Incorporating Self-assessment and Reflection in Writing Portfolios of

EFL Writers

Tengku Silvana Sinar

1

, Liza Amalia Putri

1

and Dian Marisha Putri

1

Faculty of Cultural Science, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia

Keywords: Writing self-assessment, Writing portfolios.

Abstract: Can incorporating self-assessment and reflection as a part of the writing process make EFL students

improve their writing? This article presents the findings of a semester-long study conducted at four

universities in Medan, North Sumatera where writing portfolio were implemented to help students

document their progress. Using pre- and post- test design, it was found that the writing performance of

students who used portfolio mainly focusing on incorporating self-assessment and reflection for their essay

writing process over a semester more increased than students who did not. The increase of writing

performance corresponded to students’ perceptions of improvement in writing. EFL writers who were

usually concerned with fixing surface-level errors (mechanics and vocabulary) rather than global errors

(organization and content), in this study, were partly concerned with global errors.

1 INTRODUCTION

To help EFL students become better and successful

writers, teachers need to help them have knowledge

and skills in assessing their own writing.

Incorporating self-assessment and reflection is part

of the writing process of successful writers.

According to O’Neill (1998), incorporating self-

assessment and reflection into the writing process is

not a new idea in the field of English composition:

composition practitioners and theorists have been

advocating it through the seventies, eighties, and

nineties, especially as portfolios have become more

popular. The literature on metacognitive activities

agrees that such exercises help students become

better writers. Encouraging students to become their

own evaluators gives them more power and control

over their writing, As Robert Probst explains, the

transfer of power to the student writers is the most

important part of teaching writing: “The

responsibility for making judgements about the

quality of their work must become the students’.

They are the ones who must feel the rightness or

wrongness of their statements, because, ultimately,

they are responsible for what they write” (76). How

about self-assessment conducted by EFL writers? It

was hypothesized in this study that EFL students’

writing performance increased over time with the

significant progress happening between pre- and

post- portfolio implementation primarily focusing on

self-assessment and reflection. The finding was

strengthened by the fact that the group not

conducting self-assessment and writing reflection

journals did not experience a significant progress

with regard to writing performance when this was

measured at the beginning and at the end of the

semester. Students’ incapability of self-assessing

was the result of their perceptions of improvement in

writing. EFL writers were usually concerned with

fixing surface-level errors rather than global errors.

However, in this study, students at four universities

in Medan, North Sumatera were partly concerned

with global errors. This study was part of a larger

research program that examined the development of

students’ writing performance through portfolio

integration in the curriculum and that was funded by

the Research Institution at University of Sumatera

Utara in the year of 2018.

Sinar, T., Putri, L. and Putri, D.

Incorporating Self-assessment and Reflection in Writing Portfolios of EFL Writers.

DOI: 10.5220/0010071412731279

In Proceedings of the International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches (ICOSTEERR 2018) - Research in Industry 4.0, pages

1273-1279

ISBN: 978-989-758-449-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

1273

2 INCORPORATING

SELF-ASSESSMENT AND

REFLECTION AND ITS

CONNECTION WITH

PORTFOLIOS

2.1 Self-assessment and Reflection

Self-assessment research has been going since the

1950s and originated within the field of Social and

Clinical Psychology (Hilgers, Hussey, & Stitt-

Bergh, 2000). The two key concepts embedded in

the notion of self-assessment are self-observation

and self-monitoring. Self-monitoring, the parent of

self-assessment, provides individuals with internal

feedback which allows them to compare the current

level of behavior with some well-recognized social

standard (Kanfer, 1975). This feedback comes

partially from observation and evaluation, which

have been shown to be key processes in affecting

change with deep-seated human behaviors (Bellack,

Rozensky & Schwartz, 1974; Cavior & Marabott,

1976).

In writing research, studies on self-assessment,

which is sometimes referred to as revision within the

writing process, began to receive attention in the late

1970s when the Flower and Hayes (1981a) model of

the composing process permeated composition

studies. This was also the exact period when

cognitivism was in vogue. The view of self-

monitoring, which belongs to the domain of

behaviorism, was out of fashion. Hence, studies of

self-monitoring were gradually replaced by studies

focusing on writing coping strategies and their

effects (Flower and Hayes, 1981b; Hayes, Flower,

Schriver, Stratman, & Carey, 1987). According to

the Flower and Hayes’s (1981a) model, revision is

one component of the cognitive writing process, and

modifying writing strategies or texts is due to the

constant evaluation and reevaluation of the text.

Nevertheless, in the 1996, Hayes proposed that a

new framework for understanding cognition and

affect in writing was needed. In Hayes’s new model,

revision was reorganized and subsumed under a new

category, reflection, which is a function that requires

writers to problem-solve and make decisions (Hayes,

1996).

In the 1990s, social constructivist theory

made it clear that all behaviors are influenced in one

way or another by the social contexts in which they

are situated (Bruffee, 1984; Grabe & Kaplan, 1996).

However, from a behaviorist or cognitivist

perspective, self-assessment is viewed as a set of

isolated acts. This view does not take into account

how individuals acquire self-assessment strategies

and under what circumstances they make use of

socially contextualized criteria to self-evaluate their

own work (Hilgers, Hussey, & Stitt-Bergh, 2000).

Consequently, studies of self-assessment that

adopted a behaviorist or cognitivist perspective have

been unable to identify ways that an individual’s

self-assessment practices could be made more

effective, thus helping an individual become a better

writer who can actively engage in the composing

process. Therefore, more research is needed on how

novice writers in an EFL context adopt self-

assessment and its impact on their writing

development.

2.2 Writing Portfolios

Since the 1990s, writing portfolios have been widely

adopted as either a large-scale writing assessment or

classroom-based assessment in various teaching

contexts in the United States. Part of the appeal for

using writing portfolios is the component of

reflection, which helps students think about what

they have achieved throughout the process of

writing individual pieces as well as the overall

portfolio construction (Hamp-Lyons & Condon,

2000; Weigle, 2002; Yancey, 1998; Yancey &

Weiser, 1997). Within Hamp-Lyons and Condon’s

(2000) theoretical framework of portfolio

assessment, the terms reflection and self-

assessment are used interchangeably although

Broadfoot (2007) argued that they do not mean the

same thing. These two terms also suggest that

students will revisit their early and interim drafts to

reflect upon their effort and progress throughout the

course of writing. For example, when teachers adopt

a showcase portfolio approach, students are usually

asked to review all papers and drafts and then select

the best ones either for display (e.g. to a future

employer) or for summative grading. Self-

assessment, as defined by Hamp-Lyons and Condon,

can help students better understand what they are

expected to compose as well as explore their own

strengths and weaknesses in writing in order to make

further improvement.

Portfolio assessment, therefore, has the potential

to create positive washback on students’ writing

(Biggs & Tang, 2003; Hughes, 2003). Traditionally,

students have been asked to write in a “one-draft,

one-reader” context (Arndt, 1993). Having received

a grade and minimal feedback from the teacher,

students may make corrections on their drafts. After

that, the learning process is supposedly finished and

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1274

students are asked to write on another topic. The

product approach to writing promotes students’

reliance on a teacher’s summative judgments rather

than helping students to self-assess their own drafts

before submission. The adoption of a portfolio

approach in EFL writing classrooms may empower

students’ active participation in self-evaluating their

own work within the writing process (Weigle, 2007;

White, 1994; Yancey, 1998).

2.3 Purpose of the Study

This study was designed as a guide for portfolio

implementation. It was hypothesized that students

benefitted their writing by enhancing their linguistic

awareness and helping them better monitor the

writing strategies they selected for composing the

portfolio entries. Process portfolios were used as a

systematic way to help students place more

emphasis on the learning process rather than the

final outcome and engage in the processes of

documenting their progress monitoring, goal setting,

reflection and self-evaluation (mastery experiences).

As part of an intervention to increase students’

writing performance, this study implemented

process portfolios to students at four different

universities in Medan, North Sumatera, Indonesia.

They are students of English department at

University of Sumatera Utara, students of English

department at State University of Medan, students of

English study program at University of Harapan, and

students of English study program at Islamic

University of Sumatera Utara.The study attempted to

answer the following research questions:

1. Can incorporating self-assessment and reflection

as a part of the writing process make EFL students

improve their writing?

2. What are students’ perceptions of the impact of

self-assessment and reflection on the improvement

of their writing?

3 METHOD

3.1 Research Design

A non-equivalent pre-test and post-test design was

used. The study was conducted at four different

universities in Medan, North Sumatera, Indonesia.

There are English department at University of

Sumatera Utara, English department at State

University of Medan, English study program at

University of Harapan, and English study program

of Islamic University of Sumatera Utara.

3.2 Participants

The participants of the treatment group were 120

fifth semester English department students of four

universities in Medan (convenience sampling) over

one academic semester (January 2018–June 2018).

A total of 158 fifth semester students who were part

of four intact classes in different universities where

portfolios have not been used served as a control

group for the study and they completed the self-

assessment and reflection instrument twice, as a pre-

test and as a post-test, at the beginning and at the

end of the academic semester.

An effort was made to identify control

classrooms who would match as closely as possible

the experimental classrooms. All teachers needed to

follow national curriculum requirements for the

development of Composition course. Therefore

control group students produced the same amount of

writing pieces throughout the semester in the same

genres (one of them is an argumentative genre) but

without following the process approach.

Experimental teachers used portfolios, while control

teachers did not.

Consent forms were agreed by teachers and

students. Confidentiality was assured and

pseudonyms were used instead of the real names of

all participants. In general, the treatment of

participants was in accordance with the ethical

standards.

3.3 Students’ Training in using

Portfolios

All experimental students received training on the

use of portfolios and on how to set goals, conduct a

self-evaluation, self-reflect and provide peer

feedback. Specific support structures were used for

training as students did not have any previous

experiences with these portfolio affordances.

Templates were used to train all experimental

students: (a) on providing peer feedback, (b) on

conducting a self-evaluation of their writing, (c) on

self-reflection by revisiting their writing piece and

providing an answer to prompts and (d) on goal

setting by describing specific areas where

improvement in their writing was needed.

To explain the use of supporting templates, some

examples for peer feedback, self-evaluation and

reflection support are provided next. The symbols

are the following:

S = spelling mistake

G = grammatical mistake

Incorporating Self-assessment and Reflection in Writing Portfolios of EFL Writers

1275

+ = have to add a word/sentence/paragraph

- = have to delete a word/sentence/paragraph

P = start a new paragraph here

C = capital letter

R = repetition

PU = punctuation

CR = consider revision.

The criteria used for conducting a self-evaluation of

students’ writing are the following:

Did I organize my essay in paragraphs?

Is there an introduction, main body and

conclusion in my essay?

Did I put adequate content in my essay?

Did I put adequate knowledge of written

genres in my essay?

Did I put adequate content in my essay?

Did I have effective paraphrasing in my

essay?

Did my essay have enough vocabulary?

Did I have problematic sentence structure

in my essay?

The prompts that were used to guide students’

reflection after completing the drafts of their writing

piece are the following:

What did you like best about your essay?

What can you improve on the next draft?

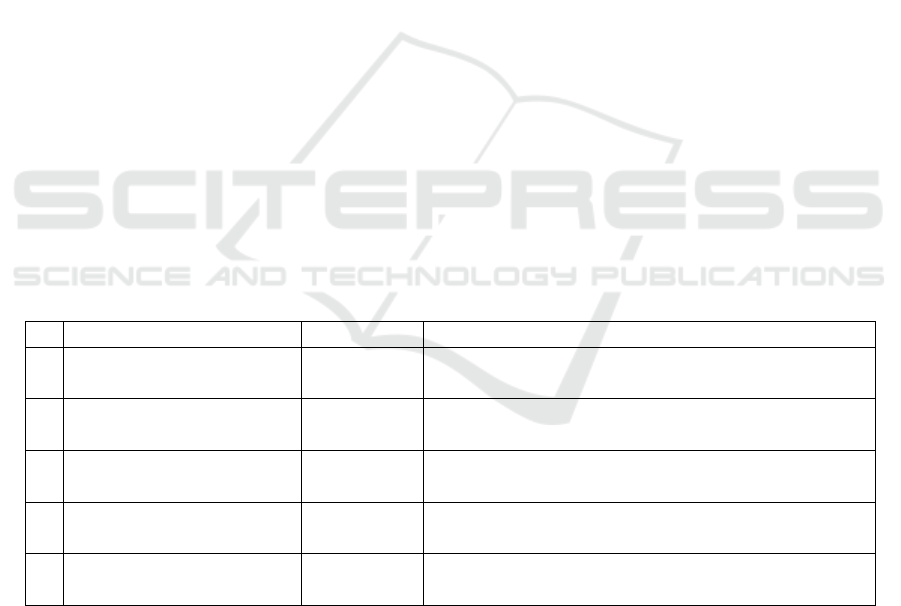

Finally, the general rubric used to grade students’

writing performance is the following:

Rubric 1 Grading students’ writing performance.

5 Exemplary 4 Understanding 3 Competent 2 Developing 1 Beginning

Focus:

The student’s

writings fit the

prompt and went

beyond with

additional

readings and

experiences that

brought new light

to the paper.

The student

wrote a paper

that followed all

the guidelines

given but did

little to add

more to the

work.

The student

covered most of

the requirements

and did so in a

way that

suggested they

understood the

prompt.

The student wrote

a paper that had

the subject, but

did not follow the

prompt or did not

meet the

requirements in

another way.

The student

did not turn in

a paper or did

not attempt to

meet the

requirements.

Development:

The student came

in to talk with the

instructor about

the paper and

took suggestions

to heart through

the rest of his

paper.

The student

came in and

talked about his

paper, but only

worked on some

of the problems

that were

noticed in the

paper.

The student may

have come in

once, but there

was at least one

rewrite created

to improve the

piece.

The student could

recognize

mistakes during

the time with the

instructor, but

was unwilling to

correct them or

work beyond the

first draft.

The student

did not turn in

a paper or did

not attempt to

meet the

requirements.

Audience:

The paper was

written in a way

that was easy to

read and was

clearly written to

benefit the correct

audience, both in

word choice and

in experiences

shared.

The work was

written in a way

that covered the

prompt and

allowed the

audience to

understand what

was being

communicated.

The audience

had difficulty

relating to the

work because of

word choice or

the way

experiences

were shown to

them.

The audience felt

alienated by the

piece because of

word choice and

experiences

shared. The

author clearly did

not take the

audience into

consideration.

The student

did not turn in

a paper or did

not attempt to

meet the

requirements.

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1276

The data was consisting of students’ self-assessment

forms and reflective journals, which were part of the

required portfolio entries. Students were asked to fill

in a self-assessment form and complete a writing

journal during the semester. In other words, self-

assessment was done retrospectively of the semester.

The self-assessment process involved students

referring back to their drafts, figuring out which

entry was the best, and justifying why they believed

it was well-written. Self-assessment forms and

reflective journal entries were collected from the

students. The reflective journal entries that were

selected for use in this study mentioned the benefits

of self-assessment and discussed them at length.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Students’ Writing Improvement by

Incorporating Self-assessment and

Reflection in the Writing Process

To better understand the progress in students’

writing performance over time, scoring was

conducted by using the rubric. Ten students from the

experimental and control groups were selected based

on the results of administration, so as to include

three students with low, three students with average

and four students with high writing performance for

each group. Students were ranked according to their

pre-portfolio implementation score on writing

performance. The three students with the lowest

writing performance scores (A, B, C), the four

students with the highest writing performance scores

(G, H, I, J) and three students from the middle of the

distribution of scores (D, E, F) were selected.

Pseudonyms were used in place of students’ real

names to facilitate the reporting of findings.

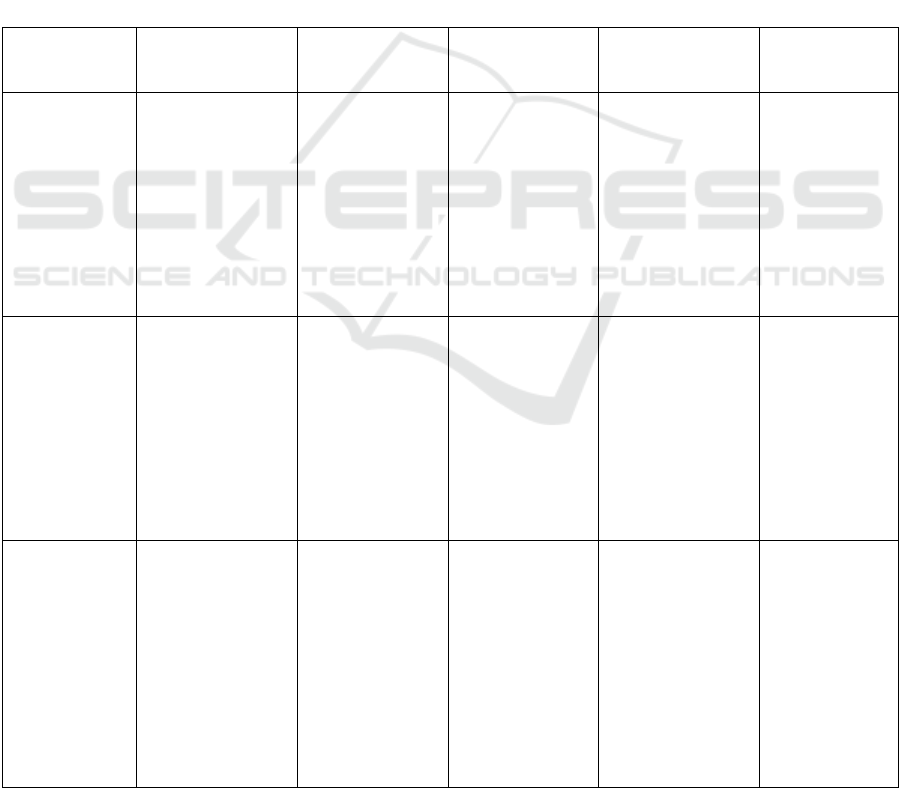

Table 1 presents students’ writing performance

(WP) scores pre- and post- portfolio implementation.

With regard to methodology, students’ writing

performance that ranged between the minimum

possible score of 3-7 was coded as ‘‘low’’. Students’

writing performance that was the score of 8-11 was

coded as ‘‘average’’. Students’ writing performance

that was higher than 11 and lower than or equal to

15 was coded as ‘‘high’’.

Table 1. Selected experimental and control group students’ writing performance scores over time

Findings showed that three experimental group

students with low scores (A, B, C) in pre-portfolio

implementation received higher scores in post-

portfolio implementation. Two out of the three

students earned the same code, the low code, while

one out of the three students did get the better code,

from the low to average code. Three experimental

group students with average scores (D, E, F) in pre-

portfolio implementation received higher scores in

post-portfolio implementation. One out of the three

students earned the same code, the average code,

while two out of the three students received the

better code, from the average to high code. Three

experimental group students with high scores (G, H,

J) in pre-portfolio implementation received higher

scores in post-portfolio implementation and one

student (I) earned the same score. All students in this

Name Experimental

Group

Control Group

Pre-portfolio

Implementation

Post-portfolio

Implementation

Pre-test Post-test

A

4 (low) 7 (low) 4 (low) 4 (low)

B

6 (low) 7 (low) 5 (low) 5 (low)

C

6 (low) 8 (avg) 7 (low) 6 (low)

D

8 (avg) 9 (avg) 9 (avg) 8 Iavg)

E

10 (avg) 13 (high) 10 (avg) 10 (avg)

F

11 (avg) 12 (high) 11 (avg) 11 (avg)

G

12 (high) 13 (high) 12 (high) 12 (high)

H

12 (high) 13 (high) 12 (high) 11 (avg)

I

13 (high) 13 (high) 12 (high) 13 (high)

J

13 (high) 14 (high) 13 (high) 12 (high)

Incorporating Self-assessment and Reflection in Writing Portfolios of EFL Writers

1277

group were in the same score code (the high code)

before and after the portfolio implementation.

The other group students, control group students,

showed different findings. The students with low

scores (A, B, C) in pre-portfolio implementation

received the same code (low) in post-portfolio

implementation. Two out of the three students

earned the same scores, and even one out of the

three students earned lower score. Three

experimental group students with average scores (D,

E, F) in pre-portfolio implementation received the

same code level (average) in post-portfolio

implementation. One out of the three students earned

lower score, and two out of the three students

received the same scores. Three experimental group

students with high scores (G, I, J) in pre-portfolio

implementation received the same code (high) in

post-portfolio implementation and one student (H)

earned lower code (from high to average).

The result of this study showed that students’

writing performance increased over time with the

significant progress happening between pre- and

post- portfolio implementation. The finding was

strengthened by the fact that a control group that did

not use portfolios did not experience a significant

progress with regard to writing performance when

this was measured at the beginning and at the end of

the semester. With regard to the interpretation of

these findings, it is important to identify some

possible explanations. Experimental teachers may

have been more open to innovative teaching

practices than control teachers. In addition, support

was provided to experimental students in the form of

training on how to use portfolios and how to engage

in portfolio processes. These are possible

explanations to the impact of involving self-

assessment and reflection in writing portfolio of EFL

writers.

4.2 Perceived Impact of Self

Assessment

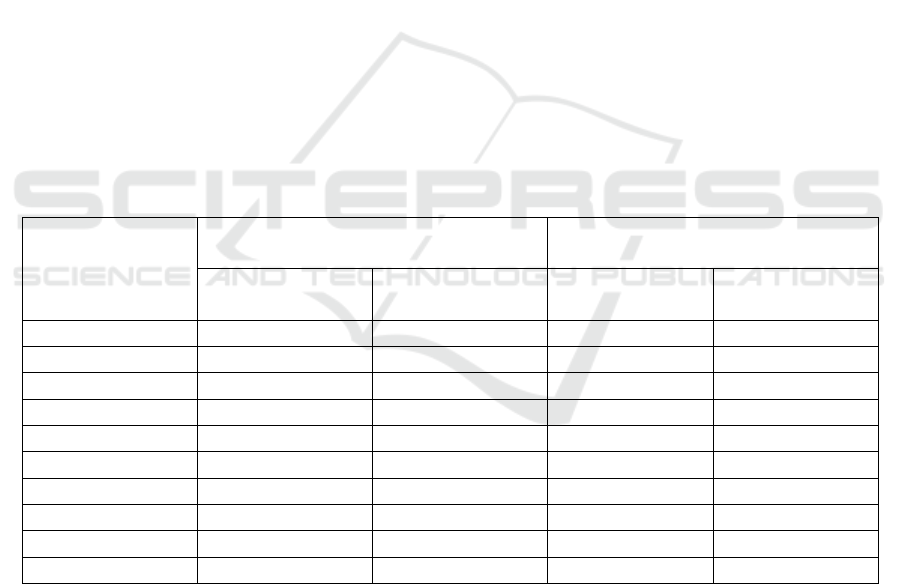

Three major answers by the students in term of the

aspects of writing they could improve further which

can be seen in Table 2 below are grammatical

mistakes, inadequate content, and lack of

vocabulary. The first aspect was to avoid

grammatical errors. The second aspect,

unpredictable, was to enrich and diversify ideas in

writing. It was surprising as this kind of mistake was

one of the global errors that EFL writers were often

not concerned about. The third aspect was to use a

wide range of vocabulary to express ideas. It is

interesting to pay attention that students usually

focused on surface-level errors such as mechanics

and vocabulary, but in this finding some students

thought revising global errors, such as content and

organization, as an area of potential improvement.

Table 2. Students’ Perception of Areas in Demand of Improvement

Categories Frequency Description

1.

Grammatical mistakes 32 Students conduct grammatical mistakes in their

written work

2.

Inadequate content 25 Students are not able to enrich and diversify

their ideas in their writing

3.

Lack of vocabulary 21 Students lack sufficient vocabulary items to

express ideas in their writing

4.

Problematic sentence

structures

12 Students use too simplistic and inappropriate

sentence structure

5.

Poor organization 10 Students put their ideas not logically and

coherently connected in their written work

Students were taught how to respond to both local

and global errors when reviewing their own drafts

and their peer drafts. It could be said that their

perceptions of improvement in writing were mainly

concerned with fixing surface level errors rather than

global errors. However, the result showed that some

students were concerned with global errors. It was

related to the previous finding regarding to the

writing improvement as the result of students having

knowledge and skills in conducting self-assessment

and getting help of reflection journals. Students

successfully applied the methods in their writing

portfolio so that they made significant progress

between pre-portfolio implementation and post-

portfolio implementation.

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1278

As a matter of fact, some students were also still

concerned with surface-level errors. There may be

reasons for this phenomenon. One of the reasons is

that students have difficulty differentiating between

the processes of revising, which concern both

content and organization, and editing, in which only

grammatical errors are paid attention. This concept

was also reinforced by any students’ teachers who

only marked grammatical errors in their essays.

Another reason students were focused more on

correcting local rather than global errors was that

students were probably incapable of revising higher-

level errors such as organization and content. It is

obvious that students needed

more training guidance

in order to self-assess global errors in their writing.

5 CONCLUDING REMARKS

The study supported that students’ writing

performance increased over time with the significant

progress happening between pre- and post- portfolio

implementation primarily focusing on self-

assessment and reflection. The finding was

strengthened by the fact that the group not

conducting self-assessment and writing reflection

journals did not experience a significant progress

with regard to writing performance when this was

measured at the beginning and at the end of the

semester. Students’ incapability of self-assessing

was the result of their perceptions of improvement in

writing. EFL writers were usually concerned with

fixing surface-level errors rather than global errors.

However, in this study, students at four universities

in Medan, North Sumatera were partly concerned

with global errors.

REFERENCES

Arndt, V. (1993). Response to writing: Using feedback to

inform the writing process. In M. Brock & L.

Walters (Eds.),Writing around the pacific rim (pp. 90-

114). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Bellack, A. S., Rozensky, R., & Schwartz, J. (1974). A

comparison of two forms of self- monitoring in a

behavioral weight reduction program. Behavior

Therapy, 5, 523-550.

Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2003). Assessment by portfolio:

Constructing learning and designing teaching. In P.

Stimpson, P. Morris, Y. Fung, & R. Carr

(Eds.), Curriculum, learning and assessment: The

Hong Kong experience. Hong Kong: Open University

of Hong Kong Press.

Bruffee, K. (1984). Collaborative learning and the

“conversation of mankind”. College English, 47, 635-

652.

Flower, Linda, and John R. Hayes. “Cognitive Process

Theory of Writing.” College Composition and

Communication 32 (1981): 65–87.

Hamp-Lyons, L. & Condon, W. (2000). Assessing the

portfolio: Principles for practice, theory and

research. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Hilgers, T. L., Hussey, E. L., & Stitt-Bergh, M. (2000).

The case for prompted self-assessment in the writing

classroom. In J. B. Smith & K. B. Yancey (Eds.), Self-

assessment and development in writing: A

collaborative inquiry (pp. 1-24). Cresskill, N.J.:

Hampton Press.

Kanfer, F. H. (1975). Self-management methods. In F. H.

Kanfer & A. P. Goldstein (Eds.), Helping people

change: A textbook of methods (pp. 309-355). New

York: Pergamon.

Lam, R. (2010). The Role of Self-Assessmentin Students’

Writing Portfolios: A Classroom Investigation. TESL

Reporter 43, (2) (pp. 16-34).

Nicolaidou, I. (2012). Can Process Portfolios Affect

Students’ Writing Self-Efficacy?. International

Journal of Educational Research (pp. 10-22).

O’Neill, P. (1998). From the Writing Process to the

Responding Sequence. Council of Teachers of

English Journal (pp. 61-70).

Probst, Robert E. “Transactional Theory and Response to

Student Writing.” Anson 68–79.

Weigle, S. C. (2007). Teaching writing teachers about

assessment. Journal of Second Language

Writing, 16(3), 194-209.

Incorporating Self-assessment and Reflection in Writing Portfolios of EFL Writers

1279