Utilizing Error Analysis in Teaching Practice: Is It Meaningful?

Odo Fadloeli and Fazri Nur Yusuf

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Jl. Dr. Setiabudhi no. 229, Bandung, Indonesia

Keywords: Error Analysis, Grammatical Errors, Pronunciation Errors, Vocabulary Errors, Code Switch, Subject Matter

Competence, Prospective Teachers

Abstract: Studies on error in language learning have been largely researched but utilizing error analysis in teacher

education remains a question. The present study aims at investigating the use of errors in prospective teacher’s

spoken language to enhance their subject matter competence. Involving 13 prospective English language

teachers of a public teacher education institution, the data were collected by teaching observation and

interviews and were analysed by content analysis under three barriers dimensions proposed by Yang and

Carless (2013). The findings indicate that all prospective teachers committed errors. The errors made are

among others grammatical, pronunciation, and vocabulary errors, and code switch. The errors made can be

categorized as errors and mistakes. Those errors are due to their limited knowledge and lack of practice. The

prospective teachers can immediately correct their errors when feedback is provided by their supervisors. The

findings suggest that it is necessary for teacher education institutions to provide and train their prospective

teachers fundamental trainings and practice on subject matter. These trainings and practices may reduce the

prospective teachers’ anxiety and in implementing their mastery of subject matter. There is highly

recommended to provide sufficient feedback provision that serve dialogicity, meaningfulness, and timeliness

and insights.

1 INTRODUCTION

Studies on error analysis in language learning

have been largely researched but utilizing error

analysis in teacher education remains a question. In

the meantime error analysis is “a ‘device’ the students

use in order to learn” (Khansir, 2013). Besides, the

prospective teacher can make use of their errors made

to help themselves to connect their prior knowledge

and the new material or skills presented (Abushihab,

2014).

Research on error analysis has shown their

contribution to the enhancement of subject matter

competence. First, a study to 30 ESL students in UAE

shows that error analysis influences them to boost

their second language acquisition (Alahmadi, 2014).

Second, a study to five transcripts of Indonesian high

school students’ speaking performance have

indicated that they fail to fill in the gaps of their

grammatical errors (Rini, 2014). Third, a study to

Chinese high school students shows error analysis

helps them identify their errors, when, and how to

cope with the errors (Xie and Jiang, 2007). Fourth, a

study to ESL students in Bangladesh indicates that

error analysis helps students to make balance when to

give corrective feedback and when not when students

perform their speaking (Kayum, 2015). Fifth, a study

on error analysis supports scaffolding to make

students learn more effectively to succeed compared

to giving direct feedback (Maolida, 2013). Sixth, a

study on error analysis helps students to identify the

effect of students’ native language and their second

language acquisition (Habibullah, 2010; Mustafa et

al., 2017).

Those studies serve a strong argument that error

analysis on subject matter delivered through

feedback—defined as inputs on one’s progress

towards their improvement (Lewis, 2002) promote

betterment. This argument encourages prospective

teachers to make a reflection on their own mastery

and performance. Furthermore, it promotes better and

more systematic feedback provision in teacher

education institutions in particular. Based on those

arguments, it is necessary to conduct a research on

error analysis that supports feedback provision to

Fadloeli, O. and Yusuf, F.

Utilizing Error Analysis in Teaching Practice: Is It Meaningful?.

DOI: 10.5220/0008216400002284

In Proceedings of the 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference (BELTIC 2018) - Developing ELT in the 21st Century, pages 243-249

ISBN: 978-989-758-416-9

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

243

enhance English prospective teachers’ subject matter

competence.

To be a competent professional teacher is a

desirable and high demand for every teacher,

including an English teacher. Language teaching

experts assert that professional teachers must have the

following competencies: professions/fields of study,

pedagogy, social, and personal.

To obtain the competencies mentioned, training

for teachers is required. Teaching practicum and

teaching practice as part of teacher education is

considered not strong enough to help prospective

English teachers to become professional and

competent in their field of expertise.

In this research, error analysis is used as a tool to

improve the competence of field of study of English

teacher candidate. Amid the diversity of

understanding of mistake and errors, this study uses

the definition of error as "the mistakes which cannot

be corrected by students themselves (Harmer, 2008)

that occurs as the result of the unknown language

rules. the reflection of gaps in the students' knowledge

"(Ellis, 1997, p 17). When viewed from the final state

of the error, it is shown that the student's ignorance of

the rules of the language he is aware of or not (Yang

& Xu, 2001, p.17) thus requires others to correct him.

The role of error analysis on the provision of

feedback on competencies in the subject matter

competence of the teacher candidate is no doubt. The

results of error analysis provide information related to

the dimensions of feedback (content, social-affection,

and structure) that can be a source of barriers to the

acquisition and improvement of competencies when

not well exploited by the candidates of English

teachers resulting in a lack of student understanding

of the material being taught. This condition

encourages the present study to utilize and promote

the use of error analysis within a dialogic feedback

process (Stern and Backhouse, 2011; Sutton, 2009).

The competence of subject matter in teaching is not

only a matter of transmitting knowledge, but must

have a capacity-building orientation of learners "to

engage in dialogue." In these dialogues, knowledge is

constantly being built, deconstructed and

reconstructed" (Wegerif, 2006).

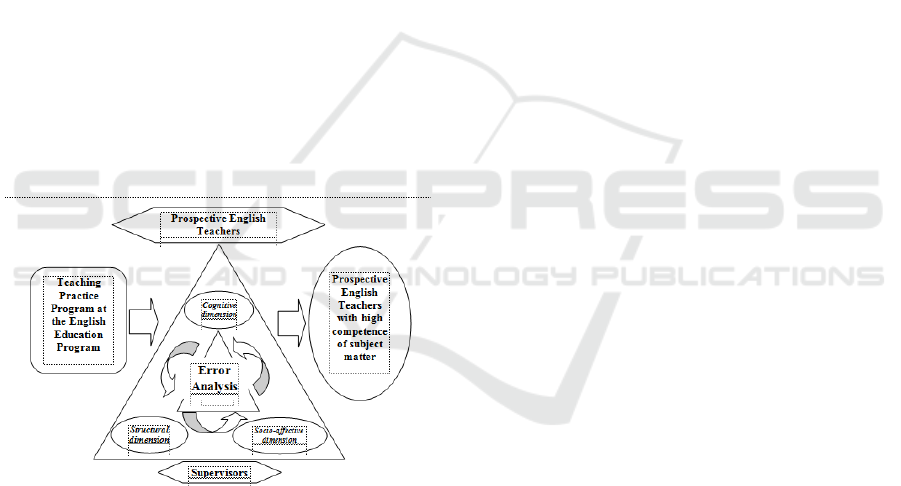

To examine how error analysis in supporting the

feedback process as part of improving the

competence of the field of English teacher candidates

can be seen in Figure 2. The three dimensions of Yang

and Carless (2013) will be the basis and source of

error- in this study. These three dimensions can be

illustrated in the following figure.

The three dimensions as the source of error analysis

become important information in the feedback

process. The first dimension is the cognitive

dimension associated with the content that indicates

the quality of the work of the learner. The content of

feedback in this context is not limited to academic

knowledge. This dimension can include the nature of

the task and the learning needs of the learners. This

dimension will encourage learners' involvement to

learn independently, the ability to independently

monitor their learning. Some of the following focus

are examples of this dimension, including: discussion

of concepts, techniques, task completion strategies,

procedures, skills, values, attitudes, beliefs, and

principles (Yang and Carless, 2013).

The second dimension is the socio-affective

dimension related to negotiation between feedback.

Yang and Carless (2013) define it as "social practice"

in which relationship management is the emotional

centre affecting the way of learning. They emphasize

the concern of the inner dimension of how social role

responses in their learning environment and how the

emotions of learners are involved to carry out

learning and do learning tasks. Yang and Carless

(2013) state that effective learners use feedback to

channel their emotions toward self-learning. Such

self-learning ability can support strategies to motivate

and assure emotions as part of natural learning.

The third dimension is the structure dimension

consisting of organization and feedback management.

Yang and Carless (2013) add this component must

work with resources to generate and provide

feedback. They advise teachers and institutions to be

part of the two feedback processes.

There are four ways error suppression is given in

helping learners learn to do well. First, error analysis

helps learners to verify that they are capable of

reaching their learning target. Second, error analysis

allows them to assess their strengths and weaknesses.

Third, error analysis can encourage learners to grow

in line with the process. Finally, error analysis can

help them recognize and share insights about the

world (London and Sessa, 2006).

Associated with the competencies required as a

professional teacher, error analysis becomes a

provider of feedback information empirically

assisting prospective teachers. Error analysis can

identify gaps between existing abilities and desired

capabilities (Price et al., 2011). In addition, error

analysis can clarify misunderstandings and can

identify weaknesses of learning strategies and skills

(Sadler, 2010). It can also contribute to independent

learning (Pekrun et al., 2002) and can nurture the

potential and ability of aspiring teachers to be

independent, solve problems, self-evaluate, and

reflect (Sadler, 2010).

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

244

To be competent is the main goal of every

teacher. This is certainly true for English teachers.

Various characteristics of being a competent teacher

are required for prospective English teachers who are

expressed from experts and educational institutions as

well. One suggested by The National Academy of

Education (Darling-Hammond et al., 2005). It is

proposed that the teacher be competent when he has

the following knowledge. First, teachers have

learners' knowledge and their development. Second,

teachers have knowledge of the subject matter and

curriculum objectives. Third, teachers have

knowledge of teaching. This competency requires the

teacher to have knowledge of the content, learning

process, and learning process of the learner related to

the content. Finally, he is able to assess student

learning outcomes and be able to manage the class.

The present study focuses on the competence of

teaching English teacher candidates. Their teaching

competencies are demonstrated over three months of

Teaching Practice Program supervised by lecturers

from the university and teachers from the target

schools. Improved teaching competence is considered

one of the most frequently used competency demands

as an analytical variable to explain why some teachers

are more effective than others (Hendriks et al., 2010).

Figure 1: Error Analysis in Teaching Practice towards

Subject Matter Competence

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Prospective English teachers and their

supervisors were involved as respondents. The

prospective English teacher is the fourth year college

students of a public university in Bandung, Indonesia.

They were enrolled as students of the Teaching

Practice Program (known as PPL) at high schools as

a requirement. The supervisors are lecturers from the

university and the cooperating teachers of the target

schools assigned by their institutions as mentors.

Both of them were on duty to provide English teacher

candidate support during the Teaching Practice

Program. Prospective English teachers and their

supervisors were engaged in communication and

open sharing of understanding during the feedback

process.

Data collection was done by using observation

instruments and recorded interviews. From the

observation instrument, data related errors were

collected in the oral prospective teachers through

presentation and/or teaching simulations. From the

interviews, collected data that validate data from

previous instruments and complete it with data causes

of the error. In-depth interviews with prospective

English teachers were recorded periodically after they

teach; their teaching performance is a result of a

revision of their previous teaching performance based

on the feedback given by the supervisors. The data

collected were categorized into a feedback dimension

trilogy.

After collecting the data, they were converted

into dimensions trilogy: cognition dimension; what

cognitive dimension, the social-affection dimension;

how prospective teachers interact and respond to

errors made (socio-affective dimension), and

organizational and management dimensions; in what

way the error is managed (structural dimension).

Furthermore, the collected data is analyzed using

content analysis with the framework: content,

organization, grammatical aspects, and

pronunciation.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

From the data collection conducted either

through observation or interviews, there was found

four categories of mistakes made by prospective

teachers whether consciously or subconciously.

Cognitively, the error is divided into: grammatical

errors, pronunciation errors, errors in vocabulary use,

and code switches.

Grammatical errors dominate the mistakes made

by the prospective teachers. There are 51 errors

consisting of the use of the word article, the use of

WH Question, the use of subject-verb agreement, the

use of plural-singular, the use of prepositional verbs,

the use of prepositional phrases, the use of many-

much, the use of gerund, the use of tense, the use of

command sentence (imperative), use of introductory

"there". Here are some examples of grammatical

errors made by prospective teachers as displayed in

Table 3.1.

Utilizing Error Analysis in Teaching Practice: Is It Meaningful?

245

The pronunciation errors were made 22 times. In

general, they were made at word level. The errors

made is presented in the following Table 3.2.

From the example in Table 3.2, there appears to

be a number of pronunciation that are not in

Indonesian pronunciation, such as the sound of the

word focus, the /ɵ/ in word mouth, and the /ʧ/ in

pouch . In addition, there is a difference in English

pronunciation between what is read and what is

written that causes errors of pronunciation to occur.

Furthermore, the vocabulary error is done six

times. The error lies in the use of some English words

that do not fit the context. The following errors are

presented in the vocabulary. The details are presented

in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 shows to be an indirect effect of

Indonesian on the misuse of vocabulary use,

especially on presentate as the translation of present,

matery – material , and raise up – raise hands.

Finally, the next mistake made by the

prospective teacher lies in the transfer of code from

the Indonesian language into English. Found 14

mistakes made by the prospective English teachers.

The errors are presented in the following Table 3.4.

From Table 3.4 regarding errors of code switch,

they appear that there are errors in translating

Indonesian speech or using English utterances that are

commonly used by the English native speakers.

From the above findings, the prospective

English teachers generally made errors based on two

reasons. First, permanent errors are due to ignorance

and second due to temporary error. A temporary error

can just be identified when the prospective teachers

are asked to revisit the mistakes made and they are

able to correct the mistake after being assisted by their

mentors. This is clearly in line with statements, both

from Harmer (2007) and from Ellis (1997). They both

argue that the cause of their mistakes can stem from

their ignorance of the rules (in this case related rules

in English) or by mistake that is not intentional.

Permanent errors are mostly done in categories

of grammatical errors, vocabulary errors, and

language overrides. The errors in pronunciation tends

to be temporary. This happens because nervousness

when observed by supervisors and when expressing

certain words in rush. This finding shows similar

findings of Yang and Xu (2001) stating that they

made a mistake in the language because of ignorance

consciously or subconsciouly. Therefore they need

others to identify and correct them.

Grammatical errors and misconduct are possible

because the prospective teachers are less or less likely

to use English in their day-to-day language use,

especially in the classroom or their negligence in

using acceptable English Rini (2014). The habit of

using the Indonesian language or the mother tongue

of the students strongly does not support the

preservation of English mastery that should be used

in the classroom. This can also lead to many details

related to aspects of grammatical rules and

pronunciation in English cannot be functioned

properly.

Table 1: Grammatical Errors

Types of

Errors

Descriptions

The Correct

Grammar

Use of article

What kind of the

text?

Unnecessary

use of article

What kind of

text is it?

Use of W-H Question

Who is the

announcement

for?

Misuse of WH

Question

Whom is the

announcement

for?

Use of subject-verb agreement

This is consist

of...

I have been fill

for you.

Subject-verb

disagreement

This consists

of...

One has been

filled out for

you.

Use of plural-singular

Five sentence

No suffix “s”

Five sentences

Use of prepositional verb

...according

with...

...related with...

Inappropriate

phrasal verbs

...according

to…

...related to...

Use of prepositional phrase

This part body

of...

Inappropriate

prepositional

phrase

This part of

body...

Use of pronouns

For our today.

What is

someone doing?

Inappropriate

pronouns

For us today.

What is he/she

doing?

Use of many-much

Collect this stick

as much as you

can.

Misuse of

“much” for

countable nouns

Collect this stick

as many as you

can.

Use of gerund

After watch

video...

Before

continue...

Inappropriate

use of “gerund”

After watching

video...

Before

continuing...

Use of tense

She introduce

you to me via

email.

Misuse of

”tense”

She introduces

you to me via

email.

Use of imperative

Telling to your

friend.

Inappropriate

imperatives

Tell it to your

friend.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

246

You ask your

group...

Ask your

group...

Use of introductory “there”

There are two

classification

about...

Inappropriate

use of

“introductory

‘there’”

There are two

classifications

of...

Table 2: Pronunciation Errors

Types of

Errors

Descriptions

The Correct

Pronunciation

Focus

Pronounced

/fɔkjus/

/fɔkɘz/

Mouth

Pronounced

/mɔt/

/mauɵ/

Rough

Pronounced

/rɔg/

/rɅf/

Height

Pronounced

/heit/

/hait/

Purpose

Pronounced

/purpɔs/

/pɜ:pɘs/

Effort

Pronounced

/efɔ:t/

/efɘ:t/

Pouch

Pronounced

/pɔʧ/

/pauʧ/

Tabel 3: Use of Vocabulary Errors

Types of Errors

The Correct

Vocabularies

Presentate

Present

Matery

Material

Whether you still remind

of that?

Whether you still

remember of that?

I want you to change with

your friend.

I want you to swap/swop

with your friend.

Train station

Railway station

Raise up.

Raise your hand.

Tabel 4: Errors in Code Switch

Types of Errors

The Correct

Words/Utterances

What is storage?

What is the Indonesian for

“storage”?

Who wants to answer?

Can anyone answer the

question?

I want to make groups

consist of...

I’d like you to work in

groups of...

Okay, can.

Yes, it can be the answer.

Any else?

Anything else?

Attention here.

Attention please.,ncx

Make me sure.

Make sure.

Errors in the vocabulary category can be caused

by several factors. First, it is related to the vocabulary

mastery of the intended teachers in their learning.

When the mastery of vocabulary is a little, it allows

the limitations in utilizing the owned vocabulary. The

higher the level of vocabulary mastery of the

prospective teachers is, the higher the likelihood of

using the variety of vocabularies they have

(Abushihab, 2014; Khansir, 2013) in tiered and

continuous (Maolida, 2013).

Second factor is the prospective teachers’ efforts

in using the new vocabulary. If there is any doubt

about using a new vocabulary, then there is a great

possibility that no vocabulary will increase or be

dominated by prospective teachers (Alahmadi, 2014).

Third factor is the efforts of prospective teachers to

use the vocabulary that they already have. The more

vocabulary is commonly in use, the more likely it is

that the vocabulary is often used and the more controll

in various contexts of use (Kayum, 2015; Khansir,

2013).

Because of the mistakes made above due to basic

knowledge problems, these permanent errors can be

categorized into cognitive constraints (Yang and

Carless, 2013). Yang and Carless suggest that to

overcome such errors it is necessary to provide

suggestions. This suggestion is presented in the

feedback given by the mentor in particular, both from

the coperating teachers and the university teachers. In

addressing these errors, the dialogic feedback process

will greatly enhance knowledge as well as exploiting

and exploring the knowledge that these aspiring

teachers have (Xue-mei, 2007; Maolida, 2013). This

is in line with London and Sessa (2006) and Price, et

al. (2011) who state when prospective teachers can

identify their shortcomings and potentials through

error analysis, they are recognizing their world,

recognizing their profession as teachers. The

prospective teachers will be able to choose their

learning strategies as independent learners (Pekrun, et

al., 2002), independent, be able to solve problems, be

capable of evaluating, and be able to reflect (Sadler,

2010).

Mistakes over code switch may be due to the

influence of the mother tongue on the process of

mastering English and/or the influence of learning

English on the acquisition of English. Through error

analysis, it is expected that how the process of

learning English continues even though the

prospective teachers will devote themselves as a

professional. This is in line with the findings of

Habibullah (2010) and Mustafa et al., (2017) who

found that error analysis can help acquire the English

language as of that the prospective teachers are doing.

Feedback delivery from both mentors and peers

allows prospective teachers to develop themselves

Utilizing Error Analysis in Teaching Practice: Is It Meaningful?

247

better over time. Through the feedback they receive

will provide great opportunities to find their

potentials to improve their subject matter competence

and the potential to further develop themselves

through the feedforward process (Xue-mei, 2007;

Maolida, 2013).

This study clearly shows that prospective

teachers who are the subject of this study show their

deficiencies in four categories. Through the error

analysis of the four categories described above,

prospective teachers will be able to identify their

faults independently (Xie and Jiang, 2007) and be

able to improve on their own competence (Kayum,

2015) as well as a solution to the problems they face

in the future day.

4 CONCLUSION

Based on the findings and discussion of this study, the

following conclusions can be drawn. Firstly, not all

mistakes made by the prospective teacher is a

permanent mistake. Most of these are temporary

errors. They realize that they know they are wrong.

Giving prospective teachers a chance to identify all

errors including their strengths becomes crucial in

identifying and making use of the mistakes made in

order to become a lesson for not making similar

mistakes. Secondly, mistakes made by prospective

teachers must be acknowledged to always exist and is

a potential that can be used as input for mentors as

well as learning materials that can be utilized by

prospective teachers to improve the quality of

mastery of their field of study. Thirdly, systematic

efforts through feedback both from mentors and

colleagues enable prospective teachers to identify

existing weaknesses and then design programs to

address them through the utilization of their

respective potential.

Related to the findings and discussion, the

following suggestions are in need to be done. Firstly

to prospective teachers, it is necessary to improve the

practice of using English as the language of

instruction in the classroom. Secondly to mentors,

cooperating teachers, university teachers, or similar

related professions can take error analysis as a study

to enrich their learning and teaching process. Thirdly

to the school or related institution managing the

education, it may lead teachers, lecturers, instructors,

or related professions to improve their competence,

especially in the field of study. They are expected to

have the ability to detect errors, find causes of errors

made, and design follow-ups or feedforward in the

form of programs that can help prospective teachers

to find solutions to overcome the problems

experienced.

REFERENCES

Abushihab, I., 2014. An Analysis of Grammatical Errors in

Writing Made by Turkish Learners of English as a

Foreign Language. Int. J. Linguist. 6, 213–223.

https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v6i4.6190

Alahmadi, N.S., 2014. Errors Analysis: A Case Study of

Saudi Learner’s English Grammatical Speaking Errors.

Arab World Engl. J. 15.

Darling-Hammond, L., Baratz-Snowden, J., Education,

N.A. of E.C. on T., 2005. A Good Teacher in Every

Classroom: Preparing the Highly Qualified Teachers

Our Children Deserve, A Good Teacher in Every

Classroom: Preparing the Highly Qualified Teachers

Our Children Deserve. Wiley.

Ellis, R., 1997. SLA Research and Language Teaching.

Habibullah, M.M.K., 2010. An Error Analysis on

Grammatical Structures of The Students’ Theses.

Harmer, J., 2007. How to Teach English (Second Edition).

ELT J. 62, 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn029

Hendriks, M.A., Luyten, H., Scheerens, J., Sleegers, P.,

Steen, R., 2010. Teachers’ professional development:

Europe in international comparison. Office for Official

Publications of the European Union.

https://doi.org/10.2766/63494

Kayum, M.A., 2015. Error analysis and correction in oral

communication in the efl context of Bangladesh. Int. J.

Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 5.

Khansir, A.A., 2013. Applied Linguistics and English

Language Teaching 7.

Lewis, M., 2002. Giving feedback in language classes.

SEAMEO Regional Language Centre, Singapore.

London, M., Sessa, V., 2006. Group Feedback for

Continuous Learning. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 5, 303–

329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484306290226

Maolida, E. H., 2013. Oral Corrective Feedback and

Learner Uptake in a Young Learner EFL Classroom: A

Case Study in an English Course in Bandung. A Thesis,

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia.

Mustafa, F., Kirana, M., Bahri Ys, S., 2017. Errors in EFL

writing by junior high students in Indonesia. Int. J. Res.

Stud. Lang. Learn. 6, 38–52.

https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2016.1366

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., Perry, R. P., 2002. Positive

Emotions in Education. Retrieved from

https://kops.uni-

konstanz.de/bitstream/handle/123456789/13908/Pekru

n_positive_emotions.pdf?sequence=2.

Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., 2011. Feedback: focusing

attention on engagement. Stud. High. Educ. 36, 879–

896. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.483513

Rini, S., 2014. The Error Analysis on the Students of

English Department Speaking Scripts. Regist. J. Lang.

Teach. IAIN Salatiga 7.

Sadler, D.R., 2010. Beyond feedback: developing student

capability in complex appraisal. Assess. Eval. High.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

248

Educ. 35, 535–550.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903541015

Stern, J., Backhouse, A., 2011. Dialogic feedback for

children and teachers: evaluating the ‘spirit of

assessment.’ Int. J. Child. Spiritual. 16, 331–346.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1364436X.2011.642853

Sutton, P., 2009. Critical and Reflective Practice in

Education Volume 1 Issue 1 2009 1, 10.

Wegerif, R., 2006. Dialogic Education: What is it and why

do we need it? Educ. Rev. 19, 58–67.

Xie, F., Jiang, X., 2007. Error Analysis and the EFL

Classroom Teaching.

Yang, M., Carless, D., 2013. The feedback triangle and the

enhancement of dialogic feedback processes. Teach.

High. Educ. 18, 285–297.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.719154

Yang, X., Xu, H., 2001. Errors of Creativity: An Analysis

of Lexical Errors Committed by CHinese ESL Students.

Lanham: University Press of America, Inc.

Utilizing Error Analysis in Teaching Practice: Is It Meaningful?

249