Reconnecting with Past and Present

Personalizing Sensory Stimulated Reminiscence Through Immersive Technologies

– Developing a Multidisciplinary Perspective on the SENSE-GARDEN Room

Jon Sørgaard

1

, Mihai Berteanu

2

and J. Artur Serrano

1,3

1

Department of Neuromedicine and Movement Science, Faculty of Medicine and Health,

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

2

University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, Bucharest, ELIAS University Hospital, Romania

3

Norwegian Centre for eHealth Research, University Hospital of North, Norway

Keywords: Dementia, Sociotechnical Network, Sensory Stimulation, SENSE-GARDEN, Immersive Technology,

Personalization, Active and Assisted Living, Welfare Technology, Assistive Technology, Emotion

Quantification, Actor Network Theory.

Abstract: Dementia is a degenerative disease affecting the cognitive abilities in a serious way among the persons living

with it. Through different kinds of sensory stimulation, one may slow down the deterioration processes among

persons with dementia. The use of personal photographs, storytelling and familiar question-and-answers in

an informal setting and with informal caregivers may be very valuable. Several national health services around

the world have established sensory stimulation gardens (sense-gardens), as well as sensory stimulation rooms

(Snoezelen rooms). In the SENSE-GARDEN room, we build on these concepts to develop and implement

immersive technologies that create multisensory stimulation – sound, sights, smells, movements. We propose

technology-based tools that link the stimulation experience directly to the personal history of persons with

dementia to help them reconnect with their past and present. The professional participants in the project come

from different fields and have different expectations and views on the various aspects of the project. This may

have affect on elements such as goals, strategies, and tasks. In this paper, we sum up our work to build a

common understanding and definition of these elements. By using a qualitative approach, we have mapped

the different perspectives among representatives of the professional groups involved in the SENSE-GARDEN

room. The methods used for mapping and analysing these differences are described. We have discovered

some a priori differences that mainly seem to be related to the professional groups. To some extent, this may

be due to each group’s tasks and responsibilities within the project, but most likely also to different

professional cultures. However, through the process we have found a strong commitment to define a common

ground from where the project can progress. The differences we are left with are complementary, not

contradictory, and will be valuable as they allow to shape synergies within the development of various aspects

of the project.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 The Challenge

One of the main characteristics of dementia is the

deterioration of memory capabilities. This represents

practical challenges in everyday life for diagnosed

individuals, with capabilities in remembering how to

perform daily activities becoming progressively

impaired.

The ability to perform these activities on an

efficient level is a prerequisite for an independent life.

When the ability to do so is restricted the person’s

independence will also gradually be reduced. (Holthe

et al., 2017, Dooley and Hinojosa, 2004))

Dementia is a serious problem, both on a personal

and on a societal level. On an individual level, it

affects the ability to take an active part in one’s own

personal life (Nguyen et al., 2017). For society, it

places pressure on resources, both on human

resources within the health services, and on economic

resources. The demographic changes in Europe most

likely implicate that the prevalence of dementia will

grow in the years to come. Both on personal and

234

Sørgaard, J., Berteanu, M. and Serrano, J.

Reconnecting with Past and Present.

DOI: 10.5220/0006792302340240

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2018), pages 234-240

ISBN: 978-989-758-299-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

societal levels every serious effort to meet these

challenges should be regarded as important

contributions.

Our lives are lived in a complex context. Our

reality is not purely social or cultural, nor material or

biological. Our health issues relates to social

relations, genetics, biology, chemistry, psychology,

economy, climate, and more.

One might say that technology is the link in this

complex weave: All technology – ideally, and in its

core – is designed to help people meeting different

challenges. This may be done through extending,

strengthen or improving the individual’s capacities

and competences, by replacing or compensate for

capacities that are not present, available, or sufficient,

or by reducing the effects of unwanted individual

characteristics.

We want to explore whether – and how - we

through careful use of different technologies within a

SENSE-GARDEN room may be able to stimulate the

memory capacities among persons with dementia so

that they more easily may reconnect with their own

lives. If this is shown to be the case, one might expect

significant positive effects on life quality, social

participation and communication with others.

1.2 Project’s Aim

Several health organizations and national health

services around the world – for instance in Canada,

Denmark, Germany, Norway, Sweden, UK, and

many more - have established sensory stimulation

gardens (sense-gardens), as well as sensory

stimulation rooms (Snoezelen rooms) (Cox et al.,

2004, Berentsen et al., 2007). Most of the sensory

stimulation gardens, however, have been gardens in a

horticultural sense.

Systematic use of different stimuli has of course

been used extensively through the years, and has a

central place in dementia care. This goes for both

photographs (Yasuda et al., 2009), videos (Capstick

and Ludwin, 2017), music (Onieva-Zafra et al.,

2018). However, the potential in the various

technologies has not yet been fully exploited (Bejan

et al., 2018; Lorentz et al., 2017, Lazar et al., 2014;

Westphal et al., 2010).

The SENSE-GARDEN room proposes an

innovative approach to the care of individuals living

with dementia. Within the project, we will develop a

therapeutic environment through blending

technology together with architectural, social,

emotional, and physical elements. Through this, we

will provide a platform and means for creating

individually adjustable visual and sound stimuli, as

well as stimuli for tactile and olfactory senses.

In the SENSE-GARDEN room, we build on these

concepts, but take it further by creating a mixture of

natural and technological environments, which are

linked to the individual memories of the user, and

automatically adapt to them. To actually design a

technical solutions with the ability to adapt

automatically to the users’ individual preferences and

capacities is one of the ambitious aims of the project,

and one that calls for a creative and ground-breaking

multidisciplinary approach.

SENSE-GARDEN rooms are filled with familiar

music, videos and photos from known places and with

known people. Pictures and videos are combined with

music – such as a large image of mountains together

with singing birds, for example. Smells - for example,

the odour of a pine forest - are dispersed with a scent

delivery system. This provides an immersive space

that is automatically adjusted to each visitor, the

person with dementia, creating a connection to the

more active areas of the memory. Relatives will have

a key role in providing information regarding the

users’ past life.

By stimulating the senses, we hope to create

reminiscence activity in the minds of persons with

dementia, which may help them to reconnect with

reality – both with their own personal history and with

the present moment. The underlying idea is that this

will benefit not only the persons with dementia, but

also their close and loved ones, as well as the health

services (Macdonald et al., 2017). Most of all, our

ambition is to improve quality of life and sense of

wellbeing among the persons with dementia.

1.3 The Task at Hand

The project includes public and private partners in

Belgium, Norway, Portugal, and Romania. Its

multidisciplinary team comprises elements from a

wide range of professional activities such as care-

giving, medical aid, technical, law, architecture,

business, research, etc. With this wide range of

competencies, there also comes a wide range of

perspectives on what should be achieved, what may

be achieved – and how to achieve it.

The most important questions in establishing a

common ground for the development of the

technological solutions, including the technological

framework, are the familiar what, how, and who.

What is this project really about? What should be

the outcome? What are the key success factors? What

is needed to achieve the – hopefully – common goals?

Reconnecting with Past and Present

235

What is the new vision we can bring into the treatment

of dementia?

How can a technical framework be of help to the

persons with dementia and their caregivers? How

shall we define and develop the right technological

solutions? How can the solutions proposed be turned

into real innovations? How can we be sure that all

relevant competences and groups – engineers,

designers, health professionals, architects,

economists, informal caregivers – are represented and

their competences used within the project? And how

can we ensure that the voice of the persons with

dementia are integrated in the project?

Then the ‘whos’: Who defines which technology

is needed? Who defines which technology is the best?

Who does what in the project? Who defines what is

needed throughout the different stages?

And maybe more important than any other

question: How can we be sure that our achievements

actually will benefit persons with dementia?

The project is carried out by a wide range of

professionals, within medicine, health sciences, care,

architecture, technology, economy and

administration, social science and more. Most

important, we have been able to open up a discussion

by ‘exploiting’ the different professional approaches.

In this paper we describe how the basic ideas in the

project has been established as a collective property

within the project group. To create this kind of

common platform we have conceived as important

especially with reference to the multiprofessional

background among the participants. From this

platform, we also will describe the initial stages of the

project so far.

2 THEORY AND CONCEPTS

2.1 Artefacts – and More

One should notice that our point-of-departure is a

relatively broad understanding of the term

‘technology’. Any given technical artefact is part of

what may be called a sociotechnical network (cf. 1.3)

(Bijker and Pinch, 1987).

Within STS studies (Science, Technology and

Society) the term sociotechnical network is used to

describe technological artefacts within their relevant

context, a context that can be viewed upon as a

heterogeneous network where humans and non-

humans are mixed together in a dynamic co-play

(Latour, 1992).

This leads to the notion that one needs to take both

technical and social elements into consideration to

fully understand technology, why it may or not may

function in a proper way, and therefore also the

prerequisites for technical development. These

‘additional elements’ are ‘everyone and everything’;

they may be human actors such as designers and

constructors, users on different levels and different

users’ competences, other artefacts, necessary

knowledge and skills, a variety of stakeholders, and

so on.

In our case – the immersive sense-garden – the

architecture, the different sensors and devices for

distributing stimuli, computers that control the

system, formal and informal caregivers, technical aid

and support, health authorities, the users’ needs and

competencies and more must all be brought together

in a functioning collaboration to make the technology

work.

This is what we have tried to take into account

when we organised a seminar with the project team

defining an early challenge to create a common

ground. This process is described in the Method

section.

2.2 Script and Program

Actor Network Theory, influenced by semiotic

analysis, points out that any artefact can be said to

contain a script. The artefact can be viewed as a form

of text, and through narrative analysis, this text can be

read. Through this narrative analysis one can extract

the meaning and so it may be ‘de-scripted’ (Akrich,

1992).

The script tells us about the designer’s/

constructor’s intentions with the technology, his or

her visions of what it can do, and how it should be

used. This can be interpreted as guidelines for how

the technology should be used – a program.

This des-cription, this reading of the technology,

this identifying of a program, is not something that

we do in our everyday life. Still, on an unconscious

level, maybe this is what we do after all: Facing a

given technology we interpret what it can do for us,

what we have to do in order for it to do what we like,

and what we need to achieve this. We will find

ourselves facing three options:

- We may accept the program – in the way that we

can and will use it according to the designer’s

intention, to achieve what we are told that we can

achieve (i.e. subscribing to the program)

- We may reject the program, by just refusing to use

the technology, or by being prevented from using

it, not able to meet the demand of necessary

resources and competencies

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

236

- We may reject the program as it is presented to us,

but by redefining the program and/or reshaping

the technology we may use it for another purpose

or in another way according to our own needs,

goals, and capabilities (i.e. creating an anti-

program).

Why is this important for our project? As we want to

create and implement technology that will prove to be

to the end-users’ benefit, we need to establish a good

relationship between all relevant social groups within

the sociotechnical network (Bijker and Pinch, 1987).

3 METHODS AND TECHNIQUES

3.1 Reflections upon Methodology

Throughout the project, we will apply a variety of

methods, both in order to gather and analyse data

needed for the development/construction process, and

also for the analysis of effects and outcomes of the

technology we implement.

Both qualitative and quantitative data is needed.

To gather these data we will include tools such as

surveys/questionnaires, different measuring devices,

demographic and economic statistics, observations,

semi-structured interviews, and through sessions of

group interviews and discussions. During the project,

we will gather interview data from all relevant groups

within the project as well as with end-users, informal

caregivers and professionals within formal health

care not participating directly in the project.

Likewise, the analysis of these data obviously has

to span over a wide range of analytical tools – from

statistics to narrative analysis.

The overall methodological framework may be

described as action research: We are introducing

certain stimuli during the project. Not only as stimuli

as part of the SENSE-GARDEN experience in itself,

but also by introducing a new service within health

care. The project aims to have an effect and an

influence on the field studied, and as the project

moves forward the object of our study will change,

partly due to our interventions.

In the same way, since we are studying the

processes as they take place, the development of the

project, and the changes within it, will affect our

study. The development and implementation of

technology, the reconstruction of the social and

sociotechnical setting, and the research project should

be seen as interdependent, and as constantly

influencing each other. From a research point of view,

this means that the research design will have to

change during the project – not only by taking into

account the changes that occur in what we study, but

also by considering how the research itself may affect

what is going on in the project. (Creswell, 2007)

3.2 ‘The Yellow Sticker Approach’;

Finding a Common Ground

We now describe an initial qualitative study

performed with the aim to build a common

understanding between the project members. For our

purpose, the qualitative approach has two main

advantages: Firstly, qualitative methods are well

suited to map attitudes and values so that one can get

a broad picture of the actual variations in the field

studied. Secondly, a qualitative approach may open,

as we saw above, possibilities to initiate changes

throughout the process. Whether this is the case

depends on which method one has chosen.

The methodology we chose included a group

session with the various professionals represented in

the project team. The method was organized in two

stages.

Initially we collected information using yellow

stickers on the participants’ views on certain aspects

of the SENSE-GARDEN room, its basic concepts and

strategies. This was done on an individual level, and

provided us with information on the thoughts and

ideas that each participant was bringing into the

project. This stage may be described as a process of

opening up the width in perspectives.

In the second stage, the group discussed the

content from the yellow stickers. The individual

perspectives were processed collectively, and this

stage may be described as consensus-seeking.

4 THE FINDINGS; VARIATIONS

AND ESSENCE

4.1 Findings

An initial analysis of the yellow stickers show that

different views may be identified and classified:

usefulness, ethical judgement, feasibility.

Through our analysis, we could see that the

participants – quite loosely – clustered into three

groups or personas: 1) formal caregivers and other

staff from social care institutions, 2) representatives

of specialised medical services and medical doctors,

and 3) researchers/technologists/designers. This is

reflected also through an underlying view on the

relation between the user and the project itself.

Reconnecting with Past and Present

237

4.1.1 Variations

As we went through the keywords that were given on

the yellow stickers, we saw that they could be seen as

positions along a continuum from ‘the active’ patient

to ‘the passive’ patient. Many of the keywords

referred specifically to what the project can ‘deliver’:

‘Help’, ‘give support’, ‘provide better health’ –

implicating that the project itself can be seen as a

provider and the person with dementia as the

recipient.

On the other hand, we found keywords on how the

project may affect the patients so that they can be

active participants in improving their lives. These

keywords contained, for example, terms such

‘empower’ and ‘stimulate’, terms which imply that a

central goal within the project is to support and

encourage the user to be a more active participant, to

provide them with opportunities to use their own

resources to improve wellbeing and life quality – to

be an active patient.

It should be noted that these differences were

more of a complementary character rather than

contradictory, but still with some different notions of

the relation between the project and the patient.

We understand this mostly as an effect of the

different tasks these groups are expected to take care

of in society. The medical doctors, for instance,

possess some highly specialised competences – these

are primarily meant to be used on behalf of or in the

service of the sick person, rather than to be spread to

and adopted by the patient. For the professional

caregivers, the interaction with the patient and his/her

primary network is essential – to establish a close,

although not private, relation with the person that is

in need of care. Finally, technology developers and

designers focus on creating something for the user.

Doing so, they know that one needs to take the user’s

perspective into account, to be sure that the solutions

will work for him or her.

4.1.2 The Essence

The process led to identifying common keywords:

“emotions”; “reconnected”; “their social

relations/their life”. In the end a common essence, an

expression capturing the goal of the project with a

consensual agreement, was achieved: “Emotions

reconnect us”. We therefore could see how the

professional groups were able to define a common

ground, instead of letting unnecessary controversies

dominate the collaboration throughout the project

period.

The arrival on a common platform grew out from the

group

discussions. Through the discussions, the

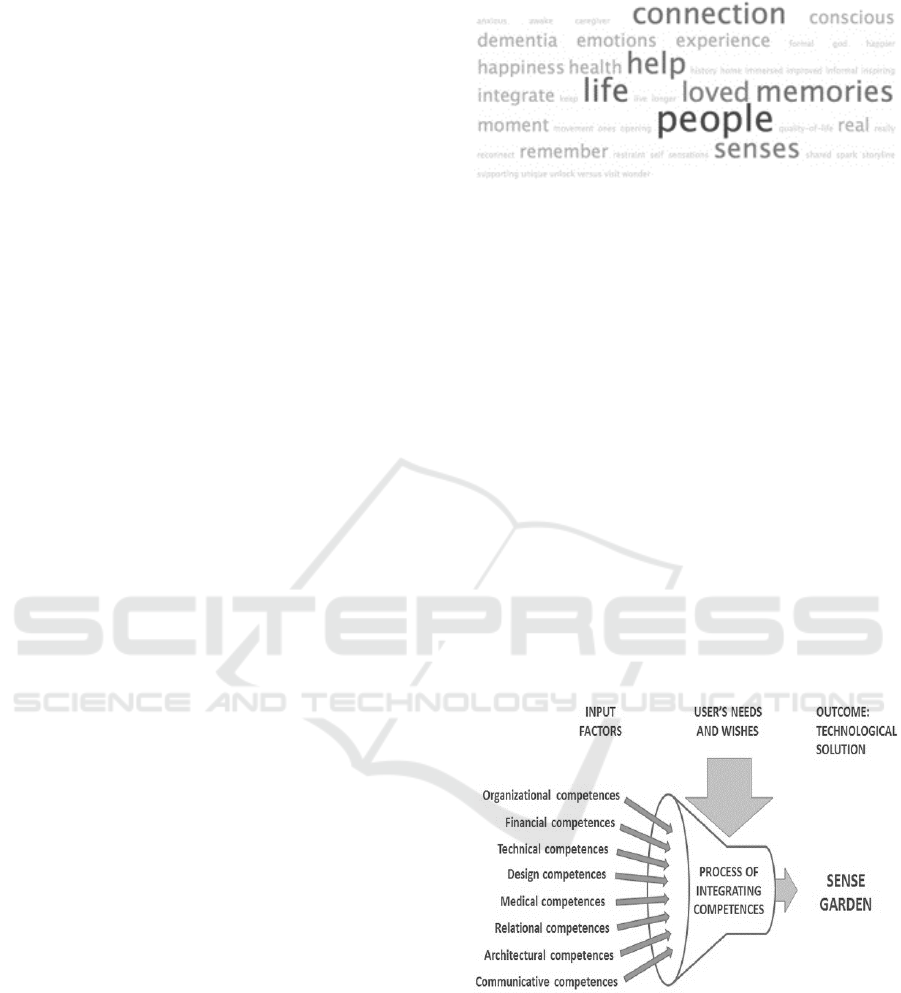

Figure 1: Word-cloud extracted from the brainstorming.

various views and ideas were presented and

elaborated, for then to be validated by the group. In

this way we achieved two things: We became able to

construct a common understanding, and achieved a

kind of collective ownership to the final findings and

conclusions.

4.1.3 Sociotechnical Networks

Through our analysis, we confirmed that the

perspective of sociotechnical networks, with the

conception of how different artefacts and social

elements together form a functional technical

solution, seems very fruitful. This was an overall

understanding among the professionals, however

different their basic tasks and views were. The

concept highlights the importance of bringing

together all the relevant social groups within the

network so that they may be able to reach a common

understanding.

Figure 2: Translating different competences into one

unified solution (inspired by Latour, 1988).

The process of reaching a common understanding

can, with reference to Actor Network Theory, be

described as a process of negotiation and translation

(Bijker and Law, 1992). Different competences and

basic views from the different professionals are

negotiated between the participants, and translated

accordingly to fit into an emerging common platform.

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

238

The overall ‘negotiation guideline’ is the

reference to the user’s perspective. How the

competences are to be translated to form the basis for

the further work has to take this into account. In the

end, the critical factor for evaluating a given technical

solution is whether it will function for the user within

his or her context.

5 DISCUSSION

The project challenges the way we look at dementia –

an innovative view on dementia treatment, one that

engages the patient and reconnects her or him to

reality. In the SENSE-GARDEN room, we will

develop and implement immersive technologies that

create multisensory stimulation – sound, sights,

smells, movements. By doing so, we go from

standardized designs to personalized solutions. By

linking the stimulatory experience directly to the

person’s own history, we may have an even stronger

tool for helping persons with dementia to reconnect

with their past – and through this their present life as

well: Activities, values, family, loved ones, etc.

In projects like this, the different groups of

participants will typically have somewhat differing

expectations and views on the foundation of the

project. This will affect perspectives on elements

such as goals, strategies, and tasks. To achieve

success in the project, it is necessary to reach a

common understanding of its basic concepts. We

have attempted at building a common understanding

and definition of these elements. By using a

qualitative approach, we have mapped the different

perspectives among representatives of the

professional groups involved in the SENSE-

GARDEN room. In this process, we have discovered

some a priori differences that mainly seem to be

related to the professional groups. To some extent,

this may be due to each group’s tasks and

responsibilities within the project, but most likely

also to different professional cultures.

The user-perspective is crucial when developing

and shaping technology in general, but even more so

when it is a strong emphasis on personalization or

individualization of the technical solutions. You can’t

personalize without knowledge about, and from, the

persons in focus.

6 ACHIEVEMENTS AND

FURTHER WORK

What has been achieved? Within the project we have

developed a common understanding, but still

managed to take care of the complementary

differences between the participants. In this respect,

we have a very good platform for our further work.

Users and informal caregivers have been included

in the project, and 50 interviews have been carried

out. This number will be extended, and we will follow

the user’s experiences with the SENSE-GARDENs as

they unfold. This will be important data, and

supplemented with other types of information as well.

This variety of datatypes will help us to continuously

develop the project further.

We have developed and built the first virtual

SENSE-GARDEN prototype in Belgium. More are in

progress, and will be taken into use as they are

completed.

As mentioned above we have an ambitious project

with respect to develop a method for individualized

stimulation of senses, where possibilities for this is

built directly into the technology. To further develop

these solutions are the main task in the further

progress of the project.

We have also an ambitious task with reference to

how we shall measure the outcomes of this project.

This is a challenge not only in our project but in most

projects dealing with health, well-being and quality

of life. To further develop these methods of

measuring are therefore also an important tasks to be

addressed. It seems clear that no single datatype or no

single research method will be sufficient to provide a

full picture of the knowledge generated in the project.

To develop and implement welfare or assistive

technology is a truly multidisciplinary task. It

depends on a wide range of professionals with

different backgrounds, and therefore different

perspectives and expectations. However, these

differences are more of a complementary character

rather than contradictory, and can help in the creative

process. In the SENSE-GARDEN the fundament of

the work is not only to develop the technical

solutions, but also to lay the foundation for the

technology to be taken into use.

In addition to the professionals directly involved

in the project, there is a vital necessity to establish a

close collaboration with both the persons with

dementia and their informal caregivers. This process

is known as users’ co-design, and is also being used

in SENSE-GARDEN. This will be the focus of

another paper. Inclusion of the users’ perspective is

essential to ensure that the outcome of the project will

Reconnecting with Past and Present

239

actually benefit them. In the end, it is the users that

may define the outcome as a success or not –

depending on whether the solutions can and will be

used, and whether they actually improve the users’

sense of wellbeing, their reconnection with and

participation in their own lives, and their quality of

life.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank David Ashford Jones, CEO

of Sagio Ltd., for facilitating the brainstorming

process.

REFERENCES

Akrich, M., 1992. The De-scription of Technical Objects.

In Bijker, W.E and Law, J. (eds.). Shaping Technology/

Building Society. Studies in Sociotechnical Change,

Bejan, A., Gündogdu, R., Butz, K., Müller, N., Kunze, C.,

König, P., 2018. Using multimedia information and

communication technology (ICT) to provide added

value to reminiscence therapy for people with

dementia: Lessons learned from three field studies.

Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 51(1), pp. 9-

15.

Berentsen, V.D., Grefsrød, E., Eek, A., 2007. Sansehager

for personer med demens. Forlaget Aldring og helse,

Tønsberg, Norway

Bijker, W.B., Pinch, T., 1987. The Social Construction of

Facts and Artifacts: Or How the Sociology of Science

and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each

Other, in Bijker, W.B., Hughes, T.P., Pinch, T. (eds.)

The Social Construction of Technological Systems

Bijker, W.B., Hughes, T.P., Pinch, T., (eds.), 1987. The

Social Construction of Technological Systems, The

MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., USA/London, England

Bijker, W.E. and Law, J., (eds.) 1992. Shaping Technology/

Building Society. Studies in Sociotechnical Change.

The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., USA/London,

England

Capstick, A., Ludwin, K., 2014. Place memory and

dementia: Findings from participatory film-making in

long-term social care. Health and Place, 34, pp. 157-63

Cox, H., Burns, I., Savage, S., 2004. Multisensory

environments for leisure: promoting well-being in

nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of

Gerontological Nursing, vol.30(2)

Creswell, JW (2007) Qualitative Inquiry & Research

Design

Dooley, NR. and Hinojosa J., 2004. Improving quality of

life for persons with Alzheimer's disease and their

family caregivers: brief occupational therapy

intervention. American Journal of Occupational

Therapy, vol.58 (5)

Holthe, T., Jentoft, R., Arntzen, C., Thorsen, K., 2017.

Benefits and burdens: family caregivers' experiences of

assistive technology (AT) in everyday life with persons

with young-onset dementia (YOD). Disability and

Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, vol.11

Latour, B., 1988. Science in Action. How to Follow

Scientists and Engineers through Society, Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, Mass., USA

Latour, B., 1992. Where Are the Missing Masses? The

Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts. In Bijker, W.E.

and Law, J., (eds.) Shaping Technology/ Building

Society. Studies in Sociotechnical Change.

Lazar, A., Thompson, H., Demiris, G., 2014. A systematic

review of the use of technology for reminiscence

therapy. Health Education & Behaviour, 41(1 Suppl),

pp. 51S-61S

Lorenz, K., Freddolino, PP., Comas-Herrera, A., Knapp,

M., Damant, J., 2017. Technology-based tools and

services for people with dementia and carers: Mapping

technology onto the dementia care pathway. Dementia

(London). Available at https://doi.org/10.1177/

1471301217691617 (February 8, 2017)

Macdonald, M., Martin-Misener, R.,Helwig, M., Weeks,

L.,MacLean, H., 2017. Experiences of unpaid

family/friend caregivers of community-dwelling adults

with dementia: a systematic review protocol. JBI

database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation

Reports. 15(5)

Nguyen, M., Pachana, NA., Beattie, E., Fielding, E., Ramis,

MA., 2017. Effectiveness of interventions to improve

family-staff relationships in the care of people with

dementia in residential aged care: a systematic review

protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and

Implementation Reports, vol.13 (11)

Onieva-Zafra, MD., Hernández-Garcia, L., Gonzalez-Del-

Valle, MT., Parra-Fernández, ML, Fernandez-

Martinez, E., 2018. Music Intervention With

Reminiscence Therapy and Reality Orientation for

Elderly People With Alzheimer Disease Living in a

Nursing Home: A Pilot Study. Holistic Nursing

Practice, 32(1), pp. 43-50.

Westphal, A., Dingjan, P., Attoe, R., 2010. What can low

and high technologies do for late-life mental disorders?

Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23(6), pp. 510-5.

Yasuda, K., Kuwabara, K., Kuwahara, N., Abe, S.,

Tetsutani, N., 2009. Effectiveness of personalised

reminiscence photo videos for individuals with

dementia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 19(4),

pp. 603-19.

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

240