Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export

Nugroho Indrotristanto

1,2

and

Nuri Andarwulan

1,3

1

Directorate of Food Processed Standardization, National Agency for Drug and Food Control,

Jalan Percetakan Negara No 23, Jakarta, Indonesia

2

Department of Food Science and Technology, IPB University, Gedung Fateta, Kampus IPB University,

Dramaga, Bogor, West Java, Indonesia

3

Southeast Asian Food and Agricultural Science and Technology Centre, IPB University, LPPM-IPB University,

Jalan Ulin No 1, Kampus IPB University, Dramaga, Bogor, West Java, Indonesia

Keywords: Food Safety Notifications, Export Refusals, Risk Profile.

Abstract: Notifications due to food safety by importing countries may pose a significant economic burden for exporting

countries, including Indonesia. This review was conducted systematically to list and to identify Indonesian

food commodities notifications, as discussed by published literatures. The study was conducted using a

systematic approach, as recommended by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-

Analyses. Eight of 7,210 research papers were selected due to information on Indonesian exported food

notifications. However, only four papers were included in analysis, due to the availability of quantitative data

on the notifications. There were 17 reports from these institutions included in the analysis. Fishery based fresh

food seems to be the major sources of notification, followed by plant or animal based fresh food, processed

food and minimally processed fresh food. This study result indicates that comprehensive risk profiles may be

developed for foods from fishery and plant or animal based fresh food products. The profiles may aid to

discuss about risk factors contributing food notifications as well as identifying gaps for necessary scientific

researches and/or risk assessments.

1 INTRODUCTION

Food export is an important source of revenue for a

country. However, importing countries may issue

notification to exporting countries if the traded foods

do not meet food safety requirement in importing

countries. The notification may differ in location

where food safety authorities found exported food

which does not meet food safety standards or high-

risk food. The European Union Rapid Alert System

for Food and Feed (EU-RASFF) classified

notifications into several categories. Border rejection

is activated when food safety officials determine

high-risk food in point of entry (EURASFF, 2018).

While, Alert and Information are issued when food

safety officials found the high-risk food in the market

(EURASFF, 2018). News is considered when there is

information on the availability of high-risk food

however it does not fall under Border rejection, Alert

and Information status (EURASFF, 2018).

The United States government has a different type

of notifications. The United Stated Food and Drug

Administration (US-FDA) has authorities to check

food of their concern, not only for food safety

requirements but also indication of food fraud

(Bovay, 2016). Import alert status is given to food

shipments which violate US food safety standards

therefore food authorities may carry out Detention

without Physical Examination for the shipment

(Bovay, 2016; USFDA, 2019a, 2019b). US-FDA

commonly follow up import alert status with rejection

of imported foods eventhough rejection can be

performed without having the status (Bovay, 2016).

The detention is then recorded in a database called

Operational and Administrative System for Import

System or OASIS (Bovay, 2016). Exporting countries

may look for their food refusals from this database,

since US government make it available on-line.

Therefore, stakeholders in exporting countries may

take necessary follow-up actions.

Food safety notifications likely affect

international food trade for both importing countries

and exporting countries. Both producers and

government bear the burden due to notification of

their exported food commodities. Notification, such

Indrotristanto, N. and Andarwulan, N.

Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export.

DOI: 10.5220/0009978800002833

In Proceedings of the 2nd SEAFAST International Seminar (2nd SIS 2019) - Facing Future Challenges: Sustainable Food Safety, Quality and Nutrition, pages 151-165

ISBN: 978-989-758-466-4

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

151

Figure 1: Summary of Literature Selection Processes.

as rejection, would likely have an enormous impact

for the export value which is supposed to be earned

by exported countries. These burdens may arise due

several factors, such as export value loss, handling

cost, liability risk and brand equity losses (GMA,

2011). Jongwanich (2009) studied food detention

cases by US-FDA on 2002, 2003, and 2004 for

determining export value losses divided by detention

numbers. Value exports per detention cases of Asia

countries varied between 0.25 Million (Pakistan) until

6.94 Million (Thailand) USD per year. While, the

burden bear by Indonesia due to detention of food

product was reported over 2 Million USD per case per

year for export value losses only (Jongwanich, 2009).

Therefore, strategic steps should be taken to minimize

the loss due to food notification by importing

countries.

Food safety policy development requires risk

profiling. This profile provides information on

combination of food and its associated hazards

(Cressey, 2014). Risk profiling is one of steps in food

safety risk management. Codex Alimentarius

Comission (CAC) recommends risk management in

establishing food safety policies, which consists of a

preliminary risk management activities, the

evaluation of options for risk management, decision

implementations, and monitoring for the impacts of

the implemented policies (FAO/WHO, 2007). The

development a risk profile is one of several activities

in preliminary risk management activities. By

providing relevant information regarding food and its

associated hazards, a risk profil may assisst policy

makers to formulate such efficient and effective food

safety policies (Cressey, 2014). Risk profiling may

also provide information on immediate actions as

well as gaps for necessary research and risk

assessments (Cressey, 2014).

The objective of this review is to list and to

identify Indonesian food commodities notifications.

Futhermore, the associated hazards, which cause food

notification are also identified. This study uses a

systematic review approach, which includes

determining, selecting, and analyzing data of related

literature (Moher et al., 2009). The identified food

and its associated hazards may be a valuable source

of information in selecting food commodities for risk

profiling.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Search Strategies

Literature searching was conducted systematically

using an approach recommended by Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-

Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009). The

searching was conducted in ScienceDirect, Proquest,

Emerald Insight dan JSTOR. Keywords used in the

searching were (food OR agricultur* OR fish*) AND

(import OR export) AND (reject* OR refus* OR

9

Identification

Identification through database searching:

PROQUEST:4037articles;SCIENCEDIRECT:

2448articles;JSTOR:97articles;EMERALD

INSIGHT:628articles

(n =7210articles)

Selection through other

sources

Organization report:17articles

(n =17articles)

Afterduplicates

removed

(n =6996articles)

Screening

Literature excluded

(n =231articles)

Literature screened

(n =45articles)

Literature excluded

(n =6951articles)

Eligibility

Literature assessed for

eligibility

(n =18articles)

Included

Literature included in

analysis

(n =18articles)

Literature excluded (n =27articles):

• Full‐text unavailable (1articles)

• Notrelated to safety of Indonesian

food (5articles)

• Quantitative notification notfound

(17articles)

• Contain notification dataprior to

2009(4articles)

2nd SIS 2019 - SEAFAST International Seminar

152

notif*) AND Indonesia for Proquest, Emerald Insight

and JSTOR whereas (food OR agriculture OR

fisheries) AND (export OR import) AND (reject OR

refusal OR notification) AND Indonesia were

keywords for ScienceDirect.

The literature selection processes included

duplication checking, screening for abstract and titles,

as well as assessing for eligibility of full-text (Figure

1). Several criteria were applied in the searching.

Inclusion criteria for selection in screening process

included peer-reviewed articles, titles and abstracts

related to food exportation and food safety issue,

articles are in English or Bahasa Indonesia. While,

inclusion criteria for assessing eligibility of a study

included the availability of full-text, the availability

of quantitative data on food notification, and the data

were issued during 2009 – 2019. Besides scientific

literature, searching was carried out for reports

related to food safety notifications in Search Engine.

The criteria for reports were related to food

exportation and food safety issue, articles are in

English or Bahasa Indonesia, the availability of

quantitative data on food notification, and the data

were issued during 2009 – 2019

2.2 Data Extraction and Grouping

Number of notifications were identified from selected

literature. The notifications were grouped under

several classifications, based on food and hazard

associated with the notification. Food was grouped

into four major categories, including fishery based

fresh food, plant or animal based fresh food,

minimally processed foods and processed foods. Each

major group was divided into several sub-groups,

which is called commodities (Table 1). While,

hazards associated with notification were also divided

into several major groups. These major groups were

chemical hazards, microbiological hazards, and non-

chemical and microbiological hazards (Table 2).

2.3 Information Presentation

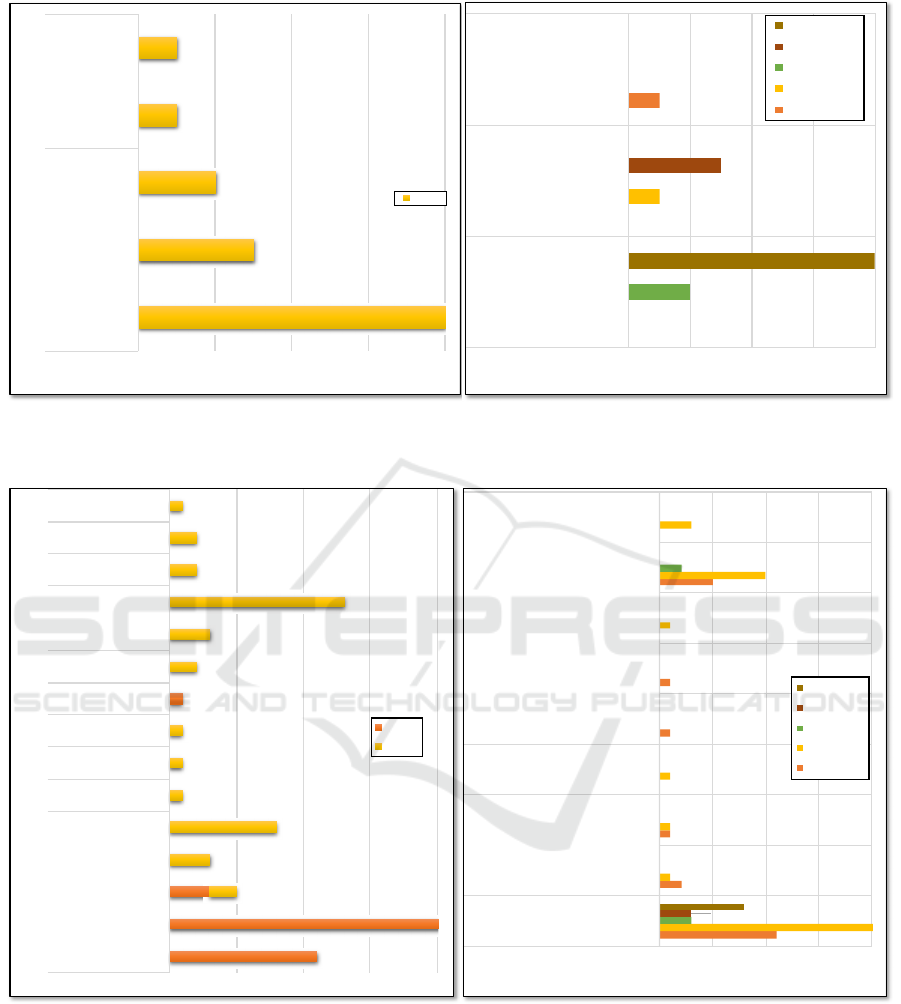

Notification data were presented in a form of bar

charts. The charts consist of notification numbers and

references (expressed as first author and year of

publication). Notification type was divided into two

categories, which was due to refusals and due to other

reasons. Refusals were mostly reported as the cause

of notification whereas alert, information, and news

were less reported by references. There were two

types of bar charts presented in each major food

group. First chart reported notification number based

on commodities and related references. While another

chart presented the number of notifications based on

hazard types and related references.

Table 1: The classification of notified foods.

Group Commodities Examples as Reported

in References

Fishery

Based

Fresh

Food

Fish Fish, frozen catfish,

red tail gobi, todak,

tuna, frozen tuna

steak, trout

Crustacea Crab, Shrimp

Chephalophod Frozen squid, frozen

octopus, chepalophod

Plant or

Animal

Based

Fresh

Food

Stimulants Coffee

Herbs and

Spices

Cooked spices,

nutmegs, cinnamon

Frog legs Frozen frog legs

Rice Rice

Minimally

Processed

Foods

Dessicated

coconut

Dessicated coconut

Processed

Foods

Instant noodle Instant noodle

Canned Food Canned Food

Sauces Chilli sauce

Chips and

Snacks

Chips, ceriping pedas,

potato chips, cassava

chips, shrimp chips,

fruit chips

Processed

peanut

Medan peanut

Biscuit/Wafer Biscuit, chocolate

wafer

Chocholate

product

Chocolate, chocolate

bar

Beverages Ginger beverages

Food

contact

materials

Gloves Gloves

3 RESULTS

3.1 Literature Included in Systematic

Review

3.1.1 Research Papers

The search strategy resulted in as many as 7,210

articles from scientific databases (Proquest,

ScienceDirect, JSTOR dan Emerald Science) (Figure

1). As many as 231 articles were exluded due to

duplication. Selection process reduced the number of

articles, from 6,951 into 28 articlesOne article was

not available for full-text (Moazami and Jinap, 2009).

Publications from Kok and Radzi (2017), FitzSimons

Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export

153

Table 2: The classification of hazard causing notification.

Hazard

group

Hazard types Examples as Reported

in References

Chemical Allergen Allergen

Hazardous

Substances

Leucocrystal violet,

Leucomalachite green,

Unsafe add

Food

Additives

Cyclamate, sulphite,

azorubine

Heavy metals Cadmium, mercury,

heavy metals

Total

migration

Packaging material total

migration

Mycotoxin Aflatoxin, ochratoxin

Processing

contaminants

Benzopyrene, PAH

Pesticide

residues

Carbaryl

Histamine Histamine

Chlorampheni

col

and

Veterinary

Drug

Residues

Chloramphenicol,

nitrofurans, veterinary

drugs

Microbio-

logical

Pathogenic

Bacteria

Bacillus, Salmonella,

Streptococcus faecali,

Vibrio

Fungi/Yeast Fungi

Bugs

infestation

Bugs

Non-

chemical

and

microbio-

logical

Filth Filth

Improper

process

Lacks Firm,

Inappropriate

temperature control,

Unregistered Low Acid

Canned Food Company

Improper

labelling

Undeclared coloring

and sulphite and GMO

Improper

Certification

Improper Health

Certificate, No Health

Certificate

Poisonous Poisonous

(2010), Wan Norhana et al. (2010), Majumder and

Banik (2019), and Quested et al. (2010) were

focusing on aspects which are irrelevant to the safety

of Indonesian food products. As many as 14

references have already mentioned the safety of

Indonesian food products, however no information

about the quantity of notification were found

(Anggrahini et al., 2015; Bachev and Ito, 2013; Bhat

and Reddy, 2017; Hassan et al., 2018; Imperato et al.,

2011; Kleter et al., 2009; Manning, 2016; Marroquín-

Cardona et al., 2014; McLauchlin et al., 2019;

Paterson et al., 2014; Reiter et al., 2010; Robertson et

al., 2014; Skretteberg et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2013).

While, four scientific publications have reported

notification number on Indonesian exported food

products, however the notification were received

before 2009 (Banach et al., 2016; Bouzembrak et al.,

2018; Jongwanich, 2009; Kuchler et al., 2010).

Therefore, the assessment of eligibility resulted in

four articles for further analysis (Table 3).

Four articles analyzed information from refusal

database published by institutions who have

authorities to notify high-risk imported foods.

Wahidin and Purnhagen (2018) as well as D.’Amico

et al. (2018) studied the information from the

database published in EU-RASFF website. Dataset of

food refusal by US-FDA was used as materials for

analysis by Fahmi et al. (2015). While, Nugroho

(2014) studied imported food rejection by Japanese

food authority.

3.1.2 Other Sources

There were 17 articles obtained in search by search

engine in internet. Sixteen of these sources were

annual reports from EU-RASFF and The National

Agency of Drug and Food Control, The Republic of

Indonesia (NADFC). EU-RASFF is an institution

who has the authority of notifying imported food

which do not meet the food safety requirements in

Europe, according to EC Regulation No 178/2002

related to General Principle of Food Law (EURASFF,

2018). The foundation of EU-RASFF is stated in the

article number 50 of The Law. The purpose of the

founding is to build information sharing system

among EU member countries to take actions

accordingly wherever imported high-risk imported

food are found (EURASFF, 2018).

EU-RASFF publishes annual report which

contain information on the number of notifications

from EU-member countries. The structures of annual

reports begin with the organization legal aspects and

then notification types. Then, there are parts which

discuss the most often hazards causing the

notifications (EURASFF, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015,

2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010). One of the important

parts of the report is the data on the number

notification, which is presented based on notifying

countries as well as country of origin for the imported

food. There are nine EU-RASFF annual reports as the

source of information in this study.

2nd SIS 2019 - SEAFAST International Seminar

154

Table 3: Main characteristics of selected scientific literature.

References Nugroho

(2015)

Fahmi et al. (2018) D.’Amico et al.

(2018)

Wahidin and Purnhagen

(2018)

Title The Impact of Food

Safety Standard on

Indonesia's Coffee

Exports

USFDA Import

Refusal and Export

Competitiveness of

Indonesian Crab in

US Market

Seafood products

notifications in the EU

Rapid Alert System

for Food and Feed

(RASFF) database:

Data analysis during

the period 2011–2015

Improving the level of

food safety and market

access in developing

countries

Objectives Presenting how a

regulation may affect

the global trade of

coffee from

Indonesia. Analysis

was performed using

Gravity Model

Analyze impor

refusal by US-FDA

on Indonesia crab

competitiveness in

The US market

To determine the

profile of notification

for seafood product

carried out by EU-

RASFF in 2011 –

2015

To investigate the risk

management of two case

studies: shrimp and

nutmeg, to formulate

policies to comply with

EU regulation as well as

to make Indonesian food

commodity competitive

Source of

notification

data

Secondary Secondary Secondary Secondary

Notifying

Country or

Institutions

Japan US-FDA EU-RASFF EU-RASFF

Notification

time

2008-2012

(notification data are

available per year)

2002-2013

(notification data are

available per year)

2011-2015

(accumulative)

2000-2017 (notification

data are available per

year)

Food type Coffee Crab Seafood Shrimp and Nutmeg

Hazard Type Several hazards, as

case studies

All related hazards All related hazards Several hazards, as case

studies

Conclusions Regulation on

ochratoxin affect

Indonesian coffee

commodities

compared to specific

country regulation,

for example carbaryl.

Furthermore, bilateral

negotiation may settle

issues related to

specific country

regulation.

Indonesia

experienced numbers

of crab refusal in

2002 – 2013, with

381 cases.

Chloramphenicol was

the most reason for

refusals, with 171

cases.

The highly

competitive

commodities were

unfrozen and

processed crab

whereas frozen crabs

were considered

fairly competitive.

RASFF database

provides useful

information to know

the recent food safety

issues.

Analyisis results

indicates that attention

should be paid not

only to imported

product but also

produced in EU

Furthermore, the

information is useful

for hazard

identification

FSO/ALOP analysis

showed that “top-down”

approach is more suitable

to settle chloramphenicol

in shrimp issue. Whereas

“bottom-up” approach is

necessary to overcome

the issue of aflatoxin in

nutmeg

Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export

155

(a) (b)

(c)

Figure 2: Notifications of exported food from Indonesia 2009 – 2019 as reported in annual reports (a) and scientific literature

(b) as well as their hazards of concern (c).

150

281

240

11

16

26

20

63

35

40

17

32

29

38

21

47

26

23

0 100 200 300 400

EURASFF,2010

EURASFF,2011

EURASFF,2012

BPOM,2013

EURASFF,2013

BPOM,2014

EURASFF,2014

BPOM,2015

EURASFF,2015

BPOM,2016

EURASFF,2016

BPOM,2017

EURASFF,2017

EURASFF,2018

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Number of notifications

Year of notification /References

Refusal

Others

66

1

2

30

5

2

23

3

2

186

1

2

25

4

10

7

20

4

2

4

5

2

1

1

1

1

23

0 50 100 150 200

Fahmi, 2015

Wahidi n,2018

Nu groho ,2014

Fahmi, 2015

Wahidi n,2018

Nu groho ,2014

Fahmi, 2015

Wahidi n,2018

Nu groho ,2014

Fahmi, 2015

Wahidi n,2018

Nu groho ,2014

Fahmi, 2015

Wahidi n,2018

Wahidi n,2018

Wahidi n,2018

Wahidi n,2018

Wahidi n,2018

D.'Amico,2018

2009 20 10 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

2011

‐

2015

Number of notifications

Year of notification /References

Refusal

Others

72

8

72

1

51

5

2

199

23 25

12

13

8

29

17

18

14

2

1

20

26

16

15

8

239

3

13

2

1

3

1

1

1

12

5

6

282

2

1

3

2

11

5

10

3

180

2

37

3

59

4

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

Un kno wn

Poisonous

Labelling

Inapproriatecertifi cation

Inappropr iatep rocessing

Filt h

Pathogenbact eria

Insect infestati on

Fungal/yeastcont amination

Unathorized su bsta nc es

Tot almigration

Processingcontaminant

Pesticideresid ue

Mycotoxin

Histamine

Heavymetalcontamination

Excessivefoodadditi ves

Chloramfen ikolandVeterinary DrugResid ue

Alergen

Unkn

own

Nonchemicalsand

mic rob iolo g y Micr obio logy Chemicals

Numberofnotification

Hazards

BP OM ,2013

BP OM ,2014

BP OM ,2015

BP OM ,2016

BP OM ,2017

D.'Amico,2018

EUR A SFF, 2010

EUR A SFF, 2011

EUR A SFF, 2012

EUR A SFF, 2013

EUR A SFF, 2014

EUR A SFF, 2015

EUR A SFF, 2016

EUR A SFF, 2017

EUR A SFF, 2018

Fah mi,2015

Nu groho ,2014

Wahidin,2018

2nd SIS 2019 - SEAFAST International Seminar

156

NADFC is a government agency which serves as

the secretarat of Indonesia Rapid Alert System for

Food and Feed (INRASFF). INRASFF has a function

more or less the same as EU-RASFF, which facilitate

information exchange between contact points of

Indonesian ministries and agencies related to

following up notified exported food or high-risk

imported foods (BPOM, 2018). The numbers of

Indonesian exported food notification are mostly

found in NADFC annual reports (BPOM, 2017, 2016,

2015, 2014, 2013). However, two annual reports do

not provide the number of notifications of Indonesian

exported food (BPOM, 2018, 2012). Nevertheless,

five annual reports provide valuable information for

analysis in this study, despite of the variability of

notification presented.

An analysis report on refusal by The US

government also became the result of literature

searching process in web search engine. Unlike EU-

RASFF and NADFC, US-FDA does not provide the

number of refusals in their annual reports. However,

a study conducted by Bovay (2016) aimed at showing

trends of refusal of imported food by The US. Bovay

(2016) analyzed the data from OASIS and stated that

Indonesian seafood were among the most refused

food commodities by The US government.

Unfortunately, the number of refusals of these

commodities are not available in the report, as well as

the information of hazards causing the notifications.

Therefore, this report was excluded for analysis in

this study

3.2 Notified Foods During 2009 – 2019

The number of notifications and refusals reported in

NADFC annual reports is more than that of EU-

RASFF (Figure 2a). The number of notifications for

Indonesian exported food was around 16 – 27 in 2009

– 2019 as reported in EU-RASFF annual reports

(EURASFF, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013,

2012, 2011, 2010). Only one annual report published

the number of border rejections, as many as 11

rejections in 2016. NADFC collected Indonesian

exported food notifications from many sources,

including EU-RASFF, The US, Malaysia, and South

Korea (BPOM, 2017, 2016). Besides that, NADFC

also shows the refusals as reported in OASIS. The

number of notifications for Indonesian exported food

was around 63 and 40 in 2012 – 2013, respectively

(BPOM, 2014, 2013). Then, the number rose in the

range of 182 – 319 during 2014 – 2016 (BPOM, 2017,

2016, 2015). Starting 2014, NADFC included refusal

data from OASIS, which made the number of

notifications more than that as reported by EU-

RASFF.

Research papers commonly discuss the refusals of

specific food commodities. Therefore, the reported

numbers of notifications from scientific papers are

less than that from organization annual reports

(Figure 2b). The highest number of notified foods are

reported by Fahmi et al. (2015). Fahmi et al. (2015)

used crab refusal data from OASIS for analysis.

Notifications without knowing the hazards were

commonly found in selected references (Figure 2c).

Chemicals were the known hazards causing most

notification as reported in 11 references. The number

of notification due to this type of hazard were

between two and 200 notifications (BPOM, 2017,

2016, 2015, 2013; D.’Amico et al., 2018; EURASFF,

2017, 2016, 2013; Fahmi et al., 2015; Nugroho, 2014;

Wahidin and Purnhagen, 2018). Microbiological

hazards as the causes of notifications were reported

by five references. The numbers of notification

ranged between three until 14 notifications (BPOM,

2017, 2016, 2014; EURASFF, 2013; Fahmi et al.,

2015). In non-chemical and microbiological hazards

category, only three references reported the

notification, ranging from three until 125

notifications.

3.3 Fishery based Fresh Foods

Notification during 2009 – 2019

Food from fishery products received most

notification compare to other major food groups

(Figure 3a). Crustacea was the most notified food,

reaching 330 notifications during 2009 – 2019 as

reported by one reference (Fahmi et al., 2015).

However, there were two foods included in crustacea

group, where crabs were the most notified while

shrimp only received one notification (BPOM, 2017;

Fahmi et al., 2015). Unlike crustacea group,

chepalopod and fish commodities received less than

20 and 10 notifications, respectively, as reported by

four references (BPOM, 2017, 2016; D.’Amico et al.,

2018; EURASFF, 2013). However, there are more

notifications for sub groups which is unknown for the

details of commodities, ranging from 40 until 255

notifications (BPOM, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013).

This sub group was reported by most references in

this major groups, with five articles mentioned about

it (BPOM, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013).

Hazards causing notification in this major food

group mostly were chloramphenicol and veterinary

drug residue, poisonous, and filth eventhough each of

the hazard mentioned by one article (Figure 3b)

(Fahmi et al., 2015). However, pathogenic bacteria

Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export

157

(a) (b)

Figure 3: Notifications of exported fishery-based fresh foods 2009 – 2019 (a) and their hazards of concern (b).

(a) (b)

Figure 4: Notifications of exported plant and animal-based fresh foods 2009 – 2019 (a) and their hazards of concern (b).

were reported by more references, despite having less

notification with one until 14 notifications reported

(BPOM, 2017, 2016; EURASFF, 2013; Fahmi et al.,

2015). Other hazards, such as heavy metals,

histamine, unauthorized substances, inappropriate

processing, and labelling, reported by two references

each, with less than 10 notifications received (BPOM,

2017, 2016; D.’Amico et al., 2018; EURASFF, 2013;

Fahmi et al., 2015). The notifications without

knowing detail hazards were the most reported by

144

255

217

330

43

20

10

5

6

8

3

1

1

1

15

14

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350

BPOM,2013

BPOM,2014

BPOM,2015

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2017

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2017

D.'A mic o,2018

EURAS FF,2013

BPOM,2017

Fahmi ,2015

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2017

D.'A mic o,2018

EURAS FF,2013

Unknown Fish Crustacea Chephalopod

Number of notifications

Commodities/References

Refusal

Others

72

1

51

5

2

199

14

2

1

15

8

217

1

1

1

5

255

1

1

4

154

20

43

0 100 200 300

Un kno wn

Poisonous

Labellin g

Inappropriateprocessing

Filth

Pathogenbact eria

Un athorizedsubstance s

His tamine

Heavymetalcon taminat ion

Ch loramfen ikolandVeteri naryDrug

Resi due

Un kno

wn

No nchemicalsan d

microbiology

Microbi

ology Chemicals

Number of notifications

Hazards

BP OM,2013

BP OM,2014

BP OM,2015

BP OM,2016

BP OM,2017

D.'Amico,2018

EUR ASFF,2013

Fah mi,2015

3

5

11

8

11

55

4

14

18

13

18

8

1

17

1

1

0 20406080

BP OM,2013

BP OM,2014

BP OM,2015

BP OM,2016

BP OM,2017

Nu groho ,2 014

BP OM,2016

BP OM,2017

EUR A SF F, 2016

EUR A SF F, 2017

Wahidi n, 2018

BP OM,2016

BP OM,2017

Un kno wn

Stimul

ants Spicesan dHerbs Rice

Frog

foot

Number of notifications

Commodities/References

Refusal

Others

4

14

21

6

2

11

11

13

1

2

1

2

8

12

72

8

0 20406080

Un kno wn

Inapproria tecertification

Filt h

Pathogenbacteria

Insect infestation

Fungal/yeast cont a mination

Pesticideresid ue

Mycotoxin

Un kno wn

No nchemicalsan d

mic robiolo gy Microbio logy Chemicals

Number of notifications

Hazards

Nugroho,2014

Wahidin,20 18

EURASFF,2017

EURASFF,2016

BPOM,20 17

BPOM,20 16

BPOM,20 15

BPOM,20 14

BPOM,20 13

2nd SIS 2019 - SEAFAST International Seminar

158

most references in this major food group, ranging

from 15 to 255 notifications (BPOM, 2017, 2016,

2015, 2014, 2014; D.’Amico et al., 2018).

3.4 Plant or Animal based Fresh Food

Notification During 2009 – 2019

The number of notifications in this major food group

was not as high as that of food from fishery (Figure

4a). Herbs and spices dominated the number of

notified foods as reported in most references. These

commodities received 8 – 72 notifications during

2009 – 2019 as discussed in five references (BPOM,

2017, 2016; EURASFF, 2017, 2016; Wahidin and

Purnhagen, 2018). While other commodities, such as

frog legs, rice, and stimulants only discussed in one

reference each, with less than 10 notifications

(BPOM, 2017, 2016; Nugroho, 2014). The numbers

of notification without the detail of foods were also

reported in five references, ranging from four to 18

notifications (BPOM, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013).

Mycotoxin was the most reported hazards of

causing the notifications (Figure 4b). There were six

references discussed and quantified this hazard,

ranging from four to 72 notifications (BPOM, 2017,

2016, 2013; EURASFF, 2017, 2016; Wahidin and

Purnhagen, 2018). Other hazards, such as pesticide

residue, fungi/yeast contamination, insect infestation,

pathogenic bacteria, filth and inappropriate

certification, were reported by one reference each,

with less than 13 notifications (BPOM, 2017, 2016;

Nugroho, 2014). Notifications with no mentioned

hazards were reported in four references, ranging

from six to 21 notifications (BPOM, 2017, 2016,

2015, 2014).

3.5 Minimalized Processed Food

Notification During 2009 – 2019

Notifications received by this major food group were

the least reported notification compare to other major

food groups (Figure 5a). The only commodity

reported in this major food group was dessicated

coconut. There were two references reported this

commodity, receiving one notification each (BPOM,

2017, 2016). Hazards reported in this major food

group were pathogenic bacteria and excessive food

additive (Figure 5b). Pathogenic bacteria were

reported in one notification as reported by BPOM

(2016) and three notifications as reported by BPOM

(2014). While, excessive food additives were

reported as the cause of one notification by BPOM

(2017).

3.6 Processed Food and Food Contact

Material Notification During 2009 –

2019

This major food group was also included as less

notified food, both by refusal other other reasons

(Figure 6a). Chips and snacks were the only food

commodity receiving more notifications compare to

other commodities in this food group. The

notifications reported in BPOM (2016) and BPOM

(2017), with 13 and 3 notifications, respectively.

Other commodities, such as beverages,

biscuit/wafers, canned foods, chocolates, instant

noodles were reported having one notification, with

less than three notifications, and as reported by one

reference for each commodity (BPOM, 2017, 2016).

Beside food, food contact material also had one

notification as reported by one reference (BPOM,

2017).

There were more hazard types reported in

chemicals group compared to other hazard group in

this major food category (Figure 6b). Excessive food

additives was the most cause of notification, with

three references reported 2 – 10 notifications (BPOM,

2017, 2016, 2015). Other hazards, such as allergen,

heavy metal, processing contaminant, total migration

were reported causing one notification each except

for allergen with three notifications (BPOM, 2017,

2016). Inappropriate processing and labelling were

reported by two references each, for causing mostly

one notification (BPOM, 2017, 2016). While,

pathogenic bacteria were reported causing one

notification by one reference (BPOM, 2016).

However, there were many unidentified food

commodities receiving notification as well as

unidentified causing hazards, ranging from 3 – 21

notifications (BPOM, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013).

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 The Notification of Indonesian

Exported Food During 2009 – 2019

There seems a wide opportunity to explore the

notification of Indonesian exported food and publish

it in international scientific literature. Of 7,210

articles found, only eight papers contain information

on the quantity of Indonesian exported food

notification (Banach et al., 2016; Bouzembrak et al.,

2018; D.’Amico et al., 2018; Fahmi et al., 2015;

Jongwanich, 2009; Kuchler et al., 2010; Nugroho,

2014; Wahidin and Purnhagen, 2018). However, only

Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export

159

(a) (b)

Figure 5: Notifications of exported minimally processed foods 2009 – 2019 (a) and their hazards of concern (b).

(a) (b)

Figure 6: Notifications of exported processed foods 2009 – 2019 (a) and their hazards of concern (b).

four articles published the notification on 2009 –

2019, which can be included for analysis in this study

(D.’Amico et al., 2018; Fahmi et al., 2015; Nugroho,

2014; Wahidin and Purnhagen, 2018). Those four

articles analyzed refusal data from published dataset

by the authorities. The refusal data may be used for

several purposes, such as studying food refusal

trends, emerging hazards early detection, as well as

prevention of future risks (D.’Amico et al., 2018).

D.’Amico et al. (2018) studied refusal data from EU-

RASFF to determine the trend of refusal for imported

seafood to EU as well as to characterize hazards most

contributing to the refusals. D.’Amico et al. (2018)

also concluded that the refusals may be a valuable

8

3

2

1

1

02468

BPOM,2013

BPOM,2014

BPOM,2015

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2017

Unk n o wn De ssiccat ed Coco nut

Number of notifications

Commodities/References

Others

1

1

2

3

8

02468

Un kno wn

Pathogenbacteria

Excessivefoodadditives

Unkno wn Micr obio log y Ch emicals

Number of notifications)

Hazards

BPOM,2013

BPOM,2014

BPOM,2015

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2017

11

21

3

1

2

3

8

1

1

1

2

3

13

2

2

1

BPOM,2017

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2015

BPOM,2014

BPOM,2013

BPOM,2017

BPOM,2017

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2017

BPOM,2017

BPOM,2017

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2017

BPOM,2016

Unknown Sauce

Peanut

produc

ts

Instant

Noodle Gloves

Chocol

ate s Chips/Snacks

Canne

d

foods

Bis cuit

/Wa fer

Be vera

ges

Number of notifications

Co mmo dities /References

Refusal

Others

11

2

1

1

1

5

1

1

1

1

10

3

3

2

3

8

0 5 10 15 20

Unkno wn

Labelling

Inappropriateprocessing

Pathogenbacteria

Totalmigrat ion

Processing contaminant

Heavymetal contamination

Excessivefoodadd itives

Alergen

Un kno wn

No nchemicalsand

microbiolo gy

Microbiol

ogy Chemicals

Number of notifications

Hazards

BPOM,2013

BPOM,2014

BPOM,2015

BPOM,2016

BPOM,2017

2nd SIS 2019 - SEAFAST International Seminar

160

information for hazard identification in food safety

risk assessment step.

Another example of a study using EU-RASFF

database was a study conducted by Banach et al.

(2016). The purpose of the study was to determine the

trend of food safety hazards in herbs and spices

commodities during 2004 -2014. Banach et al. (2016)

combined EU-RASFF database with other literatures,

such as annual report of European Food Safety

Authority, World Health Organization Global

Environmental Monitoring System (GEMS)/Food

database, and The Netherland Food and Consumer

Product Safety Authority database. Banach et al.

(2016) showed that several herbs and spices, such as

blackpepper and dried herbs, were dominated by

pathogenic bacteria, such as Salmonella spp. and E.

coli whereas Bacillus spp. was also found in chillies

and curries. Mycotoxin contamination was a major

cause of notification for herbs and spices as shown in

EU-RASFF database, GEMS/Food database and The

Netherland Food and Consumer Product Safety

Authority database. The mycotoxin contamination

caused more than 500 notifications as recorded in

EU-RASFF database and The Netherland Database,

even reaching 30,000 notifications as recorded in

GEMS/Food database (Banach et al., 2016). Banach

et al. (2016) concluded that the most concerned

microbiological hazards for herbs and spices were

Salmonella spp and Bacillus spp whereas most

concerned chemical hazards were aflatoxin B1 and

ochratoxin A. Moreover, Banach et al. (2016) also

recommended the use of notification data collected in

authorized institutions database for hazard

identification as also suggested by D.’Amico et al.

(2018).

Fishery based fresh food is one of the important

export commodities for Indonesia. Besides for

exporting, the high number of fish resources, which

is estimated reaching 12.5 tonnes in 2016, makes this

commodity reliable for domestic consumption as well

(KKP, 2018). However, this food is the most

receiving notification compared to other major food

groups (Figure 3a). Rosabel (2018) conducted a study

related to the refusal of Indonesian exported food by

the US in 2010 – 2017 by using OASIS database. The

average of refusals of Indonesian product was 282

cases per year in 2010 – 2017, dominated by fishery

products with the average of 126 refusal cases per

year (Rosabel, 2018). The refusal number is almost

the same as the difference between notification of

Indonesian food as reported by EU-RASFF and

NADFC (Figure 2a). It suggests that refusal by The

US government dominated the number of

notifications of Indonesian exported foods. Rosabel

(2018) study was in line with study conducted by

Bovay (2016). Indonesia, together with Thailand, was

the most countries receiving notification from US-

FDA for fishery products (Bovay, 2016).

Further exploration is needed for determining the

most commodity receiving notification in food from

fishery group. In this study, the most notified food

from fishery was crabs as reported by Fahmi et al

(2015) (Figure 3a). However, there were numbers of

notifications, which were unable to determine the

details of the commodities as well as the causing

hazards, ranging from 40 until 255 notifications

(BPOM, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013). Therefore, it

is likely that there were other commodities which

received notifications at the same amount or even

more than crab commodities. Rosabel (2018) found

that tuna dominated in the number of refusals by US-

FDA, receiving more than 1,000 out of 2,019

notifications of seafood products. The number of

notifications of snapper, shrimp and crab were almost

the same, which were 245, 242 and 232 notifications,

respectively (Rosabel, 2018). On the other hand,

Irawati et al. (2019) reported that tuna was the most

notified food from The European Union on 2011 –

2017, with 27 notifications. Whereas in this study,

fish commodity was reported receiving only 3 – 8

notifications (BPOM, 2017, 2016; D.’Amico et al.,

2018; EURASFF, 2013). Further analysis of

notification using published database by authorized

institutions may be carried out to get better profile of

the notified fishery-based foods.

Chloramphenicol and veterinary drug residue,

poisonous and filth, and pathogenic bacteria

dominated as the cause of notification in fishery

based fresh food. Chloramphenicol is prohibited to be

added in animals as food ingredient in many

countries, because of possibility causing cancer and

aplastic anemia in humans (Berendsen et al., 2010).

Veterinary drugs commonly used to treat and to

prevent animal disease in aquaculture. However,

imprudent used of these drugs may contribute to

antimicrobial resistence of pathogenic

microorganism (Economou and Gousia, 2015). Food

authorities have urged prudent use of veterinary drugs

as a prevention step from antimicrobial resistence.

Food refusals due to chloramphenicols and veterinary

drug residues are also reported in elsewhere. Rosabel

(2018) reported that 202 refusal cases of crab producs

was due to these chemicals during 2010 – 2017.

Rahmawaty et al. (2014) also reported the number of

seafood refusal due to chloramphenicol, as many as

29 cases in 2010 – 2012. Food is considered

adulterated if there are poisonous ingredient,

prohibited colorants and filth, according to The US

Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export

161

Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Bovay, 2016). Filth

is defined as common sense, any materials supposed

not to be in the food, such as bugs, parasites, metal

shards, and glass pieces (USFDA, 2013).

Pathogenic bacteria were another hazard not

many reported as the cause of notifications. In this

study, four references reported notifications due to

these bacteria, ranging from only 1 – 14 notifications

in 2009 – 2019 (BPOM, 2017, 2016; EURASFF,

2013; Fahmi et al., 2015). On the other hands, several

studies reported numbers of notification were caused

by this hazard. Rosabel (2018) reported that the

number of refusals for food from fishery product due

pathogenic microorganisms may reach 706 cases in

2010 – 2017. Rahmawaty et al. (2014) also reported

534 refusal cases of foods from fishery-based food

due to the same hazards in 2010 – 2012. Both of them

mentioned that pathogenic microorganisms were

included as major cause of notification for this fishery

food. The different results may be from different

methodology used in this study. However, this study

also resulted in several notifications with unidentified

food commodities and hazards. Further study may be

needed to reveal those unidentified notifications.

Herbs and spices are the most notified

commodities in plant or animal based fresh food, as

reported in both annual reports and research papers

(Figure 4a). Enhancing flavor and bioactive

compounds are the purpose of addition of herbs and

spices in food (Banach et al., 2016). One of popular

foods in this commodity is nutmeg. Nutmeg is

commonly consumed as powder mixed in the food.

This study showed that mycotoxin dominated as the

cause of refusals. Several literature also report that

this food is contaminated with pathogens and

mycotoxins (Banach et al., 2016). Eventough nutmeg

consumption level is low in Indonesia, the presence

of mycotoxin makes this food included as high-risk

food (Wahidin and Purnhagen, 2018).

Several attempts have been made by Indonesian

authorities to minimize contamination of mycotoxin,

starting from improving handling practices until

providing education for exporters (Kemtan, 2018).

Importing countries also implement policy to control

incoming nutmegs, for example EU issued

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/24

of 8 January 2016 on imposing special conditions

governing the import of groundnuts from Brazil,

Capsicum annuum from India and nutmeg from

Indonesia and amending Regulations (EC) No.

669/2009 and (EU) No 884/2014. This regulation

requires health certificate on importing nutmegs from

Indonesia and checking for 20% of every

consignment as sample (EU, 2016). Implementation

of good practices in exporting countries and

continuous education for exporters are necessary to

minimize the chance of being notified by importing

countries.

Dessicated coconut is one of the examples of

minimally processed foods with highly competitive

value for global trade. This commodity is considered

as high potency of export, beside other coconut

product, such as nata de coco, brown sugar, and

coconut shell (Probowati et al., 2011). Dessicated

coconut has not only high nutrition value but also

many usages. Fat and oil, carbohydrate and protein

content from this commodity around 60%, 20% and

7% of total weight, respectively (DebMandal and

Mandal, 2011). Therefore, dessicated coconut can be

suitable ingredients for biscuits (Manley, 2000).

However, notifications are also received for this

commodity eventhough the numbers is less (Figure

5a). Salmonella spp., Streptococcus spp., and

Bacillus spp. caused four notifications in 2013 and

2015 (BPOM, 2016, 2014). Whereas, food additives

cause one notification of this food in 2016 (BPOM,

2017). The presence of pathogenic bacteria may be

from contaminated water used for cleaning coconut

prior to drying process whereas shulphur dioxide may

be from fuel impurities (Manley, 2000). National

authorities should pay attention to this commodity

since Indonesia is one of the world suppliers of this

product, together with Sri Lanka and Philipine

(Manley, 2000).

One of the most reasons for notified processed

food is the use of food additives. Chips and snacks are

the commodities mostly notified in 2015 and 2016,

with 13 and 3 notifications, respectively (Figure 6a).

However, the notifications due to difference in food

safety regulation between Indonesia and importing

countries. There are additives, for example cyclamate

and sulphite, which are not permitted to be used in

food in importing countries eventhough those food

additives are permitted with maximum limits in

Indonesia (BPOM, 2017, 2016). Continous education

to food producers and exporters on food safety

regulation in importing countries is required for

reducing the numbers of notification.

4.2 Recommendation for Risk Profiling

Several major notifications in Indonesian food export

may be used as a starting point for the development

of risk profiles. In fishery based fresh food products,

this study results suggest that risk profile may be

developed for crab, because of the number of

notifications. This commodity was reported to

contain chloramphenicol, veterinary drug residues,

2nd SIS 2019 - SEAFAST International Seminar

162

poisonous and filth. However, other hazards may be

present in this food. There is also possibility that other

fishery products needed to be further explored for risk

profiling. Fish, together with cephalopod, are

commodities discussed by more references. Several

other studies also reported fish commodity mostly

received notifications (Rahmawaty et al., 2014;

Rosabel, 2018).

Herbs and spices, including nutmeg, is one of

main topics of notification in plant or animal based

fresh food. Several efforts have been made however

there are re-occured notifications. Profiling of risk

factors in producing chains may be necessary for

mitigating strategies. Eventhough having less

notifications, dessicated coconut may also be

prioritized for profiling. It is due to Indonesia is major

supply for this food for the world (Manley, 2000).

5 CONCLUSION

Fishery based fresh food was the most receiving food

safety notification during 2009 – 2019. Crustacea,

especially crab, was the most notified, whereas fish

and cephalopod were discussed in more references.

The type of hazards most discussed in this food group

were chloramphenicol and veterinary drug residue,

filth, poisonous and pathogenic bacteria. Herbs and

spices dominated in terms of notification in plant or

animal based fresh food, with mycotoxin were the

most reported hazards of concern. The number of

notifications of minimally processed and processed

food were lower than that of fresh food.

Comprehensive risk profiles may be developed for

fishery and plant or animal-based food. The profile

may identify risk factors contributing to food safety

notification as well as gaps for research needed. The

profile may also be developed for minimally

processed and processed food due to their

contribution to Indonesian revenue. This study is

limited to the figures reported in published literatures

from selected scientific database. Expanding the

scope of database and analyzing data directly from

the dataset published by notifying authorities may be

useful for determining unidentified foods and hazards

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Puspo Edi Giriwono, PhD. for assisting in a

systematic review methodology as well as reviewing

and proof-reading this article.

REFERENCES

Anggrahini, D., Karningsih, P.D., Sulistiyono, M., 2015.

Managing Quality Risk in a Frozen Shrimp Supply

Chain: A Case Study. Procedia Manufacturing 4, 252–

260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2015.11.039

Bachev, H., Ito, F., 2013. Impacts of Fukushima Nuclear

Disaster on Agri-Food Chains in Japan. IUP Journal of

Supply Chain Management 10, 7–52.

Banach, J.L., Stratakou, I., van der Fels-Klerx, H.J., Besten,

H.M.W. den, Zwietering, M.H., 2016. European

alerting and monitoring data as inputs for the risk

assessment of microbiological and chemical hazards in

spices and herbs. Food Control 69, 237–249.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.04.010

Berendsen, B., Stolker, L., de Jong, J., Nielen, M.,

Tserendorj, E., Sodnomdarjaa, R., Cannavan, A.,

Elliott, C., 2010. Evidence of natural occurrence of the

banned antibiotic chloramphenicol in herbs and grass.

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 397, 1955–

1963. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-010-3724-6

Bhat, R., Reddy, K.R.N., 2017. Challenges and issues

concerning mycotoxins contamination in oil seeds and

their edible oils: Updates from last decade. Food

Chemistry 215, 425–437.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.161

Bouzembrak, Y., Camenzuli, L., Janssen, E., van der Fels-

Klerx, H.J., 2018. Application of Bayesian Networks in

the development of herbs and spices sampling

monitoring system. Food Control 83, 38–44.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.04.019

Bovay, J., 2016. FDA Refusals of Imported Food Products

by Country and Category.

BPOM, 2018. Laptah 2017 Laporan Tahunan Badan

Pengawas Obat dan Makanan. Jakarta.

BPOM, 2017. Laptah 2016 Laporan Tahunan Badan

Pengawas Obat dan Makanan. Jakarta.

BPOM, 2016. Laptah 2015 Laporan Tahunan Badan

Pengawas Obat dan Makanan. Jakarta.

BPOM, 2015. Laptah 2014 Laporan Tahunan Badan

Pengawas Obat dan Makanan. Jakarta.

BPOM, 2014. Laptah 2013 Laporan Tahunan Badan

Pengawas Obat dan Makanan. Jakarta.

BPOM, 2013. Laptah 2012 Laporan Tahunan Badan

Pengawas Obat dan Makanan. Jakarta.

BPOM, 2012. Laptah 2011 Laporan Tahunan Badan

Pengawas Obat dan Makanan. Jakarta.

Cressey, P., 2014. Risk Profile: Mycotoxin in Foods 2014.

Institute of Environmental Science & Research

Limited, Christchurch.

D.’Amico, P., Nucera, D., Guardone, L., Mariotti, M.,

Nuvoloni, R., Armani, A., 2018. Seafood products

notifications in the EU Rapid Alert System for Food

and Feed (RASFF) database: Data analysis during the

period 2011–2015. Food Control 93, 241–250.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.06.018

DebMandal, M., Mandal, S., 2011. Coconut (Cocos

nucifera L.: Arecaceae): In health promotion and

disease prevention. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical

Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export

163

Medicine 4, 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1995-

7645(11)60078-3

Economou, vangelis, Gousia, P., 2015. Agriculture and

food animals as a source of antimicrobial-resistant

bacteria. Infection and Drug Resistance 2015, 49–61.

https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S55778

EU, 2016. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU)

2016/24 of 8 January 2016 imposing special conditions

governing the import of groundnuts from Brazil,

Capsicum annuum and nutmeg from India and nutmeg

from Indonesia and amending Regulations (EC) No

669/2009 and (EU) No 884/2014.

EURASFF, 2018. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2017. Brussels.

EURASFF, 2017. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2016. Brussels.

EURASFF, 2016. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2015. Brussels.

EURASFF, 2015. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2014. Brussels.

EURASFF, 2014. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2013. Brussels.

EURASFF, 2013. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2012. Brussels.

EURASFF, 2012. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2011. Brussels.

EURASFF, 2011. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2010. Brussels.

EURASFF, 2010. The Rapid Alert System for Food and

Feed (RASFF) Annual Report 2009. Brussels.

Fahmi, A.S., Maksum, M., Suwondo, E., 2015. USFDA

Import Refusal and Export Competitiveness of

Indonesian Crab in US Market. Agriculture and

Agricultural Science Procedia 3, 226–230.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaspro.2015.01.044

FAO/WHO, 2007. Working Principles for Risk Analysis for

Food Safety for Application by Governments. Rome.

FitzSimons, D., 2010. Hepatitis A and E: Update on

prevention and epidemiology. Vaccine 28, 583–588.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.136

GMA, 2011. Capturing Recall Costs: Measuring and

Recovering the Losses. The Association of Food,

Beverage and Consumer Products Companies.

Hassan, R., Tecle, S., Adcock, B., Kellis, M., Weiss, J.,

Saupe, A., Sorenson, A., Klos, R., Blankenship, J.,

Blessington, T., Whitlock, L., Carleton, H.A.,

Concepción-Acevedo, J., Tolar, B., Wise, M., Neil,

K.P., 2018. Multistate outbreak of Salmonella

Paratyphi B variant L(+) tartrate(+) and Salmonella

Weltevreden infections linked to imported frozen raw

tuna: USA, March–July 2015. Epidemiology and

Infection 146, 1461–1467.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268818001462

Imperato, R., Campone, L., Piccinelli, A.L., Veneziano, A.,

Rastrelli, L., 2011. Survey of aflatoxins and ochratoxin

a contamination in food products imported in Italy.

Food Control 22, 1905–1910.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.05.002

Irawati, H., Kusnandar, F., D Kusumaningrum, H., 2019.

Analisis Penyebab Penolakan Produk Perikanan

Indonesia oleh Uni Eropa Periode 2007 - 2017 dengan

Pendekatan Root Cause Analysis. Jurnal

Standardisasi. 21, 149.

https://doi.org/10.31153/js.v21i2.757

Jongwanich, J., 2009. The impact of food safety standards

on processed food exports from developing countries.

Food Policy 34, 447–457.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2009.05.004

Kemtan, 2018. Penanganan Keamanan dan Mutu Pangan

Segar di Kementerian Pertanian, in: Prosiding WNPG

XI Bidang 3 Peningkatan Penjaminan Keamanan Dan

Mutu Pangan Untuk Pencegahan Stunting Dan

Peningkatan Mutu SDM Bangsa Dalam Rangka

Mencapai Tujuan Pembangunan Berkelanjutan.

Presented at the Widyakarya Nasional Pangan dan Gizi

XI, Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan, Jakarta.

KKP, 2018. Peningkatan Penjaminan Keamanan dan Mutu

Ikan dan Produk Perikanan, in: Prosiding WNPG XI

Bidang 3 Peningkatan Penjaminan Keamanan Dan

Mutu Pangan Untuk Pencegahan Stunting Dan

Peningkatan Mutu SDM Bangsa Dalam Rangka

Mencapai Tujuan Pembangunan Berkelanjutan.

Presented at the Widyakarya Nasional Pangan dan Gizi

XI, Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan, Jakarta.

Kleter, G.A., Groot, M.J., Poelman, M., Kok, E.J., Marvin,

H.J.P., 2009. Timely awareness and prevention of

emerging chemical and biochemical risks in foods:

Proposal for a strategy based on experience with recent

cases. Food and Chemical Toxicology 47, 992–1008.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2008.08.021

Kok, S.C., Radzi, C.W.J.M., 2017. Accuracy of nutrition

labels of pre-packaged foods in Malaysia. British Food

Journal 119, 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-07-

2016-0306

Kuchler, F., Krissoff, B., Harvey, D., 2010. Do Consumers

Respond to Country-of-Origin Labelling?: Journal of

Consumer Policy. Journal of Consumer Policy 33,

323–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-010-9137-2

Majumder, S., Banik, P., 2019. Geographical variation of

arsenic distribution in paddy soil, rice and rice-based

products: A meta-analytic approach and implications to

human health. Journal of Environmental Management

233, 184–199.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.12.034

Manley, D., 2000. Dried fruits and nuts, in: Technology of

Biscuits, Crackers and Cookies. Elsevier, pp. 169–176.

https://doi.org/10.1533/9781855736597.2.169

Manning, L., 2016. Food fraud: policy and food chain.

Current Opinion in Food Science 10, 16–21.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2016.07.001

Marroquín-Cardona, A.G., Johnson, N.M., Phillips, T.D.,

Hayes, A.W., 2014. Mycotoxins in a changing global

environment – A review. Food and Chemical

Toxicology 69, 220–230.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2014.04.025

McLauchlin, J., Aird, H., Andrews, N., Chattaway, M., de

Pinna, E., Elviss, N., Jørgensen, F., Larkin, L., Willis,

C., 2019. Public health risks associated with Salmonella

contamination of imported edible betel leaves: Analysis

of results from England, 2011–2017. International

2nd SIS 2019 - SEAFAST International Seminar

164

Journal of Food Microbiology 298, 1–10.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.03.004

Moazami, E.F., Jinap, S., 2009. Natural occurrence of

deoxynivalenol (DON) in wheat based noodles

consumed in Malaysia. Microchemical Journal 93, 25–

28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2009.04.003

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G., The

PRISMA Group, 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA

Statement. PLoS Medicine 6, e1000097.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Nugroho, A., 2014. The Impact of Food Safety Standard on

Indonesia’s Coffee Exports. Procedia Environmental

Sciences 20, 425–433.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.054

Paterson, R.R.M., Lima, N., Taniwaki, M.H., 2014. Coffee,

mycotoxins and climate change. Food Research

International 61, 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2014.03.037

Probowati, B.D., Arkeman, Y., Mangunwidjaja, D., 2011.

Penentuan Produk Prospektif untuk Pengembangan

Agroindustri Kelapa secara Terintegrasi, in: Prosiding

Seminar Nasional 2013. Presented at the Seminar

Nasional Menggagas Kebangkitan Komoditas

Unggulan Lokal Pertanian dan Kelautan, Universitas

Trunojoyo, Bangkalan.

Quested, T.E., Cook, P.E., Gorris, L.G.M., Cole, M.B.,

2010. Trends in technology, trade and consumption

likely to impact on microbial food safety. International

Journal of Food Microbiology 139, S29–S42.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.01.043

Rahmawaty, L., Rahayu, W.P., Kusumaningrum, H.D.,

2014. Pengembangan strategi keamanan produk

perikanan untuk ekspor ke Amerika Serikat. Jurnal

Standardisasi 16, 95–102.

Reiter, E.V., Vouk, F., Böhm, J., Razzazi-Fazeli, E., 2010.

Aflatoxins in rice – A limited survey of products

marketed in Austria. Food Control 21, 988–991.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2009.12.014

Robertson, L.J., Sprong, H., Ortega, Y.R., van der Giessen,

J.W.B., Fayer, R., 2014. Impacts of globalisation on

foodborne parasites. Trends in Parasitology 30, 37–52.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2013.09.005

Rosabel, C., 2018. Analisis Kasus Penolakan Pangan

Ekspor Indonesia oleh Amerika Serikat selama tahun

2010 - 2017. Bogor: IPB University

Skretteberg, L.G., Lyrån, B., Holen, B., Jansson, A.,

Fohgelberg, P., Siivinen, K., Andersen, J.H., Jensen,

B.H., 2015. Pesticide residues in food of plant origin

from Southeast Asia – A Nordic project. Food Control

51, 225–235.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.11.008

USFDA, 2019a. Import Alerts [WWW Document]. URL

https://www.fda.gov/industry/actions-

enforcement/import-alerts (accessed 8.6.19).

USFDA, 2019b. Additional Information about Recalls

[WWW Document]. URL

https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-

withdrawals-safety-alerts/additional-information-

about-recalls (accessed 8.6.19).

USFDA, 2013. ORA Laboratory Manual: Microanalytical

and Filth Analysis. Section 4 [WWW Document]. URL

https://www.fda.gov/files/science%20&%20research/p

ublished/Section-4-Microanalytical-and-Filth-

Analysis.pdf (accessed 8.16.19).

Wahidin, D., Purnhagen, K., 2018. Improving the level of

food safety and market access in developing countries.

Heliyon 4, e00683–e00683.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00683

Wan Norhana, M.N., Poole, S.E., Deeth, H.C., Dykes,

G.A., 2010. Prevalence, persistence and control of

Salmonella and Listeria in shrimp and shrimp products:

A review. Food Control 21, 343–361.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2009.06.020

Wang, H.H., Zhang, X., Ortega, D.L., Olynk Widmar, N.J.,

2013. Information on food safety, consumer preference

and behavior: The case of seafood in the US. Food

Control 33, 293–300.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.02.033

Food Safety Notification on Indonesian Food Export

165