Feasibility of Labor Induction Success Prediction based on Uterine

Myoelectric Activity Spectral Analysis

C. Benalcazar Parra

1

, A.I. Tendero

1

, Y.Ye-Lin

1

, J. Alberola-Rubio

2

, A. Perales Marin

2

,

J. Garcia-Casado

1

and G. Prats-Boluda

1

1

Centro de Investigación e Innovación en Bioingeniería, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Valencia, Spain

2

Obstetric service, Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe de Valencia, Valencia, Spain

Keywords: Labor Induction, Electrohysterogram, EHG, EHG-Bursts, Spectral Analysis, Deciles, Vaginal Delivery,

Cesarean Section, Active Phase of Labor.

Abstract: Labor induction using prostaglandins (PG) is a common practice to promote uterine contractions and to

facilitate cervical ripening. However, not all cases of labor inductions result in vaginal deliveries and it has

been associated with an increased risk of cesarean delivery. This last situation is associated to a greater

healthcare economic impact and to an increment in the maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity.

Obstetricians face different scenarios daily during a labor induction and it would be advantageous to be able

to infer the result of the labor induction for a better labor management. Uterine electrohysterogram (EHG)

has been proven to play an outstanding role in monitoring uterine dynamics and in characterizing the uterine

myoelectrical activity. Therefore, the aim of this study was to characterize and to compare the response of

uterine myoelectrical activity to labor induction drugs for different labor induction outcomes by obtaining and

analyzing the evolution of spectral parameters from EHG records picked up during the first 4 hours after labor

induction onset. Specifically, deciles from the EHG-bursts’ power spectral density (PSD) were worked out.

Our results showed that deciles D8 and D9 are able to discriminate between women who achieved active

phase of labor and those who did not. For women who achieved active phase of labor, D5 makes it possible

to separate women who delivered vaginally and those who underwent a cesarean section; finally D2-D6

enabled us to distinguish vaginal deliveries within 24 hours after induction onset from the other outcomes.

Thus, deciles computed from EHG PSD are potentially useful to discriminate the different outcomes of a

labor induction, suggesting the feasibility of induction success prediction based on EHG recording.

1 INTRODUCTION

Labor induction is an ordinary practice in obstetrics

whose objective is to induce a vaginal delivery. The

induction of labor is used in situations where maternal

and fetal risk of continuing pregnancy exceeds those

of termination of pregnancy. Approximately 23% of

all cases of birth in United states in 2012 were

performed with a previous induction (Hamilton et al.,

2012). It is a long process which can last many hours,

approximately 17-20 hours (Filho, Albuquerque and

Cecatti, 2010), and sometimes the waiting can be

extended to 36 hours. Pharmacologic methods for

cervical ripening and labor induction, such as

prostaglandins, have been used for decades (Gilstrop

and Sciscione, 2015) with the purpose of ripen the

cervix and stimulate uterine contractions. However,

this long and uncomfortable process does not ensure

a vaginal delivery and almost 20% of women that

have been induced end up labor with a cesarean

section (Seyb et al., 1999). This last implies the use

of more resources and longer hospital stays, both

associated to a greater healthcare cost when compared

with a spontaneous labor (Garcia-Simon et al., 2016).

Success of a labor induction has been defined as

vaginal delivery within 24 or 48 hours from labor

induction onset (Pandis et al., 2001; Indraccolo,

Scutiero and Greco, 2016) or vaginal delivery at any

time after labor induction onset (Ware and Raynor,

2000). From a pharmacological point of view, a labor

induction is considered successful if drug action

provokes women to achieve active phase of labor

(Baños et al., 2015; Benalcazar-Parra et al., 2017).

The most common method to predict labor induction

success is based on cervix assessment by the Bishop

score (Bishop, 1964). However, this measure is not

reliable and depends on the examiner subjectivity. In

fact, low accuracy of this predictor have been

70

Parra, C., Tendero, A., Ye-Lin, Y., Alberola-Rubio, J., Marin, A., Garcia-Casado, J. and Prats-Boluda, G.

Feasibility of Labor Induction Success Prediction based on Uterine Myoelectric Activity Spectral Analysis .

DOI: 10.5220/0006649400700077

In Proceedings of the 11th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2018) - Volume 4: BIOSIGNALS, pages 70-77

ISBN: 978-989-758-279-0

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

reported (AUC=0.39) (Bastani et al., 2011). Other

studies have considered other obstetrics variables

such as cervical length, maternal age, height, weight,

parity, and birth weight (Crane et al., 2004; Bastani et

al., 2011; Pitarello et al., 2013; Catherine Tolcher et

al., 2015; Prado et al., 2016) and showing an AUC

maximum of 0.69 for cervical length.

On the other hand, monitoring uterine contraction

is fundamental to assess maternal and fetal wellbeing

during the process, as well as, to estimate the labor

induction success. Intrauterine pressure is the most

accurate technique for monitoring uterine contractions.

However, it is an invasive technique and its application

requires membrane rupture (Vinken et al., 2009). The

most widely used method for non-invasively

monitoring uterine activity is to place a

tocodinamometer (TOCO) on women abdomen to

record changes of pressure in the abdominal contour

during uterine contractions. But they are uncomfor-

table, often inaccurate and depend on a subjective

interpretation by the examiner (Vinken et al., 2009).

Alternatively, electrohysterography (EHG) has

been proved to be a potentially useful technique for

non-invasively monitoring of uterine dynamics

obtaining better performance than TOCO (Alberola-

Rubio et al., 2013; Euliano et al., 2013; Benalcazar-

Parra et al., 2017). It consists of recording the

electrical activity of the uterus on the abdominal

surface using electrodes. At present, great efforts

have been made to differentiate between effective

contractions and non-effective contractions and

between term and preterm EHG records (Fele-Zorz et

al., 2008; Fergus et al., 2013). A shift of the energy

content toward higher frequencies as labor

approaches has been identified by literature (Marque

et al., 1986). Several spectral parameters have been

extracted from the power spectral density of the EHG

such as the deciles (D1-D9), which correspond to

frequencies below which it is contained 10-90% of

the total energy respectively (Alamedine et al., 2014),

and it has been reported its ability to distinguish

between pregnancy and labor contractions.

However, few efforts have been made to

characterize the uterine myoelectrical response to

labor induction drugs and to predict labor induction

outcome based on EHG recording (Tibor Toth, 2005;

Aviram et al., 2014; Benalcazar-Parra et al., 2017).

Therefore, the aim of this work was to determine the

feasibility of predicting different labor induction

outcomes, during the first 4 hours after labor

induction onset, by analyzing changes in the EHG

spectral characteristics as response of induction

drugs. Specifically, it was analyzed the time evolution

of deciles of the EHG-burst’s PSD.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Signal Acquisition

The study adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki and

was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital

Universitario y Politécnico La Fe (Valencia, Spain).

All subjects were informed of the nature of the study

and signed an informed consent form. Recording

sessions were carried out in healthy women with

singleton pregnancies and without risk who were

determined to undergo labor induction by medical

prescription. Specifically, 72 pregnant women with a

gestational age between 40 and 41 weeks were

enrolled in the study. The induction was carried out

by administration of two different types of drugs:

vaginal insertion of 25 μg misoprostol (Misofar, Bial,

Coronado, Portugal) with repeated doses every 4

hours up to a maximum of 3 doses (N=35) and 10 mg

of dinoprostone (Propess, Ferring, Germany) by

vaginal insertion (N=37). The following obstetrical

data was collected: maternal age, body mass index

(BMI), Bishop score and the labor induction outcome.

Patients were divided in 4 groups according to the

outcome of the delivery: G1: vaginal delivery within

24 hours after induction onset (N=26), G2: vaginal

delivery> 24 hours (N=26) after induction onset, G3:

cesarean section after achieving active phase of labor

(N=11), G4: cesarean section without achieving

active phase of labor (N=9).

Three different labor outcome scenarios were

studied:

• Scenario 1 (S1): Women achieving

active phase of labor (Successful group

S1GS= G1+G2+G3; N=63) vs women

non achieving active phase of labor,

(Failed group, S1GF=G4; N=9)

• Scenario 2 (S2): From women who

achieved active phase of labor, those

achieving vaginal delivery (Successful

group, S2GS=G1+G2; N=52) vs

cesarean section (Failed group

S2GF=G3; N=11)

• Scenario 3 (S3): Women achieving

vaginal delivery within 24 hours

(Successful group S3GS=G1; N=26) vs

other outcomes, (Failed group

(S3GF=G2+G3+G4; N=46)

TOCO and EHG were simultaneously acquired in

each recording session. The electrode arrangement

for the acquisition of EHG is shown in Figure 1: 2

electrodes were placed supraumbilically at each side

of the abdominal medial line with 8 cm of inter-

electrode distance corresponding to EHG monopolar

Feasibility of Labor Induction Success Prediction based on Uterine Myoelectric Activity Spectral Analysis

71

records (M1, M2), 1 reference electrode in the right

hip and 1 ground electrode in the left hip. The

recording time comprises 30 minutes corresponding

to recording of basal activity and 4 hour recording

from drug administration (induction onset). Details of

the recording protocol can be found in an previous

study (Benalcazar-Parra et al., 2017).

Figure 1: Surface electrodes arrangement for monopolar

EHG recordings (M1, M2).

2.2 EHG Signal Analysis

Since the EHG signal mainly distributes its energy in

the range of 0.1 - 4 Hz, a digital band pass filter was

performed to eliminate unwanted components. Then

EHG signal was down-sampled to a sample frequency

of 20 Hz to decrease the computational cost. After

signal pre-processing, the bipolar register was

obtained digitally as follows:

Bip = M2 - M1

(1)

Subsequently, from bipolar signal, EHG-bursts

associated to uterine contractions were manually

segmented using the same criteria as in a previous

study (Benalcazar-Parra et al., 2017). Next, in order

to characterize the EHG bursts, the deciles of the

power spectral density were obtained in the range of

(0.2-1Hz) since it has been reported that the main

uterine activity is distributed in this frequency range

(Marque et al., 1986; Garfield and Maner, 2007).

First, the Welch periodogram method was used to

calculate the power spectral density of each EHG-

burst with a window size of 60 seconds and 50%

overlap. Subsequently deciles were computed as

follows:

(2)

Where P is the power vector from the PSD and [D

j-1

,

Dj] is the frequency range associated to the decile D

j

with j=1…9.

To analyse the evolution of the EHG-bursts’

spectral parameters in response to labor induction

drugs, firstly the median values of the deciles

associated to the EHG-bursts present in consecutive

intervals of 30 minutes were worked out for each

patient. Then, for each decile and 30-minuteinterval,

the mean and standard deviation were calculated for

all patients of a group. Finally, a statistical analysis

was performed by the Mann–Whitney test (=0.05)

to determine if there were statistical differences

between the groups of each obstetrical scenario.

3 RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the obstetrical variables and the

labor induction outcome of the population under

study. For a total of 72 patients, 87.5% achieved

active phase of labor. However, only 72.2% reached

vaginal delivery and 27.8% ended up with a cesarean

section. This last include all cesarean sections:

women who succeed to achieve active phase of labor,

but due to other medical issues (loss of maternal-fetal

wellbeing or pelvic-fetal disproportion) underwent

cesarean section and those who did not reach active

phase of labor.

Table 1: Patients’ obstetrical and clinical variables. Mean

(std).

Obstetric variables

Mean ± std

Maternal age (years)

31.7 ± 4.6

BMI (kg/m

2

)

28.9 ± 4.1

Bishop

1.4 ± 0.7

Active phase of labor

63/72 (87.5%)

Vaginal delivery

52/72 (72.2%)

>24h

26/52 (50%)

<=24h

26/52 (50%)

Cesareans

20/72 (27.8%)

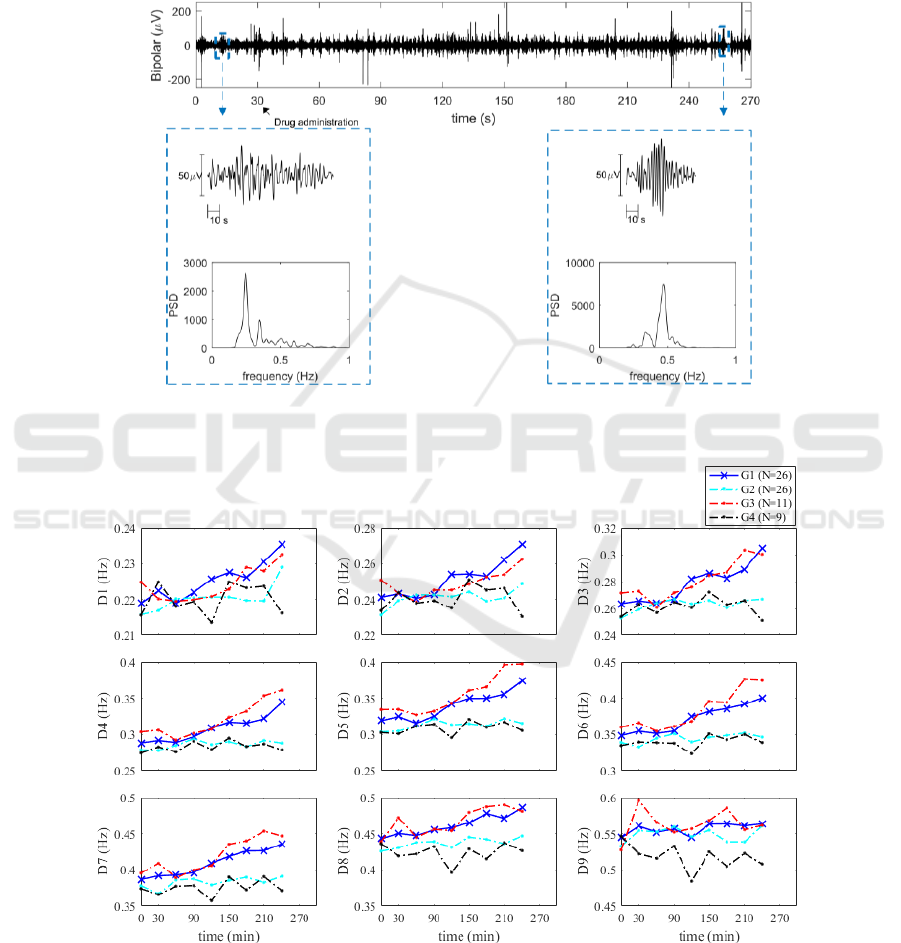

Figure 2 shows a representative EHG recording

from an induced woman who reached active phase of

labor and vaginal delivery within 24 hours after

induction onset. Comparing the characteristics of the

EHG-bursts recorded before drug administration

(basal period) and those presented at the last

recording hour, EHG-bursts after 4 hours from

induction onset were of higher amplitude, shorter

duration than those at basal period. Moreover the PSD

analysis revealed a shift of the energy content toward

BIOSIGNALS 2018 - 11th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

72

higher frequencies as labor induction progresses.

Figure 3 shows the temporal evolution of the

deciles’ mean values for the groups G1, G2, G3 and

G4. Increasing tendencies can be noticed in all deciles

for G1 and G3 groups except for D9. This reveals that

there is a clear shift toward higher frequencies for the

group of women that are closer to vaginal delivery

and for women delivering by a cesarean section but

achieving active phase of labor (G1 and G3

respectively). While for the group that is further away

from vaginal delivery (G2) and the group of women

that failed in reaching active phase of labor (G4),

there is not a clear tendency in any decile, remaining

almost constant throughout the recording session.

Figure 2: EHG recordings from a woman that reached active labor period and vaginal delivery within 24 hours from labor

induction onset.

Figure 3: Deciles’ temporal evolution for the groups: G1: vaginal delivery within 24 hours after induction onset, G2 vaginal

delivery> 24 hours after induction onset, G3: cesarean section after achieving active phase of labor, G4: cesarean section

without achieving active phase of labor.

Feasibility of Labor Induction Success Prediction based on Uterine Myoelectric Activity Spectral Analysis

73

In order to study the different situations derived

from labor induction, and to analyze the capacity of

the deciles derived from EHG bursts’ PSD to

discriminate between success and failure groups in

each scenario, statistical Mann-Whitney test was

performed for each scenario (Tables 2-4).

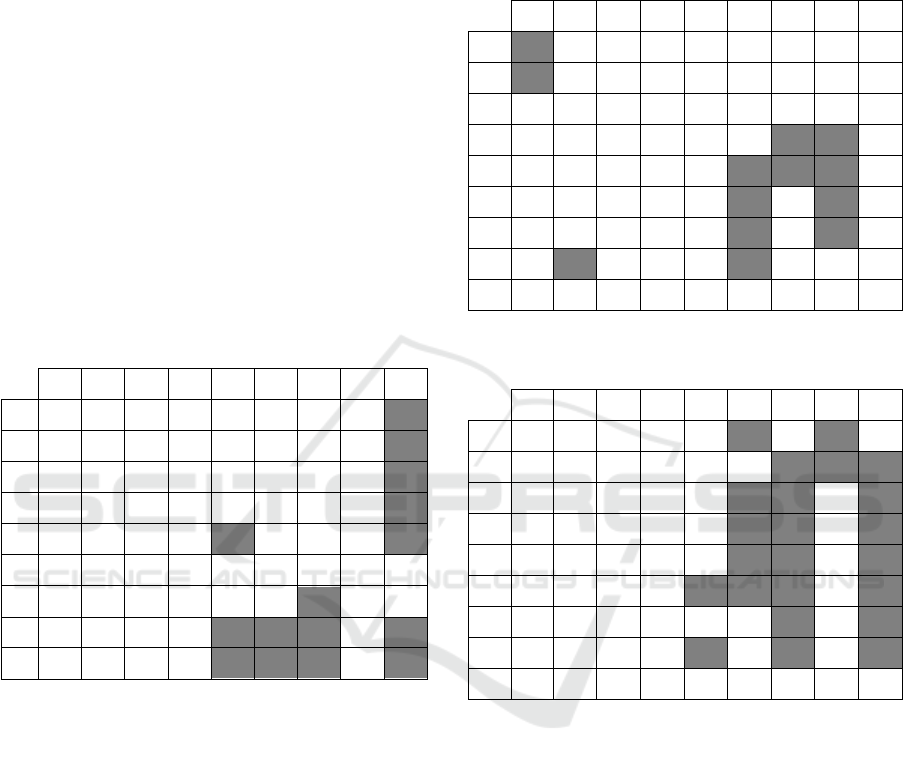

Table 2 shows the statistical significance for each

30-minute analysis interval when comparing the EHG

parameters of women that succeed in achieving active

phase of labor (S1GS) to those that failed (S1GF). It

can be noticed that all deciles show statistically

significant difference at least in one 30-minute

interval (generally the last) except for D6.

Outstanding results to discriminate between S1GS

and S1GF are found for D8 and D9, both showing

sustained statistical difference after 120 minutes from

drug administration to the last analysis interval

(except for 210’)

Table 2: Statistical differences in scenario 1 (S1GS vs

S1GF). Shaded cells represent p-values <0.05.

0'

30'

60'

90'

120'

150'

180'

210'

240'

D1

0.55

0.29

0.97

0.88

0.05

0.61

0.99

0.94

0.01

D2

0.58

0.51

0.70

0.97

0.11

0.65

0.94

0.77

0.01

D3

0.44

0.77

0.54

0.86

0.24

0.77

0.52

0.66

0.01

D4

0.23

0.78

0.34

0.74

0.14

0.52

0.28

0.31

0.04

D5

0.24

0.25

0.96

0.45

0.04

0.43

0.16

0.30

0.03

D6

0.40

0.80

0.77

0.21

0.06

0.34

0.16

0.32

0.14

D7

0.69

0.41

0.67

0.31

0.07

0.28

0.04

0.51

0.07

D8

0.84

0.20

0.29

0.38

0.01

0.04

0.01

0.25

0.05

D9

0.91

0.12

0.07

0.23

0.01

0.04

0.03

0.20

0.03

Table 3 displays the statistical significance for

each 30-minute analysis interval when comparing the

EHG parameters, from women who achieved active

phase of labor, those of women achieving vaginal

delivery vs those of women that underwent cesarean

section. For this scenario, deciles D3 and D9 are the

only ones that do not show statistical difference in any

analysis interval. The best decile to discriminate

between S2GS and S2GF was D5, showing statistical

differences in intervals 150’-210’.

Table 4 shows the statistical difference of the

EHG parameters of women that achieve vaginal

delivery within 24 hours after labor onset compared

to the rest of labor outcomes. All deciles show

statistical difference at least one analysis interval

except for D9. Deciles D2-D6 and D8 seem to be

potential predictors of the vaginal delivery within 24

hours, since they show statistical differences in at

least 3 analysis intervals, being the best result

obtained for D6.

Table 3: Statistical differences in scenario 2 (S2GS vs

S2GF). Shaded cells represent p-values <0.05.

0'

30'

60'

90'

120'

150'

180'

210'

240'

D1

0.02

0.75

0.85

0.99

0.80

0.99

0.18

0.30

0.95

D2

0.01

0.87

0.72

0.49

0.99

0.86

0.30

0.40

0.95

D3

0.06

0.39

0.62

0.36

0.57

0.41

0.06

0.07

0.97

D4

0.05

0.15

0.73

0.47

0.39

0.18

0.03

0.02

0.59

D5

0.07

0.23

0.54

0.47

0.22

0.03

0.05

0.01

0.55

D6

0.22

0.22

0.75

0.57

0.27

0.05

0.11

0.02

0.39

D7

0.39

0.05

0.95

0.54

0.32

0.02

0.13

0.02

0.55

D8

0.76

0.01

0.88

0.35

0.33

0.05

0.14

0.06

0.87

D9

0.49

0.09

0.93

0.95

0.50

0.53

0.11

0.88

0.82

Table 4: Statistical differences in scenario 3 (S3GS vs

S3GF). Shaded cells represent p-values <0.05.

0'

30'

60'

90'

120'

150'

180'

210'

240'

D1

0.86

0.40

0.55

0.80

0.06

0.03

0.16

0.04

0.07

D2

0.43

1.00

0.83

0.64

0.09

0.25

0.05

0.04

0.01

D3

0.23

0.90

0.76

0.77

0.10

0.03

0.03

0.15

0.01

D4

0.41

0.33

0.43

0.81

0.07

0.04

0.04

0.26

0.00

D5

0.15

0.10

0.98

0.71

0.07

0.04

0.02

0.32

0.01

D6

0.49

0.15

0.77

0.65

0.03

0.05

0.03

0.12

0.02

D7

0.77

0.15

0.80

0.55

0.06

0.13

0.03

0.08

0.03

D8

0.26

0.33

0.48

0.41

0.03

0.26

0.02

0.08

0.02

D9

0.39

0.98

0.75

0.67

0.59

0.34

0.20

0.14

0.14

4 DISCUSSION

In clinical practice, a large percentage of all deliveries

are performed through induction of labor, being one

of the most frequent procedures in obstetrics. In fact,

the number of labor inductions has increased

significantly in recent years (Hamilton et al., 2012).

However, not all inductions end in vaginal delivery,

associated with an increase in the rate of cesarean

sections. The latter may simply be due to the fact that

the uterus is not well prepared for delivery by

presenting an immature cervix or a myometrium

unable to achieve effective synchronous contractions

or any other condition that make vaginal delivery be

inviable (Cunningham et al., 2010). It would be a key

aspect to know, as soon as possible, the outcome of a

BIOSIGNALS 2018 - 11th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

74

labor induction so that clinicians may be able to better

plan deliveries, preventing maternal and fetal stress

which can appear in this long process.

Spectral parameters from EHG have been

extracted and used wideley in intention to predict

preterm labor (Buhimschi et al, 1997; Leman et al,

1999; Alamedine et al, 2013; Fergus et al., 2013;

Alamedine et al., 2014). Nonetheless, the

applicability of EHG during induction of labor or its

ability to predict the outcome to be obtained from

induction has not been thoroughly explored.

In this study, it was analyzed the response of

uterine muscle electrical activity to labor induction

drugs. The results of this work indicate that patients

from G1 and G3 experimented an evident shift of

their energy content toward higher frequencies

throughout the recording session (increasing

tendencies are seen in all deciles). This is consistent

with the literature which points out that agents for the

stimulation of uterine activity, act favoring the

increase of cell junctions (gap junction) and the ratio

of cells’ excitability (Garfield and Maner, 2007)

which is related with the presence of more intense

contractions and with higher frequency components.

Moreover, this increment is consistent with another

study in which was found that decil D8 experienced

an increment in its values from pregnancy to labor

(Alamedine et al., 2014).

In contrast, the group that did not reach active

phase of labor (G4) did not exhibit clear trends in any

decile, that is, no spectral displacement was observed

during the first four hours after labor induction onset.

Nevertheless, the same phenomenon was observed

for women that delivered in more than 24 hours after

induction onset. This result may suggest that more

recording time will be needed to observe the shift of

the EHG-Bursts spectral content towards higher

frequencies for women with a relatively slow

response to labor induction drugs.

Our work confirms the utility of decile parameters

to characterize the electrophysiological response of

the uterus to labor induction drugs, and points to the

possibility of predicting the different outcome of the

labor induction by analyzing the EHG-Bursts during

the first 4 hours after induction onset. D8 and D9

show statistical difference between women achieving

active phase of labor to those that failed after 120

minutes from labor induction onset to end of the

recording session except for the time interval 210’.

Then for women who achieved active phase of labor,

D5 could be useful, to discriminate between vaginal

deliveries and cesarean section in the time intervals

150’-210’. Finally, D2-D6 showed statistical

difference between vaginal deliveries within 24 hours

and the rest of women under study, being D6 the one

with best results and showing statistically significant

difference in the time intervals 120’-240’ (except for

210’). Moreover, the time required to observe

statistical significant differences in EHG spectral

parameters between women achieving active phase of

labor to those that failed (S1) is consistent with

pharmacokinetics studies: literature reported that the

time to reach sustained uterine dynamics was 106 and

127 minutes after misoprostol and dinoprostone

vaginal administration respectively (Yount and

Lassiter, 2013).

Although it has been shown that EHG spectral

parameters contain relevant information for

predicting labor induction outcomes, this study is not

exempt of limitations. First, a larger database is

needed to corroborate these results. Second, the

prediction of labor induction success remains a

challenge from the scientific-technical point of view.

Vaginal delivery> 24 h presents a similar trend to the

non-PAP group during the first 4 hours of recording,

which makes it necessary to extend the recording time

in order to be able to predict more accurately whether

a woman is going to reach active phase of labor or

not. On the other hand, the EHG record only contains

information of the myoelectric uterine activity, and

there are multiple causes, such as loss of maternal-

fetal wellbeing or pelvic-fetal disproportion, that

could lead to cesarean delivery that are not necessary

reflected in the EHG recording. In this sense, the use

of EHG recording together with other obstetric

parameters (bishop score, cervical length, maternal

age, birth weight, etc) could improve prediction

accuracy of induction success. In addition, the

application of advanced pattern identification

techniques such as neural networks and/or support

vector machines could be another key point for

developing new tools for predicting labor induction

success that could help obstetric clinicians in labor

management. .

5 CONCLUSION

To conclude, EHG can provide relevant information

about the uterine myoelectrical state through labor

induction. A clear shift of the EHG-Bursts energy

content toward higher frequencies was identified in

the temporal evolution of G1 (vaginal delivery within

24 hours after induction onset) and G3 (cesarean

section after achieving active phase of labor) groups

for all deciles. In contrast, non-remarkable changes in

the spectral characteristics of the EHG were seen for

G2 (vaginal delivery> 24 hours after induction onset)

Feasibility of Labor Induction Success Prediction based on Uterine Myoelectric Activity Spectral Analysis

75

and G4 (cesarean section without achieving active

phase of labor) during the first four hours after labor

onset. Moreover, deciles of the EHG-Bursts’ PSD are

potentially useful to discriminate between the

different outcomes of the labor induction, suggesting

the feasibility of EHG recording for predicting labor

induction success.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the the Ministry

of Economy and Competitiveness and the European

Regional Development Fund (DPI2015-68397-R).

REFERENCES

Alamedine, D. et al. (2014) ‘Selection algorithm for

parameters to characterize uterine EHG signals for the

detection of preterm labor’, Signal, Image and Video

Processing, 8(6), pp. 1169–1178. doi: 10.1007/s11760-

014-0655-2.

Alamedine, D., Khalil, M. and Marque, C. (2013)

‘Comparison of Different EHG Feature Selection

Methods for the Detection of Preterm Labor’,

Computational and Mathematical Methods in

Medicine, 2013, pp. 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/485684.

Alberola-Rubio, J. et al. (2013) ‘Comparison of non-

invasive electrohysterographic recording techniques for

monitoring uterine dynamics’, Medical Engineering

and Physics, 35, pp. 1736–1743. doi:

10.1016/j.medengphy.2013.07.008.

Aviram, A. et al. (2014) ‘Effect of Prostaglandin E2 on

Myometrial Electrical Activity in Women Undergoing

Induction of Labor’, J Perinatol, 31, pp. 413–418. doi:

10.1055/s-0033-1352486.

Baños, N. et al. (2015) ‘Definition of Failed Induction of

Labor and Its Predictive Factors: Two Unsolved Issues

of an Everyday Clinical Situation’, Fetal Diagn Ther,

38, pp. 161–169. doi: 10.1159/000433429.

Bastani, P. et al. (2011) ‘Transvaginal ultrasonography

compared with Bishop score for predicting cesarean

section after induction of labor’, International Journal

of Women’s Health, 3, pp. 277–280. doi:

10.2147/IJWH.S20387.

Benalcazar-Parra, C. et al. (2017) ‘Characterization of

Uterine Response to Misoprostol based on

Electrohysterogram’, in Proceedings of the 10th

International Joint Conference on Biomedical

Engineering Systems and Technologies. SCITEPRESS

- Science and Technology Publications, pp. 64–69. doi:

10.5220/0006146700640069.

Bishop, E. H. (1964) ‘Pelvic Scoring For Elective

Induction’, Obstetrics and gynecology, 24, pp. 266–8.

Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14199536

(Accessed: 6 June 2017).

Buhimschi, C., Boyle, M. B. and Garfield, R. E. (1997)

‘Electrical activity of the human uterus during

pregnancy as recorded from the abdominal surface’,

Obstetrics & Gynecology, 90(1), pp. 102–111. doi:

10.1016/S0029-7844(97)83837-9.

Catherine Tolcher, M. et al. (2015) ‘Predicting Cesarean

Delivery After Induction of Labor Among Nulliparous

Women at Term’, Obstet Gynecol, 126(5), pp. 1059–

1068. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001083.

Crane, J. M. G. et al. (2004) ‘Predictors of successful labor

induction with oral or vaginal misoprostol’, The

Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal

MedicineOnline) Journal, 15(5), pp. 319–323. doi:

10.1080/14767050410001702195.

Cunningham, F. G. et al. (2010) Williams Obstetrics. 23rd

edn. McGraw-Hill Professional.

Euliano, T. Y. et al. (2013) ‘Monitoring uterine activity

during labor: A comparison of 3 methods’, American

Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 208(1), p. 66.e1-

66.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.873.

Fele-Zorz, G. et al. (2008) ‘A comparison of various linear

and non-linear signal processing techniques to separate

uterine EMG records of term and pre-term delivery

groups’, Med Biol Eng Comput, 46, pp. 911–922. doi:

10.1007/s11517-008-0350-y.

Fergus, P. et al. (2013) ‘Prediction of Preterm Deliveries

from EHG Signals Using Machine Learning’, PLoS

ONE, 8(10). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077154.

Filho, O. B. M., Albuquerque, R. M. and Cecatti, J. G.

(2010) ‘A randomized controlled trial comparing

vaginal misoprostol versus Foley catheter plus oxytocin

for labor induction’, Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica

Scandinavica. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 89(8), pp.

1045–1052. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.499447.

Garcia-Simon, R. et al. (2016) ‘Economic implications of

labor induction’, International Journal of Gynecology

& Obstetrics, 133(1), pp. 112–115. doi:

10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.08.022.

Garfield, R. E. and Maner, W. L. (2007) ‘Physiology and

electrical activity of uterine contractions’, Seminars in

Cell & Developmental Biology, 18, pp. 289–295. doi:

10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.05.004.

Gilstrop, M. and Sciscione, A. (2015) ‘Induction of labor—

Pharmacology methods’, Seminars in Perinatology, 39,

pp. 463–465. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.07.009.

Hamilton, B. et al. (2012) Births: Final data for 2012.

Hyattsville. Available at: www.cdc.gov/

nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr62/nvsr62 09.pdf.

Indraccolo, U., Scutiero, G. and Greco, P. (2016)

‘Sonographic Cervical Shortening after Labor

Induction is a Predictor of Vaginal Delivery’, Revista

Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. Federação

Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia,

38(12), pp. 585–588. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1597629.

Leman, H., Marque, C. and Gondry, J. (1999) ‘Use of the

electrohysterogram signal for characterization of

contractions during pregnancy’, IEEE Transactions on

BIOSIGNALS 2018 - 11th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

76

Biomedical Engineering, 46(10), pp. 1222–1229. doi:

10.1109/10.790499.

Marque, C. et al. (1986) ‘Uterine EHG Processing for

Obstetrical Monitorng’, IEEE Transactions on

Biomedical Engineering, BME-33(12), pp. 1182–1187.

doi: 10.1109/TBME.1986.325698.

Pandis, G. K. et al. (2001) ‘Preinduction sonographic

measurement of cervical length in the prediction of

successful induction of labor’, Ultrasound in Obstetrics

and Gynecology. Blackwell Science Ltd., 18(6), pp.

623–628. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7692.2001.00580.x.

Pitarello, P. da R. P. et al. (2013) ‘Prediction of successful

labor induction using transvaginal sonographic cervical

measurements’, Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. Wiley

Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company, 41(2),

pp. 76–83. doi: 10.1002/jcu.21929.

Prado, C. A. de C. et al. (2016) ‘Predicting success of labor

induction in singleton term pregnancies by combining

maternal and ultrasound variables.’, The journal of

maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official

journal of the European Association of Perinatal

Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania

Perinatal Societies, the International Society of

Perinatal Obstetricians, pp. 1–35. doi:

10.3109/14767058.2015.1135124.

Seyb, S. T. et al. (1999) ‘Risk of cesarean delivery with

elective induction of labor at term in nulliparous

women.’, Obstetrics and gynecology, 94(4), pp. 600–7.

Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10511367

(Accessed: 15 September 2016).

Tibor Toth (2005) ‘Transcutaneous Electromyography of

Uterus in Prediction of Labor Outcome Induced by

Oxytocine and Prostaglandine Shapes’, Gynaecologia

et perinatologia: journal for gynaecology,

perinatology, reproductive medicine and ultrasonic

diagnostics, 14(2), pp. 75–76.

Vinken, M. P. G. C. et al. (2009) ‘Accuracy of frequency-

related parameters of the electrohysterogram for

predicting preterm delivery: a review of the literature.’,

Obstetrical & gynecological survey, 64(8), pp. 529–41.

doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181a8c6b1.

Ware, V. and Raynor, B. D. (2000) ‘Transvaginal

ultrasonographic cervical measurement as a predictor

of successful labor induction’, American Journal of

Obstetrics and Gynecology, 182(5), pp. 1030–1032.

doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105399.

Yount, S. M. and Lassiter, N. (2013) ‘The Pharmacology of

Prostaglandins for Induction of Labor’, Journal of

Midwifery and Women’s Health, 58(2), pp. 133–144.

doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12022.

Feasibility of Labor Induction Success Prediction based on Uterine Myoelectric Activity Spectral Analysis

77