Semantic Preference of English Lexicons towards

Bahasa Indonesia-equivalent Words in the Lexical Borrowing

Iwan Fauzi

Department of English Study of Palangka Raya University,

Kampus UPR Jl. Yos Sudarso No. I-A Palangka Raya, Indonesia.

Keywords: English borrowing, semantic preference, Indonesian news context

Abstract: Needless to say that linguistic borrowing is a very common phenomenon and that no language is completely

free of borrowed lexical terms. It is also noticed that languages vary drastically as to the number of foreign

elements comprised therein. This study provides two finding remarks related to English borrowing in

Bahasa Indonesia news contexts; (1) categories of semantic distribution are mostly borrowed in the news

context. In relation to this, it is also to specify whether English loanwords give positive or negative

contribution to a certain semantic field categorized; and (2) linguistic motivation of English loanwords

towards Bahasa Indonesia lexicons which is to attest whether or not they are purely motivated by the lack of

Bahasa Indonesia lexicons. This study used 1,000 English loanwords elicited randomly from the data corpus

built in 2009. There were 3,538 English borrowings in the corpus in which they were downloaded from

three online Indonesian prominent newspapers; Kompas, Koran Tempo, and Media Indonesia. The study

comes to the conclusion that Indonesia news media actually had no reasons to borrow the English

loanwords since they had their counterparts in Bahasa Indonesia lexicons. Of all 1,000 loanwords sampled

in the study showed that the tendency of lexical borrowing in BI is not reasoned by the lack of BI terms to

express the word-filled gap but it is caused by a non-linguistic factor; that is the preference factor of users to

English.

1 INTRODUCTION

At present there are around 6000 languages spoken

in the world and every language has its own distinct

vocabulary containing thousands of words. Speakers

of each of these languages are in contact with others

who speak different languages. It has been found

that when languages come into contact, there is

transfer of linguistic items from one language to

another due to the borrowing of words (Hock, 1986;

B. Kachru, 1989; Y. Kachru, 1982; Thomason and

Kaufman, 1988; Weinreich, 1953). It is a natural

consequence of language contact situations when

expansion in vocabulary such as new words enter a

language (Bloomfield, 1933; Hock, 1976; Aitchison,

1985; and B. Kachru, 1986). Speakers learn words

that are not in their native language, and very

frequently, they tend to be fond of some of the

words in other languages and “borrow” them for

their own use.

The term ‘borrowing’ or ‘loan word’ according

to Mesthrie and Leap (2000) is a technical term for

the incorporation of an item from one language into

another. These items could be (in terms of

decreasing order of frequency) words, grammatical

elements or sounds. Poplack et al. (1988)

specifically indicate that lexical borrowing involves

the incorporation of individual L2 words (or

compounds functioning as single words) into the L1

discourse, the host or recipient language, usually

phonologically and morphologically adapted to

conform with the patterns of that language, and

occupying a sentence slot dictated by its syntax. In

addition, Grosjean (1995) defines that borrowing can

also take place when a ‘word or a short phrase’

(usually phonologically or morphologically) is

borrowed from the other language or when the

‘meaning component’ of a word or an expression in

the foreign language is expressed in the base

language.

1.1 Typology of Borrowing

To name that lexical borrowings is one of linguistic

phenomenon, in many studies sociolinguists prefer to

Fauzi, I.

Semantic Preference of English Lexicons towards Bahasa Indonesia-equivalent Words in the Lexical Borrowing.

DOI: 10.5220/0009019800002297

In Proceedings of the Borneo International Conference on Education and Social Sciences (BICESS 2018), pages 275-283

ISBN: 978-989-758-470-1

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

275

distinguish two types of borrowing, ‘established

borrowings’ and ‘nonce borrowings’. Poplack and

Meechan (1995: 200) defined established borrowings

as lexical items that are morphologically,

syntactically and often phonologically integrated into

the borrowed language. Nonce borrowing is defined

as ‘incorporation’ of a singly uttered word from

another language by a single speaker in some

reasonably representative corpus.

Nonce borrowing, according to Poplack and

Meechan (1998), tend to involve lone lexical items.

These are mostly content words, which display

similar morphological, syntactic and phonological

features as their established counterpart, borrowings.

The only difference is that they are neither recurrent

nor widespread. In this respect, Sankoff et al. (1990)

suggest that the two kinds are best distinguishable

by the degree of syntactic and morphological

integration of the loanword into the host language.

In Bahasa Indonesia or Indonesian (henceforward

mentioned as BI), for instance, the creation of

Indonesian nouns with the addition of the ending –si

is regarded mostly as established borrowings of

Dutch (from -tie) e.g. politie—polisi, informatie—

informasi, etc., and these borrowings have been

established by their incorporation into Kamus Besar

Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian Dictionary) a very

long time ago. Otherwise, some Indonesian

borrowed words differ from their borrowed language

(let’s say English), /c/, /ch/ changing to /k/ e.g.,

claim—klaim, complaint—komplain, corpus—

korpus, champion—kampiun, etc. These loanwords

are regarded as nonce borrowings since they are

neither recurrent nor widespread (Fauzi, 2014). In

this study, the writer prefers to name them as non-

established loans because formally they are still not

recognized as loanwords by the Indonesian

Dictionary.

This is to say that established borrowings are

words integrated into the borrowing language and

non-established borrowings (or nonce borrowings)

are words unintegrated into the borrowing language.

It is important to make clear both terms relating to

this study. The established borrowings are the words

which have been integrated into BI lexicons

becoming a part of the language and no longer

treated as English. Then, non-established borrowings

are words which are still not part of the BI

vocabulary, and these words are also still treated as

English loanwords. More simply, when the

borrowings are found in the Indonesian Dictionary,

these borrowings are regarded as ‘established loans’.

Otherwise, words from the English language which

are not listed in the Indonesian Dictionary are

regarded as ‘non-established loans’. This is a

workable definition to provide a clear demarcation

between established and non-established

borrowings.

1.2 Causes and Motivation of

Borrowing

In most cases, the causes of borrowing is basically

semantic, to express meanings or refer to things or

events which one cannot express in one’s own

language. It can be assumed that the main cause of

borrowing is the need to find lexical items for new

objects, concepts, and places. Langacker (1967: 181)

rightly assumes that it is easier to borrow an existing

word from another language than to make one up.

Some terms, to mention only few, such as internet,

kilowatt, and megahertz are borrowed from English.

On the contrary, some terms such as bamboo, amok,

kampong are few Indonesian words to be borrowed

by English. In this regard, there is no one language

undeniably to borrow words from any other

languages.

According to Kachru (1994) who is one of the

experts in the area of contact linguistics, there are

essentially two hypotheses about the motivations for

the lexical borrowing in languages. One is termed

the “deficit hypotheses” and the other one is the

“dominance hypothesis”. In the words of Kachru

(1994: 139), “the deficit hypothesis presupposes that

borrowing entails linguistic “gaps” in a language and

the prime motivation for borrowing is to remedy the

linguistic “deficit”, especially in the lexical

resources of a language”. This means that many

words are borrowed from other languages because

there are no equivalents in a particular borrowing

language. For example, one will need to borrow

words when s/he needs to refer to objects, people or

creatures which are peculiar in certain places, which

do not exist in his/her own environment and is not

significant in the lives of his/her community, so no

names have been given to refer to those things.

In Higa’s view (1979: 378), “the dominance

hypothesis presupposes that when two cultures come

into contact, the direction of culture learning and

subsequent word-borrowing is not mutual, but from

the dominant to the subordinate”. The borrowing is

not necessarily done to fill lexical gaps. Many words

are borrowed and used even though there are native

equivalents because they seem to have prestige. This

is the case in a prolonged socio-cultural interaction

between the ruling countries and the countries

governed. An example of the dominance hypothesis

is (based on Kachru, 1994) when in the past, the

BICESS 2018 - Borneo International Conference On Education And Social

276

English used to borrow a lot of words from the

languages of their colonizers, particularly from

French. Later, when the English became very

powerful, they colonized many other countries

around the world. The people from these countries

borrowed English words into their languages. At

present, since the English speaking countries have

become advanced, and the English language is one

of the most influential languages of the world,

English lends words to other languages more than it

borrows. This contact between a language and

English is termed “Englishization”.

1.3 Related Studies

Some related studies are concerned with semantic

categories of borrowing in English such as

conducted by Shamimah (2006), Stubbs (1998), and

Garland (1997). Firstly, Shamimah (2006) studies

English loanwords in Malay media. In specific, she

focuses on three aspects: identifying the kinds of

loanwords used in Bahasa Melayu, analyzing the

writers’ purpose of using the English lexical items in

their Bahasa Melayu articles, and finding out the

writers’ attitude and the readers’ response towards

the use of English loanwords with Malay

equivalents. In her findings, Shamimah (2006)

reported that types of English word borrowed into

Malay were mostly dominated by nouns (78.73%).

The two other categories were adjectives (16.60%)

and verbs (4.67%); no adverbs were borrowed. The

characteristics of English loanwords reported from

the findings cover three types of loans namely (a)

words without equivalents, (b) words with close

equivalents (English loans with close but not precise

Malay equivalents), and (c) words with equivalents.

She argued that the writers of newspapers showed a

strong preference for English loanwords against the

Malay equivalents available, for example: ‘trainer’

for jurulatih, ‘review’ for ulasan, ‘instructor’ for

pengajar. She also reported that in some cases the

writers’ preference for the loanwords was absolute

by assuming that it may probably be due to the

journalists reading a lot of news material in English

in their line of work so that they may be strongly

influenced to use such loanwords.

The other main factor that influenced the news

writers’ preference was that many of the English

loans seemed easier to use and understand

(Shamimah, ibid). Dealing with the writers’ attitude

and the readers’ response towards the use of English

loanwords with Malay equivalents, there is a

difference in the preference between the readers and

the writers. What Shamimah could observe from the

pairs of words (English and Malay) that the readers

preferred to maintain using the Malay equivalents as

they are more familiar with them and not yet used to

the English loans while the writers generally

preferred the English loanwords.

Then, Stubbs (1998) analyzes loanwords in

German found through computer-assisted lexical

research. He conducted his study by locating all the

German loanwords since 1900 for which there are

1250, by using the Oxford English Dictionary on

CD-ROM. From the results, one can find that the

influence of German on modern everyday English is

much larger in academic areas. Technical terms are

the largest number of words found, with a total of

750 out of the 1250 loans. The largest sub-categories

of technical terms, 30% in number, are for

mineralogy and chemistry. Many other words come

from biology, geology, botany, medicine, physics

and maths. Many of the technical words were coined

in German from Greek and Latin elements. 80 items

were proper names for people, places, titles of work

of art, etc. Then, 30 words found their way from

earlier forms of German into Yiddish before entering

English. He also found 25 historically motivated

German words from a particular historical period.

These are words borrowed in response to world

political events, such as cold war (1945), sputnik

(1957), Watergate (1972), perestroika (1987),

intifada (1988) (dates show first attested uses in

English and military terms).

Another study is carried out by Garland (1997)

who has located 90 Arabic loanwords since 1950 by

referring to Webster’s third new international

dictionary of the English language (1961), and the

two volumes in the Oxford Addition Series (1993).

Garland made comparisons between the numbers of

Arabic words in different semantic categories. The

leading semantic fields represented are, in the

following order: politics, military, food, Islam,

money and clothing. Politics leads the semantic

ranking. Eleven of the 18 items (21.57%) relate to

colonialism or occupying powers or abettors, for

example, Baath Socialist party in some Arab

countries and in the zila parishad, a district council

in India.

In addition, there are nine food items, with six

starters (tapenade), dips (hummus), soup (

halim),

sandwich (falafel), or salad (tabbouleh), the cooking

device tandoori and the Kwanza feast karamu.

There are eight Islamic terms, three of them naming

Islamic organizations (e.g. Islamic Jehad). The other

five relate to rulings drawn from the Quran or based

on Islamic council decisions, as in the ayatollah’s

fatwa against Salman Rushdie and in various Arab

Semantic Preference of English Lexicons towards Bahasa Indonesia-equivalent Words in the Lexical Borrowing

277

fatwas since then. The Arabs, long famous for

geography, have given English seven recent items

denoting an area or the people associated with it

(e.g. Qatari). Money also offers seven items with

four names of monetary units in Africa (birr) two in

the Middle East (halala) and riel in Cambodia.

Among the five clothing items, hijab is used to refer

to the traditional veil or headscarf worn by Muslim

women. Two other items reflect Muslim dress (e.g.

khansu).

From identifying the semantic categories of

loanwords, one can find out the nature and

significance of borrowing. Stubbs (1998) and

Garland (1997), for instance, argue that English has

borrowed some of the Arab and German political

and military terms to report current issues. However,

Shamimah (2006) indicates that the preference of

using English loans in Malay media is because the

writers have more English influence and exposure as

their job involves international communication and

they are also exposed to a lot of materials in English

when they need to find information.

In relation to this study, the writer would like to

attest (1) to what categories of the semantic

distribution of the loanwords in BI news context are

mostly borrowed; and (2) whether the English

borrowing in BI is motivated by the lack of BI

lexicons or not.

2 METHOD

This study used a corpus of English loans into BI.

The corpus was built by text samples of 1,000

selected loanwords (in random) from written texts in

which the researcher downloaded from three online

Indonesian newspapers (Kompas, Koran Tempo, and

Media Indonesia) during his internship at Radboud

University Nijmegen in 2009. The reason why to

choose these three newspapers is that they are

widespread all over the country. Besides, their

readers range from the ordinary people, students,

businessman, educators, and employees to state

officers. Also, the news contents are provided in a

common language style (the standard Bahasa

Indonesia) that everybody is able to understand.

Before the data selected, the researcher had

7,687 non-BI words with their frequencies selected

by the computer program. After they were verified

by hand, only 3,538 words were eligible to fulfill the

data of this research. From these numbers, the

researcher took 1,000 sentences containing non-

established and established loans equal in number by

pull out them randomly of 3,538 words available.

Borrowing word samples were listed from numbers

0001 to 3538. Then, the writer selected sentences

containing non-established loans first by pulling out

the loanwords which were free from affixes (merely

content words without bound morphemes embedded

to them). The same work was done to select

sentences containing established loans.

Relating to the process of data selection, the

researcher elicited 500 established loanwords first,

then he continued with the rest 500 non-established

loanwords. While selecting the loanwords, once he

found the words with affixes, he went to the next

sample number until it was done by 500 words for

each type of loans. Thus, he elicited and coded those

loanwords in accordance with their semantic

categories in order to find out concentrations of

loanwords based on their semantic fields (this

method is adapted from Poplack et al. 1988). To

complete data processing, he marked the loanwords

whether they have a BI equivalence or not. To do

this work, he referred to two sources of reference:

(1) Glosarium Istilah Bahasa Asing, and (2) a

bilingual dictionary of Kamus Inggris-Indonesia.

The former source is used to check the availability

of specific terms and the latter is used to check the

equivalence of generic terms in BI.

The analysis compared the distribution of

loanwords over semantic fields based on a two-way

classification: loanwords with equivalents and

without equivalents in BI. Then, the analysis also

looked into semantic fields which tended to borrow

English instead of using BI equivalents. The

findings of this section also attested whether the

borrowability in BI was motivated by lexical needs

(when BI had no equivalent words) or it was just

reasoned by another phenomenon (when BI had

equivalent words but the media kept using the

loanwords). The analysis was also calculated

through chi-square test to obtain the p-value for each

semantic field tested.

3 FINDINGS

This study discusses two main findings of lexical

borrowing in Indonesian news context which cover

consecutively semantic fields and the motivation of

borrowed words in the following.

3.1 Semantic Fields in Lexical

Borrowings

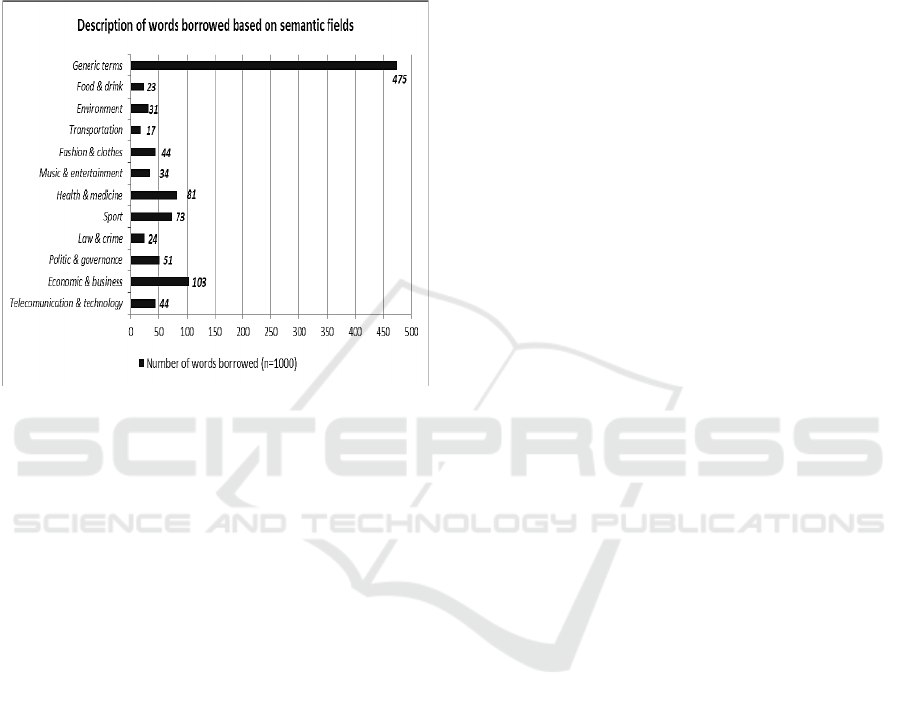

There were twelve rough semantic fields which were

classified based on words borrowed. Those were

BICESS 2018 - Borneo International Conference On Education And Social

278

telecomunication & technology, economic &

business, politic & governance, law & crime, sport,

health & medicine, music & entertainment,

fashion

& clothes, transportation, environment, food &

drink, and generic terms. The following is the

description of words borrowed in accordance with

their semantic fields.

Figure 1: Description of loanwords based on semantic

fields.

Figure 1 shows that generic terms, economic &

business, health & medicine, sport, and politic and

governance are the highest five semantic fields of

borrowing. The generic terms, the loanwords out of

the specified eleven fields as shown on the figure 1,

had the highest number of English borrowing. This

field were notified as generic terms because the

loanwords used might be classified as general

lexicons. There were 475 or 47.5% of loanwords

found in this category which shared 184 words

having no BI equivalents and 291 words having BI

equivalents. From this fact, in generic term the

phenomenon of using English loanwords having BI

equivalent is still popular as well.

The second highest loanwords were occurred in

the economic & business field. There were 103

loanwords of English in this semantic field where 60

words had equivalents in BI and 43 words borrowed

had no equivalents. Those 60 words should not be

borrowed from English because they actually had

their own terms in BI. The economic lexicons of

English such as tax, fund, cost, supermarket, budget,

to mention few, might be able to be replaced with BI

equivalents such as pajak, dana, biaya, pasar

swalayan, and anggaran biaya. However, the news

media prefered to use the English loanwords rather

than BI ones in this field.

The third highest English loanwords were filled

by the terms of health and medicine. This semantic

field had 81 English borrowings where 68 terms

having no equivalents in BI and only 13 terms

having BI equivalents. In this field, BI seems really

lack its own terms to name objects or things. For

instance terms such as caesar, histamin, merozoit,

vena, cardiolipin and so many more are words

which absolutely having no equivalent in BI. Among

13 loanwords having BI equivalents, to mention

some, such as strain, kloning, urine, and imunitas

are actually matched with these terms respectively

galur, peminakan, air kemih, and kekebalan tubuh.

However, those BI equivalents are not commonly

used in BI context rather their English equivalents.

Nevertheless, the English loanwords are more

popular than their BI word pairs.

Sport field is also interesting to be looked into in

relation with the semantic expressibility of lexical

borrowing. The number of loanwords in this field

was the fourth highest of twelve semantic fields

studied. Loanwords having no BI equivalents were

borrowed more highly than those of having BI

equivalents. This might be reasonable because most

sport game are originated from the western

countries. Therefore, many terms in the sport game

are expressed in non-BI words. Of 73 loanwords in

the sport field, 41 terms were found without any BI

equivalents. Let consider these words, to mention

few, such as out-bond, futsal, tie-break, forehand,

wildcard which are reasonably to be borrowed. On

the other hand, 32 words of sport terms may be

possibly named in BI terms such as jumpsuit,

football, hattrick, doping, supporter which are

equivalent respectively to celana kodok, sepak bola,

trigol, pendadahan, and pendukung. However, BI

equivalent terms are less popular than their English

conterparts or even they are rarely used in such sport

context.

The last fifth highest of English loanwords was

filled by the semantic field of politic and

governance. There were 51 words found in the data

which shared 39 terms of loanwords having no BI

equivalents and 12 terms having BI equivalents.

Terms such as campaign, mitigasi, kaukus,

mandataris, hegemoni were actually established

English loanwords without any pair terms in BI. The

equivalent word for campaign is kampanye but this

is not really BI since it adapts the spelling and

pronunciation (established borrowing) of the English

loanwords. Then, the words mitigasi, kaukus,

mandataris, hegemoni are also established loans in

Semantic Preference of English Lexicons towards Bahasa Indonesia-equivalent Words in the Lexical Borrowing

279

BI and they are, in fact, not genuine BI words as

well. Therefore, they were remarked in this study as

loanwords having no BI equivalents.

The other semantic fields such as fashion and

clothes (44), telecommunication and technology

(44), music and entertainment (34), environment

(31), law and crime (24), food and drink (23), and

transportation (17) were loanword fields lower than

50 in the frequency number of borrowings, in which

they ranged from 17 to 44 loan numbers. Of those

fields, only terms in environment which were

significant in number between loanwords having BI

equivalents and having no BI equivalents. In other

words, the number of English borrowing having BI

pairs was higher than those having no BI pairs.

Meanwhile, the other six semantic fields were fairly

balance between both typology of borrowings.

3.2 Motivation to Borrow English

Loanwords

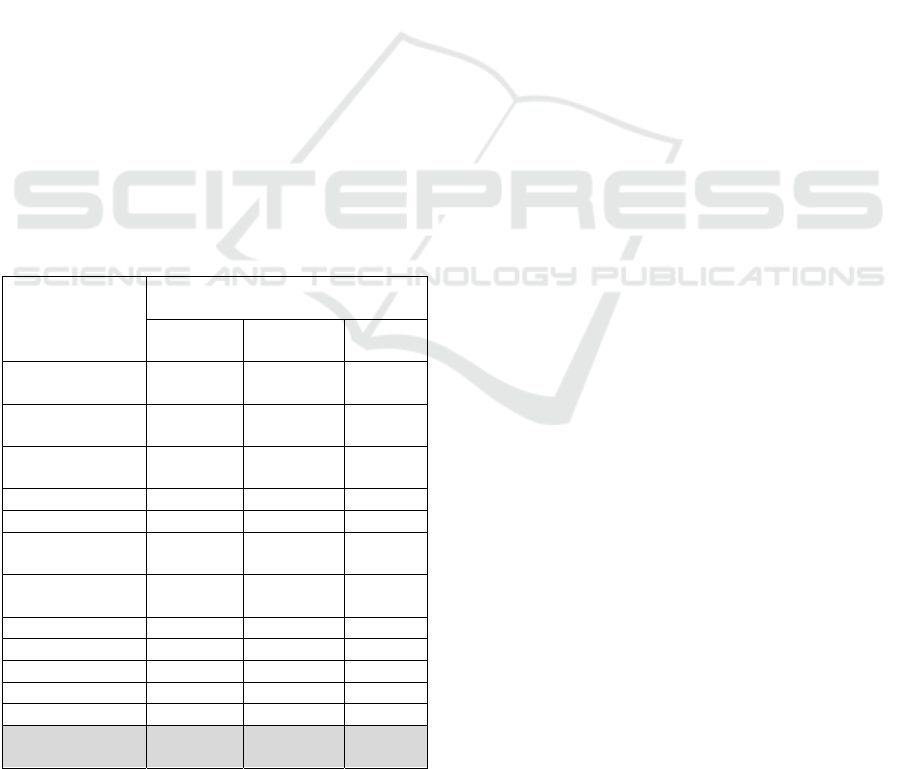

The following table is the description in percentage

and number of loanwords based on semantic fields

by the category of having no equivalent and having

equivalent to BI. The last coloumn on the table is the

p-value indicating the significance level of

borrowing in each semantic field.

Table 1: Description of words borrowed based on

semantic fields, their equivalents, and p-values

Semantic fields

Number of English loanwords and

their percentage

having no

equivalents

having

equivalents

p-values

Telecomunication

& technology

21 (47.7%) 23 (52.3%) .763

Economic &

business

43 (41.7%) 60 (58.3%) .094

Politic &

governance

39 (76.5%) 12 (23.5%) .000**

Law & crime 10 (41.7%) 14 (58.3%) .414

Sport 41 (56.2%) 32 (43.8%) .292

Health &

medicine

68 (84.0%) 13 (16.0%) .000**

Music &

entertainment

16 (47.1%) 18 (52.9%) .732

Fashion & clothes 20 (45.5%) 24 (54.5%) .546

Transportation 7 (41.2%) 10 (58.8%) .467

Environment 21 (67.7%) 10 (32.3%) .048*

Food & drink 15 (65.2%) 8 (34.8%) .144

Generic terms 184 (38.7%) 291 (61.3%) .000**

Overall 485

(48.5%)

515

(51.5%)

.343

** significant at .01

* significant at .05

Table 1 shows that there are five semantic fields

which are positive to borrow English terms in the BI

context since the loanwords which have no BI

equivalent are higher in number than those having

BI equivalent. Those semantic fields are politic and

governance, sport, health and medicine,

environment, and food and drink. However, of those

five fields only three of them are significant in p-

value, i.e., politic and governance, health and

medicine, and environment whereas the other two

fields: sport, and food & drink are not significant in

p-value. It goes without saying that the motivation of

borrowing English words by the three former fields

is positive and significantly motivated by the lack of

BI lexicons while the two fields mentioned later are

also positively motivated by the lack of BI lexicons

but they are not significant in number.

On the other hand, table 1 also shows that

negative motivation of English borrowing toward

BI. It is defined by the seven semantic fields where

the number of loanwords having BI equivalent is

higher than without having BI equivalent, i.e.,

telecommunication & technology, economic &

business, law & crime, music & entertainment,

fashion & clothes, transportation, and generic terms.

Those semantic fields tend to use English terms

instead of saying the terms by using BI lexicons.

However, only one of those fields is significant in

the negative motivation of borrowing; that is generic

terms. The other fields are not significant in p-value

albeit showing result of negative motivation. This is

to say that if the p-value is not significant, the

motivation of using loanwords either positive or

negative is not caused by that BI terms are less

popular than English or the other way round but it is

more likely motivated by non-linguistic factors such

as anyone’s education background or anyone’s

social class.

The data finding also attests that there is an

evidence to say that BI lexicons were less productive

than English loanwords in the fields of such as

telecommunication & technology, economic &

business, law & crime, music & entertainment,

fashion & clothes, and transportation since the

number of loanwords in these fields having BI

equivalent was higher than that of having no BI

equivalent. However, the cause of lexical borrowing

to those six fields aforementioned was not really

negative to BI due to the fact that all their p-values

were not significant. Comparing to the generic

terms, there is a sufficient evidence to say that

English terms were more popular than BI in this

semantic field since the number of loanwords having

BI equivalent was higher than that of having no BI

BICESS 2018 - Borneo International Conference On Education And Social

280

equivalent. The p-value of this field was very

significant.

Of all 1,000 words sampled in the lexical

borrowing showed that the percentage of words

having BI equivalents was higher than that of

without having BI equivalents. However, the

difference of both is not significant in which the p-

value = .343. This means, as a whole, the

phenomenon of lexical borrowing in BI is still

positive which is reasoned to express the word-filled

gap of BI lexicons.

4 DISCUSSION

The researcher considered that the category of

semantic fields were still overlapped but at least the

he named them based on the context that he

rechecked from his data corpus. For instance, he

found the word capital which actually might be in

the generic field but when he looked up the context,

this word collocate with a word modal then he

simply included it in the economic field. In another

example, he found the word survey and when he

looked up in the corpus, he found it in the context of

economic, politic, sport, and even music and

entertainment. For this case, he simply tagged it into

the generic term.

Instead of classifying the semantic field, the most

important thing he also remarked is whether the

lexical borrowing in BI was motivated by the lack of

BI terms in such field or it was just only the

preference of news media using them while BI

actually has already had such terms. In specific,

from those semantic fields he used two references to

decide whether the terms had equivalents or not in

BI by looking them into on the Glosarium Istilah

Bahasa Asing if he regarded them as terms of a

specialized field and also looking them into on the

Bilingual Dictionary of English-Bahasa Indonesia if

he regarded them as only the generic terms.

Furthermore, the researcher had made a clear

constraint between the words which had equivalents

and those which had no equivalent in BI. The

loanwords were regarded having no equivalent in BI

if they corresponded the same form with originated

words by changing orthography only in BI. For

instance, the researcher found the word koktail, jelly,

trik, losion in BI context but they were actually

nonce borrowings of cocktail, gelly, trick, and lotion.

These loanwords are obviously regarded as

“pseudo” BI and they are regarded as loanwords

having no BI equivalent. This is actually the way

Bahasa Indonesia borrows such words (non-

established borrowing) by adapting their

orthographies without the adaptation of

pronunciation (Moeliono et al., 2005). Another

method that the researcher decided to the loanwords

as no BI equivalent was by making them sure to be

listed into the two sources of reference (the glossary

book and the bilingual dictionary) which were used

to confirm their status of BI pairs. More precisely,

the loanwords are purely “alien” when they are

checked either on the glossary book or on the

dictionary that they are listed on one of these

references.

In relation to the result of the study, only three

semantic fields which were positive in English

borrowing. This is to say positive since English

terms are really contributive to those three fields;

politics and government, health and medicine, and

environment. In the politics and government field,

for instance, the loanwords having equivalents in BI

were less than that of having no equivalents. This

means terms of BI lexicons in this field are less or

even absent at all to express such words in BI terms.

Other semantic field which are also not least

important in lexical borrowing is the field of health

and medicine. In this field, BI was really lack terms

to express things or objects except by using English

words. However, this is not to say that BI is poor

with its terms in the health and medicine field. BI,

for instance, has equivalent terms for the English

loanwords such as strain, kloning, urine, and

imunitas which are respectively corresponded to

galur, peminakan, air kemih, and kekebalan tubuh.

Despite this, those four words mentioned later are

not found in medical glossary words instead of their

English equivalents. Nevertheless, the English terms

are more popular than their BI equivalents in this

field. This is to say that English loanwords are

positive to be used in BI context of health and

medicine since BI has no counterparts to them to

express.

It has also the same phenomenon with the

environment field. BI terms could not express or

name things with its lexicon, so that it must be

expressed by loanword terms. Let consider the

words such as tremor, tornado, spesies, evolusi in

which these terms could not be found their

equivalents in BI lexicons. The reason why BI has

no correspondence to such words in its lexicon is

merely reasoned by that those words are culturally

less known in Indonesia before the community

contact. This is in line with Othman (1979) that

states “every community is open to contact with

other communities and culture”. From this notion,

terms loaned aforementioned are not impossibly to

Semantic Preference of English Lexicons towards Bahasa Indonesia-equivalent Words in the Lexical Borrowing

281

be borrowed to fulfill the language need of a certain

field. Hence, the loanword phenomenon in this

regard is positive to the language which borrows.

On the contrary, lexical borrowing also bears

negative contribution to a language which borrows

when the language has its own lexicons or terms to

name the words. The data finding of this study

showed that there are seven semantic fields belong

to this category, i.e.: telecommunication &

technology, economic & business, law & crime,

music & entertainment, fashion & clothes,

transportation, and generic terms. Of those seven

fields, six mentioned former are not significant in

their negative contribution to borrow English but the

last one mentioned—generic terms is very

significant to its negative contribution in English

loanwords. To say negative due to the fact that BI

has equivalents to the words borrowed. Let consider

these words; scanner, website, tax, cost, lawyer,

abuse, supporter, fans, comedian, design, catwalk

and so many in the data corpus which belongs to

negative loanwords in BI context. Those words

indeed have their BI equivalent which are

respectively pemindai, jejaring, pajak, biaya,

pengacara, penyalahgunaan, pendukung,

penggemar, pelawak, rancangan, and pentas

peraga. However, these BI terms are less popular

than English loanwords. Therefore, these semantic

fields have negative contribution to familiarize BI

lexicons.

5 CONCLUSION

In borrowing situation, the borrowing language must

stand to benefit in some way from the transfer of

linguistic material. Bahasa Indonesia inevitably

borrows English especially to express terms which

do not have equivalents. Kachru (1994) is of the

opinion that we cannot deny the fact that English is a

valuable resource in our linguistic repertoire which

must be used to our advantage in spite of the love-

hate relationship with English in Asia and Africa.

To end up this paper the researcher simply

summarizes that the tendency of lexical borrowing

in Bahasa Indonesia is not reasoned by the lack of

the language terms, but it is more reasoned by the

other motivation factor such as prestige or the like.

English words borrowed mostly have had their

equivalents in Bahasa Indonesia but their

equivalents are less prefered and less popular to be

used. To attest this evidence more precisely, there

should be a precise study to look into the motivation

and the behavior of Indonesian speakers who tend to

use English words instead of their own BI lexicons.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank Prof. dr. Rouland van

Hout (Professor of Sociolinguistics of Radboud

University Nijmegen) who had supervised the

researcher’s work during building linguistic data

corpus, and also unforgetably thank to Dr. Hans van

Halteren who assisted the author to computerize the

corpus and gave a space on his office during the

author’s internship. A special thank is also delivered

to Prof. Dr. Agus Haryono, M.Si., the Dean Deputy

of the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education of

Palangka Raya University, who facilitated the author

to present this paper in the conference and also to

publish it on the conference proceeding.

REFERENCES

Aitchinson, J. 1985. Language Change: Progress or

Decay. Cambridge University Press. B. Kachru, 1986

Anonym. 2005. Glosarium Istilah Bahasa Asing. Jakarta:

Pusat Bahasa Departemen Pendidikan Nasional

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1933. Language. New York: Holt,

Rinehart and Winston.

Fauzi, Iwan. 2014. “English Borrowings in Indonesian

Newspapers”. Journal on English as a Foreign

Language. Vol. 4, No. 1: pp. 15-27.

Garland. 1997. 90 post-1949 Arabic loans in written

English. Cairo: Al-Khangi Press.

Grosjean, F. 1995. “A psycholinguistic approach to code-

switching”. In Milroy and Muysken, 259-75.

Higa, M. 1979. Sociolinguistics aspects of word

borrowing. In W Mackey & J. F Ornstein (Eds.)

Sociolinguistic studies in language contact method

and cases. : pp. 277—292 The Hague: Mouton

Publishers,

Hock, Hans H. 1986. Principles of Historical Linguistics.

Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

John M. Echols and Hassan Shadily. 1997. Kamus Bahasa

Inggris-Indonesia. Jakarta: Gramedia.

Kachru, B.B. 1989. The Alchemy of English: The Spread

Functions and Models of Non-native Englishes.

Oxford: Pergamon Press.

_________. 1994. “Englishization and contact linguistics”.

World Englishes. 13, 135-151. University of Hawai’i:

College of Langauges, Linguistics and Literature, and

the East—West Center.

Kachru, Yamuna. 1982. “Corpus planning for

modernization, Sanskritization and Englishization of

Hindi”. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences.

Langacker, R.W. 1967. Language and Its Structure. New

York: Harcourt Brace, Jovanovich, Inc.

BICESS 2018 - Borneo International Conference On Education And Social

282

Mesthrie, R. and Leap, WL. 2000. “Language contact 1:

maintenance, shift and death”. Introducing

Sociolinguistics. Ed. Mesthrie, R., Swann, J., Deumert,

A., and Leap, WL. Edinburgh University Press.

Moeliono, Anton. M., Rifai, Mien. A., Zabadi, Fairul., and

Sugono, Dendy. 2005. Pedoman Umum Pembentukan

Istilah. Jakarta: Pusat Bahasa, Departemen Pendidikan

Nasional.

Poplack, S. and Meechan, M. 1995. “Patterns of language

mixture: nominal structure in Wolof-French and

Fongbe-French bilingual discourse”. In Milroy and

Muysken, 199-233.

_________. 1998. “Introduction: How languages fit

together in code- mixing”. International Journal of

Bilingualism, 2, 127-38.

Poplack, S., Sankoff, D. and Miller, C. 1988. “The social

correlates and linguistic processes of lexical borrowing

and assimilation”. Linguistics, 26: 47-104

Sankoff, D., Poplack, S. and Vanniarajan, S. 1990. “The

case of the nonce loan in Tamil”. Language Variation

and Change, 2: 71-101

Shamimah, Binti Haja Mohideen. 2006. A study of English

loanwords in selected Bahasa Melayu newspaper

articles. Kuala Lumpur: International Islamic

University Malaysia.

Stubbs, Michael. 1998. German loanwords and cultural

stereotypes. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Thomason, Sarah G. and Kaufman, Terrence. 1988.

Language Contact, Creolization and Genetic

Linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Weinreich, U. 1953. Languages in Contact, Findings and

Problems. The Hague: Mouton.

Semantic Preference of English Lexicons towards Bahasa Indonesia-equivalent Words in the Lexical Borrowing

283