Impact of Online Health Information on

Patient-physician Relationship and Adherence;

Extending Health-belief Model for Online Contexts

Tahir Hameed

SolBridge International School of Business, Daejeon, Republic of Korea

Keywords: Online Health Information, Patient-physician Relationship, Health-belief Model, Adherence, Health

Behavior.

Abstract: Physicians have information advantage over patients in terms of professional knowledge and expertise,

implying patients have to fully depend on them for diagnosis, prescription and treatment. However, in the

wake of abundant online health information (OHI) on the internet and through mobile apps, these days patients

appear to be better-informed when approaching their physicians. As per health-belief model, patients would

be motivated better to adhere to physicians’ prescribed treatments if they feel threatened by their symptoms

and/or when they are convinced about the benefits of the treatment. This research proposes improved health-

belief model incorporating use of OHI. It identifies different types of OHI shaping up patients’ perceptions

prior to interactions with physicians. It suggests that patient-physician meetings (relationship) and consequent

adherence behavior of the patients are inter-related and deeply affected by the initial perceptions of the

patients based on consumed OHI. The proposed model is being tested using anonymous survey data collected

immediately after patient-physician meetings in clinics/hospitals and subsequent adherence data from the

same patients. Key contribution of this paper is combining individual’s information behavior with health

behavior which provides much better understanding for management of emergent healthcare delivery models

in the digital economy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nature of the patient-physician relationship plays an

important role in patient outcomes and well-being

(Kaplan et al., 1989). Traditionally, physicians have

held an advantage over patients in terms of

professional knowledge and expertise which implied

patients were fully dependent on physicians for

diagnosis, treatment options and prescriptions.

However, in the wake of abundant online health

information (OHI) on the internet and mobile apps,

these days patients appear to be better-informed when

approaching their physicians (Wald et al., 2007).

While several physicians look at the “informed

patient” in a positive way, a large number of

physicians also consider OHI a source of problems

and in-efficiencies in their diagnosis and treatment

procedures (McMullan, 2006, Rosenstein, 2015).

Informed patients tend to ask more questions during

consultation meetings, would like to discuss

alternative treatment options, are not convinced easily

on prescriptions and might choose not to engage in

further communications (Chung, 2013, Dedding et

al., 2011). Consequent patient-physician relationship,

formed on the basis of authority (from professional

expertise) and mutual trust could deteriorate,

ultimately leading to negative changes in the patient’s

health behavior.

There is a large emerging body of e-health

research, but in case of patient-physician interactions

and relationship, it is focused more on the physician’s

behavior and attitude or the meeting itself (Assis-

Hassid et al., 2016, Rosenstein, 2015); systematic

studies on linking patient-physician relation to

outcomes are largely missing (Clayman et al., 2016).

On the other hand, patient’s ensuing health behavior

and its antecedents have not been discussed to the best

of our knowledge.

Therefore, this version of our larger research,

constructs a theoretical model to study patient’s

health behavior, especially adherence, in the wake of

OHI consumption and changing nature of patient-

physician’s meetings. The second section of the paper

Hameed, T.

Impact of Online Health Information on Patient-physician Relationship and Adherence; Extending Health-belief Model for Online Contexts.

DOI: 10.5220/0006720905910597

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2018) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 591-597

ISBN: 978-989-758-281-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

591

covers literature review, while third section discusses

the research model at some length. Fourth and the

concluding section discusses the progress and future

directions of this research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND

THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

2.1 Online Health Information Search

Online health information (OHI) search has emerged

as one of the most prolific uses of the internet.

According to (Fox, 2011, Fox and Duggan, 2015),

OHI search is taking a new social life of its own in the

internet.

OHI seekers typically search information about

symptoms, diagnosis, diseases, treatment options and

their effectiveness, while many of them also share

their own experiences about the above with others

(Hameed and Swar, 2015, Frost and Massagli, 2008,

Ba and Wang, 2013). On top of making sense of the

medical information, OHI seekers, especially if they

are diagnosed patients or their caretakers, also seek

information about hospitals, clinics, doctors and

interactions and outcomes of other patients with them

(McMullan, 2006). In general, almost everyone at

some point seek OHI about general well-being,

exercise, and diet and disease prevention.

2.2 Patient-physician Relationship

Charles et al. (1999) defined “patient-physician

relationship” (PPR) as a medical encounter which

involves shared decision-making and needs

consideration on the part of the physician for

considering different patient positions. However, in

contrast to “patient-physician communications”, PPR

could be generally considered multiple encounters

involving diagnosis, interpretation of medical

records, prescriptions and treatments/interventions.

The quality of PPR has direct relationship with

patient’s outcomes including patient’s willingness to

adhere to the prescribed treatment. (Kaplan et al.,

1989) were among early scholars who pointed out

“physician-patient relationship may be an important

influence on patients' health outcomes and must be

taken into account in light of current changes in the

health care delivery system that may place this

relationship at risk”.

PPR’s two main components include emotional

and informational aspects. Successful healtchare and

intervention requires strong patient-physician

communication. Emotional components include

genuineness, trust, respect, empathy, warmth and

acceptance (Ong et al., 1995). Informational

components include exchanging and sharing medical

information, educating patients and providing quality

medical management. Most patients' complaints and

displeasure arise from breakdown of the relationship

and communication with the physicians.

As noted previously about OHI, these days

patients may treat internet as a substitute or

supplement to traditional sources of health

information (Kitchens et al., 2014). Some people go

to the extent of self-diagnosing their symptoms

online. Hesse et al. (2005) noted that “most

physicians are already experiencing the effects of

patients showing up to their offices armed with

printouts from the World Wide Web and requesting

certain procedures, tests, or medications”.

Several physicians consider “informed patient” as

a participant in their health decisions, however a large

number of physicians also consider OHI a source of

problems and in-efficiencies in their diagnosis and

treatment decisions (McMullan, 2006, Rosenstein,

2015). Therefore, some physicians engage in

disruptive behavior during interactions with their

patients with negative implications for patient’s well-

being and healthcare delivery (Rosenstein, 2015,

Rosenstein and O’daniel, 2005).

Patients might find it hard to challenge their

physician or may not be able to insist for alternatives

due to physician’s knowledge, however it is easy for

them to disengage and ignore physician’s advice on

the spot or after the meetings. In fact, Quill and Brody

(1996) proposed that keeping a balance between

physician’s power and patients autonomy in choosing

the best treatment options would be better for the

well-being of the patients ultimately.

2.3 Health Behavior

Health behavior generally refers to one’s behavioral

actions with an awareness of their health outcomes

(positive or negative). Medical professionals and

policy makers are deeply interested in promoting

preventive health behaviors that could save the

burden on and costs of provision of healthcare

services (unhealthy practise such as smoking, etc.) by

reducing unnecessary negative health outcomes.

Adherence is one of the most common health

behavior which refers to one’s tendency to follow the

prescribed routine treatment or intervention gradually

reducing the illness symptoms or not worsening them

any further. Regular visitations of hospitals and

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

592

preventive screening for highly likely infections or

diseases are also counted as positive health behavior.

Bering receptive and engaging positively with the

physician would also be counted as a positive health

behavior on the part of patients.

Change in health behaviors and corresponding

interventions have been studied from numerous

perspectives including social-psychological and

socio-cognitive (e.g. theory of planned behavior and

health-belief models), social-ecological and staged

perspectives (such as precede-proceed model),

among others (Glanz et al., 2008). This paper is

particularly interested in the former two approaches

which are discussed and incorporated to build a

theoretical research model in the next section.

3 RESEARCH MODEL AND

HYPOTHESES SETTING

In this section, health behavior of online informed

patients is conceptualized specifically through the

theoretical lenses of health-belief model and theory of

planned behavior.

3.1 Health Belief Model

As noted in the health behavior section, health-belief

model is one of the primary theoretical frameworks

for explaining preventive health behavior of people.

Godfrey Hochbaum, Stephen Kegels and Irwin

Rosenstock originated research on Health Belief

Model (HBM) to predict preventive health behavior

in a systematic way. They attempted to identify

factors behind pre-emptive decisions to obtain a chest

x-ray for early detection of tuberculosis as early as

1950s. HBM generally rests on social-psychological

theories trying to correlate belief patterns (perceptual

worlds) of patients with their health behaviors

(Rosenstock, 1990, Rosenstock, 1974).

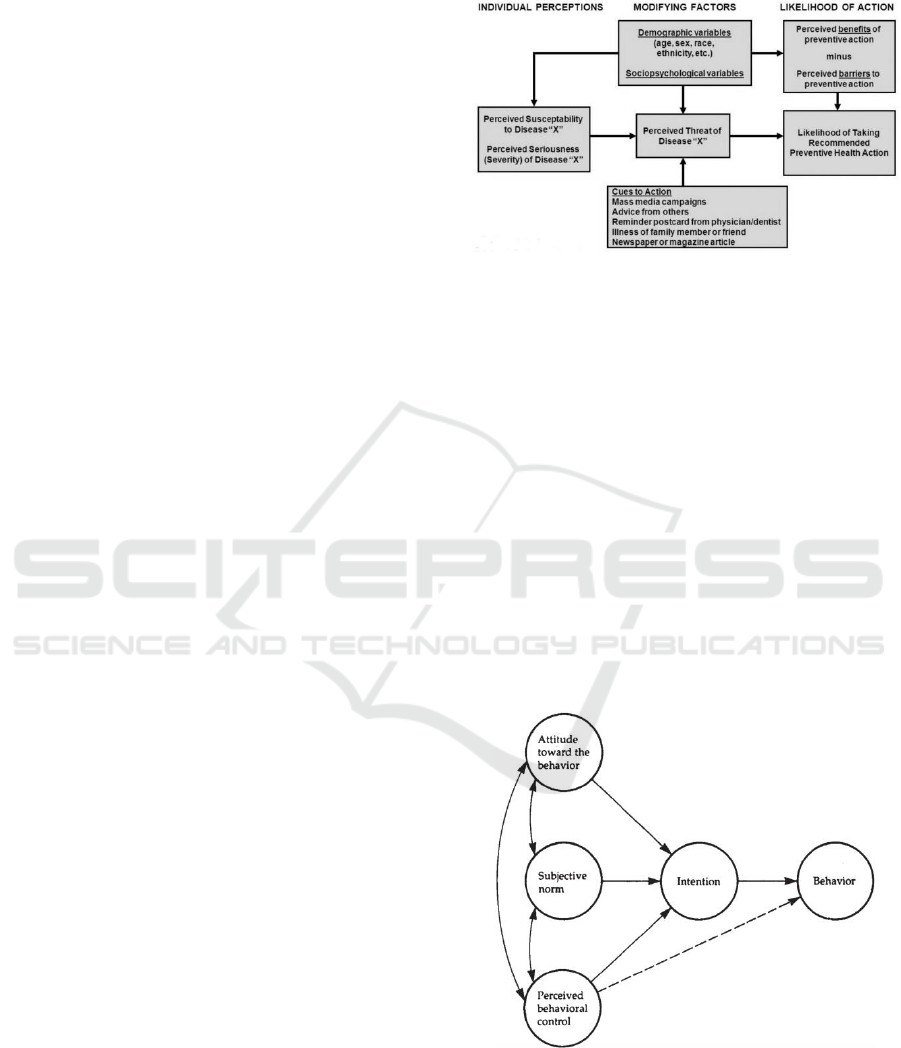

There are three categories of a person’s

motivation to undertake a positive or negative health

behavior: individual perceptions, modifying

behaviors, and likelihood of action (Rosenstock,

1990, Janz and Becker, 1984). Individual perceptions

about the current level of illness, disease or well-

being shape the individual’s perceived susceptibility

and perceived severity. A higher susceptibility and

severity of a disease could be life threatening,

therefore motivating a person highly to save himself

by changing his or her behavior radically. Modifying

factors include demographic variables, perceived

threat, and cues to action. The likelihood of action is

related with factors driving probability of appropriate

health behavior (Janz and Becker, 1984) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Health Belief Model (Adapted from Becker and

Janz, 1985).

Social Learning Theory adds to HBM by

demonstrating there could be multiple sources of

acquiring new expectations or learning through

imitating others or even improving self-efficacy.

3.2 Theory of Planned Behavior

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1985) and

the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Fishbein and

Ajzen, 1975) help in predicting behavioral intention

and subsequent behavioural actions of actors. TPB

proposes individual behavior is driven by three

factors, namely individual’s attitude, subjective

norms, and the individual’s perception of the ease or

control consequent to the situations arising from that

behavior (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Theory of Planned Behavior (Adapted from

Ajzen, 1985).

Attitude generally refers to the positive or

negative about a behavior which could be assessed

through one’s beliefs about consequences of the

Impact of Online Health Information on Patient-physician Relationship and Adherence; Extending Health-belief Model for Online Contexts

593

behavior and their desirability. Subjective norm is the

perception of individual about how divergent or

convergent the behavior would be in the opinion of

people surrounding the individual. Lastly, behavioral

control refers to the perceived difficulty in

performing a behavior.

Therefore, in the healthcare domain, it is not

difficult to discern that patient’s health behavior

(action), for example actual behavior of not

communicating or engaging effectively with the

physician should logically be preceded by an

intention to engage.

However, in this case, it would be critical to note

how attitudes, norms and perceived control are

altered by online health information and modified

health-beliefs. Yun and Park (2010) demonstrated

that consumers’ health consciousness, perceived

health risk and Internet health information use

efficacy influenced consumers’ beliefs, attitude and

intention of use of disease information on the Internet.

In another study, (Mills and Todorova, 2016)

presented the opposite view; they looked at the

propensity of susceptibility and severity of one’s

illness in shaping up their OHI search behavior.

However, this paper is taking a position that once

OHI is obtained information-seekers perceptions of

susceptibility and severity might be affected.

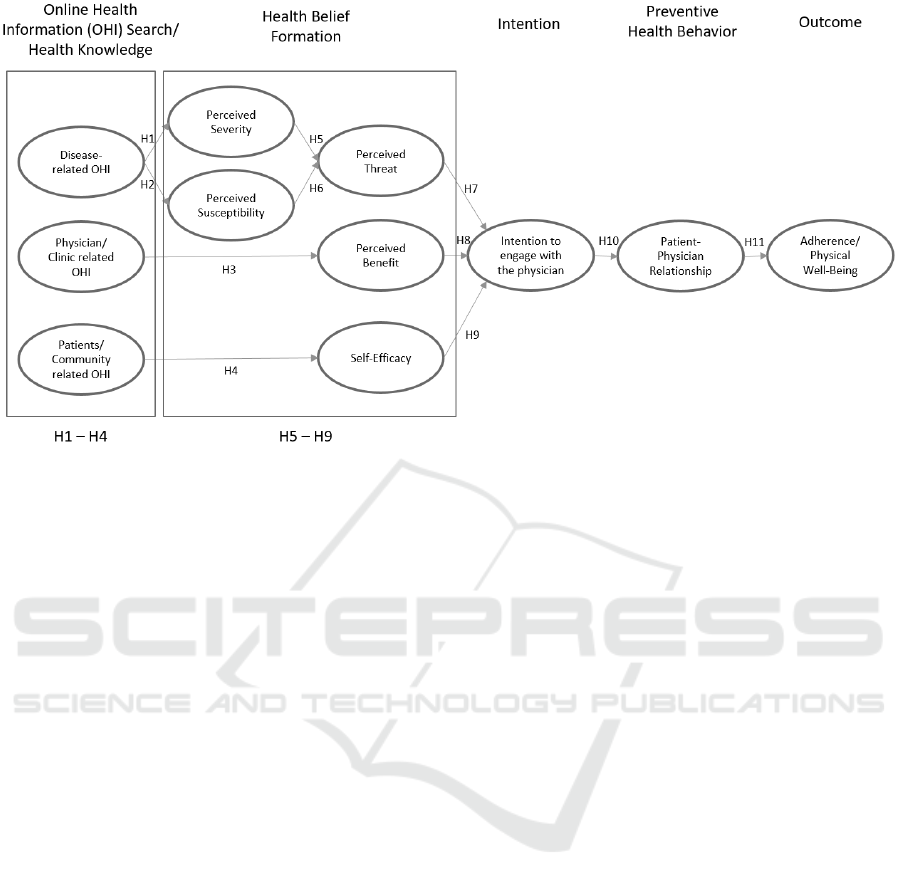

3.3 Extended Health-belief Model

Incorporating Online Health

Information Behavior

An original model (Figure 3) has been developed

amalgamating the theoretical concepts discussed

above i.e. health-belief model and the theory of

planned behavior. Discussion on the model follows.

3.3.1 Hypotheses 1-6: Online Health

Information Search and Health Belief

Formation

OHI sought could be generally categorized into three

categories, namely disease-related information,

physician or clinic related information (including

patient reviews and feedback) and finally the

community related information (experiences and

discussions on effectiveness of treatments, drugs and

interventions) (McMullan, 2006, Frost and Massagli,

2008).

Each type of information relates to different parts

of patient’s belief systems (or patterns). Disease-

related OHI affects perceived severity and severity of

symptoms and diagnostics results, therefore adding to

perceived threat to the life of a person. Therefore,

hypotheses 1-2 and hypotheses 5-6 establish

associations between disease-related OHI and

perceived threat as follows.

H1: Negative disease–related online health

information for one’s symptoms is positively

associated with higher levels of perceived severity

H2: Negative disease–related online health

information for one’s symptoms is positively

associated with higher levels of perceived

susceptibility

H5: Higher levels of perceived severity are

positively associated with perceived threats (to

life/well-being)

H6: Higher levels of perceived susceptibility are

positively associated with perceived threats (to

life/well-being)

Practitioner, hospital or clinic related information

typically drives ones perceptions about the potential

benefits or outcomes (recuperating from the disease).

The following hypothesis is therefore established.

H3: Positive reviews in the practitioner or clinic-

related online health information associate positively

with higher degree of perceived benefits

Finally, information-sharing in online health

communities contributes to self-confidence and self-

regulation of OHI seekers by knowing about the

experiences of others and comparing them with one’s

own (Ba and Wang, 2013, Frost and Massagli, 2008).

That leads us to propose the following hypothesis.

H4: High number of positive experiences (of

recuperation and adherence) in the community-

related online health information from the people

experiencing similar symptoms promotes higher

levels of self-efficacy

3.3.2 Hypotheses 7-9: Health Belief

Formation and Intention to Engage

with the Physician

Firmed health beliefs of patients regarding threats

would normally reflect their attitude towards

upcoming physician interactions. Patients with higher

levels of perceived life threats would like to get

clearer answers, firm assurances, and would be

willing to try interventions with bigger risks (even

asking for medically incorrect treatments) (Iverson et

al., 2008). Therefore, they would form an intention to

dig deeper, share their acquired OHI in low tone, and

be willing to understand and listen to the physician

more keenly. As a result, a positive relationship

should arise between the patient and the physician

leading to the following hypothesis:

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

594

Figure 3: Extended Health-Belief Model incorporating online health information behavior (Source: Author).

H7: A high level of perceived health threats is

positively associated with intentions to positively

engage with the physician and vice versa

On the other hand, a higher level of perceived

benefits, based on the reputation of the physician or

hospital, should also wield similar psychological

effects on the patients’ intentions to engage with the

physician. Such effects come from our tendency to

accept the authority attached with knowledge and

expertise. However, if the reviews are negative,

patients’ might generate the intention to engage

firmly or aggressively with the physician about the

consumed OHI which could generate friction, in

some cases even leading to physician’s disruptive

behavior (Rosenstein, 2015).

H8: A high level of perceived health benefits is

positively associated with intentions to positively

engage with the physician and vice versa

Finally, if one could find positive stories about

others with similar symptoms (threats) recuperating

or fighting back the diseases successfully should

increase one’s confidence. On communities like

patientslikeme.com where extensive comparative

data is available in the form of user feedback on

effectiveness of drugs, treatments and home

remedies, one could adapt own opinions about

previously prescribed drugs or treatments with some

degree of confidence. The following hypothesis

covers these scenarios.

H9: Higher level of self-efficacy leads to

intentions of engaging positively with the physician

3.3.3 Hypothesis 10: Intention to Engage

with the Physician and

Patient-physician Relationship

Since intentions are antecedents of behavior (actions)

in theory of planned behavior, firmed intentions to

engage positively or negatively with the physicians

are highly likely to generate the intended behavior

(Ong et al., 1995). The corresponding hypothesis

follows.

H10: Intentions to engage positively with the

physician is positively associated with the level of

satisfaction (and trust) of the patient-physician

relationship

3.3.4 Hypothesis 11: Patient-physician

Relationship and Adherence

Finally, it is well-established in the literature that

satisfactory and trustworthy (positive) patient-

physician relationships encourage patients to adhere

to the prescribed treatments and interventions

(Kaplan et al., 1989, Ong et al., 1995). The following

hypothesis is therefore quite discernable.

H11: Satisfactory patient-physician relation-ships

are positively associated with adherence levels by the

patients (hence recuperation) and vice versa

Impact of Online Health Information on Patient-physician Relationship and Adherence; Extending Health-belief Model for Online Contexts

595

4 PROGRESS, CONCLUSIONS

AND FUTURE WORK

The paper has proposed an original conceptual model

connecting the online health information behavior

and health behavior of the patients and online users in

an increasingly online world. Therefore, it aims to

provide much-needed understanding and implications

for changing roles of patient and physician

engagement in the emergent healthcare delivery

model contexts.

A survey has been developed including several

measurement items from published sources (already

tested for construct validity) for each construct shown

in the research model. It is targeted to be circulated to

partner hospitals in South Korea and other countries

with an expected completion rate of around three

hundred surveys. The survey will be administered by

qualified physicians or their staff members. The

adherence data would be collected from the same

patients by the same doctors (or their staff). A due

approval has been acquired from the author’s

institutional ethics board for conducting research

involving human subjects.

Once the data collection would be completed

(approximately 3-6 months), both the measurement

model and the structural model would be tested using

PLS-SEM (partial least squares- structural equation

modelling) approach. Further analysis would lead to

acceptance or negation of the hypotheses and their

underlying explanations.

Future research could consider to test other health

behavioural outcomes than adherence such as those

covered by RAND 36-item survey (Hays et al., 1993).

Additionally moderating or mediating roles of

physicians’ attitudes, physician’s competencies,

cultural differences and gender differences would

greatly enhance the understanding of this model.

Social exchange perspective appears to be an

interesting alternate perspective which could shed

further light on the nature of patient-physical

relationship in this context.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. 1985. From intentions to actions: A theory of

planned behavior, Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer. doi:

10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2.

Assis-Hassid, S., Heart, T., Reychav, I. & Pliskin, J. S.

2016. Modelling Factors Affecting Patient-Doctor-

Computer Communication in Primary Care.

International Journal of Reliable and Quality E-

Healthcare (IJRQEH), 5, 1-17. doi: 10.4018/IJRQEH.

2016010101.

Ba, S. & Wang, L. 2013. Digital health communities: The

effect of their motivation mechanisms. Decision

Support Systems, 55, 941-947. doi: doi.org/10.1016/

j.dss.2013.01.003.

Charles, C., Gafni, A. & Whelan, T. 1999. Decision-making

in the physician–patient encounter: revisiting the shared

treatment decision-making model. Social science &

medicine, 49, 651-661. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)

00145-8.

Chung, J. E. 2013. Patient–provider discussion of online

health information: results from the 2007 Health

Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). Journal

of health communication, 18, 627-648. doi:

10.1080/10810730.2012.743628.

Clayman, M. L., Bylund, C. L., Chewning, B. & Makoul,

G. 2016. The impact of patient participation in health

decisions within medical encounters: a systematic

review. Medical Decision Making, 36, 427-452. doi:

10.1177/0272989X15613530.

Dedding, C., van Doorn, R., Winkler, L. & Reis, R. 2011.

How will e-health affect patient participation in the

clinic? A review of e-health studies and the current

evidence for changes in the relationship between

medical professionals and patients. Social science &

medicine, 72, 49-53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.

10.017.

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention

and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research,

Reading, MA, Addison-Wesley.

Fox, S. 2011. The social life of health information 2011,

Pew Internet & American Life Project Washington,

DC.

Fox, S. & Duggan, M. 2015. Pew Internet and American

Life Project [Online]. Pew Research Center

Washington, DC. Available: http://www.pewinternet.

org/2015].

Frost, J. H. & Massagli, M. P. 2008. Social uses of personal

health information within PatientsLikeMe, an online

patient community: what can happen when patients

have access to one another’s data. Journal of medical

Internet research, 10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1053.

Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K. & Viswanath, K. 2008. Health

behavior and health education: theory, research, and

practice, John Wiley & Sons.

Hameed, T. & Swar, B. 2015. Social value and information

quality in online health information search.

Australasian Conference on Information Systems 2015

Adelaide. Australasian Conference on Information

Systems arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.03507

Hays, R. D., Sherbourne, C. D. & Mazel, R. M. 1993. The

rand 36‐item health survey 1.0. Health economics, 2,

217-227.

Hesse, B. W., Nelson, D. E., Kreps, G. L., Croyle, R. T.,

Arora, N. K., Rimer, B. K. & Viswanath, K. 2005. Trust

and sources of health information: the impact of the

Internet and its implications for health care providers:

findings from the first Health Information National

HEALTHINF 2018 - 11th International Conference on Health Informatics

596

Trends Survey. Archives of internal medicine, 165,

2618-2624. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2618.

Iverson, S. A., Howard, K. B. & Penney, B. K. 2008. Impact

of internet use on health-related behaviors and the

patient-physician relationship: a survey-based study

and review. Journal of the American Osteopathic

Association, 108, 699.

Janz, N. K. & Becker, M. H. 1984. The health belief model:

A decade later. Health Education & Behavior, 11, 1-47.

doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101.

Kaplan, S. H., Greenfield, S. & Ware Jr, J. E. 1989.

Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions

on the outcomes of chronic disease. Medical care,

S110-S127.

Kitchens, B., Harle, C. A. & Li, S. 2014. Quality of health-

related online search results. Decision Support Systems,

57, 454-462. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2012.10.050.

McMullan, M. 2006. Patients using the Internet to obtain

health information: how this affects the patient–health

professional relationship. Patient education and

counseling, 63, 24-28. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.006.

Mills, A. & Todorova, N. 2016. An integrated perspective

on factors influencing online health-information

seeking behaviours. Australasian Conference on

Information Systems, 5-7 Dec 2016. Wollongong.

Ong, L. M., De Haes, J. C., Hoos, A. M. & Lammes, F. B.

1995. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the

literature. Social science & medicine, 40, 903-918. doi:

10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-M

Quill, T. E. & Brody, H. 1996. Physician recommendations

and patient autonomy: finding a balance between

physician power and patient choice. Annals of internal

medicine, 125, 763-769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-

9-199611010-00010

Rosenstein, A. H. 2015. Physician disruptive behaviors:

Five year progress report. World journal of clinical

cases, 3, 930. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i11.930.

Rosenstein, A. H. & O’daniel, M. 2005. Disruptive

Behavior & Clinical Outcomes: Perceptions of Nurses

& Physicians. Nursing Management, 36, 18-28.

Rosenstock, I. M. 1974. Historical origins of the health

belief model. Health education monographs, 2, 328-

335. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200403

Rosenstock, I. M. 1990. The health belief model:

Explaining health behavior through expectancies. In:

Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K. & Viswanath, K. (Eds.) Health

behavior and health education: Theory, research, and

practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wald, H. S., Dube, C. E. & Anthony, D. C. 2007.

Untangling the Web—The impact of Internet use on

health care and the physician–patient relationship.

Patient education and counseling, 68, 218-224. doi:

10.1016/j.pec.2007.05.016.

Yun, E. K. & Park, H. 2010. Consumers’ disease

information–seeking behaviour on the Internet in

Korea. Journal of clinical nursing, 19, 2860-2868.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03187.x.

Impact of Online Health Information on Patient-physician Relationship and Adherence; Extending Health-belief Model for Online Contexts

597