What is the Trigger of Migration Trends in Asia Pacific Region?

Elisabeth K. Yomkondo and Maria M. Niis

Universitas Airlangga

Keywords: Immigrants, trafficking, policy

Abstract: This study explains the elements that trigger migration trends in Asia Pacific. migrants from all of the

nations in the regions hold key role as development actors assist in boosting GDP of their host country,

while also support the family and society in their home countries. Migration will become the engine of

development and growth which are getting higher in this region since the interconnectivity between the

countries is also increased, as well as the demography inequality. The challenge of environment will also

increase pressure to jobs and economic growth will create new opportunities in all over the region. Along

January-August 2017, National Agency for Placement and Protection of Indonesian Workers (BNP2TKI)

has succeeded in placing 148.285 labor force or immigrants to several Countries in Asia Pacific, America,

Middle East, and Europe. The problem is that in some point the mobilization of labor force or migrants tend

to not according to procedures, so that leads to human trafficking problems which become national security

issue. On the other hand, there are also problems regarding the policy, permission, and procedure in

Indonesia government since there are a lot of findings regarding illegal labors. Thus it becomes one of the

concerns of Head of Economist of World Bank towards East Asia region since if the permissions and

procedures can be renewed then Indonesia as the migrants’ sender will receive economic benefits by

sending migration abroad. The issue faced by Indonesia was analyzed by using national security concept

and theory of securitization

1 INTRODUCTION

International migration is a global phenomenon

which can open opportunities for development as

well as challenges for governments. More than 200

million people live out of their home Country or

their nation. Migrations affect almost all of the

aspects of the nation whether it is their home

countries, transit countries, or host countries.

Migrant workers are humans who also have their

own rights which must be fulfilled. Since they do

not possess legal protection in the country where

they are migrating to, international migrant workers

can be vulnerable towards harassment and

exploitation. Legal protection and other kind of

protections must be conducted as assurance for the

fulfillment of labor rights and decent works for

migrant workers. This is due to the view of the

migrants as a group of people who can be exploited

and sacrificed, as cheap labor force, fragile, and

flexible, as well as willing to work in 3-D, dirty,

dangerous, and degrading environment, whereas the

host country is not willing and / or does not want to

accept them. As a result, the rights of migrant

workers are easily abused or abandoned. On the

other hand, migrant workers are contributing to the

development and economic and social welfare of

their home as well as host country. The rights of the

migrants which are violated in a society will

contribute to social disintegration and the decline of

respect for the law. For example, violation and

exploitation towards the migrant workers will

prevent them to obtain decent job and income, which

leads to the reduction for their contribution to the

local society as well as the remittances they may

give to their home countries. Conflict of interest

between economic pressure to exploit the migrants

and the necessity to protect them forces the

government to manage this condition by formulating

and implementing policy carefully and

comprehensively.

Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistic (BPS)

noted the number of poor population (population

with monthly per capita expenditure under the line

of poverty) in Indonesia in March 2015 reached

28.59 million people or 11.22%. The high number of

this population coupled with the low education level

makes a lot of Indonesian citizens especially people

Yomkondo, E. and Niis, M.

What is the Trigger of Migration Trends in Asia Pacific Region?.

DOI: 10.5220/0010275200002309

In Proceedings of Airlangga Conference on International Relations (ACIR 2018) - Politics, Economy, and Security in Changing Indo-Pacific Region, pages 211-218

ISBN: 978-989-758-493-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

211

who live in rural area lose in the work competition

to urgently need a decent job with purpose of

improving their family economy. In order to handle

those problems, Indonesian citizens choose to be

Indonesian Migrant Workers (TKI). Becoming a

TKI is one of the shortcuts to find job faster and

achieve higher salary rather than having the same

job in the country. A lot of Indonesians think that

being a migrant worker abroad is better than

becoming a farmer or laborer in Indonesia.

Indonesian Migrant Workers is divided into two

groups. The first group is formal TKI who work in

legal status whether it is from the government or

private. Meanwhile, the second group is the non-

formal TKI who work in individual level such as

housekeeper (PLRT), baby sitter, elderly nurse,

driver or gardener.

2 HISTORY OF MIGRATION

INDO PACIFIC

In the 1990s, international migration is occurring on

an unprecedented scale, involving a wide cross

section of populations and taking on a greater

variety of forms than any time in history. This is

nowhere truer than in the Asian region where rapid

economic growth, inter-country contrasts in the

extent of labor surplus or shortage the transport and

communication revolution and the globalisation

tendencies business activity have seen a burgeoning

of international population flows. Important (and

increasing) element in these movements has been

that of undocumented or illegal migrants. However,

our knowledge of international population

movements within Asia remains limited. Not only is

there uncertainty regarding the underlying causes

and consequences of this movement, but in many

cases the scale and composition of flows is not

known. This of course especially applies to the

burgeoning illegal movement.

It is important to realise that contemporary large-

scale movement from Indonesia Malaysia has strong

historical precedents. Although reports of movement

of Javanese workers to Malaysia go back five

centuries and evidence of movements between

Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula even further, the

movement particularly gained momentum during the

colonial period, especially in the late nineteenth

century. Temporary labor migration was an

important element whereby the resources of the

Netherlands East Indies were exploited by the Dutch

(Hugo, 1982). There were three major types of such

movement: forced migrations to work on

plantations, roads, etc. in which the potential

migrant was given little or no choice; "contract

coolie" migrations in which workers were recruited

to work, usually on a plantation, for a given period

(penal sanctions were applied if the conditions of the

contract were broken); spontaneous migration

whereby the migrant sought work temporarily away

from his/her homeplace either on their own

initiative or through that of friends only or family.

Each of these types of movement has both an

internal and an international component. With

respect to forced movement, besides virtual slavery

in early colonial years, the Romusha forced labor

saw the Japanese occupation forces in the 1940s

transporting Indonesians to work on railway and

other construction projects in Thailand, Burma and

elsewhere. Contract labor gradually came to replace

slavery, corvée and labor in lieu of taxes after 1870.

Recruiters were common in many areas of Java in

colonial times (Hugo, 1975) and significant numbers

of contract workers were sent abroad especially to

the Malay Peninsula (Jackson, 1961) and Surinam,

but also to New Caledonia, Siam (Thailand), British

North Borneo (Sabah), Sarawak, Cochin China

(Vietnam) and even Australia. In the early twentieth

century, the colonial government attempted to stop

the activities of companies recruiting labor for

foreign countries except where specially licensed,

although contract labor recruitment within the

country continued. Accordingly, as a result of

contract coolie movements, by 1930 there were

89,735 Java-born persons living in Malaya (Bahrin,

1967:280) and 170,000 ethnic Javanese residents

(Volkstelling, 1936, VIII:45). There were also 5,237

Java-born persons in British North Borneo (now

Sabah) in 1922 (Scheltema, 1926:874). In addition

to the contract coolie movements of the Java-born,

there were also significant, largely spontaneous

labor movements of Minangkabau, Batak, Bugis,

Banjarese and Bawean migrants to Malaya from

other islands of the Netherlands East Indies.

Labor movements from the Netherlands East

Indies (NEI) to Malaya increased in the 1930s

(Bahrin, 1967) and the major patterns are depicted in

Figure 1. The diagram also shows the distribution of

the birthplaces of Indonesian-born residents of

Malaya recorded at the 1947 Malaya census. The

number of Java-born recorded was 189,450 (an

increase of 111 per cent over the 1930 figure). There

were also 62,400 Banjarese from South Kalimantan

and 26,300 Sumatrans, predominantly Minangkabau,

from West Sumatra and Mandaling Batak from

North Sumatra. The Minangkabau movement was a

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

212

longstanding one with many settling in the Negri

Sembilan area (Hadi, 1981). There were also 20,400

Bawean-born and 7,000 Celebes-born people

identified (Bahrin, 1965:53). These figures of course

only apply to Peninsular Malaysia and it should be

mentioned that there was significant movement from

the NEI into British North Borneo and, to a lesser

extent, Sarawak. The so called "Boyanese" group

presents an interesting case. They come from the

tiny island of Bawean which currently has a

population of around 66,000 and is frequently

known as the "Island of Women". In almost all

households on the island, the male head or a son is

away working in Malaysia or Singapore (Anon.,

1982). This movement has become a rite de passage

in the society for young men to the extent that a

woman is reported to have sought to divorce her

husband on the grounds that he isn't really an adult

man because he has never gone merantau (migrated

temporarily) (Subarkah, Marsidi and Fadjari,

1986:2). This migration is said to date back to links

established with Palembang in the early seventeenth

century when the Sultan of Bawean was converted

to Islam by a missionary from the southern part of

Sumatra. In any case they were recorded as a distinct

group in the Singapore census of 1894 and had

increased to 22,000 by the 1957 census

(Vredenbregt, 1964). They also appear to have

established a Kampung Boyan in Saigon (now Ho

Chi Minh city), Vietnam at the end of the nineteenth

century (Anon., 1982:62). To many (perhaps the

majority) of Bawean men, the Malaya Peninsula or

Singapore has become a tanah air kedua (Anon.,

1982:62) or second native country.

This is admittedly a somewhat extreme case but

it does indicate the extent of migratory links

between parts of Indonesia and Malaysia-Singapore

which have existed for a long period of time. This

can be further underlined by the fact that in 1982

when the Malaysian Deputy Prime Minister (Datuk

Musa Hitam) made an official visit to Jakarta for

negotiations regarding a "Supply of Workers

Agreement" with Indonesia, he mentioned that his

grandmother was a Bugis born in Ujung Pandang,

South Sulawesi (Anon., 1982:64). The important

point here is that there are long-standing and strong

social networks linking Malaysia and Indonesia. The

political boundaries separating the two nations are a

function of colonisation and separate peoples who

share the same culture, language and religion. These

historical linkages and cultural homogeneity have

played an important role in facilitating population

movement from Indonesia to Malaysia. During

World War II and early post-Independence years,

the flow of labor migrants from Indonesia to

Malaysia subsided, especially in the years of

Confrontation. However, beginning in the early

1970s, shortages of labor in the plantation,

agricultural and construction sectors saw the

beginnings of illegal flows of Indonesians into both

Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia (Dorall and

Paramasivam, 1992:13).

3 ASIA PACIFIC MIGRATION IN

GLOBAL PRESPECTIVE

This section puts migration in the Asia-Pacific

region in a global context and explores the major

reasons why migration in the region is likely to

increase before it decreases. The major points

include; 1. Asia is different in both perception and

reality. One perception is that, just as some Asian

countries managed to achieve very rapid economic

growth, some may succeed in managing labor

migration more successfully than governments in

other parts of the world; 2. Policies of migrant-

receiving countries vary significantly, with the

triangle of policies framed by Singapore’s welcome

the skilled and rotate the low-skilled, Japan’s largely

closed doors to low-skilled foreign workers, and the

dependence of Gulf oil exporters on migrants to fill

90 percent of private-sector jobs; 3. Policies of

migrant-sending countries are more similar, with

many governments aiming to send more skilled

workers to destinations inside and outside Asia and

to measure the development impacts of migration

using the single indicator of remittances.

The Asia-Pacific region, home to almost 60

percent of the world’s people, is unusual in dealing

with migration in three major respects. First, there is

a widespread sense inside and outside the region that

Asia is different. There are many reasons, including

the Asian economic miracle that catapulted several

countries from poorer to richer in a relatively short

time (World Bank, 1993). This economic success

may encourage some Asian leaders to believe that

they can achieve another success in managing

internal and international labor migration to achieve

goals that include protecting migrants and local

workers, enhancing cooperation between

governments in labor-sending and –receiving areas

to better manage migration, and ensuring that

migration promotes development in labor-sending

areas.

Second, there is more diversity in national labor

migration policies than in national economic

What is the Trigger of Migration Trends in Asia Pacific Region?

213

policies. The policy extremes can be approximated

by a triangle. Singapore lies at one corner

welcoming professionals to settle with their families

while rotating less-skilled foreign workers in and out

of the country. Japan lies at another corner, allowing

but not recruiting foreign professionals and

preferring ethnic Japanese from Latin America as

well as foreign trainees, students, and unauthorized

workers to guest workers with full labor market

rights. The Gulf Cooperation Council countries

represent a third corner, relying on migrants for over

90 percent of private-sector workers, requiring

migrants to have citizen-sponsors, and recently

announcing policies to cooperate with migrant-

sending countries to assure returns. The contrast

between the similar investment-intensive and export-

led economic policies of East and Southeast Asian

nations, and the dis-similar labor migration policies,

is striking.

Third, there appears to be convergence in the

migration policies of labor-sending governments in

the region. Most want to send more workers abroad,

to increase the share of skilled workers among

migrants, and to diversify the destinations of

migrants to include more European and North

American destinations. To achieve these marketing,

up skilling, and diversification goals, many Asian

governments have established ministries or agencies

to promote and protect migrants, with promotion

accomplished by ministerial visits and protection via

regulation of private-sector recruiters and pre-

departure reviews of the contracts they offer to

migrants. The evolving migrant promotion and

protection infrastructure often assumes that

development is a natural or inevitable outgrowth of

sending more workers abroad, so that remittances

can serve as the major indicator of migration’s

development impacts. This may not be true.

4 WHY PEOPLE MIGRATE

International migration is usually a carefully

considered individual or family decision. The major

reasons to migrate to another country can be

grouped into two categories: economic and

noneconomic, while the factors that encourage a

migrant to actually cross borders fall into three

categories: demand-pull, supply-push, and networks.

An economic migrant may be encouraged to move

by employer recruitment of guest workers, demand-

pull, while migrants crossing borders for economic

reasons may be moving to escape unemployment or

low wages, supply push factors.

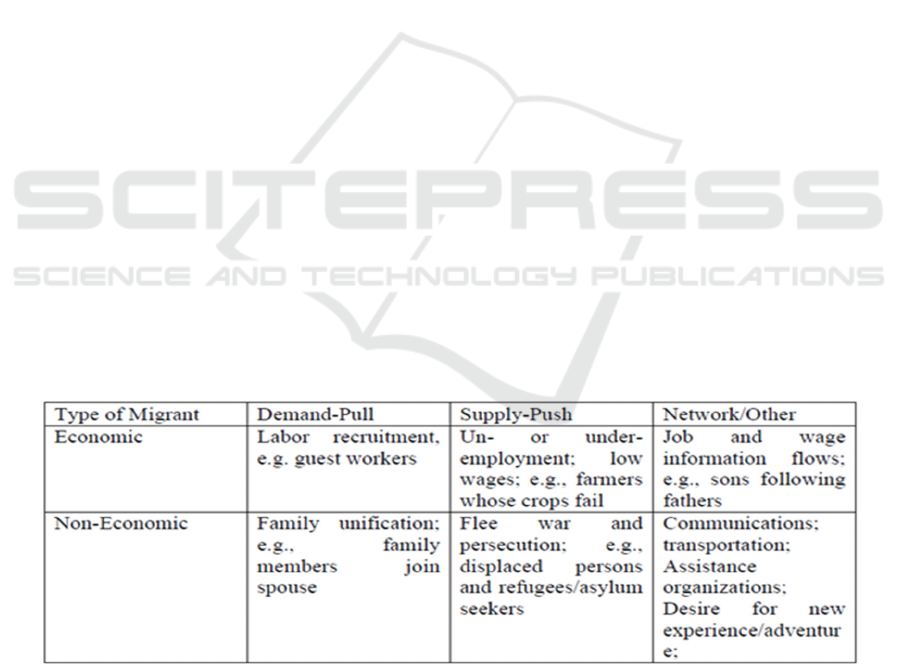

These factors are listed in the table below. A

worker in rural Indonesia may decide to migrate to

Malaysia because a friend or relative tells him of a

job, highlighting the availability of higher wage jobs

as a demand-pull factor. The worker may not have a

regular job at home or face debts from a family

member’s medical emergency, examples of supply-

push factors that encourage emigration. Networks

encompass everything from moneylenders who

provide the funds needed to pay a smuggler to

employers or friends and relatives at the destination

who help migrants to find jobs and places to live

Table 1: Factors Influencing Migrations, Factors Encouraging an Individual to Migrate

Demand-pull, supply-push, and network factors

rarely have equal weights in an individual migration

decision, and their weights can change over time.

Generally, demand-pull and supply push factors are

strongest at the beginnings of a migration flow, and

network factors become more important as

migration streams mature. The first migrant workers

are often recruited by employers, and their presence

is approved or tolerated by governments. The

demonstration effect of some migrants returning to

their areas of origin with savings can prompt more

people to seek foreign jobs. Network factors ranging

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

214

from friends and relatives settled abroad to the

expectation that especially young men and women

are expected to seek opportunity abroad can sustain

labor migration between poorer and richer areas

within and between countries.

5 MIGRANT SECURITY,

PERMISSIONS, AND

PROCEDURE THEORY

SCHEME

Indonesian migrant workers or basically all the

migrants help delivering dividend to the country.

TKI and immigrants indirectly possess important

role towards Indonesian economic development.

However, sometimes they are receiving problems

when they are working abroad so that the nation is

obliged to protect all of its citizens both inside and

outside the country. Actually there are already many

efforts which have been done by the Indonesian

government in reducing the number violence and

other violations which afflict the TKI and

immigrants. Those policies came up in several

governmental policies which were written in the

Constitution, government regulations, and other

ministerial regulations. However, even though there

are a lot of policies issued by Indonesian

governments in protecting Indonesian Migrant

Workers, the implementations of the protection

which were created are not able to protect the

Indonesian Migrant Workers whether in the pre

placement, placement, and the after placement stage.

Regarding the human security terminology,

Alberth and Carlsson (2009:23-24) collaborated it

with the human security through narrow human

security approach (human security in narrow

meaning) and broad human security (human security

in broad meaning). Narrow human security is related

to the actions which include the absence of

individual/personal threat (personal violence), and

consequently affect the absence of structural

violence threats. These two threats’ criteria actually

fulfill the primary category and inclusion criteria

regarding the ownership of emancipatory power.

Both of the absences of personal and structural

violence threat are the main power of emancipatory

concept. Broad human security should be consistent

to the critical security study. Therefore, critical

security study should be related to human security in

policy-making.

Security threats towards humans are becoming

significant to be the object of Security Studies which

are free from nation-state security dichotomy

through the field of traditional security (military)

and non-traditional security (non-military). Thus, the

factors of human freedom from various threats and

pressures, either militaristic or non-militaristic, are

the shifting form of Security Studies object which is

reflecting the shift of armed conflict nowadays.

Threats towards the damage of human security

existence is becoming wide open when referring to

United Nation’s Millennium Declaration and the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). In order

to assure human security in the MDGs framework,

then the goals to be built are (www.unocha.org,

2014: 2-3):

1. Protecting humans from crime conflicts

2. Protecting and empowering humans/citizens

related to migrations caused by conflict/war or

crime against human rights

3. Protecting and empowering humans related to

post-conflict conditions.

4. Economy security – related to the abolishment of

poverty, improvement of economic level and

social welfare.

5. Ensuring health for human security – spread of

disease and poverty threats as the impacts from

conflict; and

6. Improving knowledge, skill and value for human

security: providing basic education facility and

public information related to those three things

which relevant to the forms of crime resulted

from conflicts.

The focus shift in the study of traditional security

in becoming non-traditional security is actually

transforming a new form of war in each actor which

poses threats towards human security existence.

Attention towards human security has become one

kind of attention regarding the importance of global

security which has been generalized into six human

security outputs according to United Nations

Development Programs (UNDP). New kind of war

or future war will be more triggered by the six

purposes of human security.

In 2003 to 2005, Saudi Arabia was the most

favorite destination followed by Malaysia. In this

period there was a change in the third most favorite

destination which used to be Kuwait in 2003-2004

but then became the fifth most favorite after Taiwan

became the third most favorite and Singapore

became the fourth most favorite. In 2006, Saudi

Arabia still became the most favorite destination by

the majority of Indonesian job seekers but at Asia-

Pacific region in 2007, Malaysia became the most

favorite destination followed by Taiwan and Hong

Kong. Meanwhile, there are a lot of authors who

What is the Trigger of Migration Trends in Asia Pacific Region?

215

argued about the reason why the migrants chose

Malaysia as their most favorite destination. The

main reason for that is related to distance followed

by the cultural aspects which have many similarities.

Several studies showed that there were a significant

number of undocumented migrants especially the

ones going to Malaysia. These migrant workers were

going through two main routes; they are East Java-

North and South Sumatera to Malaysia Peninsular

and Flores-South Sulawesi to Sabah

(www.unesco.org/most/amprnwp8.htm). In the

process of the TKI/immigrants undocumented

delivery, there were several actors which were

allowing this to happen such as the brokers

syndicate, labor force recruiters, and taikong

(helmsman). Their involvement brought several

consequences such as the more expensive fees which

were paid by the workers and minimal protection for

them. There are a lot of cases which indicate that the

most problems faced by the migrant workers are

because of the departure done by this method.

There are around 6 million Indonesian citizens

who are currently abroad, where 80% of them are

Indonesian Migrant Workers. The majority of those

TKI are the people who work in non-formal sectors

or domestic workers. Those TKI are spreading into

160 countries and it is estimated that there are 1.2

million TKI who are illegal or the TKI who depart to

other countries via illegal method. The majority of

TKI who work in non-formal sectors is reflecting the

low-skill level which those TKI possess. The

majority of those TKI are also women who only

have junior high school or even elementary school

background. According to the Research Center for

the Development and Information of National

Agency for Placement and Protection of Indonesian

Migrant Workers (BNP2TKI), there are 351,639

TKI who have only junior high or even elementary

school background from the total of 521,168 TKI in

2013. The levels of education which the TKI possess

were also in line with the majority of their own

professions as housemaid more than any other

professions. There were 168.318 TKI whose

profession were housemaid in 2013, showing an

increase of the number in 20120 which was 164.981.

The limitation of education these TKI possessed

caused this group of workers to be more vulnerable

against issues that may happen to them, especially

the ones who work in domestic worker sectors.

The countries which have become the most

favorite destinations for Indonesian Migrant

Workers in 2012 were Malaysia with 1.9 million

people, followed by Saudi Arabia with 1.1 million

people, and Hong Kong with 189 thousand people.

Saudi Arabia became the second most favorite

destination because of religious reason since Saudi

Arabia was viewed as home for Muslims, thus

encouraging the TKI to choose Saudi Arabia while

at the same time the Muslims could also visit the

Kaaba to make Kaaba pilgrimage. While Malaysia

became the biggest TKI receiver because of the

geographical factor where Indonesia is directly

bordered with Malaysia and some of the citizens are

from Melayu Race with similar language. The

income that the TKI generated poses significant

impact to Indonesian government through

remittance. In 2013, the total of Indonesian

remittances from its TKI reached 88 Trillion rupiah.

Malaysia and Saudi Arabia are two dominant

countries who contribute in remittance more than

any other countries which become the destinations

for the TKI. TKI holds important role which aimed

to improve their families in Indonesia while being

vulnerable against the risks that may happen to them

anytime and anywhere. Working abroad by

becoming TKI is not without risks and obstacles.

Instead, the risks are far greater than working in

their own country. A lot of Indonesian Migrant

Workers especially the ones who work in informal

sectors to become victims in various criminal and

violent activities such as overwork, unpaid salary,

even violence that poses threat to their own lives. As

Indonesian President, Joko Widodo has set three

diplomacy priorities i.e. by maintaining Indonesia

sovereignty, improving the protection of the citizens

and Indonesian legal entities, and increasing

economic diplomacy. The President has placed the

citizen’s protection issue as Indonesia’s priority

agenda which means Indonesian foreign politic must

be able to give protection and safety for citizens and

legal entities of Indonesia in other countries.

According to VOA Indonesia (2014), Indonesia

President Joko Widodo has recently issued

presidential instruction regarding repatriation for the

problematic and undocumented TKI in several

countries. Since there were a lot of problematic and

undocumented TKI who were working in Malaysia,

the government chose this neighbor country as the

first country where the repatriation conducted. Up

until now the government has succeeded in

repatriating 703 problematic TKI from the estimated

total of 1428 people. They were carried gradually by

using five Hercules aircraft owned by Indonesian

National Air force. The chief of BNP2TKI Nusron

Wahid stated that the government is extremely

serious in solving the TKI issues.

Protection towards Indonesian Migrant Workers

(TKI) is basically the government’s responsibility.

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

216

However, this task is specifically handled by

Ministry of Labor and Transmigration together with

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Due to the complicated

process and the number of requirements, the

government then attempted to manage this issue by

creating BNP2TKI in order to help the protection

issue faced by the TKI based on Law No. 39 of 2004

which was regulated by Presidential Decree No. 81

of 2006. This led to the formation of three National

bodies which relate and intersect to each other

regarding the Indonesian Migrant Workers’

protection namely Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

Ministry of Labor and Transmigration, and National

Agency for Placement and Protection of Indonesian

Migrant Workers (BNP2TKI). Even though

according to one of BNP2TKI staffs who work in

protection deputy field there are actually 13

stakeholders related to the TKI protection such as

National Police, Ministry of Law and Human Rights

and other ministries, the most related bodies in

handling this issue are the BNP2TKI, Ministry of

Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Labor and

Transmigration.

6 DISCUSSION

As discussed above, the number of Indonesian

migrants abroad has been increasing recently and the

Indonesian Government has paid increased attention

to the labour migration process and how Indonesian

labour migrants are recruited, deployed and treated

in the destination countries. As a result, a number of

public policies have been enacted to better manage

the migration of Indonesian labour migrants. Broad

public interest in cases of mass deportation of

Indonesian labour migrants from Malaysia has also

caused civil society to put pressure on the

Government of Indonesia to strengthen legislation

that protects Indonesian labour migrants.

Economic reasons drive the majority of

Indonesian labour migrants to migrate abroad, to

improve the economic status of themselves and their

families. High levels of unemployment and

underemployment in Indonesia push many

individuals to look for jobs outside their area of

origin and many may decide to go abroad after

hearing about the availability of jobs from

recruitment agents and social networks and the

higher salaries on oer abroad in countries such as

Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong SAR, Kuwait,

Singapore and the United Arab Emirates. Many

individuals, especially women, see migration abroad

as the only way out of poverty for them and their

families. Most workers therefore migrate with the

intention of working abroad for only a limited period

of time in order to save enough money to purchase a

house, open a business or send their children or

relatives to school. Although labour migration from

Indonesia is characterized as temporary because few

migrants leave with the intention of settling in the

destination country, they generally do not have the

opportunity to stay even if they change their mind.

Nevertheless, due to the high costs often associated

with securing overseas employment, temporary

labour migration often turns into a stay that is longer

than expected and may last several years.

7 CONCLUSION

In the end, all of those questions will never give

ontological positioning answer in line with the

dynamics shifting of security issues variant. This

indicates that when it is reviewed as a security

concept, then human security produces various

interpretations that can be viewed from several

points of view of power interest and order whether

the interest is conducted by state actor, non-state

actor institution, or even in individual level. In that

sense, then human security today which was resulted

from the shift of Post-Cold War security issue is

dominated by non-state actors.

The lack of protection towards migrant workers

is because of three main factors. Those main factors

are the fragility of infrastructure of TKI protection in

other countries, the overlapping policies among the

involved stakeholders, and the legal protection

policy which is still reactive. The involved

stakeholders’ overlapping policies in this context are

the policies created by BNP2TKI, Ministry of

Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Labor and

Transmigration. This factor is reinforced by the

argument which stated that there are overlapping

laws. The second argument which reinforced the

second factor is the law related to tasks and

responsibility which are not professional yet. The

third factor which stated the reason why the migrant

workers’ protection is still reactive is due to the

reactive nature of the law. The government until

today is just solving the already-happening problems

while not totally trying to solve the source of the

problem itself.

What is the Trigger of Migration Trends in Asia Pacific Region?

217

REFERENCES

Journal

Graeme Hugo . Indonesian Labour Migration to Malaysia:

Trends and Policy Implications. Southeast Asian

Journal of Social Science. Journal Jstor. Vol.2, No.1

1993.

Hidayat Rizal. Keamanan Manusia Dalam Perspektif Studi

Keamanan Kritis Terkait Perang Intra-Negara. Journal

of International Studies. Vol.2, No.1 2017

Arry Bainus dan Junita. Editorial; Keamanan

Internasional. Journal of International Studies. Vol.2,

No.1 2017

Martin,Philip. Migration in the Asia-Pacifc Region:

Trends, factors, impacts. Munich Personal RePEc

Archive. UNDP Research Paper 2009.

Sejati, P. Satryo. Perlindungan Tenaga Kerja Indonesia di

Luar Negeri. Journal of Muhammadiyah University of

Yogyakarta, 2015.

Sukamdi. Memahami Migrasi Pekerja Indonesia ke Luar

Negeri. University of Gadjah Mada, 2007. [artikel ini

adalah artikel revisi dari makalah dalam seminar

Launching State of World Population, 2006]

Internet

VOA Indonesia, Pemerintahan Jokowi Lakukan

Terobosan Selesaikan Masalah TKI [online]

https://www.voaindonesia.com/a/pemerintahan-

jokowi-lakukan-terobosan-selesaikan-masalah-

tki/2573013.html

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

218