The Existence of Batik in the Digital Era

Irfa’ina Rohana Salma and Edi Eskak

Center for Handicraft and Batik, Ministry of Industry, Jl. Kusumanegara No. 7, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: existence, batik, digital era

Abstract: Batik is a real example of Indonesian artwork whose existence is still superior in today's world of art talks.

The existence of batik has even been recognized by UNESCO on 2009 as one of the world's cultural intangible

heritages. Batik is understood as a whole process of creation, the work produced, and the philosophy. The

b

atik consensus, in the manufacturing process, was challenged by manual and machine printing, and now in

digital printing. The purpose of this paper is to examine the existence of original batik processed with

traditional technology that can still be sustainable and develop in this digital era. The method used is

descriptive qualitative to show the existence of batik in the digital era. The result is traditional batik in this

digital era is still exists. Counterfeiting batik products can be anticipated by labeling Batikmark "INDONESIA

b

atik". Digital technology can be used to support the research and other aspects related to batik. The role o

f

art, government, university, private sector, artists, and individual batik lovers also play an important

assignment in the preservation and development of traditional batik until this millennium.

1 INTRODUCTION

Indonesia has a rich diversity of arts, including batik

whose existence has been recognized worldwide. The

world recognition of batik by UNESCO on October

2, 2009, has aroused love for batik in wider society.

The love of batik as a culture belonging to Indonesia

has been able to revive a sense of nationalism. Batik

is no longer just a handicraft in a cloth decorated

beautifully as a clothing, but it has become an icon of

nationalism itself (Eskak & Salma, 2018).

Appreciating this, the government set a date of

October 2

nd

as a National Batik Day. The

determination of the National Batik Day is actually a

sign of the importance of strengthening and

developing batik as a proud national identity in

international forums

Batik in all techniques, technologies and

designs related to its motifs and cultures behind it, has

been recognized by UNESCO as Masterpieces of the

Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Traditional batik is created through a series of

physical and inner processes into a beautiful piece of

cloth full of philosophical meaning, so that batik

reflects the characteristics of the nation. Pride with

love using batik by the large community, helped

trigger the rise and development of batik industry

which had previously experienced a setback (Salma

& Eskak, 2016). This supports the existence of batik

while maintaining its sustainability. Existence comes

from the word existere, Latin which means to appear,

exist, arise, or have an actual existence. Existere

comes from the ex word which means out and sistere

which means to show or appear (Bagus, 1996). To

conserve and develop the traditional art is the youth

obligation so that the existance of batik will remain

awake (Eskak, 2013). The existence of batik remains

sustainable, always appears in the repertoire of art,

and actually still exists in society as an artwork and

industrial prosperity in today's digital era.

The digital era is a change time born with the

emergence of digital, internet networks, especially

computer information technology. The new media of

digital era has characteristics that can be manipulated

and online. The mass media is turning to the new

media or the internet because there is a cultural shift

in the delivery of information. This digital era's media

capabilities make it easier for people to receive

information faster (Setiawan, 2017). The use of

advanced digital technology is a necessity in

maintaining the existence of traditional arts, including

in batik. In this digital era, the art and culture space of

40

Salma, I. and Eskak, E.

The Existence of Batik in the Digital Era.

DOI: 10.5220/0008526000400049

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative Technology (CREATIVEARTS 2019), pages 40-49

ISBN: 978-989-758-430-5

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

the community changes as the development of

information technology and media (Kusrini, 2015).

Today's digital era with the development of

technology has greatly eroded old traditions in

society. Batik is one of the traditional arts affected by

the advancement of this technology. Original batik

has a big challenge from manual and masinal printing

technology, and by digital printing technology now.

Batik is falsified and marketed massively. Artificial

batik products flood the market when consumers have

not had the chance to understand between original

batik and its artificial. Many consumers are harmed

by counterfeiting this batik, due to a lack of

understanding of original batik, while the artificial

one has produced to try to imitate batik as closely as

possible with its original. This condition can turn off

the traditional batik industry. Creativity is good, but

if you aim to imitate for forgery it is certainly an act

of fraud (Eskak, 2014). Smart consumers will choose

original batik as a high appreciation for batik. Digital

information technology can also be used to support

the existence of original batik by spreading out

education about the differentiation of original or

artificial batik, so that consumers are not harmed.

Digital technology also allows to be used to support

the existence of batik through research and

development of both design, raw materials, marketing

methods, and so on according to times. The purpose

of this paper is to examine the existence of original

batik processed with traditional technology that can

still be sustainable and develop in this digital era.

2 METHODS

The method used is descriptive qualitative to explore,

analyze, and present data to show the existence of

batik in the digital era. Koentjaraningrat (1986)

explain that what is meant by descriptive is a picture

as accurately as possible about an individual,

condition, symptom or certain group. According to

Nazir (2013) descriptive method is a study to find

facts with the right interpretation. Data is obtained

from various sources, both from the study of

literature, documentation, etc., which are relevant and

support the research object. Data acquisition is then

analyzed qualitatively with interpretative that is

through several processes such as: data verification,

data reduction, data presentation, and conclusion.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results are knowing that the existence of batik in

this digital era is still sustainable and developing.

Original batik is still defined as an ornamental

artwork on cloth which is made using hot wax as a

color resist dyed with handwritten canting or stamp

canting of applying hot batik wax on mori. This is

reinforced by SNI 0239: 2014 of batik. Counterfeiting

batik products can be anticipated by labeling

Batikmark "INDONESIA batik". The digital era

technology in batik is used as a support in research

and development, and other aspects related to batik in

this digital era.

3.1 The Existence of Batik in Indonesia

Batik developed inside the palace walls at first, to

fulfill the clothing of the royal family and nobles. It

then developed out and became a people's industry to

produce clothing for the general public. Other than

Javanese’s, traditional batik also developed into

various regions including Sumatra batik, Kalimantan

Batik, Balinese batik, Nusa Tenggara batik, Sulawesi

batik, Maluku batik, and Papuan batik. The traditional

batik industry in clothing as well as a media of

cultural expression with local peculiarities of each

region at once.

Java is a place to grow and develop batik

which then spread throughout the archipelago, even

the world (Sukaya, Eskak, & Salma, 2018). Batik in

Java was originally an art within the palace walls

which aimed to make clothing material beautifully

decorated fabrics for the king and his family and

nobles. The decorations produced on batik cloth are

not just beautiful but have sacred symbolic meanings.

The history of batik in Java is closely related to the

development of the Ancient Mataram Kingdom

between the 9th and 10th centuries, continuing to the

12th century Kediri Kingdom, the 13th century

Majapahit Kingdom and beyond until now to the

Republic of Indonesia. Some experts suspect that

batik developed in Indonesia today originated from

Persia, China, India or Malay (Supriono, 2016). But

the skill of batik is actually found, developed, and

finally becomes a tradition from and by the

Indonesian people, both technologically and

philosophically. Batik motifs on Java are very diverse

with a long history of organic creativity, even the life

cycle of Javanese humans has had philosophical

guidance in a series of uses of batik motifs from birth-

married-married-adults-to death (Eskak & Salma,

2018). Javanese batik is growing rapidly in

The Existence of Batik in the Digital Era

41

Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Pekalongan, Cirebon, Lasem,

Tuban, Madura, and so on. Now the batik industry

can be found in almost all regions /cities throughout

Java. Javanese batik motifs include: Sekar Jagad,

Nitik Karawitan, Selampat Plate, Parang Buket

Tasikmalaya, Paksi Naga, Boketan Jakarta, Sido

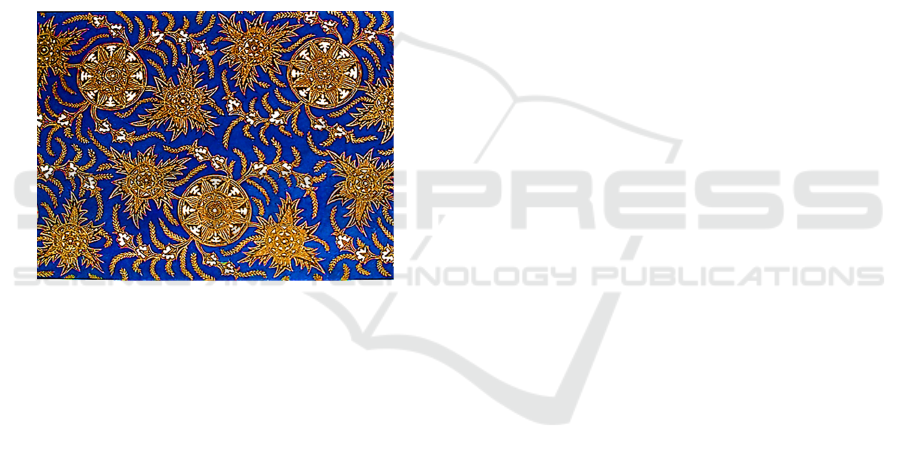

Mulyo, Surya Citra Majapahit (Figure 1), Ceplok

Kakao, etc. (Eskak & Salma, 2018). Some examples

of the existence of Javanese batik in journal studies

include: The Aesthetic Study of Sleman Batik Typical

Design: Semarak Salak (Salma & Eskak, 2012),

Aesthetic Study of Typical Batik Design in

Mojokerto: Surya Citra Majapahit (Salma, 2012b),

Ethnic Style and Dynamics of Batik Pekalongan

(Salma, 2013), Amri Yahya's Creative Batik in Levi-

Strauss's Structuralism Perspective (Salma, 2014a),

Coffee and Cocoa in Creative Jember Batik Motifs

(Salma, Wibowo, & Satria, 2015).

Figure 1: Motif Surya Citra Majapahit

(Salma, 2012a)

Although it is not as well-known as batik in

Java, this millennium batik in Sumatra shows a

growing trend. Its existence is also supported by the

existence of social media as a means of meeting,

sharing information and knowledge about the

development of batik technology, and as a means of

marketing. Sumatra Batik has actually developed

since the era of the kingdom, in Aceh around the 13th

century and in Minang the16th century (Supriono,

2016). Today batik in Sumatra develops in several

areas, among others: Aceh, Minang, Riau, Jambi,

Bengkulu, Palembang, and Lampung. Its existence

began to spread to regions such as batik Gayo ,

Darmasraya, Baturaja, Pringsewu, Bangka, Tanjung

Enim, and others. Sumatran batik motifs are very

diverse to each other, depicts local culture and nature.

For example, the existence of Aceh Gayo batik

developed a motif designed based on local carving

motifs which produced several motifs, namely: Gayo

Ceplok, Gayo Tegak, Gayo Lurus, Parang Gayo,

Gayo Lembut, and Geometris Gayo (Salma & Eskak,

2016). Baturaja Batik, South Sumatra also developed

regional motifs including motifs: Bungo Nan Indah,

Embun Nan Sejuk, Air Nan Segar, Kotak Nan

Rancak, and Ceplok Nan Elok (Salma, 2014b).

Kalimantan also has batik produced from the

hot wax technique resist. However, calling

Kalimantan batik is often confused with tritik

jumputan or sasirangan, even though technically and

the motifs are different (Eskak & Salma, 2018).

Kalimantan batik motifs, among others: Bayam Raja,

Naga Balimbur, Jajumputan, Turun Dayang, Daun

Jaruju, Kambang Tanjung, Batang Garing, Burung

Enggau, Mandau, Gumin Tambun, Kambang

Munduk, Dayak Latar Gringsing, and etc. In general,

Kalimantan batik motifs develop from typical Dayak

wood carving motifs, but there are also motifs those

are inspired by the flora and fauna of the local area,

as well as the cultural influences of immigrants.

Ketapang Batik in West Kalimantan for example, is a

Kalimantan batik with a background of Malay

culture. Dayak Latar Gringsing motif is a blend of

Dayak batik motifs with Javanese batik motifs. Also

developing Tidayu batik, this style is inspired by three

cultures at once, those are Dayak, Malay, and Chinese

which produce interesting motifs (Batik Kalimantan

Barat, 2018). Dayak batik motifs reflect the culture of

the Dayak people. Dayak term which means

"river"(Batik Kalimantan Timur, 2018). So this batik

illustrates various activities those are often related to

rivers. In general, Kalimantan batik has distinctive,

bold and colorful colors. Today batik is also

developing in Indonesia's youngest province, namely

North Kalimantan, its batik is known as Borneo

Batik. Borneo Batik has a variety of patterns and finer

motifs (Eskak & Salma, 2018). The existence of

Borneo batik enriches the cultural treasures of batik

from Kalimantan.

Sulawesi Island is thick with the tradition of

hand woven fabrics, but batik also developed in the

area. On this island batik developed in Tana Toraja,

Palu, Bantenan, Pinabetengan, and Minahasa

(Supriono, 2016). Sulawesi batik motifs are very

diverse based on the philosophy and socio-cultural

conditions of the community and the local natural

environment. Tana Toraja batik motifs include: Pare

Allo, Pa'teddong, Poya Mundudan. The typical colors

of Toraja batik are black, red, white and yellow. Batik

Tana Toraja continues to live and develop until now

(Supriono, 2016). Palu batik motifs include:

Sambulugana, Souraja, Burung Maleo, Bunga

Merayap, Bunga Cengkeh, Motif Ukir Kaili (Batik

Palu, 2013), Kaledo (Eskak & Salma, 2018), etc.

CREATIVEARTS 2019 - 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative

42

Minahasa batik motifs include: Tonaas Ang

Kayobaan, Tuama Loor, Turawesan Paredey,

Ma’sungkulan, Ma’suiyan, Wewengkalen, and etc.

(Supriono, 2016).

Bali Batik is a distribution of batik from Java.

Bali has great potential as a place to grow and develop

batik, because Balinese people are known to have

high intelligence in the arts. Batik in Bali is made for

various clothing needs in traditional ritual religious

ceremonies, as well as for everyday clothing, and also

to meet tourist needs as souvenirs (Supriono, 2016).

Balinese batik motifs are very diverse to others, apart

from having a rich traditional decoration, strong

creativity of artists, the tourism industry is also able

to absorb batik products quickly, so the dynamics of

creativity are quite fast and high. Bali's natural and

beautiful Balinese arts inspire artists to create works

of art (Yoga & Eskak, 2015), including Balinese batik

motifs. Balinese batik motifs are inspired by the

natural environment and culture of Bali and

influences from outside the region, which are

visualized as naturalist, decorative, and abstract

motifs. The combination of Balinese motifs with

Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Papua, and so

on, also occurs in Bali, because many immigrant

artists work in Bali (Eskak & Salma, 2018). The

Balinese batik motifs include: Jepun Alit, Jepun

Ageng, Sekar Jagad Bali, Teratai Banji, and Poleng

(Salma, Masiswo, Satria, & Wibowo, 2015).

Batik also developed in Nusa Tenggara, both

West and East. In West Nusa Tenggara there is a type

of Sasambo batik. This name is a combination of

three tribes inhabit West Nusa Tenggara, namely

Sasak (Lombok), Samawa (Sumbawa), and Mbojo

(Bima). These three tribes are united in building the

tradition of batik in West Nusa Tenggara (Supriono,

2016). Sasambo batik is done by using a technique of

attaching pieces of hot iron to the cloth to remove the

wax material that has been attached to the cloth first.

Sasambo batik motif that seems abstract is actually

interesting, it looks unique by creating its own

aesthetic that is different from other batik in general.

In addition to batik with the aforementioned

technique, batik in West Nusa Tenggara also

develops as in general, by applying hot batik wax

techniques using a canting as a tool. Uma Lengge

Batik is a typical Bima batik creation inspired by the

traditional Bima rice barn building. The Uma Lengge

Batik motif consists of the main Uma Lengge motif,

a filler motif in the form of rice strands and traditional

dance (Sartika, Eskak, & Sunarya, 2017), This motif

can be seen in Figure 2. Batik that developed in East

Nusa Tenggara is centered in Kupang. Kupang Batik

is a diversification of handwoven textile products

from the hand weaving tradition that has developed

earlier. The batik technique used by applying hot

batik wax techniques in general both with

handwritten canting or stamp canting and its

combination. Kupang batik motifs include: Rukun

Kupang, Teguh Bersatu, Pucuk Mekar, Liris Kupang,

Kuda Sepasang, and Kuda Kupang (Salma, Eskak, &

Wibowo, 2016).

Figure 2: Motif Uma Lengge

(Sartika, Eskak, & Sunarya, 2017)

Maluku also has batik or often referred to as

Maluku batik. Maluku Batik has a characteristic in

accordance with the cultural repertoire and the natural

wealth of the region itself. The distinctive

characteristics of Maluku batik are its motifs inspired

by the produce of its natural sources: Pala, Cengkih,

Peta Maluku, and Flora Fauna. In addition there are

Parang motifs, Salawaku, and Tifa Totobuang (Seni

Batik Maluku, 2018). Sawaluku is a typical of

Maluku weapon and totobuang is a type of

drum/percussion instrument. North Maluku also has

batik, named Tubo batik, taking the name itself from

a village in Ternate, the village where Ternate batik

was first made. Tubo Ternate residents initially made

batik since 2010 and after time it turned out that many

like this Tubo batik (Batik Khas Maluku, 2013). The

distinctive feature of Tubo-Ternate batik is almost the

same as Maluku batik (Eskak & Salma, 2018).

Batik also exists in Papua, initially Papuan

batik was influenced by the style of Pekalongan batik

because of business calculations were more profitable

that batik motifs from Papua were produced in

Pekalongan, then sent to Papua and traded as Papuan

batik. Papuan Batik began to develop around 1985,

the developing motif was a blend of two cultures

between Papua and Pekalongan. Papuan Batik has its

own uniqueness from its motif aspect, because it was

developed from the cultural richness and exotic

nature of Papua. Papuan Batik motifs include: Honai

Besar, Honai Kecil, Tifa Besar, Tifa Kecil, Tambal

The Existence of Batik in the Digital Era

43

Ukir Besar, and Tambal Ukir (Salma, Ristiani, &

Wibowo, 2017). The discussion above is an

illustration of the existence of batik in Indonesia in

this millennium. Of course there are still many batik

industries that have started to develop and cannot be

discussed in this paper.

3.2 The Existence of Traditional Batik

Batik is not a cultural result that lives only as

an artifacts, but as an culture itself lives and develops

in a real way in society. Recognition and appreciation

as a unique cultural heritage that is still alive and

passed down from generation to generation, provides

a sense of community identity, and is considered as

an effort to respect cultural diversity and human

creativity. Batik recognized by UNESCO is

traditional batik or its original, batik whose process

uses conventional batik standards that have been

standardized in SNI (Standar Nasional Indonesia)

0239:2014. Original batik which is the process is

making using hot wax as a color barrier material

(Salma, Wibowo, & Satria, 2015). Batik technique is

a work process from the beginning of the preparation

of mori to the batik cloth (Susanto, 2018). Batik wax

resist the color absorption in dyeing, so that there is a

contrast of colors that are reinforced by wax tunnel

lines, so a motif is created on the surface of the fabric.

SNI 0239:2014 about: Batik - Understanding and

Terms, namely batik is a handicraft as a result of color

resisting using hot batik wax as a color resist dyed

with hand written canting or stamping canting as the

main tools to apply hot batik wax to form certain

motifs that have meaning (BSN, 2014).

The higher people’s level of education,

appreciation of art and increase in income, the more

will be for people to return to traditional batik and buy

it, even though its price is more expensive than the

price of artificial batik textiles. There is a people’s

feeling of prestige decreasing when the cloth they

worn is not original batik but the imitation one. This

is also one of the pillars of the existence of traditional

batik. Traditional batik is created through a series of

physical and inner processes into a beautiful piece of

cloth full of philosophical meaning, so that batik

reflects the characteristics of the nation. Pride with

love using batik by the large community, helped

trigger the rise and development of batik industry

which had previously experienced a setback (Salma

& Eskak, 2016). This supports the existence of batik

while maintaining its sustainability. Existence comes

from the word existere, Latin which means to appear,

exist, arise, or have an actual existence. Existere

comes from the ex word which means out and sistere

which means to show or appear (Bagus, 1996). To

conserve and develop the traditional art is the youth

obligation so that the existance of batik will remain

awake (Eskak, 2013). The existence of batik remains

sustainable, always appears in the repertoire of art,

and actually still exists in society as an artwork and

industrial prosperity in today's digital era.

3.3 The Role of Higher Education and

Research and Development

Institutions

Today, when visiting various regions in

Indonesia, regional batik will be found, even though

the area is not known as the basis of the batik industry

tradition. The existence of batik throughout Indonesia

until now is thanks to the hard work of various parties,

both government and private sector related to batik,

both from the world of education, related agencies,

and Research and Development institutions. The

world of education includes vocational majoring in

textiles/batik (SMK 5 Yogyakarta, SMK 2 Jepara,

SMK Rota Bayat Klaten, and etc.), ISI Yogyakarta,

ISI Surakarta, ISI Denpasar, ISI Padangpanjang,

FSRD ITB, FBS UNY, Universitas Telkom Bandung,

and many more universities that have art/design

majors have taken a part. Related agencies include:

Department of Industry and Trade. Department of

Manpower, Department of Economy, Department of

Education and Culture, Plantation Service, and

others. The stakeholders include the National Craft

Council, the Indonesian Batik Foundation, Sekar

Jagad Association, Pertamina CSR, Mandiri CSR,

and others. As an example, the following is one of the

main role of the central government through the

Ministry of Industry with special craft and batik

Research and Development institutions namely

BBKB (Center for Handicafts and Batik). The growth

and development of the batik industry turned out to

have been sought by the government for a long time,

even when the Dutch East Indies government was in

1922 by establishing an institution "Textile Inrichting

En Batik Proefstation". This institution was later

better known as "Balai Batik". In the independence

era this institution was named the Batik Research

Center, because of the demands of a wider scope it

was developed into the Batik and Handicraft

Research Institute. In 1980 the Batik and Crafts

Research Center changed to the Center for Research

and Development of the Handicraft and Batik

Industry. In 2002 the institution changed its name

again to the Center for Handicraft and Batik (Wardi,

2018). The Center for Handiraft and Batik (BBKB) is

a government institution under the Ministry of

CREATIVEARTS 2019 - 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative

44

Industry which has the task of carrying out research,

development, cooperation, standardization, testing,

certification, calibration and development of the craft

and batik industry competencies (Trapsiladi, 2016).

BBKB is a government institution under the Ministry

of Industry which has the task of carrying out

research, development, cooperation, standardization,

testing, certification, calibration and industrial

competency development and craft. (Making

Indonesia 4.0 - Kementerian Perindustrian, 2016).

Research and Development activities carried out

by BBKB is to improve the competitiveness of batik

SMEs, one of which is the development of regional

batik motifs. One important aspect in batik products

is the design of decorative motifs (Sartika, Eskak, &

Sunarya, 2017). These activities in the last 5 years

were published in the journal dynamics of crafts and

batik (Dinamika Kerajinan dan Batik/DKB) motif

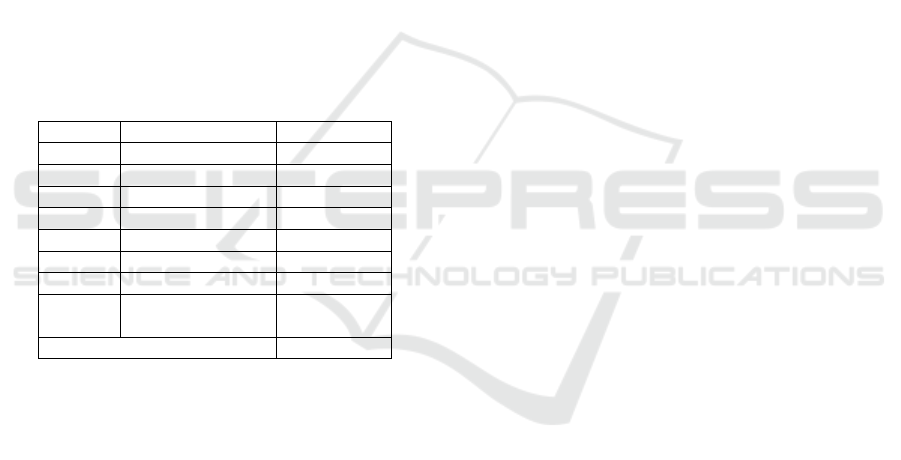

development was found in 7 regions. Table 1 shows

the development of the last 5 years motifs from 2013

to 2018 carried out by BBKB.

Table 1: Development of regional batik motifs

Years Region The Results

2013 Sumatera 10

2014 Baturaja 5

2014 Maluku 3

2015 Bali 5

2015 Jember 6

2016 Kupang 6

2017 Papua 6

2018 East Nusa

Tenggara

7

Total 48

In 2013 the development of a typical

Sumatran/Malay batik produced 10 motifs namely:

Ayam Berlaga, Bungo Matahari, Kuntum

Bersanding, Lancang Kuning, Encong Kerinci,

Durian Pecah, Bungo Bintang, Bungo Pauh Kecil,

Riang-Riang, and Bungo Nagaro (Murwati &

Masiswo, 2013). In 2014 the development of the

typical batik motif of Baturaja, South Sumatra

produced 5 distinctive Baturaja motifs, namely:

Bungo Nan Indah, Embun Nan Sejuk, Air Nan Segar,

Kotak Nan Rancak, and Ceplok Nan Elok (Salma,

2014). In this year, a typical Maluku motif batik was

carried out 3 motifs, namely: Siwa, Siwa Talang, and

Matahari Siwa Talang (Masiswo & Atika, 2014).

Batik motifs that developed in Bali also received

attention from BBKB, Balinese batik is considered

not to much reflect the distinctive identity of the

region, therefore it is necessary to create typical

Balinese batik motifs. The source of inspiration for

the creation of its motifs was explored from Balinese

culture and nature. This activity produces 5 batik

motifs that have typical Balinese characteristics,

namely: Jepun Alit, Jepun Ageng, Sekar Jagad Bali,

Teratai Banji and Poleng Biru (Salma, Masiswo,

Satria, & Wibowo, 2015). Batik Jember also gets

BBKB attention, Jember batik has been synonymous

with tobacco leaf motifs, but its visualization in batik

motifs lacks of character because the motif appears

like a picture of a leaf in general. Therefore BBKB

created a unique Jember motif whose source of

inspiration was explored from things that were more

characteristic of Jember. This activity succeeded in

creating 6 motifs namely: Uwoh Kopi, Godong Kopi,

Ceplok Kakao, Kakao Raja, Kakao Biru, and Wiji

(Salma, Wibowo, & Satria, 2015).

Development of regional batik motifs is also

done in Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara (NTT). BBKB

develops its motifs by drawing inspiration from

typical traditional weaving motifs of the local area.

This activity produces 6 motifs, namely: Rukun

Kupang, Teguh Bersatu, Pucuk Mekar, Liris Kupang,

Kuda Sepasang, and Kuda Kupang (Salma, Eskak, &

Wibowo, 2016). The development of the batik

industry in Papua has experienced various obstacles,

including stagnation in the making of motifs those are

oriented only to the mascot of the region, birds of

paradise. Therefore design diversification needs to be

done. Then BBKB develops motif designs with a

source of inspiration from the traditional tool of

Papuan community. Tools as the traditional devices

commonly used by Papuans when at home, while

working, fighting, and performing arts. This activity

produces 6 motifs, namely: Honai Besar, Honai

Kecil, Tifa Besar, Tifa Kecil, Tambal Ukir Besar,and

Tambal Ukir Kecil. (Salma, Ristiani, & Wibowo,

2017). BBKB also develops products by combining

between weaving techniques and batik techniques

which then produces new products with the acronym

"nuntik" which is a blend of weaving and batik. The

products produced are very unique and distinctive

theme. Thematic motifs for nuntik raised from the

East Nusa Tenggara's cultural arts. This activity

produces 7 motifs, namely: Jago, Gading, Gajah,

Kapas, Lontar, Tumpal, and Perhiasan (Salma,

Syabana, Satria, & Cristianto, 2018).

The direction of the development of the motif is

adjusted to the cultural peculiarities of the region, the

coastal area is certainly different from the

mountainous region. The direction of developing

Kupang motifs is certainly different from Baturaja

batik patterns. The development of batik in coastal

areas tends to produce patterns that are very varied,

The Existence of Batik in the Digital Era

45

the color is not limited to brown and blue but also

displays in red, green, light blue and yellow (Sutarya,

2014). Typical regional motifs those are created still

refer to the distinctiveness of the region both

traditional arts and local natural uniqueness, so that

new creatures are not uprooted from their cultural and

environmental roots. Typical regional motifs are batik

motifs those have unique visual elements and

characteristics, characterized certain regions. The

natural environment and the distinctiveness of

regional cultural arts can be used as inspiration for the

work of art that has economic value as a means of

advancing the welfare of society in the era of the

creative industry today (Yoga & Eskak, 2015). An

example in Figure 3 is a typical Jepara batik, Ceplok

Semi motif, developed from leaf motifs on Jepara

carvings.

Figure 3: Semi Ceplok motif of Jepara Batik

3.4 Artificial Batik Textiles Threaten the

Existence of Traditional Batik

Today's digital era of original batik has been

challenged by print technology. Batik was falsified

and marketed on a large scale. Artificial batik

products flood the market when consumers have not

had the chance to understand between original batik

and the imitiation one, and it is indicated that batik

counterfeiters are also imitating batik form as closely

as possible. Consumers are interested in buying

because the price is much cheaper. Impish batik

traders usually mix imitiation batik with the original

one, and sell it in original batik’s price to get a higher

profit. The producers of artificial batik textiles also

constantly improve technology and creativity trying

to make batik as closely as possible with original

batik. This condition can turn off the traditional batik

industry.

Artificial batik textiles or imitation batik is the

manufacture of batik motifs but not through the stages

of traditional batik processes or according to the 2014

SNI Batik, which uses hot wax as a resist-dyed to

make motifs. Batik counterfeiting is done in more

effective and efficient technique, by printing

technology both manually and masinally. It is

summarizing the process by skipping off hot wax as

a resist-dyed uses to make motifs done with

handwritten or stamp canting. There is also a screen

printing techniques combined with hot wax to make

motifs on some after-painted batik screen printed, so

that it can eliminate the smell of screen printing paint

and replace it with the smell of hot wax after-

removed. In order for consumers not to be deceived

in buying batik, they can recognize the characteristics

of printing batik, which only has one cloth surface of

batik sharp-pictured, while the other side of the

picture and color is not as perfect as the opposite one.

It is because of coloring process uses paste paint

printed from the one side of the cloth only. Another

characteristic is the decorative motif looks neat with

symmetrical repetition, because of the repetition

results of the equipment or machine prints.

Traditional batik consider as a hand made product

will looks less neat, but feels more supple. Other than

not to be fooled in an easier way, consumers can buy

batik cloth labeled of batikmark "INDONESIA

batik". The price of this labeled batik poducts is

indeed higher, but the authenticity of the product is

guaranteed. Batikmark is an initiative of the Ministry

of Industry in an effort to preserve and develop

traditional batik products in Indonesia, as well as to

protect consumers from counterfeiting or misbuying

the imitation batik products.

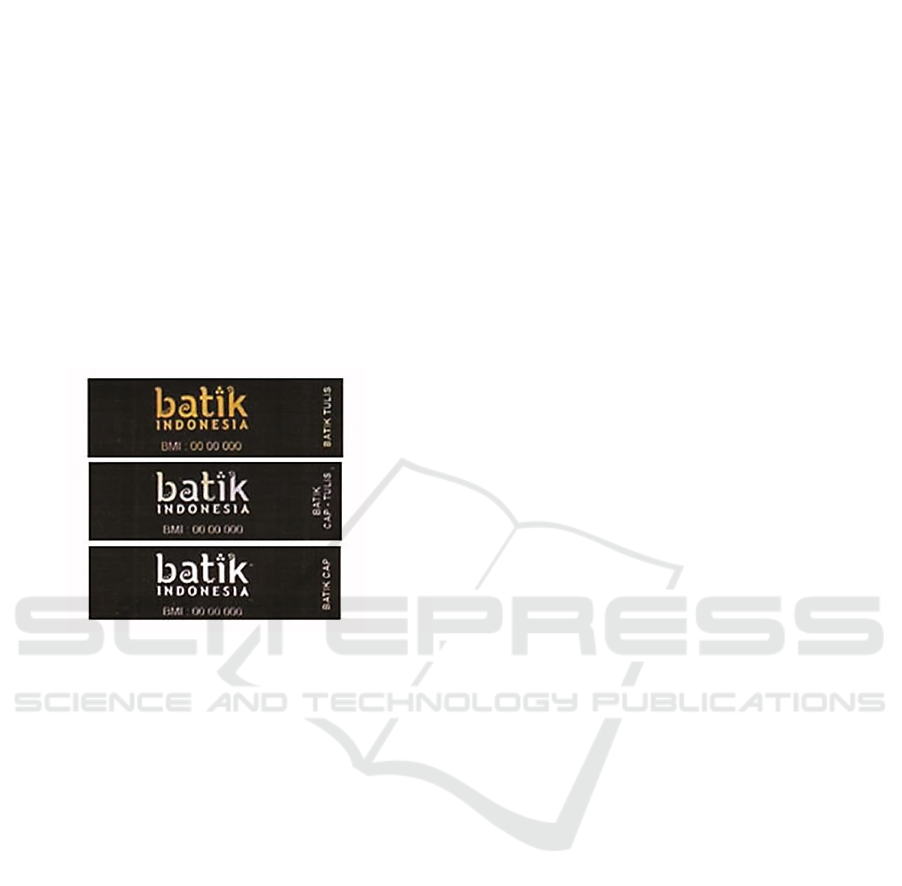

3.5 Batikmark “batik INDONESIA”

In an effort to preserve and develop batik

products in Indonesia, as well as protect consumers

from counterfeiting/imitation batik products, a

labeling policy of batik or Batikmark was made. The

theme of "Indonesian batik" hereinafter referred to

Batikmark is a label that shows the identity and

characteristics of Indonesian-made batik which

consists of three types, namely handwritten batik,

stamped batik and handwritten with stamped

combination batik with Copyright Number 034100 in

2007 (Figure 4). The text is used to label batik cloth

products original only, with curatorial and

administration done by the Center for Crafts and

Batik.

The purpose and benefits of Batikmark

labeling are based on the Minister of Industry

Regulation No.74/M-IND /PER /9/2007 concerning

"Use of Indonesian Batik" in Indonesian Batik ", the

use of Batikmark aims to: (1) Provide Indonesian

batik quality assurance ; (2) Increasing domestic and

CREATIVEARTS 2019 - 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative

46

foreign consumer confidence in the quality of

Indonesian batik; (3) To preserve and protect

Indonesian batik products legally from various threats

in the field of IPR and domestic and international

trade; (4) Giving Indonesian batik identity so that

local and foreign communities can easily recognize

Indonesian batik products (Nugroho, 2017).

The Batikmark logo is a distinguishing tool

made by Indonesian batik with batik products from

other countries, making it easier for foreign

consumers to know Indonesian batik or domestic

buyers to be more confident of what will be used as

genuine batik. The batiks that are installed in each

original batik product can minimize counterfeiting of

batik products (Prakosa, 2013).

Figure 4: Batikmark logo

4 CLOSING

4.1 Conclusion

Batik is not just a motif attached to the fabric, but an

entire process of creation, work produced, and

philosophy. Original batik was challenged by the

development of artificial batik produced with manual

and masinal printing technology, and now digital

printing. Imitation products of batik are now flooding

the market. Despite the big challenges, the existence

of original batik in this digital era is still sustainable,

growing, and developing. Original batik made using

hot batik wax as a color resist dyed with the main

tools of hand written canting or stamp canting. The

existence of batik today is thanks to the support of

various parties, those are batik consumers, batik

lovers, batik artists, batik industry communities, batik

associations, related agencies, educational

institutions, Research and Development institutions,

and millennials who love batik. The Batikmark label

"batik INDONESIA" can also support the existence

of original batik. Today's digital technology is used to

support the existence of batik through research and

revelopment, and other aspects related to the batik

industry

4.2 Suggestions

One type of batik, batik painting that once triumphed

in the 1980s, needs to be revived, and to be supported

by relevant Research and Development. Regulation

of artificial batik needs to be emphasized by giving

legal sanctions and labeling, so that the existence of

original batik can be maintained and consumers are

not harmed. Digital technology is further explored to

maintain the existence of original batik, for example,

the innovation of the scanner for the authenticity of

batik products, natural color batik scanners, and so

on. Batikmark is more actively socialized so that

more batik industries use it. Competition such as

"canting emas UNY", design competition, fashion

competition, need to be livened up again so that the

existence of batik is increasingly felt in the midst of

society.

REFERENCES

Bagus, L., 1996. Kamus Filsafat. Jakarta: Gramedia.

Batik Kalimantan Barat. Retrieved August 23, 2018,

from https://infobatik.id/batik-kalimantan-

barat

Batik Kalimantan Timur., 2018. Retrieved August 23,

2018, from https://infobatik.id/batik-

kalimantan-timur

Batik Khas Maluku., 2013. Retrieved August 24,

2018, from

https://fitinline.com/article/read/batik-khas-

maluku/

Batik Palu, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2018, from

https://fitinline.com/article/read/batik-palu/

Eskak, E., & Salma, I. R., 2018. Menggali Nilai-nilai

Solidaritas Dalam Motif Batik Indonesia.

Jantra, 13(2), 11–28.

Eskak, E., 2013. Mendorong Kreativitas Dan Cinta

Batik Pada Generasi Muda Kritik Seni Karya

Pemenang Lomba Desain Batik Bbkb 2012.

Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 30(1), 1–10.

https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.22322/dkb.

v30i1

Eskak, E., 2013. Metode Pembangkitan Ide Kreatif

Dalam Penciptaan Seni. Corak, 2(2), 167–174.

https://doi.org/DOI: 10.24821/corak.v2i2.2338

Koentjaraningrat, 1986. Pengantar Ilmu Antropologi.

Jakarta: Aksara Baru.

Kusrini, 2015. Potret Diri Digital dalam Seni dan

The Existence of Batik in the Digital Era

47

Budaya Visual. Journal of Urban Society’s

Arts, 2(2), 2(2111–122.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24821.

Making Indonesia 4.0 - Kementerian Perindustrian,

2016. Retrieved February 20, 2019, from

www.kemenperin.go.id/download/18384

Masiswo dan Atika, V., 2014. Aplikasi Ornamen

Khas Maluku Untuk Pengembangan Desain

Motif Batik. Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik,

3(1), 22–30.

Murwati, E. S. dan M., 2013. Rekayasa

Pengembangan Desain Motif Batik Khas

Melayu. Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 30(2),

67–72.

Nazir, M., 2013. Metode Penelitian. Bogor: Ghalia

Indonesia.

Nugroho, H., 2017. Labelisasi Batikmark “batik

INDONESIA.” Retrieved December 17, 2018,

from

https://bbkb.kemenperin.go.id/post/read/labelis

asi_batikmark____batik_indonesia____0

Prakosa, G., 2013. Batikmark, Upaya Untuk

Lindungi Batik Indonesia. Jakarta. Retrieved

from

https://ekbis.sindonews.com/read/741140/34/b

atikmark-upaya-untuk-lindungi-batik-

indonesia-1366708518

Salma, I. R., & Eskak, E., 2012. Kajian Estetika

Desain Batik Khas Sleman Semarak Salak.

Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 32(2), 1–8.

Salma, I. R., & Eskak, E., 2016. Ukiran Kerawang

Aceh Gayo Sebagai Inspirasi Penciptaan Motif

Batik Khas Aceh Gayo. Dinamika Kerajinan

Dan Batik, 33(2), 121–132.

Salma, I. R., Eskak, E., dan Wibowo, A. A., 2016.

Kreasi Batik Kupang. Dinamika Kerajinan Dan

Batik, 33(1), 45–54.

Salma, I. R., Masiswo., Satria, Y., dan Wibowo, A.

A., 2015. Pengembangan Motif Batik Khas

Bali. Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 32(1),

23–30.

Salma, I. R., Ristiani, S., dan Wibowo, A. A., 2017.

Piranti Tradisi Dalam Kreasi Batik Papua.

Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 34(2), 63–72.

Salma, I. R., Syabana, D. K., Satria, Y., dan

Cristianto, R., 2018. Diversifikasi Produk

Tenun Ikat Nusa Tenggara Timur Dengan

Paduan Teknik Tenun Dan Teknik Batik.

Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 35(2), 85–94.

Salma, I. R., Wibowo, A. A., & Satria, Y., 2015. Kopi

Dan Kakao Dalam Kreasi Motif Batik Khas

Jember. Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 32(2),

63–72.

Salma, I. R., 2012a. Kajian Estetika Desain Batik

Khas Mojokerto “Surya Citra Majapahit.”

Ornamen, 9(2), 123–135.

Salma, I. R., 2012b. Kajian Estetika Karya Batik

Khas Mojokerto: Surya Citra Majapahit.

Ornamen, Jurnal Kriya Seni ISI Surakarta,

9(2), 123–135.

Salma, I. R., 2013. Corak Etnik Dan Dinamika Batik

Pekalongan.

Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik,

30(2), 85–97.

https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.22322/dkb.

v30i2.1113.g946

Salma, I. R., 2014a. Batik Kreatif Amri Yahya Dalam

Perspektif Strukturalisme Levi-Strauss.

Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 31(1), 41–52.

https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.22322/dkb.

v31i1.1060.g902

Salma, I. R., 2014b. Seni Ukir Tradisional Sebagai

Sumber Inspirasi Penciptaan Batik Khas

Baturaja. Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik,

31(2), 75–83.

https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.22322/dkb.

v31i2.1070

Sartika, D., Eskak, E., dan Sunarya, I. K., 2017. Uma

Lengge Dalam Kreasi Batik Bima. Dinamika

Kerajinan Dan Batik, 34(2), 73–82.

Seni Batik Maluku., 2018. Retrieved August 24,

2018, from https://infobatik.id/seni-batik-

maluku/

Setiawan, W., 2017. Era Digital dan Tantangannya.

In PROSIDING Seminar Nasional Pendidikan

2017: Pendidikan Karakter Berbasis Kearifan

Lokal untuk Menghadapi Isu-isu Strategis

Terkini di Era Digital (pp. 1–9). Sukabumi:

Universitas Muhammadiyah Sukabumi.

Retrieved from

file:///C:/Users/user/SkyDrive/Documents/1.

Era Digital dan Tantangannya.pdf

SNI 0239. Batik – Pengertian dan Istilah, 2014.

Republik Indonesia: Badan Standardisasi

Nasional.

Sukaya, Y., Eskak, E., dan Salma, I. R., 2018.

Penambahan Nilai Guna Pada Kreasi Baru

Produk Boneka Batik Kayu Krebet Bantul.

Dinamika Kerajinan Dan Batik, 35(1), 15–24.

Supriono, P., 2016. The Heritage Of Batik: Identitas

Pemersatu Kebanggaan Bangsa. Yogyakarta:

Penerbit Andi.

Susanto, S. K. S., 2018. Seni Kerajinan Batik

Indonesia. (Tim Ahli BBKB, Ed.). Yogyakarta:

Penerbit ANDI.

Sutarya., 2014. Eksistensi Batik Jepara. Disprotek,

5(1), 19–33.

Trapsiladi, P., 2016. Tugas Pokok dan Fungsi Balai

Besar Kerajinan dan Batik. Retrieved January

CREATIVEARTS 2019 - 1st International Conference on Intermedia Arts and Creative

48

11, 2019, from

https://bbkb.kemenperin.go.id/page/show/tuga

s_pokok_dan_fungsi_0#

Wardi, 2018. Sejarah Balai Besar Kerajinan dan

Batik. Retrieved January 11, 2019, from

https://bbkb.kemenperin.go.id/page/show/sejar

ah_0

Yoga, W. B. S., & Eskak, E., 2015. Ukiran Bali

Dalam Kreasi Gitar Elektrik. Dinamika

Kerajinan Dan Batik, 32(2), 117–126.

https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.22322/dkb.

v32i2.1367.g1156

The Existence of Batik in the Digital Era

49