Stigma and Knowledge about Autism Spectrum Disorder among

Parents and Professionals in Indonesia

Muryantinah M. Handayani and Pramesti P. Paramita

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya - Indonesia

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Knowledge, Stigma, Parents, Professionals, Indonesia

Abstract: This study aimed to explore the stigma and knowledge about Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) among

Indonesian parents and professionals (teachers and therapists). Data was collected using The Autism Stigma

and Knowledge Questionnaire (ASK-Q), which was translated into the Indonesian language. The sample

consisted of 125 parents and professionals attending a seminar about autism in Malang, Indonesia. The

results of this study indicated that Indonesian parents and professionals in the sample had adequate

knowledge of autism and did not endorse the stigma of autism. Results are discussed in terms of their

implications for future research and trainings on autism.

1 INTRODUCTION

Three decades ago, Autism Spectrum Disorder

(ASD) was considered to be a rare childhood

disorder (Lord and Bishop 2010). Currently, ASD

has been recognized as “the most common

neurological disorder affecting children and one of

the most common developmental disabilities”

(Leblanc, Richardson, and Burns 2009, 166). The

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention’s Autism

and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network

suggest that in 2012 approximately 1 in 68 children

has been identified with ASD (Christensen et al.

2016). Although there has not been fixed data on the

prevalence of children with ASD in Indonesia, an

increasing rate can be clearly observed. The

government of Indonesia estimated the number of

children with ASD based on the prevalence of

children with ASD in Hongkong, which was 1.68

per 1,000 children on less than 15 years old children.

As the number of children aged 5-19 in Indonesia

reached 66,000,805 in 2010, it was estimated that

there were approximately 112,000 children with

ASD in Indonesia (Jawa Pos National Network,

2013).

ASD represents neurodevelopmental disorder

characterized by difficulties in social

communication, along with restrictive and repetitive

behaviors and interests (Maye, Kiss, and Carter

2017; Matson, et al., 2012). Autism is referred as

spectrum disorder due to the large variability of its

symptoms (Mintz 2017; Reed 2016); some

individuals may display mild symptoms while the

others display more severe symptoms (American

Psychiatric Association 2013). This variability of

ASD manifestation may not only appear between

individuals, but also within themselves from time to

time (National Research Council 2001).

Research has found that there is variability in

ASD knowledge across the general population

(Harrison, et al., 2017). Inaccurate and/or

incomplete knowledge about ASD has been

documented in different countries, such as the

United States, Lebanon, and Japan (Obeid, et al.,

2015; Someki, et al., 2018). In Arab countries,

parents tended to rely on cultural interventions

involving religious healers, or attributed ASD to

vaccines or the ‘‘evil eye’’, which ascribes one’s

misfortunes to ‘‘envy in the eye of the beholder”

(Obeid, et al., 2015). Among students in Japan, there

are misconceptions that autism is not a lifelong

condition and it can be outgrown with appropriate

treatment, that people with autism have low

intelligence and limited empathy, that autism cannot

be diagnosed among toddlers, and that one

intervention works for all people with autism

(Someki, et al., 2018).

Lack of understanding and misconceptions of

autism may lead to bullying and exclusion of

individuals with ASD, as well as stereotyping or

stigmatizing beliefs (Obeid, et al., 2015; Harrison, et

al., 2017). Stereotypes towards those who possess

Handayani, M. and Paramita, P.

Stigma and Knowledge about Autism Spectr um Disorder among Parents and Professionals in Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0008585800970100

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 97-100

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

97

the attributes that do not fit the normative

expectations of society often result in negative

outcomes including, but not limited to, poor self-

esteem and difficulties with employment (Obeid et

al. 2015). Greater knowledge about ASD has also

been associated with lower stigma (Obeid et al.

2015; Harrison et al. 2017; Someki et al. 2018).

In Indonesia, there are cultural beliefs that

problems in pregnancy and/or infancy, breaking the

taboos during pregnancy, karma, God’s plan, and

family size may cause autism (Riany, Y.E.,

Cuskelly, M and Meredith, P., 2016). Riany, Y.E.,

Cuskelly, M and Meredith, P. (2016) highlighted

that in Indonesian culture, children are viewed as a

source of pride for the family and are expected to

bring happiness and wealth. Even though further

investigation is still required, she suggested that

stigma and misconceptions about autism may lead

Indonesian parents to neglect their child with autism.

These parents may fulfil the child’s basic needs

without providing adequate stimulation or being

emotionally available to the child.

The current study aimed to describe the

knowledge and stigma of autism among Indonesian

parents and professionals using a psychometrically

sound assessment tool. Previous research has

explored associative stigma, or stigma attached to

the parent of children with ASD (Kinnear, et al.,

2016), but there has not many research investigating

parents’ stigma toward autism. Theoretically,

researchers have extended the concept of associative

stigma to parent-child relationships within the

context of disability stigma (Kinnear, et al., 2016).

Exploration of parents’ stigma towards autism is

required in Indonesian context due to the indication

that parents may react negatively to their child with

autism. This study also targeted professionals

working with children with autism as they play

important roles in the intervention/therapy which

will affect the efficacy of the result. This study

focused on Indonesian parents and professionals

who already have interest in autism topics, as these

individuals are more likely to have either direct or

indirect interactions with children with autism, and

thus impacting the lives of these children.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

Participants were 126 parents and professionals

attending a seminar about autism in Malang,

Indonesia. The survey was administered before the

seminar began, to avoid any influence on the

participants’ responses. One incomplete response

was not included in the data analysis, so that the data

set consisted of 125 responses. Among the 125

participants, 29 (23.2%) were parents, 68 (54.4%)

were teachers, and 19 (15.2%) were therapists. The

mean age of the participant was 32.49, almost all of

the participants (92.8%) were female, and only 9

participants (7.2%) were male. Most participants

(59.2%) had a bachelor degree, while 26.4%

finished senior high school.

2.2 Material

The survey consisted of a section on participants’

demographic information and the ASK-Q (Harrison

et al. 2017). The ASK-Q has been shown as a

psychometrically sound assessment tool to assess

knowledge and stigma of autism (Harrison et al.

2017). It is comprised of 49 items which are

organized into four subscales: diagnosis, etiology,

treatment, and stigma. Participants were asked to

respond to the statements by selecting “Agree”,

“Disagree” or “Don’t Know.” According to the

scoring protocol, “Don’t Know” answer choice was

coded as incorrect, regardless of the true correct

answer. Some examples of the ASK-Q items are:

some children with autism do not talk, autism is

preventable, there is currently no cure for autism,

autism is a result of a curse put upon/inflicted on the

family. ASK-Q items were selected based on ratings

of face, construct, and cross-cultural validity by a

group of 16 international researchers. Using

Diagnostic Classification Modeling, Harrison, et al.

(2017) confirmed the proposed factor structure and

evaluated the statistical validity of each item among

a lay sample of 617participants.

For the stigma endorsement subscale, a correct

item score is equivalent to not endorsing the stigma.

A scoring template developed by Harrison et al.

(2017) was used to gain participants’ subscale and

total scores. The subscale scores were then

compared to the cutoff scores to identify

adequate/inadequate knowledge and stigma

endorsement/lack of stigma endorsement (Harrison

et al. 2017).

For the purpose of this study, the ASK-Q was

translated into the Indonesian language using a

backward translation approach. The forward

translation was done by the second researcher, while

the backward translation was done by a professional

translator. Both researchers reviewed the final draft

before being used for data collection.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

98

3 RESULT

The result of this study indicated that Indonesian

parents and professionals in the sample had adequate

knowledge of autism. Among the knowledge

subscales, the diagnosis subscale had higher mean

score than the etiology and treatment subscales.

Examination on participants’ individual scores

showed that 93.65% of participants (N=118) had

adequate knowledge on the diagnosis of autism,

while 64.29% of participants (N = 81) had adequate

knowledge on the etiology of autism, and 70.63% of

participants (N=89) had adequate knowledge on

autism treatment. Sixty-two participants (49.6%) had

adequate knowledge in all three subscales.

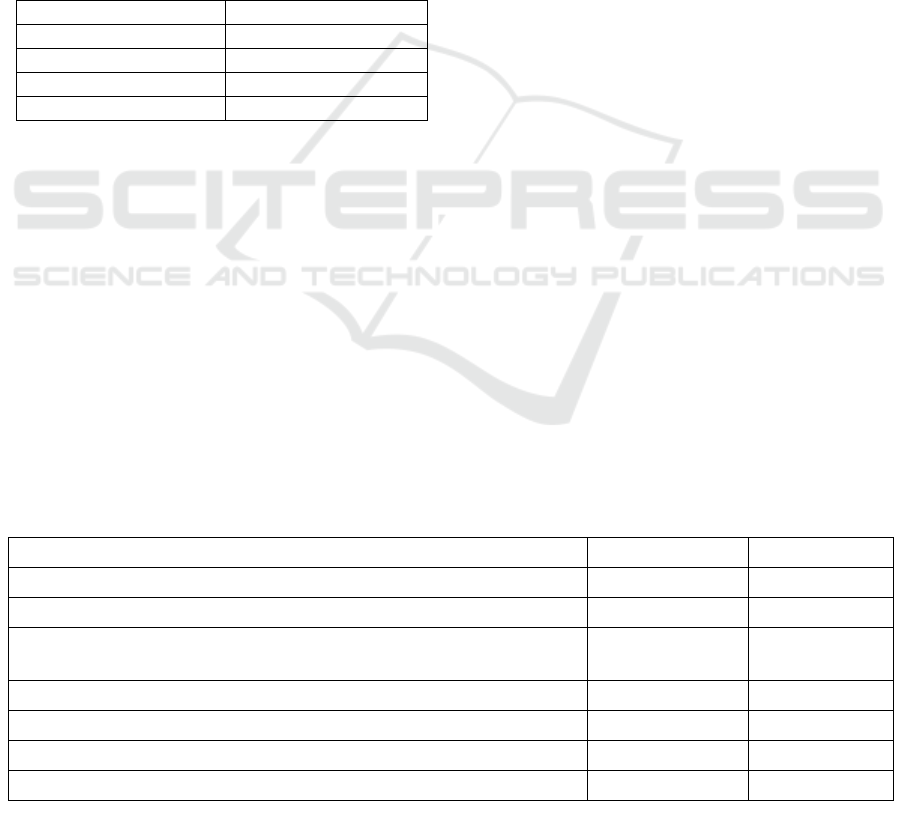

Table 1: Participants’ Mean and Standard Deviation

Scores.

Subscale

Mean (SD)

Diagnosis

13.76 (1.87)

Aetiology

11.27 (1.98)

Treatment

10.52 (1.57)

Stigma

2.93 (1.37)

As described in Table 1, the mean score for

stigma subscale was 2.93, indicating that

participants in this study in general did not endorse

stigma about autism. Eighty participants (63.49%)

did not endorse stigma about autism, but 45

participants (35.71%) endorsed it. A detailed

description of participants’ endorsement for each

autism stigma is described in Table 2. As showed in

Table 2, most participants did not endorse the stigma

related to the preventability of autism and problems

with aggression. However, most participants

endorsed stigma in relation to etiology of autism;

that autism is a result of a curse, cold or rejecting

parents, or traumatic experiences.

4 DISCUSSION

This study aimed to describe the knowledge and

stigma of autism among Indonesian parents and

professionals. Results indicated that Indonesian

parents and professionals in the sample in general

had adequate knowledge of autism and did not

endorse the stigma of autism. Despite the adequacy

of participants’ knowledge on all subscales, higher

mean score was reported for knowledge on the

diagnosis of autism, followed by etiology and

treatment of autism. In regards to autism stigma, the

result of this study indicated that Indonesian parents

and professionals tend to endorse stigma in relation

to etiology of autism; that autism is a result of a

curse, cold or rejecting parents, or traumatic

experiences.

These results suggested that there have been

sufficient training and seminars focusing on the

diagnosis of autism in Indonesia; however more

information on the etiology and treatment of autism

is required. Previous studies have shown that even a

limited amount of training can increase participants’

knowledge about ASD, and lessen autism stigma

(Obeid et al. 2015; Someki et al. 2018). Participants’

endorsement toward the stigma around the etiology

of autism may also be influenced by their cultural

and religious background, although further study is

required to examine this matter.

There are several limitations that should be

considered in interpreting the results of this study.

First, the participants of this study were attending a

seminar about autism. This may indicate their

specific interest in the topic, as well as some

background knowledge about autism. Almost all

participants mentioned that they have heard about

autism, thus their adequate knowledge on all

subscales may not represent those of the general

Table 2: Participants’ Endorsement for Autism Stigma

Stigma

Endorse

Not endorse

Autism is preventable.

39.2%

60.8%

All children with autism usually have problems with aggression.

26.4%

73.6%

Most children with autism are extremely impaired and cannot live

independently as adults.

55.2%

44.8%

Autism is a result of a curse put upon/inflicted on the family.

96.8%

3.2%

Traumatic experiences very early in life can cause autism.

63.2%

36%

Autism is caused by God or a supreme being.

52.8%

47.2%

Autism is due to cold, rejecting parents.

83.2%

16%

Stigma and Knowledge about Autism Spectrum Disorder among Parents and Professionals in Indonesia

99

population in Indonesia. Second, this study only

involved participants from certain areas in

Indonesia. Future study should incorporate larger

samples from various areas in Indonesia to be able to

properly evaluate the psychometric property of the

Indonesian version of the scale.

In short, this study was a first attempt to employ

the ASK-Q in an Indonesian sample. Results

indicated that Indonesian parents and professionals

in the sample in general had adequate knowledge of

autism and did not endorse the stigma of autism,

although many participants endorsed stigma related

to the cause of autism. These findings suggest that

more comprehensive trainings or seminars on autism

should be offered to Indonesian parents and

professionals. These trainings should not only cover

topics around the diagnosis of autism, but also the

etiology and evidence-based treatments of autism.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Autism

Spectrum Disorder Fact Sheet. [pdf] American

Psychiatric Association. Available at:

https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatri

sts/Practice/DSM/APA_DSM-5-Autism-Spectrum-

Disorder.pdf [Accessed 30 June 2018].

Christensen, DL, J Baio, KV Braun, D Bilder, J Charles,

JN Constantino, J Daniels, et al. 2016. "Prevalence

and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and

Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11

Sites, United States, 2012." MMWR Surveillance

Summaries, 2016 Apr 1, Vol.65(3), pp.1-23 65 (3):1-

23. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1.

Christensen DL, Baio J, Braun KV, et al. Prevalence and

Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among

Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental

Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United

States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016; 65(No.

SS-3)(No. SS-3):1–23.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1

Harrison, A. J., Bradshaw, L. P. N. C., Naqvi, M. L. Paff,

and Campbell, J. M.. 2017. Development and

psychometric evaluation of the autism stigma and

knowledge questionnaire (ASK-Q). Journal of Autism

Developmental Disorder 47 (10), pp. 3281-3295.

Jawa Pos National Network, 2013. Penderita autisme di

Indonesia terus meningkat: tak banyak tenaga medis

yang tertarik. Jawa Pos National Network [online] 21

December. Available at:

<https://www.jpnn.com/news/penderita-autisme-di-

indonesia-terus-meningkat> [Accessed on 30 June

2018]

Kinnear, S.H., Link, B.G., Ballan, M.S., and Fischbach,

R.L., 2016. Understanding the experience of stigma

for parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

and the role stigma plays in families' lives. Journal

Autism Developmental Disorder 46, pp. 942-953

Leblanc, L., Warnie, R., and Kimberly, A. B., 2009.

Autism spectrum disorder and the inclusive classroom:

Effective training to enhance knowledge of ASD and

evidence-based practices. Teacher Education and

Special Education 32 (2), pp 166-79.

Lord, C. and Somer, L.B., 2010. Autism Spectrum

Disorders: diagnosis, prevalence, and services for

children and families. Sharing Child and Youth

Development Knowledge, 24 (2), pp. 3-21. Available

at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED509747.pdf.

[Accessed 30 June 2018].

Matson, J.L., Nicole, C. T., Jennifer, B., Robert, R.,

Kimberly, T., and Michael, L. M., 2012. Applied

behavior analysis in Autism Spectrum Disorders:

recent developments, strengths, and pitfalls. Research

in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6 (1), pp.144-150

Maye, M.P., Ivy, G.K. and Alice, S.C., 2017. Definitions

and classification of autism spectrum disorders..In

David, F.C., Dianne, Z and Angi, S.M., eds. 2017.

Autism spectrum disorders: Identification, education,

and treatment. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Mintz, M., 2017. Evolution in the understanding of

Autism Spectrum Disorder: historical perspective.

Indian Journal Pediatrician, 84 (1), pp. 44-52.

National Research Council, 2001. Educating children with

autism. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Obeid, R., Daou, N., DeNigris, D., Shane-Simpson, C.,

Brooks, P.J., and Gillespie-Lynch, K., 2015. A cross-

cultural comparison of knowledge and stigma

associated with autism spectrum disorder among

college students in Lebanon and the United States.

Journal Autism Developmental Disorder, 45 (11), pp.

3520-3536.

Reed, P., 2016. Interventions for autism: evidence for

educational and clinical practice. West Sussex: John

Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Riany, Y.E., Cuskelly, M and Meredith, P., 2016. Cultural

belief about autism in Indonesia. International Journal

of Disability, Development and Education, 63 (6), pp.

623-640.

Someki, F., Torii, M., Brooks, P.J., Koeda, T., and

Gillespie-Lynch, K., 2018. Stigma associated with

autism among college students in Japan and the United

States: an online training study. Research in

Developmental Disabilities, 76, pp. 88-98.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

100