False Alarm: Cutaneous Anthrax Suspicion

in a Case of Bullous Erysipelas - The Clinicopathological

Consideration

Randy Satria Nugraha Rusdy

1*

,Teffy Nuary

1

, Sri Linuwih S. W. Menaldi

1

, Rahadi Rihatmadja

1

1

Department of Dermatology and Venereology Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia/

Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo National CentralGeneral Hospital, Indonesia

Keywords: Bullous Erysipelas, Cutaneous Anthrax, Histopathology

Abstract: Erysipelas is acute superficial infection involving the epidermal and dermal layers, which may feature

bullous formation. Bullous erysipelas lesion can mimic Sweet’s syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum and

other skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs). A 42-year-old male presenting with multiple erythematous and

edematous plaques with a large bulla on his left lower leg was first diagnosed clinically with Sweet’s

syndrome or pyoderma gangrenosum. Routine histopathology showed partial epidermal necrosis and

massive dermal edema with neutrophils, lymphocytes and nuclear dust, which might be consistent with the

aforementioned diagnoses. However, taking into account the clinical presentation, the possibility of

cutaneous Anthrax was also raised, especially when the patient was later found to work in areas where

domesticated animals roamed. Further investigation with Gram staining did not demonstrate Gram-positive

bacilli, negating the suspicion. Cefadroxil as prophylaxis which later continued with clindamycin gave

marked improvement. Clinical and histological findings, and response to antibiotics favored bullous

erysipelas as the final diagnosis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Erysipelas is an acute superficial infection and

inflammation of the skin, that features a painful,

warm, erythematous swollen lesion, with sharply

demarcated border. Systemic signs and symptoms

include fever, nausea, vomiting, general weakness,

muscle pain, and lymphedema. (FY Chong et al.,

2008). Usually involving epidermal and dermal

layers, 5% of erysipelas can be complicated by bulla

formation which represents deep seated process,

such as in bullous erysipelas.(S Vichitra et al 2016)

Bullous erysipelas lesions were characterized by

erythematous macules and patches with flaccid

epidermal sterile blister. (S Vichitra et al 2016).

Usually appears on facial areas and legs, they can be

accompanied with necrosis and purpuric hemorrhage

which take longer period of tissue repair.

Not only difficult to treat and related to more

complications, bullous erysipelas with atypical

presentation can mimic other disease, such as

Sweet’s syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, and

other skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) that are

diagnostically challenging. Histopathology

examination shares many similar features among

erysipelas and those diseases, including cutaneous

anthrax. Therefore, clinical recognition coupled with

knowledge of pathology of diseases contribute

greatly to making sound diagnosis. We present a

case of challenging diagnostic approach in a case of

bullous erysipelas that was nearly mistaken for

cutaneous anthrax.

2 CASE

A 42-year-old male came to our department’s

outpatient clinic presenting with several painful

erythematous lesions on the rightlower leg on March

2017.They had appeared since approximately 10

days before. A blister had appeared some days after

and a tentative aspiration was performed at another

hospital. However, the lesion became ulcerated.The

patient was feverish and his lower leg was swollen.

Previous treatment comprised of amoxycillin-

clavulanic acid and non steroidal anti-inflammatory

drug. History of trauma, skin lesion, or application

Rusdy, R., Nuary, T., Menaldi, S. and Rihatmadja, R.

False Alarm: Cutaneous Anthrax Suspicion in a Case of Bullous Erysipelas - The Clinicopathological Consideration.

DOI: 10.5220/0009986602770281

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease (ICTROMI 2019), pages 277-281

ISBN: 978-989-758-469-5

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

277

of substances was denied, as was history of diabetes

mellitus, hypertension, malignancy, alcohol and

smoking. The patient worked in the municipal

sanitary and environmental department, mostly

behind the desk but regularly supervised workers in

the region.

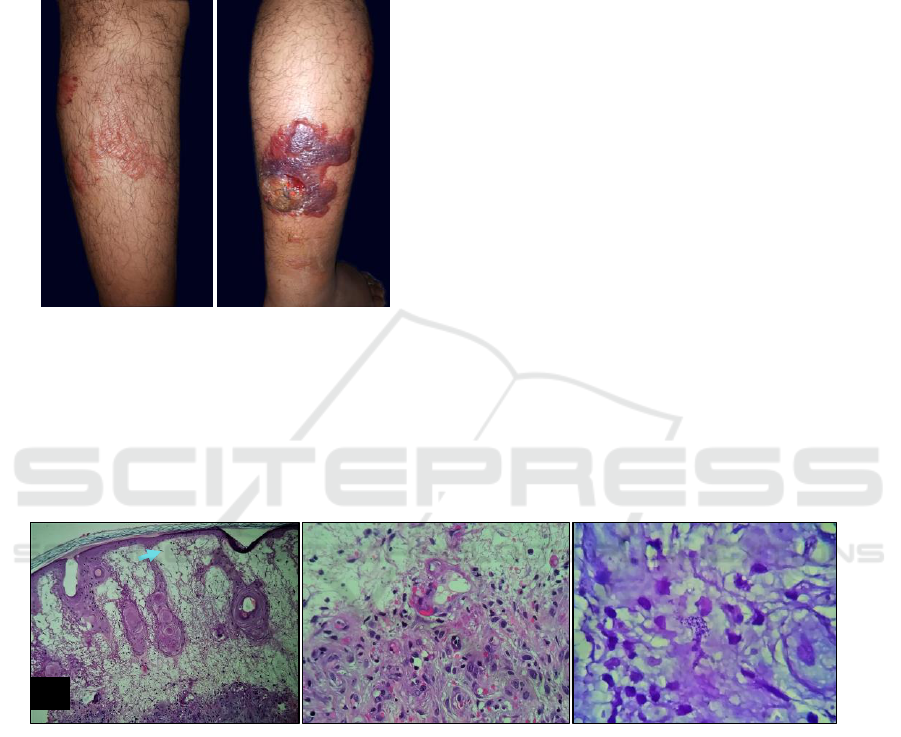

Figure 1.Purpuricand erythematous plaques with a large

hemorrhagic blister on the right lower leg. Swelling was

noted.

There were purpuric and erythematous plaques on

the right lower leg, with extensive edema. A large

hemorrhagic blister was present in the area where a

puncture was previously done. Vital signs and

general physical examination were normal, except

for BMI of 32.92 kg/m

2

. Laboratory result were also

in normal ranges, except increase in erythrocyte

sedimentation rate/ESR (74 mm/hour) and low

eosinophil count (0,9%).Swab from the hemorrhagic

base of the blister showed few Gram-positive cocci

and leukocytes. Aworking diagnosis of Sweet’s

syndrome with differential diagnosis of pyoderma

gangrenosum was made.

Biopsy was performed on two sites, the

erythematous plaque on the anterolateral leg and the

blister margin. Patient received cefadroxil 500 mg

twice a day for a week after biopsy and continued

with clindamycin 300 mg for possible infection.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining from both sites

demonstrated severe upper dermal edema leading to

blister formation, perivascular lymphocytes and

neutrophils, and erythrocyte extravasation. Necrosis

of epidermis and adipocytes in some parts was

noted. These histopathology findings alerted us of

the likelihood of cutaneous anthrax. Patient were

reexamined for possible infection of anthrax. Patient

acknowledged there were many domestic animals

(i.e. goat) where he worked, but no history of direct

contact previously before the lesion appeared. There

was no report of similar casein the environment

where he worked.

Figure 2. A. Marked edema on the upper dermis (blue arrow) and destruction of hair follicles (H&E,100x). B. Infiltrate of

inflammatory cells in dermal layer consisted of neutrophils, lymphocytes, nuclear dusts, and few eosinophils with

endothelial impairment and erythrocytes extravasation (pink arrow) (H&E, 1000x).C. No bacilli were found in Gram stain.

Structures resembled Gram-positive coccus (yellow arrow) sparsely distributed in dermal layer (Gram, 1000x).

Special staining did not reveal Gram-positive

bacilli which did not support diagnosis of cutaneous

anthrax and showed what looked like Gram-positive

cocci, suggesting the more likely cause of infection

for bullous erysipelas.

Ultrasonography by vascular surgeon concluded

lymphedema, although d-dimer and fibrinogen test

result were in normal limits, which did not support

deep vein thrombosis. Patient was suggested to wear

compression stocking. The condition gradually

improved with systemic antibiotics, and additional

treatment with normal saline wet dressing and

sodium fusidic ointment. Clindamycin already given

as prophylaxis and was continued for another two

weeks after biopsy until all lesions resolved and

leaving residual hyperpigmentation. The patient was

finally diagnosed with bullous erysipelas.

A

B

C

ICTROMI 2019 - The 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease

278

Figure 3. Evaluation after biopsy and receiving antibiotics

revealed marked improvement. Erythema and edema

subsided.

3 DISCUSSION

There was slight difficulty in assessing the condition

that we believe was due to non-classical clinical

presentation that might be interpreted as non-

infectious in origin, such as Sweet’s syndrome and

pyoderma gangrenosum. Sweet’s syndrome (SS)

lesion is characterized by tender, glistening

erythematous plaque that gives the impression of

vesiculation, while pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)

may have several variances, including ulceration

with violaceous border. (Cohen PR et al., 2016;

Cowell FC et al., 2008).However, disease history

and clinical data did not support the two entities.

Initially, infection was not considered because

there was no known trauma preceding the lesion.

The lesions appeared abruptly and accompanied by

fever and pain which was first thought to be clinical

manifestation of Sweet’s syndrome. There was

history of blister aspiration which later exacerbated

lesion. Moreover, there was no history of

malignancy, systemic infection, medication, or

inflammatory bowel disease which were usually

found in SS.(Cohen PR et al., 2016).

Pyodermagangrenosum usually occurred in older

people, with various underlying morbidity, that was

still doubtful in our case. Nevertheless, it was

diagnosis of exclusion that required ruling out other

diseases.(Cowell FC et al., 2008).

Regional lymph node enlargement and edema,

however, might suggest underlying infection.

Laboratory result did not support leukopenia and

neutropenia, although there was higher result of

erythrocyte sedimentation rate.(Cohen PR et al.,

2016). Our case showed low neutrophil count which

was not consistent with infection and SS.

Bullous formation, along with abscess,

hemorrhagic purpura and necrotic lesion are major

local complications usually found in erysipelas.

Local complication occurred around 31-52%

patients with erysipelas. It is associated with several

risk factors, including age ≤ 50 years, female gender,

obesity, smoking, history of diabetes mellitus,

hypertension, heart disease, and prior treatment with

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. (Krasagais KI

et al., 2006). A comparison study in 2015 between

erysipelas patients with localized complication and

without showed history of antibiotic before

admission (OR = 5.15) and accelerated erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (OR = 5) as independent risk

factors. (Montravers P et al., 2016). Our case was

obese and had history of short-course amoxicillin-

clavulanic acid and anti-

inflammatorymedication.Possible sources of

infection in erysipelas including leg ulcer,

excoriating skin disease, and ascending infection

from distal limb inoculation, which usually follow

toe-web fungal infection. (Jendoubi F et al., 2019).

Since we did not find any signs mentioned above in

our case, we assumed the more likelihood of

microtrauma as the source of inoculation. As we

could not ascertained the origin of infection in our

case, the diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome was

considered. The ulceration had confused the

diagnosis of erysipelas with pyodermagangrenosum.

Histopathological evaluation unfortunately did

not give conclusive result. The main findings, heavy

neutrophilic infiltrates corresponding with epidermal

necrosis and stark dermal edema, suggestive of

infection, but might also support the provisional

diagnoses.(Johnston RB et al., 2012). Striking

edema and epidermal necrosis combined with

description of blister formation and subsequent

ulceration also alerted us of cutaneous anthrax

possibility. .(Johnston RB et al., 2012). Gram-

positive bacilli, however, was not found.

Blood cultures in bullous erysipelas usually

produce negative result. Culture can be performed

by bacterial swab from the blister or ulcer, even

though there are still more possibilities of negative

finding. (Krasagais KI et al., 2006). performed

culture of bullous erysipelas and find 4 out of 7

patients were sterile. We did not perform it since he

initially was diagnosed as SS and PG.

Reexamination of the patient did not confirm

history of direct contacts with domesticated animals

(i.e. goats) or their products, even though he

acknowledged some of those animals wandered

False Alarm: Cutaneous Anthrax Suspicion in a Case of Bullous Erysipelas - The Clinicopathological Consideration

279

around the neighborhood where he sometimes came

to inspect. To his knowledge, there was no similar

ailment reported from the area or by his co-workers.

Moreover, cutaneous anthrax lesion usually starts

with papule and vesicles distributed on the face or

upper extremities that rapidly breaks down to

necrotic painless ulcer with brawny edges, unlike in

our case. Antigen detection by tissue polymerase

chain reaction (PCR) is highly recommended to

perform if cutaneous anthrax is still suspected.(Titou

H et al., 2012) Suspicion of cutaneous anthrax can

also be excluded by immunohistochemistry,

although it was not available.

Finally, a favorable response toward antibacterial

monotherapy and leg compression as adjuvant

without the need to add systemic corticosteroid has

greatly supported diagnosis of bullous erysipelas.

Erysipelas in general has rapid and favorable

response to antibacterial treatment. Although many

guidelines has been established, treatment of SSTIs

including erysipelas with local complication is still

challenging because there were many variants,

degree and different etiologic agents which

associated with various pathomechanisms of

infections and clinical manifestation.(E Silvano et

al., 2016) Because SSTIs in general usually due to

Gram-positive microorganism, first line

recommended treatment are usually broad spectrum

antibiotics with more susceptibility towards Gram-

positive bacteria, such as β-lactams, cephalosporin

and clindamycin.(Edwards J et al., 2006). However,

many guidelines available do not consider target

population and its geographical differences, which is

related to epidemiology of various bacterial strains

and susceptibility toward certain antibiotics.

7

Clindamycin was chosen to treat this patient due to

its broad-spectrum activity since the infection

covered deeper structures of the skin and its

underlying structures. Clindamycin and several

antibiotics have its antitoxin property that is

beneficial to reduce early release of exotoxins from

Gram-positive microorganism, since toxin

production is associated with streptococcal and

staphylococcal infections. (Montravers P et al.,

2016).Guideline for SSTIs management from

Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)

recommends the use of clindamycin for mild to

moderate erysipelas and other non-purulent

SSTIs.(Stevens DL et al., 2014). Dosage option and

adjustment should be considered based on specific

clinical condition such as renal insufficiency.

4 CONCLUSION

Bullous erysipelas is a skin and soft tissue infection

characterized by blistering and is not an uncommon

entity. However, it may still be unrecognizable if the

source and mode of infection cannot be identified.

Its clinical presentation could mimic other entities,

such as Sweet’s syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum,

and cutaneous anthrax, each with its own

characteristics (e.g. pseudo vesiculation, brawny

edges) and underlying condition that should not be

overlooked. Histopathology may at times show

findings that are indistinguishable so that correlation

with clinical information should always be sought.

REFERENCES

Cohen PR, Honigsmann H, Kurzroc R. Acute febrile

neutrophilicdermatosis (Sweet Syndrome). Goldsmith

LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller A, Leffell D, Wolff

K, eds. 2008. In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General

Medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw Hill;. p. 362-

70.

Cowell FC, Hackett BC, Wallach D.

Pyodermagangrenosum. Goldsmith LA, Katz SI,

Gilchrest BA, Paller A, Leffell D, Wolff K, 2008. eds.

In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine.

8th ed. New York: McGraw Hill;. p.371-9.

E Silvano, Bassetti M, Bonnet E, Bouza E, Chan M,

Simone GD, et al. 2016. Hot topics in the diagnosis

and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Int

J of Antimicrob Agents.; 48(1): 19-26.

Edwards J, Green P, Haase D. 2006. A blistering disease:

bullous erysipelas. CMAJ.; 175 (3): 247.

FY Chong, T Thirumoorthy. Blistering erysipelas: not a

rare entitiy. Singapore Med J. 2008; 49(10): 809-13.

Jendoubi F, Rohde, M, Prinz JC. 2019. Intracellular

streptococcal uptake and persistence: a potential cause

of erysipelas recurrence. Front Med., 6(6): 1-15

S Vichitra, Senanayeke S. 2016. Bacterial skin and soft

tissue infections.AistPrescr.. 39: 159-63.

Krasagakis K, Samonis G,Maniatakis P, Georgala S,

Tosca A. 2006. Bullous erysipelas: clinical

presentation, staphylococcal involvement and

methicillin resistance. Dermatology.; 212(1): 31-5.

Montravers P, Snauwaert A, Welsch C. 2016. Current

guidelines and recommendations for the management

of skin and soft tissue infections. Curr Opin Infect

Dis.; 29(2): 131-8.

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP,

Goldstein EJC, Gorbach SL, et al. 2014. Practice

guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin

and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the

Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect

Dis.; 59(2): e10-52.

ICTROMI 2019 - The 2nd International Conference on Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease

280

Titou H, Ebongo C, Bouati E, Bouil M. 2017. Risk factors

associated with local complications of erysipelas: a

retrospective study of 152 cases. Pan Afr Med J.;

26(66): 1-7

Vesiculobuloous. 2012. reaction pattern.Johnston RB, ed.

In: Weedon's skin pathology essentials. 4th ed.

Elsevier.. p. 129

False Alarm: Cutaneous Anthrax Suspicion in a Case of Bullous Erysipelas - The Clinicopathological Consideration

281