Bullous Pemphigoid Established by Direct Immunofluorescence: Case

Report

Vidyani Adiningtyas, Hasnikmah Mappamasing, Septiana Widyantari, Trisiswati Indranarum,

Sawitri, Evy Ervianti, Sunarko Martodiharjo, Dwi Murtiastutik

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga / Dr. Soetomo General Hospital

Surabaya

Keywords: bullous pemphigoid, autoimmune, subepidermal blistering, direct immunofluorescence, anti-BP180/230.

Abstract: Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease of the skin and

mucous membranes. It is characterized by autoantibodies against hemidesmosomal proteins of the skin and

mucous membranes. Collagen XVII and dystonin-e have been identified as target antigens. BP is usually a

chronic disease, with spontaneous exacerbations and remissions.

The diagnosis of BP relies on

immunopathologic findings, especially based on both direct and indirect immunofluorescence microscopy

observations, as well as on anti-BP180/BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). The

primary objectives are therefore to control both the skin eruption and itch, as well as to minimize any

serious side-effects of the treatment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Bullous pemphigoid affects mostly the elderly

(Wojnarowska et al., 2002; Di Zenzo et al., 2012).

The incidence of the disease is increasing gradually

and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Clinically, BP is characterized by an intensely

pruritic eruption with widespread bullous lesions.

The clinical diagnosis can be challenging in the

setting of atypical presentations. Both the morbidity

of bullous pemphigoid and its impact on quality of

life are significant (Bernard et al., 2017).

Treatment

is mainly based on topical and/or systemic

glucocorticoids, but anti-inflammatory antibiotics

and steroid sparing adjuvants are useful alternatives.

Localized and mild BP can be treated with topical

corticosteroids alone (Bastuji-Garin et al., 2011;

Culton et al., 2012). Specifically, the goals of the

management are: (i) to treat the skin eruption, reduce

itching and prevent/reduce the risk of recurrence; (ii)

to improve the quality of life of patients; and (iii) to

limit the side-effects related to the newly introduced

drugs, particularly in the elderly (Wojnarowska et

al., 2002; Schmidt et al., 2012).

2 CASE

This case involved a 74 year-old male, whose chief

complaint consisted of pain and erosions all over his

body. This had been occurring for two weeks.

Previously – one month earlier – there had been

tense blisters on his chest, containing clear fluid.

These were not easily broken but several of the

blisters became eroded and pain was present in the

eroded skin. Itchiness was minimal. There was no

odour and no wound on the lips or genitalia. The

patient also had a history of diabetes mellitus. His

routine activity was cycling in the morning until

noon. Dermatological examination revealed tense

seropurulent bullae on non-sharply marginated

erytematous macule. Bullae size varied from small

to 2cm. Despite some erosion and thin scales, there

was negative Nikolsky sign, no mousy odour and no

lesions on the genitalia or lips. Upon the patient’s

admission, blood, urinary, electrolyte, liver and renal

function tests were all performed and found to be

within normal limits. Albumin, eosinophil and

random blood glucose were abnormal. From the

histopathological examination, the result was

bullous pemphigoid and the direct

immunofluorescent test found linear IgG and C3 in

the basal membrane zone. The patient was treated

Adiningtyas, V., Mappamasing, H., Widyantari, S., Indranarum, T., Sawitri, ., Ervianti, E., Martodiharjo, S. and Murtiastutik, D.

Bullous Pemphigoid Established by Direct Immunofluorescence: Case Report.

DOI: 10.5220/0008157103470350

In Proceedings of the 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology (RCD 2018), pages 347-350

ISBN: 978-989-758-494-7

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

347

with methylprednisolone 4mg 3x16mg and dapsone

1x100mg daily, tapering off the steroid after there

were signs of clinical improvement including no

new lesions.

3 DISCUSSION

Figure 1: Gram staining reveals leukocyte only, without

any coccus

The name ‘bullous pemphigoid’ (BP) is a pleonasm,

as ‘pemphigoid’ is derived from Greek and means

‘form of a blister’ ( pemphix, blister, and eidos,

form) (Feliciani et al., 2015).

Bullous pemphigoid typically occurs in patients

over 60 years of age, with a peak incidence

occurring among those patients in their 70s. There

are several reports of bullous pemphigoid in infants

and children, although this is rare

(Wojnarowska et

al., 2002; Culton et al., 2012; Di Zenzo et al., 2012;

Bernand & Antonicelli, 2017).

This is consistent

with the patient in our case; he is 74 years old. Old

age is the major risk factor for the occurrence of BP.

Most cases of bullous pemphigoid occur

spontaneously without any obvious precipitating

factors. However, there are several reports in which

bullous pemphigoid appears to be triggered by

ultraviolet (UV) light, either UVB or following

PUVA therapy, and radiation therapy. Certain

medications have also been associated with the

development of bullous pemphigoid including

penicillamine, efalizumab, etanercept, and

furosemide (Batsuji-Garin et al., 2011; Culton et al.,

2012; Bernand & Antonicelli, 2017).

Since the patient stated that he routinely cycles

every morning until 10am and never wears a hat or

applies sun protection, we suggest that one possible

trigger might be UV light. In addition, various

autoimmune disorders, psoriasis, and neurologic

disorders have also been described in association

with BP (Lipsker & Borradori et al., 2010; Venning

et al., 2012).

The patient’s chief complaint consisted of

blisters, erosion and pain on his body. Upon

examination, tense bullae on erythematous macule

were discovered. These were non-sharply

marginated, contained clear fluid, were not easily

ruptured and were Nikolsky- and Asboe Hansen-

sign negative. Eroded skin was widespread on the

body from the ruptured blister; crust, scales and

xerosis were also discernible on the body. This is

consistent with the literature: clinical criteria BP

typically presents with tense, mostly clear skin

blisters, in conjunction with erythematous or

urticarial plaques that are associated with moderate

to severe pruritus.

4

Although the pruritus was

minimal in this patient. pruritus may be intense in

some patients, but minimal in others. These lesions

are most commonly found on flexural surfaces such

as the lower abdomen and thighs, although they may

occur anywhere (Culton et al., 2012). Predilection

sites in the patient include the limbs and abdomen.

The mucosae of eyes, nose, pharynx, oesophagus

and anogenital areas are rarely affected (Culton et

al., 2012; Venning et al., 2012).

Figure 2: on regio cruris dextra et sinistra: tense blisters on

erythematous macule; these were non-sharply marginated,

contained clear fluid and were not easy to break.

Nikolsky- and Asboe Hansen-signs were negative.

Erosion, scales and crust were found.

RCD 2018 - The 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology 2018

348

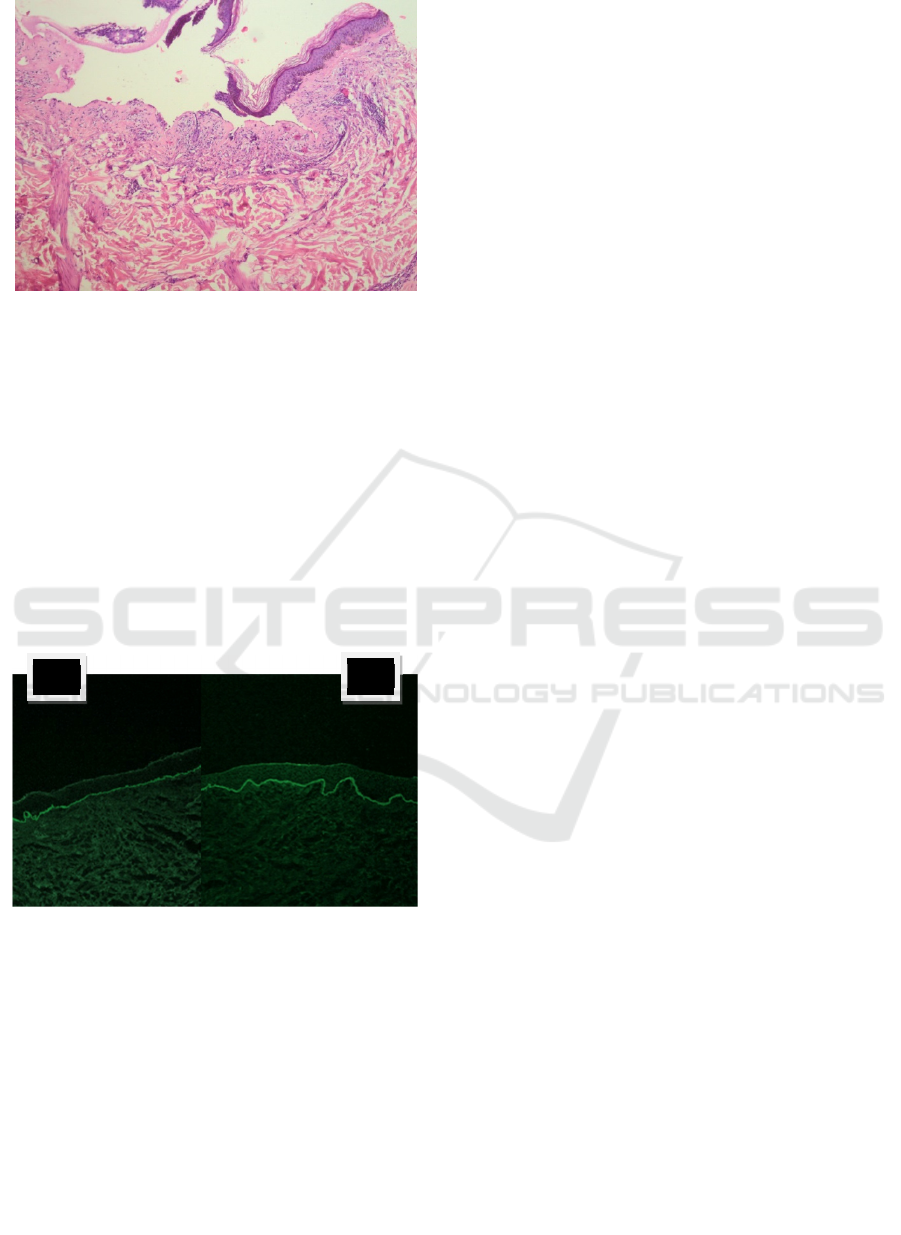

Figure 3. Histopathology examination with hematoeosin

staining, subepidermal blister with with inflammatory

infiltrate numerous eosinophil and several neutrophil,

100x magnification.

The hallmarks of bullous pemphigoid include the

presence of subepidermal blisters, lesional and

perilesional polymorphonuclear cell infiltrates in the

upper dermis and immunoglobulin (Ig) G

autoantibodies and C3 bound to the dermal

epidermal junction. Direct IF of perilesional skin

shows linear IgG (usually IgG1 and IgG4, although

all IgG subclasses and IgE have been reported) and

C3 along the basement membrane (Venning et al.,

2012; Zhao & Murrell, 2015).

Figure 4: Direct imunoflourescence examination. A. C3 B.

IgG

Diagnosis was made from anamnesis, physical

examination, laboratory examination, histopat

hology and direct immunofluorescence. The

diagnosis in this patient was bullous pemphigoid,

hypoalbuminemia and diabetes mellitus (DM) type

2.

Treatment was immediately started:

methylprednisolone 4mg in oral dosage 3 times 3

tablets daily (12mg-12mg-12mg) tapering off

depending on the progression of the lesion to find

maintenance dosage; dapsone 100mg once daily;

wound dressing using NaCl 0.9% on erosion lesion;

insulin injection as advised from internal medicine

department; insulin novorapid injection 3x6iu;

insulin levemir 1x8iu morning dosage only; backup

insulin 2iu with every 12mg methylprednisolone;

Vitamin D 300iu; calcium carbonat 600mg; diet B1

2100kkal/day; and high protein diet for the

hypoalbuminemia.

4 CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid is made based

upon clinical, histologic, and immunofluorescence

(IF) features (Schmidt & Groves, 2016). The initial

evaluation of patients should encompass a complete

physical examination and, wherever possible, the

assessment of the initial damage (Bernard &

Antonicelli, 2017).

For decades, systemic corticosteroids have been

used and considered as the gold standard for the

treatment of this disease, especially for generalized

BP (Schmidt et al., 2016). Immunosuppressive

therapy with corticosteroid-sparing effects should be

considered a second-line therapy when

corticosteroids alone fail to control the disease, or in

cases of contraindications to oral corticosteroids and

comorbidities (such as diabetes, severe osteoporosis

and cardiovascular disorders) (Bower, 2010). Unless

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency is

evident, the use of dapsone (up to 1.5 mg/kg/day

orally) may also be warranted, generally in

association with topical or systemic corticosteroids,

especially in the presence of mucosal involvement.

In elderly patients, the complications of systemic

glucocorticoid therapy (such as osteoporosis,

diabetes, and immunosuppression) may be

especially severe (Bouscarat et al, 2006; Bagci et

al.,2017). Therefore, it is important to try to

minimize the total dose and duration of therapy with

oral glucocorticoids (Culton et al., 2012; Bernand &

Antonicelli, 2017).

REFERENCES

Bağcı, I.S., Horváth, O.N., Ruzicka, T., Sárdy, M., 2017.

Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmunity Reviews.

doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.03.010

Bastuji-Garin, S., Joly, P., Lemordant, P., Sparsa, A.,

Bedane, C., Delaporte, E., Roujeau, J.C., Bernard, P.,

Guillaume, J.C., Ingen-Housz-Oro, S., Maillard, H.,

Pauwels, C., Picard-Dahan, C., Dutronc, Y., Richard,

M.A., French Study Grp Bullous, D., 2011. Risk

A

B

Bullous Pemphigoid Established by Direct Immunofluorescence: Case Report

349

Factors for Bullous Pemphigoid in the Elderly: A

Prospective Case-Control Study. Journal of

Investigative Dermatology 131, 637–643.

doi:10.1038/jid.2010.301

Bernard, P., Antonicelli, F., 2017. Bullous Pemphigoid: A

Review of its Diagnosis, Associations and Treatment.

American Journal of Clinical Dermatology.

doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0264-2

Bouscarat, F., Chosidow, O., Picard-Dahan, C., Sakiz, V.,

Crickx, B., Prost, C., Roujeau, J.C., Revuz, J., Belaich,

S., 1996. Treatment of bullous pemphigoid with

dapsone: Retrospective study of thirty-six cases.

Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 34,

683–684. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(96)80085-5

Bower, C. 2010. Bullous pemphigoid: guide to diagnosis

and treatment. Prescriber. 17(12):44-50.

Culton, D.A., Diaz, L.A., Liu, Z. 2012. Bullous

pemphigoid. In: Goldsmith L. Fitzpatrick T(ed).

Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 1st ed.

New York: McGraw-Hill Medical.

doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 P 608-16

Di Zenzo, G., della Torre, R., Zambruno, G., Borradori,

L., 2012. Bullous pemphigoid: From the clinic to the

bench. Clinics in Dermatology 30, 3–16.

doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.005

Feliciani, C., Joly, P., Jonkman, M.F., Zambruno, G.,

Zillikens, D., Ioannides, D., Kowalewski, C.,

Jedlickova, H., Kárpáti, S., Marinovic, B., Mimouni,

D., Uzun, S., Yayli, S., Hertl, M., Borradori, L., 2015.

Management of bullous pemphigoid: The European

Dermatology Forum consensus in collaboration with

the European Academy of Dermatology and

Venereology. British Journal of Dermatology 172, 867–

877. doi:10.1111/bjd.13717

Lipsker, D., Borradori, L. 2010. ‘Bullous’ Pemphigoid:

What Are You? Urgent Need of Definitions and

Diagnostic Criteria. Dermatology. 221(2):131-134.

Schmidt, E., della Torre, R., Borradori, L., 2012. Clinical

Features and Practical Diagnosis of Bullous

Pemphigoid. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North

America. doi:10.1016/j.iac.2012.04.002

Schmidt, E., Groves, R. Bullous pemphigoid. In: Griffith,

C., Barker, J., Bleiker, T., Chlamers, R., Creamer D.

2016. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology.9

th

ed.Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

50.11-20

Schmidt, E., Zillikens, D., 2013. Pemphigoid diseases. The

Lancet 381, 320–332. doi:10.1016/S0140-

6736(12)61140-4

Venning, V.A., Taghipour, K., Mohd Mustapa, M.F.,

Highet, A.S., Kirtschig, G., 2012. British Association

of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of

bullous pemphigoid 2012. British Journal of

Dermatology. doi:10.1111/bjd.12072

Wojnarowska, F., Kirtschig, G., Highet, a S., Venning, V.

a, Khumalo, N.P., 2002. Guidelines for the

management of bullous pemphigoid. The British

journal of dermatology 147, 214–21.

Zhao, C.Y., Murrell, D.F., 2015. Advances in

understanding and managing bullous pemphigoid.

F1000Research. doi:10.12688/f1000research.6896.1

RCD 2018 - The 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology 2018

350