Pink Tide: Neo-developmentalism in Brazil and Argentina

Imelda Masni Juniaty Sianipar and Arthuur Jeverson Maya

Center for Social Justice and Global Responsibility (CSJGR) LPPM, Universitas Kristen Indonesia, Jakarta

Keywords: Pink Tide, Globalization, Class, Brazil, Argentina, The Market Left.

Abstract: This study aims to trace the pink tide model with the neo-developmentalism state in Brazil and Argentina.

The pink tide model in both countries seeks to unite the market and the state in the national economic

development so that welfare and social equality can be achieved. However, in practice, pink tide with social

equality discourse is not fully successful in the hands of the left leader, there is an increase in poverty and

social inequality. To uncover the problem in applying the pink tide model run by leftist leaders, this study

will use the concept of globalization by David Harvey and the term of class by Karl Marx qualitatively. This

study has two results. Firstly, globalization has a significant impact on the integration of the pink tide model

of development which based on the market and the state in Latin America. Secondly, class exploitation has

collectively led to the economic crisis in Brazil and Argentina.

1 BACKGROUND

It has become an expression of globalization that has

taken place in the last few decades is seen as having

a wide influence on the chances of economic

interdependence. The waning significance of

territorial borders and the increasing awareness of

the state as part of global economic development are

a small part of some new developments brought

about by globalization that have a positive effect on

the political economy. Of course, globalization does

not always bring good news and can mean

impoverishment, human rights violations and

environmental destruction for certain countries. But

the distanciation and time compression made

possible by, among other things, recent

developments in communication and transportation

technology make economic integration no longer a

completely normative idea. That is, economic

development across national borders is no longer

limited to hopes and ideals but is almost an

inevitable demand.

Economic globalization comes in two forms.

First, through a process based on the pressure of the

global economic system, with governance as the

keywords, including the International Monetary

Fund, World Trade Organization, and World Bank,

in which countries try to create free markets.

Second, through a process that is more domestic or

regional, in which countries experiencing economic

crisis try to carry out economic development through

alternative models other than the Washington

Consensus free-market version. Economic

globalization in Latin America comes through the

application of neoliberalism.

Neoliberal is an economic model that limits the

role of the state in economic activity. Neoliberal

wants an economic system based on individual

freedom without state interference in the market.

The main actor in the economic process is the

market, not the state. On this basis, it can be argued

that neoliberalism discredit the collectivity in the

way of production to get added value. This is

reflected in the massive investment from

Multinational Cooperation (MNC) in Latin America.

The application of neoliberalism did not bring

prosperity and justice as promised. It resulted the

economic and social crisis in Latin America. The

failure of economic development led to Latin

American regional social movements, namely the

anti-neoliberalism movement or referred to as the

Pink Tide(Loureiro, 2018). Pink Tide is a socialism

movement which is considered to be phenomenal in

Latin America. Pontoh said that the Latin American

community movement has two fundamental reasons,

namely the failure of left-wing communism

socialism led by the Soviet Union and economic

inequality because of the US neoliberal development

model (Pontoh, 2007).

Sianipar, I. and Maya, A.

Pink Tide: Neo-developmentalism in Brazil and Argentina.

DOI: 10.5220/0010001900230032

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Social and Political Development (ICOSOP 3 2019) - Social Engineering Governance for the People, Technology and Infrastructure in

Revolution Industry 4.0, pages 23-32

ISBN: 978-989-758-472-5

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

23

If neoliberalism offers social welfare and justice

through free markets, then Pink Tide offers a more

flexible model of mediating capitalist and labor class

relations through economic and social policies based

on negotiation procedures. Unfortunately, the Pink

Tide development framework did not last long

because its implementation could not address the

problems of the Latin American people but instead

created an economic crisis and social injustice. This

reinforces the statement that the neoliberalism and

Pink Tide are not perfect models.

The dynamics of the economic crisis in Latin

America give interesting attention to the study of

globalization. The destruction of space and time is

inevitable, this is evidenced when a country

experiences an economic crisis it will spread rapidly

to other countries as well. Territorial boundaries are

no longer a problem, the problem lies in capital

accumulation which focuses on added value. From a

capitalist point of view, added value can only be

carried out by workers' activities, so that workers

will be made as commodities that receive wages to

produce added value.

Capitalism in Latin America is characterized by a

combination of core capitalist sectors with

unregulated small scale commodity production. This

unregulated sector is called the informal urban

economy, including self-employed workers engaged

in subsystem activities and employees of

microbusinesses (Elbert, 2018). Capitalism has a

hope that the working class will be absorbed by the

core capitalists. However, the structural dynamics of

peripheral economics have instead produced dual

societies in which a large portion of the population

has never been fully incorporated into economic

capitalists.

Thus, the economic crisis that hit Latin America

including Brazil and Argentina is rooted in the

capitalist mode of production both in the application

of neoliberalism model and the Pink Tide model.

The way it develops and functions normally, each

branch of production does not directly receive the

surplus value generated by the labor that it employs.

It only accepts fractions of all values produced.

Whereas the capitalist receives more value from the

whole production to be redistributed. This is

collective class exploitation in Brazil and Argentina.

2 ECONOMIC GLOBALIZATION

IN LATIN AMERICA

The process of globalization in Latin America began

in the 1970s when Latin American regional societies

became conservative and nationalistic and did not

readily accept the rapid social and economic changes

that globalization requires (Theodore, 2015). This

results in efforts to adopt economic neoliberalism to

offset the economic globalization process that is

sweeping Latin America. To quote Theodore,

globalization is defined as the trend towards greater

economic, cultural, political, and technological

interdependence among national institutions and

economics (Theodore, 2015). According to Harvey,

globalization is the destruction of space and time,

where there is no longer a distance that separates the

interaction of global society. The development of

information technology has damaged the order of

time quickly. Harvey argues that capital is moving

faster than before, because capital production,

circulation, and exchange occur at an ever-

increasing pace, especially with the help of

sophisticated communication and transportation

technology. He also stressed that economic activity

is the main factor driving the globalization process

(Harvey, 1989).

Harvey's concept is reinforced by Manuel

Castells' opinion that globalization is a network of

production, culture, and power that is constantly

shaped by technological advances, which range from

communication technology to genetic engineering.

Unfortunately, globalization has become an

instrument of global capitalism collaborating in

shaping a capitalist economic system that

encourages market expansion to gain large added

value for countries that control the means of

production, thus impacting on the exploitation of the

working class in Latin America. Castells also

stressed that power no longer comes from the state

and companies, but through the flow of information

and codes that connect companies and countries in a

global system.

Since the globalization process, Latin America

has entered a period of low and fluctuating growth

with high inflation bursts. The recession in 2015 and

2016 has paralyzed the economic growth of Brazil

so that the country must make an economic contract

of 7%. Brazil's economic recovery seems very slow.

In 2017 and 2018, Brazil's economic growth rate

showed a very low by 1.1% per year (see Graph

1)(Gallas and Palumbo, 2019). In 2018, Argentina

was hit hard by a series of external and internal

factors including severe drought, global financial

volatility in emerging markets after an interest rate

adjustment by the Fed, and market perceptions about

the pace of fiscal reform. The country announced a

program with an International Monetary Fund (IMF)

valued at US $ 57 billion, intending to stabilize

ICOSOP 3 2019 - International Conference on Social Political Development (ICOSOP) 3

24

public accounts to achieve primary fiscal balance by

the end of 2019. Argentina is currently in a

precarious economic balance. Significant

devaluation of the peso occurred in 2019, annual

inflation was more than 50% and GDP contracted

2.5% in 2018, and another 2.5% in the first half of

2019 (World Bank, 2019).

Graph 1: Brazil real GDP percentage growth (Gallas &

Palumbo, 2019).

Economic globalization has had a significant

impact on the regional economic integration of Latin

America, but it is more indicative of a decline in

economic growth, especially in Brazil and

Argentina. This is closely related to the regional

movement called the Pink Tide movement. This

regional phenomenon responds to the economic

globalization of neoliberalism in Latin America.

Argentina's presidential elections in 2015 and Brazil

in 2018, represent a change in populism toward

more orthodox economic policies. This shift is not

only in the economic structure, but also reflects

other fundamental changes such as increasing

population dissatisfaction with issues regarding

weak security and increasing corruption in political

institutions. Nevertheless, the market still plays an

important role in the political economy in Brazil and

Argentina.

Populism government in Brazil and Argentina is

the impact of the Pink Tide movement on

government dissatisfaction that adheres to the global

capitalist system. Nevertheless, the success or failure

of economic policy is closely related to political

development. In this regard, Brazil and Argentina

face macroeconomic challenges under the

parliamentary minority; a situation that is common

to many countries in the region today. As mentioned

by the Center for Global Development (Calvo et al.,

2018) that:

Economies highly integrated into the international

capital markets, with macroeconomic imbalances

inherited from populist governments, face a

particularly difficult challenge. On the one hand,

the required fiscal tightening entails the execution

of policies that may result in greater social unrest,

thus encouraging a gradual approach. On the other

hand, a gradual approach requires a greater

funding stream of financial funds thus exposing

the economy to higher financial risk. The dilemma

of choosing between a shock adjustment and a

gradual approach has been central to

understanding what has happened in Argentina

and is essential to assessing the options available

to the next government in Brazil.

The above challenges are supported by global

economic growth. Based on recent developments,

external challenges in Latin America will increase in

2019 due to slowing global growth. Since 2018

global economic growth has declined, including in

regions such as the United States, Europe, and

China. Global economic growth is predicted to

decline by 3.5% in 2019, compared to 3.8% in 2018

and 2017. This has an impact on declining global

demand and oversupply. In 2018, oil prices fell by

35%. Economic globalization integrates the global

economy so that the global economic downturn will

affect the economic growth of Brazil and Argentina.

The Pink Tide development model with the

character of developmentalism state in Brazil and

Argentina does not contribute to social welfare and

justice in both countries. This is similar to the

situation in Venezuela and Bolivia. Thus, it can be

argued that the Pink Tide model that gave birth to

the character of developmentalism state distorts

classic left to the contemporary left. Where the

contemporary left spectrum in Latin America with

the character of the Developmetalism state creates

two concepts namely the market left and the state

left. The characteristics of the state left are evident in

populist governments in Venezuela and Bolivia

including expanding the role of the state,

expropriation of foreign investment, and distribution

state power. While the character of the market left

can be seen in the formulation of Pink Tide's

populist government policies in Brazil and

Argentina in which the market is still dominated by

the global octopus such as IMF, WTO, and WB. It

also prioritizes international trade oriented on MNC

actors, and the control of energy resources by the

private sector. As a result of the implementation of

the neodevelopmentalism state with the character of

the market left in Brazil and Argentina, the

circulation of capital in the two countries provides

more working class services to the capitalist central

countries accessing the means of production, thereby

creating class exploitation in Brazil and Argentina.

Pink Tide: Neo-developmentalism in Brazil and Argentina

25

3 CLASS EXPLOITATION IN

BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA

Karl Marx in Das Kapital Volume 2 writes that all

the production of commodities is at the same time

the exploitation of labor-power; but only the

production of capitalist commodities is a historic

mode of exploitation, which in the process of

historical development revolutionizes the entire

economic structure of society by organizing its

gigantic work processes and technical expansion,

and soaring unmatched above all previous periods

(Marx, 2007a). Nevertheless, Economic

globalization forced Brazil and Argentina to adopt a

giant capitalist system which always had relations of

exploitation of the working class.

Furthermore Marx also states that the expansion

of the scale of production could be carried out in

relatively small quantities if one part of surplus

value was used for improvements that merely

increased the productive forces of labor used or

allowed it to simultaneously be exploited more

intensively. Alternately, when the working day is not

limited by law, an additional expenditure of

circulating capital (in the materials of production

and wages) allows an expansion of the scale of

production without any increase in fixed capital,

because the time spent is only extended, while the

turnover period was shortened accordingly (Marx,

2007a).

In Das Kapital Volume 3, Marx writes that a

capitalist mode of production that develops fully and

functions normally, each branch of production does

not directly receive the surplus value produced by

labor. It only receives a fraction, of all the values

produced, in proportion to the fraction it represents

from all capital used. The surplus value of a

particular bourgeois society as a whole is

redistributed. This results in an average rate of profit

that is more or less valid for each branch of capital.

Thus, each capital receives a share of all surplus

value produced by productive labor which is

proportional to its own share in all community

capital. This is the material basis of the common

interests of all capital owners in exploiting work -

which thus takes the form of collective class

exploitation (Marx, 2007b). The practice of

collective exploitation of class is still attached to the

policy of "market left" in Brazil and Argentina.

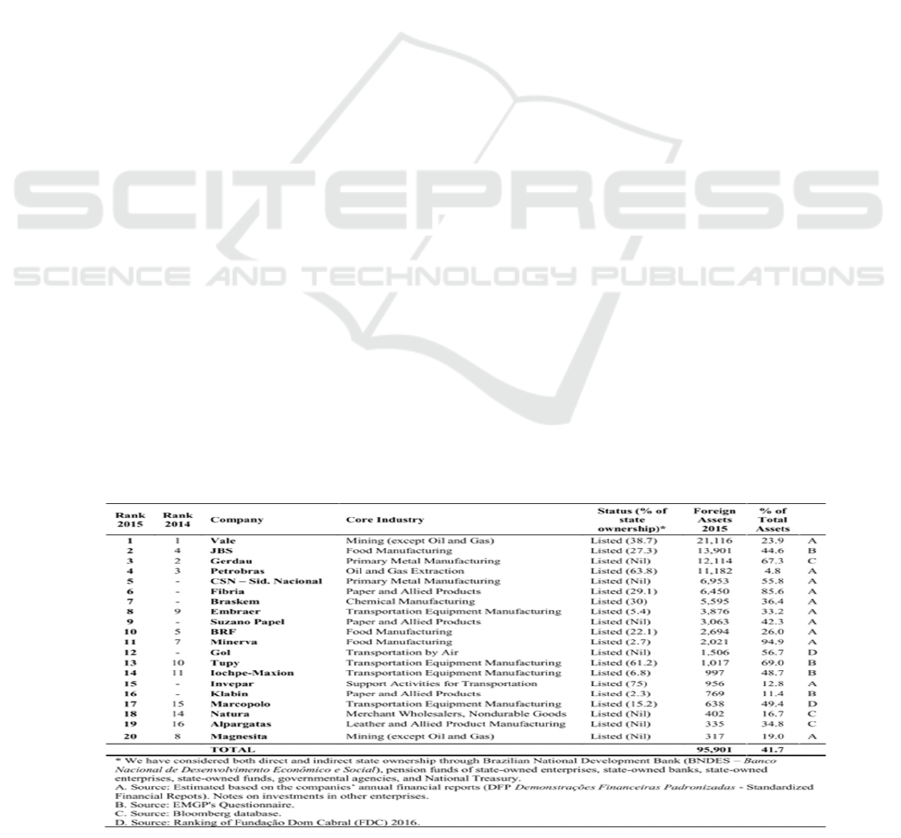

Out of Brazil's Top 20 multinational enterprises

(MNEs), mining, oil and gas extraction, primary

metal manufacturing, food manufacturing, paper,

and industrial products together, more than 84%

come from foreign assets (eleven companies). Four

companies including Vale, JBS, Gerdau and

Petrobras contributed more than 60% of the total

foreign assets of 20 Brazilian MNEs in 2015. Top-

ranking foreign investments from Brazilian MNEs

are (1) United States - 17 out of 20 companies; (2)

Argentina - 14 of the top 20 companies; (3) China -

11 of the top 20 companies. The foreign investment

is engaged in production and manufacturing, as well

as foreign sales and distribution centers (see Table

1) (Sheng and Junior, 2017). In the context of the

overall economic and political crisis in Brazil since

2014, divestment has become a strategic topic on the

agenda of many Brazilian companies during 2015.

Petrobras, for example, announced a massive

divestment plan. According to its annual report, the

company divested US $ 15.1 billion in 2015-2016

(in 2015 Petrobras divested US $ 0.7 billion) and

divested US $ 19.5 billion in 2017-2018 (Sheng and

Junior, 2017).

Table 1: Brazil: The top 20 non-financial multinationals, by foreign assets 2015 (USD Million)

(Sheng and Junior, 2017).

ICOSOP 3 2019 - International Conference on Social Political Development (ICOSOP) 3

26

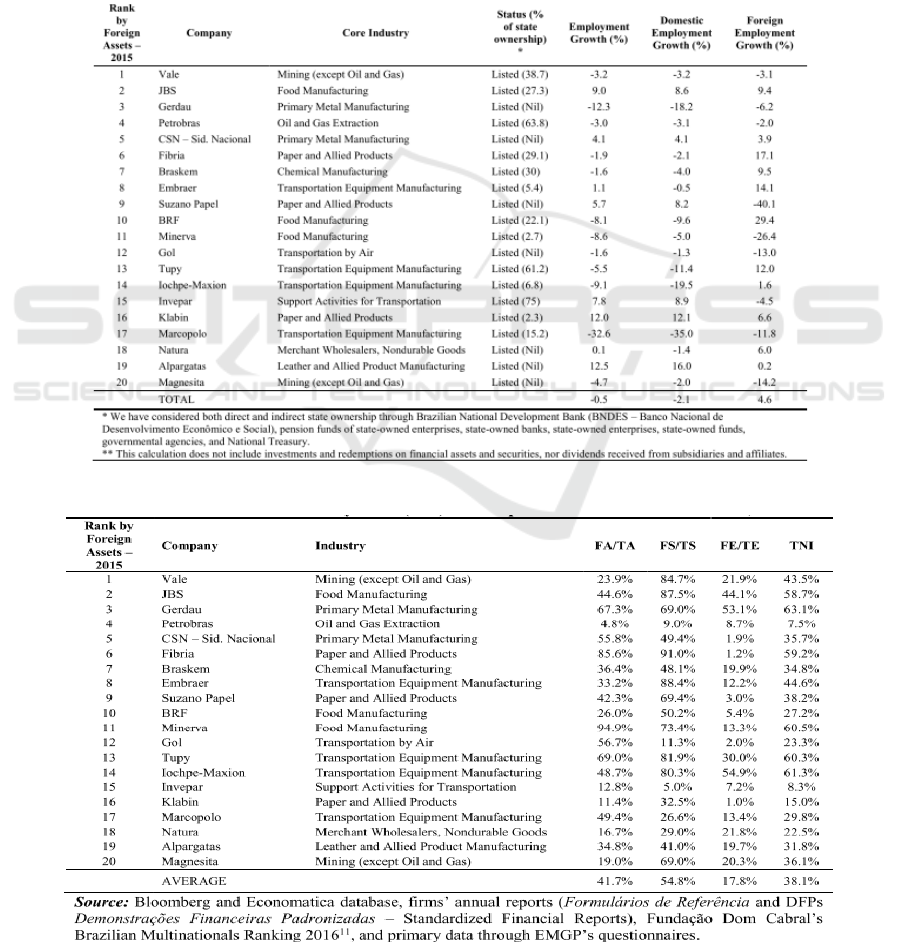

In 2015, the 20 Brazilian multinational

companies above had a combined total of 174,448

employees, excluding outsourced, temporary and

seasonal employees from abroad, representing a

13% reduction compared to 2014 of 201,343

employees from outside Brazil. According to the

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics

(IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e

Estatística), Brazil's domestic unemployment rate in

2015 was 8.5%, compared to 6.8% in 2014. IBGE

also estimates that the number of unemployed

workers in 2015 was 8.6 million, representing a 27%

increase from 2014. The unemployment rate is very

prominent in the manufacturing sector (see Table 2).

Besides, the average index of transnational

companies in 2015, the ratio of foreign assets to total

assets, foreign employment to total employment, and

foreign sales to total sales, measured from 20

Brazilian multinational companies is 38%. The

Gerdau company has the highest percentage of 63%

(see Table 3).

Table 2: Top 20 Brazilian MNEs employment in 2015 (Sheng and Junior, 2017).

Table 3: Transnationality Index (TNI) of the top 20 non-financial multinationals 2015 (Sheng and Junior, 2017).

Pink Tide: Neo-developmentalism in Brazil and Argentina

27

Brazil did impressive poverty reduction and

inequality between 2004 and 2014 as a result of

rapid formal employment growth, higher real wages,

and redistributive social assistance programs such as

Bolsa Família. With labor income as the main source

of income for poor and vulnerable households, the

current economic crisis poses a serious threat to the

sustainability of results in poverty and reduction of

inequality. As in the 2008-2009 financial crisis,

Brazil's social assistance system and safety net have

played an important role in maintaining the social

benefits achieved so far by preventing more

Brazilian citizens from falling into poverty. But

budget expansion for the social safety net system is

hampered by a challenging fiscal consolidation

environment in Brazil. Furthermore, minimal labor

costs and long working hours have led Brazil to

collective exploitation and collective poverty.

In 2016 and 2017 there was an increase in

poverty and inequality from the ongoing economic

crisis in Brazil. The deteriorating macroeconomic

conditions and the shrinking labor market in Brazil

have an impact on poverty and inequality. There is

an increase in new poorassociated with the crisis.

The crisis is inseparable from the uncontrolled

circulation of capital in production and

manufacturing by multinational companies.

According to Marx, the production of surplus-value

and the continual need of capitalists to increase

production shows that capitalism only creates its

own grave in the form of a modern proletariat and

that the contradictions of society are intensified in

the system. The Pink Tide movement is a resistance

movement against the global capitalist system, but

the emergence of leftist leaders in Brazil does not

fully reflect socially based policies, but rather shows

the policies of pro foreign companies so that the

form of Pink Tide's populism in Brazil is the market

left, where MNCs originating from the US still

controls production and manufacturing.

The consequence of the adoption of a policy of

the market left is the collective exploitation of the

working class of 174,448, excluding outsourcing,

temporary and seasonal employees from abroad.

Working-class activities that generate more value to

MNCs owners from capitalist countries such as the

US have an impact on the economic crisis of 2016

and 2017. The crisis is also caused by divestment in

2015.

The reduction of several types of assets in the

form of financial or goods. Petrobras, for example,

divested US $ 15.1 billion in 2015-2016 (in 2015

Petrobras divested US $ 0.7 billion) and divested US

$ 19.5 billion in 2017-2018 (Sheng and Junior,

2017).

Apart from the divestment carried out by MNCs,

aspects of productive and active consumers also

played a role in the crisis in Brazil. Where labor

wages are small because part of the fractionof

capital affects purchasing power so that Brazilian

economic growth measured by GDP continues to

decline. The working class which has eight hours of

work only receives fraction wages from the total

value of multinational companies. Even though, the

Lula government, continuing the Cardoso route, has

tried to repair the damage to the production system

in Brazil by focusing on increasing wages and

reducing labor hours. However, a weak left

parliament in Brazil resulted in the rise of

neoliberalism as an alternative solution to the

Brazilian crisis.

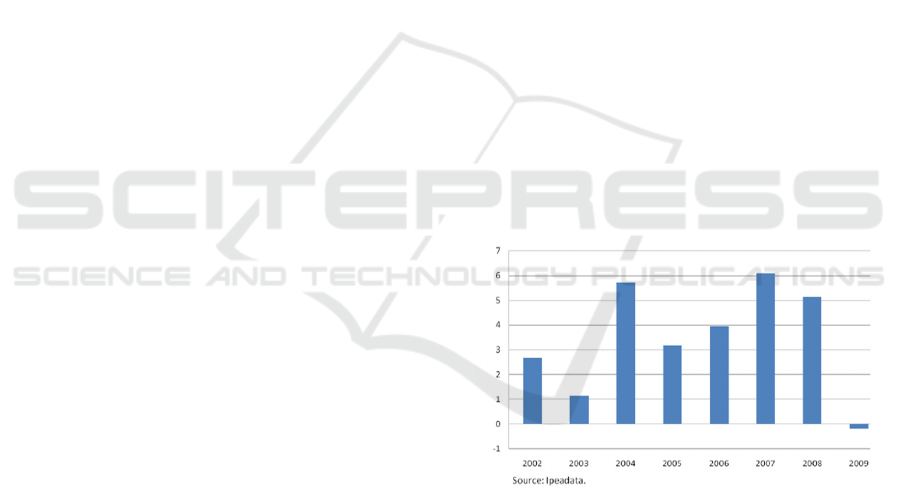

From 2002 to 2009 following the post of

president Lula has restored the average economic

circulation of GDP reached 3.5% compared to 1990

about 2.5%. Nevertheless, the highest annual GDP

in the Lula period was seen in 2007 around 6.1%,

and was seen to be low in 2009 around -0.2% (see

Figure 1) (Fontes & Pero, 2010). This is the impact

of the 2008 global crisis. The global crisis that began

in the US had a significant impact on Brazil's

economic growth in 2009.

Graph 2: Brazil Annual rates of GDP growth.

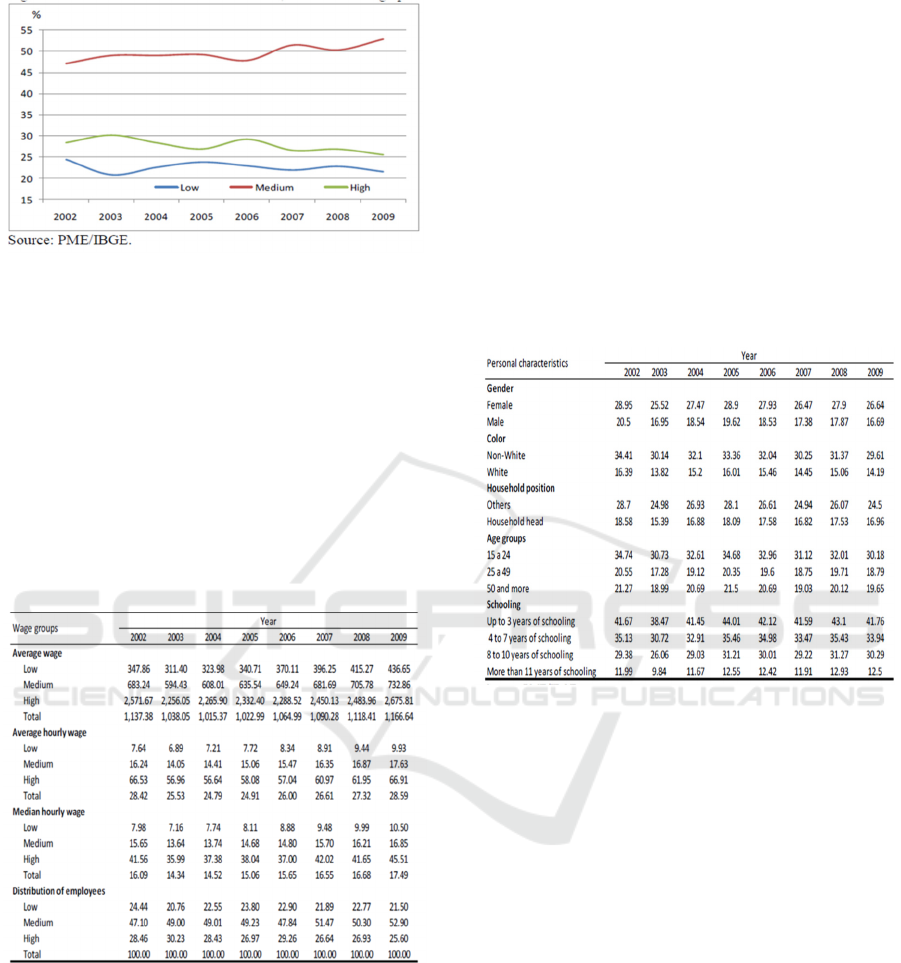

Another important thing to note is the low,

medium and high labor costs. Low wage payments

in Brazil will affect people's purchasing power on

the production of goods and services. Workers

'wages in Brazil are grouped into workers' wages

according to wage groups and based on the character

of the workers. Data in Figure 2 shows 21.5% of

employees in the metropolitan area are considered

low wages, in 2009. The low wages of 24.4% were

seen also in 2002.

ICOSOP 3 2019 - International Conference on Social Political Development (ICOSOP) 3

28

Graph 3: Evolution of the distribution of low, medium and

high paid employees.

As seen in Table 4, there is no significant

decrease. Even though there was no strong decrease

in low-paying jobs, the group's low wages with a

higher average increase and average hourly wages.

For example, the proportion of low-paid employees

decreased by 12.0% from 2002 to 2009, while

medium hourly wages increased by 32.6% (Fontes

and Pero, 2010).

Table 4: Real wages and distribution of employees by

wage groups (Fontes and Pero, 2010).

Table 5 shows that low wages in Brazil can be

measured by employee personal characteristics.

Wage payments in Brazil still look discriminatory

because they are based on gender. Male employees

have higher salaries than female employees. In 2002

there were low wages for female employees of

28.95% and 26.64% in 2009, while male employee

wages were 20.5% in 2002 and 16.69% in 2009.

The percentage of low wages in Brazil was also

seen in personal character based on skin color, in

wherein 2002, non-whiteemployees were paid low

wages of 34.41% and 29.61% in 2009, while white

employees were 16.39% in 2002 and 14.19% in

2009. Low wages were also imposed based on

employee age, where there were 3 groups age given

salary varies. There is a significant percentage in

these three age groups.

Employees aged 15-24 years in 2002 received

low wages of 34.74% and 30.18% in 2009.

Employees in the 25-49 age category received low

wages of 20.55% in 2002 and 18.79% in 2009.

Employees aged over 50 years who received low

salaries of 21.27% in 2002 and 19.65% in 2009.

Table 5: Incidence of low pay by personal characteristics

(Fontes and Pero, 2010).

The data reinforces the argument that although

the Pink Tide movement produced leftist populist

leaders, the collective exploitation of the working

class by MNCs is still visible. So that the Pink Tide

model is characterized by a neo-developmentalism

state in Brazil that is still connected with

neoliberalism. Evidenced by the existence of

political economy activities that are dominated by

non-state actors or individuals. Therefore, in this

finding, Brazil is categorized as the market left. In

which, the expansion of neoliberalism in global

trade is dominated by capitalists even though Brazil

has a left populist leader.

Besides Brazil, Argentina is also categorized as

applying a contemporary left spectrum characterized

by the market left. Where economic growth takes the

form of an industrial cycle that the balance of a

product arises from an imbalance that occurs

continuously in the dialectics of capital. A periodic

over-production crisis is inevitable. The crisis in

Argentina is that the higher the level of productivity

prevails and the higher the socially recognized

average wage, the more difficult it is to increase the

Pink Tide: Neo-developmentalism in Brazil and Argentina

29

level of surplus-value. A critical social and political

crisis will create problems of over-production. Data

shows that foreign expansion in Argentina grew by

26% in 2007 and 33% in 2008 to reach more than

USD 21 billion. Total sales also increased during

this period, although at a slightly slower rate than

foreign sales (see Table 6).

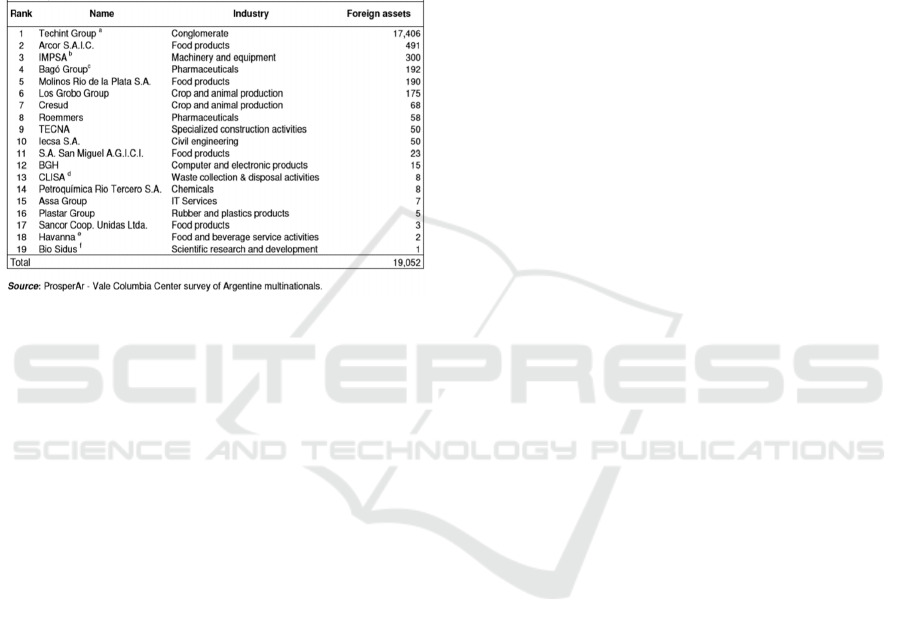

Table 6: Ranking of 19 of the largest Argentine MNEs

investing abroad, 2008 (USD millions) (Nofal, et al.,

2009).

Based on the company data above, the main

motive that drives their internationalization process

is the search for new markets or the preservation of

existing ones. Argentine companies also invest

efficiency in seeking abroad to benefit from

economies of scale and / or risk diversification. In

some cases, the driver for investment is certain

competitive advantages, such as favorable cost

scenarios, highly qualified human resources, or the

ability of companies to meet international quality

standards. The first position in the table above

represents 91 percent of the total foreign assets

controlled by 19 companies held by the Techint

Group. The conglomerate includes two companies

with international status; Tenaris and Ternium. Both

are global leaders in the steel manufacturing sector

with a network of production centers throughout the

world. Arcor, in second place, is one of the leading

global candy exporters and owns most of its

production facilities in Latin America, even though

it has a global presence as the largest hard-candy

producer in the world (Nofal, et al., 2009).

Techint is a group of companies circulating in

more than 100 countries of the world with global

revenues of around USD 26 billion. This figure is

the overall capital accumulation from 4 companies,

namely Tenaris, Ternium, Tecpetrol, and Techint

Ingeniería & Construcción. They accounted for

nearly 80% of the conglomerate's global income.

The four companies are investing in Argentina and

are a component of the Group which has made much

progress in the internationalization process. The

main areas of business for MNCs are steel pipe

manufacturing (Tenaris), flat and long steel products

(Ternium), engineering and construction (Techint

Ingeniería & Construcción), and energy (Tecpetrol).

Ternium has the highest number of foreign affiliates,

53 in 16 countries, followed by Tenaris, 26 foreign

affiliates in 14 countries, Tecpetrol has three foreign

affiliates in three countries and Techint Ingeniería &

Construcción has four foreign affiliates in four

countries. It should also be underlined that Tenaris

and Ternium are the main drivers behind Techint

Group's strong global presence over the past two

decades.

The level of worker exploitation, surplus work

mastery, and surplus value can be increased by

extending the workday and making labor workers

more intensive. Many aspects of work

intensification That involve growth in constant

capital compared to variable capital, namely the fall

in the rate of profit when a worker holds several

production machines.

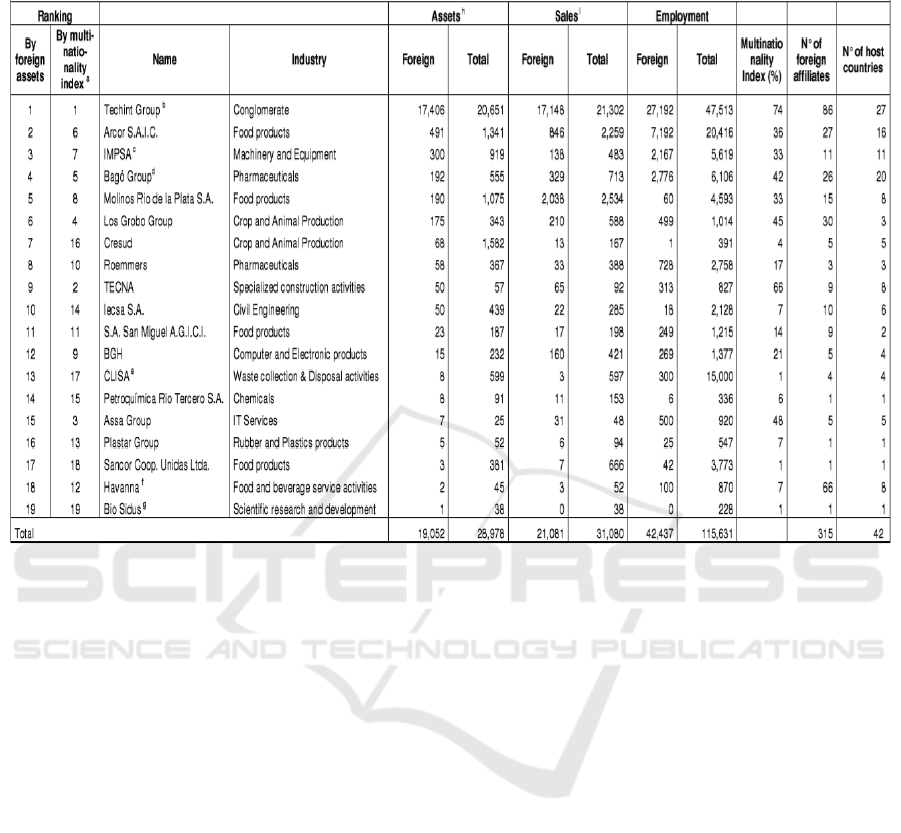

Table 7 shows that there is an investment in

Techint Group's investment assets with a total

investment of USD 20,651 million and employs

47,513 employees. This is a great deal of capital

accumulation. If observed since September 2019, the

national minimum wage (NMW) in Argentina is €

244.6 per month, which is 2,935 euros per year. If

we pay close attention to this wage through the

Argentine peso, the 2019 minimum wage is 15,625

Argentine pesos. Of course, the national minimum

wage has been raised by 1,500 Argentine pesos per

month from the previous year. This increase is less

than the total cost of goods and services purchased

by ordinary consumers or the Consumer Price Index

(CPI) in 2019 so that despite an increase in the

minimum wage, employees continue to lose

purchasing power (Countryeconomy.com, 2019).

ICOSOP 3 2019 - International Conference on Social Political Development (ICOSOP) 3

30

Table 7: Ranking of the 19 Argentine MNEs listed, key variables, 2008 (USD million and number of employees (Nofal, et

al., 2009)

Source: ProsperAr – Vale Columbia Center Survey of Argentina multinacionais.

4 CONCLUSION

Globalization is a paradox. On the one hand, it

creates global economic integration, but on the other

hand, it creates a global crisis. It is closely related to

the market-oriented economic development model or

neoliberalism. The link between economic

globalization and neoliberalism has implications for

social crises due to the economic structure in Latin

America, especially Brazil and Argentina. The

principle of justice, equality, and welfare of

neoliberalism is a nihilism. The enactment of

neoliberalism-based on Washington Consensus

principles in Latin America resulted in a regional

economic crisis which at the same time affected

social inequality. This gave rise to the resistance of

anti-neoliberal society through the Pink Tide

movement.

Pink Tide is a form of dissatisfaction with the

development of neoliberalism. It is a regional Latin

American social movement. Starting from the

response to the failure of the Soviet Union and the

collapse of the Berlin wall, coupled with the failure

of neoliberalism in Latin America. Both factors have

pushed Latin American society into a dilemma.

Where this social movement is not entirely

nuanced left or right. However, it is a mixture of left

and right models. The resulting character also varies.

For example, the Pink Tide in Venezuela and

Bolivia is characterized by a developmentalism

state, while Brazil and Argentina are characterized

by a neodevelopmentalism state.

The implementation of developmentalism state

model does not show any different results from

neoliberalism. The problem raised by this model is

the economic crisis in Brazil and Argentina under

the leftist populist leadership of Pink Tide. This

gives rise to a contradictory understanding of Pink

Tide. A people's movement nuanced equality and

justice inverted the results of these expectations.

Behind this, because Brazil and Argentina still treat

the market as an important actor in development so

that the tendency of exploitation and low wages

colors the circulation of capital. Thus reducing

consumer spending on overproduction in Brazil and

Argentina.

The contemporary left spectrum in Brazil and

Argentina is referred to as the market left, where

Brazil and Argentina through left-populist leaders

implement several policies, namely: First, the

Pink Tide: Neo-developmentalism in Brazil and Argentina

31

market is still dominated by global octopus such as

the IMF, WTO, and WB; Second, international trade

is oriented towards MNCs and; Third, control of

energy resources by the private sector. Of course

there is an anomaly when analyzing the results of the

Pink Tide social movement which recommends

leftist populists to lead the two countries. The leftist

leader who should have taken over all the activities

of production, did not happen, but rather allowed the

market to manage the circulation of capital as a

whole.

The market left gave rise to various conditions in

Brazil and Argentina. The collective exploitation of

the working class of 20 MNCs in Brazil and 19

MNCs in Argentina by applying cheap wages that

are not suitable for working hours. Even MNCs in

Brazil group wages based on personal

characteristics, such as gender, skin color, and age of

employees. Besides, minimum wage increases in

Argentina have no impact on people's purchasing

power on production. Another thing is the over-

production that comes from MNCs assets from

outside Brazilian and Argentinian companies

dominating the capital market, which has an impact

on overproduction.

These various conditions give rise to a

paradoxical argument from the application of the

Pink Tide model. One the one hand, the Pink Tide is

that regional social movements carry the principles

of equality and prosperity. On the other hand, the

neoliberal principle still colors Pink Tide's leftist

populist policies so that it impacts the economic

crisis and social inequality. The neodevelopmentalist

state is called a contradiction or the market left.

REFERENCES

Calvo, G., De La Torre, A., Fernandez, R., Pablo, G.L.,

Paulo, P., Guillermo, Rojas-Suarez, L., 2018. Global

and local challenges in Argentina and Brazil.

Retrieved from https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/

files/global-and-local-challenges-argentina-and-brazil-

english.pdf

Countryeconomy.com, 2019. The national minimum wage

increase in Argentina. Retrieved from https://country

economy.com/national-minimum-wage/argentina,

October 10

th

, 2019.

Elbert, R., 2018. Informality, class structure, and class

identity in contemporary Argentina. Latin American

Perspectives, 45(1), 47–62. Retrieved from

https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X17730560

Fontes, A., Pero, V.P., 2010. Low-paid employment in

Brazil: Área 12 - Economia do trabalho. Retrieved

from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6338503.pdf

Gallas, D., Palumbo, D., 2019. What’s gone wrong with

Brazil’s economy? Retrieved from https://www.bbc.

com/news/business-48386415, October 10, 2019,

Harvey, D., 1989. The condition of postmodernity. In An

enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Retrieved

from https://doi.org/10.2307/2072256

Loureiro, P.M., 2018. Reformism, class conciliation and

the pink tide: Material gains and their limits. In S.I.Y

Stanes M. (Ed.), The social life of economic

inequalities in contemporary Latin America.

approaches to social inequality and difference, 35–

56). Retrieved from /https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-

319-61536-3_2

Marx, K., 2007a. Kapital: sebuah kritik ekonomi politik.

Buku II: Proses sirkulasi kapital (Translated by Oey

Hay Djoen), Hasta Mitra. Jakarta.

Marx, K., 2007b. Kapital: Sebuah kritik ekonomi politik.

Buku III: Proses produksi kapitalis secara menyeluruh

(Translated by Oey Hay Djoen), Hasta Mitra. Jakarta.

Nofal, B., Nahón, C., Donadille, M.E., Pagani, L.,

Fernández, C., 2009. First ranking of Argentine

multinationals finds diversified successes in

internationalization. Retrieved from

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7916/D8DF7037

Pontoh, C.H., 2007. Jalan Amerika Latin. Retrieved fom

https://coenpontoh.wordpress.com/2007/03/19/jalan-

amerika-latin/ on October 10

th

, 2019

Sheng, H.H., Junior, J.M.C., 2017. The top 20 Brazilian

multinationals: Divestment under crises. Retrieved

from http://ccsi.columbia.edu/files/2013/10/EMGP-

Brazil-Report-March-21-2017-FINAL.pdf

Theodore, J.D., 2015. The process of globalization in

Latin America, International Business & Economics

Research Journal (IBER), 14(1), 193–198. Retrieved

from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19030/iber.

v14i1.9044

World Bank, 2019. The world bank in Argentina.

Retrieved from

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/

argentina/overview

ICOSOP 3 2019 - International Conference on Social Political Development (ICOSOP) 3

32