Investigating Knowledge Management in the Software Industry: The

Proof of Concept’s Findings of a Questionnaire Addressed to Small

and Medium-sized Companies

Danieli Pinto

1

, Mariana Oliveira

1

, Flávio Bortolozzi

1,2

, Nada Matta

3

and Nelson Tenório

1,2,3

1

Knowledge Management Master’s Program of UniCesumar, Av. Guedner, 1218, build 7, Maringá, Paraná, Brazil

2

Institute Cesumar of Science, Technology, and Innovation, Av. Guedner, 1218, build 11, Maringá, Paraná, Brazil

3

University of Troyes, 12 rue Marie Curie, Troyes, France

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Proof of Concept, Questionnaire, Software Industry.

Abstract: The software industry is dynamic and complex, so they need to use the knowledge to excel in a highly

competitive market. Thus, the knowledge well managed brings the organization a sustainable and

competitive advantage. Knowledge Management (KM) processes can avoid knowledge lost since they

provide knowledge flow for the whole organization. These processes are supported by practices and tools

promoting the creation, retention, and dissemination of the knowledge within the organizational

environment. The objective of this study was to validate, through a proof of concept (POC), a questionnaire

to investigate the processes, practices, and tools of KM in SME-Soft. The questionnaire was evaluated by

fifty-one professionals and KM experts from the software industry. Our findings point out that the

questionnaire is suitable for the software industry.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the last few years, the organizations recognize

the knowledge as an asset which adds value to

products and services. In this sense, the knowledge

has been considered relevant for the business

advantage (Del Giudice and Maggioni, 2014). Thus,

the individuals are responsible for encouraging

content creation and the updating of existing

knowledge (Chang and Lin, 2015). The Knowledge

Management (KM) sets an approach to ensure the

full usage of the organization’s knowledge base

(Dalkir, 2011). So, KM is crucial to maintaining and

enhancing the performance of organizations

(Muthuveloo et al., 2017), becoming relevant to

integration between developing software and its

operational deployment (Colomo-Palacios et al.,

2018).

The software industry companies are

characterized as highly-competitive, dynamic, and

activities that use knowledge intensively (Nawinna,

2011). Aurum et al. (2008) state that the knowledge

circulating within a software development teams is

dynamic and evolves according to technology,

organizational culture, and changes in software

development processes. Thus, KM prevents those

organizations of knowledge loss (Bjornson and

Dingsoyr, 2008). Therefore, regardless of the size of

the company successful results in creating and

maintaining software depends on the KM since the

individuals’ knowledge is directly related to the

product development, management, and technology

(Aurum et al., 2008).

In this scenario, small and medium-sized

software industry companies (SME-Soft) which their

success is directly related to the knowledge,

experience, and skills of their owners and employees

(Wee and Chua, 2013). Thus, SME-Soft is not able

to practice KM in the same way as large

organizations due to its organizational culture and

structure. Like that, it is relevant to investigate the

practices, processes, and tools that SME-Soft to keep

their knowledge flowing.

Previous research has established means to

investigate KM process within organizations,

providing a diagnosis of the KM processes and

practices such as Bukowitz and Willians (1999),

Vestal (2002), Fonseca (2006), and Nair and Prakash

Pinto, D., Oliveira, M., Bortolozzi, F., Matta, N. and Tenório, N.

Investigating Knowledge Management in the Software Industry: The Proof of Concept’s Findings of a Questionnaire Addressed to Small and Medium-sized Companies.

DOI: 10.5220/0006925000730082

In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2018) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 73-82

ISBN: 978-989-758-330-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

73

(2009). However, those works were not mainly

designed to investigate KM within the SME-Soft.

Besides, the proposals follow specific

methodologies to be carried on and too

overwhelming to be answered, requiring the help of

an expert. Moreover, the outcomes of those

proposals also require much time to be understood

and interpreted.

Therefore, this paper aims to validate and refine a

questionnaire to investigate the processes, practices,

and tools of KM within SME-Soft. For this, we

carried out a proof of concept (POC). The POC is a

best practice to improve questionnaires or tools in

both experimental studies and commercialization of

new technology products, helping to identify

problems which compromises the results of studies

(Kendig, 2016). The POC works as ‘pre-test’ of the

questionnaire, evidencing deficiencies, such as

ambiguous, poorly designed or double (Aaker et al.,

2001). Thus, the POC provides the sense concerned

its structure, content, applicability, and of how long

each participant takes to answer it.

The remainder of this paper is structured as

follows. In the next section, we present the related

works of investigating KM in the organizations

through the questionnaires. Section 3 presents our

method to design the questionnaire and to perform

the POC. Section 4 presents the results of our paper

and, finally, section 5 presents our conclusions

followed by the references.

2 RELATED WORKS

A way to find out where is the knowledge and how

individuals use it within the organization is

identifying the KM process. According to Oliva

(2014), as important as understanding where

knowledge is revealed, is to understand where

knowledge is established. In this sense, evaluating

KM practices in an organization means measuring

what has been done by it (Khatibian et al., 2010).

Demchig (2015) states that KM means

understanding and deepening knowledge about

organizational processes and what their

contributions to knowledge generation are. The

author emphasizes that knowledge is an asset of

constant evolution and as organizations share new

experiences, they learn, and advance and then the

new understandings are gained.

Siadat et al. (2016) state the need to map the

relationship between theory and KM practices

carried out by the organization to show how it

works, how it performs its operations and also the

path covered by the information and knowledge.

Khatibian et al. (2010) show that many

organizations are practicing KM, but they do not

recognize their practices as a relevant context

organizational, while other organizations even speak

about practices but use minimal efforts to achieve

success. Freeze and Kulkarni (2005) go on that KM

is not just a management of intellectual assets, but

also the processes that act on them including the

development, storage, use and, especially, sharing

knowledge which, in this case, involves the

identification and analysis of availability and

desirable assets, with the sole purpose of achieving

the organizational objectives.

Bukowitz and Willians (1999), Vestal (2002),

Fonseca (2006), Nair and Prakash (2009), and APO

(2009) propose different models to investigate KM

process and practices within the organizations.

Those models aim to diagnosis how the organization

manages and controls its knowledge (Freeze and

Kulkarni, 2005) through an organizational

knowledge overview (Siadat et al., 2016).

In this sense, Bukowitz and Willians (1999)

propose a KM diagnosis through a set of subjective

questions to the organization. All the questions are

then later ranked, tabulated, interpreted, and

discussed. The authors divide the KM diagnostic

model into two dimensions namely tactical and

strategic. The tactical dimension is consisting of the

knowledge obtaining, using, learning, and

contributing. The strategic dimension consisting of

the evaluate, build and maintain the knowledge

within the organization.

Vestal (2002) provides a detailed roadmap to

help organizations design, implement, and sustain

their knowledge addressed either by organizations

that are implementing or have already implemented

KM. First, the model provides the step-by-step for

the development and implementation of the strategy.

Second, the model acts as an adjustment tool,

providing a diagnosis of the knowledge situation in

the organization. For this, the model presents four

phases namely call to action, development of the

KM strategy, design and implementation, and

expansion and support.

Fonseca (2006) proposes the model called

Organizational Knowledge Assessment Methodology

(OKA) in which aims to assess and measure the

performance of an organization concerning KM

through a questionnaire. The model has three

dimensions based on people, processes, and systems,

and the results, presented in a radar chart, show the

strengths and weaknesses of the KM in the

organization.

KMIS 2018 - 10th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

74

Nair and Prakash (2009) propose the Knowledge

Management Facilitators’ Guide. The authors

suggest a methodology for the implementation of

KM addressed to small and medium-sized. The

method consists of three levels namely accelerators,

KM processes, and results.

While supporting KM investigation and

diagnosis through the questionnaires, most of the

models are split into different dimensions. Those

dimensions aim to identify some improvement

points categorizing the results of the KM models

used for facilitating its interpretation and

understanding. In this sense, Pinto et al., (2016)

suggest six dimensions to investigate KM within

SME-Soft as follows.

KM Perception Dimension. According to

Davenport and Prusak (1998), KM has to support

companies’ strategic plans explicitly. Moreover, KM

establishes the understanding regarding individuals’

knowledge to be used and aid the decision-making

processes within the companies (Serna et al., 2017).

Thus, this dimension aims to investigate the

participant’s perception regarding KM within their

organization.

Organizational Knowledge Identification

Dimension. This dimension is essential to investigate

if the individuals know where they find the

knowledge which they need. The companies’

knowledge is unique, i.e., there are not two or more

companies with the same knowledge (Capaldo and

Petruzzelli, 2015). In this sense, it is crucial to

identify the organizational knowledge and map it in

the organizational environment. Therefore, this

dimension aims to investigate the flow of the

organizational knowledge and shows its origin.

Organizational Knowledge Storage Dimension.

This is addressed to store individual knowledge

getting it explicit through different means such as

documents, manuals, databases, etc. Wiig (1993)

states that the companies’ knowledge must be stored

in knowledge bases or repositories to become

explicit. Thus, knowledge associated with abstract

concepts is coding by experts and indexing in

databases to make it more tangible for the whole

members of the organization. Thus, this dimension

aims to investigate ‘where’ and ‘how’ the

knowledge is stored, and what kind of tools the

companies use to store their knowledge.

Organizational Knowledge Recovery Dimension.

This dimension consists of retrieving the stored

knowledge to supply the individual’s needs

regarding information (Yagüe et al., 2016).

Moreover, the information retrieved give the

individuals means to build a new knowledge (Choo,

2006). Thus, this dimension presented aims to

investigate the knowledge recovery checking

whether individuals usually recover the knowledge

stored in the organization.

Organizational Knowledge Sharing Dimension.

It considers that the organizational knowledge is

dynamic and dependent on social relationships for

knowledge creation, sharing, and use (Ipe, 2003).

Furthermore, the organizations have different

individuals with different expertise, experience, and

necessities. So, the knowledge cannot be lost, and it

is necessary for the organizations to stimulate

sharing practices offering favorable conditions for

creation, sharing and use of the knowledge (Zhang

and Jiang, 2015). So, this dimension aims to enhance

the organizational knowledge among the individuals.

Finally, KM Practices and Tools Dimension. KM

practices are a set of activities conducted by the

organization to improve the effectiveness and

efficiency of the organizational knowledge resources

(Andreeva and Kianto, 2011). On the other hand, the

tools aim to support those practices. Perez-Aros et

al. (2007), go on that “tools must support

communication appropriately, collaboration, sharing

and searching activities related to relevant

information and knowledge”. Therefore, this

dimension aims to identify how often which

companies use the KM practices and also what sort

of tools are used to subsidize these practices.

While offering useful means to investigate and

diagnosis KM within the organizations, the

questionnaires suggested by the previous works are

too complex, extensible, and not focused on SME-

Soft once they not contain specific questions to

software development companies. In this sense, we

present our questionnaire addressed to SME-Soft,

and validated and refined by a POC.

3 METHOD

The questionnaire was grounded based on previous

works by Bukowitz and Willians (1999), Vestal

(2002), Fonseca (2006), Nair and Prakash (2009),

and Pinto et al. (2016), and the questions are

addressed investigate KM processes, practices, and

tools within SME-Soft. We present the complete

questionnaire in the Appendix.

3.1 Questionnaire Design

We designed the questionnaire according to steps

suggested by Aaker et al. (2001). Afterward, we

organized the questionnaire in Google Forms tool

Investigating Knowledge Management in the Software Industry: The Proof of Concept’s Findings of a Questionnaire Addressed to Small

and Medium-sized Companies

75

arranging it in two sections to facilitate data

collection and analysis. The first section brings

questions about the profile of the participants

through sixteen questions regarding education, age,

gender, how long the participant works in the

organization, and position. The second section in six

dimensions proposed by Pinto et al., (2016). The

dimensions were structured considering that the

knowledge of the organizations is inside the people

and needs to be identified, organized and stored so

that it is not lost, and can be recovered and shared

whenever necessary. Table 1 presents an overview

of the questionnaire before the POC showing the

sections and dimensions followed by its goals and a

description of the questions. Finally, the Appendix

presents the complete questionnaire.

3.2 Data Collection

The participants were invited to cooperate with this

research during a software local productive

arrangement meeting attended by companies'

members located in the Northwest Region of Paraná,

Brazil. The local productive arrangement has more

than three hundred small and medium-sized

companies associated. At the meeting were present

members of fifty-three companies in which ten of

them got interested in collaborating with the

research. All participating companies are software

vendors having between 10 and 25 years old

operating in the market with local clients and also

clients across Brazil. After the meeting, we e-mailed

the participants a brief of the research containing

goals, methods, data needs to collect, and the time

estimation for each participant to answer and assess

the questionnaire. The companies could point out the

individuals to participate in the POC according to

their availability. The questionnaire was assessed

following a scheduled. We designed seven questions

which were used as a driver of the questionnaire

assessment as follows.

1. How long did you take to answer the

questionnaire? Do you think this time to

respond was reasonable?

2. Do the questions fit for the software industry?

3. Does the questionnaire fit for the software

industry?

4. Would you rule out a question? Why?

5. Would you add any questions? Why?

6. Is the questionnaire relevant to your organiza-

tion?

We carried on data collection between July and

August of 2016. We visited each company, we

accessed the questionnaire in the Google Forms, and

then we ‘gave’ the questionnaire to each participant

answer it by themselves in a private room. All

participants data were kept in secrecy, and we

cannot identify them through the answers. Each

participant also received a hard copy of the

questionnaire, which made it possible to follow up

the questions and some notes during the POC. We

also invited a KM expert to assess the questionnaire

in which we just emailed it to this person.

3.3 Data Analysis

We organized all the data into spreadsheets. Firstly,

we analyzed the first section of the questionnaire

regarding the profile of the participants, e.g.,

education, age, gender. Secondly, we analyzed the

answers to the six dimensions in order to identify the

processes, practices, and tools of the participants.

Finally, we analyzed the questionnaire assessment

by the participants carefully through the content

analysis technique as suggested by Neuendorf

(2016) and our empirical findings are described

following.

4 RESULTS

The POC was answered by fifty-one workers from

different software companies and one KM expert

with over 20 years of experience in academic

research. The profile of the POC participants is

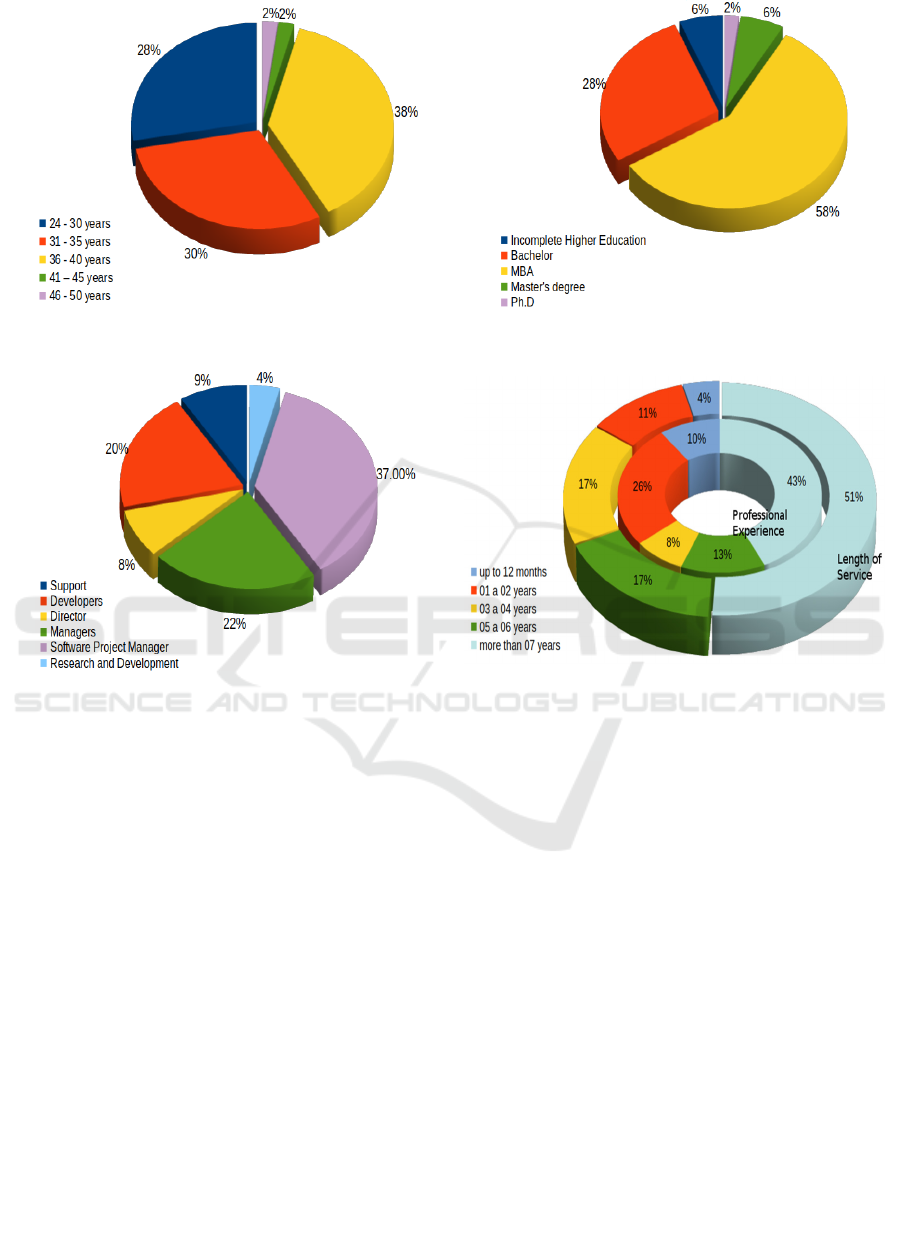

presented in Figure 1.

The Figure 1(a) shows the age of participants

ranged between 24 and 50 years old. The largest age

group was between 36 and 40 years, i.e., 38% of the

participants. The Figure 1(b) presents the degree of

education of the participants in which 28% are

bachelors, 57% have MBA in the area in which they

work, and 8% have master’s or Ph.D.

Moreover, the Figure 1(c) shows that 37% of the

participants are project managers, 16% are software

development, and 28% is responsible for any area,

e.g., leadership team, director, and CEO. Finally, the

Figure 1(d) shows that 85% of them have worked for

the current company for more than three years, and

43% of them have experience in their current

position for more than seven years. Therefore, all

research participants have a precise knowledge of

their position within the organization.

KMIS 2018 - 10th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

76

Table 1: Overview of the questionnaire before the POC.

Section Dimension Goal Description

Background

questions

Sample

characteristics

Identify the profile of the

participants.

There were sixteen questions related to age,

gender, education, the position held in the

company, time of experience in the position, and

working time.

KM within

SME-Soft

KM Perception

(KMP)

This dimension aims to show

the participant’s perception

of the knowledge and the

KM within the

organizational environment.

There were thirteen yes or no affirmations and

one open question to investigate the perception

of the KM's concept, relevance of the knowledge

for the organization, knowledge usage within the

organization, practice of KM,

areas/department/sectors where KM is practiced,

KM practices and monitoring by the

organization, and whether KM is a part of the

management organization strategy.

Organizational

Knowledge

Identification

(OKI)

This dimension aims to

verify if knowledge

identification is a practice

within the organization.

There were eight questions which six adapted

Likert Scale (Likert, 1932), two yes or no, and

two open questions. All of them addressed to

investigate the frequency in which the

organizational problems are solved, how often

problem solvers use the sources of knowledge,

whether team members know where to get a

knowledge required, whether all team members

express their ideas, and whether ideas are used in

the software development process.

Organizational

Knowledge

Storage (OKST)

This dimension aims to

investigate if the

organization stores a

knowledge acquired.

There was one open question, one adapted Likert

Scale question (Likert, 1932), and two yes or no

questions. All of them related to the storage and

maintenance of knowledge within the

organization.

Organizational

Knowledge

Recovery (OKR)

This dimension shows if

stored knowledge is

recovered within the

organization.

There was one adapted Likert Scale question

(Likert, 1932), and one open question to

investigate knowledge recovery by the

individuals.

Organizational

Knowledge

Sharing (OKSH)

This dimension investigates

if the knowledge is shared

and comprehensive among

the team members within the

organization.

There were five yes or no questions and one

adapted Likert Scale question (Likert, 1932)

regarding organizational motivation to store

knowledge, exchange information between team

members and other individuals in the

organization or the external environment.

KM Practices and

Tools (KMPT)

This dimension presents

which practices and tools,

currently used by people, are

aligned with KM within the

organization.

There were twenty classic Likert Scale

affirmations (Likert, 1932) related to the KM

practices carried out in the organization (e.g.,

knowledge coffee, capturing ideas, coaching, a

bank of individual skills, as well as the

evaluation of the competency management

system and reporting questions). Also, there

were nineteen classic Likert Scale (Likert, 1932)

affirmations regarding tools to support the

practices of KM (e.g., database, blogs, skype,

handbooks, notice board, chat, facebook

messenger, reports, virtual bulletin board, video,

virtual forums, Kanban, virtual collaboration,

text, intranet, Canvas, e-mail, WhatsApp, official

documents).

Source: The authors.

Investigating Knowledge Management in the Software Industry: The Proof of Concept’s Findings of a Questionnaire Addressed to Small

and Medium-sized Companies

77

(a) Age of the Participants (b) Education of the Participants

(c) Position of the Participants in the Company (d) Length of Service Professional Experience

Figure 1: Profile of the participants.

4.1 POC Findings

The POC of the questionnaire resulted in interesting

findings in which we divided in five categories as

answer time, remove questions, add questions,

relevance of the question, relevance SME-Soft, and

further considerations.

Answer time. One of questionnaire strength

reported by the participant is its answer time. We

took the answer time of the participants, and they

took around 18 minutes to answer all questions on

average. The shortest recorded time was of 14

minutes (P13, project manager) and the highest of

was 42 minutes (P14, user support manager).

Considering the questionnaire's answer time, the KM

expert pointed out that it was quite reasonable.

Removing questions. The participants suggested

removing questions in the dimension OKI. A

development leader observed two questions

investigating similar subjects, i.e., questions 2.4 and

2.8 (see Appendix). A human resource manager and

a project manager also observed those similar

questions, and the project manager highlighted that

“similar questions could discourage the participants

to continue answering the questionnaire”. Moreover,

three of the participants suggested to keep one of the

questions and discard the other, since both were

similar, but none of them indicated which question

to exclude. Inversely, the KM expert observed that,

although some questions are similar, there were no

reasons to take out those questions since they appear

in different dimensions with different goals.

However, the KM expert suggested changing the

order of the questions in the first dimension,

observing that the sequence could be more

systematic and logical.

Adding questions. When we asked the

participants regarding the needs to add questions, a

project manager suggested adding one question

exploring which companies adapt to address the

problems that arise when performing their daily

activities. An operation manager said he would not

KMIS 2018 - 10th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

78

add anything, however, stressed that the terms used

to investigate actions and practices sometimes

confuse. Still, for that manager, this is a

disadvantage for those who do not know what KM

is. An administrative leader said that some open

question should be added in the KMPT dimension to

investigate the use of other practices that are not

listed in the questionnaire. Also, another project

manager missed some questions about the results

obtained with the KM tools usage and the

performing of KM practices. Inversely, the KM

expert did not miss any questions.

Relevance for SME-Soft. All participants

observed that the questionnaire is entirely relevant

for SME-Soft. For instance, one of the project

managers considered conducting the questionnaire to

his team to ‘perceived what needs to be improved’.

In this context, the participant human resource

manager stressed that the questionnaire provides a

step forward. Another project manager and

administrative manager pointed out that the

questionnaire is provocative once they need to think

about whole organizational processes.

Further considerations. The participants made

further considerations regarding the questionnaire. A

software developer observed that the questions in

dimension OKST and OKSH looked like similar,

and those dimensions could be unified. Besides, a

support manager suggested changing the word

‘organization’ for all questions by ‘your department’

or ‘your team’ to be more specific and to get the

questions clearer. Curiously, all the participants

observed that they got some insights while

answering the questionnaire. For them, the

questionnaire increases the visibility of the

respondents regarding KM processes, practices, and

tools leading them to reflect about the organization

processes, recognizing KM tools usage, and getting

ideas how the KM could open new grounds if

applied within their team. It reinforces the

importance of a questionnaire addressed specifically

for SME-Soft.

4.2 Refining the Questionnaire

After the POC, we analyzed all the participants’

considerations and carried out following adjustments

in order to refine the questionnaire.

Firstly, we updated the question’s order. We

changed the order of the questions in the dimension

KMP following the KM expert’s suggestion

facilitating the understanding of the questions once it

begins from the specific to the general theme. Also,

the question 2.5 in the OKI dimension was moved to

dimension OKSH once that question was related to

knowledge dissemination (see Appendix).

Secondly, we removed some questions. Based on

our analysis, we decided to remove from the

questionnaire three questions as follows. The

question 2.4 from dimension OKI once it was

similar to the question 2.8 of the same dimension.

Also, we removed the question 2.2 from dimension

OKI because it was similar to question 4.2, the

dimension OKR (see Appendix).

Thirdly, we added two new questions in the

dimension KMPT. The questions enable the

participant informs other practices and tools adopted

by the organization and also not listed in that

dimension. Thus, the question added is ‘Could you

inform other practices/tools which your team use

daily and are not listed above?’ (see Appendix).

Finally, we decided do not unify the dimensions

OKST and OKSH once they have different

objectives, as observed by the KM expert.

Moreover, while KM requires a holistic view, we

also decided not to change the term ‘organization’

by different terms as suggested one of the

participants.

Therefore, the results achieved here show that

the questionnaire is relevant and adequate for the

SME-Soft. The participants highlighted that the

questionnaire helps them to understand KM

processes, practices, and tools within SME-Soft,

getting some insights to carry on KM with their team

within the organization.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This research carried out a POC to refine and

validate a questionnaire addressed to investigate KM

processes, practices, and tools in SME-Soft. As

results, the participants suggested some improve

points in which we analyzed and accepted several of

them. Curiously, we also find out that while the

participants were assessing the questionnaire, they

had some insights regarding KM processes and

practices performed by their organization. In

addition, the strength of the questionnaire was the

answer time. Moreover, all the participants

considered the questionnaire very relevant to

investigate KM within SME-Soft. However, one

limitation of this work was the lack of conducting

interviews with participants. For the future work, we

intend to broaden our sampling and also conduct

mixed methods performing interviews with KM

experts and practitioners and with software industry

workers aiming to refine further our questionnaire.

Investigating Knowledge Management in the Software Industry: The Proof of Concept’s Findings of a Questionnaire Addressed to Small

and Medium-sized Companies

79

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our special thanks to Cesumar Institute of Science,

Technology, and Innovation (ICETI - Instituto

Cesumar de Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação),

Maringá, Paraná, Brazil. We also thanks to

Programa de Suporte a Pós-Graduação de

Instituições de Ensino Particulares (PROSUP) of

Coordination for the Improvement of Higher

Education Personnel (CAPES - Coordenação de

Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior),

Brazil.

REFERENCES

Aaker, D. A., Kumar, V., Day, G. (2001). Marketing

Research. John Wiley & Sons.

Andreeva, T., Kianto, A. (2011). Knowledge processes,

knowledge intensity and innovation: a moderated

mediation analysis. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 15(6), 1016–1034.

Aurum, A., Daneshgar, F., Ward, J. (2008). Investigating

Knowledge Management practices in software

development organisations - an Australian experience.

Information and Software Technology, 50(6), 511–533.

APO. (2009). Knowledge management: facilitator’s guide.

Retrieved from <http://www.apo-tokyo.org/00e-

books/IS-39_APO-KM-FG.htm>

Bjornson, F. O., Dingsoyr, T. (2008). Knowledge

management in software engineering: a systematic

review of studied concepts, findings and research

methods used. Information and Software Technology,

50(11), 1055–1068.

Bukowitz, W. R., Willians, R. L. (1999). The knowledge

management fieldbook. London: Pearson Education

Limited.

Capaldo, A., Petruzzelli, A. M. (2015). Origins of

knowledge and innovation in R&D alliances: a

contingency approach. Technology Analysis and

Strategic Management, 27(4), 461–483.

Chang, C. L., Lin, T. C. (2015). The Role of

Organizational Culture in the Knowledge Management

Process. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(3),

433–455.

Choo, C. W. (2006). The knowing organization as

learning organization. Education + Training 2nd ed.,

Vol. 43. New York: Oxford University Press.

Colomo-Palacios R., Fernandes E., Soto-Acosta P.,

Larrucea, X. (2018). A case analysis of enabling

continuous software deployment through knowledge

management. International Journal of Information

Management. 40, 186-189.

Dalkir, K. (2011). Knowledge Management in Theory and

Practice. 2 ed. Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Davenport, T. H., Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge:

how organizations manage what they know. Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Del Giudice, M., Maggioni, V. (2014). Managerial

practices and operative directions of knowledge mana-

gement within inter-firm networks: a global view.

Journal of Knowledge Management, 18(5), 841–846.

Demchig, B. (2015). Knowledge Management Capability

Level Assessment of the Higher Education

Institutions: Case Study from Mongolia. Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 3633–3640.

Fonseca, A. F. (2006). Organizational knowledge

assessment methodology. Washington: Word Bank

Institute.

Freeze, R., Kulkarni, U. (2005). Knowledge Management

Capability Assessment: Validating a Knowledge

Assets Measurement Instrument. Proceedings of the

38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on

System Sciences, 0(C), 1–10.

Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in Organizations: a

conceptual framework. Human Resource Development

Review, 2(4), 337–359.

Kendig, C. E. (2016). What is Proof of Concept Research

and how does it Generate Epistemic and Ethical

Categories for Future Scientific Practice? Science and

Engineering Ethics, 22(3), 735–753.

Khatibian, N., Hasan, T., Jafari, H. A. (2010).

Measurement of knowledge management maturity

level within organizations Measurement of knowledge

management maturity level within organizations.

Business Strategy Series Business Process

Management Journal Iss Journal of Knowledge

Management, 11(6), 793–808.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of

attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 5–55.

Muthuveloo, R., Shanmugam, N., Teoh, A. P. (2017). The

impact of tacit knowledge management on

organizational performance: Evidence from Malaysia.

Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(4), 192–201.

Nair, P.; Prakash, K. (2009). Knowledge management:

Facilitator's guide. APO: Tokyo.

Nawinna, D. P. (2011). A model of knowledge

management: delivering competitive advantage to

small & medium Scale Software Industry in Sri Lanka.

6th Internacional Conference on Industrial and

Information Systems, 414–419.

Neuendorf, K.A. (2016). The content analysis guidebook.

Sage.

Oliva, F. L. (2014). Knowledge management barriers,

practices and maturity model. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 18(6).

Perez-Aros, A., Barber, K. D., Munive-Hernandez, J. E.,

Eldrige, S. (2007). Designing a knowledge

management tool to support knowledge sharing

networks. Journal of Manufacturing Technology

Management, 18(2), 153–168.

Pinto, D., Bortolozzi, F., Menegassi, C. H. M., Pegino, P.

M. F, Tenório, N. (2016). Design das etapas a serem

seguidas em um instrumento para a coleta de dados

para organizações do setor de TI. In: VI Congresso

Internacional de Conhecimento e Inovação – CIKI.

Serna, E., Bachiller, O., Serna, A. (2017). Knowledge

meaning and management in requirements

KMIS 2018 - 10th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

80

engineering. International Journal of Information

Management, 37, 155–161.

Siadat, S. H., Kalantari, H., Shafahi, S. (2016). Assessing

knowledge management maturity level based on APO

approach (a case study in Iran). International Journal

of Social Science and Humanities Research, 4(3),

629–638.

Vestal, W. (2002). Measuring Knowledge Management,

APQC (American Productivity & Quality Center,

Houston, TX.

Wiig, K. (1993). Knowledge management foundations.

Arlington, TX: Schema Press.

Wee, J. C. N., Chua, A. Y. K. (2013). The peculiarities of

knowledge management processes in SMEs: the case

of Singapore. Journal of Knowledge Management,

17(6), 958–972.

Yagüe, A., Garbajosa, J., Díaz, J., González, E. (2016). An

exploratory study in communication in Agile Global

Software Development. Computer Standards and

Interfaces, 48, 184–197.

Zhang, X., Jiang, J. Y. (2015). With whom shall I share

my knowledge? A recipient perspective of knowledge

sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(2),

277–295.

APPENDIX

KM Questionnaire to SME-Soft

KM Perception Dimension (KMP)

1.1 Have you heard about knowledge management

in any lecture, course, meeting, or conference? Y/N

1.2 Do you know what knowledge management is?

Y/N

1.3 Is knowledge management currently a topic of

interest to the organization? Y/N

1.4 Does the organization understand that

knowledge is a resource of the organization? Y/N

1.5 Is it fact that knowledge is stored in people? Y/N

1.6 Does conduct knowledge management practices

by the organization? Y/N

If the answer is YES

1.6.1 How long are knowledge management

practices in the organization?

1.6.2 Are all areas aware of the organization's

knowledge management practices? Y/N

1.6.3 Are knowledge management practices carried

out in all areas of the organization? Y/N

1.6.4 Does the organization have a defined vision

or justification for the practice of knowledge

management? Y/N

1.6.5 Knowledge management is aligned with and

is part of the organization's management model?Y/N

1.6.6 Does the organization continually and

systematically assess knowledge management

practices, identify weaknesses, and define and use

methods to eliminate them? Y/N

If the answer is NO:

1.6.7 Do you know if there are plans to implement

projects on knowledge management in the

organization? Y/N

1.6.8 How soon will the project be implemented?

Organizational Knowledge Identification Dimension

(OKI)

2.1 How often do employees often turn to colleagues

within the organization to solve problems?

Always/Frequently/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

* 2.2 How often do employees use other sources of

knowledge (intranet, internet, database, manuals) to

solve their problems?

Always/Frequently/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

2.3 Employees know “who knows what” within the

organization, making it clear where to look for

specific information? Y/N

* 2.4 What resources do employees use to obtain

information?

● 2.5 Do all employees express their ideas?

Always/Frequently/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

2.6 Are employees’ ideas taken into account for the

organization’s decision-making?

Always/Frequently/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

2.7 Is the involvement of customers in the process of

creating and developing new products and services a

well-established practice in the organization?

Always/Frequently/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

2.8 How does the organization disseminate

information or knowledge to its employees?

Organizational Knowledge Storage Dimension

(OKST)

3.1 What resources does the organization use to

store knowledge?

3.2 Knowledge storage media is updated:

Always/Frequently/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

3.3 Does the knowledge storage space in the

organization have a structure that enables everyone

to contribute? Y/N

3.4 Is the knowledge stored in the organization

intended for all sectors of the organization? Y/N

Organizational Knowledge Recovery Dimension

(OKR)

4.1 When people are given the task of researching

information in the organization, are they able to do

it? Always/Frequently/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

4.2 Where do people usually look for information on

the company?

Investigating Knowledge Management in the Software Industry: The Proof of Concept’s Findings of a Questionnaire Addressed to Small

and Medium-sized Companies

81

Organizational Knowledge Sharing Dimension

(OKSH)

5.1 Does the organization motivate its employees to

share information with each other? Y/N

5.2 Do all employees in the organization share

information with each other? Y/N

5.3 Is the workspace designed to promote the flow

of ideas between workgroups? Y/N

5.4 Are people afraid to share their knowledge with

other colleagues in the organization? Y/N

5.5 Does the organization support group activities?

Y/N

† 5.6 (previously 2.5) Do all employees express their

ideas? Always/Frequently/Sometimes/Rarely/Never

KM Practices and Tools Dimension (KMPT)

‡ KM Practices

Knowledge coffee (1/2/3/4/5)

Communities of practice (1/2/3/4/5)

Knowledge map (1/2/3/4/5)

Mentoring (1/2/3/4/5)

Brainstorming (1/2/3/4/5)

Capturing ideas (1/2/3/4/5)

Adoption of best practice (1/2/3/4/5)

Peer Assist (1/2/3/4/5)

Peer Review (1/2/3/4/5)

Storytelling (1/2/3/4/5)

Coaching (1/2/3/4/5)

Internal Benchmarking (1/2/3/4/5)

External Benchmarking (1/2/3/4/5)

Meetings (1/2/3/4/5)

Competency management system (1/2/3/4/5)

Bank of individual skills (1/2/3/4/5)

Technical improvement courses (1/2/3/4/5)

Lectures, training and workshops (1/2/3/4/5)

Balanced Scorecard (1/2/3/4/5)

Reporting (1/2/3/4/5)

∆ Could you inform other practices which your team

use daily and are not listed above?

‡ KM Tools

Database (1/2/3/4/5)

Noticeboard (1/2/3/4/5)

Virtual bulletin board (1/2/3/4/5)

Virtual collaboration spaces (1/2/3/4/5)

E-mail (1/2/3/4/5)

Blogs (1/2/3/4/5)

Chat (1/2/3/4/5)

Video (1/2/3/4/5)

Text (1/2/3/4/5)

WhatsApp (1/2/3/4/5)

Skype (1/2/3/4/5)

Facebook Messenger (1/2/3/4/5)

Virtual forums or discussion lists (1/2/3/4/5)

Intranet (1/2/3/4/5)

Official documents (1/2/3/4/5)

Handbooks (1/2/3/4/5)

Reports (1/2/3/4/5)

Kanban (1/2/3/4/5)

Canvas (1/2/3/4/5)

∆ Could you inform other tools which your team use

daily and are not listed above?

* Questions removed (strikethrough).

∆ Questions added.

● Questions moved to another dimension.

† Questions coming from another dimension.

‡ Likert Scale: (1) Strongly disagree; (2) Disagree;

(3) Neither agree nor disagree; (4) Agree; (5)

Strongly agree

KMIS 2018 - 10th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

82