Should We Worry about China? China’s Outward FDI and Aid in

Indonesia

Citra Hennida

Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya

Keywords: foreign direct investment, dependency, foreign policy, foreign aid.

Abstract: Based on data from the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM), Chinese investment in Indonesia has

increased significantly in recent years. The number of Chinese investments increased 12 percent in 2017 and

shifted Japan's position as the second largest investor in Indonesia after Singapore. Indonesia's foreign debt

to China also increased. Between 2010 and 2016, Indonesia's debt to China increased six times. It is the largest

compared to the average increase of Indonesian debt to other countries that is only 1.3 points. This situation

raises concerns that Indonesia's foreign policy will benefit China a lot. This concern is justified because there

is no binding agreement beyond economic cooperation. Departing from this issue, research discusses whether

the level of investment and large debt to China will affect the independence of Indonesia's foreign policy. The

study was conducted in the period of 2014 to 2018 during Joko Widodo presidency.

1 INTRODUCTION

Chinese investment in Indonesia is increasing. The

Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) noted that

China is the second largest investor in Indonesia after

Singapore. The amount of Chinese investment in

Indonesia in 2017 was US$ 5.5 billion, up 12% from

the previous year which amounted to US$ 4.9 billion

(The Jakarta Post, January 24, 2018). For the size of

ASEAN, China's investment in Indonesia is the most.

Based on data from BMI Research in 2017, there are

46 projects supported by Chinain Indonesia;

meanwhile 31 projects are in Laos, 30 projects are in

Vietnam and Malaysia, 20 projects are in Cambodia,

12 projects are in Singapore, 7 projects are in

Philipines, 6 projects are in Myanmar, and 5 projects

are in Thailand (Salikha 2018).

The flood of Chinese investment in the region is

almost inevitable. Data at the end of 2013 shows that

China is at number three in the world's largest

investor country for FDI of US$ 101 billion (Wang,

Qi, Zhang 2015). According to China's Ministry of

Commerce in 2014, Chinese companies invested US$

116 billion in 156 countries. China's ODI growth is

between 19-22% since 2013 (Wang 2014). It is also

projected that China's investment is growing as

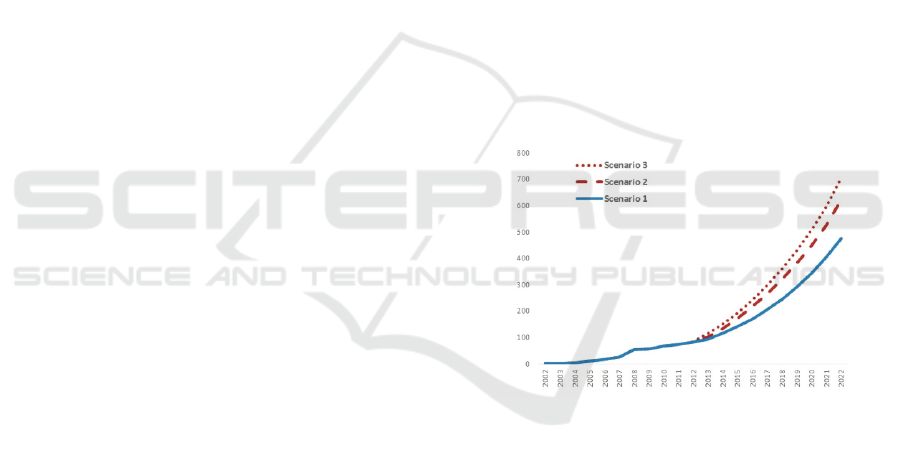

shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Growth Estimation of Chinese ODI 2013-2022

(US$ billion)

China currently has a lot of money and big

markets. China is geographically close to ASEAN

countries. ASEAN is seen as providing many low-

cost manufacturing industries, a market that continues

to grow and is in line with Xi Jinping government's

goal of reviving the silk trade route which is the

channel of intercontinental infrastructure linking

Europe, Central Asia, South Asia and Southeast Asia.

For ASEAN countries, China's investment is needed

to strengthen fiscal savings and infrastructure

spending. The United States and Western European

economies that have not fully developed due to the

global crisis in 2008 left China as a major player in

global financing through AIIB (Asian Infrastructure

Investment Bank) and FDI (Foreign Direct

38

Hennida, C.

Should We Worry about China? China’s Outward FDI and Aid in Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0010272800002309

In Proceedings of Airlangga Conference on International Relations (ACIR 2018) - Politics, Economy, and Security in Changing Indo-Pacific Region, pages 38-46

ISBN: 978-989-758-493-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Investment) flows. Moreover, China through Belt

Road Initiatives introduced in 2013 by President Xi

Jinping provides a lot of potential infrastructure

cooperation which includes overland "Silk Road

Economic Belt" and sea-based "Maritime Silk Road".

BRI's proposals in the future also include non-

infrastructure investment, namely cultural ties and

people-to-people exchanges (Hillman 2018).

President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) captured this

opportunity. President Jokowi stressed the

importance of infrastructure development to

accelerate economic growth. China's investment in

Indonesia is mostly in mining, infrastructure and

tourism. On the occasion of meeting with Chinese

President Xi Jinping May 14, 2017, Jokowi invited

the Chinese Government to cooperate on three mega

projects. The three-mega projects are located in North

Sumatra, namely the construction of the Kuala

Tanjung Port facility and the Medan-Sibolga toll

road; in North Sulawesi, namely the construction of

road infrastructure, railways, ports and airports in

Bitung-Manado-Gorontalo; in North Kalimantan,

namely energy investment and construction of a 7200

megawatt power plant. On the same occasion, the

Government of Indonesia and the Government of

China also signed several documents, namely 2017-

2021 Indonesia-China Comprehensive Strategic

Partnership, China Economic and Technical

Cooperation, and Jakarta-Bandung rapid train project

(setkab.go.id).

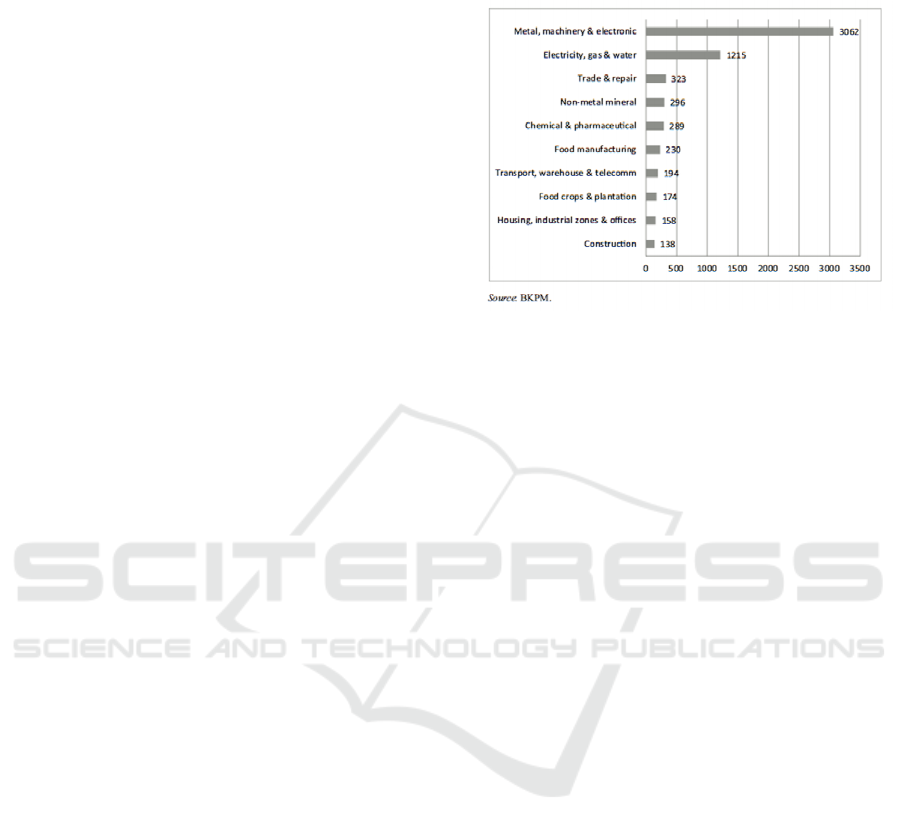

Based on BKPM records during 2004-2015 there

are about 2500 direct investment projects from China

and 1100 projects from Hongkong. This amount is

even greater considering that Chinese companies are

also channeling their investments through Singapore.

In addition Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will also

spread to sectors outside of mining such as property

and e-commerce. The involvement of Chinese

companies in Indonesia are through two mechanisms:

FDI mechanisms and mechanisms of the BRI. A large

number of companies are involved because they take

part in the Belt and Road Initiative.

The magnitude of FDI can boost the economy

(Korbin 2005; Morisset & Pirnia 2001). FDI offers

several advantages: (1) technology transfer and

capability; (2) opening employment opportunities for

communities in receiving countries; (3) encouraging

the privatization and commercialization of SOEs; (4)

FDI is deemed able to maintain the exchange rate

because the incoming FDI equals the entry money for

the country; (5) generating sustainable economic

activity; (6) creating cooperation with local

businesses, for example through joint-ventures; (7)

infrastructure development in recipient countries; (8)

receiving countries benefit from CSR (Corporate

Social Responsibility) run by foreign corporations

residing in the country (Onyeiwu tt).

On the one hand Nunnenkamp & Spatz (2004)

argues that there is no empirical evidence that foreign

investment has a direct impact on growth. Herzer et

al (2006) adds that foreign investment in the short run

does indeed contribute to economic growth but in the

long run there is no correlation. Milanovic (2002)

states similar argument by saying that there is no

relationship between foreign investments with the

increase of people's income. There are other

indicators that need to be developed. These indicators

are trading volume (De Mello, 1999); domestic

market, competition level and human capital

(Balasubramanyan et al, 1996); government

regulations, the development of other economic

sectors and industry readiness in the country (Agosin

& Mayer, 2000).

The magnitude of Chinese foreign investment and

aid has led to consequences such as the increasing

number of Indonesia's foreign debt to China which

rose by 6 times between 2010 and 2016. It is the

greatest increase in comparison with the average

increase in debt to other countries outside China is

only 1.3 times. Second, Chinese contractors and sub

contractors seek and obtain raw materials and

equipment from suppliers in China and do not use

local suppliers. Third, about half of the Chinese

experts working in Indonesia are employed in the

construction sector (Kong & van de Eng 2018).

Additionally, the dominance of investment and debt

are feared will affect the independence of Indonesian

foreign policy.

Departing from the above background, this study

aims to find a correlation whether the dominance of

investment from China affect the independence of

foreign policy of Indonesia against China. This study

was limited to Jokowi presidency. During his

presidency in 2014, Chinese investment in Indonesia

and Indonesia’s debt to Chian increased rapidly. The

study found that Indonesian foreign policy tends to be

pragmatic and utilizes its position as a middle power

that leads to great power of the region. With this

position Jokowi is more hedging in the face of China.

Indonesia's hedging attitude is influenced by the

domestic political situation. Jokowi’s political

opponents mostly play the issues of China and

Chinese Indonesians by utilizing the still high

stereotypes over China and Chinese Indonesians in

public and domestic elites.

Should We Worry about China? China’s Outward FDI and Aid in Indonesia

39

2 METHOD

This study focuses on the relationship between

foreign investment and foreign policy. This type of

research uses descriptive research type as an attempt

to explain and interpret a particular phenomenon,

problem or behavior. In this study the authors aim to

explain how the dominance of foreign investment

affect the independence of foreign policy of the

recipient country to the donor country. FDI in

question is FDI from China. The foreign policy in

question is the foreign policy of Indonesia during

Jokowi's reign of China, both bilaterally and

multilaterally. Data are presented in the form of

primary data and secondary data. Primary data were

obtained from institutional reports, institutional

survey results, and public officials' statements.

Secondary data obtained from books, journals, and

news in the media. Data analysis technique used in

this research is qualitative analysis. Qualitative

analysis in a study emphasizes the interpretation of

data and statements obtained from secondary data

collection and primary which is then associated with

theories, concepts, and preposition that have been

determined by researchers. This qualitative analysis

consists of three activities simultaneously: data

reduction, data presentation and conclusion or

verification.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The number of Chinese FDI in Indonesia and the

amount of Indonesia's debt to China is large. Table 1

shows the realization of Chinese FDI in Indonesia

2010-2017 in million dollars. In addition, Indonesia's

loan to China through Asia Infrastructure Investment

Bank (AIIB) also increased. From US$ 800 million in

2007 increased to US$ 15.7 billion in 2017 with loan

composition for private sector of 92% and

government 8%. The portion of debt to China has

increased from 0.6% in 2008 to 4.5% in 2017. While

debt to Japan which has been the traditional partner

of Indonesia declined; from 23.8% in 2008 to 8.3% in

2017 (Negara & Suryadinata 2018). Based on data

from Bank Indonesia April 2018, Indonesia's debt to

China doubled to US$ 16.7 billion. Data is taken

without including Hong Kong. If Hong Kong is

involved then the data will get bigger (Haswidi 2018).

Table 1: Chinese FDI Realisation in Indonesia 2010-2017

(US$ million)

Before Jokowi’s administration, China was

involved in projects such as the Surabaya-Madura

Bridge, an electric generator project, the construction

of the Jatigede dam. In the Jokowi period, China was

involved in the construction of hydro-power, the

Jakarta-Bandung highway project. At the meeting in

BRI Summit in May 2017, Jokowi offers port

development in Kuala Tanjung, Bitung and Bali

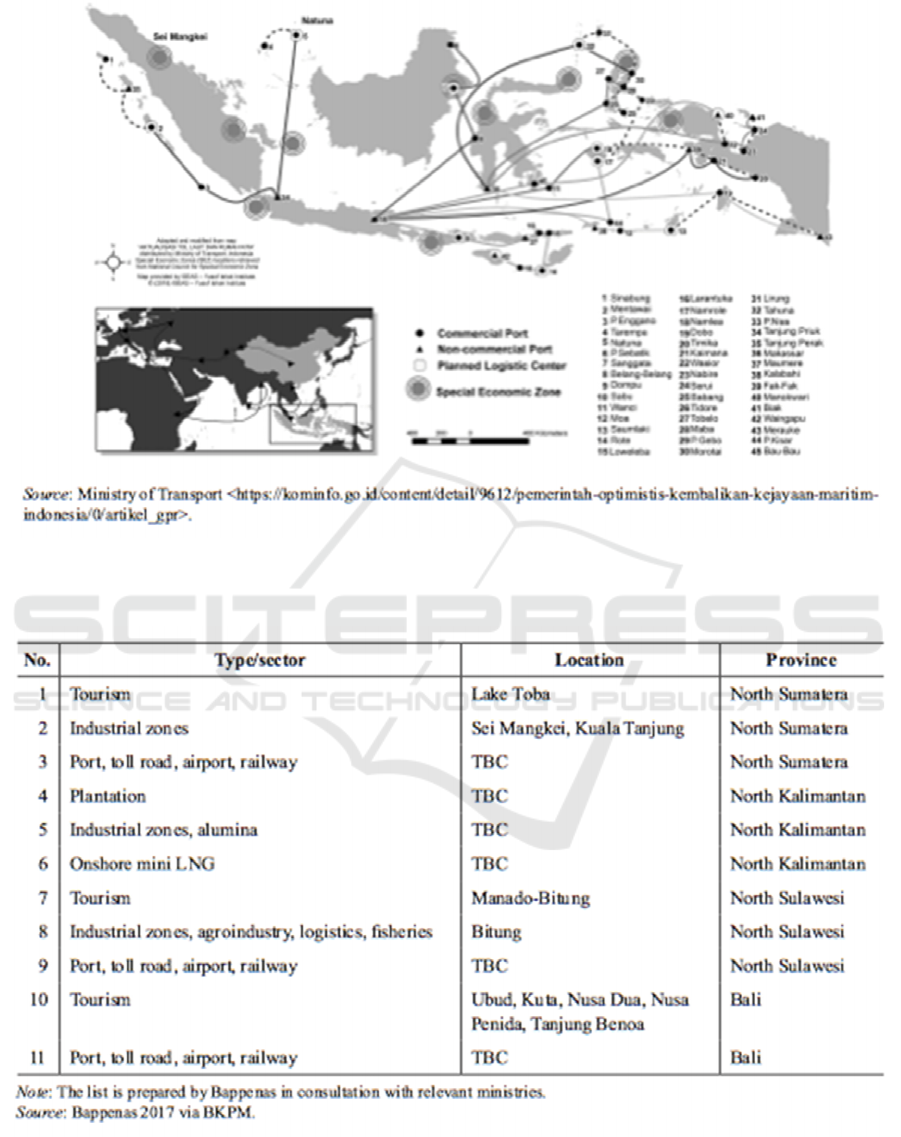

(Kompas, May 16, 2017). Table 2 shows the project

proposed by Indonesia to be financed by BRI.

Indonesia also does not close the possibility of

financing by other parties outside BRI. As shown in

Figure 2, Indonesia's maritime development plan is

also not related to BRI's development plan. Specific

projects approved by both countries also do not exist

yet (Negara & Suryadinata 2018). Indonesia also

secured a US$ 2.4 billion loan from AIIB. This loan

is to finance programs to improve urban transport

infrastructure, improve slum areas, cheaper housing,

and dam construction and irrigation. The financing

distribution is National Slum Upgrading Project (US$

217 million), Regional Infrastructure Development

Fund (US $ 100 million), and Dam Operation

Improvement Project (US $ 125 million) (Das 2018).

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

40

Figure 2: Indonesia’s Maritime Development Plan and BRI Route

Table 2: Proposed Projects in Indonesia

Jokowi program in 2014 so that Indonesia no

longer export raw mineral materials get good

response for development of mineral purification

industry at domestic level. Some Chinese companies

are investing in upstream industry development (The

Economist, 18 January 2014). The construction of a

stainless steel factory in Morowali, Central Sulawesi

has received much attention. There are two factories

built there. Started in 2015 and is expected to be

completed in 2018. Both plants are built by a joint

Should We Worry about China? China’s Outward FDI and Aid in Indonesia

41

venture company PT Dexin Steel Indonesia, which is

45% owned by Delong Steel Singapore Projects Pte

Ltd (a subsidiary of China's Delong Holdings Ltd),

43% owned by Shanghai Decent and 12 % owned by

PT Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (The Jakarta

Post, 18 June 2017). Several joint venture agreements

also took place, namely (1) alumina smelter in

Ketapang, West Kalimantan established by China's

Hongqiao Group Ltd and Harita Group with value of

US $ 1 billion; (2) Nickel smelter in South Sulawesi

built by China's Hanking Group Ltd and Bumi

Makmur Selasar Group for US $ 500 million; (3) the

industry in Cikarang, West Java was founded by

China's Shenzen Yantian Port Group Co., Country

Garden Holdings Co. and Lippo Group with a value

of US $ 14.5 billion (Negara & Suryadinata 2018). A

widely circulated issue is the presence of workers

from China in the region and local partners are still

part of overseas china (Chinese Indonesians). The

Chinese government considers that overseas China as

all ethnic Chinese spread all over the world (Negara

& Suryadinata 2018). Moreover, in the investment

made by China not only on financing. These include

project management, equipment supplies,

construction materials and workers (Das 2018).

Concern also arises that China is building up projects

that the recipient country does not really need and

only burdening the foreign debt of the recipient

country to China (Faulder & Kawase 2018).

Policy-making processes in developing countries

are volatile, influenced by domestic political

uncertainty, changing political context processes,

changing the role of civil society, the influence of

donor countries and weak institutional capacity (Buse

et al 2005; Sutcliffe & Court, 2005). These lead to

unpredictable and sectorally predictable political and

policy assumptions rather than a grand aggregate

agenda (Holmes & Scoones, 2000; Waldman, 2005).

Donor countries and foreign investors influence

foreign policy making. Hattori (2001, 2003) sees

foreign aid as a foreign policy tool. Foreign aid is

defined as symbolic power politics between donors

and recipients. Foreign aid can be seen as a form of

giving, as a type of resource allocation, or as symbolic

domination. Foreign aid has an indirect effect as a

form of donor country domination to the recipient

country (Belle 2017). Partner countries expect the

existence of diplomatic solidarity and economic

benefits in return for foreign aid and investments

(Mawdsley 2012).

The recipient country follows the interests of the

donor country in exchange for the foreign assistance.

Viewed from the eyes of the recipient country,

economic factors are the main driving force of the

state receiving foreign aid. Because of these

economic factors, the recipient country is more

focused on the package or program of foreign

assistance offered than the political interest intentions

of the donor country (Lin 2000). However, economic

dominance without social dominance does not

necessarily make the foreign policy of the recipient

countries follow or support the policies of donor

countries (Burawoy 2012, Lovett 2009). For that

matter perception and acceptance need to be taken

into account. Here soft power plays its function. Soft

power gives rise to symbolic dominance. China

applies this symbolic dominance through four ways

(Saidi & Wolf 2011; Mawdsley 2012; Chan 2013).

First by developing a discourse that the world today

is unfair and inequitable. Globalization offers more

challenges and risks than opportunities to developing

countries. Therefore, it needs south-south

cooperation so that the agenda of international

institutions is more aligned to developing countries.

Second, China emphasizes the value of non

interference to domestic interests. Third, China

encourages more cooperation of southern countries

through investment cooperation, joint ventures,

banking, technology transfer and so on. Fourth, China

claims to be the driving force behind the emergence

of peacefull multilateralism and peaceful negotiations

on international issues. It can be said in realizing the

symbolic dominance of China utilizing the discourse

of the southern states as a sovereign state of anti-

colonization, anti-postcolonial hegemony, and

disliking the hierarchical dichotomy between north-

south. And only through south-south cooperation that

development collaboration will benefit both parties.

Traditional donors prioritize charity, social

development, and benevolence (Saidi & Wolf 2011).

While donors from these southern states offer

solidarity, mutual benefit, shared identities

(Mawdsley 2012).

However, China's soft power capability is still low

when compared to its hard power capabilities.

China’s economic power is ranked second after the

United States. China's military spending though still

far from US military spending, but Chinese military

spending is equivalent to a combination of military

spending of Japan, Taiwan and South Korea (Gilley

2011). Meanwhile, China's soft power is still low.

Kim (2010) calculated that China's soft power is

ranked 24th in 2000. Based on a survey compiled by

Pew Global Attitudes found that about 51% of

surveyed respondents believe that China will replace

the United States as a leading superpower. Based on

a public opinion poll conducted by Lowy Institute

Poll in 2006, reveals that Indonesians trust Japan

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

42

(76%) more compare to China (59%). It also reveals

that 64% respondents feel more positive to Japan as a

neighbor compare to China (58%). The survey

conducted by Center for China Studies conducted in

2014 also shows that among countries that provide

large investment in Indonesia, China is less favorable

(71%) than Japan (86%), United States (74%) and

India (72%).

This symbolic dominance makes China

economically but not politically trusted. Domination

requires the same values and interests (Gilley 2011).

In Indonesia, negative perceptions of China

(especially Chinese Indonesians) among the public

domestic and elite are still high. Based on a survey

conducted by ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute and the

Indonesian Survey Institute of 508 members of the

provincial legislature (DPRD) found that 46% believe

that Chinese Indonesians have much influence in

Indonesian politics. Fifty-five percent of the elite

surveyed objected if Chinese Indonesians held

political office. Major percentages are shown in the

Islamic parties: PAN is 82%, PPP is 81%, PKS is

73%, and PKB is 65% (Fossati & Warburton 2018).

Similar to public perception, the elite also argues that

Chinese Indonesians have a great influence in the

economy. The percentages above 60% are all. In

sequence PAN is 95%, PKS 86%, Demokrat 85%,

Gerindra and PKB equal to 83%, Golkar 73%,

Hanura 72%, NasDem 71%, PPP 67% and PDI-P

65% (Fossati & Warburton 2018).

Public perception is also unfavorable to China.

Based on the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak survey of 2017,

negative perspectives on China are largely shaped by

fears of foreign invasions from China, economic

control by China and Chinese Indonesians. China and

Chinese Indonesians are considered to have a close

relationship. As many as 48.4% of respondents stated

that China Indonesia only cares and thinks about

itself. When asked whether Chinese Indonesians still

have loyalty with China, 47.6% of respondents stated

that Chinese Indonesians are still loyal to China. In

economic terms, 62% of respondents see that Chinese

Indonesians have a big influence on the Indonesian

economy. Chinese Indonesians are considered to have

more privileges than any other citizens. The survey

found that 68.1% of respondents stated that Chinese

Indonesians have a talent for more success. Therefore

60.1% of respondents consider that Chinese

Indonesians are at least middle class and 59.8% of

respondents agree that Chinese Indonesians is richer

than other Indonesians (Herlijanto 2017).

Economic control by ethnic Chinese is

inseparable from the long history of the existence of

Chinese Indonesians. Chinese Indonesians are having

close relationship with elites, especially military's

elite. During Soeharto's era, the military's elite had a

strong position in the government. Many of them

were senior political figures. As senior political

figures, they have access to much government

projects. They are getting used to their contracts,

licenses, credits and other government projects. As

they had lack of business skills, they engaged with

Chinese Indonesian to manage their business. It was

because Chinese Indonesian could only be involved

in economy sector and because they were good on

business (Bowie & Unger 1997). Soon, personal

relationships between individual business people and

senior political figures are the dominant pattern of

business interest representation. Chinese Indonesian

offered military and indigenous politicians and

officials, cash and shares, seats on their boards of

directors, or profitable business opportunities. The

Chinese Indonesians found that their commercial

success correlated closely with how high up in the

government their patrons ranked. Those are

connected to the highest levels of income subsidies

and rent opportunities that enable them rapidly to

accumulate capital for business expansion. Soon,

Chinese Indonesians dominated the Indonesian

economy. Based on a Far Eastern Economic Review

investigation in 1998, Chinese Indonesian businesses

controlled 80% of Indonesian wealth whilst they were

only 2% of total population (Far Eastern Economic

Review 28 May 1998 cited in Purdey 2000). Chinese

Indonesians were associated with corruption. They

were targeted and victims of political and economic

nationalism sentiments in May 1998 when mass

protests in Jakarta demanded reformation and

Soeharto resignation. The riot caused many Chinese

Indonesians business closed down and they fled to

China (Yue 2000). Nineteen years after reformation

the stereotypes among Chinese Indonesians are

remained. Based on a survey by ISEAS Yusof-Ishak

in 2017, most respondents (62.4%) consider that

Indonesia will only benefit slightly from China

despite their close economic ties (Fossati, Hui,

Negara 2017).

The issue of China played a lot of political

opponents Jokowi despite the fact that China has

invested heavily and worked on infrastructure

projects in the previous presidential period. The use

of issues surrounding foreign investment by political

opponents is often found in countries with established

democracies. The political competition made the

issue shift, from what were originally industrial

relations to political contestation (Robertson &

Teitelbaum 2011). The issue is surrounding the flood

of labor from China at the level of blue colar (non-

Should We Worry about China? China’s Outward FDI and Aid in Indonesia

43

skilled workers). For example, at a cement factory in

Lebak Banten, there are rumored to be about 800 non-

skilled workers from China. In fact there are 400

workers from China employed because the industry

require special skills from them. The Minister of

Labor Hanif Dhakiri and Vice President Yusuf Kalla

has denied the rumor (Kompas 17 July 2017).

Jokowi's political opponents also wrapped up the

issue by exploiting the MoU (Memorandum of

Understanding) with China containing the

government's target to bring in 10 million Chinese

tourists until 2019. The target to bring in tourists was

then repackaged as a statement to bring in 10 million

workers from China (Kompas 3 October 2016).

The stereotypes of China and Chinese

Indonesians among the domestic public and the elite

have made Indonesia's policy towards China

pragmatic to gain many benefits and avoid direct

confrontation. At the same time Indonesia is also

trying to expand policy possibilities. Indonesia's

attitude is more to hedging. Hedging is defined as a

strategy aimed at avoiding situations where the state

is not biased to firmly define behavior such as

balancing, bandwagoning, or neutrality. Hedging

provides a space for a country to cooperate without

taking parties from one of the competing parties so

there is a high ambiguity in the direction of the

hedging country's policy.

Some time Indonesia did military display as a sign

that Indonesia is independent of China. Indonesia also

opens opportunities for foreign-owned oil exploration

companies to conduct exploration in the Natuna

islands. The Natuna Islands are in the South China

Sea and have an unexploited gas and petroleum

content. Additionally, Indonesia announced a new

naming for some of the South China Sea region as the

Natuna North Sea in July 2017. It received a response

from China. China requested that Indonesia cancel

the decision. Indonesia's Coordinating Minister of

Maritime Affairs Luhut Panjaitan said that it is

included in Indonesia's domestic realm because it is

still within the Indonesian ZEE region and not part of

the South China Sea as a whole. Therefore, China

should not intervene. Another incident was in March

2016. The Chinese ship was suspected of illegal

fishing in the Natuna islands and Minister of Marine

Resources and Fisheries Susi Pudjiastuti protested

against the action to the Chinese ambassador to

Indonesia. Attitudes to be more proactive are also

shown by the military. General Moeldoko publicly

wrote in the Wall Street Journal that Indonesia should

be firm against China in the South China Sea.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs shows friendly

attitude. The Minister of Foreign Affairs of 2014

stated that between Indonesia and China there is no

regional dispute and Indonesia took a position to use

ASEAN as a mediator of disputes in the South China

Sea. President Jokowi states the same that each side

should support the Code of Conduct of the South

China Sea and say that the nine-dashed line claimed

by China has no basis in international law (Kapoor &

Sieg 2015). This South China Sea issue also does not

get much response from the Indonesian public. This

is because Indonesia is not one of the four Southeast

Asian South China Sea claimants.

The attitude of hedging is also seen from the

attitude of Indonesia who mostly uses its position as

middle power country. Indonesia is careful not to take

sides with China or the United States. China is an

important partner in economy; meanwhile the United

States is an important partner in terms of security.

Additionally, Chinese presences in the South China

Sea and nine-dashed line claims have no direct effect

on Indonesia. This prevents Indonesia from rushing

into alignment with one party and preferring to use

ASEAN as a regional organization. Middle power

executes a strategy to take part that affects

international organizations because through

international institutions middle power can reduce the

gap with great powers (Gilley 2011, Hilliker 2010).

Middle power avoids the attitude of supporting one

party to reduce the risk of "betting on the wrong

horse" (Kuik & Rozman 2015). Indonesia currently

plays it. Gilley (2011) mentions that as a form of

response to China's rising power in the region,

Indonesia is the second ranked great power status or

major power in Asia, as well as Japan. South Korea

and Thailand are identified as middle power.

Hamilton-Hart & McRae (2015) calls Indonesia a

middle power. Based on the notion of Mares (1988),

Middle power has the ability to disrupt the system but

has no ability to change it through unilateral action.

Middle power with sufficient resources, together with

a small country in the region can affect the existing

system.

4 CONCLUSION

The number of Chinese investment and loans in

Indonesia increased rapidly during the reign of

Jokowi. This raises concerns that Indonesia is

becoming dependent on China. Instead of

banwagoning, Indonesia chose to be hedging in its

foreign policy towards China. This is evident from

Indonesia's stance on the security situation in the

South China Sea and Indonesia's stance on the Belt

Road Initiative. On the issue of the South China Sea,

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

44

Indonesia uses ASEAN as a forum to negotiate with

China. Indonesia exploited ASEAN to voice its

policies so that China can comply with the code of

conduct compiled together. With respect to the Belt

Road Initiative, no projects have been financed under

BRI's mechanism yet. In addition, the proposed

Indonesian projects that are offered are not all within

BRI's line of business. Indonesia also invited

investors from other countries to BRI and non-BRI

lines.

In the meantime, there are two things influence

the attitude of Indonesian hedging. Firstly, there are

still high public and elite stereotypes in Indonesia

against China. As a result Jokowi tends to be careful

to offer projects that are done and funded by China.

The funding project by BRI has also not been

implemented. Secondly, for the issue of the area in

the South China Sea, Indonesia is not directly

involved as a claimant country so this issue does not

get much attention from public domestic. Therefore,

Jokowi plays a role as a middle power by utilizing

ASEAN. For the Natuna region, especially the cases

of fish theft by Chinese vessels in the EEZ (Exclusive

Economic Zone) region of Indonesia, the Ministry of

Marine Affairs and fisheries often cast protests.

Response is also given by increasing patrolling of the

area in Natuna.

REFERENCES

Agosin, M dan Mayer, R. 2000. Foreign Direct Investment

in Developing Countries, UNCTAD Discussion Paper

146. Geneva: UNCTAD.

Balasubramanyan, V, et al. 1996. Foreign direct investment

and growth in EP and IS countries. Economic Journal,

106 (434): 92-105.

Bowie, A., D Unger. 1997. The politics of open economies:

Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buse, K, et al. 2005. Making Health Policy. Maidenhead:

Open University Press.

Chan, G. 2013. “Power and Responsibility in China’s

International Relations”. Yongjin Zhang, Greg Austin

(eds). Power and Responsibility in Chinese Foreign

Policy. Canberra: ANU Press.

Cook, I. 2006. Australia, Indonesia and the world: public

opinion and foreign policy, The Lowy Institute Poll

2006. Sydney: Lowy Institute for International Policy.

Crouch, H. 1979. ‘Patrimonalism and military rule in

Indonesia’, World Politics, vol. 31, no. 4, 1979, pp.

576-7.

Das, SB. 2018. “Do the Economic Ties between ASEAN

and China Affect Their Strategic Partnership?”

Perspective. Issue 2018, no. 32, 21 June 2018.

Singapore: ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute.

De Mello, L. 1999. Foreign direct investment-led growth:

evidence from time series and panel data, Oxford

Economic Papers, 51(1): 133-151.

D Faulder. K Kawase. 18 July 2018. “Cambodians Wary as

Chinese Investment Transform Their Country”. Nikkei

Asian Review.

https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Cover-

Story/Cambodians-wary-as-Chinese-investment-

transforms-their-country. Accessed 30 June 2018.

Fossati, D., Y. Hui, SD. Negara. 2017. “The Indonesia

National Survey Project: Economy, Society and

Politics”. Trends in Southeast Asia. Singapore: ISEAS

Yusof Ishak Institute.

Fossati, D. E Warburton. 2018. “Indonesia’s Political

Parties and Minorities”. Perspective. Issue 2018, no 37,

9 July 2018. Singapore: ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute.

Gabrillin, A, “Menaker Bantah Isu Indonesia Kebanjiran

Tenaga Kerja China”, Kompas, 17 July 2016

<http://nasional.kompas.com/read/

2016/07/17/12074221/menaker.bantah.isu.indonesia.k

ebanjiran.tenaga.kerja. china> Accessed 30 June 2018.

Gilley, B. 2011. “Middle Powers during Great Power

Transitions: China’s Rise and the Future of Canada-US

relations”. International Journal. 66(2): 245-264.

Hamilton-Hart, N. D McRae. 2015. Indonesia: Balancing

the United Stats and China, Aiming for Independence.

Sydney: United States Studies Centre, The University

of Sydney.

Haswidi, A. “Southeast Asia’s Foreign Debt Spirals”. FT

Confidential Research. Nikkei Asian Review. 16 July

2018. https://asia.nikkei.com/Editor-s-Picks/FT-

Confidential-Research/Southeast-Asia-s-foreign-debt-

spiralsHaswidi 2018. Accessed 25 July 2018.

Hattori, T. 2001. “Reconceptualizing Foreign Aid”. Review

of International Political Economy, 8(4): 633-660.

Herlijanto, J. 2017. “Public Perception of China in

Indonesia: The Indonesia National Survey”.

Perspective. Issue 2017, no. 89. 4 December 2017.

Singapore: ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute.

Herzer, D. et al. 2006. "In Search of FDI-Led Growth in

Developing Countries", Ibero-America Institute for

Economic Research Discussion Papers, No. 150,

Goettingen, Germany.

Hilliker. 2010. “Middle Power in Perspective: the historical

section in Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and

International Trade”. International Journal. 66(1): 183-

195.

Hilman. 2018. “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five

Years Later”. CSIS.

<https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-belt-and-road-

initiative-five-years- later-0> accessed 25 July 2018.

Holmes, T. & Scoones, I. (2000) Participatory

Environmental Policy Processes: Experiences from

North and South, IDS Working Paper 113, Brighton:

IDS

Kapoor, K. L. Sieg. 23 March 2015. “Indonesian president

says China’s main claim in South China Sea has no

legal basis”. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-

indonesia-china-southchinasea/indonesian-president-

says-chinas-main-claim-in-south-china-sea-has-no-

Should We Worry about China? China’s Outward FDI and Aid in Indonesia

45

legal-basis-idUSKBN0MJ04320150323. Accessed 30

July 2018.

Kim, H. 2010. “Comparing Measures of National Power”.

International Political Science Review. 31(4): 405-427.

Kompas, “Indonesia Siap Kerja Sama dalam Prakarsa ‘Belt

and Road’”, 16 May 2017

<http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2017/05/16/154954

01/indonesia.siap.kerja.sama.dalam.prakarsa.belt.and.r

oad>. Accessed 30 June 2018.

Kuik, Cheng Chwee & Rozman, Gilbert. 2015. Light

Hedging or Heavy Hedging: Positioning between China

and the United States. Joint Korea-US Academic

Studies.

Liddle, RW. 1985. ‘Soeharto’s Indonesia: personal rule and

political institution’, Pacific Affairs, vol. 58, no. 1, p.

78,

Lin, The-chang. 2000. The Donor Versus the Recipient

Approach: a Theoritical Exploration of Aid

Distribution Patterns in Taipei and Beijing. Lynne

Rienner Publishers.

Mares, D. 1988. “Middle Powers under Regional

Hegemony: to Challenge or Acquiesce in Hegemonic

Environment”. International Studies Quarterly. 32(4):

453-471.

Mawdsley, E. 2012. “The Changing Geographies of

Foreign Aid and Development Cooperation:

Contributions from Gift Theory”. Transactions of the

Institute of British Geographers. 37(2): 256-272.

Milanovic, B. 2002. ”Can We Discern the Effect of

Globalization on Income Distribution?”, World Bank

Policy Research Working Paper. Washington DC:

World Bank.

Morisset, J., Pirnia, N. 2001. ”How tax policy and

incentives affect foreign direct investment: a review” in

L Wells, N Allen, J Morisset, N Pirnia (eds), Using Tax

Incentives to Compete for Foreign Direct Investment:

Are They Worth the Costs?, Washington DC: Foreign

Investment Advisory Service.

Negara, SD. L. Suryadinata. 2018. “Indonesia and China’s

Belt and Road Initiatives: Perspectives, Issues and

Prospects.” Trends in Southeast Asia Series. Singapore:

ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute.

Nunnenkamp, P., Spatz, J. 2004. ’FDI and economic

growth in developing economies: how relevant are

host-economy characteristics?”, Transnational

Corporations. 31(1): 53-83.

Onyeiwu, S. 2015. Emerging Issues in Contemporary

African Economies: Structure Policy and

Sustainability. Palgrave Macmillan.

Purdey, J. 2000. Anti-Chinese violence in Indonesia, 1996-

1999. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

Robertson, GB. E Teitelbaum. 2011. “Foreign Direct

Investment, Regime Type, and Labor Protest in

Developing Countries”. American Journal of Political

Science. 55(3): 665-677.

Saidi, MD., C. Wolf. 2011. “Recalibrating Development

Co-operation: How Can African Countries Benefit

from Emerging Partners?” OECD Development

Working Papers 302. OECD Publishing.

Sutcliffe, S. Court, J. 2005. A Toolkit for Progressive

Policymakers in Developing Countries. London: ODI.

Suryowati, E. “Banyak Penerbangan Langsung, Indonesia

Diserbu Turis China”, Kompas, 3 October 2016

<http://ekonomi.kompas.com/

read/2016/10/03/145126826/banyak.penerbangan.lang

sung.indonesia.diserbu. turis.china> Accessed 30 June

2018.

The Economist, “Mining in Indonesia: Smeltdown”, 18

January 2014 <https://

www.economist.com/news/business/21594260-

government-risks-export-slump- boost-metals-

processing-industry-smeltdown>. Accessed 30 June

2018.

The Jakarta Post, January 24, 2018

Stefani Ribka, “China’s Delong to build $950m steel

factory in Morowali”, Jakarta Post, 18 June 2017

<http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/06/18/

chinas-delong-to-build-950m-steel-factory-in-

morowali.html>. Accessed 30 June 2018.

Waldman, L. 2005. Environment, Politics and Poverty: a

Review of PRSP Stakeholder Perspectives. Brighton:

IDS.

Wang, LM. 2014. China Overseas Investment: concerns,

facts and analysis. Beijing: CITIC Press.

Wang, M., Zhen Qi and Jijing Zhang. 2015. “China

Becomes a Capital Exporter Trends and Issues” in

Ligang Song et al (eds). China’s Domestic

Transformation in a Global Context. Canberra: ANU

Press.

Yue, M. 2000. ‘Chinese networks and Asian regionalism’,

in PJ Katzenstein (ed.), Asian regionalism. Ithaca:

Cornell University.

ACIR 2018 - Airlangga Conference on International Relations

46