Broadcasting Law Amendment

for Digital TV Migration in Indonesia

Concerning Policy Ideas Fallacy

Titik Puji Rahayu

1

1

Communication Department, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: digital TV, broadcasting, multiplexing, convergence, policy, Indonesia

Abstract: Indonesia has aimed towards digital FTA-TV migration due to the need to increase broadband services for

the society. However, the main obstacle for the migration is the fact that the current Broadcasting Law

No.32 (2002) does not acknowledge ‘multiplex operators’ which are going to be prominent new players in

the digital broadcasting business. In response to this, the Indonesian legislature and executive government

have proposed amendment to the current Broadcasting Law. By applying qualitative policy document

analysis, a literature review and interviews with policymakers, this study examines the amendment drafts

proposed by both the DPR and the Ministry of Kominfo, to identify: how multiplexing and multiplex

operators are proposed to be regulated; what aspects of multiplexing have been overlooked and therefore

left unregulated; how the proposed multiplexing arrangement will potentially impact on competition within

the industry; and finally, these policy documents are seen as reflecting a fallacy in the understanding of

Indonesian policymakers on the technological nature and business of digital broadcasting.

1 INTRODUCTION

Technological convergence increases the demand for

broadband services. Globally, digital broadcasting

migration has been considered to be a solution to

this situation. In Indonesia, the FTA (free-to-air)

television industry has been forced towards digital

migration. The Indonesian Ministry of

Communications and Informatics (henceforth the

Ministry of Kominfo) adheres to the Geneva 2006

frequency plan agreement which sets 17 June 2015

as the deadline for digital broadcasting migration

worldwide.

However, as pointed out by Rahayu (2016), the

main obstacle for implementing digital TV

migration in Indonesia is the current Broadcasting

Law which only acknowledges four types of

broadcasting institutions to hold spectrum licences:

Public Broadcasting Institutions,

Private Broadcasting Institutions,

Community Broadcasting Institutions, and

Subscription Broadcasting Institutions.

The law does not acknowledge ‘multiplex

operators’, which, indeed, are going to be significant

players in the new digital business landscape (p.

234). This is why the legal standing of multiplex

operators was questioned by the Indonesian

legislature, known as Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat

(henceforth the DPR) (Budiman, 2013, p.19).

For this reason, amendment of Broadcasting Law

No.32 (2002) has been considered critically

necessary. The DPR has led the amendment process

since 2010, with the main aim of legalising digital

TV migration and acknowledging multiplex

operators as new players within the Indonesian

broadcasting industry. Unfortunately, up until today,

the policy process shows no sign of approaching an

end.

This article, therefore, aims to investigate

obstacles that have significantly obstructed the

amendment process. As for method, a qualitative

policy document analysis was mainly conducted to

examine both amendment drafts proposed by the

DPR and the Ministry of Kominfo, to uncover: How

are multiplexing and multiplex operators proposed

to be regulated? What aspects of multiplexing have

been overlooked? How will the proposed

multiplexing arrangement potentially impact on

competition within the industry?

Rahayu, T.

Broadcasting Law Amendment for Digital TV Migration in Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0008820002550259

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs (ICoCSPA 2018), pages 255-259

ISBN: 978-989-758-393-3

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

255

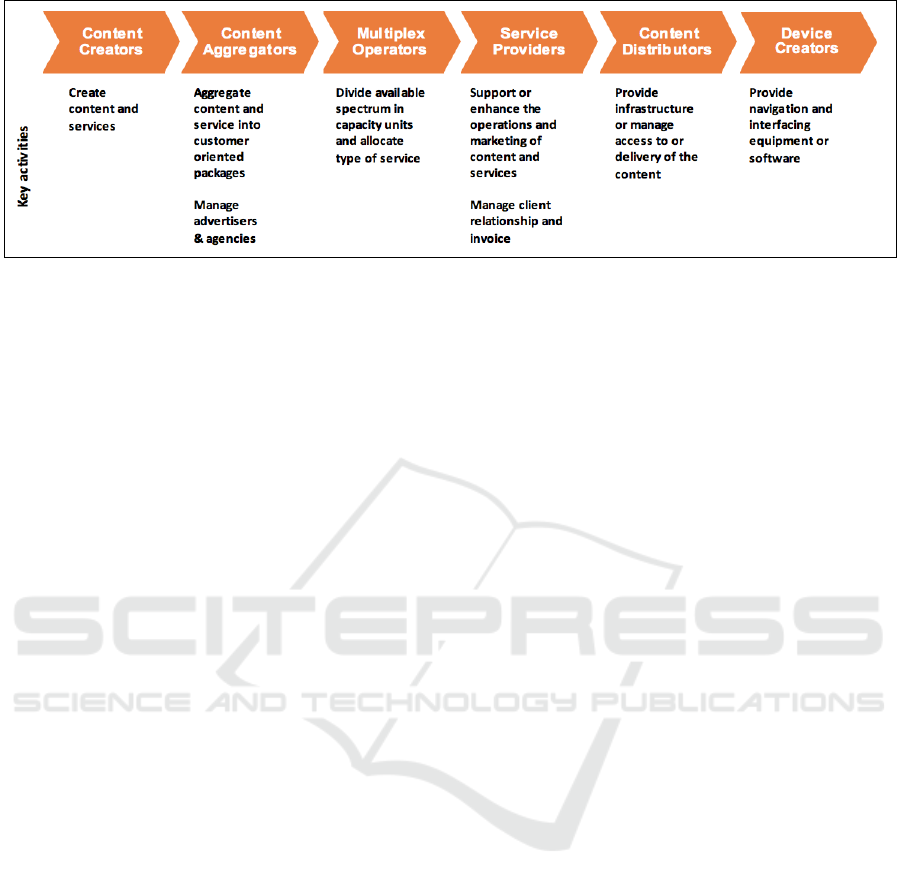

Figure 1: Function/Players in the Digital Value Chain

Source: International Telecommunication Union (2012, p.30)

2 DIGITAL BROADCASTING

DISTINCT ENGINEERING

Digital broadcasting is a phenomenon of both

technological and industrial convergence. Shin

(2006) argues it as “a culmination of

telecommunications and broadcasting convergence”

(p. 42).

Digital broadcasting migration has been

considered as an essential prerequisite for

maximising the benefit of technological

convergence. Papadakis (2007) described how

“convergence gives rise to new services and

applications which are bandwidth intensive,

requiring an existence of broadband infrastructure.

Only with broadband access is the use of complex

services (e.g. multimedia services) attractive or

possible in the first place” (p. 2). Analogue Switch-

Off (ASO), followed by Digital Switchover (DSO)

in the broadcasting sector has been considered to be

a strategic solution to increase the allocation of radio

spectrum for the telecommunication sector in

providing broadband services.

Indeed, digital broadcasting uses multiplexing

technologies which enable more efficient use of

spectrum resources (Song et al., 2015, pp. 4-5). As

explained by Brown (2002, p. 280), “multiplexing

(or multichannelling) is a technical device that

allows the broadcast of multiple programmes

simultaneously on a single transmission. Different

streams of programming are funnelled into a single

data stream for transmission, and at the reception

end the stream is split back into the original multiple

programme streams”. Because of these multiplexing

technologies, one frequency can be used to carry

multiple services, which is known as the “1-to-N

relationship” (International Telecommunication

Union or ITU, 2012, p. 30).

As a result of digital broadcasting migration,

there will be ‘digital dividend’; the part of the

frequency spectrum that is released as a result of the

digitalisation of previously analogue television

services (Börnsen, Braulke, Kruse, & Latzer, 2011,

p. 162). These freed-up spectra can then be

harnessed for broadband services.

At the industrial level, Figure 1 below illustrates

a critical consequence of digital broadcasting

migration in that ‘multiplex operators’ will be

introduced as new players within the broadcasting

value chain (ITU, 2012, p. 30). In this way, the

digitalisation has the potential to alter the ownership

structure in the broadcasting industry.

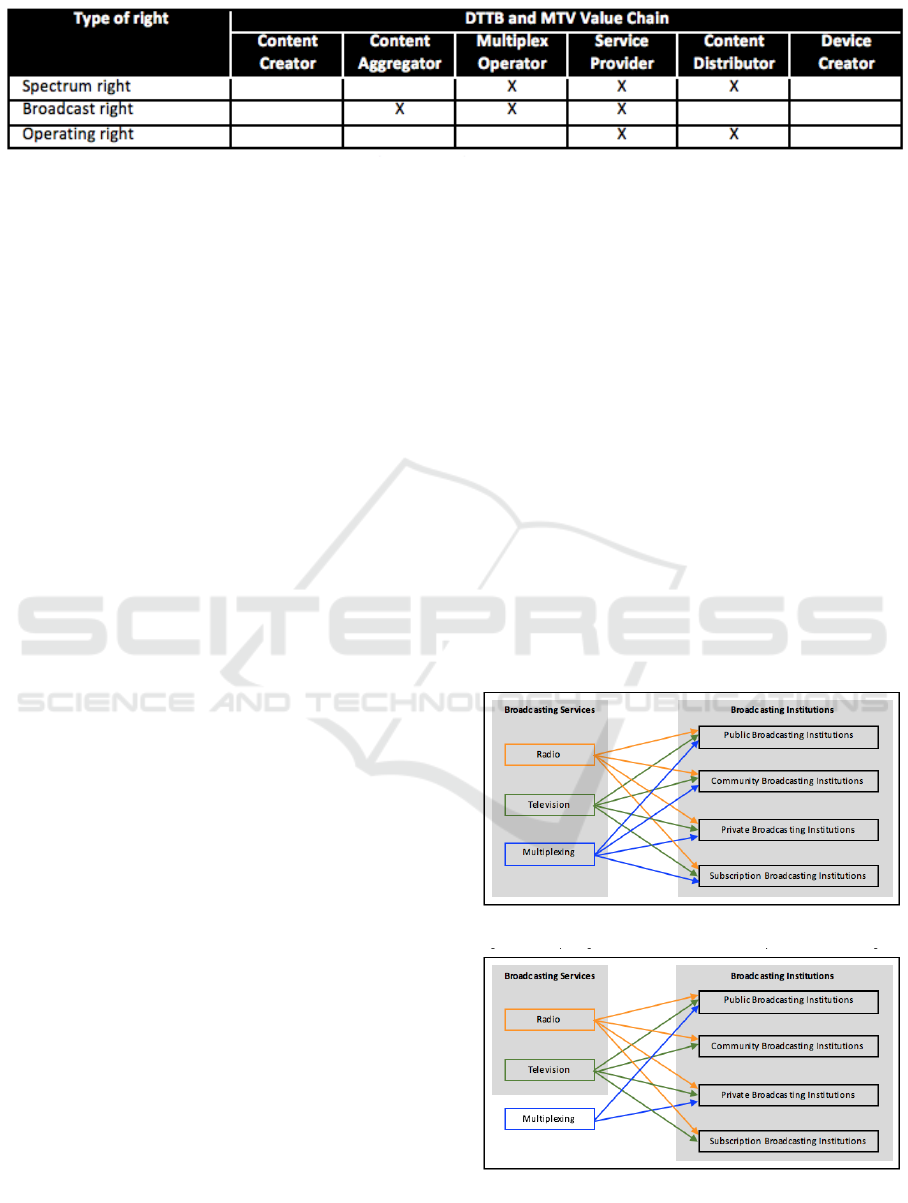

At the regulatory level, digital broadcasting

migration further demands an adjustment in

licensing frameworks (see Figure 2). As explained

by the ITU (2012), in the analogue broadcasting era,

every broadcasting company is simultaneously

granted three rights:

Spectrum rights; “the right to have access and

use a defined part of the radio spectrum in a

designated geographical area for a specified

time period”,

Broadcast rights; “the right or permission to

broadcast television content on a defined

broadcast DTTB/MTV platform in a

designated geographical area and for a

specified time period”, and

Operating rights; “the right to erect and

operate a broadcasting infrastructure in a

defined geographical area for a specified time

period, including aspects such as horizon

pollution, environmental and health hazards”

(pp.28-29).

In the era of digital broadcasting, however, those

three rights need to be granted separately to different

players within the broadcasting value chain, in that

ICoCSPA 2018 - International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs

256

“the broadcaster is not necessarily the frequency

licence holder” anymore. It is now multiplex

operators who are granted the spectrum rights and

who are, therefore, responsible for managing the

defined part of the radio spectrum to carry

programmes or services produced by broadcasters or

content providers. As for digital broadcasters, they

need to obtain broadcast licences for accessing

multiplexing services and broadcast permits for

every programme they aim to broadcast (ITU, 2012,

p. 30).

In this way, digital television migration is a

critical step for both the broadcasting and

telecommunication sectors. Through the

technological transformation, broadband services

can possibly be improved and the diversity of media

ownership can be potentially increased.

However, besides the benefits, digital television

migration tends to be perceived as a threat to

broadcasting incumbents for its potential to alter the

ownership structure within the industry. The main

challenge for regulating digital television migration

is, therefore, to prevent anti-competitive business

conduct by either incumbents or new players,

especially if they are granted the position of

multiplex operators.

3 AMENDING THE LAW WITH

MISUNDERSTANDINGS

ABOUT MULTIPLEXING

As described by the ITU (2012), the digital

broadcasting system introduces ‘multiplex

operators’ as new players within the industry (p. 30).

The term ‘multiplexing’ and ‘multiplex operators’,

unfortunately, do not exist in the current Indonesian

Broadcasting Law No.32 (2002). Thus, the main

progress critically needed to be made in the

amendment of the Indonesian Broadcasting Law for

the legal acknowledgement of ‘multiplexing’ and

‘multiplex operators’.

Analysis of the amendment drafts of

Broadcasting Law proposed by the DPR and the

Ministry of Komminfo reveals different views on

how multiplexing services will be positioned within

the Indonesian broadcasting industry and who will

able to provide multiplexing services. The DPR

categorises multiplexing as a new broadcasting

service, after radio and television, so that all four

broadcasting institutions – The Public Broadcasting

Institution, the Private Broadcasting Institution, the

Community Broadcasting Institution, and the

Subscription Broadcasting Institution –are

considered eligible to become multiplex operators

(see Figure 2). Meanwhile, the Ministry of Kominfo

does not clearly define the position of multiplexing

services, but puts a restriction that only Public and

Private Broadcasting Institutions are eligible to

become multiplex operators (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Possible Licensing Frameworks for Digital Broadcasting

Source: International Telecommunication Union (2012, p.31)

Figure 3: Multiplexing Position in the DPR’s Draft

Figure 4: Multiplexing Position in the Kominfo’s Draft

Broadcasting Law Amendment for Digital TV Migration in Indonesia

257

In my view, multiplexing services should not be

placed on the same level with radio and television

stations. Multiplexing is the technological

infrastructure that facilitates the transmission of

digital radio and television programs, while the

multiplexing service is at the physical/infrastructure

layer, digital radio and television services are at

content layer. While multiplex operators provide

infrastructure services for radio and television

stations, radio and television stations provide content

to their audiences.

None of the drafts clarify the changing players’

roles in the digital broadcasting industry, in which

multiplex operators will act as infrastructure

providers, while digital broadcasters (radio and TV

stations) are going to be only content providers. This

division of player roles is critical as it determines the

type of licensing for those players, as well as their

rights and obligations.

4 AMENDING THE LAW

WITHOUT ADJUSTING THE

LICENSING FRAMEWORK

According to the ITU (2012), in the digital

broadcasting system, it is multiplex operators who

are going to be granted spectrum rights: “the right to

have access and use a defined part of the radio

spectrum in a designated geographical area for a

specified time period” (p. 28). Meanwhile, digital

broadcasters (radio and television stations) are going

to be granted broadcasting rights; “the right or

permission to broadcast television content on a

defined broadcast DTTB/MTV platform in a

designated geographical area and for a specified

time period” (p. 29).

Unfortunately, none of the amendment drafts of

Broadcasting Law specify different licences that are

going to be granted to multiplex operators and

digital broadcasters (radio and television stations).

Both drafts maintain the existence of two licence

forms: Spectrum Licences and Broadcasting

Licences. Both multiplex operators and digital

broadcasters are required to obtain the two forms of

licences.

In my view, policymakers need to make it clear

that Spectrum Licences are to be granted for

multiplex operators, while Broadcasting Licences

are for digital broadcasters (radio and television

stations). The absence of adjustment on the

broadcasting licensing framework reflects a lack of

understanding among policymakers in the DPR and

the Ministry of Kominfo on the distinct engineering

of the digital broadcasting system.

5 AMENDING THE LAW BY

OVERLOOKING

COMPETITION ISSUES

The current Broadcasting Law No.32 (2002) only

makes a general statement on the restriction of

within-industry and cross-industry concentration.

More detail about within-industry and cross-industry

concentration by private TV companies is regulated

through Government Regulation No.50 (2005).

Article 31 of the Government Regulation states that

one legal entity can have only one radio station.

Article 32 states that one legal entity can have a

maximum of two FTA TV stations located in two

different provinces. Meanwhile, article 33 of this

puts restriction on media cross-ownership between

the Private Broadcasting Institution (LPS), the

Subscription Broadcasting Institution (LPB) and a

print media company in the same region.

While the spirit of the current Broadcasting Law

is to prevent ownership concentration, incumbents

get around this ownership policy by establishing a

number of subsidiary companies and using each of

them to apply for two TV Broadcasting Licences

(IPP) in different provinces. In this way,

broadcasting incumbents have managed to establish

many local TV stations throughout Indonesia and

exceed cross-ownership restrictions.

Obviously, the existing ownership policy has

been ineffective in preventing within-industry and

cross-industry expansions by broadcasting

incumbents. Learning from the failure, in their draft

of Broadcasting Law, the Ministry of Kominfo

proposed a stricter rule: if there are two or more

legal entities and/or individuals who become

shareholders in Private Broadcasting Institutions

(LPS) have shareholding relationships, family

relationships (horizontally and vertically up to the

second degree), and/or cooperation to achieve a

common goal (acting in concert), then those two or

more shareholders are considered to be one party

(Buyung Syaharuddin, personal communication,

March 4, 2015).

Regarding media cross-ownership, the draft of

Broadcasting Law by the Ministry of Kominfo only

restricts cross-ownership between the Private

Broadcasting Institution (LPS) and the Subscription

Broadcasting Institution (LPB). Meanwhile, the draft

by the DPR restricts cross-ownership between the

ICoCSPA 2018 - International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs

258

Private Broadcasting Institution (LPS) and print

media companies. So far, the consideration has been

to restrict ownership concentration limitedly in the

content layers, targeted only at content providers.

There has not been any consideration of how cross-

layer ownership needs to be restricted, for example,

to prevent broadcasting institutions from

simultaneously becoming multiplex operators

(infrastructure providers) and digital broadcasters

(content providers).

Cross-layer restriction is critical to prevent anti-

competitive conduct by multiplex operators who are

simultaneously acting as broadcasters. According to

Cave (1997), multiplex operators have the potential

to unfairly treat broadcasters by setting

discriminatory pricing, excessive pricing and even

refusal to supply multiplexing services (p.582).

Unfortunately, as argued by Cave (1997), media

regulators and competition authorities, while they

used to be hostile towards horizontal

monopolisation, tend to be uncertain about how to

respond to vertical integrations (p.581). Due to the

increasing interdependency of the broadcasting and

telecommunication sectors in the era of

convergence, it is critical to maintain the separation

of conduit and content providers, as argued by

Gilder (2000, p.269).

6 CONCLUSIONS

Both the DPR and the Ministry of Kominfo support

digital broadcasting migration and acknowledge the

presence of multiplex operators as new players in

the Indonesian broadcasting industries.

Unfortunately, neither the DPR nor the Ministry of

Kominfo has clearly defined the position of

multiplex operators as physical/infrastructure

providers, different from digital broadcasters that

provide content. It is critical to differentiate

regulatory principles to be imposed on multiplex

operators and broadcasters. Regarding licensing

frameworks, neither the DPR nor the Ministry of

Kominfo have clearly stated that it is multiplex

operators that are going to hold spectrum licences,

not broadcasters.

Regarding ownership restrictions, the amended

version of the Broadcasting Law was aimed at

restricting more within-industry concentration.

Regarding cross-industry ownership, restriction will

only be applied to broadcasting companies who own

print media companies. There is no restriction on

cross-ownership of multiplexing and broadcasting

companies.

REFERENCES

Börnsen, A., Braulke, T., Kruse, J., & Latzer, M. (2011).

The allocation of the digital dividend in Austria.

International Journal of Digital Television, 2(2), 161-

179.

Broadcasting Law No.32 (2002). Jakarta: The Indonesian

Ministry of State Secretariat or Kementerian

Sekretariat Negara (Setneg). Retrieved from

http://www.setneg.go.id/index.php?option=com_perun

dangan&id=302&task=detail&catid=1&Itemid=42&ta

hun=2002

Brown, A. (2002). Different paths: A comparison of the

introduction of digital terrestrial television in Australia

and Finland. International Journal on Media

Management, 4(4), 277-286.

Budiman, A. (2013). Menyoal kebijakan digitalisasi

penyiaran. [Concening broadcasting digitalization

policies]. Info Singkat Pemerintahan Dalam Negeri,

V(20). Retrieved from the People's Representatives

Assembly or Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR)

website:

http://berkas.dpr.go.id/pengkajian/files/info_singkat/In

fo Singkat-V-20-I-P3DI-Oktober-2013-20.pdf

Cave, M. (1997). Regulating digital television in a

convergent world. Telecommunications Policy, 21(7),

575-596.

Gilder, G. (2000). Telecosm: How infinite bandwidth will

revolutionize our world. New York: Free Press.

International Telecommunication Union. (2012).

Guidelines for the transition from analogue to digital

broadcasting: Regional project - Asia-Pacific.

Retrieved from the International Telecommunication

Union (ITU) website: http://www.itu.int/ITU-

D/tech/digital_broadcasting/project-

dbasiapacific/Digital-Migration-Guidelines_EV7.pdf

Papadakis, S. (2007). Technological convergence:

Opportunities and challenges. Retrieved April 5,

2014, from the International Telecommunication

Union (ITU) website:

http://www.itu.int/osg/spu/youngminds/2007/essays/P

apadakisSteliosYM2007.pdf

Rahayu, T. P. (2016). Indonesia’s digital television

migration: Controlling multiplexing, tackling

competition. International Journal of Digital

Television, 7(2), 233-252.

Shin, D. H. (2006). Convergence of telecommunications,

media and information technology, and implications

for regulation. Info: The Journal of Policy, Regulation

and Strategy for Telecommunications, Information

and Media, 8(1), 42-56.

Song, J., Yang, Z., & Wang, J. (2015). Digital Terrestrial

Television Broadcasting: Technology and system.

Canada: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Broadcasting Law Amendment for Digital TV Migration in Indonesia

259