Courting Violence: Opportunistic Parties and the Politics of Religion

Zahra Amalia Syarifah

University of Chicago, 5801 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637

Keywords : social movement, network analysis, content analysis, radicalism

Abstract : In 2016, the Islamic Defenders Front, Front Pembela Islam (FPI), a violent Islamic group, managed to

gather hundreds of thousands of people in a series of rallies in the Indonesian capital city. The rallies had

two important consequences: on one side, they influenced the election by swaying the voters’ preferences;

on the other side, they marked a turning point in the interactions between violent Islamic organizations and

political parties. Although FPI had campaigned and organized similar rallies to oppose the Christian

governor since 2014, only in 2016 that this issue was picked up by the public, which helped FPI to mobilize

them in large numbers. This suggests that there are conditions under which FPI is able to mobilize the

public, which were not there in 2014 but evidently were there in 2016. In this paper, I used network analysis

and computational content analysis on more than 25.000 news articles published between 2008 and 2018 to

examine why the same issue championed by FPI saw different levels of public and political party

engagement in 2014 and 2016. Furthermore, I employed network analysis to illustrate the changing

relationship between FPI as a violent group with political parties over the years.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2016, the Islamic Defenders Front, Front

Pembela Islam (FPI), a violent Islamic group,

managed to gather hundreds of thousands of people

in a series of rallies in Jakarta, the Indonesian capital

city. This peaceful protest was a shift from FPI’s

tendency towards raids and physical attack in the

previous decade. Rallies attendees accused Basuki

‘Ahok’ Tjahaja Purnama, Jakarta’s Christian

governor at that time, of blasphemy towards the

Islamic holy book, and pressured the government to

arrest him under the nation’s anti-blasphemy law. In

one of his speeches, Ahok had said that there were

people who misled the electorates by citing a

Quranic verse to stop them from voting for him in

the upcoming elections.

The public’s participation in the rallies and their

impact on the election changed Islamic

organizations and parties’ political strategies in a

more sweeping way. The rallies had two important

consequences: on one side, they influenced the

election by swaying the voters’ preferences; on the

other side, they marked a turning point in the

interactions of violent Islamic organizations and

political parties. In an attempt to secure popular

support, political party elites began to court violent

Islamic organizations by attending rallies held by

FPI (Kompas Cyber Media, 2017). Although the

governor did not mean to vilify the Islamic holy

book, FPI alleged that the governor’s words were an

insult to the Holy Quran, framing them as

blasphemous (BBC Indonesia, 2016). Several

political party figures attended these anti-Ahok

rallies in an effort to capture the Muslim electorates’

popular support in the upcoming Jakarta

gubernatorial elections. By the end of the elections,

a candidate who frequented FPI’s rallies came out

victorious, while the Christian governor was

imprisoned for blasphemy. The media has regarded

the governor’s imprisonment as a result of FPI’s

power in influencing the electorate to vote for

certain candidates, as well as in swinging the public

political discourse by framing their political

opponent as a potential threat towards Islamic values

(New York Times, 2017; Time, 2017).

Although FPI had campaigned and organized

similar rallies to oppose the Christian governor since

2014, only in 2016 that this issue was picked up by

the public, which helped FPI to mobilize them in

large numbers. This suggests that there are

conditions under which FPI is able to mobilize the

public, which were not there in 2014 but evidently

were there in 2016. When those conditions appeared

and FPI was able to mobilize the masses, this led to

political parties becoming interested with the group.

176

Syarifah, Z.

Courting Violence: Opportunistic Parties and the Politics of Religion.

DOI: 10.5220/0010274800002309

In Proceedings of Airlangga Conference on International Relations (ACIR 2018) - Politics, Economy, and Security in Changing Indo-Pacific Region, pages 176-185

ISBN: 978-989-758-493-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Political party elites’ attendance in FPI’s rallies in

2016 also marked the first time since the fall of the

authoritarian regime in 1998 that political parties

publicly engage violent Islamic groups. At the span

of two years between 2014 and 2016, with the same

anti-Christian governor issue, FPI managed to

mobilize hundreds of thousand people and attract

political party elites to attend their rallies.

I used network analysis and computational

content analysis on more than 25.000 news articles

published between 2008 and 2018 to examine why

the same issue championed by FPI saw different

levels of public and political party engagement in

2014 and 2016. Furthermore, I employed network

analysis to illustrate the changing relationship

between FPI as a violent group with political parties

over the years.

First, I present the methodology used in this

study. Afterwards, I explore how discourse around

FPI changes over time as they shift from violent

attacks to peaceful protests and show the evidence of

convergence between FPI and political parties.

Finally, I discuss how a violent Islamic group such

as FPI converged with political parties and I explore

what happened in 2016, and how political parties

began engaging violent Islamic groups. The final

section will conclude the paper by discussing

whether the convergence between FPI and political

parties means that violent Islamic groups are gaining

power in the national politics.

2 METHODS

I used network analysis to understand how different

political actors in Islamic organizations and parties

relate to each other over a ten years time period.

This highlights how FPI as a violent group rose to

power by mobilizing other Islamic groups and

engaging parties. I also employed computational

content analysis to process a large amount of data

and highlight discursive patterns arising throughout

time.

2.1 Dataset

I obtained the articles from English language

Indonesian news websites. I chose articles between

2008 and 2018 as in this period social movement

organizations flourish without the authoritarian

regime’s control. In addition to that, at this time

parties have had a decade of habituation to the new

democratic setting (Slater, 2015). This created a

dynamic political landscape that opened up

possibilities for interaction between the social

movement and parties.

While there is a lack of self-documentation by

the organizations regarding their activities, the

stories that are reported in national newspapers often

signal the events’ significance to historians

(Bingham, 2010). Thus, newspaper content analysis

is suitable to gauge how the media portrays different

Islamic groups and records their political activities

throughout time. This allowed me to examine the

shift in discourse regarding the Islamic social

movement in Indonesia.

I focused on four election cycles. By looking at

different time periods I inferred the network’s

temporal dimension and shows how the Indonesian

political constellation changes over time (Padgett

and Powell, 2012). The elections that I looked at in

this paper are: 1) the 2009 Legislative and

Presidential Elections (2008-2009); 2) the 2012

Jakarta gubernatorial elections (2011-2012); 3) the

2014 Legislative and Presidential Elections (2013-

2014); and 4) the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial

elections (2016-2017). Although the second and

fourth election cycles are at the provincial level,

Jakarta politics is often used to gauge a party’s

positioning in the national polity. By looking at the

elections as a cycle--each consisting of two years

beginning from the year prior to the election--I

captured the social game leading up to the vote. By

doing so, I observed the time where political parties

were scouting for viable coalition partners and

courting social movement organizations to gain

popularity among the electorates. Furthermore, by

focusing on different time periods, I compared FPI’s

different levels of mobilization over the same issue

in the third and fourth election cycles.

2.2 Methods: I. Network Analysis

The main idea of my methodology is to identify

actors in Islamic social movement and political

parties and count the actors co-occurrence in the

news articles. First, I drew an actor-to-actor graph to

show the relations between individual organization

and party actors. Then, I aggregated each actors to

their respective groups or parties to form

organizational nodes. In the organization-to-

organization graph, the weight of each

organizations’ ties are the aggregate of their actors’

co-occurrence values. To introduce time

dimensionality, I repeated this for all election cycles

between 2008 and 2018. However, this method

could fail to capture smaller groups and parties.

Political actors in smaller groups and parties

Courting Violence: Opportunistic Parties and the Politics of Religion

177

sometimes are not mentioned in news articles.

Instead of the actors, the articles usually refer to the

group or party’s name. To capture them, I used the

group or party’s name and treated them like

individual actors in other groups or parties.

To compare the networks, I measured network

centralization. Centralization describes the extent to

which the level of cohesion in a network is

organized around a particular node (Freeman, 1978;

Scott, 2000). I used betweenness centrality measure

to calculate network centralization based on the

shortest paths between two nodes in a graph where

the sum of the weights of its constituent edges are

minimized (Brandes, 2001; Freeman, 1978). When a

node has a higher centralization score, it signifies

higher leadership, influence, and control in the social

movement and party fields (Diani 2003; Diani and

McAdam, 2003; Osa, 2003).

2.3 Methods: II. Computational

Content Analysis

To explore the narrative between the actors, I

combined various computational methods to analyze

the text. Firstly, I used Word2Vec to project words

into vector spaces and determine certain words’

closeness to different political actors: FPI,

Muhammadiyah, and Nahdlatul Ulama as the three

largest Islamic organizations in terms of tie counts to

other groups and parties. Then I used POS tagger to

elicit precise claims in the text regarding these

organizations. Finally, I counted the violent words

frequency to show the shift in FPI’s preferred

political tactic. These computational content analysis

methods complement the network analysis by

providing context. Moreover, they were able to show

a shift in media discourse regarding FPI and other

Islamic groups

.

Word2Vec is a group of linguistics models used

to produce word embeddings. Its main idea is that

words are characterized and contextualized by other

words around it (Firth, 1957). Word2Vec takes a

large text corpus as its input and produces a vector

space with each word in the corpus being assigned a

corresponding vector in space. In the vector space,

the word vectors that share common contexts in the

corpus are located close to each other.

Using Word2Vec, I compared FPI with

Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama by

contrasting them on their preferred political tactics

dimension. I measured the words’ vector similarity

by using the cosine similarity--a measure that

calculates the cosine angle between words in

different vectors. By doing so, I identified which

words are the most and least similar to each other.

Finally, I used cosine similarity to project these

word vectors to arbitrary semantic dimensions. For

instance, I explored words that are related to FPI and

Nahdlatul Ulama--which are the semantic

dimensions that I wanted Word2Vec to project the

words unto--to see how the two organization’s

preferred political tactics differ.

I also used POS tagging to parse precise claims

in my news corpus using the Stanford POS tagger

and the Penn Treebank tag set to discover particular

word’s linguistic role in a sentence (Toutanova

et.al., 2003). This method extracted different parts of

speech most related to a keyword. For example,

when I chose ‘FPI’ as a keyword, I extracted

adjectives that describes or proper nouns that relates

most to FPI.

Finally, I counted violent and protest words to

show the trend for FPI’s preferred political tactic. I

compared the result with the way FPI is portrayed in

the media throughout the four election cycles to see

whether FPI’s change in tactic align with their

portrayal in the media. I examined whether parties

cooperate with them despite the persistence of their

violent label and how FPI framed their issue

differently in 2014 and 2016.

3 RESULTS

While the convergence between FPI and political

parties peaked in the 2016 - 2017 election cycle with

the Christian governor’s prosecution, the events

leading up to his removal from office started much

earlier. After the authoritarian regime’s fall in 1998,

Islamic social movement organizations and political

parties interact in a dynamic political landscape.

Within the first decade after the regime’s fall, a

number of Islamic groups that resorted to terrorism

and violent attacks emerged. Only after 2008 that the

government managed to tackle these terrorist groups.

Despite often engaging in violent attacks towards

minority groups and raiding entertainment venues

deemed unfit for Islamic values, the Susilo Bambang

Yudhoyono administration (2004 - 2014) deemed

that FPI is still less dangerous than other Islamic

terrorist and paramilitary groups (Hasan, 2006;

Kersten, 2015). Thinking that FPI is still under

control, the government was being lenient towards

them. However, FPI soon grew out of hand.

While the government has managed to keep

terrorism down, this leniency has sown seeds of

intolerance within the Muslim community. With the

background of this rising intolerance, FPI’s shift

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

178

towards less violent tactics and their successful issue

framing regarding their opposition to Ahok attracted

public support in 2016. This section presents my

findings to explain the events leading up to FPI and

political parties’ convergence in the 2016 - 2017

election cycle.

3.1 Network Analysis

Within the social movement network three

organizations appeared to consistently have the

highest number of ties (see Table 2). While

Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama had more ties

with political parties, FPI had more ties with more

Islamic organizations.

In the social movement network (grey nodes) we

can see that FPI, Muhammadiyah, and Nahdlatul

Ulama consistently had the highest number of ties

over the four election cycles. However, it is evident

that the three organizations have shown a divergent

pattern. Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama

consistently had higher or the same number of ties

with political parties than with social movement

organizations. Meanwhile, FPI always had a higher

number of ties with other social movement

organizations than with political parties. I explored

the difference between FPI, Muhammadiyah and

Nahdlatul Ulama with computational content

analysis in the next section.

Amongst all other Islamic organizations in this

study, FPI consistently had the highest betweenness

centrality score. This means that FPI had a higher

level of leadership, influence, and control in the

multi-organizational social movement and political

party field (Diani, 2003). The evidence also shows

that FPI had more ties with other social movement

organizations than any other Islamic groups, which

inferred FPI’s ability to mobilize resources from

other organizations within the movement. Thus,

despite their violent tendencies, FPI had was more

capable to mobilize resources than any other Islamic

groups that are not violent.

3.2 Computational Content Analysis

Using Word2Vec, I projected action words that

represent various political tactics, ranging from

contentious ‘street’ politics such as protests that are

preferred by social movements to forming coalitions

preferred by political parties (Heaney and Rojas,

2015). The result suggests that FPI is more

confrontational than Nahdlatul Ulama and

Muhammadiyah. For instance, words such as attack,

raid, protest, vigilante, and rally are associated

closely with FPI. Meanwhile, more collaborative

words such as speech, coalition, and support are

related closer to Nahdlatul Ulama and

Muhammadiyah. When I projected the political

tactics dimension into ‘social movement’ and

‘political party’, the result suggests that social

movements generally adopt more confrontational

tactics such as protest and raid while political parties

prefer more collaborative tactics such as forming

coalitions or campaigning for the party or the

candidate. The result suggests that Muhammadiyah

and Nahdlatul Ulama adopts a similarly

collaborative tactics as parties while FPI generally

takes more confrontational tactics than

Muhammadiyah, Nahdlatul Ulama, or parties.

Despite being consistently described by the

media as more violent and aggressive than other

Islamic organizations, political parties still form ties

with FPI. Unlike, the adjectives that remained

consistent throughout the four election cycles, the

verbs that are closely related to FPI changes over

time. In the 2008 - 2009 election cycle, FPI had

more aggressive verbs such as attack, prosecute, and

disband. This pattern recurred in the 2011 - 2012

and 2013 - 2014 election cycles with verbs such as

threat and force. However, in the last election cycle

verbs related to FPI were less aggressive than the

previous time periods. This result suggests that

while FPI may change their preferred political tactic,

their violent image stayed with them throughout the

four election cycles.

The POS tagging that I used revealed the

Islamists political power in the elections. In the 2008

- 2009 election cycle, the voters were described as

Muslim electorates that are eligible to vote. In the

next cycle, the word registered describes the voters.

These two election cycles does not seem to show

any strong characteristics of the voters despite that

they are eligible Muslim voters. However, in the

2013 - 2014 election cycle, the adjectives that are

used to describe the voters began to shift. Aside of

being described as Muslim voters that are eligible to

vote, they are also described as young, undecided in

political matters, and thus they are potential allies

for political parties. Finally, in the last election cycle

the voters were described as intimidating, which

suggests the extent to their political power. This

result suggests that the Islamists are a viable

political ally for political parties due to their

electoral power.

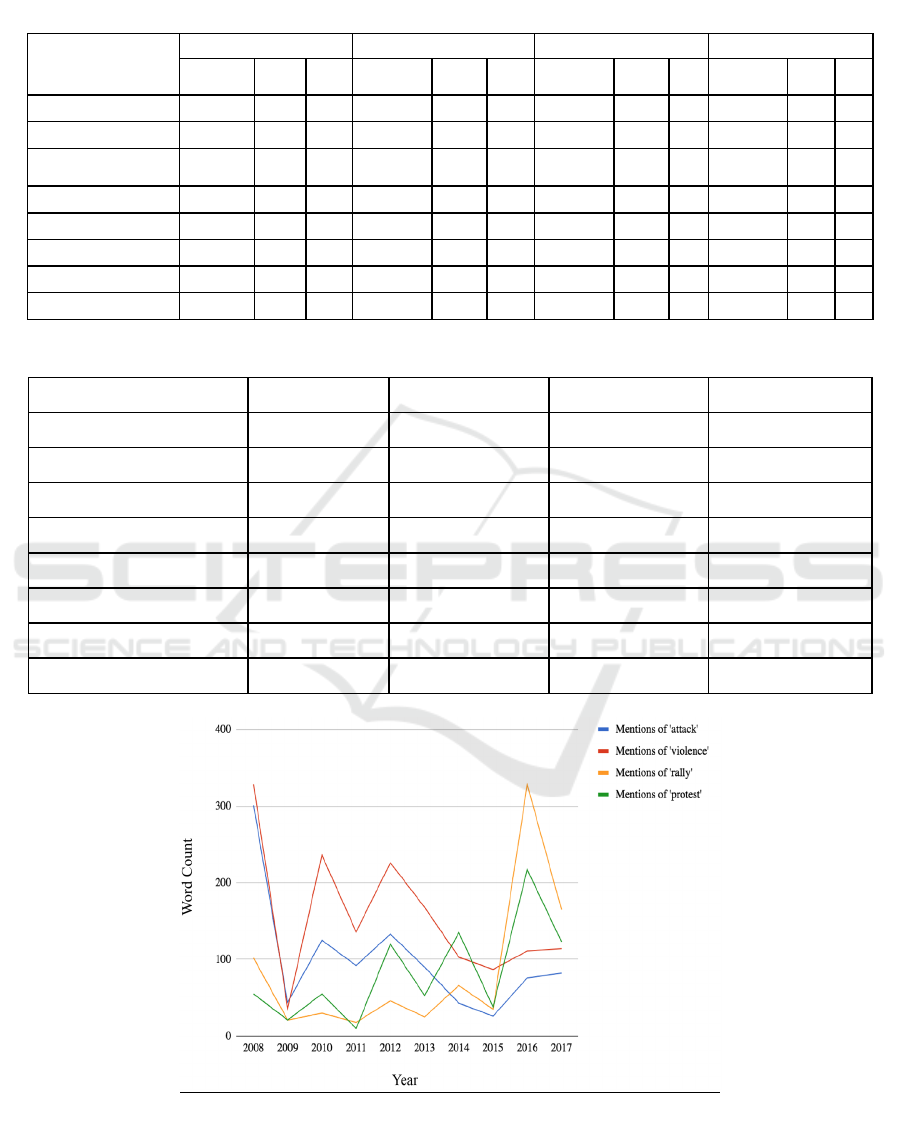

Finally, to examine a shift in FPI’s discourse

further, I counted words such as protest, violence,

and vigilante in articles regarding FPI. The trend

shows that between 2008 and 2013 the mention of

Courting Violence: Opportunistic Parties and the Politics of Religion

179

both attack and violence were higher than rally and

protest (Figure 1). This trend was reversed after

2013. This result suggests that FPI has preferred to

engage in rallies and protests than in attacks and

violence as in 2008 - 2013. This shift in preferred

political tactic opened up a point of convergence

between political parties and FPI. As FPI tempered

their political tactics, parties are more likely to be

engaged with them than when they were violent.

Despite their violent tendencies and their

enduring violent image, FPI has adopted a less

violent political tactic, which opened a point of

convergence between the movement and political

parties. Yet, it is not only because FPI has shifted

their political tactic that political parties were keen

to form ties with them. The network analysis in this

study has revealed that FPI had more ties with other

organizations, which demonstrated their capacity to

mobilize people and resources. This suggests that

political parties in opposition engage Islamic groups

to gain popular support amongst the Islamists. The

discussion section will explore how FPI’s shift in

tactic, their discourse framing, and the parties’

search for electoral support made the convergence

between a violent Islamic social movement

organization with political parties possible.

4 DISCUSSION

The evidence I presented in the Findings section

suggests that FPI’s success in garnering support and

engaging parties was due to their shifting tactics,

from violent actions towards more peaceful protests.

However, FPI’s shifting tactics were not sufficient to

mobilize the public and other Islamic groups, and

engage parties. In 2016, FPI framed its anti-Ahok

issue in a way that resonates with the majority of the

electorates, which are the more moderate Muslims.

FPI broadened their issue by using discursive

conflation methods (Mische, 2003), framing it as a

defense from threats to Islamic values rather than

pushing its narrower agenda of opposing to the

Christian governor. By adopting less violent political

tactic and carefully framing their issue, FPI engaged

the wider public, other Islamic groups, and parties

who might be averse to participating in violent

actions.

The year 2008 marked a decade of FPI’s

existence. Since the fall of the authoritarian regime

in 1998, FPI has taken a role of moral police to

enforce Islamic values. Between 2008 and 2009, FPI

members were often found raiding bars and nightlife

venues, citing these venues ‘unfit for an Islamic

majority country’. Despite having to deal with the

police and threats of disbandment by the

government, FPI retained their preference for

vigilantism to institute what they consider as Islamic

practices into the society. FPI’s hard-line stance on

Islam’s role in the public life causes other Islamic

organizations to denounce FPI and distance

themselves from FPI (Kersten, 2015). Their

engagement in vandalism, violence, and attacks

towards non-Muslims and the Ahmadiyya minority

group furthered their radical brand.

Figure 1 shows the number of word counts for

‘attack’, ‘violence’, ‘rally’, and ‘protest’ in articles

mentioning FPI over the four election cycles. The

word frequency suggests that while FPI is still

associated with the word ‘attack’ and ‘violence’ in

the 2016 - 2017 election period, but the word ‘rally’

and ‘protest’ exceeds their count. This suggests the

shift in FPI’s tactic from violence to relatively

peaceful protests. These protests are often joined by

other Islamic groups, thus forming organizational

ties between FPI and other groups in the social

movement network. This is evident in the rising

number of organizational ties in 2016 - 2017 (Table

1). By adopting less violent political tactic, FPI

engaged the wider public who might be averse to

participating in violent actions. However, their shift

in tactic alone was not enough to garner the masses.

FPI’s preference towards protest was also coupled

with a shift in the way they frame their issue.

In 2014, FPI began to organize protests against

the appointment of a Christian governor of the

capital city. Citing a verse in the Quran that forbids

Muslims to have non-Muslim leaders, FPI refused to

acknowledge him as a governor. FPI branded him as

an infidel and appointed their own Muslim governor

(Tempo, 2014). However, FPI’s attempt to frame

Ahok as an infidel did not resonate with the public

and other Islamic groups that took a more moderate

stance than FPI. Nahdlatul Ulama, a pro pluralism

Islamic organization, openly denounced FPI’s

actions as they perceive FPI’s politics as divisive

(Kersten, 2017). Nahdlatul Ulama believes that

Islam is a message of peace and unity, and thus

prefer to promote religious tolerance. This ideology

is not shared by FPI who took a more radical

approach to strive for the institution of Islamic

values in public life.

Only in 2016 did FPI’s issue resonate with the

public and other Islamic groups. In 2016, shortly

before the Jakarta gubernatorial election is set to

take place, a video of the Christian governor’s

allegedly blasphemous speech went viral in

Facebook. In his speech, the governor mentioned

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

180

that the voters are being misled by people who used

a Quranic verse to justify opposing him as a

governor. The video was edited in a way that

changed the meaning of the governor’s words,

making it seem like he said that the Quranic verse is

deceiving voters. A public outcry spreaded in

Facebook and Twitter as the governor’s words were

deemed as an insult to the Islamic holy book. This

opportunity is quickly picked up by Islamic social

movement organizations to bolster their agenda.

Leveraging on the public sentiment and shifting

up the discourse to include a wider range of

audiences, FPI formed an alliance with other Islamic

groups, framing their political agenda as a religious

‘fight to defend the Quran’. These discourse

conflation mechanisms (Mische, 2003) engaged the

more moderate share of Muslim, while also retaining

FPI’s radical stance. By doing so, FPI framed its

issue as a defense of Islamic values rather than just a

protest against the Christian governor. This also

allowed FPI to frame the government as a threat to

all Muslims.

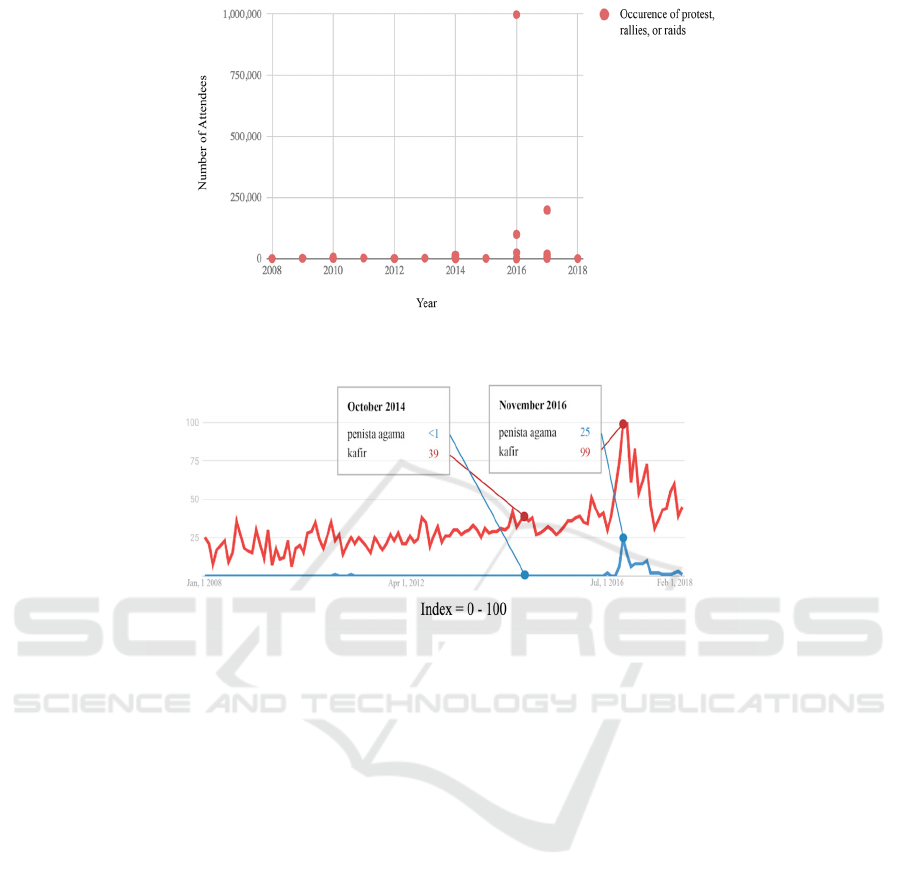

The issue resonated with the public and other

Islamic groups, and thousands of people attended a

series of rally to demand the governor’s

incarceration. In the first rally of the series in

October 2016, 25.000 people gathered in the capital

city’s mosque before marching towards the city hall.

By December 2012, the number of people who

attended FPI’s rally peaked at an estimated number

of 1.000.000 people (CNN Indonesia, 2016). This

number is remarkable, considering FPI’s violent

image and their protest attendance record that

seldom exceeded hundreds of people (Figure 2). The

large number of attendants and the participation of

other social movement organizations in the rally

signalled FPI’s potential in mobilizing people and

resources. Yet, this success is not solely attributed to

FPI’s mobilization capabilities.

Although the campaign to oppose the Christian

governor had begun since his appointment in the

fourth quarter of 2014, only in the October 2016 was

the protest event attended by tens of thousand. FPI’s

agenda hardly changed, but FPI changed the way

they framed the issue. Figure 3 shows internet search

engine trendlines for specific keywords between

2008 and 2018 that were accessed from Indonesia.

Internet search engine trend reflects public interest

in a certain topic. Thus, it shows how engaged the

public is with FPI’s issue. In 2014, FPI branded

Ahok as an infidel who is not fit to lead the capital

of a Muslim majority country. As seen in Figure 3,

the trendline for the term kafir (infidel in

Indonesian) rose only marginally in 2014 when FPI

launched the initial campaign. This suggests the

issue’s lack of resonance within the wider public or

other Islamic groups. Meanwhile, following Ahok’s

speech in 2016, the search for both penista agama

(blasphemer in Indonesian) and kafir saw an

exponential increase. The trend lines suggest that

FPI’s political framing caught up with the wider

public much more successfully in 2014. Calling the

governor an infidel to justify refusal to acknowledge

him had a divisive and exclusive tone to it, which is

perhaps why FPI’s issue did not resonate with the

public as much as in 2016. However, by using the

term blasphemer, FPI broadened the discourse they

used to present their issue by framing the governor’s

speech as an attack to Islam. This in turn justifies

opposition to the governor and calls to convict him

for blasphemy. This success is evident in Figure 3

where the trend line for the term penista agama

remained flat before it peaked in 2016 when FPI

blown up the blasphemy allegations through a series

of anti-Ahok rallies.

Unlike Heaney and Rojas (2015) who suggested

that social movements have to moderate their issue

stance to engage political parties, the evidence from

this study suggests that they might not need to

moderate their issue position. In this case, FPI did

not moderate their issue position, but they shifted

their framing regarding the anti-Christian governor

issue. As FPI’s campaign attracted tens of thousand

in its first rally of the series in October 2016,

political parties began to look at FPI as a viable

political ally for the 2017 elections. At the second

rally of the series in November 2016 who was

attended by 100.000 protesters, elites from at least

three parties in the government opposition attended

the event and publicly supported the cause by

endorsing it in news interviews At this point, it is

apparent that the candidates that attended FPI’s

rallies set themselves as the incumbent governor’s

opposition and attempted to leverage on the Islamic

movement’s support in the elections. Following the

victory of Gerindra’s candidate, both Demokrat and

Gerindra elites stopped attending the rallies.

Yet, FPI’s convergence with parties does not

suggest Islamic violent group’s acceptance and rise

to the national politics. After the elections in 2017

and Ahok’s imprisonment, FPI attempted to broaden

its issue. Instead of just defending the Quran, they

framed defending the ulama (Islamic scholars or

community leaders) as a part of defending Islam

against its aggressors.

Like the anti-Christian governor rally series, FPI

organized a number of protests in defense of the

ulamas. Yet, instead of seeing a high number or

Courting Violence: Opportunistic Parties and the Politics of Religion

181

attendants as in 2016, the number of protester

continually declined and party elites rarely attended

the rallies between the second half of 2017 and

2018. This suggests that the public and other Islamic

organizations’ attendance in FPI’s rallies does not

mean that they are supporting FPI but rather only

some of their causes. Furthermore, as party elites

stopped attending and endorsing FPI’s rallies, the

convergence between FPI and political parties seems

to be waning. FPI’s convergence as a violent Islamic

group with political parties and its resonance with

the wider public only happened under favourable

conditions, which were at the time when they framed

their issues in a way that appeals to the public, when

FPI is engaged in peaceful tactics that allows

political parties and more moderate Islamic groups

to join them, and during a period where Islamic

social movement’s support is needed by political

parties.

5 CONCLUSION

An intersection between party and social movement

may occur, when they serve one another’s needs.

Yet, due to tensions caused by differences in social

movement and party’s approach to politics,

collaboration between them might not happen.

Usually, social movement carries political agenda

that lies at an extreme end of the political spectrum,

but parties tend to broaden and moderate their issue

position to engage the majority of the voters. Thus,

social movement organizations often had to

moderate their issue to engage political parties

(Heaney and Rojas, 2015). Yet, in this case, due to

careful issue framing and skilled use of discursive

conflation mechanisms FPI did not need to moderate

their issue upon their convergence with political

parties.

FPI used discourse conflating mechanisms to

move between higher or lower levels of abstraction

regarding the generality or inclusiveness of identity

categories within a movement, from framing the

issue as an anti-Christian leader towards a defense

against Islam’s aggressors that resonated with the

more moderate public rather than just the radical

niche. Thus, FPI could target different segments of

the population: the more radical Islamists to the

more moderate Islamic groups, political parties, and

the public. The way FPI slide between the general--a

religious defense--and the particular--anti-Christian

leader--works to build relations in a public arena,

while also maintaining FPI’s latent particularistic

identity as an Islamic radical group. By carefully

framing their discourse, FPI is able to engage and

mobilize a wide range of actors and organizations in

the social movement network, which then attracted

political parties to converge with them despite their

violent tendencies.

Despite FPI’s violent tendencies, they had more

ties with Islamic groups than with parties. This

exhibited FPI’s ability to frame a discourse that

resonates with a wide range of audiences and FPI’s

ability to mobilize their audiences. Furthermore,

FPI’s success in framing their issue to engage

Muslim voters attracted parties who wished to

appeal to this demography in the upcoming election.

However, FPI’s success in instituting their

demand to impeach the Christian governor should

not be taken as a sign that social movements have a

direct effect towards the country’s governing body--

which is the judicial body in this case. FPI’s success

operates through their ability to mobilize a large

number of people, which demonstrates an attention-

grabbing show of political opinion through an

exponential increase in protest activity and

attendees. FPI’s capability to mobilize protesters

consisting of the public and other Islamic groups,

informed the ruling government--and also political

parties--of the electorate’s desires, which then

responded to FPI’s demands. This is consistent with

Burnstein and Linton’s (2002) study that argues that

organizational activities that respond to the

politicians’ electoral concerns--which is informing

them about the electorates’ opinion and potentials in

the upcoming elections--are more likely to have an

impact. This suggests that social movement’s impact

is contingent upon their ability to serve the ruling

elite or party elite’s interests: violent Islamic groups

will attract political elites only to the extent that their

activities provide these elites with information and

resources relevant to their electoral prospects.

REFERENCES

Ansell, C.K., 2001. Schism and Solidarity in Social

Movements: The Politics of Labor in the French Third

Republic. Cambridge University Press.

BBC Indonesia, 2016. Pidato di Kepulauan Seribu dan

hari-hari hingga Ahok menjadi tersangka. BBC News

Indonesia.

Bingham, A., 2010. ‘The Digitization of Newspaper

Archives: Opportunities and Challenges for

Historians.’ 20 Century Br Hist 21, 225–231.

Brandes, U., 2001. A faster algorithm for betweenness

centrality. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology 25,

163–177.

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

182

Broadbent, J., 1999. Environmental Politics in Japan:

Networks of Power and Protest. Cambridge University

Press.

CNN Indonesia, 2016. Menghitung Jumlah Peserta

#Aksi212 di Jantung Jakarta. CNN Indonesia.

Diani, M., 2003. “Leaders” or Brokers? Positions and

Influence in Social Movement Networks, in: Social

Movements and Networks: Relational Approaches to

Collective Action. Oxford University Press, Oxford,

pp. 105–122.

Diani, M., McAdam, D., 2003. Social Movements and

Networks: Relational Approaches to Collective

Action. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Firth, J.R., 1957. Studies in Linguistic Analysis.

Blackwell.

Freeman, L.C., 1978. Centrality in Social Networks:

Conceptual Clarification. Social Networks 1, 215–239.

Hasan, N., 2006. Laskar Jihad: Islam, Militancy, and the

Quest for Identity in Post-New Order Indonesia. SEAP

Publications.

Heaney, M.T., Rojas, F., 2015. Party in the Street.

Cambridge University Press.

Kersten, C., 2017. History of Islam in Indonesia: Unity in

Diversity. Edinburgh University Press.

Kersten, C., 2015. Islam in Indonesia: The Contest for

Society, Ideas and Values. Oxford University Press.

Kompas Cyber Media, 2017. Fadli Zon: Ada Perintah dari

Istana Cari Persoalan Pajak Saya. KOMPAS.com.

Melucci, A., 2017. An end to social movements?

Introductory paper to the sessions on “new movements

and change in organizational forms”: Social Science

Information.

Melucci, A., 1996. Challenging Codes: Collective Action

in the Information Age. Cambridge University Press.

Mische, A., 2008. Partisan Publics: Communication and

Contention Across Brazilian Youth Activist Networks.

Princeton University Press.

Mische, A., 2003. Cross-talk in Movements: Reconceiving

the Culture-Network Link, in: Social Movements and

Networks: Relational Approaches to Collective

Action. OUP Oxford, Oxford, pp. 258–280.

Mische, A., Pattison, P., 2000. Composing a civic arena:

Publics, projects, and social settings. Poetics,

Relational analysis and institutional meanings: Formal

models for the study of culture 27, 163–194.

New York Times, 2017. Indonesia Governor’s Loss

Shows Increasing Power of Islamists. The New York

Times.

Osa, M., 2003. Networks in Opposition: Linking

Organizations Through Activists in the Polish

People’s Republic, in: Social Movements and

Networks : Relational Approaches to Collective

Action: Relational Approaches to Collective Action.

OUP Oxford, Oxford.

Padgett, J.F., Powell, W.W., 2012. The Emergence of

Organizations and Markets. Princeton University

Press.

Pfeffer, J., 1994. Managing with Power: Politics and

Influence in Organizations. Harvard Business Press.

Scott, J., 2000. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook.

SAGE.

Slater, D., 2015. Democratic Disarticulation and its

Dangers: Cleavage formation and promiscuous power

sharing in Indonesian party politics, in: Building

Blocs: How Parties Organize Society. Stanford

University Press, pp. 123–150.

Sudhahar, S., Fazio, G. de, Franzosi, R., Cristianini, N.,

2015. Network Analysis of Narrative Content in Large

Corpora. Natural Language Engineering 21, 81–112.

Tarrow, S.G., 2011. Power in Movement: Social

Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge

University Press.

Tempo, 2014. FPI Pilih Gubernur Jakarta Fahrurrozi.

Siapa Dia? Tempo.

Tilly, C., 1994. Social Movements as Historically Specific

Clusters of Political Performances. Berkeley Journal

of Sociology 38, 1–30.

Time, 2017. Indonesia: Christian Official Jailed for

“Blaspheming Islam” [WWW Document]. Time. URL

http://time.com/4770985/jakarta-governor-ahok-

christian-jail-blasphemy-islam

Toutanova, K., Klein, D., Manning, C.D., Singer, Y.,

2003. Feature-rich Part-of-speech Tagging with a

Cyclic Dependency Network, in: Proceedings of the

2003 Conference of the North American Chapter of

the Association for Computational Linguistics on

Human Language Technology - Volume 1, NAACL

’03. Association for Computational Linguistics,

Stroudsburg, PA, USA, pp. 173–180.

Courting Violence: Opportunistic Parties and the Politics of Religion

183

APPENDIX

Table 1: Number of Islamic Social Movement Organization Ties.

2008 - 2009 2011 - 2012 2013-2014 2016-2017

Organizatio

n

Parties Total

Organizatio

n

Parties Total

Organizatio

n

Parties Total

Organizatio

n

Parties Total

Forum Umat Islam 1 0 1 3 2 5 2 3 5 3 1 4

FPI 7 3 10 8 2 10 8 8 16 12 8 20

Himpunan Mahasiswa

Isla

m

1 1 2 4 5 9 3 2 5 2 2 4

Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia 4 2 6 5 1 6 4 2 6 3 3 6

ICMI 1 4 5 1 0 1 4 1 5 1 2 3

Muhammadiyah 6 8 14 6 3 9 7 9 16 7 7 14

MUI 4 4 8 6 4 10 4 5 9 4 4 8

Nahdlatul Ulama 6 8 14 6 6 12 6 10 16 4 8 12

Table 2: Number of Islamic Social Movement Organization Ties.

Betweenness Centrality 2008 - 2009 2011 - 2012 2013 - 2014 2016 - 2017

Forum Umat Islam 0 0.632983683 0.4678571429 2.390079365

FPI 89.10682274 64.51155511 53.21230159 172.4405844

Himpunan Mahasiswa Islam 0 35.06496026 1.2 4.95952381

Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia 0.3404344194 0.5928571429 0.5333333333 0.1111111111

ICMI 0.1611111111 0 0.75 0.1111111111

Muhammadiyah 26.26791248 13.49797787 12.55515873 21.23943001

MUI 2.150793651 13.95712684 1.40952381 3.500865801

Nahdlatul Ulama 35.12112886 22.83587642 16.46349206 5.536904762

Figure 1: Trend Line for Word Mentions in FPI News Articles.

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

184

Figure 2 : Number of Attendees in FPI Protests, Rallies, or Raids.

Figure 3 : Internet Search Engine Result Trend Line for ‘Infidel’ and ‘Blasphemous’

Courting Violence: Opportunistic Parties and the Politics of Religion

185