Process Type of Angkola Language Transitivity

Husniah Ramadhani Pulungan

1

, Riyadi Santosa

1

, Djatmika

1

, Tri Wiratno

1

1

Universitas Sebelas Maret, Jl. Ir. Sutami No. 36A Surakarta 57126, Indonesia

Keywords: process, type, transitivity, angkola, language

Abstract: Angkola language is one of the Batak language subgroups in South Tapanuli, North Sumatera, in Indonesia.

This article aims to know the process type of Angkola language transitivity. It is a part of experiential meaning

in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL). The objectives are to find out the forms and the idiosyncratic in it.

The research methodology uses Spradely method based on spoken data that is Parhuta-huta Film because this

film can present language in society daily life. The finding shows that the Angkola language has six process

types, namely: material process, mental process, verbal process, behavioral process, relational process, and

existential process. Besides, the idiosyncratic found some unique formation clauses called in Angkola

language clause. Moreover, there are some different process positioning types in each Angkola language.

Some of the process is located at the beginning of the clause and that looks like a cultural habit in the

society.The different process positioning shows that the Angkola people have a direct conversation culture

therefore the research like this must be explored more to complete the literature in similar study.

1 INTRODUCTION

Angkola is one of Batak subgroups in South

Tapanuli Regency, North Sumatera Province,

Indonesia as Batak language is divided into six

types, namely: Angkola, Karo, Mandailing, Pakpak,

Simalungun, and Toba (Hasibuan 1972) Angkola is

one of the languages of the Southern Tapanuli

region, which is used daily by the people of

Marancar, Angkola, Sipirok,

Padangbolak/Padanglawas, Barumun-Sosa, and can

be understood by residents of Mandailing Natal

district only since it has different or accent compare

to other types (Tinggibarani 2008). Thus, Angkola

language is a language that still has active speakers

and studying its linguistics system is crucial to

preserve and document the language as it is one of

the cultural heritages of the archipelago, Indonesia.

1.1 History of Angkola

Based on history, Angkola Tribe is a tribe of

Indonesia who inhabit Angkola region in South

Tapanuli regency, North Sumatra Province. The

name Angkola comes from the name of the river in

Angkola, which is the river (stem) of Angkola.

According to the story, the river named by Rajendra

Kola (Chola) I, ruler of the Chola Kingdom (1014-

1044M) in South India when it entered through

Padang Lawas. The area to the south of Batang

Angkola called Angkola Jae (downstream) and the

north named Angkola Julu (upstream). Then the

people of the Chola kingdom left Angkola at the

time of the epidemic. Oppu Jolak Maribu with

Dalimunthe clan is the next Angkola figure that

emerged after the reign of Rajendra Chola I. Then

for the first time he founded huta (village)

Sitamiang. Next, Pargarutan means to sharpen the

sword. Tanggal is where to take off the day/place

calendar batak, and others. Then enter the other

tribes from all directions to the region of Angkola.

The clans that inhabit Angkola in general are

Dalimunthe, Harahap, Siregar, Ritonga, Daulay,

and others. Angkola gained Islamic influence from

Tuanku Lelo who spread Islam in the Padri mission

(1821) from Minangkabau (Lubis 2011).

Pulungan, H., Santosa, R., , D. and Wiratno, T.

Process Type of Angkola Language Transitivity.

DOI: 10.5220/0008215300002284

In Proceedings of the 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference (BELTIC 2018) - Developing ELT in the 21st Century, pages 21-30

ISBN: 978-989-758-416-9

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

21

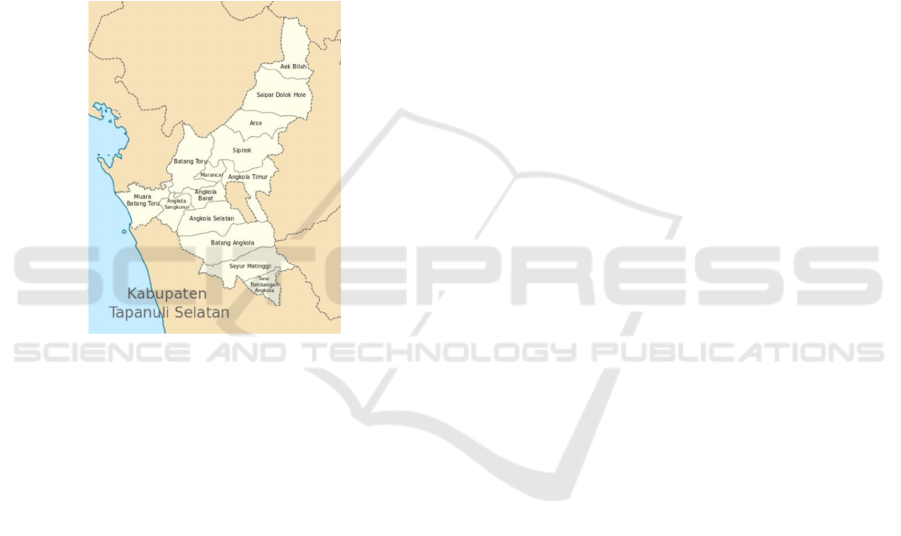

1.2 Location of Angkola

Angkola region is located in South Tapanuli

District. This district was originally a very large

district and capitalized in Padangsidimpuan. The

areas that have been split from South Tapanuli

Regency are Mandailing Natal, Padangsidimpuan

City, Padang Lawas Utara, and Padang Lawas

Selatan. After the expansion, the district's capital

moved to Sipirok (Affairs 2015). However, in this

case, Padangsidimpuan will remain included in the

Angkola region that still uses Angkola language and

was formerly the Capital of South Tapanuli District.

The map of Angkola as follows.

Figure 1: Map of South Tapanuli District (Angkola

Region)

South Tapanuli Regency has boundaries

consisting of: regency of Tapanuli Utara and

regency of Tapanuli Tengah in the north. Regency

of

Mandailing

Natal in the south. West by the Indian

Ocean. The east is bordered by Riau Province and

Labuhan Batu Regency. Then, the city of

Padangsidimpuan where is entirely surrounded by

this district. The total area 6.030,47 km2, total

population 299.911 people in Permendagri No.39

Tahun 2015 (Affairs 2015).

1.3 Types of Angkola Language

Angkola language usage is adapted to the situation

and the time. Based on this statement, Angkola is in

nine types as follows: (1) Language Hasomalon is a

language used in everyday life. (2) Adat Language

is the language used in traditional ceremonies. (3)

Andung language is the language used when crying.

(4)

Bura/Jampolak

is the language used when angry.

(5) Language Perkapur is the language used when

in the jungle. (6) Language Turi-turian is a language

used when marturi or tell a legend. (7) Language

Aling-alingan is a language used to convey

something implied by using words of comparison or

words that tell something so that those who hear the

word immediately understand the purpose/purpose

of the words delivered. Users of this language are

young adolescents or adat figures. (8) Language

Kulum-kuluman

is a language that uses objects such

as betel or other objects that hands over to a person

or a crowd and those who receive the object can

understand what the intention is to convey. (9)

Marhata Balik is a language commonly used by

young teenagers by flipping through the usual words

and then pronounced it. This language requires

dexterity to analyze what it wants to convey so it

can answer directly in the same way (Tinggibarani

2008).

Thus, when viewed in terms of literature,

Angkola is a language that has a high culture. The

statements can be from the application of these

types of Angkola language in the life of people of

South Tapanuli Regency every day. Unfortunately,

the Angkola language has limited written language

documentation because it only passed down orally

from generation to generation.

1.4 Livehood of Angkola Society

Angkola society is the people who still practice

Angkola culture in everyday life and use the

language of Angkola as his mother tongue.

Generally, Angkola society is farmers and planters.

The famous produce agricultural is coffee, rice,

salak, rubber, cocoa, coconut, cinnamon, pecan,

chilli, onion, leek, and vegetables (Hasibuan 1972).

Nevertheless, Angkola people have a high

spirit in sending their children to get a better life.

Therefore, Angkola society also has been familiar

with the culture of wander. His generation is

motivated to wander both to gain knowledge and for

a career aimed at generating life experiences that

can mature his soul and mind. Moreover, its

generation is not narrow minded, humble, and

appreciate each other's advantages. As a result,

when the generations return to their hometown, they

will do martabe (marsipature huta na be) in the

other words, building their own village or re-build

the village.

1.5 Angkola Topography

Residents of Angkola live in all parts of South

Tapanuli Regency. The topography of the region is

valleys and hills that are still rich in natural

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

22

resources. Similarly, rare flora and fauna can still be

found. The beautiful natural panorama and the cool

air become one of the attractions of this region.

Communities of the Angkola tribe generally live

from agriculture and plantation sectors namely

production of rice, vegetables, salak, coffee, cocoa,

rubber, coconut, and cinnamon. Other activities are

raising livestock such as chickens, ducks, geese and

buffaloes or cows (Hutahaean 2013).

1.6 Social System of Angkola Society

Sociologically, the social structure of Batak society

consists of three groups called Dalihan na Tolu

'three stoves'. The three furnace poles considered to

be fairly steady and strong, to lay a pot or other

cooking utensils on it. That is, according to

Ompunta Narobian (the ancestors) to build the life

it needs three groups to support each other such:

kahanggi, anakboru, and mora. Kahanggi is one of a

group of descendants or a family. If there is a

different clan, this is because pareban and pamere

put into called the group kahanggi pareban.

Anakboru is another group of clans who take our

daughters, and so on. It is also called anakboru are

all families of parties who take boru from our side.

Mora is another group of clans that given to our

party sekahanggi, or the brother of parumaen (son-

in-law), wife and mother. Obviously, the mora is the

one who gives the boru to our side (Managor 1995).

1.7 The Development of Angkola

Language

The development of Angkola language is

indeed overlapping with the Mandailing language.

Some say that Angkola-Mandailing is one

language and others say it separated Angkola and

Mandailing language itself. There is also a name in

the language of Batak Angkola. Which is the

correct language name? This does not happen to

escape from the state of the development of its

territory. Initially, the area of Angkola and

Mandailing united is in the South Tapanuli district,

so the mention of the local language often called

Angkola-Mandailing. Although in fact, some

vocabulary, dialect and accent have differences.

Then, the issuance of the Law of the Republic of

Indonesia Number 12 of 1998 passed on 23

November 1998 on the establishment of

Mandailing Natal Regency in South Tapanuli

Regency. The area divides into two districts,

namely Mandailing Natal District (Panyabungan

Capital) with the administrative area of eight

districts and regencies of Tapanuli Selatan (the

capital of Padangsidimpuan) with the

administrative number of sixteen sub-districts. Up

to 2011, South Tapanuli Regency has been

expanded into one city (Padangsidimpuan) and

three districts (Mandailing Natal, and most recently

with Law No. 37/2007 and Law 38/3007 on

Formation of Padang Lawas Utara and Padang

Lawas Regency) (District Goverment of Tapanuli

Selatan 2011).

However, the language of Angkola also relates

to Toba language (Mualita 2015). Thus, this time

the researcher will take a stand on the usage of the

name of the language used. Researchers chose to

use the term Angkola because in 1995 the Center for

Development and Language Development of the

Ministry of Education and Culture Jakarta has

issued the Indonesia-Angkola Dictionary (Lubis,

Syahron 1995). Based on this, the researcher will

refer to the name of Angkola language as it done by

the Center for Development and Language

Development.

In general, the review of previous Linguistic

Systemic Functional (SFL) research is still

concerned with transitivity analysis. It describes

certain texts or specific discourses of genres and the

registers (Santosa 2003); (Putu Sutama, I Gusti

Made Sutjaja, Aron Meko Mbete n.d.); (Muhartoyo

2012); (T. Ledua Alifereti 2013); (Hermawan,

Zenereshynta & Ardhernas 2014); (Budiasa 2007);

(Bello 2014); (Lima-lopes 2004); (Koussouhon

2015); (Behnam & Zamanian 2015); (Khristianto

2015); (Chen 2016); (Basori & Wiranegara 2016);

(Valipour, Aidinlu & Asl 2017); (Muksin 2016);

(Kavalir 2016); (Maulina 2015); and (Evangeline &

Fomukong 2017). However, in previous studies the

transitivity of meaning holistically has not been

addressed and a complete of experimental process

does not get much attention since the focus of

conducted analysis merely certain texts or

discourses. Furthermore, the previous studies focus

on material processes, mental processes, verbal

processes, behavioral processes, relational

processes, and existential processes, whereas an

analysis related to one circle consisting of fifteen

species specifically not disclosed.

Specifically, the semiotic and LSF research

related to Angkola itself is still in the same state as

the previous explanation. Research on Angkola

language is also still focus on one of custom text

only (Rosmawaty 2011); (Ikawati 2014); (Lubis

2015); and (Lubis 2017). The results of these

studies reveal the interpersonal meaning, meaning

the context of the situation, cultural context,

function, and values of local wisdom but

discussion on transitivity in Angkola particularly

is rarely found. If there is transitivity related to

Angkola it is a transitivity variation of the

translational text of Mangupa from Mandailing to

Process Type of Angkola Language Transitivity

23

English (Nasution 2009). However, there is no

research about exposure of transitivity investigated

in a holistic way.

Meanwhile, if the Angkola language predication

was analyzed by using the Linguistic Systemic

Functional Approach, transitivity is not just a

predication but it is a complete transitivity analysis

obtained. Since the clause as the

embodiment of experience (ideational meaning:

experiential) is essentially composed of three

constituents, namely: (1) process or event, (2)

participants, and (3) circumstantial. Then, the three

constituents have the realization and form of a

certain group of words, such as the process and

events realized into the predator in the grammatical

function and in the form of a verb group.

Meanwhile, the participants realized are in the form

of the subject and the complement in the form of a

noun. Furthermore, circumstance realized in the

form of adjunct in the form of noun or preposition

and adverb phrases. So that, there are six

experimental processes in Indonesian language,

namely: material, mental, verbal, behavioral,

relational, and existential. The circumference

consists of eight types: angle, extent, location,

manner, cause, accompaniment, problem, and role

(Santosa 2003). Next, this theory will apply to

Angkola language to exposure how the process type

in it.

This statement is similar to Halliday (Halliday &

Matthiessen 2014) states the system of transitivity

provides the lexicogrammatical resources for

construing a quantum of change in the flow of

theories as a figure - as a configuration of the

elements of a process. Process construed into a

manageable set of process types.

In addition, Thompson claims that the term

transitivity will probably be familiar as a way of

distinguishing between verbs according to wether

they have an Object or not (Thompson 2013). In

addition, studies that emphasize on metafungsional

which includes analysis of transitivity in it (Alice

Caffarel 2004) and her friends have been done in

French, German, Japanese, Tagalog, China,

Vietnam, Telugu, and Pitjantjatjara. All of these

languages discussed in the language typology

viewed in a perspective functionand Angkola

language is excluded. Then, the SFL application on

the Indonesian clause (Sujatna 2012) still analyzes

the clause as a message and clause as a

representation. This research can be a reference also

for Angkola language research.

Based on the above review, researchers still

have room to analyze transitivity in terms of the

experimental process in Angkola since previous

researchers are still researching transitivity in other

languages so that the Angkola language still has a

chance to analyze further. Even if there is already

research, still at the stage of identifying and

classifying it, the results of his research has not

reached the stage of finding patterns of cultural

themes and interpretations. Thus, the research gap

this time is the spoken data. The people practice the

language in daily communication. Therefore, this

study aims to find the type of process in the

transitivity of Angkola language and the

idiosyncratic symptoms in spoken one.

This research uses descriptive qualitative

method. The design used is ethnography model

from (Spradely 1980). Then, data source was taken

from spoken data (in this case dialogue in film with

the title Parhuta-huta as this film represents the

daily spoken language of Angkola society.

Figure 2: Parhuta-huta’s Film

The data are utterances that contain Angkola

language transitivity from the actors and actress in

Parhuta-huta’s Film. The data collection is from

observation technique followed by observation and

field note then it is analyzed under SFL perspective.

2 PROCESS TYPE

Process type contains experience. Experiences

consist of a flow of events or goings-on.

Realizations of each process type contained in

different models or schemes then in interpreting the

domain of a particular experience as a figure of a

certain kind - a model as illustrated above to

interpret meaning: Token (usually) + Process

(means) + Value (mostly); and for the purpose of

wanting to shower: [Senser:] I + [Process:] do not

want + [Phenomenon:] bath and shower: [Actor:] I +

[Process:] has + [Time:] yesterday (Halliday &

Matthiessen 2014). Based on the statement above,

this article attempts to adapt the Halliday’s theory

(Halliday & Matthiessen 2014). Therefore, when

formula of transitivity is implicated in Angkola

language, there are six process types, as follows.

2.1 Material Process

The material process is a pure physical process with

no mental or behavioral elements. This material

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

24

process consists of two kinds of doing (doing

something) and happening (incident). In Angkola

language, there are four parts of the material process

namely: happening, doing, range, and passive

clauses. The constituents used for doing are actors-

process-goals, while the constituents used for

happening are actors-processes (Santosa 2003).

From the two types material process, doing

relates to transitive verb, but in Angkola language, it

is also found in imperative verb. These are the model

for this type.

Table 1: Material Process: Doing: Creative

Na

m

o

m

o tu

‘too easy’

na

m

angalehen

‘who give’

e

p

engi i

‘the money’

Circu

m

stance:

way: quality

P

r

ocess:

m

aterial:

doing creative

Goal

‘Too easy to gi

v

e

m

one

y

.’

Based on the table 1 can be described that na

mangalehen ‘who give’ is the process. It says a

material because it uses hand as a part of human

body. It called doing because a transitive verb. The

last, it named creative because it has a goal.

Therefore, this model is process: material: doing:

creative even though form of the actor is ellipsis.

Because of that, the original formula is process +

goal. Then, if we want to know where the position of

the actor in this formula, we must use the ellipsis in

this analysis to find the full formula, that is actor +

process + goal. It is just because of this oral speech

should be seen in context when to know who the actor

is meant by the data.

Table 2: Material Process: Doing: Dispositive

Lehen tong

‘give first’

p

arsigaret na

‘his cigarettes’

jolo

‘first’

Process:

material:

Goal Circumstance:

location: time

‘Give first cigarettes first.’

The model in the table 2 above, it is seen clearly

that the process is lehen tong ‘give first’. The

process is lehen ‘give’ and tong is a particle in

Angkola language but it calls with first. Lehen

‘give’ is an imperative verb because it does not use

prefix. Then, the position of process is in front of

the clause. Lehen ‘give’ is a material because its verb

uses a hand to do this process. Then, this

process called doing because have an object, so this

model can be included in transitive verb too. Last,

lehen ‘give’ named dispositive because the object

does not exist yet. Next, the original formula is

process + goal. Then, if we want to know the

location of the actor in this process, it can be

analyzed from the ellipsis actor in this data

according to the context. Therefore, the formula is

process + actor (ø) + goal.

Table 3: Material Process: Happening: Range

Na

r

on

doma

‘later’

ro da

‘come yes’

a

b

is Is

y

a

‘after Isya’

tu

b

agas

‘to

the

Cir: loc:

time

P

r

ocess:

material:

happening

Range Cir:

loc:

place

‘Later co

m

e out Is

y

a to ho

m

e.’

Model from table 3 above can be explained that

ro da ‘come yes’ is the process. Ro ‘come’ is the

verb and da ‘yes’ is the particle. Next, ro ‘come’ is

material because use feet. Then, it called happening

because it’s intransitive verb. Next, its name is

range because after ro da followed by abis Isya

‘after Isya’ which is indicates time duration.

Usually, the time is above eight o’clock. Therefore,

the formula is process + range.

Table 4: Material Process: Happening: Scope

Sugari

‘if only’

p

asuo ma

‘meet’

rap Bang

Bargot

‘with

brother

Bargot’

di dalan-

dalan on

ate da

‘in these

streets,

right.

Conj

p

rocess:

material:

happening:

Goal Range

(process

Scope)

‘Supposing I meet with brother Bargot on these

Table 4 shows that pasuo ma ‘meet’ is the

process. The process is pasuo ‘meet’ and ma is a

particle. Pasuo ‘meet’ is a material because use the

body to do this activity. It called happening because

pasuo ‘meet’ is intransitive verb. Then, it includes

to scope because it followed di dalan-dalan on ate

da ‘in these streets, right’. It means that the streets

are limited. Then, the original formula is process +

goal + range. However, to know the position of

actor we can elicits based on data context is process

+ actor (ø) + goal + range.

According to the four models above, it explains

that the material process in Angkola language, have

the same formula, they are: process + goal; process

+ goal; process + range; and process + goal +

range. These four formulas have the same pattern

that always preceded by the process in the clause.

About the participant in Angkola language,

sometimes found ellipsis form. Associated with the

circumstantial position in the clause can be

Process Type of Angkola Language Transitivity

25

anywhere. It happens because the data is spoken,

real speech, not formal style.

2.2 Mental Process

The mental process is a process of thinking, sensing,

and feeling. This process can have a classification

into three types, namely mental processes: cognitive,

perceptive, and affective. Then, in this process, there

are only two participants, senser and phenomenon

(Santosa 2003).

About mental process in Angkola language,

can described as follows.

Table 5: Perception

Ligin

b

o

‘take a look’

na dua

‘the two’

indin

‘there’

P

r

ocess:

m

ental:

perception

Pheno

m

enon:

micro

Sir: loc:

p

lace

‘Loo

k

at the two the

r

e.’

Model in table 5 shows that process is ligin bo

‘take a look’. Ligin is process and bo is a particle.

Ligin ‘take a look’ is mental because the process use

the one of the five senses (perception) which is using

the eyes. Although, it process use the imperative

verb, the original formula is process + phenomenon.

Then, if we want to know the position of senser in

this clause it can be senser (ø) + process +

phenomenon.

Table 6: Cognition

Na

p

ola

p

i

k

ir-

pikironkon

‘don’t need to think’

-mu

‘-you’

I

‘that

(matter)’

P

r

ocess:

m

ental:

cognition

-sense

r

Pheno

m

enon

: micro

‘No nee

d

to thin

k

about it.’

About model in table 6 above, it indicates that

napola pikir-pikironkon ‘don’t need to think’ is a

process. The basic verb is pikir ‘think’ that is

cognition because there is in mind unseen.

However, the interesting thing is in senser, that is

–mu ‘you’ that is attached to process. However, it

can be like inflection, process added with senser.

Therefore, the formula is process + -senser +

phenomenon.

Table 7: Affection

Bope soni

‘even though’

lek sak do

‘remain

worried’

Rohakku

‘my heart’

Conj. Process:

mental:

Sense

r

‘Though so worried my heart.’

Model in table 7 is lek sak do ‘remain worried’ is

process. The basic verb is sak ‘worry’ that is

experiencing ellipsis from marsak ‘worried’. Then,

sak ‘worried’ is a mental because unseen and called

afection because associated with feelings.

Sometimes, Angkola language have inversion

clause. Therefore, the formula is process + senser.

2.3 Verbal Process

The verbal process is a pure word process, no

element of behavior. The Indonesian word is very

limited. Usually, using the word say and ask for the

process. Furthermore, participant in this process

includes sayer, verbiage, and receiver. Sayer is

someone to say, verbiage is something to say, and

the receiver is the one receiving the verbiage

(Santosa 2003).

About verbal process in this clause described as

follows.

Table 8: Verbal

Ulang dok

k

on

‘‘don’t say’

soni

‘like that’

da

m

ang

‘ok son’

P

r

ocess ve

r

b

iage

r

eceive

r

‘Do not say it li

k

e that o

k

b

o

y

.’

Model in table 8 above has ulang dokkon ‘don’t

say’ as a process. The basic verb is dokkon ‘say’. It is

the verbal process because this verb is say

something directly. Actually, the original formula is

process + verbiage + receiver, but if we want to

know the position of sayer in this clause is pro- +

sayer (ø) + -cess + verbiage + receiver. Generally,

the verbal process has the same pattern with the

material process, that is, process first in the clause.

2.4 Behavioral Process

The behavioral process consists of two types,

namely: the process of verbal behavior and the

process of mental behavior. On the one hand, the

process of verbal behavior is a process of conduct

that verbally performs actions, such as suggesting,

claiming, discussing, explaining, make fun of,

spurning, and so on. Participants of this process are

behaver, verbiage, and receiver (Santosa 2003).

Behavioral process in Angkola language can

described as follows.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

26

Table 9: Verbal behavioral

Ulang pabua

‘Don’t tell’

au

‘i’

dison

‘here’

da ma

k

‘mom’

Process:

behavioral:

verbal

Behave

r

r

eceive

r

verbiage

‘Don’t tell me here mom.’

Model in table 9 above explains that ulang

pabua ‘don’t tell’ is process. The basic verb is

pabua ‘tell’ whereas ulang ‘don’t’ is negation. So,

pabua ‘tell’ is behavioral because it shows that the

behavior of conveying something to others.

Therefore, pabua ‘tell’ including in verbal. Next, the

formula becomes process + behaver + receiver +

verbiage.

Table 10: Mental behavioral

O..hara

na ni i

‘o..ther

efore

Ima

‘it’s’

sela

m

a na on

‘all this

time’

na

jungada

dihargai

‘never

appreciat

Ho

‘you

’

au

te

‘me

, ok’

Conj. Beha

ver

r

eceive

r

verbiage

‘Don’t tell me here mom.’

The model in table 10 above indicates that na

jungada dihargai ‘never appreciated’ is process. Na

jungada ‘never’ is negation and dihargai

‘appreciated’ is process. Dihargai ‘appreciated’ is a

behavior that shows an attitude that comes from

feelings. So, dihargai ‘appreciated’ is mental

because unseen but can be felt and seen his

expression. Therefore, the formula is -haver +

process + be- + phenomenon.

2.5 Relational Process

The relational process is the process of associating

between one participant and another participant.

The association may attribute or assign value to the

first participant. Based on this, then this process

consists of two types, namely: relational attributive

process and relational identification process.

Attributive relational process is the process of

associating

between participants who one with other

participants by providing attributes. Participants of

this process are the carrier and the attribute. Then,

the attributive identification process is the process

of associating between one participant and another

by assigning value to the participant. Participants in

this process consist of tokens and values (Santosa

2003).

Relational process in Angkola language can

described in model as follows

Table 11: Attribute

Tapi

‘But’

ma get

‘already want to be’

p

arumaenmu do

‘your daughter in

law’

Conj. Process: relational:

attributive

Attributive

‘But already want to be your daughte

r

-in-law.’

Process in table 11 is ma get ‘already want to be’.

Ma ‘already’ experiencing the ellipsis from madung

and get ‘want to be’ is the process. Get ‘want to be’ is

relational which is attributive. The formula is process

+ attribute. Because, get ‘want to be’ connect between

forms as carrier (ø) with form attribut (parumaenmu

do ‘your daughter in law’). Therefore, carrier

appearance here based on data context, so, the

formula is carrier + process + attribut.

Table 12: Identification

Ho

‘you’

do

‘is’

na gait i

‘that flirtatious’

Token Process: relational:

identification

value

‘You are the flirty.’

The model in table 12 above has do ‘is’ as a

process. Because do ‘is’ connect between ho ‘you’

with na gait i ‘that flirtatious’.So, do ‘is’ process:

relational: identification. Therefore, the formula is

token + process + value.

2.6 Existential Process

Existential process is a process that indicates the

existence of something. In Indonesian, this process

indicates a clause structure that starts with "There is

...." or "There are ...." or an "Appear" verb. This

process has one participant ie exsisten that is

something that raised (Santosa 2003).

The model of existential process in Angkola

language explained as follows.

Table 13: Existential

Adong dope

‘There are

more’

nakkin dison

‘was here’

goreng

‘fried bananas’

Process:

existential

Cir:loc:time

identification

existen

‘There's more here fried bananas.’

Process Type of Angkola Language Transitivity

27

Based on the model in table 13 above, the

process is adong dope ‘there are more’. The point is

adong ‘there are’ shows the existence of something,

that is goreng ‘fried bananas’. Then, the formula is

process + existen.

After the exposure of the models above is

generally based on the spoken data from the

Parhuta-huta’s film, it can be generalized some

formulas of process type in Angkola language

transitivity are material process, mental process,

verbal process, behavioral process, relational

process, and existential process. Habitually, process

type in Angkola language transitivity his position is

in front of the participants. It indicates that raises the

cultural theme that the Angkola community more

focus on the process in all its activities. The

tendency for the use of processes in starting clauses

(though not in all clauses) is to interpret the culture

of a straightforward, brave, and open society in

communicating.

3 IDIOSYNCRATIC

Idiosyncratic is a symptom of strangeness found in

linguistic analysis. There are some idiosyncratic in

Angkola language transitivity, from inflection,

ergative, morpheme zero, to inversion.

3.1 Inflection and Derivation

Derivation is a morpheme process that produces a

new lexeme, whereas inflection is a morpheme

process that produces different word forms from the

same lexemes (Bauer 2003). Inflection in Angkola

language often found in the clauses. For example:

mangalehen ‘give’, pasuo ‘meet’, pikir-pikironkon

‘to think’, pabua ‘tell’, and dihargai ‘appreciated’.

The explanation of this inflection described as

follows.

Lehen ‘give’ is the basic verb have inflection

mangalehen ‘to give’ because this form does not

change the word class and can be predicted. If the

verb lehen ‘give’ got prefix manga- (active verb

marker in Angkola language) as process in

transitivity, then this verb must be followed by

minimal two constituent. Then, verbs dihargai

‘appreciated’ have the basic verb that is harga

‘price’. This verb also experienced inflection with

addition of confix di- + v + -i. It means that this verb

is pasive and followed by minimal two constituent

too.

Pasuo ‘meet’ and pabua ‘tell’ are derivation

forms with addition pa- in the basic verb. These

verbs are not change the class word, but just change

the functional become imperative clause.

Then, pikir-pikironkon ‘to think’ is

reduplication, but when we translate to English

become to think. Actually, the other interpretation of

pikir-pikironkon is alot of things in mind. This is the

uniqeness too, because in Angkola language is a

reduplication but in English is not so.

3.2 Morpheme Zero

Morpheme zero (ø) often found in spoken language,

not least in Angkola language. Morpheme zero (ø) is

one of the ruler-limited constructs when the setting

component used as the basis of consideration

(Sudaryanto 1983).

Morpheme zero (ø) experienced also by

Angkola in oral speech. However, the use of

morpheme zero in the clause must determine to the

current context. The goal is avoid misinterpretation

in communication. Morpheme zero (ø) also serves as

a form of effectiveness in everyday communication.

Morpheme zero (ø) interpreted from constituents

before or after.

The example of the clause morpheme zero (ø)

described as follows. From a clause, Sugari pasuo

ma (ø) rap Bang Bargot di dalan-dalan on ate da. It

means ‘Supposing meet with brother Bargot on these

streets, right.’ In the clause is not found who the

participant is because of its shape in morpheme zero.

However, if adjusted to the context of the data,

then the participants can raised to me. Thus, the

position of the morpheme zero is after the process so

it becomes Sugari pasuo ma au rap Bang Bargot di

dalan-dalan on ate da. It means ‘Supposing I meet

with brother Bargot on these streets, right.’

Therefore, after the addition of the morpheme zero

then the meaning of that clause becomes easily to

understand by the reader.

3.3 Inversion

The inverse sentence is a reversed sentence. The

general terms are subject that is not definite. Even

farther, the inversion sentence is different from the

permutation sentence. The inversion sentence

requires the order of Subject-Predicate, whereas the

permutation sentence is only one of the styles that

selected from the standard sequence (Hasan 2003).

Related to this, the Angkola language uses both in

daily communication as follows.

However, for this time the model is bope soni

lek sak do rohakku ‘Though so worried’ (see in table

7). The formula is process + senser. It indicates that

the process first than the senser, this is inversion.

The other model, there is something very interesting,

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

28

that is on the clause napola pikir- pikironkonmu

i. It means no need to think about it (see in table

6). Actually, pikir-pikironkon ‘to think’, it is a

process and it stands alone. Then, -mu ‘you’ is a

participant tied to pikir-pikironkon ‘to think’.

Therefore, it proves that even this model has

inversion like process + senser.

3.4 Ellipsis

The ellipsis is part of the passage that refers to the

omission of a word or other unit whose original form

can be predicted from the outside context of the

language (Setiawan 2014).

One example of ellipsis can found in the

following model bope soni lek sak do rohakku

‘though so worried my heart’ (see in table 7). The

elliptical constituent is sak from marsak ‘worry’.

4 CONCLUSION

In general, this study produced two parts, namely

process type and idiosyncratic. Process type in

Angkola language transitivity taken from Parhuta-

huta’s film is six types. There are material process,

mental process, verbal process, behavioral process,

relational process, and existential process. Generally,

that the formula in Angkola language transitivity

starting from process then followed by participants.

About the idiosyncratic, Angkola language

transitivity experiencing some of the things it is

inflection and derivation, zero morpheme, inversion,

and ellipsis. Actually, this study explores a small part

of Angkola language and it requires further research

to extract more findings from the Angkola language.

Therefore, it is expected that this research will be

useful and stepping stone for Angkola language

research from the perspective of the next Systemic

Functional Linguistics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank to BELTIC 2018 for accepting and giving

me the opportunity to attend this event so I can

explore my research better. Because this article is

part of my dissertation research that I still need to

develop again. I thank to BUDI DN-LPDP RI

scholarship for sponsoring me to join BELTIC

2018. I am very grateful to the promotor and the

copromotors from Universitas Sebelas Maret

Surakarta who has supported me to participate in

this event. Lastly, I also thank to my institution,

Universitas Muhammadiyah Tapanuli Selatan which

has always supported me to this day. I really

appreciate it.

REFERENCES

Affairs, M H 2015, Kabupaten tapanuli selatan.

Alice Caffarel, E 2004, Language typology a functional

perspective, John Benjamins BV, The Netherlands,

USA.

Moore, R., Lopes, J., 1999. Paper templates. In

TEMPLATE’06, 1st International Conference on

Template Production. SCITEPRESS.

Basori, MA & Wiranegara, DA 2016, 'Fostering students’

clause awareness on reading : the exploration on

transitivity system', vol. 11, no. 1.

Bauer, L 2003, Introducing linguistic morphology,

Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh. Behnam, B &

Zamanian, J 2015, 'Genre analysis of oxford and tabriz

applied linguistics research article abstracts : from

move structure to transitivity analysis', Journal of

Applied Linguistics, vol. 6, no. 12.

Bello, U 2014, 'Ideology in reporting the ‘operation cast

lead’ , a transitivity analysis of the arab news and new

york times reports', International Journal of Applied

Linguistics & English Literature, vol. 3, no. 3, pp.

202–10.

Budiasa, I.G 2007, 'A glimpse on english and indonesian

verbal group: a sfl perspective', vol. 1, no. 1994, pp.

1–73.

Chen, S 2016, 'Exploring language and diplomatic

thinking through process types : a contrastive study on

sino-british diplomatic thinking based on the china-uk

joint declaration', vol. 5, no. 4.

District Goverment of Tapanuli Selatan 2011, Sejarah

Tapanuli Selatan.

Evangeline, S & Fomukong, A 2017, Transitivity in

stylistics : protest through animal proverbs in bole

butake ’ s and palm wine will flow, vol. 8, no. 3.

Halliday, MAK & Matthiessen, CMIM 2014, Halliday’s

introduction to functional grammar.

Hasan, A 2003, Tata bahasa baku bahasa indonesia, Balai

Pustaka, Jakarta.

Hasibuan, MF 1972, Perbandingan pantun indonesia dan

pantun angkola, Fakultas Keguruan Sastera dan Seni

Institut Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan Negeri Medan,

Padangsidimpuan.

Hermawan, B, Zenereshynta, E & Ardhernas, N 2014, 'A

visual and verbal analysis of children representation in

television advertisement', English Review: Journal of

English Education, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–11.

Hutahaean, W 2013, Suku batak angkola di kab. tapanuli

selatan.

Ikawati, E 2014, Teks dan konteks dalam kajian tradisi

lisan angkola, vol. 06, no. 02, pp. 1–14.

Kavalir, M 2016, 'Monika kavalir paralysed : a systemic

functional analysis of james joyce ’ s ‘ eveline ’

paralizirana : sistemsko-funkcijska analiza ‘ eveline ’

Process Type of Angkola Language Transitivity

29

jamesa joycea paralysed : a systemic functional

analysis of james joyce ’ s ‘ eveline ’ 2 systemic

functional', vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 165–80.

Khristianto 2015, 'The change of mental process in

thetranslation of ronggeng dhukuh paruk from bahasa

indonesia into english', vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 45–56

Koussouhon, LA 2015, 'Exploring ideational metafunction

in helon habila ’ s oil on water : a re-evaluation and

redefinition of african women ’ s personality and

identity through literature', vol. 4, no. 5.

Lima-lopes, RE De 2004, 'Transitivity in Brazilian

greenpeace ’ s electronic bulletins', pp. 413–39.

Lubis, Syahron, et al 1995, Kamus indonesia-angkola,

Pusat Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa

Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Jakarta.

Lubis, IS 2015, Tradisi martahi karejo masyarakat

angkola: kajian semiotik sosial, no. 1, pp. 99– 127.

Lubis, K 2017, Tradisi lisan marosong-osong pada

upacara perkawinan adat angkola, no. X, pp. 1– 14.

Lubis, M 2011, Radjendra chola i.

Managor, S 1995, Pastak-pastak ni paradaton masyarakat

tapanuli selatan, CV Media, Medan.

Maulina, AE 2015, Register realization in the writing of 8

th grade students of smp kesatrian semarang (a

comparative study between dialogue and recount tex ).

Mualita, G 2015, 'Kekerabatan bahasa batak toba dan

bahasa batak angkola suatu kajian linguistik historis

komparatif', Arkhais, vol. 06, no. 1, pp. 46–52.

Muhartoyo 2012, 'The functional slots of finite verb

tagmas', vol. 3, no. 45, pp. 70–80.

Muksin 2016, 'Kajian transitivitas teks terjemahan takepan

serat menak yunan dan kontribusinya terhadap materi

pembelajaran bahasa Indonesia berbasis teks di smp:

analisis berdasarkan linguistik fungsional sistemik',

vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 253–70.

Nasution, SM 2009, 'Variasi eksperensial teks

translasional mangupa bahasa mandailing - inggris',

pp. 132–5.

Putu Sutama, I Gusti Made Sutjaja, Aron Meko Mbete, M

n.d., 'Marriage ritual text of balinese traditional

community: an analysis of functional systemic

linguistics', no. 2

Rosmawaty 2011, Tautan konteks situasi dan konteks

budaya: kajian linguistik sistemik fungsional pada

cerita terjemahan fiksi ‘halilian’.

Santosa, R 2003, Semiotika sosial, pandangan terhadap

bahasa, Pustaka Eureka, Surabaya

Setiawan, dkk 2014, Sintaksis bahasa indonesia,

Universitas Terbuka, Tangerang Selatan.

Spradely, J.P 1980, Participant observation, Holt,

Rinehart, and Winston, New York.

Sudaryanto 1983, Predikat-objek dalam bahasa indonesia,

Penerbit Djambatan, Jakarta.

Sujatna, ETS 2012, 'Applying systemic functional

linguistics to bahasa indonesia clauses', International

Journal of Linguistics, vol. 4, no. 2.

T. Ledua Alifereti, V 2013, 'An investigation of verticality

in tertiary students’ academic writing texts: a systemic

functional perspective', International Journal of

Applied Linguistics & English Literature, vol. 2, no. 3,

pp. 163–75.

Moore, R., Lopes, J., 1999. Paper templates. In

TEMPLATE’06, 1st International Conference on

Template Production. SCITEPRESS

Thompson, G 2013, Introducing functional grammar, 3rd

edn, Routledge, New York.

Tinggibarani, S 2008, Bahasa angkola, 1st edn,

Padangsidimpuan.

Valipour, V, Aidinlu, NA & Asl, HD 2017, 'The journal of

english language pedagogy and practice investigating

lexico-grammaticality in academic abstracts and their

full research papers from a diachronic perspective',

vol. 9, no. 19, pp. 179– 98.

BELTIC 2018 - 1st Bandung English Language Teaching International Conference

30