Collaborative Knowledge Management in University Alliances with

Information Models

Claudia Doering

a

and Christian Seel

b

Institute for Project Management and Information Modeling, University of Applied Sciences, Landshut, Germany

Keywords: Third Mission, Knowledge Management, Knowledge Transfer, Reference Modeling, Framework,

Information Modeling.

Abstract: Alliances between enterprises, such as Star Alliance, are a well-known phenomenon and have been subject

of research for the last decades. Today, universities are also beginning to form alliances among themselves.

Especially in the area of knowledge transfer alliances matter, as they create synergies, increase the visibility

and allow universities to carry out projects that cannot be done by a single university. However, a University

alliance creates new processes and interfaces between the member Universities. The management of such an

alliance is a knowledge management challenge on its own. Therefore, this paper gathers the requirements on

a University alliance and outlines how the business processes, that are specific for a University alliance, can

be structured in a framework. The framework indicates which processes are important for an alliance and on

which level they have to be addressed, on the level of a single University, first at each University and

afterwards in the alliance or on alliance level only.

1 INTRODUCTION

Besides the mission to teach and to conduct research,

a third mission in form of knowledge transfer

between universities, companies and society is

gaining increasingly importance (Roessler Isabel,

Duong Sindy, Hachmeister Cort-Denis, 2015). The

changes in the last thirty years in the environment of

universities show strong tendencies towards a greater

focus on activities in collaboration with society

(Roessler Isabel, Duong Sindy, Hachmeister Cort-

Denis, 2015). Since at least the eighties, theoretical

frameworks around this topic where created, e.g. the

concept of “entrepreneurial universities” (Clark,

1998), ‘Triple Helix’ (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff,

2000) and “Mode 2” (Gibbons, 1994). What these

frameworks have in common is, that universities are

no longer seen as “ivory towers”, in which research is

cut off from society, but rather as institutions with a

deeper knowledge transfer. This engagement refers

not only to collaborations with the economy, but

includes also all forms of interactions with society

(Roessler Isabel, Duong Sindy, Hachmeister Cort-

Denis, 2015). In Germany, even the Framework Act

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3727-8773

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1538-0152

for Higher Education, defines knowledge and

technology transfer explicitly in § 2 as the third

mission of universities (Wissenschaftsrat, 2016).

This change has led to an even more competitive

environment for universities of applied sciences. This

arose mainly from the fact that universities are

competing against each other for funding, students

and projects. The competitive situation enhances with

an increasing geographic proximity between the

universities (Sturm and Spenner, 2018). This

situation can be described as ‘Coopetition’, in which

universities are at the same time competing and

cooperating with each other (Bouncken et al., 2015).

This phenomenon was first described in the context

of company alliances, to i.a. reduce R&D expenses

and to gain a broader market share (Hamel, Prahalad

and Doz, 1989). As universities are now establishing

alliances, a framework for these collaborations needs

to be consolidated, because universities face different

internal and external conditions than companies. The

reasons for cooperation in alliances vary and can

bring multiple advantages for all involved parties,

from which four points are outlined below: The first

is the possibility to deal with complex topics and an

increasing visibility through a common appearance

Doering, C. and Seel, C.

Collaborative Knowledge Management in University Alliances with Information Models.

DOI: 10.5220/0008346702430249

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2019), pages 243-249

ISBN: 978-989-758-382-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

243

(1). In this way, projects can be carried out or

concerns can be dealt with, which otherwise would

not be possible to be handled by individual

universities, as they are not able to cover every topic

in research. This is also due to the fact, that

universities of applied sciences are often smaller in

size and have less research focuses and fewer

resources than universities. So far universities of

applied sciences were perceived as local ‘knowledge

transfer providers’ (2), who can provide insights

through e.g. transfer of personnel or theses from

students with companies (Fritsch, Pasternack and

Titze, 2015). As the competition is now changing

from being local to a more global perspective, the

establishment of alliances can help to gain broader

global visibility (3) (Powell, Baker and Fernandez,

2017). Due to the fact, that universities are now also

competing against consulting firms for e.g.

governmental funding, they are building up alliances

with other universities of applied sciences (4)

(Jacobson, Butterill and Goering, 2004). We can see,

as a conclusion, that alliances provide a greater

impact and visibility. Also cost savings arise through

synergy effects in cooperations.

To facilitate the work in university alliances,

structural and organizational changes in the single

universities are needed. This would lead from a state

in which transfer is dependent upon the motivation of

single researchers to a state in which the whole

university would commit to it. Until now, research

has mainly focused on knowledge transfer from or to

individual universities and not on model based

knowledge transfer within and out of university

alliances. However, these differ significantly from

individual universities and need a greater support

through coordination and harmonization. In order to

visualize these circumstances, consistent processes,

organizational forms and harmonized documents are

needed, which will be defined in this article in a

business process information model. This framework

for knowledge transfer in university alliances will

ensure the sustainability of research and its results.

Therefore, the following research questions arise:

RQ 1 What are the specific requirements on

knowledge transfer in university alliances?

RQ 2 How can the processes of knowledge

transfer in university alliances be presented in a

structured framework?

The goal is to enable knowledge transfer within

university alliances, in order to allow for transfer with

companies or other protagonists.

This article is divided in the following sections: at

first the relevant research methodology is outlined.

Basic principles are then presented in the related work

section. RQ1 is answered in the section Requirements

on University Alliances. The next section covers RQ2

and demonstrates the framework for knowledge

transfer in university alliances. An evaluation of the

results completes this contribution.

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The chosen research questions and the research aim

guide the selection of the research methodology. A

research methodology must be defined for every

single research project and is derived from the

research questions (Seel, 2010). Because of its

research questions this paper follows the design

science research paradigm proposed by HEVNER et

al., as this research focuses on the creation of new

methods and artifacts (Hevner and Chatterjee, 2010).

The seven guidelines for Design Science in

Information Systems Research are implemented in

the following ways:

1. Design as an Artifact: as a result of the design-

science process an information model for

knowledge management in university alliances is

created.

2. Problem Relevance: The identified gap in

research and the current problem statement

display the relevance of the problem.

3. Design Evaluation: to ensure that the information

model and the shown processes display the

reality of collaborative knowledge management

adequately, expert surveys were carried out.

4. Research Contributions: Due to the identified

research gap, the information model represents a

contribution to the research.

5. Research Rigor: The creation of the information

model according to MEISE ensures the rigor of

research (Meise, 2001).

6. Design as a Search Process: The iterative search

process will be ensured through the comparison

of the deductive and inductive research findings.

7. Communication of Research: The purpose of this

article is to publish the research results and thus

to communicate them to the target audience via a

conference.

3 RELATED WORK

Knowledge Transfer is traditionally defined as an

interface between science and economy (Froese,

2014). Today, knowledge transfer describes all forms

of communication between an expert and a layperson

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

244

(Pircher, 2014). THIEL goes even further and defines

knowledge transfer as a targeted transfer of

knowledge from one transfer partner (sender) to

another transfer partner (receiver), whereby the

transfer partners can be individuals or collectives

(Thiel, 2002).

Nowadays, various definitions constitute third

mission and transfer as synonyms see e.g. (Henke,

Pasternack and Schmid, 2017; Noelting et al., 2018).

Although transfer has been incorporated in

universities for quite a long time, universities were

still defined as teaching and research-based

institutions and have therefore incorporated

organizational barriers which restrain the transfer of

knowledge. Several authors documented a lack of

administrative support concerning even basic aspects

of knowledge transfer e.g. creating contracts, support

concerning legal aspects or the supply of resources

etc. (Jacobson, Butterill and Goering, 2004). The shift

from teaching and research-based institutions to

universities which engage in the third mission, comes

along with the expectation, that university-based

researchers should engage under third mission

conditions, while the infrastructure at the universities

continues to consist of former conditions (Vorley and

Nelles, 2008).

Various authors have already described

knowledge transfer between organizations, see e.g.

HOFFMANN, who constitutes a framework for

intraorganizational knowledge transfer between

companies (Hoffmann, 2009). RAUTER, for example,

illustrates main contents of knowledge transfer

between companies and research institutes, without

giving model based recommendations (Rauter, 2013).

An existing model for knowledge transfer between a

specific discipline in universities and companies

describes exemplarily the procedure for knowledge

transfer, without giving general and evaluated

recommendations (Seel and Dreifuß, 2014).

Nevertheless, there is still no widespread, accepted,

and tested model based framework for knowledge

transfer between companies and university alliances.

4 REQUIREMENTS ON

UNIVERSITY ALLIANCES

Due to the emergence of university alliances the

system boundaries between single universities and

their environment were softened. This phenomenon is

comparable to the creation of the European Union.

The merging of individual countries to form the

European Union softened the national borders of the

member states and has shifted the previous system

boundary (Bux, 2008). By considering the system of

universities and their environment, it is noticeable

that the system boundary between individual

universities and their environment is equally softened

by the emergence of alliances. Between a single

university and its environment, one can now note the

alliance. According to the system theory by ROPOHL,

one can notice this change due to the emergence of

alliances (Ropohl and Lenk, 1978). Furthermore, a

new form of cooperation arises from the emergence

of alliances. Universities are now cooperating both

internally with each other and externally in form of

alliances with companies or social protagonists. From

this form of cooperation special requirements can be

derived (cf. RQ 1):

Req.1: A framework should shape the general

procedures, but must also allow for the single

universities to carry on their own processes.

Req.2: It should be possible to identify processes,

which are labelled differently in the single

universities in the alliance, to simplify the

collaboration and identify interfaces.

Req.3: Processes, which are heterogeneous should be

harmonized within the alliance.

Req.4: It must be recognizable which documents are

needed in the defined processes and the contents

which these documents need to contain.

Req.5: The framework must be easily understandable

and applicable for future users, to enable the

possibility to restructure own processes. Working in

alliances can bring structural influences to the

structure of the single universities. As collaborations

come along with sharing information and granting

access to resources facilities and funding, it is

necessary to transparently display the responsibilities

and accountabilities in each institution to effectively

collaborate. Since the organizational structure of the

collaborating universities tends to diverge strongly

from each other, it can be challenging to find the right

contact person or division in a collaborating

university. To enable these processes and the transfer

of knowledge a structured framework is needed. The

framework will guarantee to bring together all needed

persons and division and ensure comprehensive

knowledge transfer.

5 FRAMEWORK FOR

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER IN

UNIVERSITY ALLIANCES

According to HOLSAPPLE and JOSHI, knowledge

management models can be divided into the groups

Collaborative Knowledge Management in University Alliances with Information Models

245

of descriptive and prescriptive models (Holsapple and

Joshi, 1999).

Descriptive models try to cover and describe the

characteristics of knowledge management, whereas

prescriptive models define the elements and methods

and hence model knowledge management. This

research will go further than just analysing the current

status. As it intends to shape the target state of

knowledge transfer in university collaborations, it can

be described as a prescriptive model.

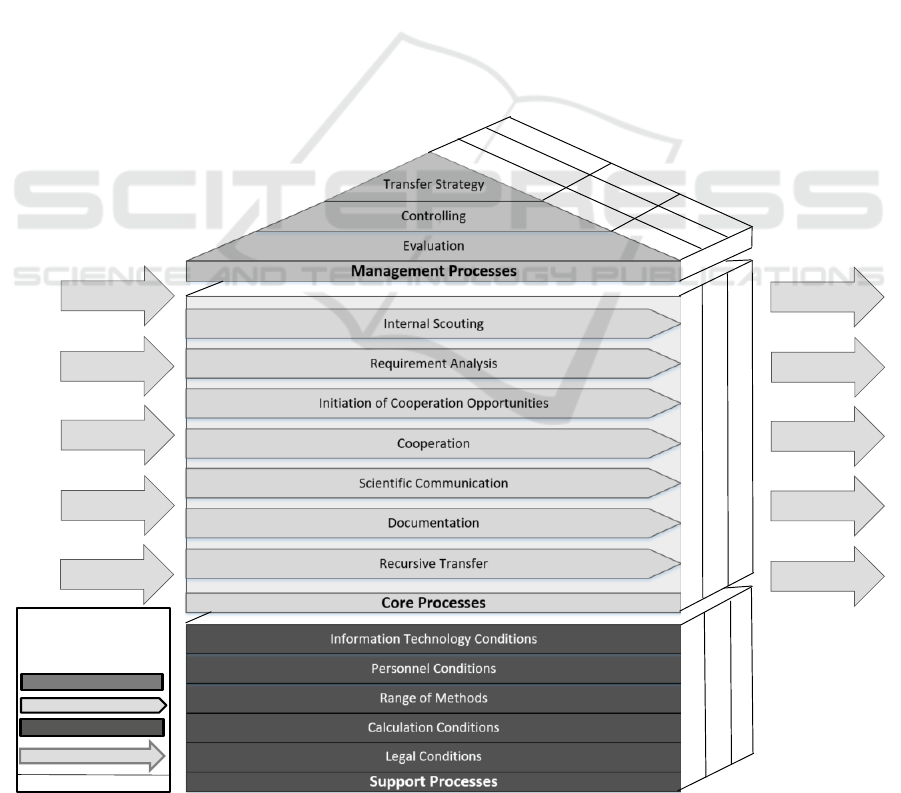

Due to the high complexity of knowledge transfer

in university collaborations, the information model

shown in figure 1 (cf. RQ 2) was created according

to the proposed structure by MEISE (Meise, 2001).

This information model, represents an artifact of the

Design Science process. The intended purpose of the

information model is to enable knowledge transfer in

university collaborations. According to MEISE, the

intended purpose of a regulatory framework is to

represent the elements and relations of subordinate

levels (Meise, 2001). Nevertheless, the intended

purpose is more than just a representation of

processes, the framework intends to establish

transparency and creates a common understanding of

all needed processes to enable knowledge transfer

within university alliances.

The structural design is based on the reference

design of a house. The level of agreement of this

representation facilitates the interpretation by the

target groups. These are primarily internal target

groups within the collaborating universities, e.g.

technology and knowledge transfer offices, research

and administrative departments and researchers. The

arrangement in management, core and support

processes in the roof, body and foundation of the

‘house’ creates a memorable image, which is of great

importance as the design of a framework contributes

decisively to the understanding of the structure

described by it (Meise, 2001). The framework for

knowledge transfer in university alliances consist of

two structural dimensions, the specification-content

and the specification-view (processes, organization,

documents). The specification-content outlines the

individual processes of knowledge transfer across

higher educational institutions. Three different types of

Figure 1: Framework for Knowledge Transfer in University Alliances.

I: Single University

II: First single, than

collaborative

III: Collaborative

Support Processes

Management Processes

Environmental Factors

Research

Institutes

Social

Protagonists

Companies

Legend

Processes

Organisation

Documents

II

II

II

III

III

II

II

III

II

I

II

II

III

II

II

Core Processes

Research

Institutes

Social

Protagonists

Companies

Researchers

Partners

Partners

Researchers

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

246

processes can be distinguished there:

I. Processes, which are solely carried out by single

universities.

II. Processes, which are first carried out by single

universities and then collaborative in the university

alliance.

III. Processes, which are solely carried out by the

university alliance.

Examples for this classification are: In a university

alliance each individual university will conduct a

recursive transfer process from research to teaching (I).

The transfer activities therefore shape the teaching

contents of the single researchers. The controlling of

all activities and projects will first be carried out by all

single universities and then brought together into

collaborative controlling (II). In this way, every

university can conduct its own controlling procedures,

but it contributes also to the controlling of the alliance.

An example for processes, which are solely carried out

by the university alliance, is the use of a common range

of methods (III). These consist of a range of

competences, which are intended to support transfer

activities (e.g. problem-solving or modeling

techniques) in the alliance. These methods are

available for all collaborating universities.

In contrast to other reference models,

recommendations for the organizational design can be

given, since in Germany basic features of the

organizational design of universities are predetermined

(see e.g. the Bavarian Higher Education Act

(BayHSchG, 2006)).

The document view shows the flow of relevant

documents in a university alliance. Thus

recommendations on which documents should be

created or used in relevant processes can be given.

Modeling the document view is especially important in

university alliances, as all processes require precise

and harmonised specifications. This also supports the

existing infrastructure in its change to the conditions

associated with the third mission.

In addition, the information model consists of

several levels of details, which describe the essential

core processes and functionalities of the transfer

processes. The information model (level 0) serves as a

mean to structure all subordinate processes. The core

processes (level 1) describe via value chain diagrams

the control and data flow (level 2) of the required

processes, which are modeled in detail in BPMN 2.0

and described in greater detail in process descriptions,

to simplify user understanding.

The representation of the processes in value chains

is suitable since in these processes, analogous to e.g.

producing companies, the value, hence the knowledge,

is created. The core processes are thus in the centre of

the information model and enable the alignment of all

processes towards value creation.

The environment of the framework is described by the

stakeholders ‘researchers’, ‘research institutes’, ‘social

protagonists’, ‘companies’ and ‘partners’. They can

collaborate with the university alliance through the

framework and use the proposed structures to e.g.

pursue research or commercial projects.

6 EVALUATION OF

REQUIREMENTS

The design science process aims to create artifacts to

solve practical problems (Hevner and Chatterjee,

2010). The evaluation of the key findings is one of the

core activities of the Design Science Process and aims

to prove and justify the artifacts. In order to prove the

usefulness of the chosen requirements, expert

interviews, in the context of a transfer project, were

conducted. These interdisciplinary expert interviews

were carried out in the context of a transfer project with

two universities and four universities of applied

sciences in Bavaria, Germany. These universities have

joint together to a university alliance in January 2018.

The experts had different backgrounds and experiences

with transfer projects, as they came from different

positions within the universities and universities of

applied sciences. Chosen experts are employees in

technology and knowledge transfer offices, research

funding departments, finance and legal departments

and researchers, who conduct research in collaborative

projects. All experts were chosen due to their

responsibility and experience in cross-organizational

knowledge transfer and their possession of privileged

information (Meuser and Nagel, 2009). Through the

expert interviews, comprehensive insights in

knowledge transfer could be acquired. The intention

was to ensure that the information model and the

shown processes display the reality of collaborative

knowledge management adequately. Thereby all

requirements were evaluated. The key findings of these

interviews are as follows.

A first indicator for the correctness of the

requirements is that the framework provides a general

overview and provides harmonized procedures of all

needed processes, but allows adjustment at the same

time (Req.1). All single universities in an alliance can

decide whether they want to take over all harmonized

processes or just parts of them. With giving generally

understandable labels of the processes, it is possible

that all universities in an alliance are able to identify

themselves in the framework, even if they label their

Collaborative Knowledge Management in University Alliances with Information Models

247

own processes differently (Req.2). An example is that

the process ‘Scientific Communication’, is also

labelled as ‘Press and Media’ or even ‘Marketing’ in

the single universities of the alliance, but the general

label in the framework clarifies the meaning easily.

This ensures the simplification of the collaboration and

helps to identify interfaces, connecting factors and

colleagues in other universities in the alliance. As the

organizational structures of the single universities in

the alliance diverge immensely, it can be hard to

identify corresponding organizational units or

processes in other universities in the alliance. General

understandable labels and the matching of business

processes and organizational units within the

framework support and facilitate the collaboration and

the knowledge transfer. The documented lack of

administrative support concerning even basic aspects

of knowledge transfer is currently a status quo at most

universities of applied sciences (Jacobson, Butterill

and Goering, 2004). Processes and documents, which

can be difficult to pursue or acquire can be delivered

and supported through the alliance (Req.3). For

example, the legal conditions and documents are

usually generated when needed, which can take a lot of

time and effort. The framework for knowledge transfer

helps to support these processes and enables the

sharing of best practices and documents within the

alliance. Harmonized documents and procedures can

be used in the university alliance to support the transfer

(Req.4). The structure and design of the framework

contributes decisively to the understanding of it and

delivers a great recognition factor (Req. 5). Due to its

resemblance to other models e.g. the Retail-H by

BECKER and MEISE, it is easily understandable (Becker

and Meise, 2008). The levels of the framework support

the understanding of its contents, as every level gives

greater detail of the level above. Future users are also

able to use these detailed levels to restructure their own

processes, as they represent harmonized procedures.

By creating the knowledge transfer framework, the

effort for the administration and maintenance of

processes can be reduced, because the processes in

only one framework must be maintained.

7 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

In this paper the two research questions RQ1 and RQ2

have been answered. The first question dealt with the

requirements for knowledge transfer in university

alliances. With the help of expert interviews, the

identified requirements were proven and justified (cf.

RQ 1). It was found that knowledge management in

university alliances is often difficult to pursue as

organizational structures of the single universities in an

alliance can diverge strongly from each other.

Nevertheless the creation of alliances and the third

mission in collaborations between universities of

applied sciences is gaining increasing importance

(Roessler Isabel, Duong Sindy, Hachmeister Cort-

Denis, 2015). This can not only be seen in the rise of

research projects in the field, but also in the current

need of companies to conduct transfer projects with

universities (IHK Bayern, 2017). The created artifact,

the framework for knowledge transfer in university

alliances, can enable this transfer and give a neutral,

networked and generally accepted presentation (cf. RQ

2). The evaluation shows that the framework can be a

means for knowledge transfer in university alliances.

The documentation of knowledge transfer and its

corresponding processes is essential to collaborate in

an alliance of universities. Also errors in existing

process definitions of the single universities can be

identified and potentials for optimization can be

recognized through the implementation of the

suggested framework.

Table 1: Core Processes and corresponding Subordinate

Processes of knowledge transfer.

Core Processes

Subordinated Processes

Internal

Scouting

Make Contact,

Scout Researchers,

Assess Needs,

Collect Demands

Requirement

Analysis

Define Target Groups,

Make Contact,

Visit Company/Social Protagonist,

Identify transfer potential,

Collect Demands

Initiation of

Cooperation

Opportunities

Matching of needs and demands,

Establishing of contact between

researcher and company/social

protagonist

Cooperation

Implementation of projects (e.g.

research projects, commercial

projects, thesis in collaboration with

e.g. companies, dissertations)

Scientific

Communication

Traditional Journalism,

Online Interaction and Social Media,

Organization and Documentation of

Events

Documentation

Project Documentation,

Calculatory Documentation,

Legal Documentation

Recursive

Transfer

Transformation of teaching

contents due to research results.

KMIS 2019 - 11th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

248

Limitations are given due to the conducted

evaluation in one university alliance. Future work

includes an evaluation in other university alliances.

The shown framework is the result of a revision

of former versions. Due to the results of the

evaluation, iteratively changes were made according

to HEVNER (Hevner and Chatterjee, 2010). The

current version will be developed and re-evaluated

further in future. Table 1 shows the currently

identified processes for future work. This list was

created as a result of the expert interviews, without

making claims in being complete.

Future work includes detailing the core

processes of knowledge transfer in form of value

chains and the modeling of relevant processes in

BPMN 2.0. Part of future work is also an

examination of the process of harmonization within

university alliances. Within the scope of the future

work, an adaptive reference model for

interorganizational knowledge transfer will be

created.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The transfer project "Transfer and Innovation East-

Bavaria" is funded by the "Innovative University of

Applied Sciences" East-Bavaria 2018 – 2022

(03IHS078D).

REFERENCES

BayHSchG (2006) ‘Bayerisches Hochschulgesetz’.

Becker, J. and Meise, V. (2008) ‘Strategie und

Ordnungsrahmen’, in Prozessmanagement: ein Leitfaden

zur prozessorientierten Organisationsgestaltung:

Springer.

Bouncken, R.B. et al. (2015) ‘Coopetition: a systematic

review, synthesis, and future research directions’, Review

of Managerial Science.

Bux, U. (2008) ‘Grenzschutz an den Außengrenzen:

Kurzdarstellungen über die EU’.

Clark, B.R. (1998) ‘The Entrepreneurial University: Demand

and Response’, Tertiary Education and Management.

Etzkowitz, H. and Leydesdorff, L. (2000) ‘the Dynamics of

Innovation: From National Systems and ‘‘Mode 2’’ to a

Triple Helix’.

Fritsch, M., Pasternack, P. and Titze, M. (2015)

Schrumpfende Regionen - Dynamische Hochschulen.

Froese, A. (2014) ‘Wissenschaftliche Güte Und

Gesellschaftliche Relevanz Der Sozial- Und

Raumwissenschaften’.

Gibbons, M. (1994) the New Production of Knowledge: the

Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary

Societies.

Hamel, G., Prahalad, C.K. and Doz, Y. (1989) ‘Collaborate

with Your Competitors - and Win’, Harvard Business

Review.

Henke, J., Pasternack, P. and Schmid, S. (2017) Mission, Die

Dritte: Die Vielfalt Jenseits Hochschulischer Forschung

Und Lehre.

Hevner, a.R. and Chatterjee, S. (2010) ‘Design Research in

Information Systems Theory and Practice’, Integrated

Series in Information Systems Volume 22.

Hoffmann, a. (2009) Entwicklung Eines Ordnungsrahmens

Zur Analyse Von Intraorganisationalem Wissenstransfer.

Holsapple, C.W. and Joshi, K.D. (1999) ‘Description and

Analysis of Existing Knowledge Management

Frameworks’, in System Sciences.

IHK Bayern (2017) ‘Innovationsreport Bayern’.

Jacobson, N., Butterill, D. and Goering, P. (2004)

‘Organizational Factors That Influence University-

based Researchers’ Engagement in Knowledge Transfer

Activities’, Science Communication, 25(3).

Meise, V. (2001) Ordnungsrahmen Zur Prozessorientierten

Organisationsgestaltung. Modelle Für Das Management

Komplexer Reorganisationsprojekte. Münster.

Meuser, M. and Nagel, U. (2009) ‘Das Experteninterview -

Konzeptionelle Grundlagen Und Methodische Anlage’.

Noelting, B. Et Al. (2018) ‘Nachhaltigkeitstransfer Von

Hochschulen’.

Pircher, R. (Ed.) (2014) Wissensmanagement,

Wissenstransfer, Wissensnetzwerke: Konzepte,

Methoden, Erfahrungen.

Powell, J.J.W., Baker, D. and Fernandez, F. (Eds.) (2017) the

Century of Science: the Global Triumph of the Research

University.

Rauter, R. (2013) ‘Interorganisationaler Wissenstransfer:

Zusammenarbeit Zwischen Forschungseinrichtungen

Und KMU’.

Roessler Isabel, Duong Sindy, Hachmeister Cort-Denis

(2015) ‘Welche Missionen Haben Hochschulen?’ CHE.

Ropohl, G. and Lenk, H. (1978) Systemtheorie als

Wissenschaftsprogramm: Athenäum Verl.

Seel, C. (2010) Reverse Method Engineering: Methode und

Softwareunterstützung zur Konstruktion und Adaption

semiformaler Informationsmodellierungstechniken.

Seel, C. and Dreifuß, F. (2014) ‘Induktive Entwicklung eines

Vorgehensmodells für Wissenstransfermaßnahmen in

der Wirtschaftsinformatik’.

Sturm, N. and Spenner, K. (2018) Nachhaltigkeit in der

wissenschaftlichen Weiterbildung: Springer Fachmedien

Wiesbaden.

Thiel, M. (2002) Wissenstransfer in komplexen

Organisationen: Effizienz durch Wiederverwendung von

Wissen und Best Practices.

Vorley, T. and Nelles, J. (2008) ‘(Re)Conceptualising the

Academy: Institutional Development of and beyond the

Third Mission’, OECD Higher Education Management

and Policy.

Wissenschaftsrat (2016) ‘Wissens- und Technologietransfer

als Gegenstand institutioneller Strategien |

Positionspapier’.

Collaborative Knowledge Management in University Alliances with Information Models

249