Consumers’ Expectation towards Functional Foods:

An Exploratory Study

I Gede Mahatma Yuda Bakti, Sik Sumaedi, Nidya J. Astrini, Tri Rakhmawati and Medi Yarmen

Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Expectation, Consumers, Functional Foods, Exploratory.

Abstract: There are various functional foods offered in the market in the forms of food and beverage. Unfortunately,

not all of them survived. Many functional food products had been rejected by consumers because they did not

focus on consumers’ expectation. This research has one main purpose: to investigate consumers’ expectations

towards functional foods’ health benefits. Three research methods were employed; literature review, multiple

interviews, and a survey. The interview data were analyzed using thematic analysis method while the survey

data was assessed using Exploratory Factor Analysis. Cronbach’s Alpha and the calculation of indicator

transformation index were also employed. The research identified 22 important expectations related to

functional foods’ health benefits. This result is beneficial for companies in creating consumers’ oriented

functional foods. It can also serve as an input for the government in establishing functional food development

policy.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the industry sectors that is currently enjoying

significant growth in the global market is the food

industry. It is because this industry provides a basic

need, but also products that have potential

physiological benefits for their consumers (Bachl,

2007; Chrysochou, 2010; Pech-Lopatta, 2007;

Goetzke & Spiller, 2014). The term is “functional

food.” Generally, functional food products are “foods

that may provide health benefits beyond basic

nutrition” (Roberfroid, 2000).

On the other hand, consumers awareness of a

healthy lifestyle and the prevalence of non-

communicable diseases (NCDs) also rises (Zoltan et

al., 2012; La Barbera, 2016). This is due to the rising

health costs of treating NCDs (Peake, 2001).

Consequently, the demand for functional foods

upsurges ever year. It can be seen from 7-10% annual

growth of the functional food industry (Fitzpatrick,

2003). This growth is expected to persist in the future

(Westrate et al., 2002; Black & Campbell, 2006;

Verbeke, 2006; Kljusuric et al., 2015). Furthermore,

the functional food market share was projected

between $11 to $155 billion per year (Doyon, 2008).

Even though the functional food industry shows a

positive trend, there were many companies that failed

marketing their products. One of the reasons was

consumers did not accept the products even though

they gave health benefits. It happened because there

were expectancy discrepancies between companies

and consumers (Parasuraman et al., 1985). In other

words, the health benefits offered by the products

were not the ones expected by the consumers or

consumers had different expectations regarding the

health benefit of functional food.

In the consumer behavior literature, one of the

concepts that have been studied and discussed

multiple times by researchers theoretically and

practically was consumers’ expectation (Licata et al.,

2008). This was because ‘expectation’ was one of the

determinants of consumers acceptance. Previous

researchers stated that consumers’ expectation was

closely related to product quality (Ignacio et al., 2006;

Brunso et al., 2002; Issanchou, 1996; Douglas &

Connor, 2003). Other researchers added that

‘expectation’ also related to consumers satisfaction

(Cadotte et al., 1987; Bhattacherjee, 2001; Yi, 1993).

Even though consumers expectation has an

important role in product success, this study argues

that previous research on consumers expectation

toward the health benefit of functional food has not

been widely discussed. Research in the context

Indonesian consumers, who are very likely different

from other consumers, are even rarer. Different

Bakti, I., Sumaedi, S., Astrini, N., Rakhmawati, T. and Yarmen, M.

Consumers’ Expectation towards Functional Foods: An Exploratory Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0009993300002964

In Proceedings of the 16th ASEAN Food Conference (16th AFC 2019) - Outlook and Opportunities of Food Technology and Culinary for Tourism Industry, pages 37-43

ISBN: 978-989-758-467-1

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

37

dietary habits, climate, vegetation, economic

condition, and population distribution influence

consumers expectation (Kljusuric et al., 2015).

Related to that condition, a study to investigate

consumers expectation toward functional foods

health benefits in the context of Indonesia becomes

important. This study expects to give inputs for

businesses in developing consumers expectation-

oriented products.

1.1 Functional Food

Even though studies on functional foods have

significantly grown, agreed-upon definition of

functional food does not exist, yet (Sarkar, 2019).

Several organizations and researchers might have

different definitions. The International Life Sciences

Institute defines functional food as foods that, by

virtue of the presence of physiologically-active

components, provide a health benefit beyond basic

nutrition (ILSI, 1999). According to International

Food Information Council, functional foods are foods

(or beverages) that provide health benefits beyond

basic nutrition, like improving the diets or reducing

the risk of specific diseases (IFIC, 2009). In

Indonesia, Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan

(National Agency of Drug and Food Control or

BPOM) defined functional foods as “processed foods

with one or more food components, which based on

scientific research have a certain physiological

function beyond their basic function, do not pose

harmful effects and contain health benefits” (BPOM,

2011). However, BPOM retracted that definition. A

researcher defined functional foods as “food that

encompasses potentially helpful products, including

any modified food or food ingredient that may

provide a health benefit beyond that of the traditional

nutrient it contains” (Roberfroid, 2000). Another

researcher defined it as “a food and not a drug, that is

part of a normal diet, and that can produce benefits

beyond basic nutrition” (Lajolo, 2002). On the other

hand, functional food is defined as “any substance

that is a food or part of a food that provides medical

and/or health benefits, including the prevention and

treatment of disease” (DeFelice, 2007). From those

definitions, it was clear that functional foods are not

regular foods because they provide not only basic

nutrition but also an extra health benefit. Based on

that definition, there are several types of functional

foods, which are fortified food, enriched food, altered

food, and enhanced commodities (Kotilainen et al.,

2006; Spence, 2006; Siro et al., 2008). The definitions

can be seen in table 1.

Table 1: Types of functional foods.

No

Type of

functional

foods

Definition

1 Fortified food “A food fortified with

additional nutrients”

2 Enriched food “A food with added new

nutrients or components not

normally found in a

p

articular food”

3 Altered food “A food from which a

deleterious component has

been removed, reduced or

replaced with another

substance with beneficial

effects”

4 Enhanced

commodities

“A food in which one of the

components has been

naturally enhanced through

special growing

conditions, new feed

composition, genetic

mani

p

ulation, or otherwise”

Source: Siro et al., 2008.

1.2 Consumer Expectation

In the consumer behavior literature, there is not a

converged definition of consumer expectation.

According to the study of Santo and Boote (2003), the

definitions could be categorized into nine groups,

which are (1) expectation as the ideal standard (what

the consumer wished for the excellence-performance

of product), (2) expectation as ‘should be’ standard

(what the consumer feels ought to happen), (3)

expectation as the desired standard (what the

consumer wants to happen), (4) expectation as the

predicted standard (what the consumer thinks will

happen), (5) expectation as the deserved standard

(consumers’ subjective evaluation of their own

product investment), (6) expectation as the adequate

standard (the lower level expectation for the threshold

of acceptable product or service), (7) expectation as

the minimum tolerable (the lower level or bottom

level of performance acceptable to the consumer), (8)

expectation as the intolerable (under the minimum

tolerable level of expectation), and (9) expectation as

the worst imaginable (the lowest level of

expectation).

This study refers to ‘consumer expectation’ as an

ideal expectation or an ideal need and want that is

expected by the consumer toward the performance of

functional foods. This study adopted that definition

because ‘ideal expectation’ was not affected by

various marketing variables and the competition, so it

is suitable for this research (Santos & Boote, 2003).

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

38

In addition, ‘ideal expectation’ was also believed to

be stable from time to time compared to ‘consumer

expectation’ as a ‘should be’ standard (Churchill,

1979).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is exploratory research with a quantitative

approach. To achieve the aim of this research, this

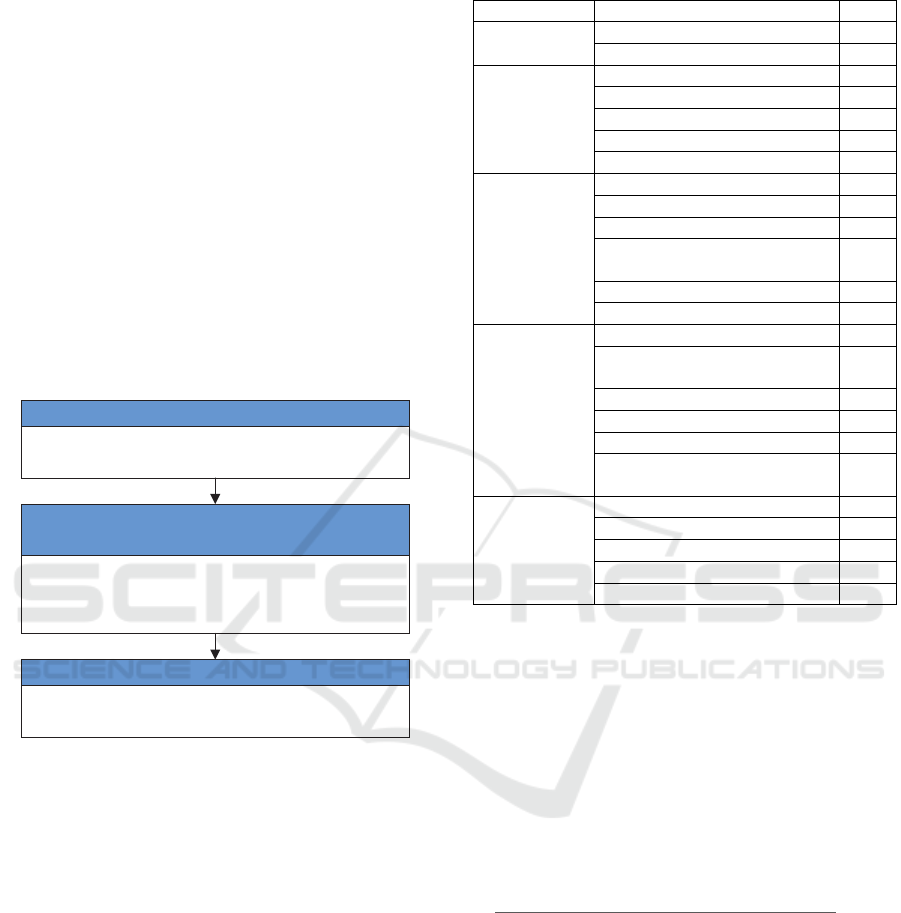

study went through three stages (see figure 1). First,

this study investigated consumers’ expectation

toward functional foods. In this stage, this research

conducted a literature review of previous studies that

focused on the health benefits of functional foods.

This study also ran interviews on several consumers

to ask about their expectations that might have (or

have not been) identified by previous research.

Purpose: Identifying consumer expectation

Method: Literature review and exploratory interviews

Step 1. Investigating Consumer Expectation

Purpose: Reducing the number of expectations

Method: Survey using questionnaires, Exploratory Factor

Analysis, Cronbach’s α

Step 2. Determining and Categorizing Consumer

Expectation

Purpose: Assessing the consumer expectations

Method: Survey using questionnaires

Step 3. Measuring the Value of Each Expectation

Figure 1: Research process.

The second stage aims to determine and

categorize consumers expectation. This stage

determined which kind of health benefits that were

direly expected by functional food consumers.

Specifically, this stage omitted benefits that were not

expected by consumers. After the determination,

health benefits were then statistically categorized to

help businesses in understanding consumers

expectation. For this stage, this study conducted a

survey to gather data using a questionnaire. The

questionnaire inquired about how high their

expectations are. This questionnaire used a 5-point

Likert scale to represent consumers expectation. The

survey was done in three areas, which were Jakarta,

Bekasi, and Tangerang. The respondents were

Indonesian aged 18 and above and chosen based on

convenience sampling. This study used 114

respondents, which profile can be seen in table 2. The

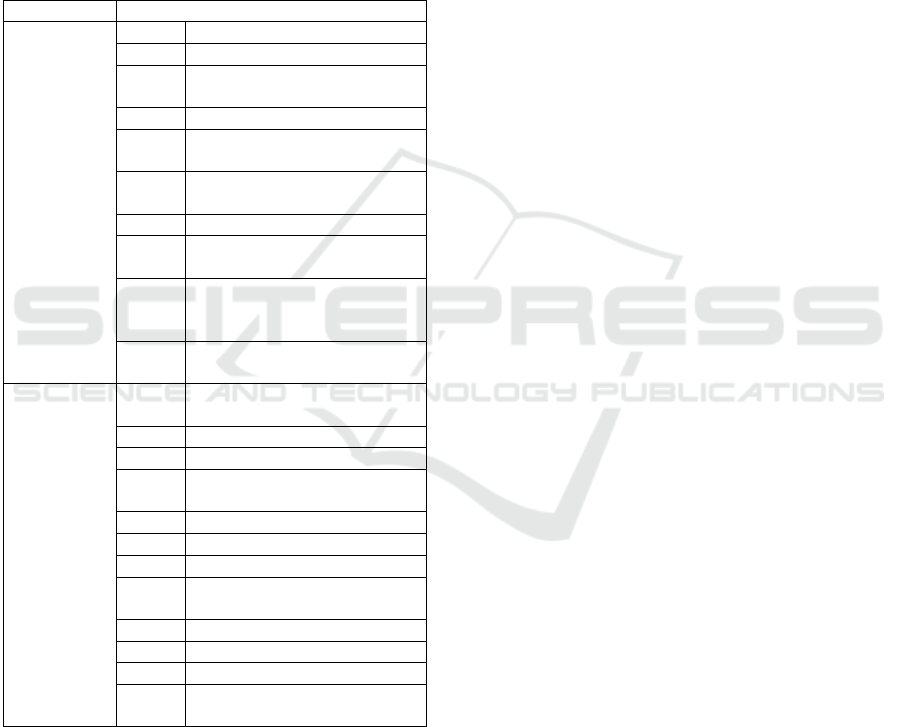

Table 2: Demographic profile.

Characteristic Cate

g

ories %

Sex

Male 97.4

Female 2.6

Age

≤ 20 years ol

d

0.9

21

–

30 years ol

d

23.7

31

–

40 years ol

d

45.6

41

–

50

y

ears ol

d

26.3

≥ 51

y

ears ol

d

3.5

Education

Primar

y

school 1.8

Junior high school 10.5

High school 77.2

College diploma/bachelor’s

degree

5.3

Bachelor’s degree (Hons) 4.4

Master’s degree 0.9

Occupation

Unem

p

lo

y

ed 0.9

Stay-at-home (without

income)

58.8

Freelancers 8.8

Student 0.9

Entre

p

reneu

r

6.1

Permanent employee of

p

rivate business

24.6

Monthly

income

No income 7.0

≤R

p

2.500.000 3.5

Rp2.500.001 - Rp5.000.000 71.9

Rp5.000.001

–

Rp10.000.000 14.9

> Rp10.000.000 2.6

statistical analyses used in this stage were

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Cronbach’s

alpha (α).

After being identified and categorized, the list of

expectations was measured to determine which the

most expected health benefits were in the third stage.

This stage aims to investigate consumers priorities.

The technique used in this stage was the Indicator

transformation index. The formula is below (Aminah

et al., 2015).

Transformation Index

x100

This study used three categories: low expectation

(0-59), moderate expectation (60-80), and high

expectation (81-100) (Afina & Retnaningsih, 2018).

3 RESULTS

3.1 List of Consumers’ Expectation

The exploration of consumers’ expectation has been

done through literature review and interviews. A

Consumers’ Expectation towards Functional Foods: An Exploratory Study

39

review was done to previous studies that focused on

the health benefits of functional foods (Schnettler et

al., 2015; Siegrist et al., 2009; CMPA, 2003). After

that, interviews with 11 consumers were done to gain

an in-depth understanding of their expectations,

which might not have been identified through the

review. This study found 22 health benefits expected

from functional foods. Those expectations were then

divided into two categories, which were ‘disease

prevention’ and ‘improvement of bodily functions.’

The list is displayed in table 3.

Table 3: Consumers’ expectations.

Categories Consumers’ expectation

Disease

prevention

CE1 Reducin

g

the risk of diabetes

CE2 Reducin

g

the risk of cance

r

CE3 Reducing the risk of heart

disease

CE4 Reducin

g

the risk of stroke

CE5 Reducing the risk of kidney

failure

CE6 Maintaining an ideal level of

b

lood

p

ressure

CE7 Lowering the cholesterol level

CE8 Maintaining a healthy level of

tri

g

l

y

ceride

CE9 Strengthening joints and bones

(including reducing the risk of

osteoporosis)

CE10 Reducing the risk of digestive

diseases

(

colon, stomach

)

Improvement

Bodily

Functions

CE11 Reducing weight problems

(overweight/obese/underweight)

CE12 Preventin

g

earl

y

a

g

in

g

CE13 Im

p

rovin

g

g

eneral stamina

CE14 Improving concentration

(

memor

y)

CE15 Reducin

g

stress/relaxin

g

CE16 Im

p

rovin

g

immunit

y

CE17 Improving sexual performance

CE18 Maintaining healthy skin, nails,

and hai

r

CE19 Maintainin

g

motor

p

erformance

CE20 Maintaining eye functions

CE21 Increasing muscle

CE22 Maintaining a longer feeling of

satiet

y

3.2 Tested List of Expectation and the

Categorization

Based on the EFA, this study found that the

expectation model built by this study is fit. This can

be indicated by the Keiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) of

sampling adequacy value that fell above the cut of

value of 0.5. and the p-value of Bartlett test of

sphericity of lower than 0.05 (see table 4) (Hair et al.,

2010). The analysis also showed that all health

benefits in the ‘disease prevention’ and ‘improvement

of bodily function’ categories were expected. No

health benefit was omitted from the original list

because (1) the MSA value for each health benefit

was above 0.5; (2) their communalities values were

higher than 0.4; and (3) their factor loadings were also

higher than 0.5 (Hair et al., 2010). Aside from that,

the EFA result shows that all health benefits in each

category were proven to be converged into one factor.

The total variance explained for ‘disease prevention’

was 56.974% and 59.341% for ‘improvement of

bodily function.’ The Cronbach’s α coefficient for

‘disease prevention’ was 0.915 and for ‘improvement

of bodily function’ was 0.937. The values were far

higher than the cut-off value of 0.6 (Hair et al., 2010).

Therefore, this research shows that the model to

measure functional food consumers’ expectation was

reliable for both ‘disease prevention’ aspect and

‘improvement of bodily function’ aspect.

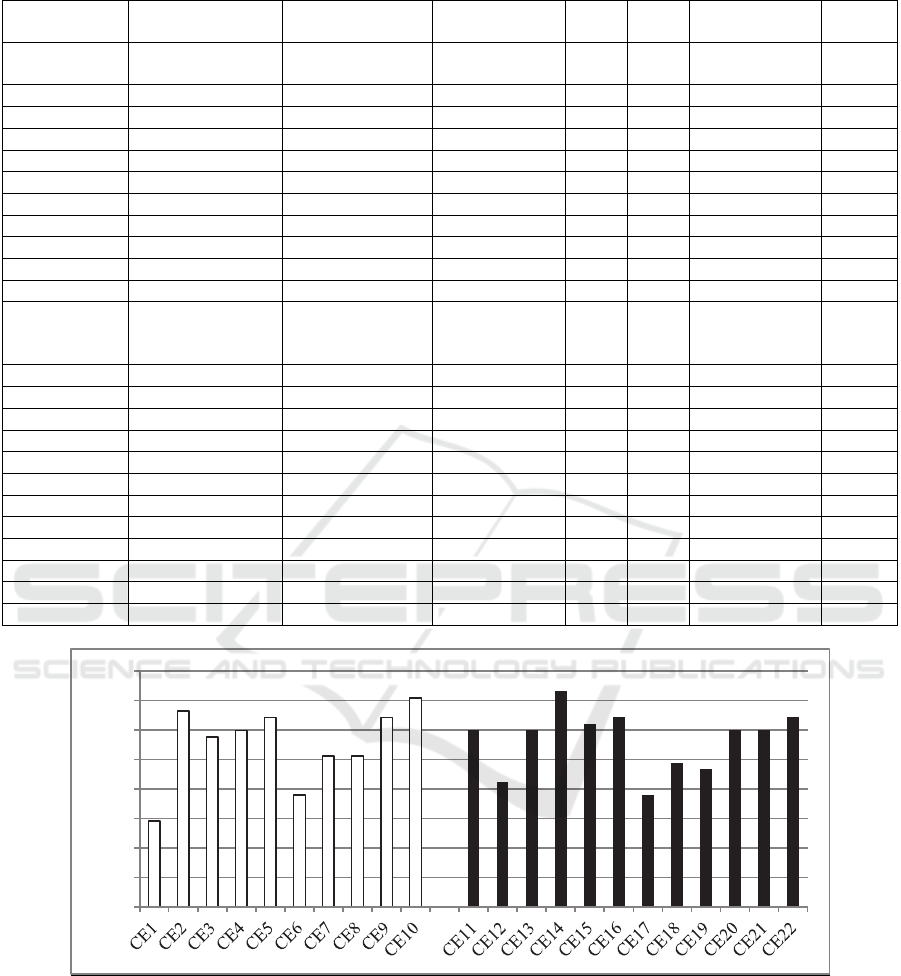

3.3 Indicator Transformation Index

From the previous stage, this study has found 22

consumers’ expectations toward health benefits of

functional foods. Based on the measurement process,

there was only one expectation that generated an

index between 60-80 and the rest have index values

more than 80. This indicates that consumers have

high expectations of 21 health benefits. In the disease

prevention group, three most prioritized benefits were

reducing the risk of contracting digestive diseases

(85.09), reducing the risk of cancer (84.65),

strengthening joints and bones (84.43), reducing the

risk of kidney failure (84.43). In the improvement of

bodily functions group, three most prioritized health

benefits were improving concentration (85.31),

improving immunity (84.43), and maintaining a

longer feeling of satiety (see figure 2).

4 DISCUSSION

This research found that consumers expect 22 health

benefits from various range of functional foods.

There were ten health benefits that represented

‘disease prevention’ and twelve that represented

‘improvement of bodily function.’ This research

supports previous studies that also found similar

categories.

(e.g., Verschuren, 2002; Schnettler et al.,

2015). ‘Disease prevention’ is a health benefits group

that consumers expected to get after consuming foods

or

beverages with disease prevention claim

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

40

Table 4: The results of exploratory factor analysis and Cronbach’s α.

Consumer

expectation

KMO of sampling

adequac

y

Bartlett’s Test of

Sphericity (Sig.)

Total Variance

Explained (%)

CA MSA Communalities

Factor

loading

Disease

Prevention

0.898 635.449 (0.000) 56.974 0.915

CE1 0.932 0.654 0.809

CE2 0.899 0.462 0.680

CE3 0.937 0.464 0.681

CE4 0.868 0.591 0.769

CE5 0.877 0.641 0.801

CE6 0.832 0.479 0.692

CE7 0.895 0.567 0.753

CE8 0.899 0.573 0.757

CE9 0.945 0.623 0.789

CE10 0.901 0.643 0.802

Improvement

Bodily

Functions

0.927 875.090 (0.000) 59.341 0.937

CE11 0.940 0.606 0.779

CE12 0.940 0.622 0.788

CE13 0.934 0.591 0.769

CE14 0.928 0.571 0.756

CE15 0.948 0.609 0.780

CE16 0.950 0.530 0.728

CE17 0.927 0.571 0.756

CE18 0.906 0.531 0.729

CE19 0.902 0.574 0.757

CE20 0.894 0.649 0.806

CE21 0.911 0.650 0.806

CE22 0.948 0.617 0.786

Figure 2: Consumers’ expectation of health benefits offered by functional foods.

(Schnettler et al., 2015). This study found that the

most expected health benefits related to disease

prevention were (1) reducing the risk of digestive

diseases; (2) reducing the risk of cancer; and (3)

strengthening joints and bones. ‘Improvement of

bodily function’ is a group of health benefits expected

by consuming functional foods with bodily functions

improvement claims (Schnettler et al., 2015). This

research identified three most expected health

benefits in terms of the improvement of bodily

functions, which were (1) improving concentration;

(2) improving immunity; and (3) maintaining the

feeling of satiety. This research also revealed that

consumers’ values ‘disease prevention’ and

‘improvement of bodily functions’ equally.

84,65

84,43 84,43

85,09

85,31

84,21

84,43 84,43

78,00

79,00

80,00

81,00

82,00

83,00

84,00

85,00

86,00

Consumers’ Expectation towards Functional Foods: An Exploratory Study

41

This study has practical implications. First, the

result encourages business to understand their

consumers’ expectation while developing a

functional food product. Especially the expectation of

real health benefits in terms of disease prevention or

the improvement of bodily functions. Second, this

study emphasizes that in developing a functional food

product, businesses must decide whether they would

position their products as disease prevention products

or bodily functions improvement products. This study

has identified ten health benefits of functional foods

related to disease prevention and twelve health

benefits related to the improvement of bodily

functions. Those 22 expectations could be a guide for

business in developing functional foods. By adhering

to those expectations, the developed product is

expected to be accepted by consumers and

simultaneously create satisfaction.

Even though this study has generated interesting

findings, it still has limitations. First, the respondents

who engaged in this study were chosen based on

convenience sampling. Consequently, the results

could not be widely generalized. Future research

should use a probability sampling technique. Second,

this study only considered consumers expectation of

health benefits. In reality, when a consumer bought or

consumed certain product, there were many aspects

that played into considerations, such as price, brand,

packaging, etc. Future research should incorporate

other factors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is funded through Insentif Riset Sistem

Inovasi Nasional (National Research Innovation

System Incentive) The Ministry of Research and

Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia. All

authors are main contributor.

REFERENCES

Afina, S. Retnaningsih, R., 2018. The influence of students’

knowledge and attitude toward functional foods

consumption behavior. Journal of Consumer Sciences,

3(1): 1-14.

Aminah S., Sumardjo, Lubis D. P., Susanto D., 2015.

Factors affecting peasants’ empowerment in West

Halmahera District – a case study from Indonesia.

Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the

Tropics and Subtropics, 116(1): 11-25.

Bachl, T., 2007. Wellness trend benefits markets. in BVE

(Ed.). Consumers’ Choice ’07. Berlin, 9-12.

Bhattacherjee, A., 2001. Understanding Information

Systems Continuance: An Expectation–Confirmation

Model. MIS Quarterly, 25(3): 351-370.

Black, I., Campbell, C., 2006. Food or medicine. Journal of

Food Products Marketing, 12(3): 19-27.

BPOM. Peraturan Kepala Badan Pengawas Obat dan

Makanan RI No HK.03.1.23.11.11.09909 Tahun 2011

Tentang Pangawasan Klaim Dalam label dan Iklan

Pangan Olahan.

Brunso, K., Fjord, T. A. Grunert, K., 2002. Consumers’

food choice and quality perception. Working Paper No.

77. The Aarhus School of Business. Aarhus.

Cadotte, E. R., Woodruff, R. B., Jenkins, R. L., 1987.

Expectations and Norms in Models of Consumer

Satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 24: 305-

314.

Chrysochou, P., 2010. Food health branding: the role of

marketing mix elements and public discourse in

conveying a healthy brand image. Journal of Marketing

Communications, 16(1-2): 69-85.

Churchill, G., Jr., 1979. A paradigm for developing better

measures of marketing constructs. Journal of

Marketing Research, 11: 254-260.

CMPA, 2003. Reporting of Diet, Nutrition and Food Safety

(1995-2003). Center for Media and Public Affairs.

Washington.

DeFelice, S., 2007. DSHEA Versus NREA (The

Nutraceutical Research and Education Act) and the

Three Nutraceutical Objectives. The Foundation for

Innovation of Science in Medicine. Commentaries.

Douglas, L. Connor, R., 2003. Attitudes to service quality

– the expectation gap. Nutrition & Food Science, 33(4):

165-172

Doyon, M., Labrecque, J., 2008. Functional foods: a

conceptual definition. British Food Journal, 110(11):

1133-1149.

Fitzpatrick, K., 2003. Functional foods and nutraceuticals:

exploring the Canadian possibilities. Research Report.

University of Manitoba. Winnipeg.

Goetzke, B. I., Spiller, A., 2014. Heavlth-improving

lifestyles of organic and functional food consumers.

British Food Journal, 116(3): 510-526.

Hair, J. F. Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., 2010.

Multivariate data analysis. Prentice- Hall. New Jersey,

7

th

edition.

IFIC, 2009. Functional foods now. International Food

Information Council. Washington, DC.

Ignacio, A., del Bosque, R., Martin, H. S., Collado, J., 2006.

The role of expectations in the consumer satisfaction

formation process: Empirical evidence in the travel

agency sector. Tourism Management, 27: 410-419.

ILSI, 1999. Safety assessment and potential health benefits

of food components based on selected scientific

criteria. Critical Reviews in Food Science Nutrition, 39:

203-316.

Issanchou, S., 1996. Consumer expectations and

perceptions of meat and meat product quality. Meat

Science, 43(1): 5-19

Kljusuric, J. G., Čačić, J., Misir, A., Čačić, D., 2015.

Geographical region as a factor influencing consumers’

16th AFC 2019 - ASEAN Food Conference

42

perception of functional food – case of Croatia. British

Food Journal, 117(3): 1017-1031.

Kotilainen, L., Rajalahti, R., Ragasa, C., Pehu, E., 2006.

Health enhancing foods: Opportunities for

strengthening the sector in developing countries.

Agriculture and Rural Development Discussion Paper

30. Agriculture & Rural Development Derpartment –

World Bank. Washington, DC.

La Barbera, F., Amato, M., Sannino, G., 2016.

Understanding consumers’ intention and behaviour

towards functionalised food, British Food Journal,

118(4): 885-895.

Lajolo, F. M. 2002. Functional foods: Latin American

perspectives. British Journal of Nutrition, 88(2): S145-

S150.

Licata, J., Chakraborty, G., Krishnan, B., 2008. The

consumer's expectation formation process over time.

Journal of Services Marketing, 22(3): 176-187.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, Valarie A., Berry, Leonard L.,

1985. A Conceptual Model of Service quality and Its

Implications for Future Research. Journal of

Marketing, 49: 41-50.

Peake, H., Stockely, M., Frost, G., 2001. What nutritional

support literature do hospital nursing staff require?,

Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 14(3): 225-

230.

Pech-Lopatta, D., 2007. ‘Wellfood’ – healthy pleasures, in

BVE (Ed.). Consumers’ Choice ’07. Berlin, 23-34.

Roberfroid, M., 2000. Defining functional foods. in Gibson

G. and Williams, C.M. (Eds). Functional foods:

Concept to product. Woodhead. Cambridge, 9 – 29.

Santos, J., Boote, J., 2003. A Theoretical Explanation and

Model of Consumer Expectations, Post-Purchase

Affective States and Affective Behavior. Journal of

Consumer Behavior, 3(2): 142-156.

Sarkar, S., 2019. Potentiality of probiotic yoghurt as a

functional food – a review. Nutrition & Food Science,

49(2): 182-202.

Schnettler, B., Miranda, H., Lobos, G., Sepulveda, J.,

Orellana, L., Mora, M., Grunert, K., 2015. Willingness

to purchase functional foods according to their benefits.

British Food Journal, 117(5): 1453-1473.

Siegrist, M., Stampfli, N. Kastenholz, N., 2009. Acceptance

of nanotechnology foods: a conjoint study examining

consumers' willingness to buy. British Food Journal,

111(7): 660-668.

Siro, I., Kápolna, E., Kápolna, B., Lugasi, A., 2008.

Functional food: product development, marketing and

consumer acceptance - A review. Appetite, 51(3): 456-

467.

Spence, J. T., 2006. Challenges related to the composition

of functional foods. Journal of Food Composition and

Analysis, 19: S4-S6.

Verbeke, W., 2006. Functional foods: consumer

willingness to compromise on taste for health. Food

Quality and Preference, 17(1-2): 126-131.

Verschuren, P. M., 2002. Functional foods: Scientific and

global perspectives. British Journal of Nutrition, 88(2):

S125-S130.

Westrate, J. A., van Poppel, G., Verschuren, P. M., 2002.

Functional foods, trends and future. British Journal of

Nutrition, 88(2): S233-S235.

Yi, Y., 1993. The determinants of consumer satisfaction:

the moderating role of ambiguity. Advances in

Consumer Research, 20: 502–506.

Zoltan, S., Szente, V., Kover, G., Polereczki, Z., Szigeti, O.,

2012. The influence of lifestyle on health behavior and

preference for functional foods. Appetite, 58: 406-413.

Consumers’ Expectation towards Functional Foods: An Exploratory Study

43