Political Change and Community Development at Traditional Islamic

Boarding School

Akhmad Nurul Kawakip

1

, Imam Rofiki

1

and Abdul Fattah

1

1

Faculty of Education and Teacher Training, Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang, Indonesia

Keywords: Islamic Boarding School, Political Change, Community Development.

Abstract: It was common to see, during new order regime (Soeharto era), that traditional Islamic Boarding School

(pesantren) stayed away from political involvement. In this sense, the Islamic boarding school does not

receive assistance from Indonesian government and strives to be as independent as possible in various ways.

The paper explores how the role of traditional pesantren has been developing during reform era.

Ethnographic approach is employed to explore the conception and practices of Pesantren Sidogiri

concerning political change and community development. Using community development approach, it

argued that Islamic boarding school applied human right approach with its emphasis on equality, dignity,

and justice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Important social and political changes occurred in

the country during the Reformation era. In this

sense, the role of Indonesian pesantren seems to be

significant in the political context, particularly in

East Java. In the 2004 general election, for instance,

the members of DPD (Dewan Perwakilan Daerah or

the upper house of the national parliament) from

East Java dominated by whose backgrounds are

pesantren. Pesantren can be divided into traditional,

modern, and independent. Traditionally the teaching

of traditional pesantren based on classical texts

(Kitab Kuning), which is mainly refer to Syafi’i

school of thought (Tan, 2014).

The result of general election is also proof that

pesantren have been able to respond to social and

political changes. Indonesian pesantren for a long

time had reputation as cultural symbol of Indonesian

social institution which very much based on grass-

roots. When Pesantrens are associated with

Nahdlatul Ulama or NU (the awakening of Muslim

religious scholars), they have the opportunity to

show that their philosophy of education is based on

religious tolerance (Islam Rahmah li al-‘Alamin). In

this sense, NU also promote tolerance Islam, which

is called as Islam Nusantara, it is religious ideology

based on the doctrines of Aswaja (Ahl al-Sunnah wa

al Jama’ah). It is also common to say that Pesantren

is identical with NU and the vice versa. Points out

that the NU is the most loyal and perfect

representation of a Muslim group who declare to the

Sunni doctrine in Southeast Asia. Concerning the

religious ideology, it is wrong to assume that

Pesantren is the breeding ground of radicalism.

Moreover, Islam spread in Indonesia through

pesantrens was “Sufi Islam’’ which was easy to melt

with local culture (Alimi, 2017; Barton, 2017;

Barton and Fealy, 1996; Nathan and Kamali, 2005).

Regarding Indonesia social-political life, it was

common to see the Indonesian government paying

little attention to pesantren development. As

indicated by Bull, “during 1994-1995 government

favoritism was perceived toward Muhammadiyah

and led some pesantren people to feel some distance

from Soeharto regime”. In this sense, the pesantren

community seemed to be marginalized by the

Indonesian government (Lukens-Bull, 2005;

Rahman Alamsyah and Hadiz, 2017).

The paper will focus on how Pesantren Sidogiri

in East Java has responded to the political change.

We examine the pesantrens’ policy toward

Indonesian government legal framework for

pesantren educational system. While the term

“community development” refers to pesantrens’

people participation in social-development over

surrounding society. For these purposes, this paper

answered two primary research questions: how has

the Pesantren Sidogiri responded to political change,

Kawakip, A., Rofiki, I. and Fattah, A.

Political Change and Community Development at Traditional Islamic Boarding School.

DOI: 10.5220/0009916407610766

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Recent Innovations (ICRI 2018), pages 761-766

ISBN: 978-989-758-458-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

761

dan what role have pesantren developed regarding

community development.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Educational system is not a neutral area, because it

is always socially constructed, culturally mediated

and politically intervened. It is like two sides of the

same coin; it can become a site of cultural action for

freedom and at the same time, operate as a means of

cultural action for domestication (Lukens-Bull,

2001; Ouvrard-Servanton et al., 2018). In line with

this perspective, Freire has pointed out: “Neutral

education cannot exist. It is fundamental for us to

know that, when we work on the content of

educational curriculum, when we discuss methods

and processes, when we plan, when we draw up

educational policies, we are engaged in political acts

which imply an ideological choice; whether it is

obscure or clear is not important” (Freire, 1974).

Meanwhile, in the perspective of sociology of

education, the role of government is viewed as

“direct involvement’’. The government has

involvement in education, whether through

ideological beliefs, funding, or setting policy

(Savage and Lingard, 2018).

What is the contribution of pesantren to

community development approach? In this point of

view, it is important to note that one of significant

contributions to the development of educational

system in pesantren is the attention from Indonesian

government through Ministry of religious affair

(MORA), particularly since post-Soeharto era. Since

2005 MORA has already provided scholarships for

pesantren students to pursue degree in various State

Universities in Indonesia. It is argued this

phenomenon add to pesantren educational tradition,

particularly which is called ‘santri kelana’

(wandering santri). According to Dhofier, one of the

important aspects of the pesantren educational

system is the emphasis on the journeying of its

students. A typical wondering santri was a santri

who was travelling from one pesantren to another

pesantren. The aim was to seek knowledge for the

best authorities on the various specialist Islamic

branch of knowledge. Such tradition was the

wandering santri in the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries. It seems appropriate to say that wondering

santri was attributed to santri who traveled from

pesantren to another pesantren (Barton, 2017;

Dhofier, 2014; Schlehe, 2017). Today, in the era of

reformation, the wondering santri is traveling from

pesantren to various universities. We also argue, this

tradition has positive values for the wondering

santri’s future roles as well as to answer the negative

image of pesantren. This is because; it was common

in the past to see that the pesantren curricula were

emphasizing pacification and memorization rather

than a curriculum for empowerment and critical

thinking.

Furthermore, pesantren environment was

isolated from the developments of sciences and

modern society. Those who were in the circle of the

pondok pesantren were not able to solve the

problems which arose due to modern development

(Jainuri, n.d.). The role of doctor, lawyer, engineers,

educators, economist, needed by community, could

not be trained by a traditional Islamic educational

institution, but by a modern one. Thus the pondok

pesantren seemed not to serve the national plans for

modernization adequately. All these assumptions

might be true in the past; however, this assumption

seems not to be true anymore, since many aspects

today have changed in pesantren.

In regards to the community development

approach, Geertz argued that the pesantren

community and kiai could not contribute to

Indonesian development. In this sense, he also

predicted that pesantren community were unable to

deal with the social change that has already

happened in the society (Geertz, 1960). This paper

claims the pesantren community has responded in

dealing with the challenges of social life or

community development issues.

3 METHOD

The main purpose of this article is to explore how

traditional pesantren deal with the political change

and the approach to community development. The

research data obtained from literature review,

document analysis and fieldwork in Sidogiri

pesantren that is located in Pasuruan East Java,

Indonesia. We employed ethnographic method to

explore the conception and practices of Pesantren

Sidogiri concerning political change and community

development. The fieldwork conducted for about 50

days.

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

762

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Legal Framework for the Pesantren

Educational System

Reform era Government policy towards the

pesantren is reflected in Law No. 20/2003 on

National Educational System (Undang-Undang

Sistem Pendidikan Nasional), article 4 (30). The

Law effectively identifies pondok pesantren as a

subsystem of the national educational system. The

Law states: ”religious educational models can be

formed as diniyah, pesantren, pasraman, pabhaja

samanera and the like (Agama, 55).

In 2006, the Minister of Religious Affairs (SK

Mentri Agama) recognized the qualifications granted

by some traditional pesantren (salaf pesantren). This

policy makes them equivalent to those received by

students who graduated from Indonesian state-

owned schools. This policy enables santri to

continue their studies in Indonesian universities. As

a result, the pesantren graduates, particularly at the

senior level, were able to undertake tertiary studies,

not only in state Islamic colleges such as IAIN, UIN

or STAIN, but in other private and state universities

as well (Basyuni, 2008).

The effort to integrate the pesantren into the

national educational system also continued and

accelerated in 2007 with the Government

Regulation. The Government issued Regulation

No.55 of 2007 for the pesantren educational system.

With this Regulation, the pesantren have been

integrated into the Indonesian national educational

system. As a consequence, the Indonesian

government must pay attention to the pesantren’s

educational development, particularly by providing a

small subsidy to some pesantren. One of notable

Indonesian Government subsidies is through BOS

(bantuan operasional sekolah) or the operational

subsidy for schools. The Indonesian government

provided Rp. 235.000 per year per student at the

primary level. While for a student at the senior level,

the Government provided Rp. 324.500 per year.

From this point of view, according to the deputy of

Pesantren Sidogiri, the Pesantren decided to accept

the Indonesian government subsidies:

“Related with BOS bantuan operational sekolah

(operational subsidy for schools) which is provided

by the Indonesian government, Pesantren Sidogiri

does not have the right to refuse the Government’s

financial support. Since the purpose of these funds

is to support the santri, the Pesantren decided to

accept the donation; since the BOS is not allocated

for the Pesantren as an institution”.

The pesantren deputy’s attitude suggests a new

big concern towards external supports, including

from the Indonesian government. This is considered

as a new approach since in the past the Pesantren

Sidogiri refused any financial support from the

Indonesian government. Some of the old

ambivalence remains. The government’s assistance

will be refused when it is given to the pesantren as

an institution but accepted when the recipients are

the

santri (student).

Regarding accreditation, the Indonesian

government also recognised the pesantren’s

qualifications, including some of the traditional

pesantren’s certificates. Ministry of Religious

Affairs data indicates that today there are 32 pondok

pesantren salaf throughout Indonesia who

qualifications have been accepted the government

(report of Subdit V 2007; unpublished). While,

During the Soeharto Regime, the Indonesian

government did not recognize all pesantren salaf

certificates. Their certificates are also considered as

equal to those of Madrasah Aliyah (Islamic senior

high school). With this 2007 government regulation,

the traditional pesantren have become more

integrated into the Indonesian educational system.

For instance, the State Islamic University of Malang

has accepted Pesantren Sidogiri’s certificates.

Another private Indonesian university is also

offering scholarship for Pesantren Sidogiris’ student,

such as STIE Tazkia (Institute for Islamic

Economics) Bogor, UNAS (Bandung National

University), Malang Islamic University (UNISMA)

to pursue degree at various program.

Furthermore, based on the Regulation above, the

Indonesian government through the Ministry of

Religious Affairs has also provided the opportunity

for the traditional pesantren to run a 9-year

compulsory education in the primary level. In

Indonesia, or elementary educational level is called

nine-year compulsory education. It is hoped that

children under 18 years old will be able to pursue at

least nine years of schooling. This policy makes the

pesantren equal to that of the national system run by

public schools, with the requirement to add some

‘secular’ subjects such as mathematics, Bahasa

Indonesia and natural sciences. It is easy for some

pesantren to accept the State policy since the

Regulation does not interfere with the pesantrens’

traditional study of the Kitab Kuning and the

development of the pesantren’s educational values.

The Indonesian government policies have significant

implications for the pesantren as their graduates can

continue their studies in public schools and higher

education institutions. At the same time, the

traditional pesantren have retained their original

Political Change and Community Development at Traditional Islamic Boarding School

763

identity as they have designed their secular

curricula, rather than simply adopted that of the

government.

The government Regulation will also contribute

to the program of compulsory education launched by

the Indonesian government in 1994 in becoming a

reality. In Indonesia, according to the law, children

should attend primary school for nine years, but in

reality poverty was mostly to blame for this not

occurring. In the 1945 Constitution of Indonesia,

article 31, section 1, states: “every citizen shall have

the fundamental right to education.” Traditional

pesantren also share the responsibility to ensure that

compulsory education becomes a reality. In short,

the pesantren become the alternative schools that are

affordable for the village children and adolescents.

With regards to the support of Pesantren

Sidogiri’s development and financial autonomy, the

Pesantren had a reputation for refusing any

donations support or subsidies from outside

organizations, including the Indonesian government

and international development agencies. In 2006, for

instance, an AusAID’ LAPIS program (Learning

assistance projects for Islamic schools) tried to offer

assistance. However, Pesantren Sidogiri refused to

accept this donation. There is a general perception in

Indonesia that an approach like that at Pesantren

Sidogiri is considered conservative. Madjid argues

that the policy of some pesantren trying to distance

themselves from the Indonesian government are

regarded as the manifesting a non-cooperative

attitude. This has been obvious since the colonial era

and remains with some pesantren policies even now

(Majid, 2009). However, for the Pesantren Sidogiri

community, this approach is regarded as no more

than a manifestation of an attempt to keep good

traditions to develop self-reliance not as an

opposition towards the Indonesian government

policy. The deputy of Pesantren Sidogiri explained:

One of the important teaching values in Pesantren

Sidogiri is self-reliance (kemandirian); it is based on

prophet teachings: ‘self-reliance is the foundation to

be successful’. Based on this principle, we work

hard in order not to depend on others, society, and

even the Indonesian government. We have a slogan

‘we should contribute to this country.’ Therefore we

think about what we should give to this country not

what we should get from this country.

This is to say, once again, for Pesantren Sidogiri

that self-reliance is not opposed to the state, but

reflects a determination to be independent.

Regarding financial support and educational

programs, the Pesantren is independent of outside

support. The objectives of social and educational

programs from Pesantren Sidogiri are more directed

to the needs of the surrounding pesantren

community, rather than to the State programs.

Therefore, this article indicates that in the post-

Soeharto era, the Pesantren were increasingly more

open to intervention from Indonesian government.

This is might be because some pesantren leaders felt

more involved in the political process and they also

had parliamentary representatives.

4.2 Pesantren’s Social Role:

Community Development Issues

In addition to religious training, pesantren also play

a social role. Clifford Geertz, when identifying the

role of Javanese pesantren, argued that pesantren

and kiai were only influential in their community

and not among the other two socio-religious

communities: the priyayi and abangan. This

research argues that in social life or community

development issues the contributions of pesantren

did influence not only the pesantren community or

santri but also the broader society. In this sense,

pesantren are also concerned with economic

development and social transformation and they do

not only focus on their role as traditional educational

institutions, but the pesantren also contribute in

reducing poverty (Geertz, 1960).

Pesantren Sidogiri is well known for its

achievements in economic development. Initially,

the growing interest of Pesantren Sidogiri was to

develop social programs based on the pesantren’s

initiative. This is noted in a statement from one of

the leaders of pesantren Sidogiri:

It was initially because of the concern held by

Sidogiri’s teachers about the fact that many people,

particularly surrounding the pesantren, practice riba

(interest) when they get loans from money lenders.

The Pesantren teachers at that time realized that the

Pesantren should be able to address this social

problem. He also refers to Islamic values which is

called as al-ukhuwah Islamiyah (Islamic brother-

hood), and social ibadah (worship). In this context,

he quoted the prophet tradition (al-hadith), “anyone

who does not take care of Muslim Community

affairs is not my followers (ummah).”

To address this social problem, in 1997

Pesantren Sidogiri decided to establish its

microfinance institution, a Shariah finance model

called Baitul Mal wa Tamwil (BMT) or Islamic

micro saving and lending cooperative and

Kopontren (the Pesantren cooperative). Although

BMT institutions are not under Pesantren Sidogiris’

management, BMT managers are consists of elites

and alumni of the Sidogiri Islamic Boarding School.

Initially, the BMT capital was Rp. 13.5 million ($

USD 1800) collected from the pesantren’s teachers.

After seven years in operation, the BMT has 12,470

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

764

customers. Financial transactions reached Rp.35

billion with assets of Rp.8.1 billion. Kopontren

Sidogiri offers financial service programs for people

such as mudharabah or a partnership where the

Pesantren provides the capital. Syirkah wujuh or the

partnership is based on goodwill, credit-worthiness

and a contract, Ijarah or leasing finance (Bakhri,

2004).

The practice of BMT and Kopontren provides

interest-free loans for people to develop small and

micro enterprises. The most important purpose of

giving interest-free loans is to help people escape

from “lintah darat” (moneylenders). Even though

the amount of loans is considered inadequate to

develop a new form of ‘micro-business’, this

program has attracted many people since it generates

opportunities to increase their capital to enhance

their income. In addition, the program raises

productivity. Those who have already run a small

business can increase the volume of “dagangan”

(goods or commodity). While those who are

beginners have the opportunity to develop

alternative income sources other than farming.

Indirectly, the Pesantren deals with

unemployment issues and urbanization problems.

According to the deputy of Pesantren Sidogiri,

Masykuri Abdurrahman, through credit, they create

productive activity in which they can employ many

people. The difficult situation in the agricultural

sector has led many young people to leave their

villages and go to cities or abroad for work. By

giving an opportunity for young people to run

micro-businesses in the village, it is hoped that the

move to the cities can be minimized.

Furthermore, he argues that by distributing and

allocating micro credit to poor people, it empowers

them to be self-reliant and prosper. Many successful

strategies for helping the poor escape from poverty

begin with supporting a family or community’s

assets and then find ways to create alternative

incomes. In this way, the pesantren also contributes

in reducing poverty. The pesantren’s perspective

poverty is fundamental problem that must be solved

as explained by a staff of Pesantren Sidogiri

cooperative.

The task of the Muslim community is not

physical war, but to combat poverty and other social

problems such as malnutrition, providing housing,

clothes and medical assistance for the needy people.

The purpose of this task should not only be for

Muslims, but also for all people who live in the

same community. In this matter, I would like to

make a comparison. Although wine or beer is

forbidden in religious teachings, it still has some

benefits for human beings, while poverty has no

benefits at all for human society. This is our task;

we should put our knowledge into practice.

Year by year, the economic development at

Pesantren Sidogiri has demonstrated significant

progress. The Pesantren has started to produce and

sell drinking water in collaboration with an outside

company (Air Mineral Santri). The revenue from

these business activities provides income to support

the operation of the Pesantren. Besides contributing

to the independence of the pesantren, the Koperasi

Pondok Pesantren (the Pesantren cooperative) also

offers learning experience opportunities for the

students, particularly those who are studying

mua’amalah (economics). These business activities

run by

pesantren are managed by the santri, thus

giving them an opportunity to experience practical

training and business management. In short, the

Sidogiri cooperative opened a new opportunity to

get a job for the community. The case of Pesantren

Sidogiri is also proof that even though the pesantren

makes an effort to maintain the traditional form, the

pesantren is also able to deal with some aspect of

community development. The increasing number of

employee can be seen in Table 1.

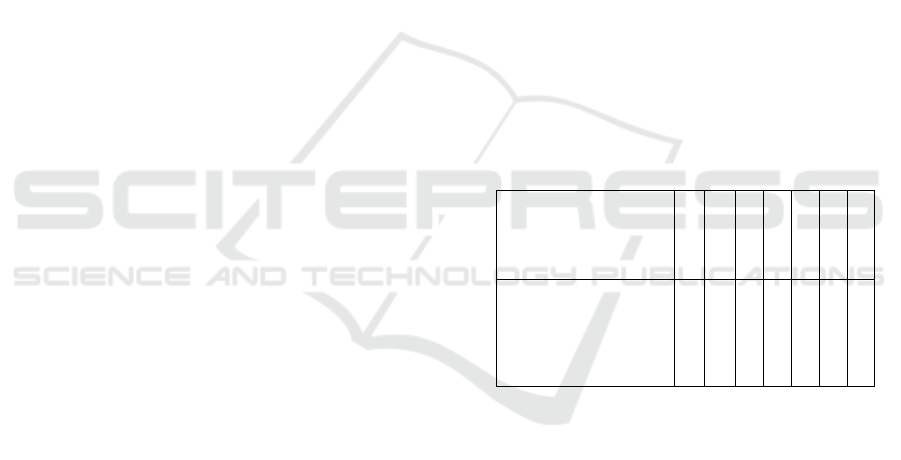

Table 1: The number of employee in Pesantren

Sidogiri Cooperative.

Year

2

0

0

1

2

0

0

2

2

0

0

3

2

0

0

4

2

0

0

5

2

0

0

6

2

0

0

7

The number of employee

4

1

3

4

7

4

6

6

5

7

4

7

7

5

3

9

4

8

1

0

5

0

The creation of pesantren cooperative and BMT

(Islamic micro saving and lending) is advocated by

community development in Pesantren Sidogiri,

benefit both for student, local people and the

pesantren. The pesantren enjoy great advantages

from the community development activities. There is

a range of advantages behind the establishment of

such institution. First, as an educational institution,

Pesantren Sidogiri should be able to provide

considerable sums to finance its own operational

costs, including construction of educational

facilities. Secondly, the establishment of profitable

institutions was also intended to strengthen the

independence of independent pesantren regarding

education funding.

Political Change and Community Development at Traditional Islamic Boarding School

765

5 CONCLUSION

The fall of Indonesian president Soeharto in 1998

opened a political opportunity for civil society

groups, including the traditional pesantren

community, to express their political, social, and

educational ideal more openly. The Indonesian

government also made an effort to develop the

quality of traditional pesantren educational system.

In this sense, the relationship between the pesantren

communities and the State has shown a cooperative

approach. The pesantren also deal with needs of

society. Therefore, we argue that Pesantren Sidogiri

has its own strategies to deal with and respond to

social challenges. In this sense, the effectiveness of

Pesantren Sidogiri to attract people participation in

community development cannot be separated from

pesantrens’ values such as self-sufficiency, social

worship and Islamic brother-hood (al-ukhuwah al-

Islamiyah). In short, being traditional does not mean

the pesantren ignored to economic development and

social transformation.

It is undeniable that in social life or community

development issues, the contribution of pesantren is

important. Pesantren not only focus on the role of an

Islamic educational institution, but it is also

concerned about economic development and social

transformation of the community, such as reducing

unemployment and eliminating poverty. The

creation of BMT or microfinance institution,

Kopontren (the Pesantren cooperative) shows that

the Pesantren indirectly deals with social life and

unemployment issues. In this sense, pesantren

provides interest-free loans for people who would

like to develop ‘small and micro-enterprises’ and

create opportunity to get job. Using the two principal

foundations in community work as identified by Ife

and Tesoriero (Ife and Tesoriero, 2006). The first

principle is a social justice, or human right

perspective refers to equity, dignity, and justice. The

second principle is ecological perspective with its

emphasis on air pollution, global warming, and

water sanitation. It is argued that the community

approach at Pesantren Sidogiri reflect the human

right perspective.

REFERENCES

Agama, K., 55. Tahun 2007 tentang Pendidikan Agama

dan Pendidikan Keagamaan,(2011). Jkt. Dirjen

Pendidik. Islam Kementeri. Agama RI.

Alimi, M.Y., 2017. Rethinking anthropology of Shari’a:

contestation over the meanings and uses of Shari’a in

South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Contemp. Islam 1–29.

Bakhri, S., 2004. Kebangkitan Ekonomi Syariah Di

Pesantren: Belajar Dari Pengalaman Sidogiri. Ed.

Pertama Penerbit Cipta Pustaka Utama Pasuruan.

Barton, G., 2017. Islam and Politics in the New Indonesia,

in: Islam in Asia. Routledge, pp. 1–90.

Barton, G., Fealy, G., 1996. Nahdlatul Ulama. Tradit.

Islam Mod. Indones. Clayton Monash Asia Inst.

Basyuni, M.M., 2008. Muhammad M. Basyuni:

revitalisasi spirit pesantren: gagasan, kiprah, dan

refleksi. Direktorat Pendidikan Diniyah dan Pondok

Pesantren, Direktorat Jenderal Pendidikan Islam,

Departemen Agama, Republik Indonesia.

Dhofier, Z., 2014. The Pesantren Tradition: A Study of the

Role of the Kyai in the Maintenance of the Traditional

Ideology of Islam in Java.

Freire, P., 1974. ‘Education: Domestication or

Liberation?’, in I. Lister (ed.) Deschooling, Cambridge

University. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Geertz, C., 1960. The Javanese Kijaji: the Changing Role

of a Cultural Broker. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 2, 228–

249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500000670

Ife, J., Tesoriero, F.A., 2006. Development. Community

Based Alternatives in an Age of Globalisation.

Jainuri, A., n.d. The reformation of muslim education: A

study of the Aligarh and the Muhamadiyah

educational system. J. IAIN Sunan Ampel XV, 20–28.

Lukens-Bull, R., 2005. A peaceful Jihad: Negotiating

identity and modernity in Muslim Java. Springer.

LukensBull, R.A., 2001. Two sides of the same coin:

Modernity and tradition in Islamic education in

Indonesia. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 32, 350–372.

Majid, N., 2009. Bilik-bilik pesantren: sebuah potret

perjalanan. Paramadina : Dian Rakyat, Jakarta.

Nathan, K.S., Kamali, M.H., 2005. Islam in Southeast

Asia: Political, Social and Strategic Challenges for the

21st Century. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Ouvrard-Servanton, M., Hugo, G.R., Salesses, L., 2018.

Emancipation Education Thanks to a mobile digital

device. Appl. Sci. Innov. Res. 2, 37.

Rahman Alamsyah, A., Hadiz, V.R., 2017. Three Islamist

generations, one Islamic state: the Darul Islam

movement and Indonesian social transformation. Crit.

Asian Stud. 49, 54–72.

Savage, G.C., Lingard, B., 2018. Changing modes of

governance in Australian teacher education policy, in:

Navigating the Common Good in Teacher Education

Policy. Routledge, pp. 74–90.

Schlehe, J., 2017. Contesting Javanese traditions: The

popularisation of rituals between religion and tourism.

Indones. Malay World 45, 3–23.

Tan, C., 2014. Educative Tradition and Islamic School in

Indonesia. J. Arab. Islam. Stud. 14, 47–62.

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

766