Can Humor Competence Be Taught?

Tran Thi Ai Hoa

Khanh Hoa University, Viet Nam

Keywords: Humor, Competence, Joke, Appreciation, Theory

Abstract: Humor competence is an important aspect of sociolinguistics for EFL learners to understand and appreciate

humor. Differences in language uses, cultures and society can cause obstacles for achieving humor

competence. However, it is necessary to define exactly what knowledge is necessary to a non-native speaker

to process humor in L2 (Attardo, 2010). This paper is concentrated on an application of Semantic theory of

humor (Attardo and Raskin, 1991), scalar implicature of unqualified humor support to humorous texts(Hay,

2001) and pragmatic competence Bachman (1990) for formulating EFL learners’ ability to appreciate

humor in English jokes.

1 INTRODUCTION

The term “competence” is defined as “the capacity,

skill or ability to do something correctly or

efficiently, or the scope of a person or the scope of a

person’s or a group’s ability or knowledge”. More

clearly, it is “the quality of being competent;

adequate; possession of required skill, knowledge,

qualification, or capacity”. Thus, one’s humor

competence is that someone is qualified at

recognizing, understanding and appreciating the

humor in humorous texts and more than that they

can produce humor.

However, understanding and recognizing humor

seems difficult for EFL learners in some non-native

contexts in which English is not used out of the

classroom since what one culture can laugh at

(superiority), laugh about (incongruity) or laugh in

spite of (relief) may vary widely from one country to

another ( Geddert cited in Deneire, 1995). Actually,

differences in language uses, cultures and society

can cause obstacles for learners in trying to achieve

humor competence. Attardo (2010) states that it is

important to specifically determine what knowledge

is necessary to a non-native speaker to process

humor in second language.

2 HUMOR AND SENSE OF

HUMOR

What is humor? In Ermida (2008)study, the term

“humor” is derived from the Latin word “humor”

which referred to the four basic body fluids such as

blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. At that

time, it was believed that good health depended on

the balance of these four fluids in one’s body.

Diseases or bad temperaments occurred for the

incorrect mixture or disorder of these fluids. A

person was recognized to be in good health when

these fluids were balanced. In the 16

th

century in

England, humor represented a prevailing mood

quality which could be positive (good humor) or

negative (bad humor). Thus, there goes a saying “To

be in a good humor” which means that a person is in

a cheerful mood (Beermann and Ruch, 2009).

Besides, humor was related to a virtue when it

contributed to tolerance and benevolence (Beermann

and Ruch, 2009). During the 19

th

century, humor

was emanated as an essential virtue with an

association of a strong and optimistic character

(Martin, 2007).

Today, humor is preferable to any place and is

settled as a valued characteristic in anyone who has

a sense of humor. Moreover, humor is an umbrella

term that covers all the synonyms and overlapping

meaning of humor and humor-related subjects not

just in neutral and positive format as comic, ridicule,

irony, mirth, laughable, jolly, funny, ludicrous,

merry, etc. but on negative forms as sarcasm, satire

and ridicule (Attardo and Raskin, 1991). The 20

th

and 21

st

centuries have seen a series of studies on

humor topic towards positive outcomes of using

humor in health, education and the workplace.

The term "sense of humor" is understood with

reference to both humor creation and humor

Ai Hoa, T.

Can Humor Competence Be Taught?.

DOI: 10.5220/0008218900002284

In Proceedings of the 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference (BELTIC 2018) - Developing ELT in the 21st Century, pages 389-396

ISBN: 978-989-758-416-9

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

389

appreciation, which is so all-inclusive and highly-

prized that (Edwards, 1997) remarks "”He has a

grand sense of humor” is also synonymous with “He

is intelligent, he's a good sport, and I like him

immensely”” (Edwards, 1997). Thus, when a person

is said to have sense of humor, he firstly can laugh at

things he finds to be funny, laugh a great deal and

easy to be amused, and secondly he can tell funny

stories and amuse other people (Edwards, 1997).

However, not all people have sense of humor always

laugh at humor and vice versa. A person who has

little sense of humor can appreciate and laugh at a

comic because humor appreciation is an element of

the mind while sense of humor is mostly in favor of

in-born (Edwards, 1997). Therefore, it can be stated

that sense of humor relates to human behavior and is

part of humor in terms of ability. Then what part of

humor can be appreciated and what knowledge to be

developed for the ability?

3 HUMOR APPRECIATION

It is complicated to classify humor because there is

no universal theoretical framework which can

satisfactorily account for all types of humor and the

functions that they serve. However, humor has its

classification. Humor can be either verbal or non-

verbal, a subjective experience or serve

communicative purposes, draw upon common

everyday reality or consist of fiction and

imagination, charm or attack, be created

spontaneously or be used as a well-prepared

technique of personal and professional interaction

and even can be a simple joke told among friends or

amount to the sophistication of Shakespeare’s plays

Ermida (2008). Actually, jokes have the

characteristics of verbal humor (VB) which is

related with words, sentences, texts and discourse. A

joke is made up of grammatically well-formed

sequence of words and postulates some conventional

linguistic analysis of text and make statements

involving concepts such as “words”, in spite of the

fact that it sometimes goes beyond the convention

labeling needed for pure linguistic purposes (Ritchie

et al., 2013).

A peculiar element of contrast is symbol of the

joke. Fischer (1889) proposes the characteristics of

verbal humor be seen as a playful judgment which is

merely a force which is necessarily used both to

imagine objects and clarify them. The force can

illustrate thoughts or more clearly it helps produce a

comic contrast. Joke contains a contrast, but not

between ideas. It is the contradiction between the

meaning and meaninglessness of the words. In fact,

joking is merely playing with ideas, at least two

which are distinct and irreconcilable but self-

consistent (Fischer, 1889). A typology of verbal

humor in terms of humorous techniques includes

two properties: (1) Condensation; and (2)Double

Meaning or displacement,“a change in the way of

considering something” (Freud, 1974, p. 74). It is

proven to be equivalent to the incongruity/ contrast

theory that “the pleasure in a joke arising from a

“short circuit” …the two circles of ideas that are

brought together by the same word” (Freud, 1974, p.

110), which means one circle of one idea to another

and being apart are “circumlocution” for contrast.

Actually, the contrast is an alternative element of

the incongruity theory which is among the three

theories of humor (Attardo and Raskin, 1991).

Incongruity is the core of all humor experiences. It

contains something unexpected, out of context,

inappropriate, unreasonable, illogical, exaggerated,

and so forth and serves as the basic vehicle for the

humor (Freud, 1974). In other words, incongruity is

regarded as the prerequisite of the humor and the

humorous effect arrives when the incongruity is

interpreted. Martin (2007) says "the humorous effect

comes from the listener's realization and acceptance

that s/he has been led down the garden path..."

Freud (1974) explains the incongruity that humor

is created out of “a conflict between what is

expected and what actually occurs in a joke, the

most obvious feature of much humor is an ambiguity

of double meaning, deliberately misleading the

audience, and is a punch line". (Freud (1974) says

"Humor arising from disjointed, ill-suited pairings of

ideas or situations or presentations or ideas or

situations that are divergent from habitual customs

from the bases of incongruity." And more clearly,

Freud (1974) defines "Incongruity, associating two

generally accepted incompatibles; it is the lack of a

rational relation of objects, people, or ideas to each

other or to the environment." Ritchie et al. (2013)

concretely describes the way the incongruity-

resolution concretely works in case of a joke

formation. A joke consists of a "set-up" and a

"punch line". The punch line conflicts with a

perceived interpretation of the set up. The punch line

can be resolved with an alternative interpretation of

the set up. Also, Attardo (2010) confirms that to

create humor, the incongruity must be resolved.

Similarly, the process of appreciating the

humorous effect of a joke is to experience two

phases. (Freud, 1974) suggests a model highlighting

the role of incongruity and resolution in the

generation of humorous effect. It consists of two

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

390

stages in which the key of humor lies in the initial

one in which an incongruity is detected by the

hearer. Then while the hearer tries to solve the

incongruity or make sense of the joke, he or she will

search for a cognitive rule that reconciles the

incongruous part, and upon finding a resolution to

the incongruity, he or she will be relieved and

perhaps will also be humorously entertained (Martin,

2007, p. 64).

The process of perceiving and understanding in

this two stage model is a cognitive one and generally

agreed Beermann and Ruch (2009), but the way

resolution is achieved is various in different jokes.

Joke (2) is simply found the wife's utterance by the

end of the joke for its resolution. On other occasions,

the hearer has to "backtrack and choose another

interpretation (initially more unlikely and not as

relevant, but eventually correct) in order to realize

she or he has been fooled into selecting that initial

interpretation (the one initially relevant), and set

upon a different path of joke resolution". Thus, it is

not easy to understand the incongruity because it has

a level of difficulty in interpreting the language of

incongruity.

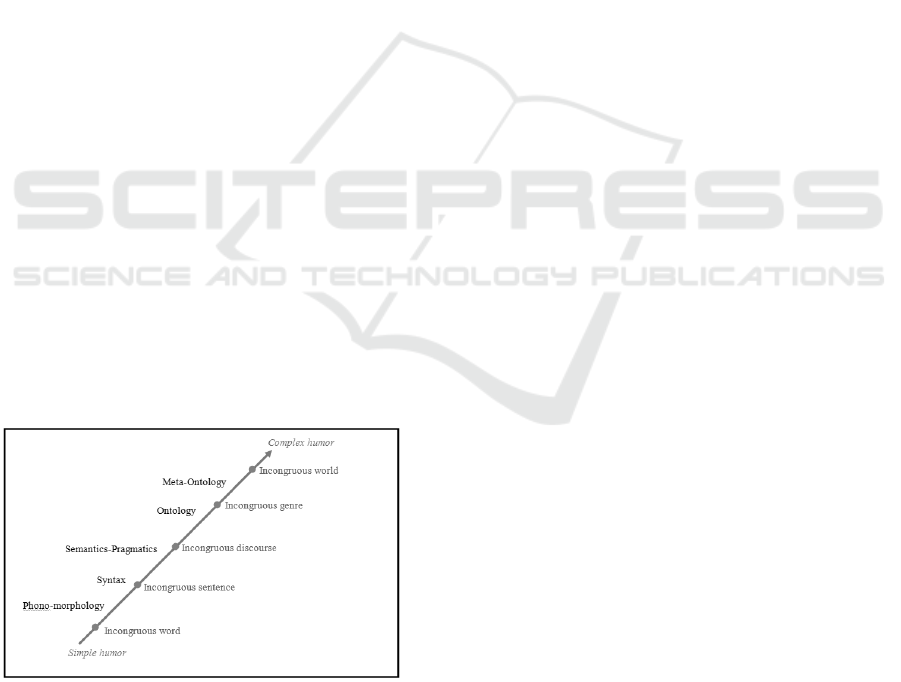

Obrst (2012) graphically depicts a spectrum of

the linguistic humor at a linguistic structural level

focused on the incongruity theory (Figure 1). Under

the incongruity theory, a linguistic structural level

comes up from a basis on sound or word, syntactic

attachment, sentence to higher grades as discourse,

genre, world etc. It is an incongruous generation

which is given by the humor provider and then

possibly understood by the humor consumer as

permitting anomalous interpretations. In order to

understand such above cognitive process, speakers,

especially EFL learners of L2 need to achieve humor

competence (Attardo, 2010).

Figure 1. Linguistic humor structure spectrum (Obrst,

2012).

4 COMPONENTS OF HUMOR

COMPETENCE

In order to appreciate humor in jokes a person has to

have humor competence because “the humor

competence would allow a given speaker to

recognize humor, just like a native speaker could

recognize a grammatical sentence, without being

able to explain why it was grammatical” (Attardo,

2010). Then, there appears to be one main

interaction between the joke audience and the

humorous text (the joke) which is divided into three

sub-correlations in the process of making sense of or

appreciating humor in English jokes.

At first, humor competence is considered in the

correlation between the joke audience’s linguistic

knowledge and the language of the joke, which leads

to a successful interpretation. Typically, Attardo and

Raskin (1991) Semantic Script Theory of Humor

proposes a semantic-pragmatic process of humor

manifestation. The so-called semantic Script-switch

trigger plays an important role in the operation of a

humorous text. It is a switch from a normally-

constituted text into a humorous script Attardo and

Raskin (1991) that makes up the joke. The contrast

of the two scripts, an incongruity between the two

induces a humorous effect, so jokes contain

elements of contrast as mentioned above or

ambiguities of different types (Obrst, 2012)

Attardo and Raskin (1991) defines humor

competence (HC) is “the ability of native speaker to

pass judgments as to the funniness of a text” in his

proposed semantic theory of humor with the aim at

formulating a set of conditions which are both

necessary and sufficient for a text to be funny. The

conditions for interpreting a joke text should be

ascertained between the reader and the writer of the

humorous message. Sequentially, the prerequisite for

a joke text to be funny is focused on the term of

“share” (Attardo and Raskin, 1991). They are

reader/hearer and the joke text writer/speaker who

have to share the knowledge of presupposition,

implicature of the ambiguity, the context, the

language and the structure of the text (Freud, 1974,

Attardo and Raskin, 1991, Ritchie et al., 2013).

Consider the following joke:

(1)In the dinner of a southbound

train, a honeymoon couple noticed two

nuns at another table. When neither

could decide what they should order

from the menu, the husband volunteered

to settle the question by asking the

nuns, who seemed to be enjoying their

meal very much.

Can Humor Competence Be Taught?

391

“Pardon me, Sisters,” he said,

pausing politely before the nuns’

table, “but would you mind telling me

your order?”

One of the nuns smiled at him. “Not

at all,” she said cheerfully. “We’re

Carmelites!”

(Attardo, 2010)

It is sure that reader/hearer cannot interpret joke

(1) when he/she does not satisfy the conditions for a

text to find it funny. The conditions are as follows.

The presupposition to be shared: Carmelite

nuns

An implicature to be interpreted by R/H:

order

A possible world to be recognized: Dining

on the train

Humor language occurring: speech act

joking (misunderstanding)

(Attardo and Raskin, 1991, p. 57)

In his semantic theory, Attardo and Raskin

(1991)) highlights the importance of linguistic

theory with two components of the “lexicon” and the

“combinatorial rules” that supply speakers with

knowledge of word meaning and sentence meaning

for complying with the requirements of detecting

and marking the source of ambiguity,

disambiguating a potentially ambiguous sentence in

a non-ambiguous linguistic or extralinguitic context,

interpreting implicatures where present and potential

implicatures wherever possible, discovering the

presuppositions of the sentence if any, and

characterizing the world in which the situation

described by the sentence takes place, in the aspects

pertinent to the sentence. In addition, the SSTH

represents a pragmatic process of humor expression

when there is a transfer from bona-fide into non-

bona fide communication. In the premise of the so-

called no-bona fide communication, humor is

created when jokes flouts Gricean Cooperative

principle and its maxims Grice (1991) and has its

own principles.

Later, Attardo and Raskin (1991) developed the

SSTH into the GTVH (General theory of verbal

humor), in which new elements of humor

competence are added, namely six knowledge

resources including (1) the Script opposition, (2) the

Local mechanism, (3) the Situation, (4) the Target,

(5) the Narrative strategy and (6) the language. That

means a speaker has to pass these if he/ she knows

the two different and opposite scripts of a joke, the

playful logic instrument of the opposition, the

contexts involving he objects, participants, places,

activities in joke-telling, the stereotypes or the butt

of the joke, type of the jokes, and information or

wording in jokes (Attardo, 2010). However, Attardo

and Raskin (1991) semantic theory just introduces

humor competence on the surface of linguistic

competence and semantic competence in relation

with words and sentences and rules, but there are no

other ideas on culture or society that supports to

develop humor competence. Chiaro (2006)

constitutes humor competence with three elements,

namely the linguistic, the socio-cultural and the

poetic which indicate respectively for (i) the ability

to understand the meaning of the words to be

signaled in a joke, (ii) the ability to identify the

social context or the cultural feature to be attached in

the joke and (iii) the ability to interpret or read the

figurative language to be embedded. The model

shows a strong social dimension of understanding

humor in jokes. Consider the following joke.

(2) Guess who quit smoking?

David Koresh. (Carrell, 1997)

Joke (2) is at first is a common type of question

and answer in the mode of bona-fide communication

Attardo and Raskin (1991) where there are smoking

people and it is normal when people stop smoking.

However, it is a real joke in the form of riddle. The

punch line “David Koresh” should force the

audience to reinterpret the question if he was a

smoker but then realize that the joke plays on

“smoking” that is the character Koresh is related

with a social event in America. If the audience

interprets the implicature in the punch line, the mode

of communication is changed (shifted) into non-

bona-fide communication. If the audience still sees

the question as a normal one, the communication

does not change. Then the joke text fails because no

humor can possibly result on the part of the audience

and that text can never get any level of humor

competence. And this takes place unconsciously.

(Carrell, 1997, p. 179) also suggests two main

factors to affect this failure: one is that the audience

is unfamiliar with the form of the joke text; and the

other is the audience is not in the possession of one

or more of the semantic scripts necessary to identify

and subsequently process the text as a joke, or both.

With joke (2), the problem is not at its structure,

but its content. The joke text hinges on the

knowledge of both David Koresh and the fire at the

Branch Davidian compound near Waco, Texas, on

April 19, 1993 (Carrell, 1997). The audience cannot

interpret the joke because they are not in the

possession of such script, the one which contains

that information. Simply they see the question and

answer are in bona-fide conversation because they

do not know who David Koestler is. Thus it can be

practically known that joke competence is the ability

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

392

to read the second script of the joke. And the

audience can be “equipped with more information

from the joke teller and endeavor to reprocess the

joke text through his or her joke competence”

(Carrell, 1997, p. 180). This creates a second

correlation between the joke audience’s style

reference and the language of the joke, which results

in either appreciation or non-appreciation (Carrell,

1997)

Hay (2008) has also proposed a similar point

when discussing humor support strategies. She talks

of qualified and unqualified humor support, of

which the latter involves a scalar implicature (where

“implicature” is taken to mean communicative

implication). The three implicatures are 1.

Recognition, 2. Understanding, and 3. Appreciation

(Hay, 2008), which is similar to Raju’s three

“mental operations” above. However, researchers

have wondered that when a joke is appreciated there

may be a neglect of being amused. Therefore, Hay

(2008) when discussing humor support strategies,

adds a fourth element of agreement into the three

implicatures discussed (recognition, understanding,

appreciation). That is, in such cases there is

dependence between appreciation and agreement.

Hence, she also notes that it is possible for someone

to be simultaneously offended and amused so that

they support the humor but express disagreement

e.g. ‘laughter followed by an explicit cancellation

such as “that’s cruel”. This appears an interaction

between joke audience’s attitudes and beliefs and the

content of the joke, which induces either

appreciation or offence. Integrating the model of

humor competence (Chiaro, 2006; Hay, 2008), it is

obviously seen that the knowledge to be essential for

appreciating humor in English jokes is acquired in a

system of competence: linguistic-semantic

competence, socio-cultural competence and poetic

competence.

5 HUMOR COMPETENCE

INTERFACED IN PRAGMATIC

COMPETENCE

Pragmatic competence (PC) is defined as “the ability

to use language effectively in order to achieve a

specific purpose and to understand language in

context” (Thomas, 1983), “the ability to

communicate your intended message with all its

nuances in any socio-cultural context and to interpret

the message of your interlocutor as it was intended”

(Fraser, 1999). Pragmatic competence is a

subcomponent to the more level of communicative

competence (Fraser, 1999 ; Bachman, 1990).

Bachman (1990) propose an overarching model,

named "Communicative language ability" which

consists of both the knowledge and the capacity for

executing that competence in appropriate,

contextualized communicative language use

(Bachman, 1990, p. 84). This model contributes to

broadening the concept of communicative

competence, which afterwards is employed

extensively in the second language learning and

assessing and covers the model of communicative

competence. It entails two major dimensions:

organizational competence and pragmatic

competence (Bachman, 1990, p. 84-87).

Organizational competence consists of grammatical

competence and textual competence and pragmatic

competence encompasses two main abilities of

illocutionary and sociolinguistic competence.

It can be seen that components of Bachman’s

language competence drive for joke competence and

humor competence comprising linguistic-semantic

competence, socio-cultural competence and poetic

competence. Deniere (cited in Baron-Earle, 1995)

points out that “well-developed communicative

competence implies humor competence, and vice-

versa”. He also stresses the language learners also

need to develop “a certain level of cultural

competence in the target language because a

language learner cannot appreciate the humor of that

language even if he/she is competent at the target

language (Bell, 2007). That is, the non-native

speaker needs to become acculturated in the culture

of the language she is learning if she ever hopes to

understand that speech community’s humor. Thus

pragmatic competence is essential for humor

competence because it provides knowledge of

pragmatic conventions to be acceptable and

knowledge of sociolinguistic conventions to be

appropriate for the language functions in a given

context both in competence and performance

(Bachman, 1990, p. 87-90).

Illocutionary competence, in Bachman (1990)

pragmatic competence, relates to the theory of

speech acts referring to utterance acts, propositional

acts, and illocutionary acts. These acts respectively

indicate “saying something”, “expressing a

prediction about something” and “the function

performed in saying something”. Additionally,

perlocutionary act is the effect of a given

illocutionary act on the hearer. Bachman (1990: 90)

clearly describes that to accomplish a success in

driving a meaningful utterance it is necessary to use

Can Humor Competence Be Taught?

393

illocutionary competence with a range of abilities as

follows.

a) To determine which of several possible

statements is the most appropriate in a

specific context.

b) To perform a propositional act which is

grammatically well-formed and

significantly.

c) To be able to be complied by non-language

competency factors

Sociolinguistic competence refers to the ability to

perform the language functions, mentioned above, in

appropriate ways for various language use contexts.

Sociolinguistic competence includes sensitivities to

language variety differences, to register or language

use variation within a variety, to naturalness or

native-like manner, to cultural references and figures

of speech. Of all the sensitivities such as the ones to

differences in dialect or variety, to differences in

register, and to naturalness which concern the

language performance, and especially the ability to

interpret cultural references and figures of speech

which is related with the interpretation of cultural

and figurative language. However, joke telling

means reciting jokes which is the lowest level of

humor production, so the ability to interpret cultural

references and figures of speech is taken as one

important element which is suitable with humor

interpretation as the key point of humor

appreciation.

Obviously, both humor interpreting and

producing holds responsible to illocutionary

competence and sociolinguistic competence.

Likewise, a person who wants to be able to interpret

the humor in jokes or tell jokes should be proficient

at pragmatic competence. He/she should be able to

perceive the humorous language of the joke, be

aware of the figurative and cultural styles in the joke

and agree with the humorous type of the joke text

for appreciating it. Actually, it can be stated that

humor competence is interfaced with pragmatic

competence in terms of appreciation and

performance with system of competence. This

system of competence is necessary for EFL learners

to develop their humor competence in the broad

communicative competence.

6 L2 HUMOR COMPETENCE CAN

BE TAUGHT AND STUDIED

Humor competence is viewed as part of overall

communicative competence, and this is “not

controversial” (Attardo, 2010). Researchers have

studies confirming that pragmatic competence can

be taught (Kasper, 1997). Now that pragmatic

competence is a component of the broad

communicative competence since communicative

action includes not only speech acts such as

requesting, greeting, apologizing, etc but also

participation in conversation, engaging in different

types of discourse, and sustaining interaction in

complex speech events. In such conversation,

speakers are able to promote their imaginativeness

and creativeness in their own environment for

humorous or esthetic purposes, where the value

derives from the way in which the language itself is

used such as telling jokes,… (Bachman, 1990).

Thus, it is sure that humor competence can be

taught.

L2 humor competence is hence needed to be

taught in the context of teaching English as a foreign

language. Firstly, humorous language helps enrich

learners variations of the English language used in

different geographic regions (Bachman, 1990).

Secondly, learners enhance their knowledge of

culture through cross-cultural studies because each

culture has its own set of values, norms, and

unwritten rules of what is appropriate in humor, and

these largely determine its content, target, and styles

(Freud, 1974). Thirdly, humor education helps

learners embody to the cognitive and mental theory

of learning. Lastly, sociolinguistics proposes that

true competence in a language is determined by the

learners’ ability to use language appropriately in the

needed contexts. This proposal would certainly

include the appropriate comprehension and

appreciation of tone variance within written

language as an essential part of academic

competence. Verbal humor of the characters in

humorous episodes which are analyzed reveals

important aspects in the definition of social identity

and originality (Matthews et al., 2006).

Many researchers have had studies on humor

competence in recognition, comprehension,

perception and appreciation and achieved positive

results. Martin (2007) investigated the problems of

understanding jokes in the English language and

explored about the advantages of English jokes to

improve reading comprehension for Thai Students.

Questionnaire containing five jokes was sent to fifty

subjects of English major and French major. The

jokes were taken from The Reader Digest Magazine

following some criteria concerning the length of

jokes, joke context, language complexity, and

variety of situations. The results show that the

students always read English jokes 2-3 times per

week and few read English jokes every day.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

394

Table 1: Studies on Humor Competence.

Study

Teaching

goal

Proficiency

Languages

Erin

Baldwin

2007

Jokes, film

clips,

cartoons

Doctoral

students

L2: English

Douglas

Wulf

2010

Joke

categories

Advanced

students

L2: English

Zsuzsann

a Schnell

2010

Jokes

Preschool

children

L2: English

Melody

Geddert

2012

Reading

materials

First-year

students

L2:

English,

Chinese,

Punjabi

Maria

Petkova

2013

Jokes

Advanced

students

L2: English

Richard

J.

Hodson

2014

Humorous

texts:

written and

spoken

(Numerous

materials)

Advanced

students

L1:

Japanese

L2: English

Petkova (2013) conducted a study on

documenting the effect and perceptions of this

curriculum in an intensive English program in

Southern California and also investigated the

perceptions of second language learners of English

about humor in their native language as compared to

perceptions about humor in English. By using mixed

methods combining a quasi-experimental pre-test

post-test design with qualitative data collection, the

results showed a T-test with a statistically significant

difference in students’ perceptions about humor in

English. Particularly, Hodson (2014) in Japan had a

study on humor competence for university EFL

students by using a combination of explicit teaching

of humor theories and knowledge schema, teacher-

and learner-led analysis of humorous texts, and

student presentations and suggested that humor

competence training during the course may have

aided participants’ appreciation of English humor.

Table 2: Studies on Humor Competence (continued).

Study

Research

goal(Humor

competence)

Design

Assessmen

t/

Procedure/

instrument

Erin

Baldwin

2007

Perception

T-test

Question-

naire/

Comprehe-

nsion

questions

Douglas

Wulf

2010

Appreciation

Socio-

cultural

knowledge

Classroom

-based

Zsuzsanna

Schnell

2010

Comprehens

ion

Classroom

-based

Visual

humorous

test

Melody

Geddert

2012

Recognition

Survey

Preliminar

y

investigati

on/

Questionna

ire

Maria

Petkova

2013

Perception

Quasi-

experimen

tal

Pretest,

post test

Richard J.

Hodson

2014

Appreciation

Experime

ntal

groups

Follow-up

joke

ratings

7 CONCLUSION

It can be said that humor competence can be

taught because it is the ability to recognize,

comprehend and appreciate humor. Actually, humor

is essential in the modern life and thus necessary in

the L2/EFL classroom. Humor competence is a

component of pragmatic competence and the fifth

component of communicative competence. Hence, it

is important to teach humor competence for better

communication. System of competence such as

linguistic competence, semantic competence, socio-

cultural competence and illocutionary competence

are needed for humor perception.

REFERENCE

Attardo, S., 2010. Linguistic Theories of Humor.

Walter de Gruyter.

Attardo, S., Raskin, V., 1991. Script Theory

Revis(it)ed: Joke Similarity and Joke

Representation Model. Humor Int. J. Humor

Res. 4, 293–347.

https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.1991.4.3-4.293

Bachman, L.F., 1990. Fundamental Considerations

in Language Testing. OUP Oxford.

Baron-Earle, F.L., 1995. Social media and language

learning: Enhancing intercultural

communicative competence.

Beermann, U., Ruch, W., 2009. How Virtuous Is

Humor? What We Can Learn from Current

Instruments. J. Posit. Psychol. 4, 528–539.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903262859

Can Humor Competence Be Taught?

395

Bell, N., 2007. How Native and Non-Native English

Speakers Adapt to Humor in Intercultural

Interaction. Humor-Int. J. Humor Res. - Humor

20, 27–48.

https://doi.org/10.1515/HUMOR.2007.002

Carrell, A., 1997. Joke Competence and Humor

Competence. Humor-Int. J. Humor Res. -

Humor 10, 173–186.

https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.1997.10.2.173

Chiaro, D., 2006. The Language of Jokes: Analyzing

Verbal Play. Routledge.

Deneire, M., 1995. Humor and Foreign Language

Teaching. Humor-Int. J. Humor Res. - HUMOR

8, 285–298.

https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.1995.8.3.285

Edwards, K.R., 1997. The Role of Humor as a

Character Strength in Positive Psychology 216.

Ermida, I., 2008. The Language of Comic

Narratives: Humor Construction in Short

Stories. Walter de Gruyter.

Fischer, 1889. Linguistic Aspects of Verbal Humor

in Stand-up Comedy 464.

Fraser, B., 1999. What Are Discourse Markers? J.

Pragmat. 31, 931–952.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)00101-5

Freud, S., 1974. Jokes and Their Relation to the

Unconscious. penguin, New York.

Grice, H.P., 1991. Logic and Conversation in

Pragmatics. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Hay, J., 2008. The Pragmatics of Humor Support.

Humor – Int. J. Humor Res. 14, 55–82.

https://doi.org/10.1515/humr.14.1.55

Hodson, R., 2014. Teaching Humour Competence

13.

Kasper, G., 1997. Can Pragmatic Competence Be

Taught?

Martin, R.A., 2007. Approaches to the Sense of

Humor: A Historical Review 47.

Matthews, J.K., Hancock, J.T., Dunham, P.J., 2006.

The Roles of Politeness and Humor in the

Asymmetry of Affect in Verbal Irony.

Discourse Process. Multidiscip. J. 41, 3–24.

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326950dp4101_2

Obrst, L., 2012. A Spectrum of Linguistic Humor:

Humor as Linguistic Design Space Construction

Based on Meta-Linguistic Constraints 3.

Petkova, 2013. Effects and Perceptions of A Humor

Competence Curriculum in An Intensive

English. Continuum, New York.

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Lewis, P. of S.P.J., Nicholls,

C.M., Ormston, R., 2013. Qualitative Research

Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students

and Researchers. SAGE.

Thomas, D.R., 1983. A General Inductive Approach

for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am.

J. Eval. 237–246.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

396