Autonomous Learning Readiness and English Language Performance of

English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Libyan Secondary School Students

Siti Maziha Mustapha and Fadhil Tahar M Mahmoud

Infrastructure University Kuala Lumpur,Kajang, Malaysia

Keywords:

Autonomous Learning, English Language Performance, EFL Libyan students.

Abstract:

This study examined students‘ readiness to be autonomous and how it connected and influenced their English

language performance. The research design was a mixed method (convergent parallel design). The data were

collected from a Libyan Secondary school in Malaysia. 103 students were selected to answer the questionnaire

and 10 for interviews. All the data collected were analysed by using the (SPSS) version 24 and NVivo pro

10. The findings showed that the Libyan secondary school students were ready to carry out autonomous

learning. Students preferred to learn English outside the classroom and they aimed at improving their mastery

of the English language to an advanced level. Gender was significantly correlated to learner autonomy and

had a moderate influence on learner autonomy. Students’ autonomous learning readiness was significantly

correlated to English language performance. Recommendations were made to enhance students’ autonomous

learning

1 BACKGROUND OF STUDY

In the 1970s, the Council of Europe’s Modern

Languages started a project which was aimed at

giving opportunities to adults to continue learning a

foreign language or better known as lifelong learning.

Since then, the theory and practice of autonomy

in language learning has gained momentum and

importance. Studies on learner autonomy began to

be published by researchers (Benson, 2001a; Benson,

2001b; Benson, 1997; Dam, 2011; Dickinson, 1995;

Holec, 1981; Little, 1990; Palfreyman and Smith,

2003).

(Benson, 2001a) explained that autonomy is about

learners’ readiness to be in charge of their own

learning. The learners “initiate and manage their

own learning, set their own priorities and agendas

and attempt to control psychological factors that

influence their learning”. Learning English has

been a challenging task for many people around the

world especially for the Libyan students. (Sawani,

2009) stressed that the Libyan education system

has been suffered from lack of manpower. There

were not enough English teachers. This created a

situation where many learners are placed together

in a class. The big class size limits interaction

opportunities among learners or reduces opportunities

for teachers to use the English language in the

classroom. Therefore, encouraging students to be

autonomous would serve as an economical solution

for the lack of manpower. By being autonomous

students can compensate for the lack of opportunities

to use English in class by taking control of their own

learning and creating their own opportunities to use

English (Sawani, 2009). Over the years, there have

been many studies on learner autonomy which were

mainly focussed on the Western context. However,

studies on Libyan students are very limited. Thus,

this study attempted to investigate Libyan students’

readiness toward learning English autonomously and

its effect on their English language performance.

2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

The teaching of English in Libyan schools begins

from the fifth grade. The English language

curriculum is normally designed to serve all students’

needs in learning the four skills, listening, speaking,

reading and writing. The teachers are supposed to

use the communicative approach in conducting the

English classes. However, many teachers still use

grammar-translation method in teaching the language

skills. In class, lessons are focused mainly on English

grammar rules rather than the other language skills.

The grammar-translation method clearly played a

Mustapha, S. and Mahmoud, F.

Autonomous Learning Readiness and English Language Performance of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Libyan Secondary School Students.

DOI: 10.5220/0009060301090116

In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Social, Economy, Education and Humanity (ICoSEEH 2019) - Sustainable Development in Developing Country for Facing Industrial

Revolution 4.0, pages 109-116

ISBN: 978-989-758-464-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

109

major role in the English classroom in the past and

remains in practice to the present day (Altaieb, 2013).

EFL Libyan learners struggle to memorize English

grammar rules and are given less opportunities to

use and be exposed to the real language. Hence,

the learners basically learn two things: English word

forms and their Arabic translation.

In the experience and observation of the

researchers, English language learners in preparatory

and high school had to memorize the grammatical

rules and lists of new vocabulary given by the teachers

on a daily basis. Students were forced to memorize

large number of new vocabulary items with Arabic

translation during the whole course. The learners

became less motivated to be exposed to and learn the

real language. There is a need to consider encourage

and enable learners to take more control of their

learning so their performance in the English language

could be improved. (Benson, 2001a) stressed the

importance and the need to implement practices

which motivate learners to be more autonomous

in all aspects of their learning, will help them

to become better language learners. The present

study aims to examine whether Libyan learners are

ready and willing to accept their responsibility of

learning the English language autonomously, whether

their gender influences their autonomy and whether

their autonomy influences their English language

performance.

3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

At a broader level, the current study aimed

to investigate the learner autonomy and how it

influences students‘ English language performance.

The following are the research question:

• What are the perceptions of students toward

autonomous learning?

• To what extent does gender influence students’

autonomous learning readiness?

• Is there a significant relationship between

autonomous learning readiness and English

language performance of students

4 LITERATURE REVIEW

In language learning, learner autonomy concept plays

a significant role. An emphasis is put on the new

form of learning which enables learners to direct

their own learning (Orawiwatnakul and Wichadee,

2017). A main element of language learning that is

considered significant is learner autonomy and it has

been given a great deal of consideration from second

language researchers and practitioners over the years

(Dam, 2011). According to (Gardner et al., 1996)

autonomous language learners have the ability to plan

and do their own learning to meet the goals they

set for themselves. Therefore, acquiring that how to

learn is an important component of all self-sufficient

learning schemes (Little, 2007), shows progress, and

interprets individual learning performance (Benson

et al., 2014). These studies have tended to focus on

examining the readiness of learner autonomy rather

than the behavioural intention to complete a course

(Rienties et al., 2012).

There are few empirical researches investigating

whether Asian students have the tendency for

autonomy. (Chan et al., 2002) conducted a study

and distributed questionnaires to 508 university

students in Hong Kong to find out more on this

issue, taking the relationship between autonomy and

motivation into consideration. Their development of

the questionnaire was based on Holec’s (1981) idea

of autonomy The results of the study showed that

students had readiness for autonomy to some extent

and motivation seemed to be a requirement for their

autonomy. However, it was not clear whether these

results can be generalized to Asian students in other

contexts, who have less opportunity to use English

outside the class.

(Rungwaraphong, 2012) examined readiness for

autonomy in students at a university in Thailand.

He investigated three areas which were learner

autonomy; learner’s perception of teacher’s roles and

their roles, locus of control and strategies they used

in learning. He found that learners took responsibility

for their learning both due to them being intrinsically

responsible and also being coerced by some other

external factors. (Richards, 2015) identified two

critical dimensions in order to be successful in

learning a second language: the activities inside the

classroom and the activities outside of the classroom.

Previous studies such as (Fathali and Okada, 2016),

(Lai et al., 2011), and (Yoon, 2012) provided proof

that out-of-class study played a major role in language

learning process and it helped learners become

proficient in many ways. (Mobarhan et al., 2014) and

(Reinders, 2014) found self-determined behaviour

had a major influence on out-of-class learning.

The core debate and emphasis behind why

students or learners may be made autonomous and

not dependent on teachers is because autonomous

learners are better engaged in learning and are

better in end results compared to others. In

addition, such learners are more motivated towards

ICoSEEH 2019 - The Second International Conference on Social, Economy, Education, and Humanity

110

learning, intrinsically. (Hamilton, 2013) stated that

in cases when learners are cognitively connected in

learning and solving problems, they become better

at maintaining robust approach in making effective

decision and problem solving. Accordingly, such

learners are also very good at developing attitudinal

resources to overcome any transitory setbacks.

Engaged autonomous learners are more effective in

learning any language which also enables them to

develop productive and receptive skills for better

command over the language. In an overall manner,

they are better learners compared to conventional

classroom set ups. Notably, literature on the topic has

also highlighted that leveraging autonomy to learners

is one of the basic individual rights. According to

(Ismail et al., 2013) such freedom towards learning

requires holistic access to notes, goals, materials,

curriculum, methodology and progress of learning

in order to take complete responsibility of learning.

Being independent of the teachers does not refer to

full autonomy as students in distance learning courses

also have no teaching supervision yet still they are

restricted through some processes and strategies.

Alongside this, it is also accepted that attainment

of complete autonomy is nearly impossible and too

idealistic when it comes to any Arabian economy.

Instead, different ranges and degrees of autonomy can

be made possible in different cultures. According

to (Macaro, 1997), this is known as functional

autonomy which refers to autonomy in realtion to

some functions. (Macaro, 1997) explained that

autonomy in language learning occurs when learners

manage to obtain significant cognitive learning skills

through which they can actively reproduce and re-use

such skills to further master the language. In simple

words, it entails to the acquisition of knowledge and

the strategies necessary to enable learning of a subject

matter.

According to (Holec, 1981), as mentioned in

(Little and Dam, 1998) autonomy in learning asserts

that learners take responsibility and accountability of

their learning in all aspects positively. They may work

on setting goals and targets for themselves and choose

the right strategies for their learning.

There have been Libyan studies relating to

autonomy and English language learning. (Emhamed

and Krishnan, 2011) and (Abukhattala, 2016)

conducted studies on using language games in the

EFL Libyan classroom. (Aldabbus, 2008) studied

teachers’ positive attitudes towards learner-centred

approach. Students and teachers readiness for learner

autonomy was also investigated (Elmahjoub, 2014).

However, the researchers found that most of the

attempts which had been made towards implementing

these new ideas were not successful and many

difficulties have been stated. The findings of a

recent study conducted by (Jha, 2015) revealed that

autonomous language learning was rarely used in

the Libyan context. Teachers’ lack of understanding

of this concept and its principles and practices can

be one of the possible reasons for not promoting it

successfully to the Libyan students.

Based on previous studies, it is assumed that

students already have a certain degree of autonomy,

but each learner is different and that teachers should

employ different approaches to promote autonomy. In

English as a Foreign Language (EFL) environment,

obtaining a high score in English tests is an indicator

of good achievement. There were a few researches

into autonomy and language proficiency. (Sakai and

Takagi, 2009) found positive correlation between EFL

Japanese student readiness to autonomous learning

and their English proficiency. The findings of (Zarei

et al., 2015) revealed that language proficiency is not

an influential factor for developing learner autonomy.

It has been established that that learners’ gender

has an influence on language learning (Brown,

2007). In his study, Brown found that there were

differences between males and females in terms

of their language use which reflected that learners

have different choices when it comes language

learning. Over the years, the studies delving into

learner autonomy are limited when it comes gender

. (

¨

Ust

¨

unl

¨

uo

˘

glu, 2009) investigated Turkish university

students’ autonomy in relation to gender and found

that there was no significant difference in the

autonomy perception between students of different

gender reflected that learners have different choices

when it comes language learning. The studies delving

into learner autonomy are limited when it comes

gender. (

¨

Ust

¨

unl

¨

uo

˘

glu, 2009) investigated Turkish

university students’ autonomy in relation to gender

and found that there was no significant difference

in the autonomy perception between students of

different gender.

5 METHODOLOGY

The current study used the mixed method approach to

collect and analyse data. A convergent parallel design

was utilized. In this design, researcher collected

the quantitative and qualitative data, then analysed

the data separately. Finally results of both were

compared to see whether the findings were confirming

or disconfirming each other (Creswell, 2013).

A Libyan secondary school that follows the

Libyan national curriculum which taught all the

Autonomous Learning Readiness and English Language Performance of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Libyan Secondary School

Students

111

courses in Arabic language excluding English

language subject were selected. The target

respondents were EFL Libyan secondary school

students in Malaysia. There were 140 students

as a total for the enrolment. 103 students were

selected to answer the questionnaires. The sample

size was chosen based on Krejcie & Morgan’s table

(Krejcie and Morgan, 1970). Based on their table,

required sample size for any population of a defined

(finite) size N= 140 was 103. 49 students were

male and 54 were female. The students have learnt

English for more than four years on average. Based

on the interviews conducted, the researcher reached

saturation point with the 10 informants.

The first instrument that was used in this study

was a questionnaire that was adopted from (Chan

et al., 2002). It was used to find out EFL

Libyan students’ readiness for autonomous English

language learning. The second instrument was

student interview to investigate their perceptions to

the learning autonomy. Lastly students’ performance

measurement was determined by using their results in

the English language subject.

The instrument for this study was piloted. The

reliability of the instrument was checked and the

Cronbach’s alpha was 0.781. SPSS statistical package

for social science version 24 was used for data

analysis and interpretation. NVivo Pro version 10

was used to analyse qualitative data from student

interviews.

6 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To answer the first research question, the data

collected from the interviews with the students were

transcribed verbatim and analysed using NVivo.

Research Question 1: What are the perceptions of

students toward autonomous learning? To investigate

the perceptions of students toward autonomous

learning they were asked to respond to the following

questions:

• Which do you prefer: learning English in a class

or learning English on your own out of class?

• Do you do any activity to learn English out of

class? If yes, please tell me what are the activities

you have used to learn English?

It was found that all 10 students interviewed

preferred to learn English on their own, out of class

to improve their English instead of learning English

in a class as indicated in Table 1 and 2.

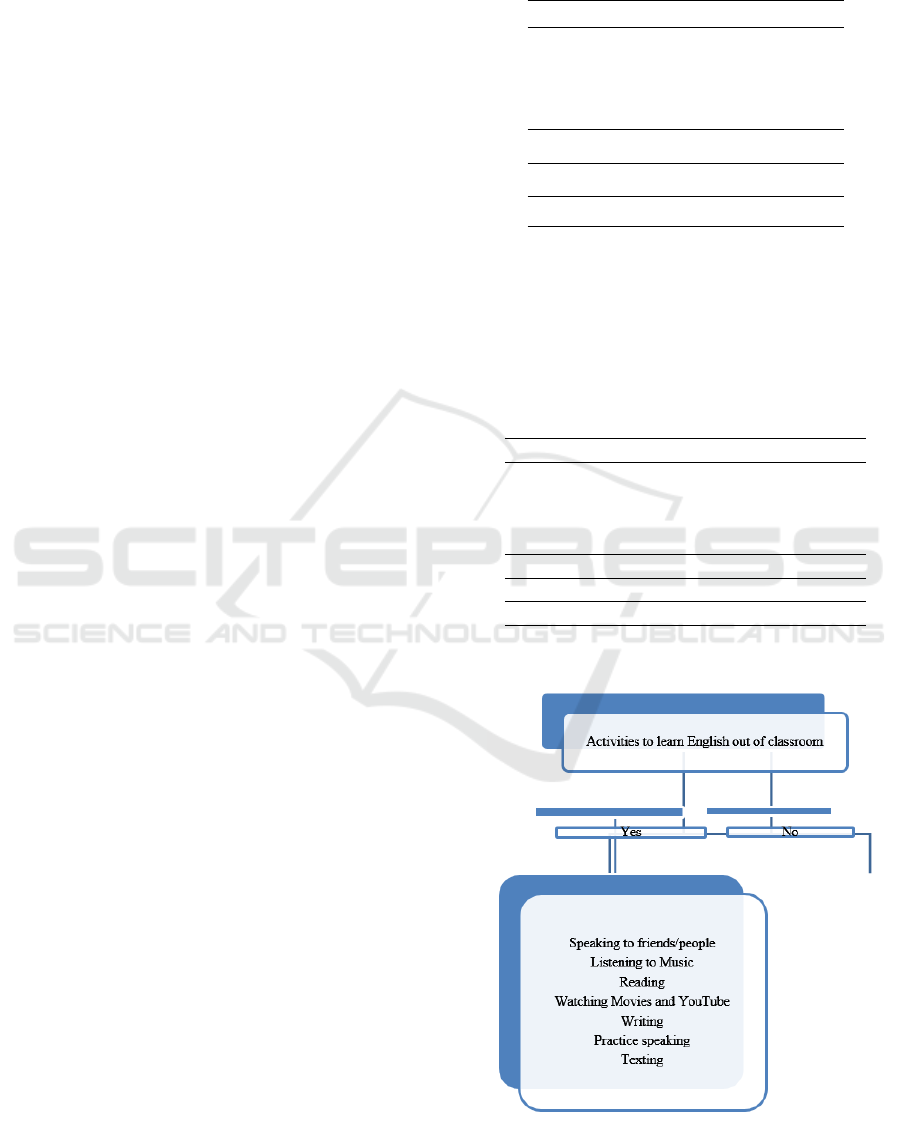

The students answered that they carried out

activities like speaking to friends or people, listening

Table 1: Themes Frequency: Perceptions of students toward

autonomous learning

Themes Refs

Which do you prefer: learning

English in a class or learn

English on your own out of

class?

Sub-Themes

In class 0

Out of class 10

to music, reading, watching movies and YouTube,

Writing, Practice speaking and texting (Figure 1).

They spent an average of 4 to 6 hours in a week doing

the reported activities.

Table 2: Themes Frequency: Activities to learn English out

of classroom

Themes Refs

Do you do any activities to learn

English out of class? If yes, please

tell what are the activities you use

to learn English?

Sub-Themes

Yes 10

No 0

Figure 1: Activities carried out outside of class

When asked on the activities they did and how

ICoSEEH 2019 - The Second International Conference on Social, Economy, Education, and Humanity

112

much time they spent in a week to carry out the

activities, the students gave the following answers:

Interviewee 1 : Yes, I do learn English out of

classroom. Like I use to talk to friends and listen

music. In average I used to spend about 4 to 5

hours in learning English in a week.

Interviewee 2: Yes, I learn English out of class.

I read stories novels and talk in English with my

friends for about 5 hours.

Interviewee 3: Yes, along with classroom

learning I use to learn English out of classroom

also. In form of talking with friends, reading

novels, watching movies and you tube. I spend

5 hours in learning English.

Interviewee 4: Yes, I speak with my friends and

read books. About 8 hours.

Interviewee 5: Yes, I love to learn English out of

class like speaking with people and friends, not

mush but 3 to 4 hour in average.

Interviewee 6: Yes, I talk to friends and read

books. About 7 hours.

Interviewee 7: Yes, chatting or texting with

friends. About 4 to 5 hours.

Interviewee 8: Yes, talking with friends. There is

no limit to hours.

Interviewee 9: No limit for time.

Interviewee 10: Yes, talk to friends. Around 6

hours.

The students were then asked whether they

enjoyed learning English and what level of English

do they want to achieve before they enter university.

Interestingly, all of them admitted to enjoying

learning English, except for one student who admitted

that learning English was hard but interesting (Table

3).

Table 3: Themes Frequency: Feelings towards learning

English

Themes Refs

Do you enjoy learning English?

Sub-Themes

Enjoy 9

Hard 1

The students were also asked to what level

of English they wanted to achieve before entering

university. It is interesting to note that the students

were motivated to learn English until they reached

advanced level before enrolling in the university.

Only 1 student preferred to reach intermediate level.

Details of the answers given during the interviews

were as follows:

Interviewee 1 : Yes, I enjoy. I want to achieve

advance level. Be fluent in English.

Interviewee 2: Yes, I do enjoy. I want to learn up

till advance level before going to university.

Interviewee 3: Yes, I enjoy. I want to learn up till

advance level.

Interviewee 4: Yes, I enjoy. I want to take

advance level.

Interviewee 5: It’s hard but interesting. I want to

learn advance level.

Interviewee 6: Yes, I enjoy. I want to learn

advance level.

Interviewee 7: Yes, I enjoy. I want to achieve

advance level. Be fluent in English.

Interviewee 8: Yes, I enjoy. Intermediate level of

English is fine for me.

Interviewee 9: Yes, I enjoy. I want to learn up till

advance level.

Interviewee 10: Yes, I enjoy. I want to earn

advance level.

Majority of the students’ responded positively

and showed their willingness and readiness to

learn English autonomously. The interview session

revealed that the learners were ready to be

autonomous because majority had carried out

activities outside the classroom to learn English. It

indicated that they accepted the responsibility of

learning. When asked whether they wanted to learn

English out of class room or inside the class learning,

and what were their preferences or choices to learn

English language? In answering these questions,

all ten students gave positive response that they

preferred to learn out of the class by using various

methods like speaking with friends, listening to

English music, reading English magazines, books and

novels. (Richards, 2015) have categorized language

learning into two dimensions: what goes on inside the

classroom and what goes on outside of the classroom

which seemed to be more interesting from learners’

perspective. This study confirms the findings

from previous studies that provided evidence that

out-of-class study has a significant role in language

learning as it improved performance (Fathali and

Okada, 2016; Lai et al., 2011; Yoon, 2012) and

self-determined behaviour motivated students to learn

out of classroom (Mobarhan et al., 2014; Reinders,

2014).

To test the extent of the influence of gender on

learner autonomy, Pearson correlation was carried

out.

Autonomous Learning Readiness and English Language Performance of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Libyan Secondary School

Students

113

Table 4: Gender and Learner Autonomy Readiness

Correlation

Gender LA

Gender

Pearson

Correlation

1.000 .598**

Sig. (2-tailed) .002

N 103 103

Learner Autonomy

Pearson

Correlation

.598** 1.000

Sig. (2-tailed) .002

N 103 103

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

A Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient

was computed to assess the relationship between

gender and learner autonomy readiness of students.

Table 4 shows that there was a positive correlation

between the two variables, r = 0.498, n = 104, p =

0.002. Overall, there was a moderate, positive and

significant correlation between gender and learner

autonomy. This finding contrasted the findings from

(

¨

Ust

¨

unl

¨

uo

˘

glu, 2009).

Research Question Three Is there a significant

relationship between autonomous learning readiness

and English language performance of students?

A Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient

was used to analyze the relationship between

students’ autonomous learning readiness and English

language performance.

The results showed in Table 5 indicated that

Autonomous Learning Readiness had a positive

significant relationship (r = 0.791, p = 0.000) with

English Language Performance. The Results showed

that the p-value is smaller than (P<0.05). The results

proved that overall, there was a significant, strong and

positive correlation between autonomous learning

readiness and English language performance.

Table 5: Learner Autonomy and English Language

Performance

LA ELP

LA Pearson Correlation 1.000 .711**

Sig. (2-tailed) .000

N 103 103

ELP Pearson Correlation .711** 1.000

Sig. (2-tailed) .000

N 103 103

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level

(2-tailed).

Increases in autonomous learning readiness

were correlated with increases in English language

performance. This is in line with the findings from

(Rienties et al., 2012). The findings of the research

indicated the students’ readiness towards outside the

classroom dominates at large in comparison with the

classical view of classroom learning. A large number

of students either interviewed were more motivated

towards out of classroom learning. However, there

were a few students who found learning English

difficult but interesting.

The students’ experience of learning English was

on average above four years which means that all the

students have a basic level knowledge and mastery

of the English language. That could explain their

confidence to learn English on their own which

was reflected in their readiness to learn English

autonomously. (Little, 2007) and (Benson et al.,

2014) stated that learning how to learn is a crucial

and central component of all autonomous learning

schemes, displays progress, and evaluates individual

learning outcomes. This is shown in all the ten

students who were interviewed.

When the students were asked whether they

wanted to learn English out of classroom or

inside the classroom, all ten students gave positive

response that they preferred to learn out of the

classroom by using various methods like speaking

with friends, listening to English music, reading

English magazines, books and novels. They also

spent hours in doing so. (Richards, 2015) categorized

language learning into two dimensions: what goes

on inside the classroom and what goes on outside of

the classroom which seemed to be more interesting

from learners’ perspective. This study confirms

the findings from previous studies that provided

evidence that out-of-class study has a significant role

in language learning process and it can enhance

learners’ educational output in multiple ways (Fathali

and Okada, 2016); (Lai et al., 2011; Yoon, 2012)

and out-of-class learning is mainly influenced by

self-determined behaviours and self-regulated actions

(Mobarhan et al., 2014; Reinders, 2014).Gender has a

moderate effect on learner autonomy readiness.

The results showed that there was a significant

relationship between autonomous learning readiness

and English language performance. The results

proved that autonomous learning readiness

contributed significantly to the English language

performance. This is in line with the findings from

(Rienties et al., 2012). There is little empirical

research investigating whether Libyan students have

the propensity for autonomy. Hence this study

gives a comprehensive example of Libyan students

having readiness towards English language learning

autonomy.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study showed that students were

ready for autonomous learning. It is clear that

Libyan students have the propensity for autonomy

and their autonomy has a positive effect on their

English language performance. Through help,

ICoSEEH 2019 - The Second International Conference on Social, Economy, Education, and Humanity

114

understanding, guidance, support, and care of the

teacher, these students will be successful autonomous

language learners. However, since autonomy can be

incrementally developed by the teacher, students can

be gradually given full learning responsibility in the

hope that they will one day become fully autonomous.

Social collaborative learning amongst peers is the

most significant long-term motivational factor for

students to become involved with learning English

(Hughes et al., 2011). The results on the readiness

for learner autonomy and students’ performance

in English language can help EFL teachers to

be aware of readiness of learner autonomy of

students and improve their educational methods or

approaches in order to promote learner autonomy

and help students to work together collaboratively

and appreciate the value of autonomous learning with

more concentration since it will lead to learning

effectiveness.

Based on the findings on the readiness for

learner autonomy and students’ English language

performance, secondary schools’ administrators and

Libyan Ministry of Education could evaluate whether

autonomous learning is appropriate for the Libyan

learning framework and use the findings to strategize

further actions or implementations of autonomous

learning.

REFERENCES

Abukhattala, I. (2016). The use of technology in language

classrooms in libya. International Journal of Social

Science and Humanity, 6(4):262.

Aldabbus, S. (2008). An investigation into the impact of

language games on classroom interaction and pupil

learning in libyan efl primary classrooms.

Altaieb, S. (2013). Teachers’ perception of the

english language curriculum in libyan public schools:

An investigation and assessment of implementation

process of english curriculum in libyan public high

schools.

Benson, P., , and Voller, P. (2014). Autonomy and

independence in language learning. Routledge.

Benson, P. (2001a). Teaching and Researching Autonomy

in Language Learning. Pearson Education Limited

Education Limited, England.

Benson, P. P., editor (1997). Autonomy and independence

in language learning. Longman, London.

Benson, P. S. (2001b). Learner autonomy 7: Challenges to

research and practice.

Brown, H. (2007). Principles of Language Learning and

Teaching. Pearson Education Inc, New York.

Chan, V., Spratt, M., , and Humphreys, G. (2002).

Autonomous language learning: Hong kong tertiary

students’ attitudes and behaviours. Evaluation and

Research in Education, 16(1):1–18.

Creswell, J. (2013). Research design: Qualitative,

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage

publications.

Dam, L. (2011). Developing learner autonomy with school

kids: Principles, practices, results.

Dickinson, L. (1995). Autonomy and motivation a literature

review. System, 23(2):165–174.

Elmahjoub, A. (2014). An Ethnographic Investigation into

Teachers’ and Learners’ Perceptions and Practices in

Relation to Learner Autonomy in a Secondary School

in Libya. University of Sheffield.

Emhamed, E. and Krishnan, K. (2011). Investigating libyan

teachers’ attitude towards integrating technology

in teaching english in sebha secondary schools.

Academic Research International, 1(3):182.

Fathali, S. and Okada, T. (2016). On the importance

of out-of-class language learning environments: A

case of a web-based e-portfolio system enhancing

reading proficiency. International Journal on Studies

in English Language and Literature, 4(8):77–85.

Gardner, D., , and Miller, L. (1996). Tasks for Independent

Language. Learning: ERIC.

Hamilton, M. (2013). Autonomy and foreign language

learning in a virtual learning environment. AandC

Black.

Holec, H. (1981). Foreign Language Learning. Pergamon

Press, Oxford.

Hughes, L., Krug, N., , and Vye, S. (2011). Advising

practices: A survey of self-access learner motivations

and preferences. reading.

Ismail, N., Singh, D., , and Abu, R. (2013). Fostering

learner autonomy and academic writing interest

via the use of structured e-forum activities among

esl students. In Proceedings of EDULEARN 13

Proceedings, page 4622–4626.

Jha, S. (2015). Exploring desirable characteristics for libyan

elt practitioners. Journal of English Language and

Literature (JOELL), 2(1):78–87.

Krejcie, R. and Morgan, D. (1970). Determining

sample size for research activities. Educational and

Psychological Measurement, 30:607–610.

Lai, C., , and Gu, M. (2011). Self-regulated out-of-class

language learning with technology. Computer

Assisted Language Learning, 24(4):317–335.

Little, D. (1990). Autonomy in language learning. teaching

modern languages.

Little, D. (2007). Language learner autonomy: Some

fundamental considerations revisited. International

Journal of Innovation in Language Learning and

Teaching, 1(1):14–29.

Little, D. and Dam, L. (1998). Learner autonomy: What

and why? Language Teacher-Kyoto-Jalt-, 22:7–8.

Macaro, E. (1997). Target language, collaborative learning

and autonomy (vol. 5): Multilingual matters.

Mobarhan, R., Majidi, M., and Abdul Rahman, A.

(2014). Motivation in electronic portfolio usage for

higher education institutions. information systems and

Autonomous Learning Readiness and English Language Performance of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Libyan Secondary School

Students

115

technology for organizational agility, intelligence, and

resilience.

Orawiwatnakul, W. and Wichadee, S. (2017). An

investigation of undergraduate students’ beliefs about

autonomous language learning. International Journal

of Instruction, 10(1).

Palfreyman, D. and Smith, R. (2003). Learner autonomy

across cultures: Language education perspectives.

Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Reinders, H. (2014). Personal learning environments for

supporting out-of-class language learning. Paper

presented at the English Teaching Forum.

Richards, J. (2015). The changing face of language

learning: Learning beyond the classroom. RELC

Journal, 46(1):5–22.

Rienties, B., Giesbers, B., Tempelaar, D., Lygo-Baker, S.,

Segers, M., and Gijselaers, W. (2012). The role of

scaffolding and motivation in cscl. Computers and

Education, 59(3):893–906.

Rungwaraphong, P. (2012). Student readiness for

learner autonomy: Case study at a university in

thailand. Asian Journal on Education and Learning,

3(2):28–40.

Sakai, S. and Takagi, A. (2009). Relationship between

learner autonomy and english language proficiency

of japanese learners. The Journal of Asia TEFL,

6(3):297–325.

Sawani, F. (2009). Factors affecting english teaching and

its materials preparation in libya.

¨

Ust

¨

unl

¨

uo

˘

glu, E. (2009). Autonomy in language learning:

Do students take responsibility for their learning?

Journal of Theory & Practice in Education (JTPE),

5(2).

Yoon, T. (2012). Are you digitized? ways to provide

motivation for ells using digital storytelling.

International Journal of Research Studies in

Educational Technology, 2(1).

Zarei, A., , and Zarei, N. (2015). On the effect

of language proficiency on learners’ autonomy and

motivation. Journal of English Language and

Literature, 3(2):263–270.

ICoSEEH 2019 - The Second International Conference on Social, Economy, Education, and Humanity

116