The Road User Behaviour of Early-Stage Young Driver in Semarang

Fardzanela Suwarto and Galuh Alfanti

Department of Civil Engineering, Vocational School, Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, Indonesia.

Keywords: Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (Dbq), Young Driver, Risky Driver

Abstract: The Driving style is the manner of the person decides to drive or to their customary driving mode. Where

driver behaviour is a contributory factor in over 90 percent of crashes. One of the major characters that have

been shown to predict risky driving behaviour is age. Young driver are often less concerned with the

probability of the risks caused by traffic situations and more often involved in traffic accident. Young driver

risky behaviour is a major factor that leads to higher accident rates and injuries. Hence the study to understand

young driver is necessary to be able to propose a countermeasure. In this study, an analysis of the

characteristics of young driver will be undertaken to assess driving behaviour and the tendency towards road

safety. The focus of this study is was on the individual profile behaviour that associated with greater

involvement in driving violations, errors and lapses by using Driver Behaviour Questionnaire. The result of

this study confirmed a five factor solution i.e. “Minor Intentional Violations" (25,59%), “Risky Error”

(6,06%), “Lapses” (5,39%), “Dangerous Intentional Violations” (5,01%) and “Straying, and Loss of

Orientation” (4,57%) When the 28 items were ranked according to their rated mean frequencies, the two most

frequently occurring behaviours were: "Sound your horn to indicate your annoyance to another road user" and

"Overtake a slow driver on the inside". On the contrary, the least frequent attitude conducted were "drinking

alcohol when driving"

1 INTRODUCTION

Worldwide traffic accidents have resulted in 1.25

million deaths, as well as 20 - 50 million casualties,

and is the first cause of death for people aged 15-29

years, out performing deadly diseases such as HIV /

AIDS, meningitis, and heart disease (WHO, 2015). In

Semarang the number of traffic accidents tend to

increase every year. The number of accidents

occurred in year 2013 reached 957 events with the

loss value reached Rp 1,438,200,000,-.

The traffic system can be described as the relation

and interaction among road users, roadway and

vehicles. Subsequently, according to Tight (2012), a

road traffic accident came as the result from a

combination of aspects related to a road system

component, the users, the environment, vehicles and

the way they interact. Prior research suggests that

driver behaviour is a contributory factor in over 90

percent of crashes (Petridou and Moustaki, 2001).

The human factor in driving is referring to driving

skills and driving style. Driving style is the manner of

the person decides to drive or to their customary

driving mode, including features such as speed, gap,

and characteristic levels of attentiveness and

assertiveness (Elander et al., 1993).

Basic demographics and behaviors also have long

been cited as major causes of risky driving and traffic

accident (Holland et al., 2010). One of the major

characters that have been shown to predict risky

driving behaviour is age (e.g., Shinar and Compton,

2004). Young risky driver behavior such as speeding

is a major factor that leads to higher accident rates and

injuries (Laapotti et al., 2001; Vassallo et al., 2007).

Further in various countries it has been established

that young novice driver are more often involved in

traffic accident (OECD, 2006; Subramanian, 2006).

Also it has been put forward that young drivers are

often less concerned with the probability of the risks

caused by traffic situations (Deery, 1999). Further in

Central Java, Directorate of Traffic Central Java

Police stated that that most of the traffic accidents that

occurred involved young drivers aged between 16 and

20 years.

In behavioral studies, personality is perceived as

distal predictor of behavior that will be more stable

over time, and tend difficult to alter by behavior-

change interventions (Fishbein and Cappella, 2006).

Suwarto, F. and Alfanti, G.

The Road User Behaviour of Early-stage Young Driver in Semarang.

DOI: 10.5220/0009007901630168

In Proceedings of the 7th Engineering International Conference on Education, Concept and Application on Green Technology (EIC 2018), pages 163-168

ISBN: 978-989-758-411-4

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

163

However, attitudes that characterize affective

evaluation to a certain object, person, or problem, are

more temporary thus can be easier to change with

intervention and subsequently produce long lasting

alterations in behavior (Bohner and Dickel, 2011;

Petty et al., 1997). Hance behaviour change is

expected to reduce the number of traffic accidents and

therefore suitable approaches campaign to promote

traffic safety is significant.

In a study of young drivers Ulleberg and Rundmo

(2003) it showed that the effect of personality traits,

such as altruism, anxiety, normlessness, sensation-

seeking, aggression on risky driving was mediated by

the driver’s attitudes toward traffic safety. In this

study, an analysis of the characteristics of early stages

young driver will be undertaken to assess driving

behaviour and their tendency towards road safety.

The focus of this study was on the individual profile

behaviour that associated with greater involvement in

driving violations, errors and lapses by using Driver

Behaviour Questionnaire. The result of this study will

assist road management agencies in making better-

informed safety-related decisions on regulation and

penalty, as well as designing road safety campaigns.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 The Driver Behaviour

Questionnaire (DBQ)

Driver Behaviour Questionnaire is one the most

widely used measures to assess self reported driving

behaviours (Lajunen et al., 2004). The purpose of the

DBQ findings is that increasing the understanding

between behavioral traits of the driver with the risk of

possible accident will optimize the countermeasure

designed to improve road safety.

The questionnaire contains of 28 items

categorized as bad driving behavior. The association

of each main type of bad driving including violations,

error, and lapses. The difference of both lapses and

error with violation is that violations have an element

of deliberation whereas lapses and errors are

unintentional faults and that they do not reflect what

the driver expected. On the contrary, violations

involve at least one intentional choice of action.

The driver who cross a junction knowing that the

traffic lights have already turned against and

disregard the speed limit on a motorway is behaving

deliberately, while fail to check your rear-view mirror

before pulling out is an inadvertence. The ratting were

then use to assess which types of behaviour the group

of early stages driver are more often involved in.

Because of its distinction then the countermeasure

will also be different. If the behaviour were more

related to. Lapses or error that associated with poor

cognitive resources and information processing, thus

the training designed to increase skill levels is

suggested. On the contrary if the driver behaviour

were more involved to violations such training will

has little effect on the behavioural change, and so it

must be addressed by persuading drivers not behave

in risky driving (Parker et al., 2000).

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 Participant

A total of 272 participants completed the

questionnaire in their class- rooms during school

hours. The sample was drawn from 4 high schools in

the area of Semarang. 272 participants consist of 63%

girls and 37% boys with an age range between 15

until 18 years old. In the research found that the there

were 213 participates classified as early stage driver,

and the rest are intermediate stage driver.

3.2 Driving-Related Measures

The Driver Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ) was used

in this study, with 28 statement items related to

driving behavior, participants being asked to respond

to each item by showing how often they behaved as

shown and answered on five-point Likert scales

ranging from “never” (1) to “always” (5). The items

consists of eight errors and eight lapses, eight

ordinary violations and four aggressive violations

developed by Lawton et al. (1997) and used in several

studies carried out in different countries (e.g., Gras et

al., 2006; Özkan et al., 2006b).

Participants were also asked to estimate their

driver experience by year or month. Moreover, they

were asked to indicate if they have ever received any

violation tickets.

3.3 Attitude towards Road Safety

18 items attitudes scale was included to measure

participants road-safety attitudes related to driving.

All items were answered on five-point response

scales ranging from “never” (1) to “always” (5), with

high scores indicating a positive attitude toward

traffic safety (i.e., wearing helmet when driving).

EIC 2018 - The 7th Engineering International Conference (EIC), Engineering International Conference on Education, Concept and

Application on Green Technology

164

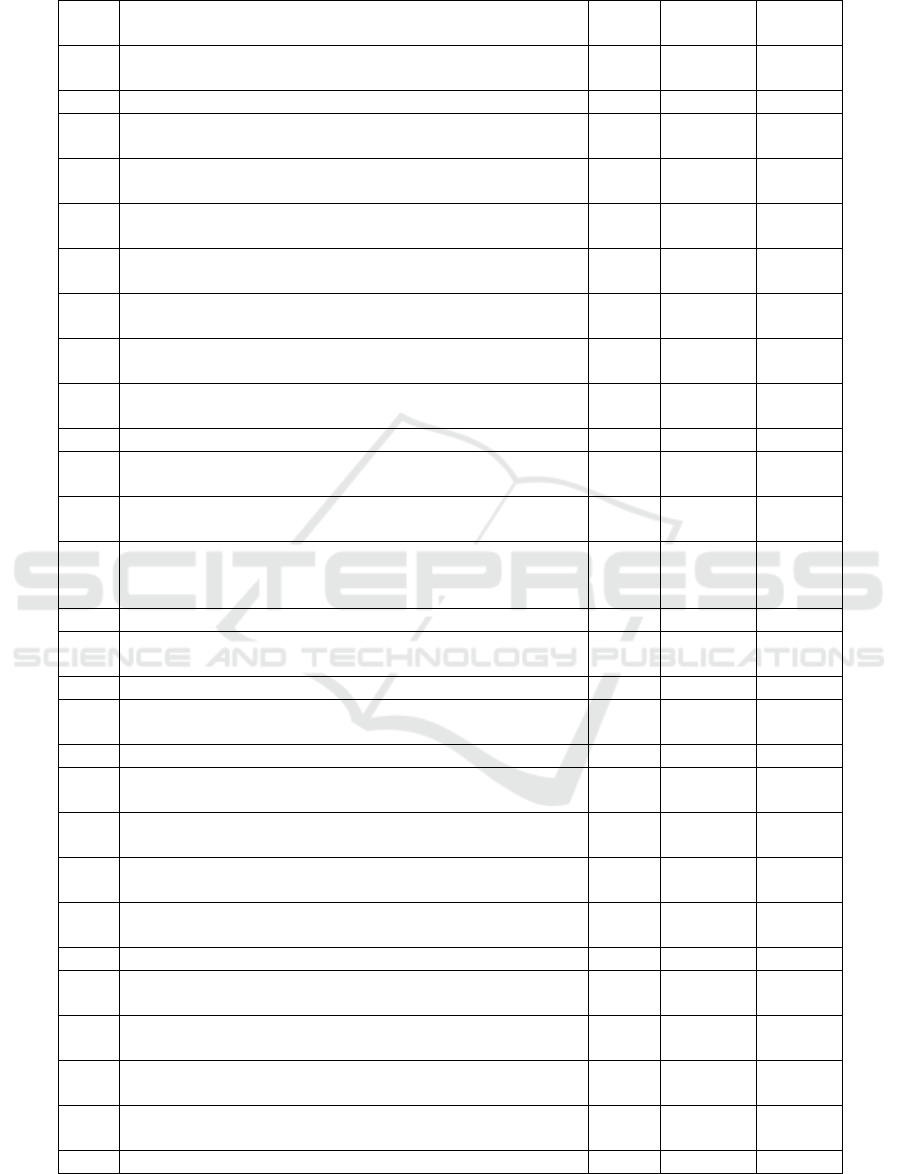

Table 1: Items from the driver behaviour questionnaire (DBQ) in descending order of mean and Standard Deviation score.

Q no Item Mean Std.

Deviation

Variance

26 Sound your horn to indicate your annoyance to another road

user

3.0331 1.15049 1.324

20 Overtake a slow driver on the inside 3.5074 0.9907 0.981

8 Realize that you have no clear recollection of the road along

which you have just been traveling

3.6360 1.0849 1.177

2 Intending to drive to destination A, you “wake up” to find

yourself on the road to destination B

3.9559 0.9556 0.913

16 Underestimate the speed of an oncoming vehicle when

overtaking

3.9669 0.95798 0.918

17 Pull out of a junction so far that the driver with right of way

has to stop and let you out

3.9743 0.96588 0.933

6 Forget where you left your car in a car park Misread the signs

and exit from a roundabout on the wrong road

3.9890 0.99624 0.992

23 Cross a junction knowing that the traffic lights have already

turned against you

3.9926 0.97947 0.959

21 Race away from traffic lights with the intention of beating the

driver next to you

4.0699 1.00492 1.01

24 Disregard the speed limit on a motorway 4.1029 0.95492 0.912

4 Switch one thing, such as the headlights, when you meant to

switch on something else, such as the wipers

4.1213 0.95854 0.919

7 Misread the signs and exit from a roundabout on the wrong

road

4.1287 0.82957 0.688

9 Queuing to turn left onto a main road, you pay such close

attention to the main stream of traffic that you nearly hit the

car in front of you

4.1728 0.83926 0.704

18 Disregard the speed limit on a residential road 4.1765 0.98237 0.965

11 Fail to check your rear-view mirror before pulling out,

changing lanes, etc.

4.1875 0.95167 0.906

5 Attempt to drive away from the traffic lights in third gear 4.1985 1.01879 1.038

12 Brake too quickly on a slippery road or steer the wrong way in

a skid

4.2574 0.80126 0.642

3 Get into the wrong lane approaching a roundabout or a junction 4.2647 0.83939 0.705

22 Drive so close to the car in front that it would be difficult to

stop in an emergency

4.2794 0.79381 0.63

28 Become angered by a certain type of a driver and indicate your

hostility by whatever means you can

4.2831 0.9395 0.883

15 Attempt to overtake someone that you had not noticed to be

signaling a right turn

4.2941 0.89375 0.799

19 Stay in a motorway lane that you know will be closed ahead

until the last minute before forcing your way into the other lane

4.3382 0.89871 0.808

1 Hit something when reversing that you had not previously seen 4.4118 0.81018 0.656

13 On turning left nearly hit a cyclist who has come up on your

inside

4.4191 0.74453 0.554

14 Miss “Give Way” signs and narrowly avoid colliding with

traffic having right of way

4.5147 0.71345 0.509

27 Become angered by another driver and give chase with the

intention of giving him/her a piece of your mind

4.5699 0.82996 0.689

10 Fail to notice that pedestrians are crossing when turning into a

side street from a main road

4.5846 0.71374 0.509

25 I’m drinking while driving 4.9559 0.23893 0.057

The Road User Behaviour of Early-stage Young Driver in Semarang

165

3.4 Statistical Analysis

SPSS 16.0 software, was used to identify the

correlation of driver behaviour and the attitude

towards road safety. Finally, an external validation of

a cluster solution is obtained using significance tests

on relevant criteria variables not used to generate the

cluster solution. In particular, one-way analysis of

variance and chi-square tests were utilized.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

From a total of 272 persons, it was found that 95.955

% were classified as a good driving behaviour

because they are classified as never making errors or

violations on the highway, while 4.045 % classified

as almost never making errors or violations on the

highway. This indicates that, at early stages driver are

rarely intend to violate the traffic rules.

While on a scale attitude towards road safety, it

was found that 73.897 % of students on Semarang

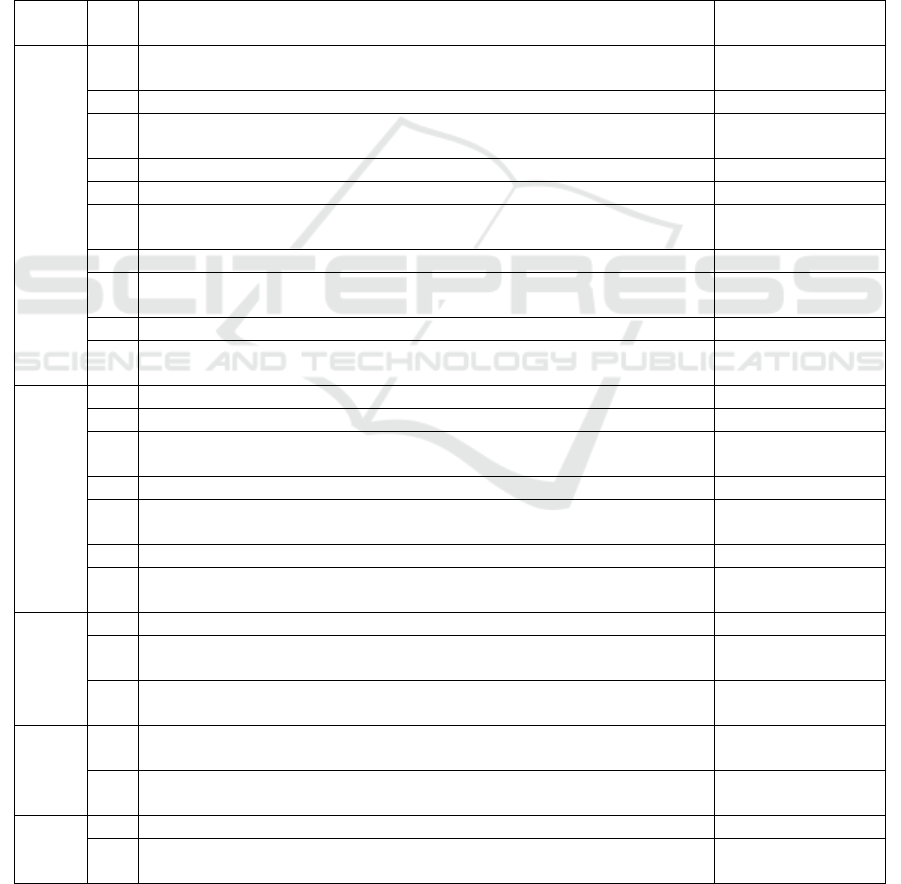

Table 2: Item and Conclusion driver behaviour questionnaire (DBQ).

Factor Q

no

Item

1 023 Cross a junction knowing that the traffic lights have already turned against

you

Ordinary Violation

020 Overtake a slow driver on the inside Ordinary Violation

021 Race away from traffic lights with the intention of beating the driver next to

you

Ordinary Violation

005 Attempt to drive away from the traffic lights in third gear Lapses

024 Disregard the speed limit on a motorway Ordinary Violation

022 Drive so close to the car in front that it would be difficult to stop in an

emergency

Ordinary Violation

016 Underestimate the speed of an oncoming vehicle when overtaking Errors

015 Attempt to overtake someone that you had not noticed to be signaling a right

turn

Errors

007 Misread the signs and exit from a roundabout on the wrong road Lapses

017 Pull out of a junction so far that the driver with right of way has to stop and

let you out

Ordinary Violation

2 013 On turning left nearly hit a cyclist who has come up on your inside Errors

012 Brake too quickly on a slippery road or steer the wrong way in a skid Errors

014 Miss “Give Way” signs and narrowly avoid colliding with traffic having right

of way

Errors

003 Get into the wrong lane approaching a roundabout or a junction Lapses

019 Stay in a motorway lane that you know will be closed ahead until the last

minute before forcing your way into the other lane

Ordinary Violation

018 Disregard the speed limit on a residential road Ordinary Violation

004 Switch one thing, such as the headlights, when you meant to switch on

something else, such as the wipers

Lapses

3 001 Hit something when reversing that you had not previously seen Lapses

009 Queuing to turn left onto a main road, you pay such close attention to the main

stream of traffic that you nearly hit the car in front of you

Errors

002 Intending to drive to destination A, you “wake up” to find yourself on the road

to destination B

Lapses

4 028 Become angered by a certain type of a driver and indicate your hostility by

whatever means you can

Aggressive

Violations

027 Become angered by another driver and give chase with the intention of giving

him/her a piece of your mind

Aggressive

Violations

5 011 Fail to check your rear-view mirror before pulling out, changing lanes, etc. Errors

006 Forget where you left your car in a car park Misread the signs and exit from

a roundabout on the wrong road

Lapses

EIC 2018 - The 7th Engineering International Conference (EIC), Engineering International Conference on Education, Concept and

Application on Green Technology

166

were always obeying road safety rules, 18.015 % of

students are classified as often in obeying road safety

rules. This shows that students in Semarang have a

positive attitude towards road safety.

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations

and rankings (by mean) for all DBQ items. While this

sample of drivers reported each of the error and lapses

items in the DBQ more frequent, they reported

ordinary violations at the same time, with lower

frequencies. For this sample the least frequently

reported item was aggressive violation.

The highest mean was for the item ‘Sound your

horn to indicate your annoyance to another road user”

categorized as Lapses, ‘Overtake a slow driver on the

inside’ that categorized as ordinary violations, and

‘Realize that you have no clear recollection of the

road along which you have just been traveling’ which

considered as error. Meanwhile, the three items with

the lowest mean, were ‘I’m drinking while driving’,

‘Fail to notice that pedestrians are crossing when

turning into a side street from a main road’ and

‘Become angered by another driver and give chase

with the intention of giving him/her a piece of your

mind’ that categorized as Aggressive Violation,

Ordinary violations and Error subsequently.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of

sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity

were used to examine the appropriateness of using

exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The KMO was

0.91 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant

(<0.001), suggesting that the data were appropriate to

factor analyze. Therefore, data from the 1111 students

for the 42 ARBQ items were subject to principal axis

factoring (PAF) with Varimax rotations to explore the

factor structure of the scale (Table 3). The scree plot

suggested three or five potential factors.

The scree plot (Figure 1) specified that the items

behaviour were best fitted by a five-factor solution.

The highest factor accounted for 25.59% total

variance was minor intentional violations. Factor 2

that accounted for 6.06% was Risky Error. Factor 3

accounted for 5.39% was Lapses. Factor 4 Dangerous

Intentional Violations, which accounted for 5.01% of

total variance. And the least factor Straying, and Loss

of Orientation with 4.57% from total variance. The

highest loadings for all factor can be seen in Table 2.

Figure 1: The scree plot for DBQ items.

Taking into account the attitude of early stage

driver toward road safety with their behavior profile,

it can be seen from table 3 that Lapse and Error only

have least correlation with their attitude. Whereas the

relationship is higher for Aggressive Violations. This

state can be occurs because even though the attitude

towards road safety is high, they cannot prevent

unintentional mistakes such as ‘Misread the signs and

exit from a roundabout on the wrong road’ or ‘Fail to

notice that pedestrians are crossing when turning into

a side street from a main road’. Meanwhile for this

attitude rather have an influence on intentional

offenses, for example ‘Become angered by another

driver and give chase with the intention of giving

him/her a piece of your mind’. However, interestingly

the attitude to traffic safety also only has little impact

because this early stage driver with a new driving on

ordinary violations even though it is considered as

intentional action. This might happen experience

only perform positive attitude towards traffic safety

because they were still afraid and choose to be

cautious.

Table 3: Profile Corelation on safety attitude.

Mean SD Minimu

m

Maximu

m

Kolmo

g

orov R Square Resul

t

Lapses

32.7059 4.14874 20 40 1.231

0.010 1.0 %

62.7500 9.45586 26 86 1.399

Errors

34.3971 3.91474 21 40 2.075

0.001 0.1 %

62.7500 9.45586 26 86 1.399

Ordinary Violations

32.4412 4.79047 18 40 1.006

0.006 0.6 %

62.7500 9.45586 26 86 1.399

Aggressive Violations

16.8419 2.09744 10 20 2.304

0.079 7.9 %

62.7500 9.45586 26 86 1.399

The Road User Behaviour of Early-stage Young Driver in Semarang

167

5 CONCLUSION

From the DBQ Profiling, the two items that the early

stages drivers are more frequent done was ‘Sound

your horn to indicate your annoyance to another road

user’ and ‘Overtake a slow driver on the inside’.

Where those two items are categorized as Lapses,

Ordinary Violation. Whereas the two items with the

lowest mean, were ‘I’m drinking while driving’, and

‘Fail to notice that pedestrians are crossing when

turning into a side street from a main road’ that

categorized as Aggressive Violation and Ordinary

violations. The result of this study confirmed a five

factor solution ie “Minor Intentional Violations"

(25.59%), “Risky Error”(6.06%), “Lapses”(5.39),

“Dangerous Intentional Violations”(5.01%) and

“Straying, and Loss of Orientation” (4,57%).

Furthermore, as a whole the driver attitude towards

safety are only has little impact on their profile

behavior since they perform positive attitude towards

traffic safety simply because they were still anxious

and choose to be cautious.

REFERENCES

World Health Organisation, 2015. Global Status Report on

Road Safety 2015. World Health Organization, Geneva.

Tight, M., 2012. Course on Sustainable Transport Policy

(September 2012). Birmingham, United Kingdom:

University of Birmingham.

Elander, J., West, R. & French, D., 1993. “Behavioral

correlates of individual differences in road-traffic crash

risk: an examination of methods and findings”,

Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 113, pp. 279–294.

Holland, C., Geraghty, J. & Shah, K., 2010. “Differential

moderating effect of locus of con- trol on effect of

driving experience in young male and female drivers”,

Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 48, pp.

821–826.

Laapotti, S., Keskinen, E., Hatakka, M. & Katila, A., 2001.

“Novice drivers’ accidents and violations—a failure on

higher or lower hierarchical levels of driving

behaviour”, Accident Analysis & Prevetion, Vol. 33,

pp. 759–769.

Vassallo, S., Smart, D., Sanson, A., Harrison, W., Harris,

A., Cockfield, S. & McIntyre, A., 2007. “Risky driving

among young Australian drivers: trends, precursors and

correlates”, Accident Analysis Prevention, Vol. 39, pp.

444–458.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD), 2006. Young. Drivers: The Road to Safety.

OECD Publishing, Paris, France. Available at

http://www.internationaltransportforum.org/Pub/pdf/0

6YoungDrivers.pdf.

Subramanian, R., 2006. Motor Vehicle Traffic Crashes as a

Leading Cause of Death in the United States, 2003.

Traffic Safety Facts—Research Notes, National

Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Washington,

D.C.

Deery, H. A., Fildes, B. N., 1999. “Young novice driver

subtypes: relationship to high- risk behavior, traffic

accident record, and simulator driving performance”,

Human Factors, Vol. 41, No. 4, pp. 628–643.

Fishbein, M. & Cappella, J. N., 2006. “The role of theory

in developing effective health communications”.

Journal Community, Vol. 56, No. s1, pp. s1–s17.

Bohner, G. & Dickel, N., 2011. “Attitudes and attitude

change”, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 62, pp.

391–417.

Petty, R. E., Wegener, D. T. & Fabrigar, L. R., 1997.

“Attitudes and attitude change”, Annual Review

Psychology, Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 609–647.

Lajunen, T., Parker, D. & Summala, H., 2004. “The

Manchester Driver Behaviour Questionnaire: a cross-

cultural study”, Accident Analysis & Prevention, Vol.

36, No. 2, pp. 231-238.

Parker, D., McDonald, L., Rabbitt, P. & Sutcliffe, P., 2000.

“Elderly drivers and their accidents: the Aging Driver

Questionnaire”, Accident Analysis & Prevention, Vol.

32, pp. 751–759

EIC 2018 - The 7th Engineering International Conference (EIC), Engineering International Conference on Education, Concept and

Application on Green Technology

168