A Game of Wants and Needs

The Playful, User-centered Assessment of AAL Technology Acceptance

Eva-Maria Schomakers, Julia van Heek and Martina Ziefle

Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57, Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Ambient Assisted Living, Technology Acceptance, Qualitative User Study Approach, Age, Playful Approach.

Abstract: The use of Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) technologies presents one option to face the challenges of recent

and rising care needs due to demographic change. User acceptance of those technologies plays a major role

for a successful rollout and sustainable technology usage. Empirical research approaches (e.g., online

questionnaires) in this area are often impersonal and abstract for the participants. In contrast, the current study

aimed for a playful qualitative user study approach in which people empathize with different necessities of

support and evaluate desired technologies and respective usage motives as well as barriers. The paper presents

first research results of the new undertaken research approach, which was tested with six older participants

(aged between 50 and 81 years of age). The results show that the playful approach enables a personal

assessment of different assistive technologies and technology-related usage motives and barriers when a

prototype testing is not feasible.

1 INTRODUCTION

Demographic change causes high burdens for the care

sector as more and more older people are in need of

care (Walker & Maltby, 2012). As the majority of

older adults prefers to age in place and live

independently as long as possible (e.g., Wiles et al.,

2011), more and more technological solutions are

developed aiming for support and assistance of older

people and people in need of care in their everyday

lifes. The term, Ambient Assisted Living (AAL)

refers to the use of technologies to assist an older

person in aging-in-place, supporting living

independently, staying active, remaining socially

active and mobile (Blackman et al. 2016). Industry

and research institutions are currently working on

different types of AAL technologies as well as

holistic AAL systems. Prominent use cases are smart

home functions (e.g., sensors for control of lighting,

heating, doors, and windows) and the support of

communication with friends, family and caregivers,

fall detection, and other health care applications like

medication reminders.

The number of available AAL systems and

research projects is high (Memon et al., 2014).

Although these technologies have the potential to

facilitate everyday life and quality of life of older

adults, they are not yet widely used. One of the crucial

barriers against adoption of AAL technologies is the

technology acceptance of the potential users (Merkel,

2016).

Research on technology acceptance in various

contexts has been mostly dominated by the

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis et al.,

1989) and its derivatives. These models might explain

technology adoption sufficiently in a variety of

contexts. Regarding assistive technologies for older

adults, studies have shown that additional motives

and barriers play a significant role (e.g., Jaschinski &

Allouch, 2015, Peek et al., 2014). Potential users see

the advantages and necessity of assistive

technologies, but are at the same time concerned (e.g.,

regarding privacy violations, feelings of isolation).

Thus, it might not be sufficient to evaluate the ease of

using a system and the perceived usefulness, as

traditional models suggest. For the decision to use an

AAL system, the trade-off between the perceived

barriers and benefits in the individual context is

decisive (van Heek et al., 2017).

Much of the published research regarding

technology acceptance of AAL uses qualitative

methodologies like interviews and focus groups

(Peek et al., 2014). In these studies, the participants

typically evaluate one system that is described via a

presentation or scenario, or the participants can

interact with (a prototype of) that system. These

126

Schomakers, E., van Heek, J. and Ziefle, M.

A Game of Wants and Needs.

DOI: 10.5220/0006729901260133

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2018), pages 126-133

ISBN: 978-989-758-299-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

studies have identified a vast amount of motives and

barriers for older adults to use assistive technology.

Most prevailing barriers against AAL technologies

are general concerns regarding privacy intrusion, a

low usability of the system, and high purchase and

maintenance costs as well as the lack of perceived

benefits (Jaschinski & Allouch, 2015; Peek et al.,

2014). Perceived benefits include the increased

safety, independence, and the release of burden to

family and caregivers.

Wilkowska et al. (2015) conducted a comparison

of methodological approaches to measure privacy

concerns in an assistive environment. In a hands-on

experiment, the importance of privacy aspects

decreased in comparison to questionnaire studies and

focus groups. Thus, the method does considerably

influence the results and the evaluation of benefits

and barriers of a novel technology.

In this publication, we report a new qualitative

research approach. In a real-life situation, older adults

need not only choose whether to use a technology.

With more and more technologies on the market

(Merkel, 2016), they also have to choose between

different technology options (and non-technological

alternatives). Our hypothesis is, that confronting

participants with the choice between technology

options can reveal additional insights into older

adults’ decision-making processes, trade-offs, and

their evaluation criteria in choosing a technology. It

is a more realistic decision situation than evaluating

one system without knowing the technological

alternatives. Just like the differences in relative

importance between the questionnaire study, focus

groups, and hands-on-experiment in Wilkowska et al.

(2015)’s design, the importance of barriers and

benefits may shift with choice between technology

options. This is done in this study with a game-based

interview approach, in which details are visualized

and printed onto playing cards as a memory aid.

2 METHOD

The development of the method was led by the goal

to identify barriers and benefits of AAL technologies

that hinder usage in practice. Our hypothesis is, that

the reasons to (a) decide whether to use technology at

all for one use case differ from the reasons why (b) a

specific technology is chosen from alternatives. An

additional research question is, whether the criteria

for technology choice deviate between scenarios of

different necessity of support.

The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed

verbatim. The theoretical foundation of the analysis

was the qualitative content analysis by Mayring

(2010). Three coders viewed the whole material. The

study was carried out in German. For the publication,

selected quotes were translated to English.

Figure 1: Example of the interview procedure.

2.1 The Interview Procedure

After a short introduction, the interviews started with

questions about attitudes towards aging, the desire to

age in place, and attitudes towards technology (e.g.,

“What does quality of life mean to you?”, “Do you

like to be supported by technology in your everyday

life?”). The goal of these questions was to let the

interviewees put themselves into the situation of

aging and to relate to technologies that already

support their everyday life at present. Short questions

regarding prior knowledge of and experience with

AAL and smart home technologies followed.

In the main part (see Figure 1), two rounds of “the

game” were played, each round with the precondition

of a different scenario of the participant in older age.

The written and visualized scenario was laid on the

table as a memory aid. After introducing the scenario,

a first use case and the matching technology options

were explained (see Figure 2). To be more realistic

and to support memory, images of the technologies

were printed as playing cards with a description of the

technology’s characteristics on the back. The

participants were then questioned “Which of the

technologies would you prefer to use in the given

scenario?” and were asked to explain their reasoning

to the interviewer. A sketch of an apartment was

acting as the game board, to which the interviewees

could put those technologies that they wanted to use.

Additionally, the participants were asked to indicate

the most decisive reason for acceptance from nine

cards. This forced choice for one main benefit should

provoke a more active discussion about the reasons

for acceptance. In a second step, the interviewees

chose the most rejected technology in a similar

A Game of Wants and Needs

127

manner. This approach was repeated with each of the

six different use cases and their corresponding

technologies. The order of the use cases was

randomized between the interviews. As the scenarios

built on each other, their order was not changed.

After introducing the second scenario, the

participants were asked to depict potential changes in

technology choices as well as reasoning for

acceptance and rejection.

At the end of the interview, the participants were

asked to summarize their attitudes towards the

presented AAL technologies and to indicate motives

and barriers or conditions for acceptance that are most

important. After the interview, a short questionnaire

was applied assessing demographic data, experience

with ICT and AAL, as well as technical self-efficacy

(using an abridged scale by Beier (1999)).

2.1.1 The Scenarios

Two scenarios were presented to the participants. The

first scenario “moderate need for support” asks the

participants to imagine themselves as 71 years old,

living alone with small health problems, feeling

“somewhat overtaxed with the daily chores”. The

second scenario “higher need for support” premises

upon this, as 10 years have passed and the participant

is now in need for domestic part-time care. In both

scenarios, the family is described as not able to

support the participants enough, and details of health

and age-related problems are given.

The scenarios were chosen to appeal to most older

adults as no specific disease was chosen but a general,

age-related frailness and forgetfulness. The scenarios

were visualized with the drawing of an older adult

with the gender matching that of the interviewee.

2.1.2 The Use Cases

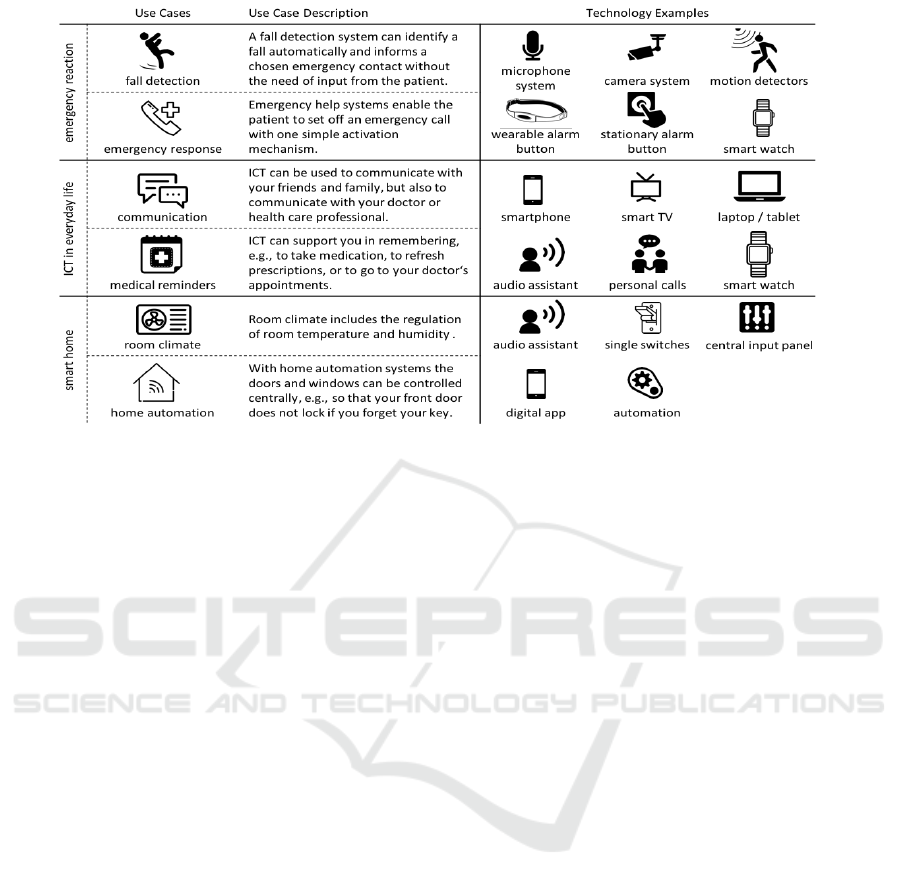

The applied use cases (see Figure 2) were conceptua-

lized to differ in their application frequency

(emergency cases vs. daily use), severity of conse-

quences (emergencies vs. facilitation of everyday

activities), and context (medical vs. non-medical).

Further, use cases were chosen that are not bound to

specific diseases, and thus, were applicable within the

scenarios. In order not to overwhelm the participants,

two use cases per application area were chosen in

which the technology examples stayed the same.

2.1.3 The Technology Examples

The technology examples (see Figure 2) were chosen

to be easily comprehensible and familiar to the

participants. The technology options were described

abstract enough to be widely applicable and familiar

to the participants (e.g., “a camera system”), but to

differ in important characteristics, e.g., perceived

privacy invasion, reliability, and performance in the

given use case.

2.2 The Sample

For this first stage of method-development, we

conducted six interviews with adults between 50 and

81 years who were recruited from the social network

of the interviewer. The participants’ mean age was

Figure 2: Overview of use case and technology descriptions (technology options do not presume to be complete).

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

128

59.3 years (SD = 13.0; Median = 52.5), four

participants were female, and two were male.

Education level, (previous) occupation, and living

circumstances (living alone or with family/spouses)

varied between the participants. All participants use

some common ICT technologies at least daily, and the

reported levels of technical self-efficacy differed

between low (1.5) and very high (4) (min=1, max=4,

M=2.5, SD=0.9). Knowledge and hands-on

experience with AAL technologies was very low

(n=1). Further, the sample consisted of predominantly

healthy older adults as only two out of six participants

indicated to suffer from a chronic disease. Contrary to

expectations, this was not true for the two oldest

participants. All participants were German native

speakers and no compensation was given for

participation.

3 RESULTS

In the following, we first focus on the barriers and

benefits in the first scenario, before addressing the

change in motives when the necessity of technology

use changes with the introduction of the second

scenario, thus, when voluntary use of the technology

changes into a vital use of the technology. Finally, we

examine the methodological implications of this

approach.

3.1 Barriers and Benefits in a Scenario

of “Moderate Need of Support”

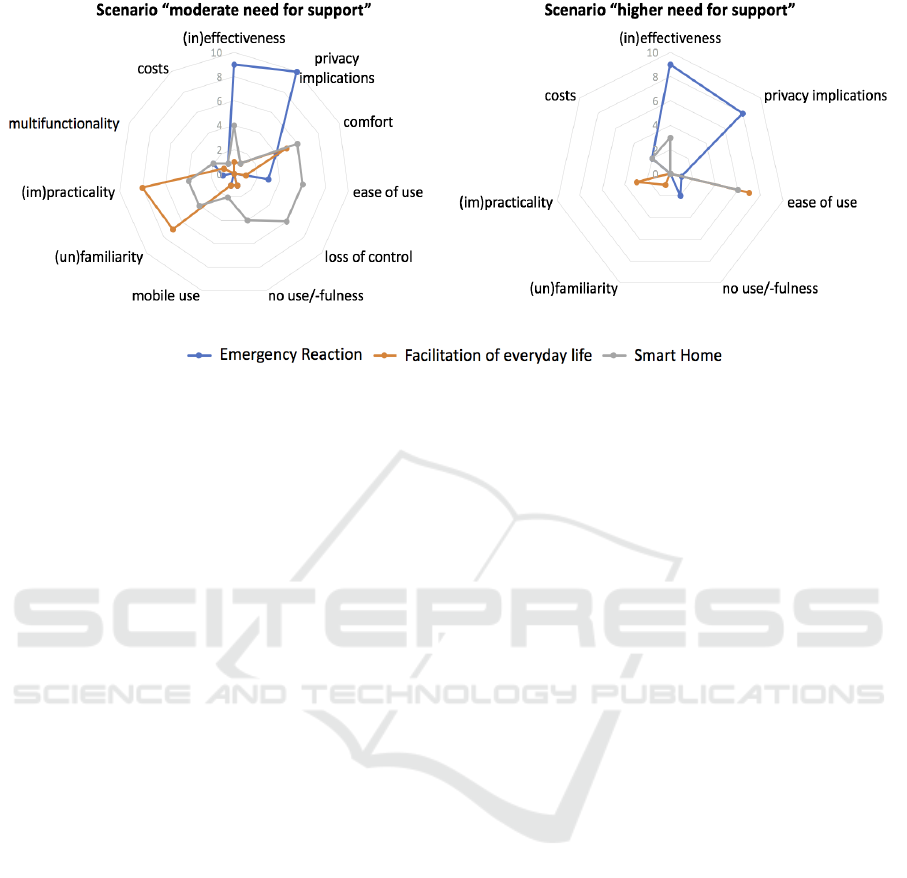

Figure 3 depicts the benefits and barriers that were

addressed by the participants. In the scenario of

“moderate need for support” the perceived

effectiveness and usefulness of the technologies was

the most important benefit (and if missing, barrier).

For example, in the case of emergency reaction,

increased security is most important, and those

technologies are rejected that are perceived to be

ineffective in raising an alarm:

“If I fall, it would surely not be exactly next to the alarm

button. So, it is no use.” (w50)

“The wearable alarm button, I would probably forget to

wear it” (m53)

Additionally, the participants did not always perceive

the technologies as useful, e.g., the oldest participant

does not want to be found after a fall, successfully

uses alternatives, and perceives too much support as

not helpful in old age:

“Only to live 3 weeks longer? I don’t need technology for

that. […] These technologies do not make life longer,

they just lengthen dying. […] You have to rely on God.

God will arrange that. If you die, it shall be.” (w81)

„I have a pocket diary that I use frequently. Everything

important is in there. And for my medicine, I have this

box with one compartment for every weekday. I use that

all the time, and I never have problems.” (w81)

“I like to still use my brain. Too much support isn’t

good.” (w81)

In the case of emergency reaction technologies,

privacy implications are the greatest barrier and a

trade-off between privacy and usefulness could be

observed. The participants chose the technology that

they deem as most effective (in detecting the fall or

Figure 3: Number of mentions of the different topics in scenario “moderate need for support” (left) and scenario “higher need

for support” (right).

A Game of Wants and Needs

129

raising the alarm, respectively) and which they can

still tolerate in its privacy violations.

„It is a trade-off between privacy implications, loss of

control, and so on, and whether it is safer and more

effective.” (w50)

“I would never use a camera system, because I would feel

watched, under surveillance. […] And because of the

security of my data, that you never know who can get

access to the videos.” (w52)

Being less privacy invasive than cameras emerged as

benefit of other fall detection technologies. Cameras

were rejected by all participants in this scenario as too

privacy invasive. Concerns about privacy and data

security were also mentioned for the other technology

areas, as well as missing trust in the reliability of

technologies, dependence on technology, and loss of

control.

“Misuse of data, data security, that you are online, you

can never be sure that it has not been hacked by

someone.” (m53)

“Automation is out of the question for me. It would be a

loss of control, too much dependence on the technology.

What happens when the automation does not work

correctly?” (w52)

“The audio assistant, I would not trust it to work well.

Probably I just talk to someone and the temperature

changes all the time without me controlling it.” (w50)

As a very important theme in the context of smart

home and everyday life technologies, (im)practicality

issues emerged, e.g. to have the technologies handy,

to already own compatible devices, or to be used to

the devices. The perception of practicality of the

different technologies varied very much between the

participants, depending on their individual habits and

preferences. Familiarity is often related to the

perception of practicality, and routines should not be

disturbed by new technologies:

“Because I already use a smartphone and I also enter

reminders in there today. I would just do the same in

older age. I wouldn’t need a device, TV or tablet, that

would be turned off anyway in the moment I need it. It

[the new device] would then need to be running all the

time. That is annoying.” (m53)

Also, practicality is related to effectiveness for the

desired function:

“Better than the other devices because it has the largest

display. And then the personal interaction is foreground,

it is the most important thing.” (w50)

Mobile use is another benefit or rather condition

related to impracticality.

“I would not use my laptop or smart TV, because, on the

one hand, I do not sit in front of the TV all the time or use

the laptop, and on the other hand, I can’t take it with me.

I want to be reminded wherever I am, if it is important.”

(w52)

Comfort is also a relevant benefit of some

technologies, even for fall detection, but the

perception of what is comfortable is very individual.

One results of the comparison of different

technological areas in one interview, is the

recognition of multifunctionality as key benefit of

integrated systems. It is not handy for older adults to

use many different technology, but they rather want

one system for many purposes:

“I would choose the technology that offers the most

functions so that I don’t need to switch technologies that

often.” (w52)

Another often addressed theme is the ease of use of

technologies, that is connected to being familiar with

technologies and feeling competent in interacting

with them.

“I would use the laptop. Maybe because I already feel

safe with it, I know how to use it and I am used to it. Other

people use it to. It is just familiar.” (w52)

“I could think about using an app or audio assistant, but

only if they are easy to use.” (w52)

Only twice costs were mentioned as barrier. Both

times, they were weighted against the usefulness of

the technology:

“To install this in the last years of your life. That’s not

worth the money. I would rather do something else with

the money.” (w81)

3.2 The Scenario with Higher Need for

Support

In the second part of the game, the scenario with the

increased necessity of medical technology (“higher

need for support”) was introduced and the

participants were asked to state any changes in choice

of technology and their reasoning. Only one

participant stated that nothing would change.

Especially in the case of fall detection and alarm

response, privacy concerns were overridden by the

desire for safety and help.

“I would now choose the safest system, for example the

motion detectors, if someone told me that it is sufficient.

It depends on the effectiveness of the system. If someone

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

130

told me, the motion detector is not that reliant, I would

choose a combination of microphones and motion

detectors. And if the camera system is the only safe and

effective option, and it is really necessary because I

experienced some falls, then I would be okay with

cameras.” (w52)

“Now I would take everything. Cameras, microphones,

motion detectors. I would take whatever makes me feel

safest, where the probability is highest to help me in case

of emergency.” (w52)

“Then, data security, protection of privacy and so on

wouldn’t be as important any more as survival.” (w52)

For the other two application areas, the ease of use

becomes the central argument for technology choice.

“I would now choose the automation, then I am on the

safe side. With the other systems, I could forget how to

use it or forget to activate them or so. The interaction

would be too complex and I couldn’t trust myself to

control them.” (w52)

In figure 3, the topics that the participants addressed

are depicted in comparison of the two scenarios. In

scenario “higher need for support”, the participants

included fewer factors in their reasoning than in

scenario “moderate need for support”. This can, on

the one hand, be explained by the order of the

scenarios and that they had already made up their

mind for the most decisive reasons. On the other

hand, the relevance of the factors seemed to shift.

Being found after a fall in the scenario “higher need

for support”, was much more important than privacy

implications. In contrast in the scenario “moderate

need for support”, privacy implications overrode the

increase in effectiveness. Comfort or loss of control

may just not be important anymore in this scenario,

or not enough important to be addressed.

3.3 Methodological Results

Only two participants commented directly on the

game-based interview. A 52-year-old woman found

the game-based approach “a very good idea for older

people with these playing cards to support their

memory”, and another 52-year-old woman said that it

was “all in all, very diverting, interesting, and felt to

be very short”. Even the oldest participants did not

appear to forget details or to be overtaxed by the

length of the interview. All participants participated

actively and showed interest.

The wording the participants used is one indicator

that the participants really put themselves into the

scenarios and evaluated the technologies for their

own lives. Most statements were phrased in the first

person, as in the following example and the quotes

above: “If I fall, I can’t reach it [the button].” (m71)

Moreover, the reasoning was larded with references

to personal habits and the participant’s own homes

and lifestyles.

“I won’t be watching TV all the time. I will be in my

garden very often just like now.” (w52)

“I just am a person that needs a button to touch, for

haptics and the feeling of it.” (w52)

The barriers and benefits for using and choosing a

technology differed depending on the application

areas and the scenarios, amongst other factors.

Therefore, a comparison to previous studies is

difficult. Moreover, qualitative studies do not aim at

weighting or quantifying the relevance of the

identified factors. This preliminary study with only

six participants does not presume to be representative.

Still, whether factors are included into the reasoning

of the participants indicates at least whether they are

influencing factors in the individual case.

Peek et al. (2014) conducted a literature review of

studies to summarize the factors influencing

acceptance of technologies for aging in place. They

also provided a count of the number of articles that

mentioned each factor. High costs and privacy

implications are the most often addressed concerns.

Ease of use, ineffectiveness and impracticality of the

medical technology – factors that were decisive in this

study – only appeared in two of 16 previous studies.

The participants in this study identified many details

we put into the category labelled “(im)practicality”.

These are situations, in which the technologies

oppose routines or cannot exploit their full potential

because of the habits or domestic situations of the

participants. Additionally, issues of ease of use,

familiarity with the devices, and comfort were often

named by the participants. This shows that the

participants in this game-based approach imagined

the presented technologies in their own homes and

lives and under the conditions of their own routines

and preferences.

Another result was that the absence of one barrier

became a benefit and the other way around. For

example, in the case of fall detection it is a benefit for

motion detectors to be less privacy-invasive than

microphones and cameras. The participants, thus,

chose the best of the given alternatives.

4 DISCUSSION

This paper presented a new game-based interview

method for the assessment of AAL acceptance

A Game of Wants and Needs

131

criteria. This qualitative approach aimed at

identifying barriers and benefits in comparison of

several AAL technologies, the comparison of

different use cases, and situations of differing

perceived necessity for care. Visualizations, personal

scenarios, and the task to choose between technology

alternatives led to a situation more comparable to real

decision or purchase situations than evaluating one

system alone. The results of the first interviews with

six older adults (aged 50 to 81 years) show that this

playful approach empowers the participants to fully

empathize with high-maintenance situations in older

life and to evaluate technology use in these situations.

4.1 Acceptance Criteria

The acceptance criteria addressed by our participants

have been reported in previous studies (e.g., Peek et

al. 2014). However, the empathic, playful approach

and to let participants choose between technology

alternatives identified a shift of relevance of known

barriers and benefits and a new angle to them.

Practicality and effectiveness were the key benefits,

or barriers respectively, in this study together with

privacy implications. Ease of use and comfort also

gained more importance than in previous reports. At

the same time, the comparison between technologies

leads to new benefits in a way that being less privacy-

invasive or more comfortable than other alternatives

become perceived benefits and barriers. Abstract

motives for the decision to use technology at all in a

use case, like increased security, quality of life, were

mostly not named directly by the participants in this

study. The focus lay on the benefits and barriers of

the technology options in comparison to each other.

Still, those higher-level motives and barriers could be

derived from the arguments of the participants. For

example, one of the decisive categories in this study

was labelled (in)effectiveness, which shows that the

perceived usefulness is still foreground. But if the

users trust all technologies to fulfill their main

function, other characteristics are important for the

choice between technology.

Here, the results indicated, that AAL systems and

products should put a greater focus on the

practicability and match for the users’ everyday life.

Nowadays, many ICT devices exists also in older

people’s households. Still, the ease of use is a critical

factor. Thus, developing AAL technologies, that

work on or similar to familiar devices can be a key

issue for market success.

In the context of the two scenarios, the weighting

between barriers and benefits as a basis for

technology choice becomes plain. While privacy

implications hindered technology acceptance in a

scenario of moderate need for support, in the scenario

of higher need for support the increased effectiveness,

and hence increased security, was the most important

factor which outweighed privacy implications. This

cost-benefit calculation has been labelled privacy

calculus and has been extensively studied in other

contexts (e.g., Laufer & Wolfe, 1977; Dinev & Hart,

2006). The privacy calculus theory could provide a

good framework for further analysis of this privacy/

usefulness trade-off in AAL acceptance

4.2 Method Evaluation

The new game-based approach proved useful in

providing a more realistic evaluation situation. On the

one hand, the approach gets the participants to be

deeper involved in the evaluation in comparison to

more abstract interviews. On the other hand, the

approach does not overwhelm the participants but

brings them to empathize with the proposed scenarios

and different necessities of support. The participants

relate the technology evaluation to their own

preferences, habits hobbies, routines, and domestic

situations. This can not only be seen in their wording,

but also in the shift towards practicality issues as

important assessment criteria.

Our approach puts a different focus than common

system evaluations that has been missing in AAL

research until now: the distinction between benefits

and barriers that lead to technology use at all and

those that lead to one technology being preferred over

alternatives. As the market for AAL technologies is

constantly growing and hence the range of products

increases, this new focus is important.

In this paper, the first results with the new game-

based method were presented. The approach offers

the possibility to be converted to a digital game or to

be adapted to a new questionnaire approach, to

quantify the results. We saw that the participants

differed in their emphasis of different benefits and

barriers. This raises the question, if user factors shape

the perception of the factors. Also, the influence of

the individuals’ attitudes towards aging could

contribute to understand older adults’ choices and

acceptance patterns.

4.3 Limitations and Future Research

The applied playful qualitative approach was a

preliminary study to evaluate the method. It proved

useful in getting the participants to empathize with

high-maintenance situations and different necessities

of support, but its representativeness is

methodologically limited.

Content analysis is a useful tool for summarizing

and categorizing interview data, but is influenced by

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

132

the individual coders. By engaging three coders who

viewed the whole material, intercoder reliability was

aimed for. Additionally, initial categories were based

on the literature review, but needed to be

supplemented and adapted to the context and the

participants’ arguments. It would be useful for future

studies to expand the game structure to other

technologies and use cases in order to enable direct

comparisons between technologies and use cases.

Additionally, it would also be possible to incorporate

the characteristics of our playful approach into

quantitative research, e.g., by using similar

instructions, scenarios, and introductory questions

within a digital version of the game.

As it was a preliminary study, the sample size was

very small: future studies should aim for a replication

of the playful interview approach addressing a larger

sample. As previous qualitative and quantitative

studies showed, that the acceptance of assisting

technologies is shaped by individual characteristics of

diverse user groups (Wilkowska et al., 2012; van

Heek et al., 2017), a replication with a larger sample

would also enable a detailed investigation of user

diversity influences on a personal evaluation of

technologies and motives as well as barriers to use

specific technologies. As a last sample-related aspect,

the present study was conducted in a single country:

Germany. For future studies, this study’s approach

should be applied in other countries in order to

compare personal evaluations of assisting

technologies depending on different cultures,

backgrounds, and their specific healthcare systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all participants for their patience

and openness to share their opinions. Furthermore,

the authors want to thank Nils Plettenberg and

Jennifer Kirstgen for research assistance.

REFERENCES

Beier, G. (1999). Kontrollüberzeugungen im Umgang mit

Technik. Report Psychologie, 684–693.

Blackman, S., Matlo, C., Bobrovitskiy, C., Waldoch, A.,

Fang, M. L., Jackson, P., Mihailidis, A., Nygard, L.,

Astell, A., & Sixsmith, A. (2016). Ambient Assisted

Living Technologies for Aging Well: A Scoping

Review. Journal of Intelligent Systems, 25(1), 55–69.

Davis, F., Bagozzi, R., & Warshaw, P. (1989). User

Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison

of Two Theoretical Models. ManagE. Sci., 35(8), 982.

Dinev, T. & Hart, P., (2006). An Extended Privacy Calculus

Model for E-Commerce Transactions. Information

Systems Research, 17(1), 61–80.

Jaschinski, C. & Allouch, S. B. (2015). An extended view

on benefits and barriers of ambient assisted living

solutions. International Journal on Advances in Life

Sciences, 7(1–2), 40–53.

Laufer, R.S. & Wolfe, M., 1977. Privacy as a Concept and

a Social Issue: A Multidimensional Developmental

Theory. Journal of Social Issues, 33(3), pp.22–42.

Mayring, P. (2010). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. [Qualitative

Content Analysis]. Handbuch qualitative Forschung in

der Psychologie, 601-613.

Memon, M., Wagner, S. R., Pedersen, C. F., Beevi, F. H.

A., & Hansen, F. O. (2014). Ambient assisted living

healthcare frameworks, platforms, standards, and

quality attributes. Sensors, 14(3), 4312-4341.

Merkel, S. (2016). Technische Unterstützung für mehr

Gesundheit und Lebensqualität im Alter:

Herausforderungen und Chancen. [Technical assist for

more health and life quality in age: challenges and

opportunities]. No 07/2016, Forschung Aktuell, Institut

Arbeit und Technik (IAT), Westfälische Hochschule,

University of Applied Sciences.

Munoz, D., Gutierrez, F. J., & Ochoa, S. F. (2015).

Introducing Ambient Assisted Living Technology at

the Home of the Elderly: Challenges and Lessons

Learned. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol.

9455).

Peek, S. T. M., Wouters, E. J. M., van Hoof, J., Luijkx, K.

G., Boeije, H. R., & Vrijhoef, H. J. M. (2014). Factors

influencing acceptance of technology for aging in

place: A systematic review. International Journal of

Medical Informatics, 83(4), 235-248.

Peek, S. T. M., Luijks, K. G., Rijnaard, M. D., Nieboer, M.

E. , Van der Voort, C. S., Aarts, S., Van Hoof, J.,

Vrijhoef, H. J. M., & Wouters, E. J. M. (2016). Older

Adults’ Reasons for Using Technology while Aging in

Place. Gerontology, 62(2), 226–237.

Van Heek, J., Himmel, S., Ziefle, M. (2017). Helpful but

Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-Systems Contrasting

User Groups with focus on Disabilities and Care

Needs'. Proceedings of the International Conference on

ICT for Aging well (ICT4AWE 2017), 78-90.

Walker, A., Maltby, T. (2012). Active ageing: A strategic

policy solution to demographic ageing in the European

Union. Int. J. Social Welfare, 21, 117-130.

Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A., Guberman, N., Reeve, J., Allen,

R. E. S. (2011). The Meaning of “Ageing in Place” to

Older People. The Gerontologist, gnr098.

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M., Alagöz, F. (2012). How user

diversity and country of origin impact the readiness to

adopt E-health technologies: an intercultural

comparison. Work (Reading, Mass.), 41 Suppl 1, 2072–

2080.

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M., & Himmel, S. (2015).

Perceptions of Personal Privacy in Smart Home

Technologies: Do User Assessments Vary Depending

on the Research Method? Lecture Notes in Computer

Science, 9190, 436–448.

A Game of Wants and Needs

133