Social Enterprise and Waqf:

An Alternative Sustainable Vehicle for Islamic Social Finance

Noor Suhaida Kasri and Siti Fariha Adilah Ismail

International Shariah Research Academy (ISRA), Malaysia

Keywords: Social Enterprise, Waqf, Larkin Sentral, Warees Investment, Pondok Modern Darussalam Gontor.

Abstract: Social Enterprise (SE) is a business entity which investment is driven by the need to create economic and

social value for the community and environment. The sustainability and viability of SE implementation in

Europe has propelled it to be an essential part of European economic model and key in promoting social

cohesion and democracy. However, the growth of SE in jurisdictions that lead Islamic social finance is not

much visible. Instead the presence of social vehicles namely waqf, zakat and sadaqa tend to be widely

accepted, for example in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. This paper aims to examine SE and highlights

SE best practices that waqf establishments can emulate particularly from the aspect of sustainability and

transparency. Comparative analysis is carried out on SE entity of Bangladesh Rural Advancement

Committee and three waqf entities namely, Malaysia’s Larkin Sentral Property Berhad, Singapore’s Warees

Investment Ptd Ltd and Indonesia’s Pondok Modern Darussalam Gontor. The analysis shed light on their

sustainable business model including their governance, transparency and social impact made. This paper

adds value to the waqf sectors globally in the search for alternative sustainable and viable contemporary

waqf model

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Islamic social finance is one of the subsections in

Islamic financial system that integrates economic

activities with social value. Their activities enable

communal socio-economic issues addressed hence

results to positive socio-economic impact

(Mahomed, 2017). On that premise, social finance,

as the third sector provides the community with

basic necessities when government and market,

being the first and second sector, have failed or

unable to provide such facilities to the public

(Anheier, n.d). The same with Islamic social finance

where activities and instruments involving waqf,

zakat and ṣadaqah are used to deliver activities with

socio-economic impact (Mahomed, 2017). At a

larger scale, organisation and enterprises like

cooperatives, mutual benefit societies, associations,

foundations and social enterprises are established as

vehicles to execute the social economic activities

(ILO Social Economy, 2010).

1.2 Objective

While the need and demand for social economic

activities persist particularly in the current state of

global economy, sustaining these vehicles remain a

fundamental issue. Sustainability aids these

establishments to continuously deliver their social

key performance targets. With the right and strategic

sustainable structure and governance model, the

survival of these entities as well as their social

economic activities can be guaranteed. Due to its

significance, this paper opts to explore social

enterprise and waqf entities and discern from their

best practices aspect of sustainability and

transparency. This paper has selected one social

enterprise, Bangladesh Rural Advancement

Committee (BRAC) and three waqf entities namely,

Malaysia’s Larkin Sentral Property Berhad (Larkin

Sentral), Singapore’s Warees Investment Ptd Ltd

(Warees Investment) and Indonesia’s Pondok

Modern Darussalam Gontor (Pondok Gontor). The

reason for their selection is due to them being

recognised as among the most sustainable and

impactful entities by their local peers and abroad.

218

Kasri, N. and Ismail, S.

Social Enterprise and Waqf: An Alternative Sustainable Vehicle for Islamic Social Finance.

DOI: 10.5220/0010120800002898

In Proceedings of the 7th ASEAN Universities International Conference on Islamic Finance (7th AICIF 2019) - Revival of Islamic Social Finance to Strengthen Economic Development Towards

a Global Industrial Revolution, pages 218-230

ISBN: 978-989-758-473-2

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Background Theory

According to BRAC, social enterprise is a self-

sustaining cause-driven business entity that create

social impact by offering solutions to social

challenges and reinvesting their surpluses to sustain

and generate greater impact (BRAC, 2018). Besides

striving to meet the need to maximize profit, social

enterprise is also expected to tackle environmental

and economic issues (Department Trade and

Industry, 2002). The origin behind the idea of non-

state/non-private enterprise can be traced back to the

nineteenth century. As capitalism advanced, there

were growing calls by groups of people linked to

religious, political-ideological and other

organizations such as voluntary associations,

charities and co-operatives to pacify the increased

public unrest associated with the intensification of

capitalist social relations of production and

industrialization. The burgeoning need to address the

social and economic need in the society was

conspicuous. These developments propel the notion

of ‘social economy’, within the continental

European tradition, and ‘non-profits’ in the US

tradition and ‘voluntary’ and ‘charity’ within the UK

tradition (Sepulveda, 2015). Today social enterprise

have been duly recognised and their establishment

are being implemented through legal structures like

company limited by guarantee, industrial and

provident societies, companies limited by shares,

unincorporated organisation or registered charities

(Department Trade and Industry, 2002). Some

examples of accoladed social enterprises are

Ashoka, Grameen Danone, DC Design, Big Issue

and BRAC.

Waqf is the locking up of title and ownership of

an asset from disposition and allotment of its benefit

for a specific purpose or purposes. The ownership of

the waqf asset cannot be transferred (perpetuity) and

the benefits are to be used in accordance with the

direction or meeting the aim of the donor which is

(are) mainly charitable in nature (Sadeq, 2002). In a

hadith of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him)

whereby he directed Uthman Ibn Affan to purchase

the well of Bi’r Rumah for 20,000 dirham. Uthman

Ibn Affan purchased the well and endowed it for the

use and benefit of the muslim and non-muslim

communities in Madina. Despite centuries have

passed, the waqf of Bi’r Rumah is still serving

humankind today. This practice laid down the

foundation for waqf funds being invested towards

serving and making social and economic impact to

the society. In this modern age, waqf is applied in

multitude forms be it liquid and illiquid assets for

example immovable and movable assets including

cash and shares. These practices can be observed in

institutions like Waqaf An-Nur Corporation Berhad,

Larkin Sentral, Warees Investment, Daarut Tauhid,

Rumah Wakaf Indonesia, Tabung Wakaf Indonesia

and Pondok Modern Darussalam Gontor.

2.2 Previous Studies

Much have been written on social entrance and waqf

though they are written independently without

connecting to one another. Therefore writings on

social enterprise and waqf as one subject is still

scarce. However lately few writings have emerged

that converged social enterprise and waqf. Anwar

(2017) mentioned that one of the reasons why waqf

has yet to generate good return was because of their

lack in strategic investment strategies. One of the

examples quoted was waqf assets being locked in

expensive real estate and faced with high

maintenance and management costs. Anwar (2017)

and Salarzehi, et. al. (2010) therefore proposed for

waqf institutions to explore alternative investment

vehicle for instance waqf-social entrepreneurship

model which is designed to make social impact as

well as generate profits. Similar line of suggestion

was advanced by Muhamed, Kamaruddin and

Nasruddin (2018) where they proposed for Islamic

Social Entrepreneurship (ISE). ISE is presented as

an Islamic based entity that gained funding from

Islamic charitable sources (through waqf, sadaqah,

hibah and qard) and channelled them to business

activities for sustainability purposes as well as

making social impact. Noor, Sani, Hasan and

Misbahrudin (2018) also advocated for waqf to be

adapted into the enterprise-business model to ensure

the sustainability of the entity.

Although these studies have presented ways for

waqf institutions to integrate with the social

entrepreneurship model, the literature are mainly

theoretical that are short of practical parts. Hence

this study addresses this gap by showcasing the real

examples of best practices of integrated model of

social entrepreneurship and waqf. The choice of

these real examples is made based on the evidence

of sustainability and transparency in their businesses

and organisations. These mini case studies will

render lessons on international best practices for

other waqf peers to learn and follow.

Social Enterprise and Waqf: An Alternative Sustainable Vehicle for Islamic Social Finance

219

2.3 Methodology

In terms of research methodology, this paper

employs qualitative research using the textual

analysis approach. Data gathered from on-line

sources particularly the respective entities’ Annual

Reports, reports, academic writings, newspapers,

websites and others are referred to in understanding

the context and operation of these establishments.

The analysis made from these data accentuate the

sustainable operating model of these entities

including their best practices, governance,

transparency and social impact made. Due to

BRAC’s outstanding social economic

accomplishment, it will be used as the benchmark

for waqf institutions to adapt and emulate

particularly from the angle of sustainability and

transparency. This study contributes to the literature

on Islamic social finance particularly waqf as it

highlights viable sustainable social enterprise best

practice for waqf establishments to learn and adapt

whenever applicable and practical.

3 RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

3.1 Analysis

3.1.1 Establishment

The four selected organisations share a number of

common factors. They are all located in the Asian

region, while BRAC is located in South Asia, Larkin

Sentral, Warees Investment and Pondok Gontor are

in SouthEast Asia. Due to that, they share more or

less the same climate. Except for Singapore, the

majority of the population in Bangladesh, Malaysia

and Singapore are Muslims. Yet the majority of ultra

poor or poor people are Muslims. This reality spurs

the comparative analysis of these mini case studies

in exploring the sustainable best practice models.

BRAC is one of the largest NGO in the world,

operating across eleven countries in Africa and Asia.

BRAC was ranked first among the world’s top 500

NGOs by Geneva-based ‘NGO Advisor’ in terms of

impact, innovation and sustainability (BRAC, 2018).

Established for almost half a century, BRAC started

way back in 1972, in the aftermath of the Liberation

War in Bangladesh. The original mission of BRAC

was to act as a temporary relief organisation for the

millions of refugees as the government lacked the

capacity to aid these refugees. During this period,

BRAC witnessed a host of social problems at a

national scale and the conspicuous failure of

government agencies in providing sufficient relief.

Due to this reality, in 1974, BRAC changed its name

from ‘Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance

Committee’ to ‘Bangladesh Rural Advance

Committee’. They then changed their mission from

merely providing humanitarian relief to addressing

the fundamental underlying socio-economic problem

- eradicating extreme poverty in Bangladesh (Seelos

& Mair, 2006).

Larkin Sentral was originally a private limited

company. In 2016, it was then changed to a public

company limited by guarantee. The conversion of its

legal status allowed it to issue cash waqf initial

public offering (IPO) to the Malaysian market. The

purpose of the IPO is to create awareness of the

concept of waqf and to provide opportunity for the

public - Muslims and non-Muslims - to contribute

towards the socio-development of the society. The

proceeds from the issuance of the cash waqf shares

will primarily be used to support and facilitate the

upgrading and refurbishment of Larkin Sentral

Transportation Terminal and Wet Market in Larkin,

Johor. Johor is located at the southern end of

Peninsular Malaysia. The proceeds from the IPO

exercise will be used to purchase a piece of land

adjacent to the Larkin terminal for the purpose of

developing it into the terminal’s multi storey car

park (Larkin Sentral Project) (Prospektus Larkin

Sentral, 2017).

Larkin Sentral is a subsidiary of Waqaf An-Nur

Corporation (WANCorp). Both Larkin Sentral and

WANCorp are under one parent company, Johor

Corporation (Jcorp). WANCorp is the appointed the

nazir (manager) to the shares and other securities

endowed by JCorp. Besides managing the endowed

assets and shares of Jcorp Group, WANCorp is also

appointed as the nazir khas (private trustee) for

Larkin Sentral’s cash waqf shares. The management

of these endowed shares and securities is supervised

by Johor Islamic Religious Council (JIRC). In

Malaysia, each of its State’s Islamic Religious

Council (SIRC) is the sole trustee of all waqf

properties. They are referred to as nazir am (public

trustee). Nonetheless in certain situations, private

trustee can be appointed to manage and administer

the waqf property under the supervision of the

respective SIRC which is practiced in the case of

WANCorp and Larkin Sentral (Prospektus Larkin

Sentral, 2017).

Warees is an acronym for WAkafREalEState.

Warees Investment was established in 2002 by

Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS). Its

mandate is to develop prime commercial and

residential properties as well as conserving the

7th AICIF 2019 - ASEAN Universities Conference on Islamic Finance

220

culture and heritage. Warees Investment specializes

in managing endowments and institutional real

estate portfolio and several subsidiaries. In doing so,

it ensures that value is created for the community

and its social beneficiaries. Warees Investment has

managed a total of 156 waqf properties/assets across

Singapore with a value worth SGD769 million

(USD564 million). Out of that 156 properties/assets,

85 are MUIS-managed wakaf assets and the balance

71 assets are mutawalli-managed. In accordance

with the Singapore Administration of Muslim Law

Act (AMLA), ‘mutawalli’ refers to a person

appointed to manage a waqf or mosque and includes

a trustee (Warees, 2019a).

Since its establishment, Warees Investment has

transformed many of the unproductive awqaf land

into huge commercial and residential areas. Where

there are no private trustee for the particular Waqf

concerned, MUIS become the trustee and engage

Warees to act as the mutawalli to manage and

develop the asset. Appointment of all trustees and

mutawallis have to be approved by MUIS. The same

with the retirement of these trustees. This

monitoring is necessary to ensure that the record of

trustees or mutawallis is centrally documented and

kept (Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura, 2019).

Pondok Gontor is regarded as one of the oldest

waqf institutions in Indonesia (Fasa, 2017). It was

initially known as Gontor Lama or Gontor Generasi

Pertama (Masruchin, 2014a). It has been built in the

eighteenth century by one prominent Islamic

scholar, Kyai Sulaiman Jamaludin, a student of the

prominent Kyai Khalifah, the founder of Pondok

Tegalsari. Kyai Sulaiman Jamaludin was trusted by

Kyai Khalifah to set up his own pesantren in Gontor.

Gontor is located in the southeast of Ponorogo,

Indonesia. At the initial stage of its set up, Gontor

Lama received only forty students though the

number gradually increased. However during the

third generation of the administration of Gontor

Lama, this development got stagnated and the

students intake was significantly reduced. This led to

the fourth generation known as Trimurti - Kyai

Ahmad Sahal, Kyai Zainuddin Fannani and Kyai

Imam Zarkasyi, revolutionary action that

modernized Gontor Lama in 1926 (Dacholfany,

2015). The name of Gontor Lama then changed to

Pondok Modern Darussalam Gontor. The

modernization affected not only the education

system but also its management (Aswirna et al.,

2018). Today Pondok Gontor hosts about 26,000

students, having 17 pondok cabang (branches), one

institution for male students (Kulliyyatu-l-

Mu’allimin Al-Islamiyyah Gontor Putra), five

institutions for female students (Kulliyatu-l-

Mu’allimat Al-Islamiyah Gontor Putri) and one

Darussalam Gontor University (Pondok Modern

Gontor Darussalam, 2019).

3.1.2 Governance and Transparency

Governance plays a big role in ensuring the

organisation’s strategic planning is successfully

implemented. Organisation that is led by forward

and objective thinking, passionate and mature

leaders helps in instilling good working culture and

driving the growth of the organisation to a higher

level. Transparency is also another best practice that

is deemed compulsory for organisations that deal

with public financing and donations. These

prerequisites are visible in these selected case

studies.

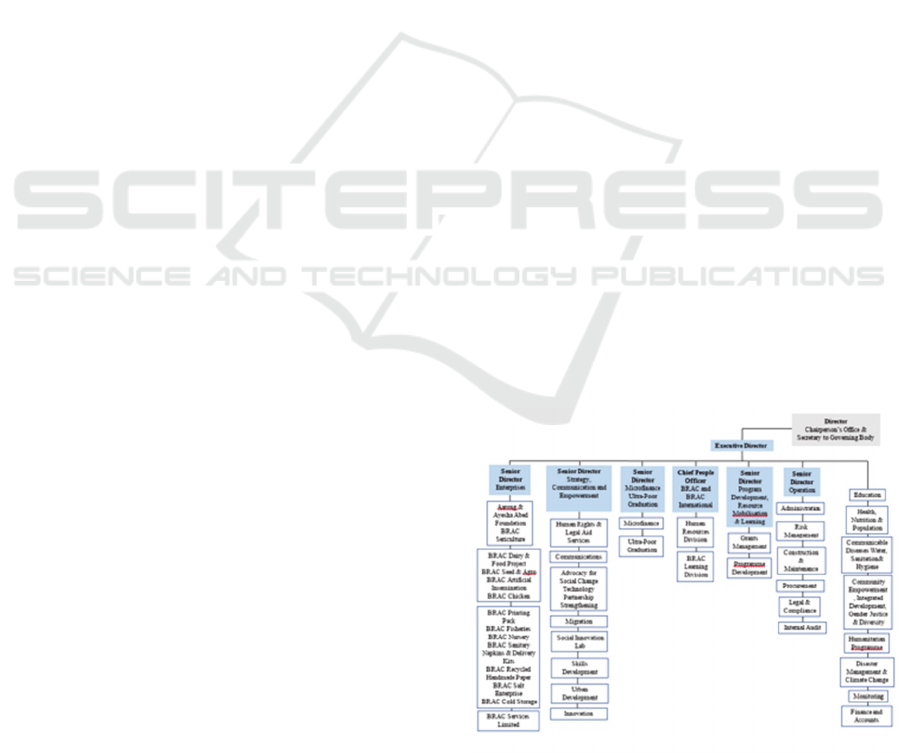

BRAC is governed by a 10 member governing

body that comprise of distinguished professionals,

activists and entrepreneurs of excellent repute. Their

expertise, skills and experience have driven BRAC

to a globally recognised reputable standard. BRAC

has also networks outside Bangladesh and they are

governed by BRAC International Supervisory

Board. The successful implementation of BRAC’s

programs and initiatives that abled to reduce extreme

poverty and empower the poor have proven the

stature of its governing body and management team.

The credibility and quality of BRAC’s governance is

reinforced by the ‘AAA’ rating by Credit Rating

Agency of Bangladesh Ltd. The ‘AAA’ rating

reflects BRAC’s extremely strong capacity and

highest quality in meeting its financial commitments

(BRAC, 2018). The organisational structure of

BRAC is further described in Diagram A below.

Figure 1: BRAC’s Organogram. Source: (BRAC, 2018).

Social Enterprise and Waqf: An Alternative Sustainable Vehicle for Islamic Social Finance

221

In addition to BRAC’s calibre leadership and

management team, BRAC have also engaged key

government stakeholders. The engagement and

collaboration with the local and foreign ministries

and organisations enabled BRAC’s programs to

scale up and be more impactful. Among the local

government ministries that BRAC is in alliance with

are: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Food,

Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Health and

Family Welfare, Ministry of Social Welfare,

Ministry of Industries, Ministry of Women and

Children Affairs. BRAC are also in partnership with

the UK and Australian government through the

Department for International Development and

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

respectively. The core funding provided by these

parties have facilitated BRAC to tackle the key

development challenges more efficiently and

effectively (BRAC, 2018).

As part of its disclosure and transparency best

practice, BRAC started publishing its Annual Report

from year 2012 and Audit Report from 2008 (based

on the uploaded reports in BRAC’s website). The

annual report covers and highlights the activities and

achievements accomplished in the reported year

especially meeting its vision and mission including

governance and financial. BRAC reports not only

activities held in Bangladesh but also activities

hosted by its networks across the globe namely

Afghanistan, Liberia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan,

Philippines, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania,

Uganda, UK and USA. Key information that is

being shared in its report instil confidence and trust

into BRAC’s commitment in delivering its promise.

Hence it is not surprising that BRAC has abled to

garner the support from credible philanthropists and

charitable institutions like Bill & Melinda Gates

Foundations, Qatar Foundation, UNICEF, UNHCR,

European Union, Kingdom of the Netherlands,

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark and others

(BRAC, 2018).

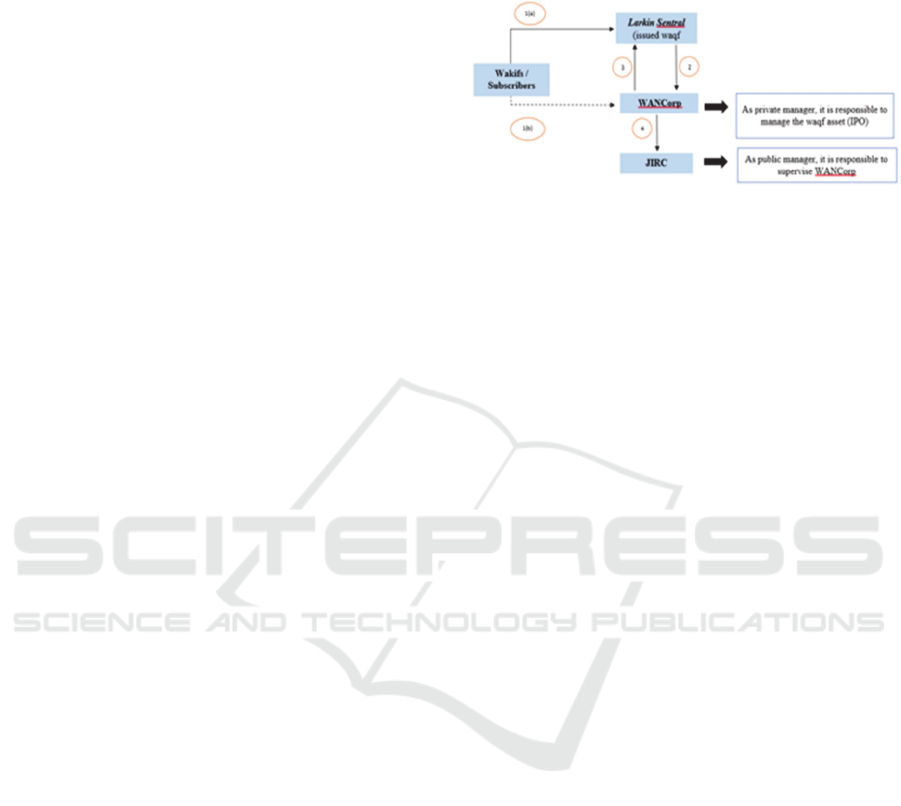

As mentioned previously, Larkin Sentral is a

wholly owned subsidiary of WANCorp and both,

WANCorp and Larkin Sentral are under one parent

company, JCorp. Due to this subordination nature,

WANCorp and JCorp sits on Larkin Sentral’s board

of directors. The board of directors also host other

Jcorp’s subsidiaries - Johor Land and TPM

Technopark Sdn. Bhd, and two other independent

directors. At current, the background of the

independent directors are business management and

law. Their presence adds value to the company by

ensuring prudent and proper execution of the

mandate given to the company (Kasri & Shukri,

2020). Diagram B shows the Larkin Sentral’s

governance structure which portrays WANCorp and

JIRC in the waqf asset management.

Figure 2: Larkin Sentral’s waqf asset management.Source:

(Ramli & Mahmud, 2019) with adaptation.

Explanation:

1(a) – Larkin Sentral issued cash waqf shares and

the wāqif or donors subscribed to the shares.

1(b) – The donor/subscriber executed a declaration

for the purpose of endowing the subscribed shares to

WANCorp (Waqf hujjah). The effect of such

declaration is that the status of the normal shares

will be changed to waqf shares.

2 – 100% of the dividend declared by Larkin Sentral

will be transferred to WANCorp as the private

trustee cum beneficiaries to the waqf proceeds.

3 – From the 100% transferred to WANCorp, 90%

will be given back to Larkin Sentral for it to use for

charity purposes.

4 – The remaining 10% will be given to JIRC

whereby 5% will be kept by JIRC and the remaining

5% will be distributed for charity in education,

entrepreneurship and health sectors.

Another best practice of Larkin Sentral is its

quarterly publication of report or statement that

details out the Larkin Sentral Project’s stage of

performance or delivery including the collection and

use of proceeds. As of May 2019, Larkin Sentral has

published four several statements or reports in the

form of advertisements in the local newspapers.

Their quarterly reporting gave an update of the

upgrading and refurbishment work of the Larkin

Sentral Project, the amount of proceeds raised from

the IPO and the corresponding use of proceeds on a

quarterly basis. An accounting firm is hired to study

and confirm the amount of revenue acquired and the

amount utilised before these information are made

available to the public (Kasri and Shukri, 2020).

This instil confidence in the public especially those

who subscribed the cash waqf shares and assurance

that the proceeds are utilised as per the commitment

given in the Larkin Sentral’s prospectus.

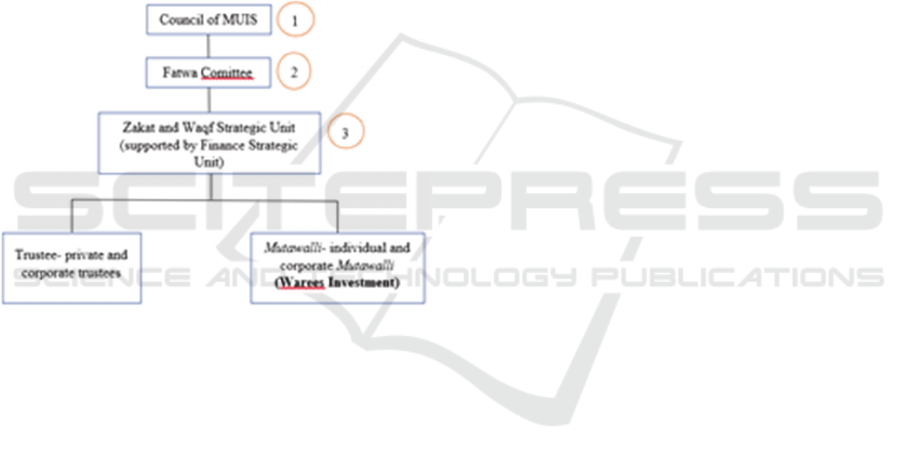

In Singapore, MUIS oversees the awqaf

administration and overall compliance which

7th AICIF 2019 - ASEAN Universities Conference on Islamic Finance

222

includes taking charge of the overall decision-

making related to operational plans and policies.

There are three types of waqf administrators

supervised by MUIS: (i) British and Malayan

Trustees - a public listed trust company which

manages some awqaf assets; (ii) private trustees -

individuals who manage and run awqaf set up for

particular families (mostly relatives or descendants

of the late wakif); and (iii) Warees Investments - a

wholly owned subsidiary of MUIS, that manages the

rest of the awqaf assets. While MUIS plays the

regulatory role and improves the corporate

governance of awqaf, the trustees and mutawallis

play the managerial role where they need to report

and seek approval from MUIS for any sale and

purchase of waqf assets. Diagram C exhibits the

governance structure of MUIS and Warees

Investment in waqf administration.

Figure 3: Waqf Administration Organizational Chart.

Source: (Abdul Aziz et al., 2019) with adaptation.

1. The Council of MUIS is the overall decision-

making body and is responsible for the

formulation of policies and operational plans.

The Council is made up of the President of

MUIS, the Mufti of Singapore, the Chief

Executive, as well as members recommended by

the Minister-in-Charge of Muslim Affairs and

nominated by Muslim organisations. All

members of the Council are appointed by the

President of the Republic of Singapore.

2. Shariah issues matter shall be heard by the Fatwa

committee. Any investments, purchases or

financial obligations or implications which

exceed the amount of SGD5,000,000 (USD

3,673,399) will need the Minister’s approval.

3. Zakat and Wakaf Strategic Unit of MUIS

oversees the whole compliance of waqf

management by the three types of Wakaf

administrators namely private trustees, corporate

trustees and Warees Investment.

In terms of reporting, Warees Investment reports

to MUIS on an annual basis of their activities and

financial. The reporting exercise is conducted within

the stipulated time in accordance with AMLA.

Having said that, it is observed that Warees

Investment annual report is not on its website. It is

assumed that their annual report is integrated

together with MUIS Annual Report. The assumption

is based on the statement in MUIS Annual Report

that stipulates that the financial statement reported

by MUIS includes waqf fund that are not directly

managed by MUIS (Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura,

2018). In the meantime Warees Investment

continuously make available on their website

updates of any latest company’s news, asset

development launches as well as other relevant key

market trend (Warees, 2019b).

In Indonesia, pesantren refers to the traditional

Islamic school where customarily, the highest

authority of pesantren remains with Kiyai (Islamic

scholar/expert) as Kyai and his family solely owned

the pesantren together with all its assets. Upon

Kyai’s death, the pesantren and all its assets are then

bequeathed to his next generation. This hegemony

system has attracted a number of criticisms.

Masruchin (2014a) argued that this system inherit a

number of disadvantages, among them:

1. Not all families members can comprehend

inherent issues in pesantren. At the same time

family problems could inadvertently be dragged

into pesantren internal issues.

2. The lack of ownership of those who are not part

of Kyai and his family could make them feel not

part of the pondok but mere helper to the

pesantren.

3. There were instances where family members of

Kiyai who have been selected to lead pesantren,

do not have the required qualification. This

factor unfailingly led to the retreat and collapse

of a pesantren.

In fact, Gontor Lama was faced with these

issues. Trimurti (Kyai Ahmad Sahal, Kyai

Zainuddin Fannani and Kyai Imam Zarkasyi)

(Dacholfany, 2015) revolutionise the pesantren

hegemony system by endowing (waqf) their

pesantren ownership to the Muslim community. The

effect of this revolutionary action is that the

pesantren is no longer under the responsibility of

Kyai and his family but the Muslim community.

This differentiate them with other pesantren

(Aswirna, Fahmi, Sabri, & Yusna, 2018). The

Social Enterprise and Waqf: An Alternative Sustainable Vehicle for Islamic Social Finance

223

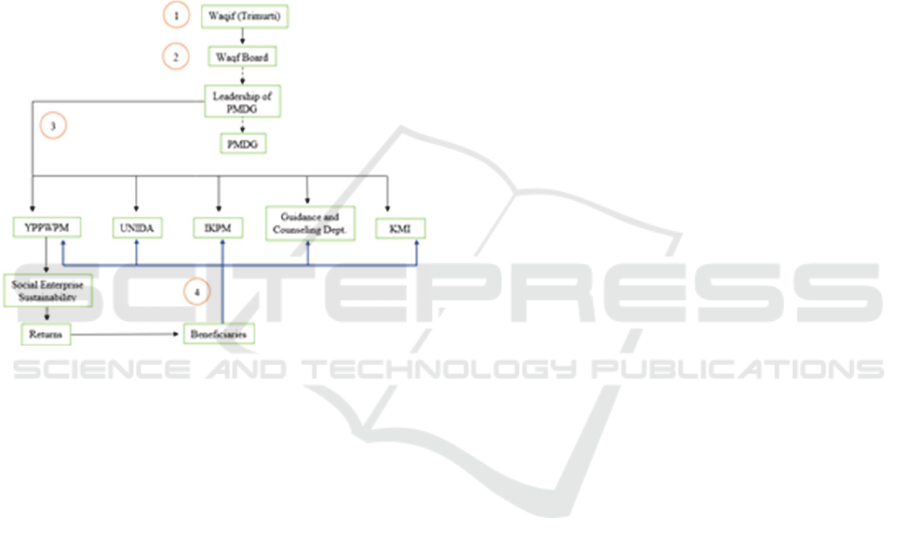

modernization impacted not only the management

but its education and teaching system. The main

authority now belongs to a Waqf Board. The Waqf

Board acts as the nazir (trustee) to carry out duties

towards their waqif (beneficiaries) and the Board

members being elected every five years. The daily

administrative duties and obligations are carried out

by the leaders in Pondok Gontor. They are the senior

teachers who devoted themselves in serving the

pesantren with the help of junior teachers (Muzarie,

2010). They too are chosen by waqf board and

elected for every five years (Masruchin, 2014a).

Diagram C describes the ‘modernised’ governance

structure of Pondok Gontor.

Figure 4: Governance structure of Pondok Gontor. Source:

(Siahaan, Iswati, & Zarkasyi, 2019) with adaptation.

1. Waqif or founder of the Trimurti handed over all

land assets along with the educational facilities

and infrastructure to the Gontor Waqf Board

which has 15 members;

2. The Waqf Board accepted waqf from the Waqif

and managed and developed Gontor boarding

schools. Its obligation is to execute the waqf

mandate - to develop pesantren into a quality and

meaningful Islamic university.

3. Islamic boarding school leaders form five

institutions, where each institution undertakes

separate and independent task but share the same

goal,which is to help the Waqf Board and its

leadership to realize the waqf mandate. The

University of Darussalam (UNIDA), Ikatan

Keluarga Pondok Modern (IKPM), Lembaga

Pengasuhan Santri and Kulliyatul Mu'allimin /

Mu'allimat Al-Islamiyyah (KMI) play the role of

regulating, pursuing and running the field of

education.

4. Yayasan Pemeliharaan dan Perluasan Wakaf

Pondok Modern (YPPWPM) is an extension of

the boarding school leadership that is being

tasked with managing and developing waqf

assets. The waqf assets centred around

plantation, agriculture, livestock, services, trade,

and industry.

3.1.3 Sustainable Business Model

BRAC, Larkin Sentral, Warees Investment and

Pondok Gontor are all sustaining themselves by

actively operating sustainable business models.

Some have massive capacity and capability that

enables them to diversify their business. This

effectively allows them to benefit from economy of

scale activities, cross-subsidies and natural hedging

mechanism implementation.

BRAC’s social enterprises have facilitated the

poor to overcome two major challenges - sustainable

livelihood and market access. These major

concerns, if left unattended, would hinder economic

growth and social empowerment of the marginalised

communities. BRAC’s model of social enterprise

leverage on traditional non-profit activities with

business initiatives. The surpluses generated from

the social enterprise business is reinvested back into

BRAC’s development projects that would further

accelerate social impact (BRAC, 2018).

BRAC’s social enterprise activities centred

around agriculture and livestock commercial

initiatives that enable the community to achieve and

sustain food security. It developed value chains for

individuals, microentrepreneurs, smallholder farmers

and producers by combining capacity building and

extension services, and linking them to markets for

sustainability. The followings are the social business

ventures that BRAC has undertaken as of 2018

(BRAC, 2018):

1. Aarong

Aarong is said to be one of the country’s largest and

most popular retail chains, with 3 sub-brands -

HerStory, Taaga, and Taaga Man that catered to

different market segments. The business of Aarong

has harnessed the skills of 65,000 artisans across

Bangladesh through a vast network of rural

production centres and independent producers.

2. BRAC’s Artificial Insemination

It provides insemination services to over 680,000

cattle farmers to boost the productivity of their

livestock and optimise their gains as a result of

higher-quality cow breeds. BRAC Artificial

Insemination offers its services through 2,600

trained service providers across the country.

7th AICIF 2019 - ASEAN Universities Conference on Islamic Finance

224

3. BRAC Chicken

It processes and supplies high-quality dressed

chicken and value-added frozen food products to a

range of clients, from restaurants to retailers. BRAC

Chicken processes around 8 metric tonnes of raw

chicken and 2 metric tonnes of ready-to-cook frozen

products every day.

4. BRAC Cold Storage

It operates chill storage facilities for harvested yields

of potato farmers to ensure that their products are

kept fresh. BRAC Cold Storage also integrates

farmers with the potato processing industry.

5. BRAC Diary

It provides a range of high-quality dairy products for

urban consumers. BRAC Dairy is the third-largest

milk processor in the country, collecting and

processing on average 130,000 litres of milk every

day. It also ensures fair prices and greater market

access for over 50,000 dairy farmers across

Bangladesh.

6. BRAC Fisheries

It pioneered commercial aquaculture in Bangladesh

and leverages on Bangladesh’s water bodies to boost

national fish production. BRAC Fisheries is one of

the leading suppliers of fish spawn, prawn larvae,

and fingerlings. It also supplies fish food, operating

10 hatcheries across 7 locations nationwide.

7. BRAC Nursery

It provides access to high-quality seedlings in order

to promote tree plantation across the country. BRAC

Nursery has been awarded first prize in the National

Tree Fair’s NGO Category for the last 12 years. It

operates 15 nurseries that are located across

Bangladesh.

8. BRAC Printing Pack

It provides flexible packaging material for food

items, processed edibles, and agricultural inputs.

BRAC Printing Pack produces around 1,200 metric

tonnes of packaging materials per year.

9. BRAC’s Recycled Handmade Paper

It recycles waste paper to make paper and paper

products such as envelopes, gift boxes and photo

frames. BRAC Recycled Handmade Paper recycles

approximately 70 metric tonnes of waste paper in a

year.

10. BRAC’s Salt

It provides a steady supply of iodised salt to help

curb iodine deficiency of the rural population across

the country. BRAC Salt has abled to reach

approximately 1.5 million people through 380 salt

dealers and around 40,000 community health

workers.

11. BRAC’s Seeds and Agro

It produces and markets high-quality maize, potato,

rice and vegetable seeds through an extensive

network of farmers, dealers, and retailers across

Bangladesh. BRAC Seed and Agro is the largest

private sector seed producer in the country, with 20

production centres and have employed 7,000

contract farmers.

12. BRAC’s Sanitary Napkin and Delivery Kit

It produces over 1.2 million safe and affordable

sanitary napkins to allow suburban and rural women

to attend work and school regularly. It also generates

more than 73,000 delivery kits to facilitate safer

births. BRAC Sanitary Napkin and Delivery Kit has

created income-generating opportunities for almost

40,000 community health workers.

13. BRAC Silk

It promotes silk production through its 19 production

centres across Bangladesh by guiding rural women

on the silk-making process. BRAC Silk promotes

traditional silk reeling and spinning practices by

supporting 3,700 women to engage in individual

‘charka’ spinning within their homes. It has

produced 900,000 yards of silk every year, which

are sold through Aarong and trade fairs.

As mentioned earlier, Larkin Sentral issued cash

waqf shares to the Malaysian market. The offering

aimed to raise RM85millions (USD21.25 million)

for its Larkin Sentral Project. Larkin Sentral project

consists of two phases. First is the upgrading and

refurbishment of Larkin Sentral which involves

upgrading the wet market and transport terminals as

well as refurbishing shop lots. While the second

phase includes the purchase of a piece of land,

adjacent to the terminal and to develop on it a 7

storey parking lot building. 42.6% from the

RM85millions (USD21.25 million) will be allocated

for the first phase and another 53.6% is allocated for

the second phase. The remaining 3.5% is to cover

the cost incurred in the public offering exercise

(Kasri and Shukri, 2020).

It was reported that at the closure of Larkin

Sentral’s public offering in May 2019, it has raised

from the public about RM7.861 million (USD 1.97

million) out of RM85 million (USD 21.25 million) it

planned to raise from its IPO exercise. Despite the

meagre amount raised, the IPO exercise is seen as an

important milestone in the development of

innovative asset class for waqf sector. To facilitate

the completion of the Larkin Sentral Project, Larkin

Sentral applied and obtained financing for the

project. The approval of the financing could be due

to the creditworthiness of Larkin Sentral’s parent

Social Enterprise and Waqf: An Alternative Sustainable Vehicle for Islamic Social Finance

225

company, JCorp which is the State of Johor’s

investment corporation (Kasri and Shukri, 2020).

The Larkin Sentral Project is expected to garner

steady and continuous income from the rental of the

terminal bus, retail lots including the wet market and

the parking. Currently, Larkin Sentral is one of the

largest transportation terminals in Malaysia which

attracted about 9 million visitors yearly or on

average 26,000 visitors daily. It has direct bus

services to and from various cities and towns in

Peninsular Malaysia as well as Singapore and Hat

Yai, Thailand. The installation of new e-ticketing

system ticket, with waiting area equipped with air-

conditioners together with QR Code system installed

at the passenger entrances, made the bus terminal

very convenient to all walks of life. Thus the

upgrading and refurbishment work that Larkin

Sentral is undertaking would bring more comfort to

the users in using the facilities and indirectly

increase the number of users and business to the

retailers (Kasri and Shukri, 2020).

Being MUIS’s waqf investment management

company, Warees Investment receives commissions

for the services it renders based on the gross income

of a waqf project. This incentivizes Warees to

maximize its returns (Abdul Aziz et al., 2019). To

do so, Warees Investment developed and deployed a

number of investment initiatives. The most popular

one was the Musharakah Sukuk for waqf asset

project located at Bencoolen Street in 2002 that need

a total funding of SGD35 million (USD25 million)

to undertake its development. The development

includes a mixed complex comprising of a mosque,

a commercial complex and 103 rooms of service

apartments. The development structure involved the

joint venture contract between MUIS (Baitulmal),

Warees Investment and waqf fund. The project

generated income from the lease of the retail units in

the commercial complex as well as the service

apartments (Abdullah & Saiti, 2016).

Warees Investment specializes in asset

regeneration and enhancement introduced through

its Wakaf Revitalisation Scheme (MRS). To further

boost the successful implementation of MRS,

Warees Investment initiated new financing

instrument 31. This new financing transforms and

sustains asset growth within the community. This

financing method will be the primary model in

realising the MRS project (Warees, 2019c). The

initial project under MRS is the Red House

development. Six properties – 5 shophouses and the

iconic Red House bequeathed to Wakaf Sheriffa

Zain Alsharoff Alsagoff – along East Coast Road

will be redeveloped into an integrated heritage

development. These assets are maximised into 42

residential units in 3 different classes, 5 retail

shophouses, 1 bakery and 1 open gallery. Such

development ensures better returns for the wakaf

which is aimed at establishing, maintaining and

upkeeping a dispensary (Warees, 2019a).

The future second project under WRS is Alias

Villas. Previously, there were only two dilapidated

village houses on the land belonging to Wakaf Al-

Huda which generate minimal returns to the wakaf.

With the WRS scheme, prestigious semi-detached

strata cluster housing development will be

constructed which will unlock the value of the asset.

The return will then be channeled to the wakaf sole

beneficiary, Masjid Al-Huda (Warees, 2019a). The

implementation of WRS enables waqf

properties/assets to generate a more steady and

sustainable income stream to the waqf beneficiaries

and Warees Investment indirectly.

Pondok Gontor has able to survive and sustain

due to its sustainable waqf management system

(Siahaan et al., 2019). Its waqf enlargement and

economic enterprise initiatives in particular has

enabled it to self-sustaining where surpluses made is

channelled to its educational and operational

purposes (Abdul Razak, 2016). Among the activities

are as follows:

(1) Development of La Tansa Kopontren Business

Units.

Pondok Gontor established an institution called

Yayasan Pemeliharaan dan Perluasan Wakaf Pondok

Modern (YPPWPM) to administer and develop

Pondok Gontor’s waqf properties/assets. YPPWPM

then formed an economic movement by opening

business units/ activities in the real sector under the

establishment of Kopontren (Masruchin, 2014).

Kopotren operates 32 units of economic activities

with the total profit of Rp 124 billion (USD 8.8

million) per year which have benefited its Islamic

boarding schools, santri (students) and the wider

community. Diagram D enumerates Kopotren

economic activities.

(2) Waqf Land Management System.

Sawah (plantation) lands are managed by YPPWPM

by planting crops food such as rice, corn and

secondary crops. In managing these lands,

YPPWPM is facilitated by a supervisor called the

nazir. These lands are managed in three ways

(Masruchin, 2014b):

1. In the form of Mukhabarah Agreement. where

tanah sawah (padi field) is managed by the

farmers and the profit-sharing ratio is determined

at the inception of the contract, based on the

7th AICIF 2019 - ASEAN Universities Conference on Islamic Finance

226

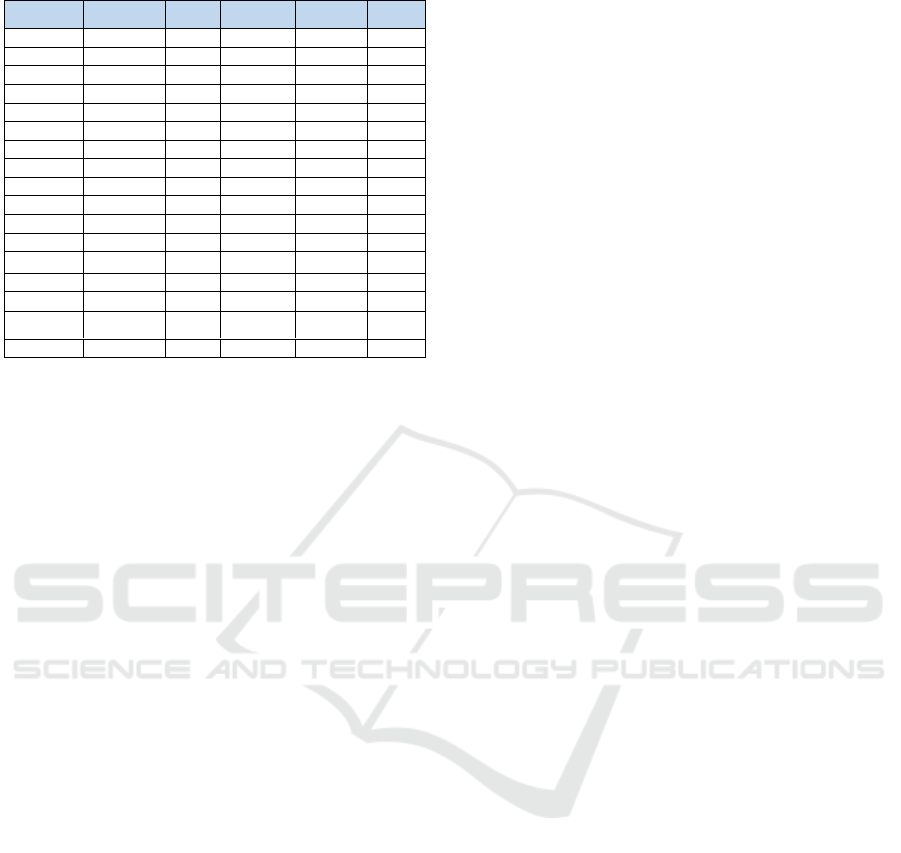

Table 1: Economic activities under Kopotren.

Source: (Siahaan et al., 2019).

agreement between the farmers and YPPWPM.

The profit distribution between farmers to

YPPWPM is 40:60.

2. In the form of Ijarah Agreement where the waqf

land is leased to the farmers and the farmers paid

the rental according to the crop season.

3. In the form of rent which depends on the results

of the plantation. The lessee will pay according

to the amount of proceeds obtained.

The waqf lands covers 320 hectares and they

continue to grow. Today 212 hectares of rice fields

are harvested twice a year and have yielded Rp726

million rupiahs (USD 51,678) (Nur, S., 2019).

3.1.4 Socio-economic Impact

The social impact made by these four entities is

tremendous considering their self-sustaining models

and the end benefit that society and environment

have enjoyed.

In addition to the job creations created and

capacity building developed through BRAC’s social

enterprises, BRAC has also made significant social

impacts in its other programs. Among them are

BRAC’s Ultra-Poor Graduation Program and

Microfinance that have made positive social impact

locally and abroad as follows (BRAC, 2018):

i- 12.9% of the Bangladesh population lives in

extreme poverty. It was reported in 2018 that via

BRAC’s Ultra-Poor Graduation Program, a total of

114,528 ultra-poor households have been enrolled

into this program. Out of which 43,682 households

from the 2017 cohort graduated from ultra-poverty

in 2018. Since its implementation in 2002, a total of

1.9 million households have emancipated from the

cycle of ultra poverty and have played active roles in

the market economy. The exemplary model of this

program has been replicated by NGOs, governments

and multilaterals from over 43 countries for example

Uganda, Kenya, Lesotho, Philippines, Liberia, Egypt

and Rwanda.

ii- 50% of adults in Bangladesh do not have

access to formal financial services. Through

BRAC’s Microfinance, as of 2018, USD4 billion

have been disbursed to 7.1 million clients of which

87% of its clients are women. Out of 7.1 million

clients, 5.6 million are given loans and 84% thereof

are given insurance coverage. By 2018, a total

amount of USD828 million has been kept on saving.

As part of its customers’ protection, BRAC has put

in place 2,100 customer service assistants in all its

branches nationwide. They act as the first point of

contact to attend to any queries and concerns by the

customers as well as providing these customers pre-

disbursement financial literacy training. This reflects

BRAC’s responsible financing policy and practice.

BRAC has also offered Microfinancing to the poor

outside Bangladesh. In 2018, a total of USD 247.98

million in loans have been disbursed to 571,935

borrowers in Myanmar, Tanzania, Liberia, Sierra

Leone and Uganda.

The idea of issuing Larkin Sentral cash waqf

shares publicly is due to the change in the corporate

approach of WANCorp from being exclusive to

inclusive. The IPO allows the public to participate in

its waqf activities. Larkin Sentral Terminal is a

rundown building where bus tickets are sold at the

terminal counter with no availability of online

ticketing system. The upgrading of the terminal is

direly in need as it will cater for the lower and

middle income people who travel within the country

and to the neighboring countries. The upgrading and

refurbishment of the terminal provides ample

parking space and online ticketing system as well as

better retail facilities (Securities Commision, 2018).

A total of twenty retail lots worth RM1.3 million

(USD 310,712) were distributed to 20 recipients

consisting of single mothers, the disadvantaged and

the disabled (Dua puluh individu B40 ditawar

premis perniagaan di Larkin Sentral, 2019). The

100-square-foot bazaar lot which is equipped with

water and electricity supply facilities, given to each

recipient, are fully funded through the Larkin Sentral

cash waqf shares. Eligible tenants are given a five

year lease term of RM400 per month and among the

businesses available in the lot are food, beauty and

handicraft products (Hussein, I.N.A., 2019).

Guidance and assistance will be provided from time

to time to ensure these recipients are self-sufficient

and ultimately able to run their own business on the

Unit business Profit

(in Rp)

Profit

(in USD)

Unit business Profit

(in Rp)

Profit

(in USD)

Printin

g

12,764,597,063 906,877 Baker

y

1,514,020,100 107,520

Book store 12,544,965,417 891,273 Pharmac

y

1,899,587,100 134,901

Mantin

g

an DC 17,515,221,000 1,244,392 Mineral water 2,094,132,934 148,738

Sport store 10,163,278,298 721,759 Gambia telephone 493,282,900 35,036

Confectionar

y

3,631,733,900 257,949 Roya 4,347,238,909 308,700

Building materials 20,521,212,500 1,457,598 Laundr

y

233,303,500 16,567

Al-Azhar telephone 1,206,540,000 85,699 Grocer

y

1,042,473,250 74,026

Sele

p

9,735,926,882 691,531 Latansa DC 4,124,585,000 292,919

Latansa tele

p

hone 2,243,245,000 691,531 Restauran

t

1,295,039,000 91,970

Trans

p

ortatio

n

664,657,750 47,211 Chicken slau

g

hter 1,592,778,500 113,115

Guesthouse IKPM 462,935,000 32,883 Chicken noodle 235,209,764 16,704

Azhar canteen 1,703,236,700 120,985 La-Tansa tea 235,541,000 16,727

Guesthouse 711,591,443 50,546 Ice cream 277,177,600 19,681

Asia photocop

y

1,070,349,000 76,029 Computer centre 321,443,912 22,824

UKK Mini Market 8,059,056,103 572,454 TPS 140,301,000 9962

KUK Convenience

Store

1,612,988,375 114,539 Catfish 58,232,000 4135

Total 104,611,534,431 7,429,071 Total 19,904,346,469 1,413,523

Social Enterprise and Waqf: An Alternative Sustainable Vehicle for Islamic Social Finance

227

premises of their choice (Dua puluh individu B40

ditawar premis perniagaan di Larkin Sentral, 2019).

In addition to the above, 90% of dividends

received by WANCorp from the Larkin Sentral cash

waqf will be used for the following charitable

purposes:

1. Reasonable rental rate (by lowering the rental

rate by up to 10% over the normal market rental

rate) is imposed to selected Larkin Sentral tenants

(excluding tenants with a stable business), subject to

timely rental payment performance records; and

2. Minimum rental rates for small shop lots

created in Larkin Sentral for single mothers and low-

income groups (which could be reduced to half the

market rate per square feet).

While the balance of 10% dividend received by

Johor Islamic Religious Council from the Larkin

Sentral cash waqf will be used for itself as well as to

be distributed for charity in education,

entrepreneurship and health sectors (Waqaf Saham

Larkin Sentral, 2019).

As of 2019, MUIS has been disbursing more

than SGD4 million (USD2.9 million) to various

waqf beneficiaries which includes mosques,

madrasahs (Islamic schools) and Muslim

organisations that strive to benefit the local

community and its well-being. Out of which,

SGD1.8 million (USD1.3 million) is channelled to

32 local mosques to aid in funding their upgrading

projects and mosque programmes for the purpose of

benefiting the community. Additional SGD400,000

(USD 293,968) is disbursed to 6 full-time madrasahs

and part-time mosque-based madrasahs. Madrasah

play an important role in nurturing future religious

leaders in the community and these funds will assist

the madrasahs in developing programmes as well as

upgrading their facilities to provide a more

conducive learning environment. While

SGD380,000 (USD 279,270) is disbursed to 30

Muslim and Voluntary Welfare Organisations to

help support social initiatives and religious

programmes for the community. These include

welfare homes that shelter persons facing difficult

family or personal circumstances; food banks which

provide food supplies and rations to the poor and

needy; youth-focused organisations as well as

welfare organisations that provide services to those

who struggle with mental illness, women facing

injustice and cancer patients (Masood, 2019).

Pondok Gontor have health centers in each of its

pondok. However, the health centers offer limited

services and cater only for its students. Pondok

Gontor decided to build a public hospital that would

cater for the general public. The people of Ponorogo

in the Mlarak region can then take advantage of the

service offered by this public hospital. The plan is to

build a three floor hospital with 100 beds. The

construction of the hospital has reached 50%

completion which is expected to be in operation by

2021. The budget for the construction of the hospital

including the medical devices is estimated to reach

about Rp80 billion (USD5,681 billion). At the

moment, the budget is funded solely by Pondok

Gontor (Jalil. A., 2019).

Pondok Gontor also do trainings to empower the

local farmers, traders and small and medium (SME)

businesses. It guides them on many respects

particularly on growing their skills and mindset.

Among the trainings given are instilling trading

skills for traders and SMEs, and granting rice slips,

rice milling and facilities for the farmers as well as

the surrounding community (Kusumadewi, E. W.,

2016). Recently, Pondok Gontor entered into a

Memorandum of Understanding with Bukalapak, a

unicorn and one of the largest e-commerce

companies in Indonesia, to do digital

entrepreneurship training. The trainings are meant

for the trainees from Pondok Gontor-assisted SMEs

and Pondok Gontor alumni businesses to improve

their business. The collaboration allows the use of

Bukalapak online platform to market Pondok Gontor

stakeholders' digital products and its e-ticketing

technology for the collection of zakat funds, infaq

and other charitable activities (Undang CEO

Bukalapak, Pondok Gontor Rancang Ekonomi Umat

Berbasis Digital, 2019).

4 CONCLUSION AND

RECOMMENDATION

4.1 Conclusion

The four mini case studies deliberated in this paper

disclosed and highlighted the sustainable operating

model of these entities including their best practices,

governance, transparency and social impact. These

models have succeeded in sustaining these entities to

where they are today. However waqf institutions

have much to learn from the success story of

BRAC’s sustainability and transparency. BRAC

story demonstrated the importance of competent

management team, transparency in reporting,

disclosure and reliable database. This is important as

waqf institutions deals with public money and public

trust.

7th AICIF 2019 - ASEAN Universities Conference on Islamic Finance

228

4.2 Recommendation

In the meantime a number of recommendations can

be proposed for consideration by waqf entities as

well as waqf supervisory authorities namely:

1- Publication of annual report annually. Among its

key content are annual financial statement,

mobilization of the waqf proceeds and returns from

the investment, performance and delivery of the

waqf projects, assessment of the waqf performance

and effectiveness, and future plan to meet its

missions.

2- Asset allocation, investment policy and strategy

must be clearly stated and documented. The

management team must clearly stipulate the

apportionment that will go to cover the expenses of

the waqf project and investment. This includes the

operational and funding costs.

3- Qualified and competent professionals must be in

the team of management. Human capital must be

developed through theoretical and hands-on

trainings, workshops and internships programs.

4- Advanced technology like blockchain and smart

contract can be adopted to address the transparency

and accountability problems in the waqf

mobilisation and distribution structure. Through this

advanced technology, the delivery and progress of

the waqf project can be monitored on real time basis

and alleviate any intended abuse of power and funds

(Kasri and Shukri, 2020).

REFERENCES

Abdul Aziz, A. H., Zhang, W., Abdul Hamid, B.,

Mahomed, Z., Bouheraoua, S., Kasri, N. S., & Sano,

M. A.-A. (2019). Maximizing Social Impact Through

Waqf Solutions. Retrieved August 5, 2019, from

www.worldbank.org/en/country/malaysia

Abdullah, A., & Saiti, B. (2016). A re-examination of

musharakah bonds and Waqf development: The case

of Singapore. Intellectual Discourse, 24(January

2017), 541–562.

Abdul Razak, D., Che Embi, N.A., Che Mohd Salleh, M.,

& Fakhrunnas, F. (2016). A Study On Sources Of

Waqf Funds For Higher Education In Selected

Countries. Adam Akademi, 6(1), 113-128

Anheier, H. (n.d). What is The Third Sector. Retrieved

October 18, 2019 from http://fathom.lse.ac.uk/

Features/122549/.

Anwar, T. (2017). Waqf Endowment: AVehicle for Islamic

Social Entrepreneurship. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic

Banking and Finance Institute Malaysia

Aswirna, P., Fahmi, R., Sabri, A., & Yusna, D. (2018).

Paradigm Changes of Pesantren : Community Based

Islamic Scholar Perception About Post-Modernism

Pesantren Based on Android. 3(5), 31–38.

BRAC. (2018). BRAC Annual Report. 1(1), 108. Retrieved

October 13, 2019, from http://www.brac.net/

publications/annual-report/2018/

Dacholfany, M. I. (2015). Leadership Style in Character

Education at The Darussalam Gontor Islamic

Boarding. Al-Ulum, 15(2), 447. https://doi.org/

10.30603/ au.v15i2.212

Department Trade and Industry. (2002). Social enterprise:

a strategy for success. Retrieved August 10, 2019,

from http://www.dti.gov.uk/

Dua puluh individu B40 ditawar premis perniagaan di

Larkin Sentral (2019, January 31), BERNAMA.

Retrieved October 19, 2019, from

http://www.bernama.com/state-news/

beritabm.php?id=1690721

Fasa, M. I. (2017). Gontor as the Learning Contemporary

Islamic Institution Transformation Toward the

Modernity. HUNAFA: Jurnal Studia Islamika, 14(1),

141. https://doi.org/10.24239/jsi.v14i1.462.141-174

Hussein, I.N.A. (2019, February 1) OKU gigih berniaga

bantu keluarga. Harian Metro. Retrieved October 19,

2019, from https://www.hmetro.com.my/mutakhir/

2019/02/418553/oku-gigih-berniaga-bantu-keluarga

ILO Social Economy. (2010, February). Operationalising

the Action plan for the promotion of social economy

enterprises and organisations in Africa Toward A

Regional Programme on Social Economy in Africa.

Task Force Meeting at ITC ILO, Turin.

Jalil. A. (2019, October 8) Pondok Gontor Segera Miliki

Rumah Sakit Senilai Rp80 Miliar. Solopos.com.

Retrieved October 20, 2019, from

https://www.solopos.com/pondok-gontor-segera-

miliki-rumah-sakit-senilai-rp80-miliar-1023661.

Kasri, N. S & Shukri, M.H. (2020). International Best

Practices In Existing Corporate Waqf Models: A

Retrospective, Challenges And Impact Of Religious

Endowments On Global Economics And Finance. IGI

Global

Kusumadewi, E. W. (2016, January 24). Selalu Libatkan

Masyarakat Sekitar, Kunci Sukses Pesantren Gontor.

Merdeka.com. Retrieved October 20, 2019, from

https://www.merdeka.com/peristiwa/selalu-libatkan-

masyarakat-sekitar-kunci-sukses-pesantren-

gontor.html

Mahomed, Z. (2017). The Islamic Social Finance &

Investment Imperative. Centre For Islamic Asset and

Wealth Management, 29–31. Retrieved October 14,

2019, from http://www.inceif.org/archive/wp-

content/uploads/2018/04/The-Islamic-Social-Finance-

Investment-Imperative.pdf

Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura. (2018). Annual Report

MUIS. 258. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from

https://www.muis.gov.sg/-/media/Files/Corporate-Site/

Annual-Reports/Muis_AR_-2018.pdf

Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura. (2019). Admin &

Management of Wakaf by MUIS. Retrieved August 15,

2019, from https://www.muis.gov.sg/wakaf/About/

Administration-of-Wakaf

Social Enterprise and Waqf: An Alternative Sustainable Vehicle for Islamic Social Finance

229

Masood, E. (2019). Muis Wakaf Disbursement Ceremony.

Singapore: Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura.

Masruchin. (2014a). Bab III Profil Pondok Modern

Darussalam Gontor A Kemandirian Pondok Modern

Darussalam Gontor. Retrieved October 16, 2019,

from http://digilib.uinsby.ac.id/895/6/Bab 3.pdf

Masruchin. (2014b). Bab IV Hasil Analisis Data Dan

Pembahasan A. Analisa Pengelolaan Wakaf Produktif

di Pondok Modern Darussalam Gontor 1. Konsep

Wakaf Gontor. Retrieved October 16, 2019, from

http://digilib.uinsby.ac.id/895/9/Bab%204.pdf

Mohd Noor, A.H., Abdullah Sani,A. Ab Hasan, Z &

Misbahrudin, N.T. (2018). A Conceptual Framework

for Waqf-Based Social Business from the Persppective

of Maqasid Al-Shariah. International Journal Of

Academic Research In Business & Social Sciences,

8(8), 801-818

Muhamed, N.A., Hisham Kamarudin, M.I. & Nasrudin, N.

S. (2018). Positioning Islamic Social Enterprise (ISE).

Journal of emerging economies & Islamic Research

6(3), 28-38

Muzarie, M. (2010). Hukum Perwakafan dan Implikasinya

Terhadap Kesejahteraan Masyarakat: Implementasi

Wakaf di Pondok Modern Darussalam Gontor.

Jakarta, Indonesia: Kementerian Agama RI.

Nur, S. (2019, July 19). Ternyata Wakaf Kunci

Kemandirian Pesantren Gontor. Rumah Wakaf.

Retrieved October 21, 2019, from

https://www.rumahwakaf.org/ternyata-wakaf-kunci-

kemandirian-pesantren-gontor/

Pondok Modern Gontor Darussalam. (2019). Tentang

Gontor. Retrieved October 19, 2019, from

https://www.gontor.ac.id/pondok-modern-darussalam-

gontor-2#

Prospektus Larkin Sentral. (2017). Larkin Sentral

Property Berhad. Retrieved August 10, 2019, from

https://www.waqafsahamlarkin.com/prospectus.pdf

Ramli, R., & Mahmud, M. L. (2019). Waqaf Saham

Larkin Sentral: Pioneering Initial Public Offering Of

Waqf Shares. Islamic Finance Mini Pupillage

Programme, 167. Retrieved August 20, 2019, from

https://www.mia.org.my/v2/downloads/resources/publ

ications/2019/07/02/MIA_IF_Mini_Pupillage_Case_S

tudies_2019.pdf

Sadeq, A. M. (2002). Waqf, perpetual charity and poverty

alleviation. International Journal of Social Economics,

29(1–2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/

03068290210413038

Salarzehi, H., Armesh, H & Nikbin, D. (2010). Waqf As a

Social Entrepreneurship Model In Islam. International

Journal Of Business And Management, 5(7).

Securities Commision. (2018). Proceedings of the SC-

OCIS Roundtable 2018 (Vol. 53). https://doi.org/

10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Seelos, C., & Mair, J. (2006). BRAC – An Enabling

Structure For Social And Economic Development.

3(January), 28.

Sepulveda, L. (2015). Social Enterprise - A New

Phenomenon in the Field of Economic and Social

Welfare? Social Policy and Administration, 49(7),

842–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12106

Siahaan, D., Iswati, S., & Zarkasyi, A. F. (2019). Social

Enterprise: the Alternatives Financial Support for

Educational Institusion. International Journal of

Economics and Financial Issues, 9(3), 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.32479/ijefi.7626

Undang CEO Bukalapak, Pondok Gontor Rancang

Ekonomi Umat Berbasis Digital. (2019, June 16).

Brito. Id. Retrieved October 20, 2019, from

https://www.brito.id/undang-ceo-bukalapak-pondok-

gontor-rancang-ekonomi-umat-berbasis-digital

Warees. (2019a). Assets. Retrieved October 23, 2019,

from https://www.warees.sg/

Warees. (2019b). Home. Retrieved October 23, 2019, from

https://www.warees.sg/

Warees. (2019c). Wakaf Revitalisation Scheme (WRS).

Retrieved October 23, 2019, from

https://www.warees.sg/wakaf-revitalisation-scheme-

wrs/

Waqaf Saham Larkin Sentral. (2019). Soalan Lazim.

Retrieved October 23, 2019, From

https://www.waqafsahamlarkin.com/pages.aspx?Conte

nt_Name=Soalan_Lazim

7th AICIF 2019 - ASEAN Universities Conference on Islamic Finance

230