A Comparative Study on Transformation Process and Form of

Traditional Houses in Sumba Island

Mirzadelya Devanastya and Ayano Toki

Graduate School of Engineering Department of Architecture and Building Science Tohoku University, Japan

Keywords: House Form, Modernization, Sumba, Traditional House, Transformation

Abstract: In a society with no profession of architect nor engineer, the architecture transformation and the space

modification constantly carried out by the local community. Through this process, the local community had

been passed down their empirical knowledge, yet the tradition urged to alter its way according to the

modernization of the architectural culture and people's lifestyle. This study attempts to clarify the

transformation pattern of the traditional house in Sumba Island. We undertook the measurement of the houses

and interviews with the villagers in six villages located in the east and west. Through the comparison of six

villages, we identified clear regional differences in the transformation process and form of Sumbanese houses.

The typical Sumbanese house stands on stilts and topped with the impressive hat. The house has a hearth with

four main pillars surrounded by living space. In general, the transformation of the houses occurred in several

phases, in response to the increasing family members that consequently trigger the necessity of the new

facility. The transformation of form divided into two patterns according to their location, hilltop, and flat land.

These two types characterized by vertical/horizontal expansion of space according to topographical condition,

the changes of room layout in accordance with the religion of occupant, and the introduction of industrial

material which slowly replaces the natural material. We found that in the midst of the transformation process,

the form of high hat and the concept of the four main pillars were maintained. The villagers in Sumba put an

effort on balancing between modernization need and inheritance of the traditional value. The transformation

process shows a manifestation of the adaptation capabilities of traditional Sumba houses in response to the

modern needs of their residents, without sacrificing the important values that strictly maintained by the local

communities.

1 INTRODUCTION

The discussion on Indonesian vernacular architecture

has been held in many forums both national and

international. The term vernacular derived from the

Latin word Vernaculus, which means native or

domestic. Therefore, when it was combined with

architecture and creates the term vernacular

architecture, it gave the value of locality in the broad

meaning of architecture. Hence vernacular

architecture refers to building, which responded to the

needs of the specific people and reflecting the

character of the local environment. It is architecture

that becomes and processed by a particular society

that is located in a certain area (Allsopp, 1980).

Initially, architecture involved as an effort in the

provision of shelter from the surrounding

environment. However, the way architecture

responding to the environment is very dependent on

the knowledge and culture of the people. The culture

itself has characteristics of shifting along with the

passing of time, human knowledge will advance, and

the way we perceive things will be different.

Therefore, there will never be a static architecture.

Vernacular architecture itself will face various

changes in many aspects from the form, material,

even the spatial layout of the building.

The purpose of this research is to observe the

transformation of traditional houses by local people,

which happened in Indonesia in modern days. If

vernacular architecture is constantly changing, it may

be possible to trace and define the pattern of changes

throughout the years. It also aimed to establish a

deeper understanding of how the transformation

process took place in Indonesian vernacular houses,

especially in Sumba island. This understanding is

built on the knowledge of cultural values, which is

accompanied by a process of observation and pattern-

20

Devanastya, M. and Toki, A.

A Comparative Study on Transformation Process and Form of Traditional Houses in Sumba Island.

DOI: 10.5220/0013050700002836

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th Architecture Research and Design Conference (AR+DC 2019), pages 20-27

ISBN: 978-989-758-767-2; ISSN: 3051-7079

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

making that will be used as a basis in the effort to

translate the process of assimilating the thought

process of local citizens into architectural form.

2 THEORY/RESEARCH

METHOD

2.1 Theory

Pile dwelling houses in Indonesia are often thought to

be originated from granaries. In Sumba case, the

change from granaries to house is by adding a

platform beneath its floor and enclosed by walls

(Sato, 1991). In Sumatera, the Toba Batak has an old

custom of converting old sopo into dwellings through

a process of transformation that provided better kind

of ruma (Domenig, 2003). The transformations also

indicate the continuity of thought process in

consideration of priority value that has to be

maintained. Certain old features are still in evidence

in the house of Nage, which has undergone

considerable change (Forth, 2003). This suggests that

the house is not a static but a dynamic object, as it

undergoes change throughout the time.

2.2 Research Methods

The spatial archetype of a house can be seen by

observing the relationship between existential values

and the physical appearance of the interior of a house.

Observation starts by analyzing the space that

includes social dimensions and corresponds to a fixed

spatial arrangement (Barbey, 1993). The real essence

of this method is to see the relationship between

house, function, meaning and time as a process of

exchange between physical factors and spatial

dimensions. This method was first put forward by

Barbey when he saw the architect's lack of attention

about how everyday life affects the organization of

space, thought and arrangement of goods in it, or how

all these thoughts change within a certain timeframe.

Certainly, between everyday life and spatial planning

has a very strong influence on one another.

In the scope of traditional society, all elements in

the house have a strong influence and meaning, which

is the implication of the values or norms that are

always enforced. In this case, the community has first

acknowledged the relationship between house

elements and this understanding has kept their homes

well maintained. To better understand how the people

influence the form of their homes, field surveys and

interviews were held with both emic and etic

approach. Comparative analysis then applied to the

acquired data to identify the spatial hierarchy and

identify the pattern of transformation that took place

in the house.

Table 1. Analysis process scheme.

Methods Target Obtained

data

Analysis

Technique

Obtained

resul

t

Intervie

w

House

owner

and

family

members

House

transformatio

n history and

cultural

triggers for

each

transformatio

n phase

3D

conversion

and

comparativ

e analysis

of change

through

each period

of time.

House

transformatio

n pattern and

diagrams

Observat

ion and

measure

ment

Current

conditio

n of the

house:

Current

house form

Current

house form

used as a

compariso

n basis.

Hierarchy of

space and

archetype, as

well as the

existing

values of the

house

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Early Settlement and Distribution

Sumba is an island that belongs to the administrative

region of East Nusa Tenggara Province in Indonesia.

Stretches on the east side of Bali, the Nusa Tenggara

archipelago loses its tropical lushness and becomes

arid. Its proximity to Australia makes the transition

between tropical and dry climate. Therefore, when

other tropical islands are being characterized by its

fertility and vast jungle area, the environment in Nusa

Tenggara, including Sumba, tends to be dominated by

extensive grassland. The island is inhabited by people

with a mixture of Malay and Melanesian races and

adheres to the caste system in its social structure. This

condition has a major influence on the culture and

beliefs of Sumbanese people, which later will

intersect with their mindset that underlies the habit of

building their houses.

Marapu is the form of ancestral religion practiced

by the people on this island. The ancestors are

believed to be closely associated both in the form of

the house and the village arrangement as well. A

striking feature of the village layout is the intimate

connection between the dead and the living, of tombs

and houses, within the same space. This connection

resulting in the triadic division of space in the village,

with two opposing ends mediated by center

(Waterson, 1990). Therefore, every village has two

A Comparative Study on Transformation Process and Form of Traditional Houses in Sumba Island

21

entrance point on either side, and a field in the middle

with stone tombs erected on it.

Sumbanese house which called rumah adat in

Indonesian language has striking features in its form;

a wide thatched roof with a high towering hat in the

middle. This kind of house can easily be found

throughout the island, with variations in size and

height depending on its location, which will be

discussed in depth later on. The houses can be found

mostly in the villages, usually on the top of the hill,

or on the lowland near the river or beaches, depending

on the age of the village itself.

Sumba is culturally and politically divided into

western and eastern areas. The western part of Sumba

has been divided by warring fiefdom for centuries,

contrary to the east side which, although sparsely

populated, is more politically dominant. (Barry

Dawson, 1994). In terms of geography, Sumba island

is characterized into two regions; the eastern Sumba

with its vast savanna and hills, and western Sumba

with its mountainous topography and dense forest.

Six villages were observed in the process, and the

result discussion will be focused on classification by

hilltop and flatland villages.

3.1.1 Hilltop Village

The village located in the hilltop usually classified as

the old and sacred one. To reach this village, it

requires between 30 minutes to two hours hike to

reach depending on the accessibility from the nearest

road. Parewa Tana is one of the older established

villages on the western side of Sumba island.

According to the interview, the village was

established in approximately 1850. The house layout

is arranged in lengthwise in the north to the south line,

following the available space in the topographic

character of the site. Contrary to the character of the

flatland village, the houses in hilltops are mostly

arranged in parallel lines with the distance between

each house being really dense due to the availability

of the vacant land on the site.

The population of hilltops villages is currently

declining, on average of only inhabited by 50 people

or less, with mostly adults and elderly. This is due to

the fact that the majority of the youngsters decided to

move out of the village to the city for employment

reasons or being taken as the bride for other village

members. Therefore, the only remaining people who

still live in the village are the one who has a certain

position in the hierarchy of the village such as village

leader and indigenous elders.

3.1.2 Flatland Village

Contrary to the hilltop, the flatland village is located

in close proximity to big cities in Sumba. Most of the

flat land village is established as an expansion

settlement from the hilltop, as people came down to

work in the cities. The village characterized by having

a wider land area with groups of stone tombs erected

on the inner circle and several houses arranged on the

outer circle facing the tombs.

The majority of flatland village residents are

working in the cities and much more exposed to

technological progress. Therefore, their lives are

exposed to the many influences brought along with

the development of knowledge and technologies. The

ease of access to the village also influences the

change in religious belief from marapu to other

religions such as Christianity or Islam. This religious

transformation is one of the factors that greatly

influence the transformation of form and values in the

spatial hierarchy of the Sumbanese house.

Upon surveying the villages, the data is then

categorized to find and highlight the connection

between each village’s statistics and current physical

condition. Since the west Sumba was dominated by

hills and mountains, it is obvious that the majority of

the villages are established in the hilltop area. The

opposite also is seen in the eastern part of Sumba,

where the majority of villages are established on flat

lowland. Furthermore, by looking at the traced house

configuration image, the difference between the

hilltop and lowland villages are easily

distinguishable. The houses on the hilltop villages are

arranged in a line and the distance between houses is

very dense. The reason for this configuration can be

analyzed by comparing it with the aerial images, and

it is likely that the line shape is following the

character of the topography, as well as in the inner

circle boundaries of the surrounding forest. On the

other hand, the land in the lowland villages is much

wider than the hilltop one, and it can also be noted

that the distance between the houses is much wider.

AR+DC 2019 - Architecture Research and Design Conference

22

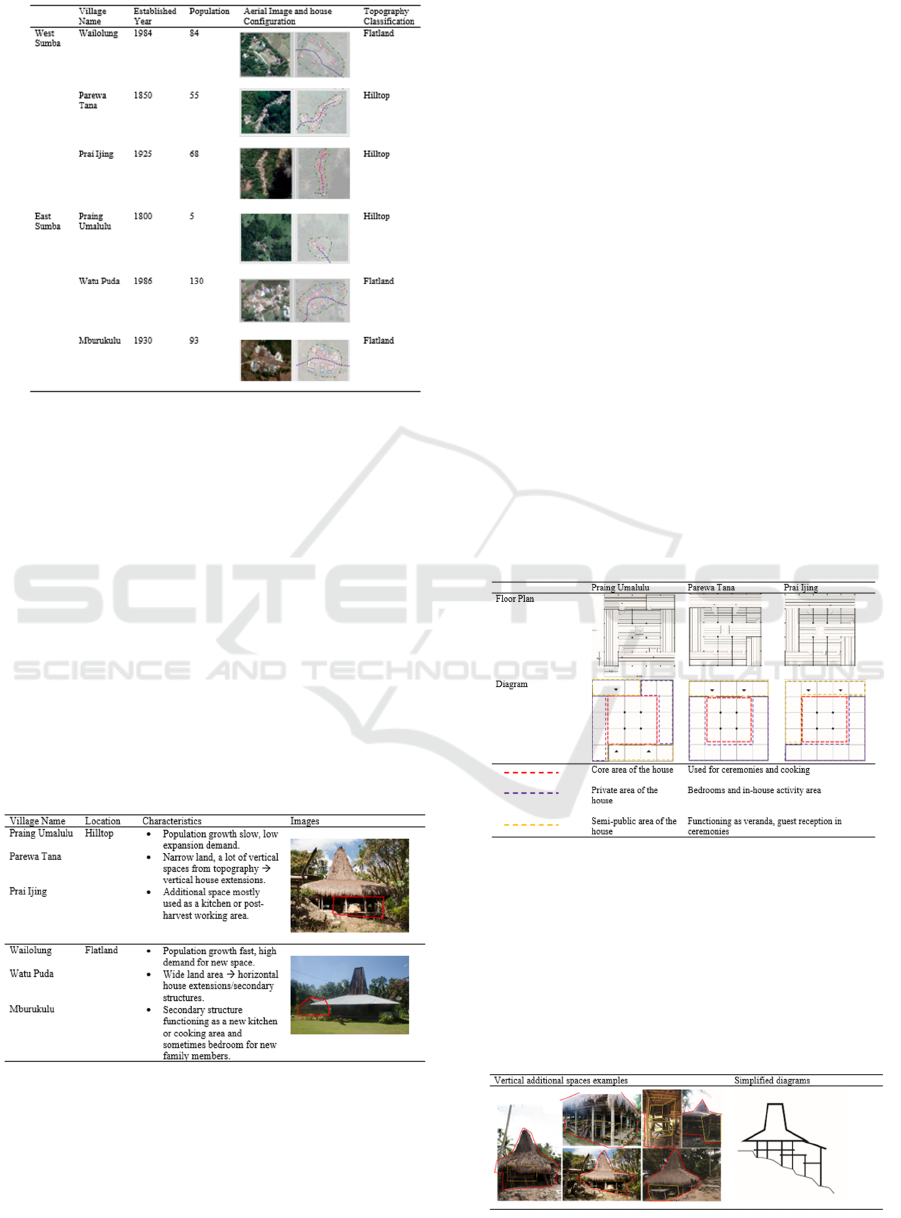

Table 2. Statistic data comparison between six villages

The differences in village characteristics are more

visible when grouped into two types: hilltop and

lowland villages. Topographically, the hilltop

villages are dominated by differences in land contours

which resulting in small areas of land that houses can

be built. With a tight distance between the houses and

being squeezed by ravines and forests, there is no

horizontal space left in the village. However, as the

population is growing, each house has a need to create

additional spaces for new family members. On the

contrary, the flatland villages have more spacious

land area, therefore the residents have more space and

freedom to develop their homes, following the

demand of the population increase.

Table 3. Village grouping based on topographical

characters

3.2 House Transformation Typologies

The transformation of the house of Sumbanese people

is a result of the adaptation of the people in response

to the changes in their daily lives and the sustainable

system imposed in the house construction methods.

The system is the building method that focused on

knockdown that provides easiness in assembly and

disassembling, resulting in the freedom to rearrange

the house configuration. The understanding of the

spatial hierarchy and division of space is achieved

through the conversion of floorplan into diagrams.

The comparative analysis of the diagrams of the

houses from different villages showing the current

forms, although different in some elements, has

particular rules that apply in all of the transformation

process. In the hilltop area where marapu religion is

still highly believed, the core area of the house

doesn’t experience significant transformations. The

four main pillars and inner hearth still act as sacred

place with only minor transformations are allowed

such as adding or removing partition walls. The walls

are built to accommodate the division of space

according to the numbers of family members. The

space surrounding the core area is more flexible in

experiencing changes in function. The house owners

can easily transform semi-public space such as the

veranda into private space to accommodate the need

of a bedroom as the family member grows from time

to time.

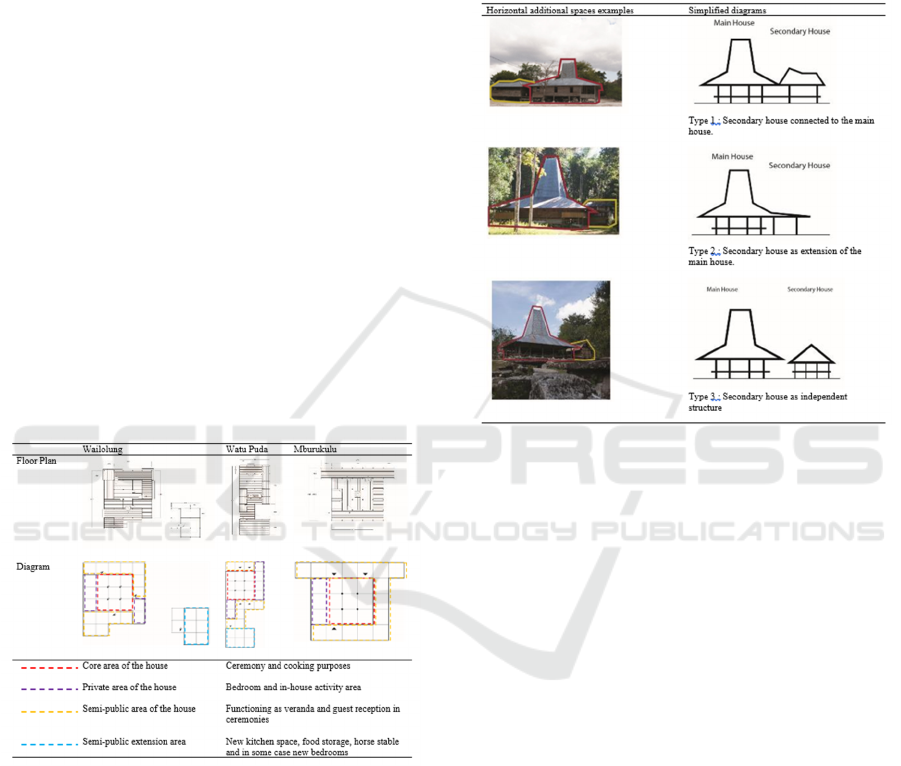

Table 4. Hilltop village house sampling and diagrams

Along with the growing number of family members,

the need for space constantly increases. The

limitation of the land area in the village compels the

villagers to outsmart it by constructing new spaces

vertically, taking advantage of land contours. Vertical

transformation becomes a pattern that mainly adapted

and developed over time in the hilltop villages.

Table 5. Vertical additional space in hilltop villages.

A Comparative Study on Transformation Process and Form of Traditional Houses in Sumba Island

23

The houses in flatland villages undergo a more

varied transformation pattern compared to the hilltop

villages. Land availability triggers a more varied and

flexible transformation pattern, unlimited by the

envelope of the main house. As the majority of the

people changed their religion into Christianity or

Islam, any house elements related to the marapu must

be removed. This highly affects the core space of the

house as the inner hearth that acts as a pivot in

ceremonies is removed entirely from the house.

However, the removal of the inner hearth also meant

losing the cooking area, which usually responded by

constructing a new kitchen outside of the main house

area. The variety and flexibilities of transformation in

flatland area also affected by the modernized and

adaptation of new lifestyle that gradually introduced

by both government programs and the increasing

number of young family members who attends higher

education level. Amenities such as electricity,

television, piped water, cement paths, factory cut

wooden materials, and corrugated iron or zink roofing

is a common thing to find. Thus the transformation

that occurred in the houses is more rigid and

permanent, utilized in the long run.

Table 6: Flatland village house sampling and diagrams.

From the observation on flatland village extension

patterns, there are three types of secondary

house/structure typologies. The first type is the

secondary house that connected to the main house by

the floor, however, it has separate and independent

roofs and structures. Although the secondary houses

are built independently, it has floor connection to the

main house for easy access purpose. The second type

is the secondary house as extension part of the main

house. This type occurs in a house where the owner

of the house only have limited ownership of the land

in the village. The third type is the secondary house

that completely separated and structurally

independent from the main house. The third type

usually established in wealthy family house where

they can afford to build large kitchen areas, and

sometimes also includes the addition of other room

functions such as bedrooms and horse stables

Table 7. Horizontal additional space in flatland villages.

3.3 House Transformation Phase

Tracing the transformation history of houses in

Sumba also implies tracing the social history of the

said house. This attempts to indicate the connection

of events on the particular years that influence

significant transformation to the chosen house.

Through the interpretation of existing construction

language, combined by the stories of the owner of the

houses as well as the neighbors who helped in the

construction process, it can clearly be assumed that

the house experienced several transformation phases

in the process. From the hilltop house transformation

diagrams, there are two villages with whom the house

experienced major transformation. With the

exception of the house in Praing Umalulu as the

village is considered sacred and spatial

transformations are prohibited by the marapu

religious leaders. The strictness of these rules is an

indicator to be considered that this house has the basic

form of Sumbanese traditional house.

From the three-dimensional interpretation (figure

1 and 2) there is a difference in thought patterns

between hilltop village dwellers and flatland villages

in creating additional space in their houses. There are

several important factors that need to be taken into

account in understanding the transformation process

of houses in hilltop villages. First, its topographical

AR+DC 2019 - Architecture Research and Design Conference

24

characters force people to look for chance to

transform while keeping in the boundaries of marapu

rules and make use of what they already have in their

environment. This means the keeping of core area

intact and divert to converting space that is less

influenced by religious provisions. Thus the people

tend to convert the semi-public veranda into private

bedroom by adding walls or creating additional

platforms on the side or under the house. Secondly,

the access difficulty of the village creates limitations

in the distribution capabilities of materials that

originated from the cities. This means the lack of

external influence in the transformation process,

making the ancestral knowledge of building methods

intact. This can be seen on the partition walls made of

natural materials such as bamboo and wooden deck

floor that are made easily dismantled anytime. This

method provides flexibility values that are utilized by

the residents of the house to change the arrangement

of space at any time as needed.

Flatland village houses on the other hand have

more freedom in their transformation experience.

First of all, the flatland villages are usually

constructed as settlement derived from the hilltop

village, as an effort to create easier access to and from

the cities. Many hilltop villagers decided to move

down the hill to settle in these villages. Contrary to

the hilltop village, the communities in flatland

villages are more open to the external influence

brought in by the migrants or the citizens who study

or working in the cities. This acceptance of external

factors influence heavily on the development of

people’s mindset, including the patterns and house

building methods. The decline in marapu religion is

one of the indicators which on one hand erases a lot

of values in the house, but on the other hand, becomes

a substantial factor in creating opportunity for the

flexibility of major changes in their homes that

triggers the emergence of secondary structure.

This interesting development appears to involve a

fundamental change in the way of living in

Sumbanese society. The majority of secondary

structures allocated as kitchen with some additional

space such as other bedrooms or horse stable,

depending on the needs of the homeowner.

Interestingly, the building method of the structure is

the combination of old knowledge with the use of

modern building materials, especially for the roofing.

The hearth part, still using the similar block of stone

pedestal propping up the fireplace and encircled by

four roofing pillars. This effort to maintain the hearth

as closely related to old hearth they had removed

shows that although it has been moved to a place

separated from the main house, the kitchen as space

and cooking activities still regarded as closely related

to their ancestral values. Other spatial functions such

as food storages were moved with the same layout

concept, over the hearth to ensure the benefit from

smokes from the hearth. Therefore, even though the

moving of the hearth from the main house also

implying the moving of core activity area to the

secondary structures. As the hearth removed and the

activities changes, the core of the main house remains

as symbolic of the culture and status shown to the

general public

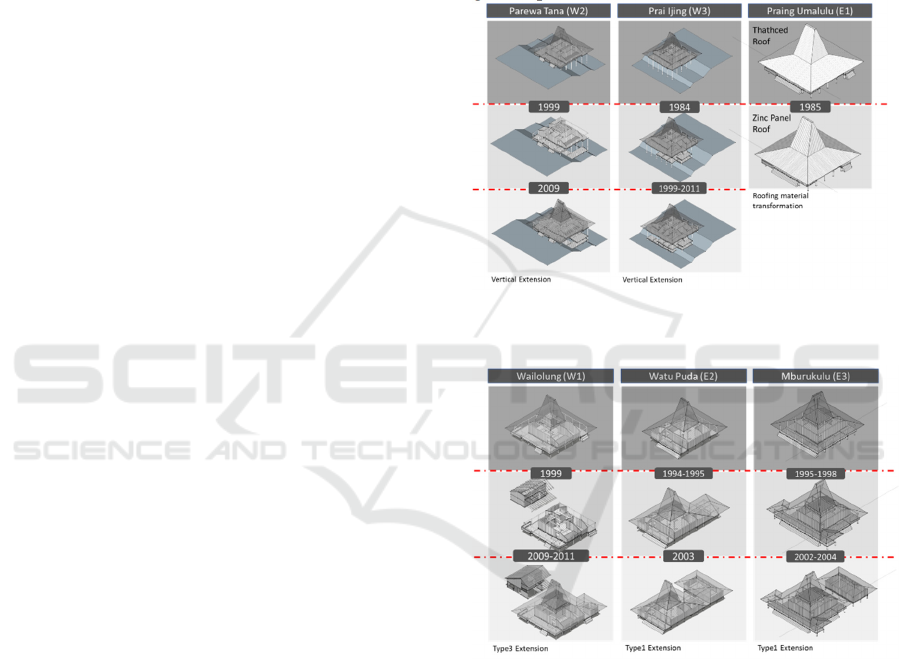

Figure 1. Three-dimensional interpretations of house

transformation phases in hilltop villages.

Figure 2. Three-dimensional interpretations of house

transformation phases in flatland villages.

A Comparative Study on Transformation Process and Form of Traditional Houses in Sumba Island

25

Table 8. Transformation phases informations.

The transformation table above indicated that there

are two types of transformation in a house. Minor

transformations such as maintenance and

replacement of old materials that happened frequently

once every three to four years were not mentioned in

the table as it did not affect the house form

significantly. Major change on the other hand occurs

gradually and divided into several phases. It is

interesting that from the 6 houses, the phases can be

collected into two groups. The first phase of

transformation in hilltop village occurred in the span

of the 80s to the 90s where most of the

transformations are making a new bedroom. This is

quite contrary to the flatland villages as the majority

of the new bedroom constructions occurred in the

second phase. This may suggest the gap of the

emergence of new generations between those

villages, indicating the declining of the village

population as there are no demands for the new rooms

on the second phase of the hilltop village in a similar

timescape.

In the flatland village, the transformation phases also

can be grouped into two time frame where the first

one occurred in a much longer span between 1994 to

1999 and the second phase is between 2002 to 2011.

For a village that the majority of the people converted

into non-marapu religion, ceremonial associated

inner hearth was the main element of the house that is

removed and triggers the construction of new kitchen

area as replacement of cooking space. On the other

hand, there are socio-economical factors that affect

the transformation of flatland village as more of the

young population attend to higher education and

bring knowledge into the village communities. As a

result, there is tension between ancestral practices

pertaining to the free but time-consuming application

of natural material to modern knowledge and the idea

of time-saving but money consuming prefabricated

house materials.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The comparative analysis on transformation of house

form in Sumba indicates the strong connection

between the topographical location of the houses and

the transformation pattern that occurred. The

transformation in Sumba houses are divided into two

axes, either vertically or horizontally, and the location

of the house greatly influences the direction of

change. In a hilltop village, the transformation is done

vertically, creating a trade-off between the limitations

on internal space modification caused by religious

factor and dense layout between the houses, with

flexibility utilizing empty space under the house. On

the other hand, the flatland village house utilizes the

abundance of land availability which enhances the

flexibility in repurposing and transforms the form of

the house.

The changes in socio-cultural factors on village

communities also influence the type of necessities

that triggers the form of newly constructed facilities.

The hilltop villages focus on constructing new

bedrooms to get around the growing number of

family members. The persistence of marapu religion

creates limitations in transforming the core part of the

house, leaving it intact until current time. In flatland

villages, marapu religion has faded resulting in the

removal of strongly related house element especially

the hearth. Thus the majority of new erected space is

appointed as kitchen. Moving the kitchen from the

main house to the outside also impacts the kind of

activities took place inside the main house. The main

house become solely used for sleeping and receiving

guest, and the other family gathering activities

happen around the kitchen in the secondary structure.

This research implies that in a society where there is

no profession such as architects, the house evolved by

constant spatial modification carried out by the local

community. Through this process, the knowledge of

local architecture not only passed down to the newer

generation but also received new values that influence

the form of the house. Therefore, the research on this

topic should be discussed more frequently to maintain

the updated analysis on the latest form of the house.

AR+DC 2019 - Architecture Research and Design Conference

26

REFERENCES

Adams, R. L. (2008). The megalithic tradition of West

Sumba, Indonesia: An ethnoarchaeological

investigation of megalith construction. Dissertation

Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and

Social Sciences, 69(4-A), 1415.

Adams, R. L., & Kusumawati, A. (2010). The social life of

tombs in west Sumba, Indonesia. Archeological Papers

of the American Anthropological Association, 20(1),

17–32.

Alone, S., Liang, T. M.-, & Laxton, W. (n.d.). Breathless :

Making Build- ings and Weather on Sumatra. 72–82.

Asih, E., & Dwi, A. (2015). Gendered Space in West

Sumba Traditional Houses. DIMENSI (Journal of

Architecture and Built Environment), 42(2), 69–75.

Asquith, L., & Vellinga, M. (2006). Vernacular

Architecture in the twenty-first century. 313.

Creangǎ, E., Ciotoiu, I., Gheorghiu, D., & Nash, G. (2010).

Vernacular architecture as a model for contemporary

design. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the

Environment, 128(March), 157–171.

Ellen, R. F. (2013). Microcosm, Macrocosm and the

Nuaulu house: Concerning the reductionist fallacy as

applied to metaphorical levels. Bijdragen Tot de Taal-,

Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and

Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, 142(1), 1–30.

Ellisa, E., & Pandjaitan, T. H. (2015). INTERIOR

ARCHITECTURE OF VERNACULAR MBARU

NIANG OF WAE REBO ( Toga H . Panjaitan ,

Evawani Ellisa ) INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE.

(September 2016).

Gruber, P., & Herbig, U. (2005). Research of

Environmental Adaptation of Traditional Building.

Architecture, (Hb 2).

Hourigan, N. (2015). Confronting Classifications - When

and What is Vernacular Architecture? Civil

Engineering and Architecture, 3(1), 22–30.

Mross, J. W. (2000). Cultural and Architectural Transitions

of Southwestern Sumba Island, Indonesia. Acs4 2000

International Conference, 260–265.

Muslimin, R. (2017). Toraja Glyphs: An Ethnocomputation

Study of Passura Indigenous Icons. Journal of Asian

Architecture and Building Engineering, 16(1), 39–44.

Pandjaitan, T. H., & W, A. B. (2017). Transformed Seabed

of the Sama Bajau The Disappearance of Coastal

Vernacular Settlements [ Pick the date ] Transformed

Seabed of the Sama Bajau. (April).

Panjaitan, T. H. (2017). Hybrid Traditional Dwellings:

Sustainable System in the Customary House in Ngada

Regency. International Journal of Technology, 8(5),

841.

Rashid, M., & Ara, D. R. (2015). Modernity in tradition:

Reflections on building design and technology in the

Asian vernacular. Frontiers of Architectural Research,

4(1), 46–55.

Sato, K. (1991). Menghuni Lumbung: Beberapa

Pertimbangan Mengenai Asal-Usul Konstruksi Rumah

Panggung di Kepulauan Pasifik. Jurnal Antropologi

Indonesia, no.49, 31-47.

A Comparative Study on Transformation Process and Form of Traditional Houses in Sumba Island

27