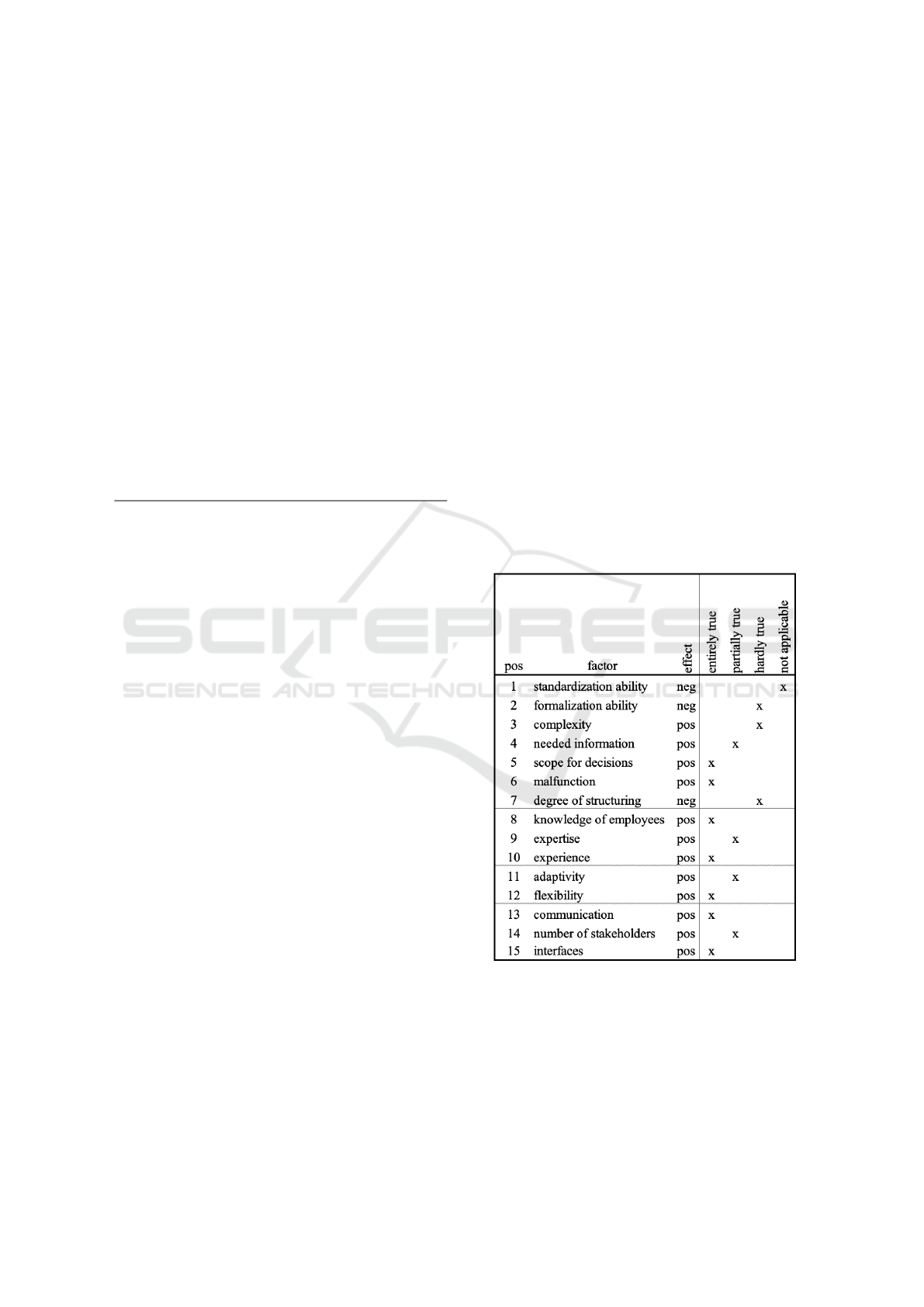

The evaluation of data gained from question 1 show

that there is no factor which the experts consider to

be irrelevant and all of them are taken for the mea-

surement model as shown in table 1. The factors are

listed in the columns and assigned to the correspond-

ing categories. Based on the ordinal distributed data,

an aggregated measure of the relevance of the indi-

vidual factors is formed not with the mean value, but

with the median. For the coding from ”very relevant”

to ”not relevant,” the numerical values were used in

steps of 1 from 3 to 0. This shows that the majority of

the factors were rated ”relevant” or better. There was

no factor which could be classified as ”not relevant”,

which means that all factors can be used to build the

model. The standard deviation of the respondents’

statements on factor relevance can also be classified

as appropriate from a statistical point of view. Very

small deviations can be explained by a partially differ-

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

136

entiated understanding of the factors by the experts.

The direction of action of every factor was also

answered in question two, evaluated using the mode

and is shown in table 1 (pos for positive / neg for neg-

ative). The direction of action of the factors provides

information on whether a high level of the factor is

a positive or negative indication of the business pro-

cess’s knowledge intensity under investigation. An

initial analysis of the direction of action was already

carried out during the first three cycles. Expert opin-

ions additionally check these results. For example, a

high standardization ability of a process is evaluated

negatively on its knowledge intensity, which means

that a process with a very high standardization ability

is more likely to be a non-knowledge-intensive busi-

ness process.

Table 1: Directions of effects for every factor.

Nr Factor Effect Weight

PROCESS

1 standardization ability neg 11%

2 formalization ability neg 8%

3 complexity pos 7%

4 needed information pos 7%

5 scope for decision pos 6%

6 malfunction pos 4%

7 degree of structuring neg 2%

PEOPLE

8 knowledge of employees pos 12%

9 expertise pos 9%

10 experience pos 6%

TASKS

11 adaptivity pos 7%

12 flexibility pos 2%

INTERDEPENDENCIES

13 communication pos 11%

14 number of stakeholders pos 6%

15 interfaces pos 2%

The evaluation of question two showed that no ex-

pert developed his own scenario 5, and thus an eval-

uation of the four given scenarios can be made. This

evaluation of the data showed that scenario 3 emerged

as the most frequently chosen scenario. From this

output, two statements can now be set for measure-

ment purposes: (1) It is essential to the experts that

a step-by-step evaluation is carried out at category

level and overall level; (2) The following two restric-

tions can be taken as restrictions for a classification of

a knowledge-intensive business process: (a) at least

50% must be achieved per category and (b) in total at

least 75% of the possible maximum score.

Question 3 on the weighting of the individual cat-

egories was evaluated by the experts as given: (1) pro-

cess = 10%, (2) people = 50%, (3) task = 20% and (4)

interdependencies = 20% . The mode was also used

here as a statistical measure, which is represented in

the form of the percentage values per category. The

evaluation of this question leads to the conclusion that

the human category is the most relevant category for

this model, and the category of formal criteria is clas-

sified as the least relevant category.

Question 4 will be answered with the dedicated

calculation steps that have to be performed and are

given in section 6.

The author will point out that with the knowledge

gained in this work, it will not be possible to achieve

a clear separation between the two poles - thus, with

the help of this model, a direction can be diagnosed,

but no clear and precise separation can be established.

The first step is to look at the processes in a company,

and therefore, a list of all factors is necessary to ap-

ply the measurement model. The determination of the

factors is explained, and an example of the measure-

ment model is shown. In figure 2, the factor analysis

template is given to be filled out by the process eval-

uation responsible.

Figure 2: Measurement Example - Template.

All 15 factors are provided with a scale. This

ranges from ”completely correct” to ”not correct”

with the two intermediate steps ”partially correct” and

”not correct at all”. This type of scale has been used

because it has proved to be successful in practice to

use scales with an even number of scores. After all,

this forces the respondent to make a statement in one

A Measurement Model to Identify Knowledge-intensive Business Processes in SMEs

137

direction. An alternative would be to use a scale with

an odd number of values, but which would then allow

the middle to be selected. However, since the present

study is a classification in the sense of ”Yes - the

process will be rather knowledge-intensive” or ”No -

the process will be rather non-knowledge-intensive”,

a selection of four points is preferred. The determi-

nation of the factor characteristics can then be carried

out. For each factor, its value is entered, and thus

the values of all factors for a process are recorded.

The respective values are converted using the coding

schemes listed in table 2. It is essential to differentiate

the influence concerning the direction of action.

Table 2: Coding of the scale.

effect entirely partly hardly not

true true true applicable

pos. 3 2 1 0

neg. 0 1 2 3

The assumption that the conversion sequence is

reversed in the case of an adverse effect relationship

can be explained by the fact that conversion by a

change of sign would influence the calculation, but

this does not describe the directional effect. It is,

therefore, merely a matter of including the opposite

direction as positive overall. This also offers the pos-

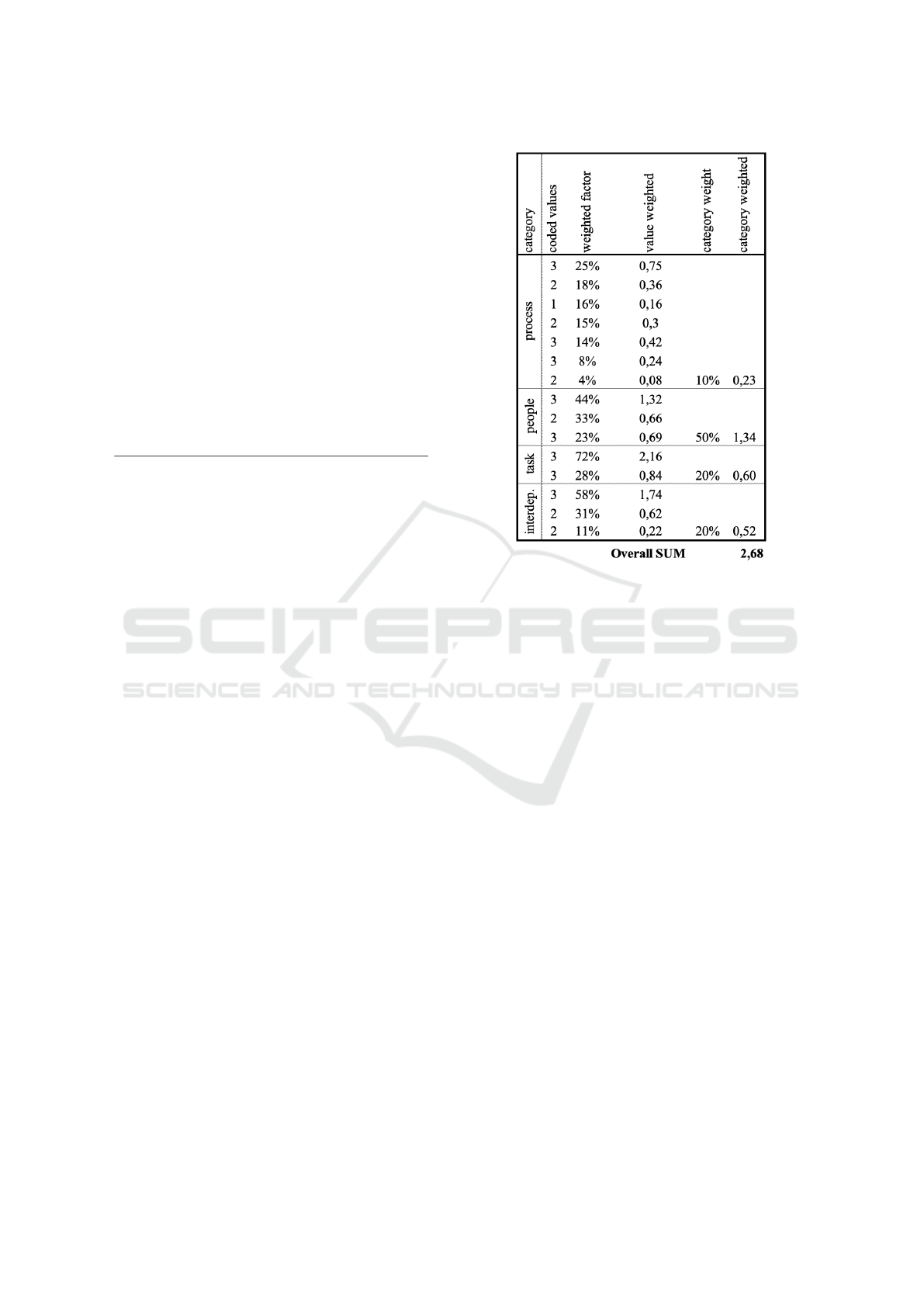

sibility to carry out the calculation relatively easily,

either manually or computer-aided. The weight of the

factor was mentioned in figure 3 and are combined

with the information given in table 2 per factor and

summed up per category. The last step is to rank the

categories sum and build an overall sum for this, re-

markably measured process, as shown in figure 3.

6 CONCLUSION

Knowledge management and business process man-

agement are not only theory-based concepts from sci-

ence but also practical possibilities to improve enter-

prises’ efficiency through the application orientation

of business informatics as a research discipline. In re-

cent years, it has also been recognized that combining

the two concepts, in the form of knowledge-intensive

business processes, can achieve specific synergy ef-

fects (Remus, 2002).

It is precisely these synergy effects that can also be

very beneficial for the long-term survival of a particu-

lar group of companies: small and medium-sized en-

terprises. This group of enterprises, with their specific

requirements that must be differentiated from those

of large enterprises, is mostly left out of the current

discussion about knowledge-intensive business pro-

Figure 3: Measurement Example - Calculation.

cesses. The present work is to be classified precisely

in this minimal researched area of business informat-

ics. The aim was to develop a model for the diagnos-

ing knowledge-intensive business processes in SMEs,

whereby the diagnosis can be understood as the de-

termination, examination, and classification of factors

with the aim to split the whole process landscape in

knowledge-intensive ones with a ranking and all the

others to focus on the knowledge-intensive ones first

if it comes to project management initiatives regard-

ing the fulfillment of quality management norms.

To perform this differentiation, the following steps

have to be performed for every process:

1. take the measurement template as given in figure

2 to evaluate the factors of a particular process

2. combine the information of the scale with the pos-

itive or negative coding given in table 1 and mul-

tiply that with the weight of the factor

3. take the sum of the values weighted and multiply

that with the category weight given in the answer

of question 3 and shown in the example in figure

3 - this leads to the category weighted values

4. sum up the category weighted and this represents

the overall rating of the particular process

5. redo the given steps for all processes in the land-

scape, take the two formulated restrictions into

consideration and build a ranking of all your busi-

ness processes

KMIS 2020 - 12th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

138

Following all given five steps after the application of

this measurement model, a company gets a structured

overview of their more and less knowledge-intensive

business processes to get an idea with which pro-

cesses to start the improvements according to any pro-

cess management initiatives or the application of a

quality management norm.

7 LIMITATION AND OUTLOOK

There is one obvious limitation to this presented

study: the missing application of the measurement

model in practice. The author tried to implement all

the necessary knowledge from practitioners and com-

bined it with a scientific background, but there is a

lack of practical evidence which should be improved

by the next step in this research project.

The next goal is to specify the lack of calibration

of the factors/restrictions and to substantiate this uti-

lizing additional studies. In this context, the diagnos-

tic model should be applied in companies, and a sec-

ond measurement should be carried out using other

methods. The two results can then be compared with

each other, and new insights can be gained to improve

the measurement ability and prove the whole concept.

REFERENCES

Allweyer, T. (1998). Modellbasiertes wissensmanagement.

Information Management, 13(1):37–45.

Carroll, J. M. and Swatman, P. A. (2000). Structured-case:

a methodological framework for building theory in in-

formation systems research. European journal of in-

formation systems, 9(4):235–242.

Davenport, T. and Prusak, L. (2000). Working knowledge:

How organizations manage what they know. Ubiquity,

2000(August):6.

Delahaye, B. (2003). Knowledge management in an sme.

International Journal of Organisational Behaviour,

9(3):604–614.

Desouza, K. C. and Awazu, Y. (2006). Knowledge manage-

ment at smes: five peculiarities. Journal of knowledge

management.

Dumas, M., La Rosa, M., Mendling, J., and Reijers, H. A.

(2013). Business process management. Springer.

Dunkelberg, W. and Wade, H. (2007). Overview–small

business optimism. Small Business Economic Trends,

pages 1–21.

Durst, S. and Edvardsson, I. (2012). Knowledge manage-

ment in smes: a literature review. Journal of Knowl-

edge Management.

Edwards, J. S. and Kidd, J. B. (2003). Bridging the gap

from the general to the specific by linking knowledge

management to business processes. In Knowledge and

business process management, pages 118–136. IGI

Global.

Eppler, M. J., Seifried, P., and R

¨

opnack, A. (2008). Improv-

ing knowledge intensive processes through an enter-

prise knowledge medium (1999). In Kommunikation-

smanagement im Wandel, pages 371–389. Springer.

Goesmann, T. and Hoffmann, M. (2000). Unterst

¨

utzung

wissensintensiver gesch

¨

aftsprozesse durch workflow-

management-systeme. Verteiltes Arbeiten–Arbeit der

Zukunft. Tagungsband der D-CSCW 2000.

Gronau, N., M

¨

uller, C., and Korf, R. (2005). Kmdl-

capturing, analysing and improving knowledge-

intensive business processes. J. UCS, 11(4):452–472.

Heinrich, L. J., Heinzl, A., and Roithmayr, F. (2014).

Wirtschaftsinformatik Lexikon. Walter de Gruyter

GmbH & Co KG.

Helfferich, C. (2011). Die qualit

¨

at qualitativer daten.

Maier, R. and Thalmann, S. (2007). Describing learning

objects for situation-oriented knowledge management

applications. In 4th Conference on Professional Kon-

wledge Management Experiences and Visions, vol-

ume 2, pages 343–351.

McAdam, R. and Reid, R. (2001). Sme and large organisa-

tion perceptions of knowledge management: compar-

isons and contrasts. Journal of knowledge manage-

ment.

Mentzas, G., Apostolou, D., Young, R., and Abecker, A.

(2001). Knowledge networking: a holistic solution for

leveraging corporate knowledge. Journal of knowl-

edge management.

Mertins, K., Heisig, P., Vorbeck, J., Mertins, K., Heisig,

P., and Vorbeck, J. (2001). Knowledge management:

Best practices in europe.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1998). A theory of the firm’s

knowledge-creation dynamics.

Oesterle, H. and Winter, R. (2000). Business engineering.

In Business Engineering, pages 3–20. Springer.

Ploder, C. and Kohlegger, M. (2018). A model for data

analysis in smes based on process importance. In In-

ternational Conference on Knowledge Management in

Organizations, pages 26–35. Springer.

Probst, G., Raub, S., and Romhardt, K. (2006). Wissen man-

agen. Springer.

Remus, U. (2002). Prozessorientiertes Wissensmanage-

ment. Konzepte und Modellierung. PhD thesis.

Richter-von Hagen, C., Ratz, D., and Povalej, R. (2005). A

genetic algorithm approach to self-organizing knowl-

edge intensive processes. In Proceedings of I-KNOW,

volume 5. Citeseer.

Saloj

¨

arvi, S., Furu, P., and Sveiby, K.-E. (2005). Knowledge

management and growth in finnish smes. Journal of

knowledge management.

Senge, P. M. (1996). Die fuenfte disziplin: Kunst und praxis

der lernenden organisation, 2. Aufl., Stuttgart.

Skyrme, D. J. (1998). Measuring the value of knowledge.

Business Intelligence.

A Measurement Model to Identify Knowledge-intensive Business Processes in SMEs

139