Misfit-score Evaluation on Business and Manufacturing Strategies

and the Impact on Operational Performance

Titik Kusmantini

1

, Tulus Haryono

2

, Wisnu Untoro

2

, and Ahmad Ikhwan Setiawan

2

1

Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Yogyakarta

2

Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia

Keywords: Organizational Fit Theory; Business Strategy; Manufacturing Strategy; Misfit Score; Euclidean Distance;

Strategy Configuration

Abstract: This study aims to examine whether the higher degree of fit between business strategy and manufacturing

strategy will create a higher operational performance. The degree of fit in strategic alignment research using

misfit score because the basic assumption of configurational perspective is fit as a profile deviation and the

misfit score calculated with the Euclidean distance formula. The configuration of ideal strategy types is

grouped into two: business strategy type “Prospector” assumed to be aligned with manufacturing strategy type

“differentiator” (code 1) and business strategy type “defender” that is more aligned with manufacturing

strategy type “Innovator-efficient” (code 2). Hypothesis testing used 99 furniture companies in Indonesia and

using simple regression. Regression test results in Group 1 produced negative coefficient values, and the p-

value is significant, which means that the hypothesis is supported, while Group 2 have a positive coefficient

value. However, p value is not significant, which means that the hypothesis is not supported.

1 INTRODUCTION

Small and medium-sized companies (SMEs) in

Indonesia over the past decade have experienced

significant development both in terms of the number

of business units, the ability to provide employment,

or the level of productivity (Rahmawati & Nurlela,

2008). However, despite this growth, SME business

failures are still common occurrences. Research by

Kusmantini, et al. (2014) identified that the factor

triggering the failure of furniture SMEs in

Yogyakarta Special Province (Daerah Istimewa

Yogyakarta/DIY) in exports was the supplier's

inability to fulfill the requirements of export

documents such as Timber Legality Verification

Certification (Sistem Verifikasi Legalitas

Kayu/SVLK). Internal and external factors influence

the success and failure of SMEs.

This research focuses on the internal aspects of the

enterprises, especially aspects related to the decision

making the process about the strategy, both business

and manufacturing strategies, as recently there have

been developments in research topics that use strategy

implementation at the functional and business unit

levels as a basis. Skinner (1978) asserts that

manufacturing strategy is different from the business

strategy because it is only one of the functional

components, which in its implementation requires a

fit with business strategy and marketing strategy.

Therefore, the manufacturing strategy is called a

functional sub-strategy.

In the 1960s, manufacturing contribution to

overall corporate performance was less significant

(Skinner, 1969), because the top management as the

decision-maker had not yet understood the existence

of a strategic relationship between manufacturing and

business strategies (Swink et al., 2005; Ward et al.,

2007; Shavarini et al., 2012). Thus, a set of decisions

and activities in the factory (manufacturing) cannot

support competitive strategy decisions at the

corporate level. Mintszberg (1978) also emphasized

the importance of alignment between business and

manufacturing strategies because business strategy is

a way for companies to determine the company's

competitive position while the manufacturing

strategy is a way to achieve and maintain the

competitive position that the company wants. For this

reason, it is important for each company to determine

the sources of competitive advantage and determine

positional advantages (for example, superior

customer value or lower relative costs) that the

company wants to achieve because each positional

Kusmantini, T., Haryono, T., Untoro, W. and Setiawan, A.

Misfit-score Evaluation on Business and Manufacturing Strategies and the Impact on Operational Performance.

DOI: 10.5220/0009960101690178

In Proceedings of the International Conference of Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management (ICBEEM 2019), pages 169-178

ISBN: 978-989-758-471-8

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

169

advantage requires a fit between business strategies

and sources of functional organizational competence

(Baier et al., 2008), one of which is the field of

production.

With regard to competency excellence in

manufacturing (production), Oltra and Flor (2010)

and Ward et al (2007) emphasize the importance of

contingency approach. This is because the process of

developing manufacturing capabilities as the basis of

company competence is unique and specific in nature

which is contingent with the company's internal

resources or positional advantages that are targeted in

a competitive strategy (Venkantraman and Camillus,

1984). Companies that are oriented as market

pioneers and those oriented as imitators will need

different resources and capabilities in manufacturing.

The competitive strategy of a marketer-oriented

company will also consider different manufacturing

capabilities.

This research is based on Organizational Fit

Theory proposed by Galbraith and Nathonson (1978),

which state that strategies must be aligned with other

internal factors of the company to achieve better

performance. The concept of alignment referred to

here is in accordance with the definition of fit

proposed by Drazin and Van de Ven (1985), namely:

“fit is the internal consistency of multiple structural

characteristics: it affects performance

characteristics." This study specifically examines the

degree of alignment between manufacturing and

competitive strategies. In making decisions and

implementing the manufacturing strategy at the

functional level, it is important to have a fit in the

choice of the company's competitive strategy that

explicitly serves as the company's vision and mission

in determining the company's competitive position.

This study attempts to answer three main

questions: (1) whether there is a difference in the

choice of manufacturing competencies in furniture

companies in several furniture centers in Central Java

and DIY, (2) how much is the degree of alignment

between manufacturing and business strategies, (3)

how much is the influence of the degree of alignment

between manufacturing and business strategies on

factory operational performance.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Organizational Fit Theory (OFT)

Organizational Fit Theory was first introduced by

Galbraith and Nathanson (1978). The underlying

principle of this theory is that in order to create better

organizational performance, the alignment of

strategy, structure, and other contingency factors is

needed. Many typology approaches to strategy and fit

of strategy-structure refer to the concept of

contingency theory to improve performance. Some

opinions emphasize the importance of strategy-

structure management as one of the best ways for

companies to be able to adapt to the climate of their

respective industrial environments (Hage and Aiken,

1970; Lorsch and Morse, 1974). Some others argue

that organizational effectiveness is the result of the

accuracy of certain organizational characteristics to

be able to adjust to the situation or context within the

organization (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Hage and

Aiken, 1969; Pugh et al., 1969; Galbraith, 1973;

Priyono, 2004). Contingency factors include the

environment (Burns and Stalker, 1961), organization

size (Child, 1975), and functional strategies

(Chandler, 1962; Baier et al., 2008; Vachon et al.,

2009). This study argues that the alignment between

business strategies and functional strategies,

especially manufacturing strategies, can result in

better company performance.

2.2 Contingency Theory

This theory states that in an effort to achieve

effectiveness, organizations are required to make

decisions and policies that are in accordance with the

structure and internal factors of other organizations.

When the complexity of manufacturing practices is

contingent, the choice of certain manufacturing

capabilities as a basis for competency is more suitable

for a company and may be less suitable for other

companies. Therefore, in contingency theory,

organizational context becomes important.

Drazin and Van de Ven (1985) suggested three

types of contingency approaches. First, a selection

approach assumes that a fit as a consequence between

organizational contextual factors that becomes

fundamental without further testing whether the

alignment is influential or not. Second, interaction

approach characterizes a fit as the impact of

interaction between strategy and contextual variables

of the organization, and so the research focuses on

explaining the performance as a result of the

interaction between internal organizational variables

(as contingency variables) and the strategy. Finally,

system approach defines alignment as internal

consistency over several fit category alternatives with

several categorical structures that will affect

performance (Venkantraman, 1990; Doty et al.,

1993).

ICBEEM 2019 - International Conference on Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management

170

This study uses the system approach based on

several taxonomic research results. The

categorization of manufacturing strategies was

adopted from the research by Sum et al (2004) which

distinguishes the operating strategy group into 3 ideal

types, namely Differentiator, All Rounder, and

Efficient Innovator, which are assumed to be in line

with the ideal type of business strategy developed by

Miles and Snow (1978). However, the configuration

of strategy-fit uses two types of extreme strategies:

Prospectors that are more aligned with Differentiators

manufacturing strategy, and Defenders that are

aligned with the Efficient-Innovators manufacturing

strategy.

2.3 Manufacturing Strategy

Skinner (1969) defines manufacturing strategy as a

complex and dynamic decision-making process. This

strategy is complicated because decisions related to

assignments and activities in manufacturing must fit

and be aligned with those related to corporate and

other functions such as finance and marketing.

Besides, the strategy is also dynamic, which means

that it is able to adapt to changes in the circumstances.

Miller and Roth (1994) and Oltra and Flor (2010)

highlight two core elements of the manufacturing

strategy previously proposed by Skinner (1969).

These two core elements are the manufacturing task

and pattern of manufacturing choice. Manufacturing

task is defined as manufacturing capabilities that can

be used to achieve and maintain competitive positions

targeted by the company. Skinner (1990); Hayes and

Wheelwright (1984); Ferdows and De Meyer (1990);

Roth and Miller (1992); Ward and Duray (1998) and

Oltra and Flor (2010) suggest five critical capabilities

in manufacturing: low production costs, product

quality and performance, flexibility, product delivery

and level of innovation.

The pattern of manufacturing choice relates to

structural and infrastructural decisions in the

company to support the choice of manufacturing

capabilities (Schroeder et al., 1986; Sun and Hong,

2002). Structural decisions include choices on

facilities, technology, vertical integration, capacity,

and the factory location, while infrastructural

decisions those related to organizational structure,

quality management, workforce policies, and

information systems architecture. This research

focuses only on manufacturing tasks.

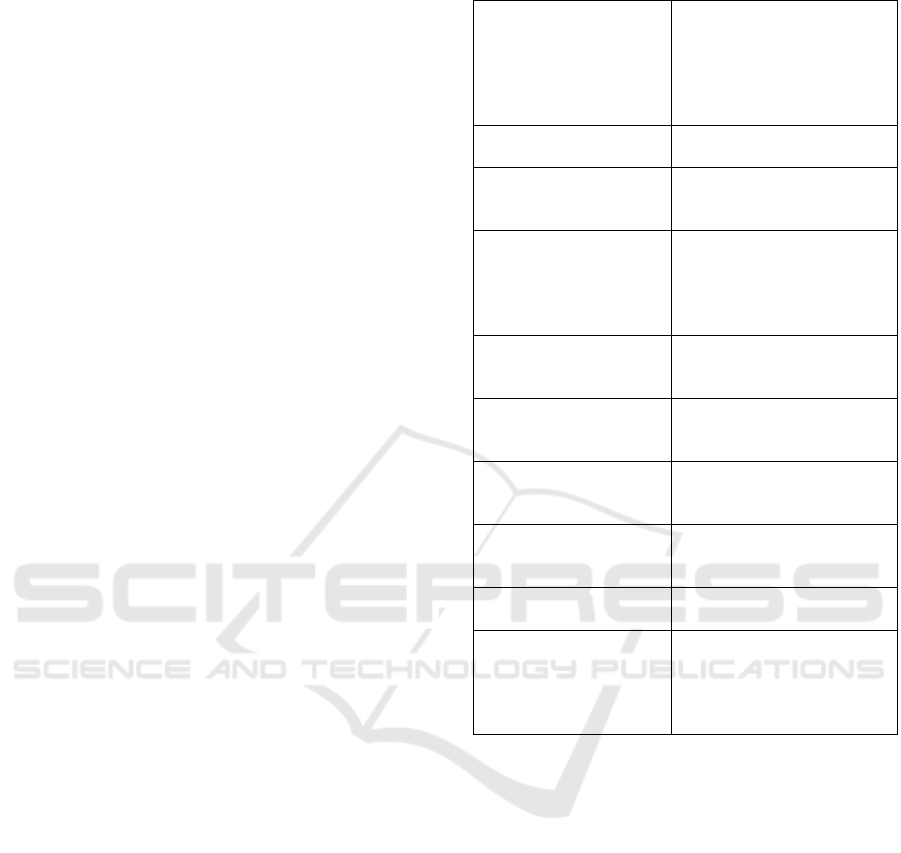

Table 1: Ten dimensions of manufacturing capability

Product Flexibility The ability to handle

difficulties and nonstandard

requests and produce

products with a variety of

shapes, choices, sizes, and

colors

Volume Flexibility The ability to quickly adjust

production capacity

Process Flexibility The ability to produce low-

cost products and varied

change products easily

Low Production Cost The ability to minimize

total production costs (such

as direct labor costs,

material, and operating

costs)

Level of Innovation/

New Product

Introduction

The ability to introduce

increased product variations

appropriately

Delivery Speed The ability to ensure order

quantities and anticipate

order delivery times

Delivery Dependency The ability to ensure order

quantities and anticipate

order delivery times

Product Quality The ability to produce

products with standard

performance

Product Reliability The ability to maximize

product damage lifetime

Design Quality The ability to provide

products with shapes,

models, and characteristics

that possess competitive

advantages

Source: Vickery et al. (1993); Oltra and Flor

(2010)

Different studies tend to use different numbers of

manufacturing task variables. For example, Miller

and Roth (1994); Vickery et al. (1993) and Oltra and

Flor (2010) used 11 dimensions, including the

dimension of marketing competence, while Sum et al.

(2004) used 8 dimensions, namely low production

costs, process and product flexibility, product quality

and reliability, speed and delivery dependency and

innovation. Vickery et al. (1993), on the other hand,

used 10 dimensions of manufacturing capability, as

presented in Table 1.

2.4 Business Strategy

Porter classifies business strategy into three types

(overall cost leadership, focus, and clear

differentiation), each of which requires commitment

and effective management of the organization. The

first strategy, overall cost leadership, appeared in the

Misfit-score Evaluation on Business and Manufacturing Strategies and the Impact on Operational Performance

171

1970s due to the popularity of the experience curve

concept (Porter, 1985). This strategy seeks to achieve

low-cost leadership through efficient construction of

existing facilities, careful and experience-based cost

reduction, strict cost and overhead control, and cost

minimization in areas such as research and

development, services, sales force, and advertising

(Ortega et al., 2012). The second strategy,"

focus," centers on certain segments or buyers with

certain products, certain markets, and certain

geographic markets. In this regard, the focus strategy

has several forms, namely the basic focus on

achieving low costs or differentiation and the basic

focus on differentiation followed by the achievement

of low costs. The third strategy “pure differentiation”

focuses more on creating something new and unique

in the products offered to consumers. Companies that

use these strategies usually focus on certain segments

(Porter, 1985; Oltra and Flor, 2010). Differentiation

strategies can be executed in various forms, such as

design or brand image, technology and features

(Ortega et al., 2012)

In contrast to Porter’s classification, Miles and

Snow (1978) categorize business strategy choices

into four typologies, namely: (1) prospector, (2)

defender, (3) analyzer, and (4) reactor. Prospector is

a strategy that emphasizes innovation and creativity

to create new products. The company always strives

to be a pioneer in competition and is willing to

compensate for internal efficiency for innovation and

creativity. A defender is a strategy to create stability

and achieve corporate survival. The company's focus

is on achieving long-term stability and maintaining its

core business without making too many strategic

changes.

The analyzer is a strategy that combines

prospector and defender. This means that the

company does not take risks in innovating, but it still

attempts to create excellence in its services to the

market. The reactor is a strategy that always focuses

on efficiency without considering environmental

changes, and organizations commonly use it without

consistent adaptation strategies (unstable).

Smith et al. (1989) and Banchuen, et al. (2017)

suggest that the four typologies of Miles and Snow

(1978) reflect the environmental complexity faced by

organizations and organizational processes from

various dimensions, such as competition, consumer

behavior, market situation and response, technology,

organizational structure, and other managerial

characteristics. On the other hand, the three

typologies of Porter (1980) only generally describe

the behavior of market competition.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 Population, Sample and Sampling

Technique

The population in this study were all furniture

factories in Central Java and Yogyakarta Special

Province (DIY). However, for the convenience of

data collection, this research focuses on companies in

the furniture centers in Jepara, Kudus, Solo,

Karanganyar, Klaten, and several companies in the

DIY area. This study uses purposive sampling by

selecting companies that employ more than 20

employees and have reached markets abroad to

ensure a certain level of awareness and proper and

continuous strategy planning.

3.2 Variables and Research

Instruments

Variables in this study include manufacturing

strategies (as measured by the dimensions of low

production costs, product quality, and reliability,

delivery, flexibility, and level of innovation),

business strategies, and factory operational

performance. Each variable is broken down into

several questions with alternative answers in the form

of strongly agree (score 5) until strongly disagree

(score 1) based on the Likert scale.

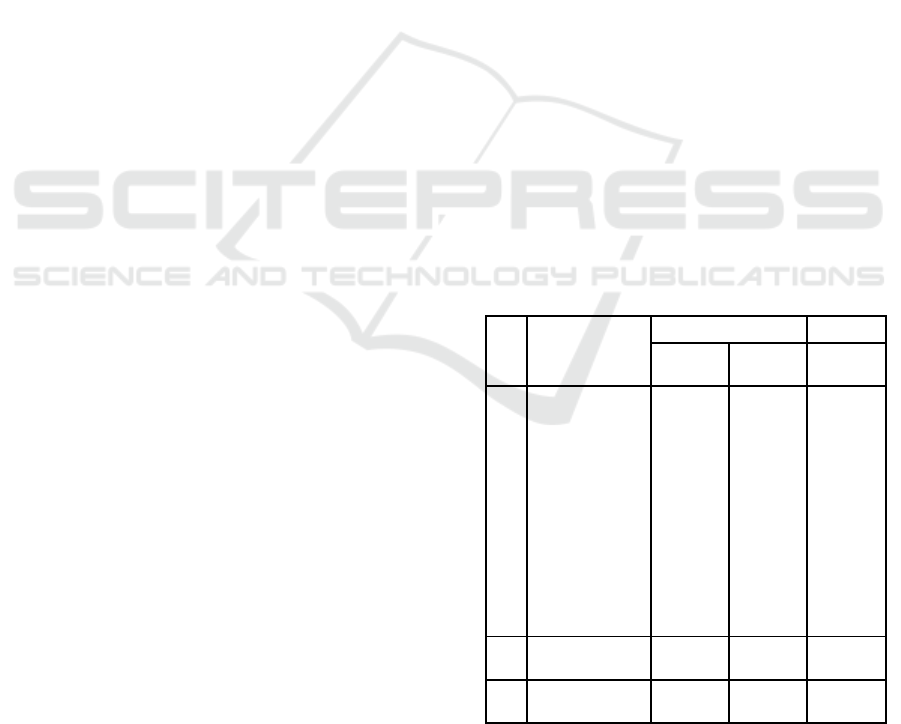

Table 2. Validity and Reliability Testing Results

No Variables

Validity Reliability

Keiser’s

MSA

Factor

loading

Cronbac

h alpha

Manufacturing

task

0.885

Low

production cost

0.633

0.726 –

0.764

0.571

1

Quality 0.729

0.643 –

0.768

0.707

Flexibility 0.738

0.698 –

0.825

0.707

Product

Delivery

0.754

0.530 –

0.806

0.743

Innovation 0.655

0.785 –

0.882

0.762

2

Business

Strategy

0.694

0.587 –

0.853

0.756

3

Operational

Performance

0,500

0.884 –

0.911

0.568

The validity and reliability of the research

instruments were tested with confirmatory factor

analysis through principal component analysis using

the Varimax rotation method. The test results indicate

ICBEEM 2019 - International Conference on Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management

172

the validity of the questions: Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

Measure of Sampling (Keiser's MSA) with criteria of

> 0.5 and factor loading values of > 0.4 (Hair et al.,

2005). Meanwhile, the reliability of each variable was

tested with the Cronbach alpha coefficient, where a

variable is considered reliable if the test results

produce the Cronbach alpha value of > 0.5. The

results of the validity and reliability testing are

presented in Table 2.

4 DATA ANALYSIS TECHNIQUE

This study uses a simple linear regression test to

answer the problem related to the misfit score and the

magnitude of the influence of variable fit from the

manufacturing strategy and business strategy on

operational performance. This regression model does

not use time-series data, and in behavioral studies, it

is not used to predict a phenomenon, but only to

explain the phenomenon, so that the classical

assumption test is deemed unnecessary. In this model,

what needs to be observed is multicollinearity,

namely the existence of a perfect relationship among

the independent variables in the regression model.

However, because this study uses Euclidian distance

scores or deviations from two independent variables,

multicollinearity does not need to be detected, and

thus the equation used is

Y= β0 + β1 Dist.X1.X2 + Ɛ1,

Dist.X1.X2 is the Euclidian distance from the

manufacturing-business strategies; Dist is the

Euclidian distance or misfit-score between variables

of manufacturing strategy and business strategy as a

contingent variable. The euclidian distance value is

calculated by summing the amount of deviation or the

difference in the ideal score for each ideal group

(Drazin and Van de ven, 1985; Meyer et al., 1993;

Priyono, 2004; Baeir et al., 2008) with the equation

of

Dist = Ʃ

√(X-id X-ac)2

X-id ideal contingency variable score

X-ac actual contingency variable score

5 DATA AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Data Quality Testing

5.1.1 Response Bias Test

Response bias test and difference tests were

performed before measuring the misfit score of the

variables from manufacturing strategy and business

strategy and testing its effect on performance.

Response bias test of control variables and research

variables was conducted to detect significant

differences between respondents who filled the

questionnaire directly and those indirectly. If the

difference between the results of the response bias

test and the difference test proved to be insignificant,

this means that the respondent's answers from the two

groups did not show any differences so that further

analysis could be carried out.

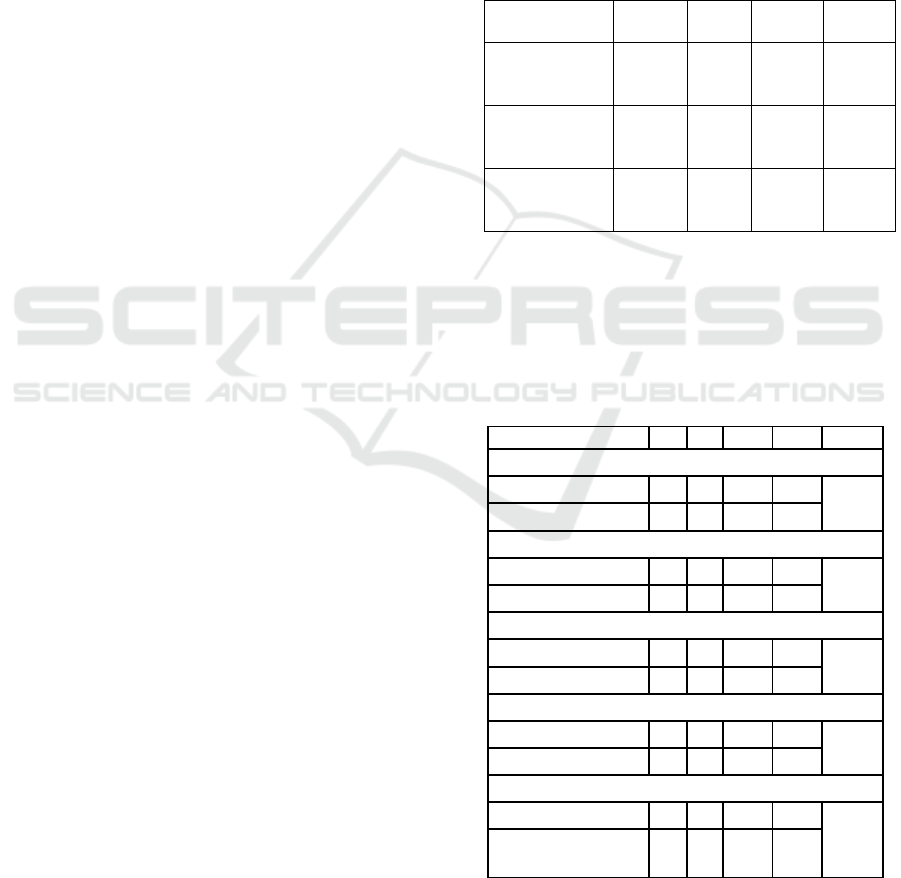

Table 3. Response Bias Test on Research Variables

Variables

Group

Codes

N F Sig

Manufacturing

Task

1

2

Total

62

37

99

0.018 0.928

Business

Strategy

1

2

Total

62

37

99

0.108 0.743

Performance

1

2

Total

62

37

99

0.816 0.369

Source: Primary data processed, 2018

Notes:

(1) Direct answers

(2) Indirect answers

Table 4. Difference Test of Manufacturing Strategy Groups

Significant at p<0.05 (**)

Manufacturing Task N Min Max Mean Total

Low Production Cost

DIY 43 3.00 12.99 10.64

9.04

Central Java 56 4.21 8.33 7.44

Quality

DIY 43 4.14 32.12 22.58

23.67

Central Java 56 6.24 34.15 24.76

Flexibility

DIY 43 7.82 30.12 28.76

29.75

Central Java 56 6.14 33.33 30.74

Product Delivery

DIY 43 7.33 16.21 15.11

14.53

Central Java 56 7.33 14.99 13.95

Level of Innovation

DIY 43 2.33 10.33 9.30

9.58

Central Java

56

2.6

6

12.99

9.86

Table 3 shows that the mean difference measured

with the F test on respondents' characteristics for each

Misfit-score Evaluation on Business and Manufacturing Strategies and the Impact on Operational Performance

173

group was insignificant with p values of > 0.05 for

education level (0.430), business experience (0.115),

manufacturing task (0.926), business strategy

(0.743), and performance (0.369). It can be concluded

that there is no significant difference in the control

variables or research variables in the two respondent

groups.

5.1.2 Difference Test of Manufacturing

Strategies

To prove that differentiators and efficient-innovators

groups have different manufacturing capability

decisions, one-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance)

was used to test it. Table 4 shows that the

manufacturing task had a significant F value with a p

value of <0.05, which means that differentiators and

efficient-innovators have different manufacturing

capability choices.

5.2 Data Description

5.2.1 Order Winner Difference

The mean value of the five manufacturing task

dimensions as the first element of manufacturing

strategy is calculated for each sample. Table 5 shows

the mean values, maximum and minimum values, and

the total mean values of each dimension.

Table 5. Statistical Description of Manufacturing Task

Group Codes

N Mean

Standard

Deviatio

n

F

Efficient-

Innovators

(1)

7

6

81.236

2

13.8452

22.492

**

Differentiato

rs (2)

2

3

86.090

9

13.7105

Source: primary data processed, 2018

5.2.2 Low Production Cost

In this dimension, the mean difference between DIY

and Central Java was relatively small. This is

supported by observations in the field where

companies in DIY and Central Java, in the production

process, do not assign special employees to handle

plant operations. Most owners carry out inspection

processes by themselves. The high mean value in DIY

may be due to the intensive technical assistance and

training organized by the relevant government

agencies. Meanwhile, in Central Java because of the

wide spread of SME's, the company's access to

training by the government agencies is fairly limited.

The ability to create efficiency may be due to the lack

of technical assistance provided by companies in

Central Java.

5.2.3 Quality

Table 5 shows that the mean value of quality

dimension was higher in Central Java. This may be

due to the positive behavior of entrepreneurs in

Central Java in training and technology mastery

development program held by the industry agency. In

contrast, entrepreneurs in DIY tend to have low

motivation to be involved in such programs. The

results of the interview with Mr. Yulianto, the

administrator of the Yogyakarta Furniture

Association, revealed that access to training was only

obtained by a few entrepreneurs who had close

relations with the agency. Training opportunities are

considered unequal.

5.2.4 Flexibility

Most entrepreneurs in Central Java and DIY are

always ready when customers request changes in

product design, quantity and quality specifications.

They produce according to customers’ requests.

However, only companies that have mass-

standardized themselves prepare to ensure the

continuity of the production process, with the use of

generators or cooperation with the State Electricity

Company (PLN) to get early notifications before a

power outage. The average value of flexibility in DIY

was higher, and this is supported by field observations

where most entrepreneurs in Central Java were

relatively individualized (not interconnected), and

most of the companies are family businesses.

5.2.5 Product Delivery

The difference in mean values of this dimension

between companies in Central Java and DIY was

relatively small. The results of interviews with

several large companies in DIY who have partnered

with logistics service companies or have been able to

independently export show that the company can

fulfill the orders of foreign buyers according to

specifications and deliver them on time.

Meanwhile, the results of interviews with several

companies in Jepara and Klaten reveal that most

companies still prioritize partnerships with local

traders. They focus on meeting the needs of local

consumers so that the culture of fulfilling orders

promptly has not been fully developed because some

local customers tend to have a high tolerance for

untimely product delivery.

ICBEEM 2019 - International Conference on Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management

174

5.2.6 Level of Innovation

The difference in mean values in this dimension

between Central Java and DIY is relatively small and

insignificant. This is consistent with the results of

interviews in the field where most product design

changes are tailored to customer demand. The

development of information technology makes it

easier for companies to access the development of

product models quickly so that understanding of

market preferences can be understood quickly.

5.3 Determination of Misfit Score with

Euclidean Distance

The alignment or ideal profile is the fit between

capability choice decisions in the manufacturing and

those in business strategies as the vertical alignment.

Alignment In efficient-innovators and differentiators

groups and alignment in defenders and prospectors

groups is based on theoretical approaches, ideal

profile scores for differentiators were 35

(prospectors) and efficient - innovators were 7

(defenders).

The results of descriptive statistical processing of

the manufacturing strategy variables show that the

mean, standard deviation, and range values were

85.0409, 13.71, and 44.37, respectively. In the data

processing for regression analysis, the researchers

used the mean split of manufacturing strategy

elements. For manufacturing tasks (choice of

capabilities in manufacturing), scores for each group

are distinguished by mean values. If the score is

above 85.0409, the respondents’ answers will be

grouped as differentiators. Furthermore, the ideal

configuration of the group is supported by the

prospector's category. Conversely, efficient -

innovators are groups of respondents whose values

are below 85.0409, which is more aligned with the

defenders. Then, to hypothesis testing using the misfit

score for each strategy, groups and misfit score is

calculated with euclidian distance.

5.4 Regression Analysis Results

5.4.1 Efficient – Innovators Group Analysis

Efficient-innovators are groups of companies that

tend to defend to achieve efficiency (through low

production costs) and are less aggressive in marketing

or creating new markets. The taxonomic approach

developed by Sum, Kou, and Chen (2004) describes

SME groups in Singapore as efficient - innovators

because their main focus is achieving efficiency. To

always be competitive, companies are always

required to innovate, but these innovations do not

emphasize their product uniqueness but merely

follow the market trend so that innovation costs can

be minimized. Competence for product delivery,

especially the speed of product delivery, is also

prioritized.

A total of 76 companies are classified as efficient

- innovators because they are oriented towards

achieving production efficiency. However, based on

interviews, there are still many companies that do not

carry out inspections at the plant continuously, even

though they are aware that production process

activities are not optimal. The lack of efficiency in the

production process is caused by the fulfillment of

orders by trial and errors in modeling, lack of

technicians or skilled employees, and weak mastery

of imported machinery and equipment. Many

companies bear considerable engine maintenance

costs because the engine components must be

imported.

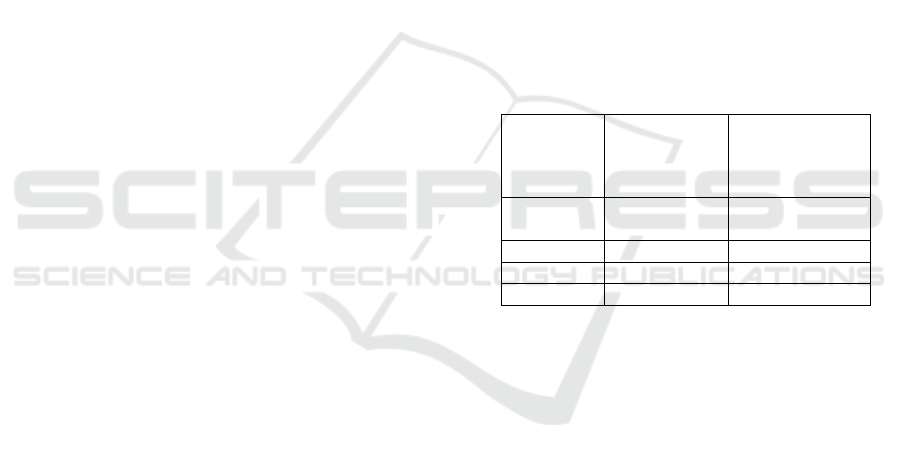

Table 6. Regression Results

Statistical

Values

Defender_Eff

icient-

Innovator

(n = 76)

Prospector_Diff

erentiator

(n=23)

Regression

coeff. (b)

0.235 - 0.390**

tcount 2.075 - 2.416

Constant 5.481 7.536

R square 0.235 0.090

**Sign p<0.05

Table 6 shows the results of the t test. The t-count

value was 2.075, while the t-table value was 2.680

(with a significance value of 5%, df = n - 2 = 76-2 =

74). The t-count result was lower than t-table. In

addition, the regression coefficient value was 0.235

(positive) and not significant (p> 0.05), which means

that there is no fit between manufacturing task and

business strategies in the defender_efficient

innovators group so that their effect on operational

performance cannot be proven.

The result of this study is consistent with that by

Ortega et all (2012), which identified that efficiency

failure in the innovation development in companies

was largely triggered by the company's inability to

synchronize their business with their partners'. Most

furniture industries in Central Java and DIY, in the

development of product models, are often constrained

by frequent delays in the supply of raw materials,

because business owners rarely share information

with their business partners such as log and sawmill

suppliers. The farmers' role as log suppliers is not

Misfit-score Evaluation on Business and Manufacturing Strategies and the Impact on Operational Performance

175

properly understood by the manufacturers, and thus

triggers delays in fulfilling orders. Bancheun, et al

(2017) suggest that the creation of effective

innovations in the field of production can be

supported by the collaborative development of

production plans with related parties such as raw

material suppliers.

Most SMEs oriented to local markets are included

in the efficient - innovators group and they face

different problems, for example, sluggish domestic

market conditions that force them to reduce

production capacity. Some companies fail to develop

innovations because of weak employees' ability and

skill. The findings in the field prove that the defender

groups fail to develop innovations efficiently because

they are short-term, rather than long-term oriented.

5.4.2 Differentiator Group Analysis

Differentiator is a group of companies that always

aggressively market their products and expand their

markets, have strong motivation to invest in

production expansion for the long term, and always

create product innovation. The group also prioritizes

product quality and reliability, focusing on creating

new products or product uniqueness despite the high

production costs. Table 6 shows the regression

coefficient (standardized) of - 0.390 (negative) and

not significant (p> 0.082), which means that there

was no fit between the decision of capability choices

and strategy in the groups. This result is supported by

a relatively small misfit score.

Based on the results of interviews and

observations, the lack of fit between the decisions of

capability choices and business strategy is because

the companies in this group are less aggressive in

marketing and expanding market share. For example,

only a few companies in DIY market their products

online. Many companies have websites but the

information is not up to date. Most companies still

rely on third parties for export management, although

some centers already have a place for joint business

development such as cooperatives. However,

cooperative activities are still relatively limited

because the entrepreneurs' interest to attend such

cooperative programs are still very weak.

The small number of companies in the group is

consistent with the reality in the field, where only a

few companies have succeeded in establishing

partnerships with foreign buyers. This indicates that

there are still few companies capable of producing

high quality and reliability products. The low degree

of fit may also be caused by the reluctance of

companies to invest long-term and the small amount

of funds available for quality improvement, even

though banks have eased financial access to the

companies. This is consistent with the results of

Bancheun et al (2017) study which found that most

exporters experienced a business failure because in

their efforts to fulfilling foreign orders, companies

used bank loans for working capital. The slow

turnover of money in dealing with foreign buyers

triggers a large bank interest expense. A number of

export-oriented companies are reluctant to invest in

long-term because of the slow turnover of income and

hence cause an imbalance between profit margins

received and bank loan interest. Most company

partners make payments after the order is delivered,

when in fact the production process until delivery

takes up to 3 to 4 months. The interest expense that

must be borne for these four months is not covered by

the profit margin received.

6 IMPLICATIONS FOR

PRACTITIONERS

One interesting issue to study further regarding the

ideal configuration theory is the addition of new

elements of manufacturing strategy, such as structural

and infrastructural decision elements that fit the

market aspects or the process choice used. In

addition, configurational theories on heterogeneous

samples and companies other than the furniture

industry also need to be further investigated. The

reality in the field shows that the failure of furniture

product exports is caused by the companies' inability

to complete export documents, one of which is a

document that guarantees that the wood raw materials

used for the products are obtained from sustainable

forest management. The inability of business owners

to complete the documents is triggered by the weak

documentation by log and sawmill suppliers in the

chain of custody of raw material sources. This is

predicted by the researchers as one of the causes of

the low misfit-score, and it is difficult to predict the

magnitude of the influence of the fit of the choice of

manufacturing capabilities with a business strategy

on performance. In reality, the incompleteness of

export documents has caused entrepreneurs to

experience difficulties in developing capability

choices in manufacturing to support their business

strategies. This problem requires support from

various stakeholders to create the sustainability of the

upstream-downstream furniture supply chain.

ICBEEM 2019 - International Conference on Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management

176

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The Directorate of Indonesian Higher Education

funds this study on a doctorate dissertation research

grant in the fiscal year 2018.

REFERENCES

Baier, C., Hartmann, E. and Moser, R. (2008), “Strategic

alignment and purchasing efficacy: an exploratory

analysis of their impact on financial performance”,

Journal of Supply Chain Management, Vol. 44 No. 4,

pp. 36-52.

Bancheun, P., Sadler, I. and Shee, H. (2017), “ Supply

Chain Collaboration aligns Order Winning Strategy

With Business Outcomes, IIMB Management Review,

Vol. 29, 109-121

Burn, S.T. and Stalker, G.M., (1961), “ The management

of innovation”, London: Tavistock Publication

Chandler, A.D.Jr.,(1962), “Strategy and Structure”,

Cambridge MA: Mitpress.

Child, J. (1975), “ Managerial and organizational factors

associated with company performance”, Journal of

Management Studies, Vol.12, pp. 12-27

Doty, D.H., Glick, W.H. and Huber, G.P, (1993), “ Fit,

equuifinality and organizatinal effectiveness: atest of

two configurational theories”, Academy of

Management Journal, Vol.36, pp.1196-1250

Drazin, R., and Van De Ven, A.H., (1985), “Alternatives

Form of Fit in Contigency Theory”, Administrative

Science Quarterly, Vol.30:p. 514-539

Ferdows, K. and De-Meyer, A. (1990), “Lasting

improvements in manufacturing performance: in search

of a new theory”, Journal of Operations Management,

Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 168-84.

Galbraith, J.R. (1973), “Designing Complex

Organizations”, Addison-Wesley, Reading.

Galbraith, J.R. and Nathanson, D.A. (1978), “Strategy

Implementation: The Role of Structure and Process”,

St. Paul, Minn: West

Hage, J. and M.Aiken (1969), “ Routine technology, social

structure and organizational goals”, Administrative

Science Quarterly, Vol. 14, pp.366-376

Hayes, R.H. and Pisano, G.P. (1994), “ Beyond world-

class: the new manufacturing strategy”, Harvard

Business Review, Vol.72, No.1, pp. 77-86

Kusmantini, Titik; Guritno, Adi Djoko and Rustamaji, Heru

(2014), “ Risk Mitigation Action With HoR Framework

as Effort to Build a Robust Supply Chain in Furniture

Industry’, International Multidisiplinary Conference

Proceeding, UMJ, ISBN 978-602-17688-1-5,

November 12-13

Lorsch, J.W and Morse, J.J. (1994), “Organizations and

their members a contigency approach”, New York, NY:

Harper and Row

Meyer, A.D., Tsui, A.S. and C.R. Hinings (1993),

“Configurational approaches to organizational

analysis”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol.36,

No.6, pp.1175-1195

Miles, R.E dan C.C. Snow (1978), “ Organizational

strategy, structure and process”, New york, NY: Mc

Grow Hill

Miller, J.G. and Roth, A.V., (1994), “A taxonomy of

manufacturing strategies”, Management Science, Vol.

40 (3):p. 285-304

Mintzberg, H. (1978). “Pattern in Strategy Formulation”,

Management Science,Vol.24 (9):p. 934-948.

Oltra M.J and Flor, M.L (2010), “ The Moderating Effect

of Business Strategy on The Relationship Between

Operation Strategy and Firm’s Result”, International

Journal of Operation and Production Management,

Vol.30, No.6, pp.612-638

Ortega, C.H., Garrido-Vega, P. and Antonio, J. (2012), “

Analysis of interaction fit between manufacturing

strategy and technology management and its impact on

performance”, International Journal of Operation and

Production Management, Vol.32(8), 958-981.

Porter, M.E. and Millar, V. (1985), “How information gives

your competitive advantage”, Harvard Business

Review, July-August, pp. 149-160

Priyono, Bambang Suko (2004), “ Pengaruh Derajat

Kesesuaian Hubungan Strategi, Struktur, Karir dan

Budaya Organisasi Terhadap Kinerja Perusahaan”,

Disertasi, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Tidak

Dipublikasikan.

Roth, A.V. and Miller, J.G., (1992), “Sucsess Factors in

Manufacturing”, Business horizon, Vol.35, No. 4, pp.

73-81

Schroeder, R.G., Anderson, J.C. and Cleveland, G. (1986),

“The content of manufacturing strategy: an empirical

study”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 6 No.

4, pp. 405-15.

Shavarini, S.K., Salimian, H., Nazemi, J. and Alborzi, M.

(2013), “ Operation Strategy and Business Strategy

Alignment Model (Case of Iranian Industries),”

International Journal of Operation Management, Vol.

33, No.9, pp. 1108-1130.

Skinner, W. (1969), “Manufacturing – Missing Link in

Corporate Strategy”, Harvard Business Review,

Vol.47(3):p.136-145

Skinner, W. (1978), “Manufacturing in The Corporate

Strategy”, New York: Wiley

Smith, K.G., Guthrie, J.P. and Chen, M. (1989), “Strategy,

size and performance”, Organization Studies, Vol. 10

No. 1, pp. 63-81.

Sum, C., Kow, L. S. and Chen, C.S. (2004). A taxonomy of

operations strategies of high performing small and

medium enterprises in Singap. International Journal of

Operations & Production Management, 24(3/4), 321–

345.

Sun, H. and Hong, C. (2002), “The alignment between

manufacturing and business strategies: its influence on

business performance”, Technovation Journal, Vol. 22,

pp. 699-705.

Swink, M., Narasimhan, R. and Kim, S.W. (2005),

“Manufacturing practices and strategy integration:

effects on cost efficiency, flexibility, and market-based

Misfit-score Evaluation on Business and Manufacturing Strategies and the Impact on Operational Performance

177

performance”, Decision Sciences, Vol. 36 No. 3, pp.

427-57.

Vachon, S., Halley, A. and Bealieu, M. (2009), “ Aligning

competitive priorities in the supply chain: the role of

interactions with suppliers”, International Journal of

Operation and Production Management, Vol.29(4),

322-340.

Venkantraman, N. (1990), “Performance implications of

strategic coalignment:a methodological perspective”,

Journal of Management Studies, Vol.27, pp.19-41

Venkatraman, N. and Camillus, J.C. (1984), “Exploring the

concept of fit in strategic management”, The Academy

of Management Review, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 513-25.

Vickery, K.S., Droge, C. dan Markland, R.E., (1994),

“Source and Outcome of Competitive Advantage: An

Exploratory Study in Furniture Industri”, Decision

Science Vol.25(5):p. 679-684

Ward, P.T. and Duray, R. (2000), “Manufacturing strategy

in context: environment, competitive strategy and

manufacturing strategy”, Journal of Operations

Management, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 123-38.

Ward, P.T., Mc.Creery, J.K., Ritzman, L.P. and Sharma, D.,

(1998) “Competitive Priorities in Operation

Managements”, Decision Science, Vol.29 (4): 1035-

1046

Ward, P.T., McCreery, J.K. and Anand, G. (2007), “

Business strategies and manufacturing decisions – an

empirical examination linkages”

ICBEEM 2019 - International Conference on Business, Economy, Entrepreneurship and Management

178