Correlation of Interpersonal Factors, Situational with Cervical

Cancer Prevention in Woman of Childbearing Age

Ni Ketut Alit Armini, Rista Fauziningtyas and Anneke Widi Prastiwi

Faculty of Nursing Universitas Airlangga, Kampus C Mulyorejo, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: Cervical Cancer, Woman, Childbearing, Prevention.

Abstract: Cancer is the main cause of death and disability in the world, especially in women. Regarding cervical

cancer, women can be pressed to participate in primary and secondary prevention. Cervical cancer

prevention in Indonesia is not a priority for women of childbearing age. This research used a cross-sectional

approach. Simple random sampling was and 159 woman of childbearing age were selected as respondents.

Independent variables involved interpersonal and situational factors. The dependent variable was the

prevention of cervical cancer. Data were collected by questionnaires and analyzed using Spearman's Rho

test with a significant level of α ≤ 0,05. This showed the relationship between interpersonal factors with

cervical cancer prevention at p = 0.000 and situational factors relating to cervical cancer prevention at p =

0.000. Interpersonal factors and situational factors have a significant relationship with the primary and

secondary prevention of cervical cancer. These results can be referenced in future research related to other

factors of HPM theory such as previous experience, urgency, perceived benefits of actions, the perceived

barriers of actions, activity related to effects, and commitment in prevention. Health officers should try to

improve information about cervical cancer prevention methods in a form that people can easily understand.

1 BACKGROUND

Cancer is the leading cause of death and disability

throughout the world, especially in women

(Ginsburg et al., 2016). Cervical cancer that strikes

women should be suppressed by conducting primary

and secondary prevention (Febriani, 2016). Cervical

cancer prevention efforts in Indonesia has still not

given priority to women of childbearing age.

Women have not made efforts to prevent cervical

cancer. This is related to social and cultural factors,

hereditary habits, lack of resources, economic

factors, and inadequate health care facilities

(Ompusunggu & Hill, 2011). The government has

issued a policy on the prevention and early detection

of cervical cancer by using Visual Inspection with

Acetic Acid (VIA). However, some studies suggest

that few women know about the risks and early

detection of cervical cancer (Rosser et al., 2015).

Cervical cancer is still the fourth ranked

affecting women around the world with 527 624

women each year contracting the disease, and 265

672 deaths as a result (Kessler, 2017). There are an

estimated 40,000 new cases of cervical cancer in

Indonesia each year. Indonesia has the highest

number of sufferers of cervical cancer at

approximately 36%. The East Java Province ranked

first for most cases of cervical cancer with a figure

of 21 313 (Ministry of Health, 2015). Data

Lamongan in 2016, positive IVA test data for 169

people, a Pap smear grade II/ III/ IV of 631/8/2 than

2,423 people were examined by the age of 30-50

years (Department of Health, 2016). PHC Data

Lamongan 2016 positive

VIA test data by 73 and the

data pap smear as much as 22 class 1 and class 2 as

many as 65 of the 219 people who checked in with

the number of women of childbearing age by 12 996

people. The Health Promotion Model

by Nola J

Pender focuses on an individual's ability to maintain

its health with the belief that it is better to act to

prevent disease and attempt an action that leads to

the improvement of the condition (Alligod, MR &

Tomey, 2006). Interpersonal factors are sourced

from the family and this group of people is one of

the factors that influences the behavior of women

regarding Pap Smears (Mouttapa et al., 2016).

Situational factors related to access or service may

inhibit or support the behavior of cancer prevention

(Chigbu, Onyebuchi, Ajah, & Onwudiwe, 2013;

Kim et al., 2012). The study (Armini, Kurnia, &

44

Armini, N., Fauziningtyas, R. and Prastiwi, A.

Correlation of Interpersonal Factors, Situational with Cervical Cancer Prevention in Woman of Childbearing Age.

DOI: 10.5220/0008320200440050

In Proceedings of the 9th International Nursing Conference (INC 2018), pages 44-50

ISBN: 978-989-758-336-0

Copyright

c

2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Hikmah, 2016) based on the Health Promotion

Model demonstrates that good personal factors

enhance efforts to prevent cervical cancer. It is

important to follow interpersonal factors and

situational analysis to prevent cervical cancer in

women of childbearing age.

2 METHODS

This study used the Desktriptif-analytic design:

Cross-sectional approach. The population of this

study comprised of 271 people. Samples were taken

from 159 people. The sampling technique used in

this study was probability sampling with simple

random sampling. Independent variables in this

study were interpersonal factors (family, peers, and

health workers) and situational (choice, demand

characteristics, and environment). The dependent

variables in this study are the primary and secondary

preventions of cervical cancer in women of

childbearing age. This study used a questionnaire

instrument. This questionnaire, relating to

interpersonal factors, associated domain suggestions

regarding cervical cancer prevention, social support

that comes from family, peers, and health workers,

and the influence of others who are already taking

steps to prevent cervical cancer. The questionnaire

contained 12 closed questions requiring yes and no

answers. The situational factors associated with the

prevention of cervical cancer were the level of

participation of people living around women of

childbearing age in the prevention of cervical

cancer, the environmental conditions for the

prevention of cervical cancer which contained three

questions with a choice of yes and no answers. The

questionnaire investigated cervical cancer

prevention efforts that have been conducted,

containing nine questions with the possible answers

‘never’, ‘rarely’, and ‘frequently’. The research was

conducted in Puskesmas Lamongan in June–July

2017. The results were analyzed using Spearman's

Rho test with significance level α ≤ 0.05.

3 RESULT

Based on reproductive history, results show that

most respondents had been pregnant <3 times at 110

respondents (69.2%). Most respondents used birth

control; a small proportion were not using

contraception. Most respondents were married at

149 respondents (93.7%), while there were 10

(6.3%) respondents who had never married or were

widowed. The most commonly used contraceptive

was the injection at 92 respondents (57.9%).

Respondents who had used family planning within a

period of <5 years and 5–10 years, respectively, was

47 respondents (29.6%). Regarding the respondents’

age when first experiencing sexual intercourse, 140

respondents (88.1%) were >18 years. The number of

respondents that already knew about cervical cancer

was 107 respondents (67.3%).

There were 37 respondents (23.3%) that had

already done tests, i.e. IVA /Pap smear, while 122

respondents (76.7%) had not done these tests. There

were only two respondents (1.3%) who had been

given the HPV vaccine; this was due to a health pr

program in the workplace.

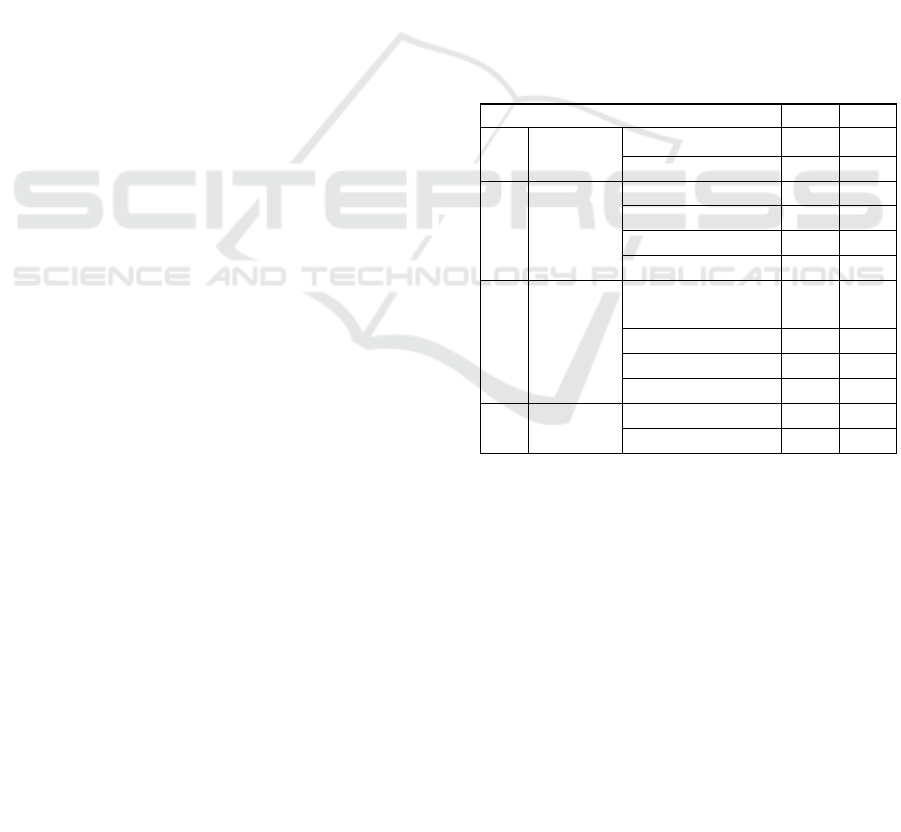

Table 1: Demographic data of respondents (n = 159)

No Demographics f %

1 Age 18–35 years 75 47.2

36–49 years 84 52.8

2 Education Elementary school 17 10.7

Junior high school 23 14.5

Senior high school 85 53.5

College 34 21.4

3 Work Government

officials

6 3.8

Private employees 32 20.1

Traders 23 14.5

Housewives 98 61.6

4 Family

income

<Rp.1.702.780 67 42.1

> Rp.1.702.780 92 57.9

Correlation of Interpersonal Factors, Situational with Cervical Cancer Prevention in Woman of Childbearing Age

45

As many as 78 respondents (49.1%) had low

interpersonal factors and only 37 respondents

(23.3%) were in the high category. Respondents

with situational factors in the medium category were

54 respondents (34%), while 52 respondents

(32.7%) belonged to the higher category. Sufficient

cervical cancer prevention efforts indicated a high

number of 136 respondents (85.5%).

For women of childbearing age, the prevention

of cervical cancer in the ‘sufficient’ category

indicates that 58 people (36.5%) have low

interpersonal relationships. According to the results,

42 people (26.4%) have medium interpersonal

relationships, and only 36 people (22.6%) have high

interpersonal relationships. However, one

respondent (0.6%) showed that a lower level of

cervical cancer prevention efforts proved to

demonstrate high interpersonal relationship factors.

The results from the Spearman rho p = 0.000 H1

indicate that there is a relationship between

interpersonal factors and the prevention of cervical

cancer in women of childbearing age. R = 0.299

indicates an insignificant relationship between the

variables of interpersonal factors and prevention of

cervical cancer in women of childbearing age.

The statistical test results from the Spearman

Rho p = 0.000 H1 accepted that there is a

relationship between situational factors and the

prevention of cervical cancer in women of

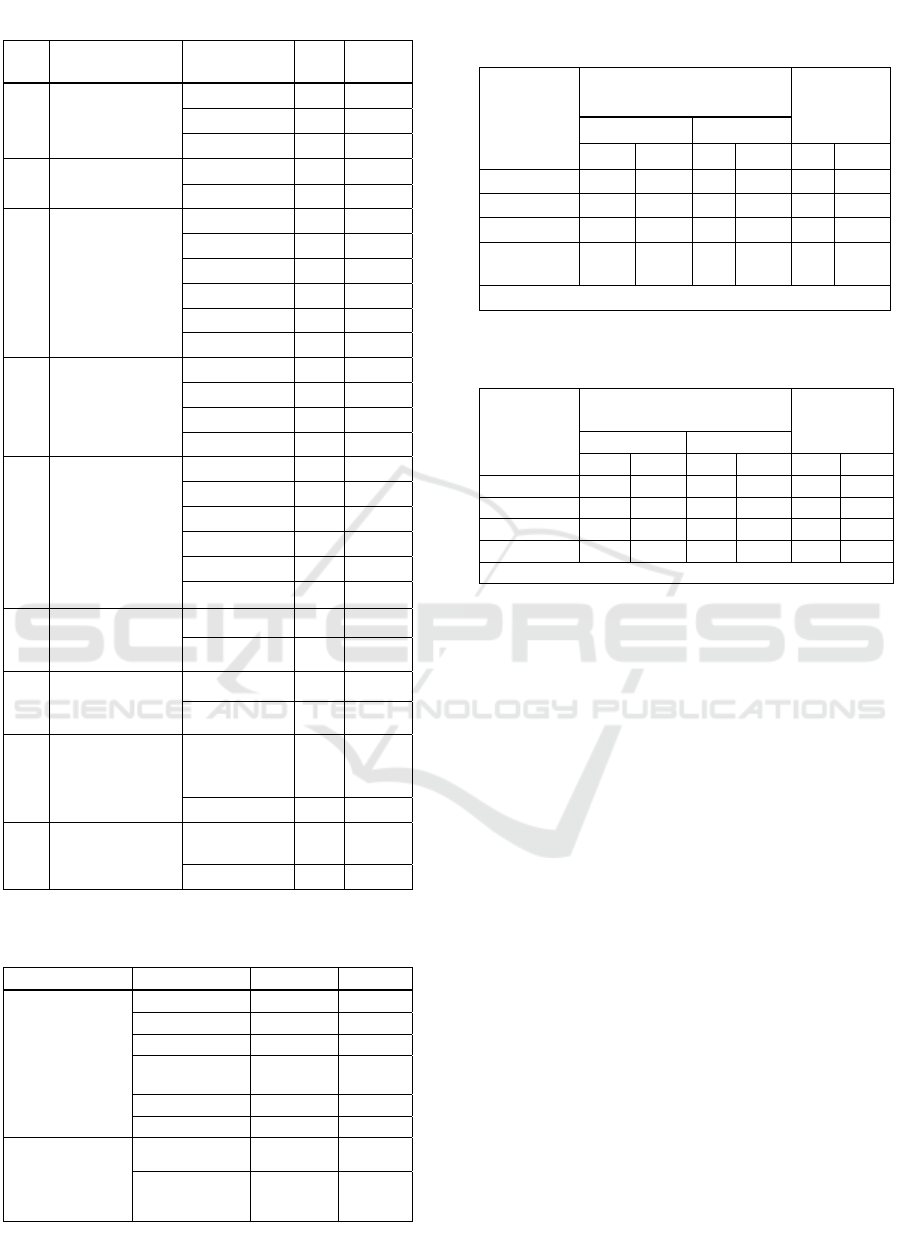

Table 2: Reproductive history (n = 159)

No Characteristics Criteria f %

1. Pregnant

experience

None 7 4.4

<3 times 110 69.2

≥3 times 42 26.4

2. Marital Status married 149 93.7

widowed 10 6.3

3. History of

contraception

used

None 32 20.1

1 type 92 57.9

2 type 26 16.4

3 type 6 3.8

4 type 2 1.3

5 type 1 0.6

4. Period of

contraception

used

None 32 20.1

<5 years 47 29.6

5–10 years 47 29.6

>10 years 33 20.8

5. Type of

Contraception

None 32 20.1

Injection 87 54.7

Oral 21 13.2

Implant 6 3.8

IUD 9 5.7

Tubectomy 4 2.5

6. The first

sexual

intercourse

≤ 18 years 19 11.9

>18 years 140 88.1

7. Knowledge

about cervical

cance

r

Not yet 52 32.7

Knows 107 67.3

8. Assessment

IVA/Pap

Smea

r

Not yet 122 76.7

Yes 37 23.3

9. The HPV

vaccine

Not yet 157 98.7

Yes 2 1.3

Table 3: Interpersonal, situational, and prevention

factors (n = 159)

Variable Criteria f %

Interpersonal

Factors

Low 78 49.1

Mediu

m

44 27.7

Hi

g

h 37 23.3

Situational

Factors

Low 53 33.3

Mediu

m

54 34

High 52 32.7

Cervical

cancer

prevention

efforts

Insufficient 23 14.5

Sufficient 136 85.5

Table 4: Interpersonal relationship factors in the

prevention of cervical cancer (n = 159)

Interperso

nal Factor

Cervical cancer

prevention efforts

Total

Insufficient Sufficient

f % f % ∑ %

Low 20 12.6 58 36.5 78 49.1

Medium 2 1.3 42 26.4 44 27.7

High 1 0.6 36 22.6 37 23.3

Total 23 14.5 13

6

85.5 15

9

100

Spearman rho p = 0.000 r =0.299

Table 5: Relationship of situational factors and the

prevention of cervical cancer (n = 159)

Situational

Factor

Cervical cancer

p

revention efforts

Total

Insufficient Sufficient

f % f %

∑

%

Low 14 8.8 39 24.5 53 33.2

Mediu

m

8 5.0 46 28.9 54 34

Hi

g

h 1 0.6 51 32.1 53 32.7

Total 23 14.5 136 85.5 159 100

S

p

earman rho

p

= 0.000 r =0.283

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

46

childbearing age. R = 0.283 showed that variables in

situational factors and the prevention of cervical

cancer in women of childbearing age have an

insignificant relationship.

4 DISCUSSION

There is a relationship between interpersonal factors

and the prevention of cervical cancer in women of

reproductive age with low levels of relationships in a

category. Most respondents have interpersonal

factors in the low category, but in cervical cancer

prevention efforts in the behavior of respondents is

sufficient. Primary prevention is a healthy behavior

that is generally carried out in everyday life, while

secondary prevention efforts such as IVA

examinations/Pap tests are not done immediately.

Most respondents were educated past high school or

its equivalent, at colleges, or were housewives. A

total of 23 respondents were housewives whose

distance from other houses was great, so the degree

of socialization of such individuals was less and

respondents only gained support from family who

lived at home but did not receive support from

others, such as neighbors or posyandu groups.

According to research by Torres et al. (2013)

communication between group members positively

and negatively affects the screening, encouragement,

and discussion of health problems and can

subsequently influence health-seeking behavior,

causing lower interpersonal factors for prevention

efforts.

Interpersonal factors that are the highest in this

study lie in the domain of social support relating to

family support in the prevention of cervical cancer.

Social support comes from a family able to provide a

positive influence, but the influence of others who

have less impacts prevention efforts. Domain social

support relates to the help given by the family for

the prevention of cervical cancer; husbands are

especially important in influencing the decisions

made by wives or other family members to reduce

the risk of cervical cancer. Some respondents were

health workers who had high interpersonal factors

and can provide information about cancer prevention

efforts.

Interpersonal factors, with the lowest influence

on others who are already making efforts to prevent

cervical cancer, are related to family members who

have previously been tested using IVA /Pap smear.

There were 61 respondents that stated they have

family members who already carry out secondary

prevention and many family members of

respondents who have not done tests using an IVA

/Pap smear.

Regarding marital status, most (149)

respondents are married and the participants’

husbands work as private employees and civil

servants, which facilitates communication between

them. Most husbands can provide support after

knowing the results of the IVA test program (Chigbu

et al., 2013). Families can contribute to the

prevention of cervical cancer by providing support

and motivation (Fallahi, Shahrbabaki, Hashemian, &

Kahanali, 2016). Family support, especially from

female relatives, provides encouragement and

motivation for individuals to perform a pap smear

test (Madhivanan, Valderrama, Krupp, & Ibanez,

2015). Prevention efforts that are sufficient in the

region are supported by the regions' existing

additional service for cervical cancer prevention

conducted by health workers. These are supported

by midwives and assisted by volunteer mothers at

the time of commemorating the cancer world with

lectures. According to research by Rosser, Njoroge

and Huchko (2015), educational interventions to

improve knowledge about cervical cancer can

improve prevention efforts. A total of 140

respondents had sexual intercourse at age >18 years

and 110 respondents have been pregnant <3 times,

reducing the risk of cervical cancer. Being married

and pregnant at an early age means the risk is ≥ 3

times the risk, increasing the incidence of HPV

infection and cervical cancer (Kessler, 2017).

There are several reasons that the 58 respondents

with low interpersonal factors, who make sufficient

effort for the prevention of cervical cancer. These

respondents have the notion that a pap smear

examination is only done when there is a complaint

around the pubic area. Respondents think healthy

conditions do not need to be checked. A total of 107

respondents know about cervical cancer but do not

yet understand fully the information. Thirty-seven

respondents have already done IVA/Pap smear tests,

but the prevention of cervical cancer by respondents

making sufficient efforts rarely pay attention to the

current state of stress and the fact that they rarely

slept for more than eight hours. A total of 37

respondents have already done IVA/Pap smear tests.

This is powered by age, of which most of the

respondents were aged between 21 and 49 years.

According to research by Hajializadeh et al., (2013)

the age range of 21–49 years is associated with Pap

smear test completion.

There were 36 respondents who had a high

degree of interpersonal factors and prevention.

Counseling by health officials and information from

Correlation of Interpersonal Factors, Situational with Cervical Cancer Prevention in Woman of Childbearing Age

47

neighbors who have used the IVA/Pap smear tests

for cervical cancer encourages the respondents to

maintain health so that women of childbearing age

can take steps to prevent cervical cancer early.

Neighboring women can provide a source of social

support for healthcare associated with a Pap smear

examination (Luque, Opoku, Ferris, & Guevara

Condorhuaman, 2016). Level of education also

motivates respondents to take precautions; as many

as 85 respondents were educated past high school or

equivalent and 34 were college educated. Education

has a positive impact on the perception of cervical

cancer in relation to the HPV vaccine (Kwan, Tam,

Lee, Chan, & Ngan, 2011). Levels of education, at

high school level or equivalent, encourage people to

receive new knowledge (Vamos, Calvo, Daley,

Giuliano, & López Castillo, 2015).

Two respondents had the HPV vaccine because

they had a family history of cervical cancer and

experienced reproductive problems. This was

supported by the family income >Rp.1,702,780. The

respondents’ husbands worked as civil servants.

Respondents’ prevention efforts were in the

‘sufficient’ category because many respondents

carried out primary prevention and behavior in

everyday life. Secondary prevention of cervical

cancer is to do tests such as IVA /Pap smear, but

these are rarely done by the respondents; only 37

respondents conducted the IVA/Pap smear tests.

There were respondents who had a low

interpersonal factors but cervical cancer prevention

efforts because respondents obtain information from

mass media and the Internet. Mass media is a useful

tool for encourage testing IVA/Pap smear (De Vito

et al., 2014).

There is a relationship between situational

factors and the prevention of cervical cancer in

women of childbearing age. Situational factors that

have a relationship in this study relate to of

environmental conditions for the prevention of

cervical cancer in the region where there are

community health clinics and health centers within

the region tersebuat Lamongan ± 2 km. Factors that

influence is less domain the level of participation of

people living around women of childbearing age in

the prevention of cervical cancer because some

respondents were confused when filling out

questionnaires on these domains because they did

not know many women who had already had the

IVA/Pap smear test.

Some respondents already knew about cervical

cancer prevention program. Some were told by

family members, or volunteers when filling out the

questionnaire. Situational factors were included in

the low category because most respondents hesitated

when answering whether neighbors or mothers in the

residential area already had IVA/Pap smear tests.

There were 51 respondents who had sufficient

situational factors and prevention. This was because

respondents knew that there are programs such as

the IVA test/Pap smear close to the residence of

respondents. When experiencing reproductive

problems, respondents immediately went to visit the

healthcare center, but inside the house, there are

family members who smoke, thus affecting cervical

cancer prevention efforts. Healthcare providers can

influence and educate the reduction of incidences of

cervical and breast cancer (Schoenberg, Kruger,

Bardach, & Howell, 2013). The higher the

situational factors, the higher the prevention of

cervical cancer. Improved healthcare facilities will

have a major impact on the prevention of cervical

cancer (Rosser et al., 2015).

Some respondents (53) hesitated when filling in

the level of participation of people living around

women of childbearing age in the prevention of

cervical cancer. Some respondents were confused

when filling out the questionnaires in these areas

because they did not know the information regarding

women of childbearing age in the neighborhood that

had taken the IVA/Pap smear tests.

There were 39 respondents that had low

situational factors and take steps to prevent cervical

cancer in the ‘sufficient’ category. Making an effort

to prevent cervical cancer is a behavior that is often

performed in daily life but lower situational factors

of respondents means that if there are health

problems that are not life-threatening, they do not

need to check with the health clinic and are only

given herbal medicine. When experiencing vaginal

discharge or itching in the area around the genitals,

respondents did not check into the health clinic

because of their perception of it being a natural

condition. Beliefs, behaviors, and stressors affect

individuals in the prevention of cervical cancer

(Daley et al., 2011).

Regarding available options in the prevention of

cervical cancer, there were 96 respondents that never

check their health with the health services. Some

respondents had health problems related to

reproductive issues. Types of birth control used by

the respondents, as many as 87 types of injections

and a history of contraceptive use many types of

birth control use 1 as much as 92 response.

Injections have side effects if used for a long time.

Forty-seven respondents used contraception <5 years

and 47 respondents used contraception for 5–10

years. Hormonal contraception can cause adverse

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

48

effects on reproductive disorders and weight-gain

issues, pushing the respondents to make visits to the

healthcare service (Simmons & Edelman, 2016;

Wiebe, Brotto, & MacKay, 2011).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Most women of childbearing age have low

interpersonal factors; the family/husband, neighbors,

close friends and health workers still offer little

support in the prevention of cervical cancer in

Puskesmas, Lamongan. Various situational factors

show almost an equal number of available options:

the level of community participation and

environmental conditions. Cancer prevention efforts

are mostly in the category of pretty. Almost all have

done to prevent cervical cancer primary prevention

of secondary, but many are not doing. Low

interpersonal factors that will inhibit cancer

prevention efforts. Situational factors are almost

balanced by the options available: the level of

community participation and environmental

conditions will support efforts to prevent cervical

cancer in women of childbearing age, in the working

area of Puskesmas Lamongan.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The researchers would like to thank the Faculty of

Nursing, Universitas Airlangga for the publication

and all the women of childbearing age who devoted

their time and willingness to participate.

REFERENCES

Alligod, M.R & Tomey, A. (2006). Nursing Theorist and

Their Work. 6th. Missouri: Mosby.

Chigbu, C. O., Onyebuchi, A. K., Ajah, L. O., &

Onwudiwe, E. N. (2013). Motivations and preferences

of rural Nigerian women undergoing cervical cancer

screening via visual inspection with acetic acid.

International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics,

120(3), 262–265.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.10.011

Daley, E., Alio, A., Anstey, E. H., Chandler, R., Dyer, K.,

& Helmy, H. (2011). Examining barriers to cervical

cancer screening and treatment in florida through a

socio-ecological lens. Journal of Community Health,

36(1), 121–131. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-010-

9289-7

De Vito, C., Angeloni, C., De Feo, E., Marzuillo, C.,

Lattanzi, A., Ricciardi, W., … Boccia, S. (2014). A

large cross-sectional survey investigating the

knowledge of cervical cancer risk aetiology and the

predictors of the adherence to cervical cancer

screening related to mass media campaign, 2014.

http://doi.org/10.1155/2014/304602

Dinkes. (2016). Rekapitulasi deteksi dini kanker payudara

dan kanker leher rahim puskesmas se-kabupaten

Lamongan. Lamongan.

Fallahi, A., Shahrbabaki, B. N., Hashemian, M., &

Kahanali, A. A. (2016). The needs of women referring

to health care centers for doing pap smear test, 19(6).

Febriani, C. A. (2016). Faktor-faktor yang berhubungan

dengan deteksi dini kanker leher rahim di kecamatan

gisting kabupaten tanggamus lampung, VII, 228–237.

Ginsburg, O., Bray, F., Coleman, M. P., Vanderpuye, V.,

Eniu, A., Kotha, S. R., … Message, U. S. G. (2016).

The global burden of women’s cancers: a grand

challenge in global health. The Lancet, 0(0), 743–800.

http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31392-7

Hajializadeh, K., Ahadi, H., Jomehri, F., & Rahgozar, M.

(2013). Psychosocial predictors of barriers to cervical

cancer screening among Iranian women: the role of

attachment style and social demographic factors.

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 54(4),

218–22.

Kemenkes. (2015). Stop Kanker. infodatin-Kanker.

Jakarta.

Kessler, T. A. (2017). Cervical Cancer: Prevention and

Early Detection. Seminars in Oncology Nursing.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2017.02.005

Armini, N. K. A., Kurnia, I. D., & Hikmah, F. L. (2016).

Personality Factor , Self Efficacy and Prevention of

Cervical Cancer among Childbearing Age Women.

Jurnal Ners, 11(2), 294–299.

Kim, Y.-M., Ati, A., Kols, A., Lambe, F. M., Soetikno, D.,

Wysong, M., … Lu, E. (2012). Influencing Women’s

Actions on Cervical Cancer Screening and Treatment

in Karawang District, Indonesia. Asian Pacific Journal

of Cancer Prevention, 13(6), 2913–2921.

http://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.6.2913

Kwan, T. T. C., Tam, K. fai, Lee, P. W. H., Chan, K. K.

L., & Ngan, H. Y. S. (2011). The effect of school-

based cervical cancer education on perceptions

towards human papillomavirus vaccination among

Hong Kong Chinese adolescent girls, 84(1), 118–122.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.018

Luque, J. S., Opoku, S., Ferris, D. G., & Guevara

Condorhuaman, W. S. (2016). Social network

characteristics and cervical cancer screening among

Quechua women in Andean Peru, 16(1).

http://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2878-3

Madhivanan, P., Valderrama, D., Krupp, K., & Ibanez, G.

(2015). Family and cultural influences on cervical

cancer screening among immigrant Latinas in Miami-

Dade County, USA, 18(6), 710–722.

http://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1116125

Mouttapa, M., Park Tanjasiri, S., Wu Weiss, J., Sablan-

Santos, L., DeGuzman Lacsamana, J., Quitugua, L.,

… Vunileva, I. (2016). Associations Between

Women’s Perception of Their Husbands’/Partners’

Correlation of Interpersonal Factors, Situational with Cervical Cancer Prevention in Woman of Childbearing Age

49

Social Support and Pap Screening in Pacific Islander

Communities. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health,

28(1), 61–71.

http://doi.org/10.1177/1010539515613412

Ompusunggu, F., & Bukit, E. K. (2011). Karkteristik,

hambatan wanita usia subur melakukan pap smear di

puskesmas kedai durian, 20–24.

Rosser, J. I., Njoroge, B., & Huchko, M. J. (2015).

Knowledge about cervical cancer screening and

perception of risk among women attending outpatient

clinics in rural Kenya. International Journal of

Gynecology and Obstetrics, 128(3), 211–215.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.09.006

Schoenberg, N. E., Kruger, T. M., Bardach, S., & Howell,

B. M. (2013). Appalachian women’s perspectives on

breast and cervical cancer screening., 13(3), 2452.

Simmons, K. B., & Edelman, A. B. (2016). Hormonal

contraception and obesity. Fertility and Sterility,

106(6), 1282–1288.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1094

Torres, E., Erwin, D. O., Treviño, M., & Jandorf, L.

(2013). Understanding factors influencing Latina

women’s screening behavior: A qualitative approach,

28(5), 772–783. http://doi.org/10.1093/her/cys106

Vamos, C. A., Calvo, A. E., Daley, E. M., Giuliano, A. R.,

& López Castillo, H. (2015). Knowledge, Behavioral,

and Sociocultural Factors Related to Human

Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Cancer

Screening Among Inner-City Women in Panama.

Journal of Community Health, 40(6), 1047–1056.

http://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-015-0030-4

Wiebe, E. R., Brotto, L. A., & MacKay, J. (2011).

Characteristics of Women Who Experience Mood and

Sexual Side Effects With Use of Hormonal

Contraception. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Canada, 33(12), 1234–1240.

http://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35108-8

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

50