Students’ Responses to the Use of Authentic Material in a General

English Class

Eka Rahmat Fauzy

Balai Bahasa, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Jl. Dr. Setiabudhi No. 229, Bandung, Indonesia

ekarahmat2@gmail.com

Keywords: Authentic Materials, Integrated Skills.

Abstract: This research is aimed to identify how students respond to the use of authentic materials in a General English

class. This research is based on qualitative case study design employing observation and focused group

interview to obtain the data. The results of data analysis suggest that students perceived both benefits and

challenges from the use of authentic materials in integrated skill based teaching. Therefore, it can be

concluded that the proper use authentic materials will be responded positively in an integrated skill based

class. Nonetheless, it is strongly recommended that the employment and implementation authentic materials

in teaching and learning process have to be prepared well since careless selection of authentic materials may

demotivate students, instead of encouraging them to understand the lesson.

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of authentic materials in language classrooms

has become a prominent topic over a couple of

decades, and with the rapid development of

technology, especially internet and multimedia, the

access to such materials has never been easier

(Erbaggio et al., 2012; Huessien, 2012; Mudra,

2014). Studies and practices in college English

teaching in recent decades have underlined the

importance of integrated skills involved in language

learning, and the design of the course itself and

related classroom activities have begun to receive a

lot attention in language teaching (Lin, 2004). To

support that purpose, the use of authentic materials

can be considered as a useful strategy in developing a

unit of material to implement the integration of

language skills in the classroom (Nunan, 1991;

Harmer, 2007), including in General English class.

Although some practitioners argued the idea, many

language teachers (Shrum and Glisan, 2000;

Kilickaya, 2004; Khaniya, 2006) believe that

authenticity has proved its beneficial role in language

teaching and the popularity of the use of authentic

materials in diverse settings, learning objectives, or

tasks has increased since the last decade.

Considering the significance of facts mentioned

above, a research on such real-life materials

integrated in all language skills has value to enhance

the richness and flexibility of college English or other

language courses and to provide useful examples or

guidance for other practitioners or researchers in

selecting and employing authentic materials in

integrated skill based activities because careless use

of authentic materials, rather than encouraging

students to understand the content, may demotivate

students (Lin, 2004; Harmer, 2007).

Some of selected studies related to the use of

authentic materials in language skill teaching suggest

that authentic materials enable learners to interact

with the real language and content rather than the

form and learners positively respond and feel that

they are learning a target language as it is used outside

the classroom (Khaniya, 2006; Baghban and

Ambigapathy, 2011; Tra, 2011; Nasta, Machmoed

and Manda, 2013; Alijani, Maghsoudi and Madani,

2014). Moreover, authentic materials are claimed

substantial to motivate learners because they are

intrinsically more interesting or stimulating than

artificial or non-authentic materials, and they can

provide students with up-to-date knowledge, expose

them to the world of authentic target language, and

bring the real world into the classroom (Peacock,

1997; Gilmore, 2007; Tra, 2011; Al Azri and Al-

rashdi, 2014). Even though, those previous studies

have been able to present a significant contribution

from the use of authentic materials in language

learning, many of them were grounded on general or

conceptual context of the topic, or on a particular area

848

Fauzy, E.

Students’ Responses to the Use of Authentic Material in a General English Class.

DOI: 10.5220/0007176408480853

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 848-853

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

of language skills, such as on speaking skill (Tra,

2011) and listening skill (Nasta, Machmoed and

Manda, 2013). Therefore, this research was

conducted in a class of a general English program

which usually covers, centres, and gives equal

attention to the four main language skills, as reflected

in actual English communication (The University of

Western Australia, no date; Far, 2008; Lamri, 2016).

Basically, authentic material can be considered as

normal and natural language used by native or

competent speakers of a language (Harmer, 2007). In

academic context, authentic materials can be

anything, including song, English movie, English

radio program, and many other videos of native

speakers speaking English which can be found easily

in students’ daily lives, that is available to the

language teacher, but was not produced for language-

teaching purposes since there could be differences to

textbook materials in aspects of linguistic

competence, pragmalinguistic competence, discourse

competence, and implications for materials design

(Gilmore, 2007; Robinson, cited in Tra, 2011; Nasta,

Machmoed and Manda, 2013; Al Azri and Al-rashdi,

2014). Table 1 below shows a comparison between

authentic and non-authentic materials, showing that

the characteristics of authentic materials reflect a true

nature of language use in real-life communication

(Miller, cited in Firdaus, 2014).

Table 1: The comparison of authentic and non-authentic

materials.

Authentic Materials

Non-Authentic Materials

They are produced for

real life communication

purposes.

They are specially

designed for learning

purposes.

They may contain false

starts, and incomplete

sentences.

The language used in them

is artificial. They contain

well-formed sentences all

the time.

They are useful for

improving the

communicative aspects

of the language.

They are useful for

teaching grammar.

In line with those points, the use of authentic

materials in integrated-skills approach is relevant as

both prepare students for real-life situations, making

connections between life and learning (Lin, 2004).

Thus, it is obvious that any of the four skills can be

developed best in association with other language

skills. At first, in the real practices, listening is not

simply a one-way process of receiving audible

symbols, but it is usually an interactive process

involving meaning negotiation, turn taking,

discussion, as note-taking and writing in response to

what is listened. Similarly, reading is commonly

interactive and includes higher-level thinking skills,

self-reflection, and inference. Further, from a

communicative and pragmatic view of the language

teaching, oral production occurs in a variety of

contexts or genres, such as conveying or exchanging

specific information, engaging in small talks, or

maintaining social relationships. The last skill,

writing, can be a process involving the writer, written

or oral texts, and other writers or readers. Thus, it is

obvious that any of the four skills can be developed

best in association with other language skills. Tajzad

and Ostovar-Namaghi (2014) suggested that

segregating language skills in learning activity may

help learners to comprehend language as knowledge

well, but it will not enable them to use their

knowledge in actual communication. They further

asserted that the integrated-skills approach can trigger

simultaneous use of skills, enhance learners’

motivation and self-confidence, save class time, and

provide reflection time.

In ELT, the more students see and listen to

comprehensible input, the more English they acquire,

notice, or learn (Harmer, 2007). This input takes

many forms; teachers’ utterances, audio materials,

textbooks, podcasts, video, etc., and moves in a circle

in which one’s output will return to be an input after

exposed by some processes of evaluation,

modification, and feedback from teachers, other

students, and the student himself or herself. Further,

this cycle is incorporated in Harmer’s basic

methodological models for teaching receptive and

productive skills.

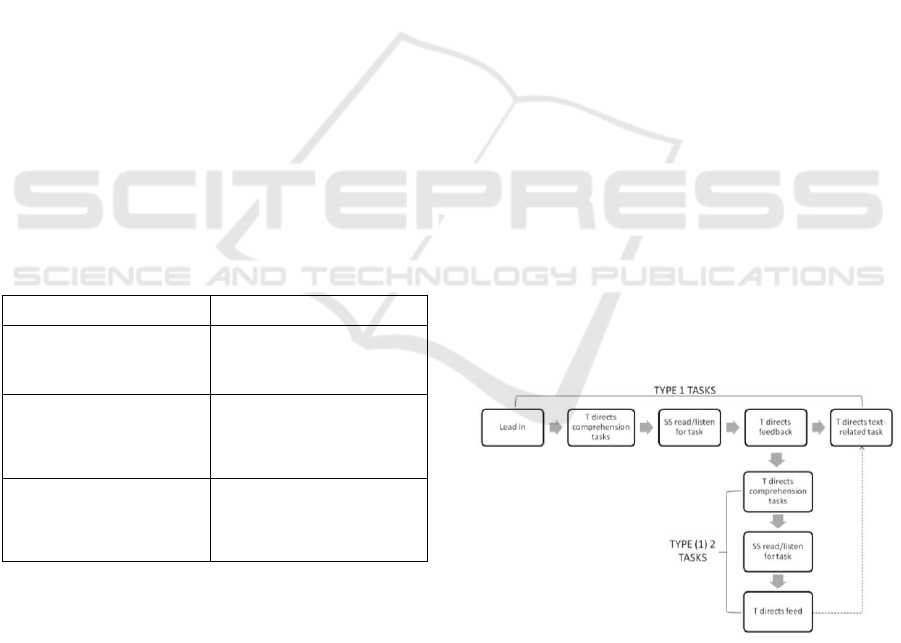

Figure 1: A basic methodological model for teaching

receptive skills.

Students’ Responses to the Use of Authentic Material in a General English Class

849

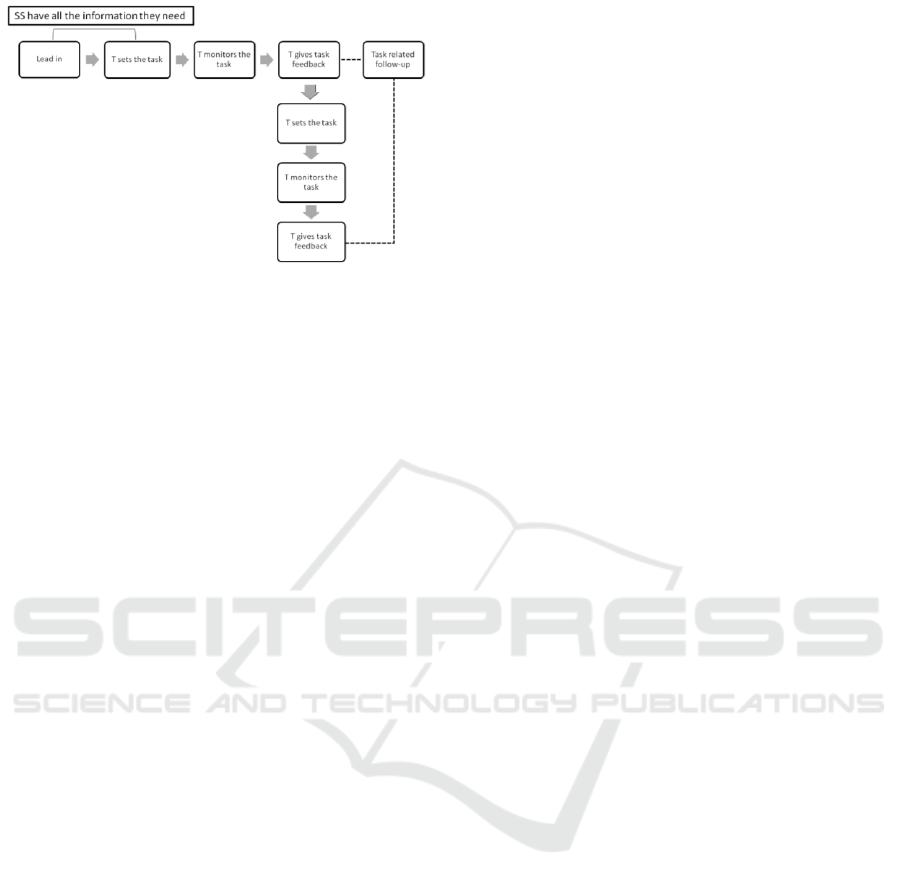

Figure 2: A basic methodological model for teaching

productive skills.

Figure 1, on the one hand, shows that teaching

receptive skills starts with a lead in where students are

engaged in the topic and their schema or pre-existent

knowledge is activated. When students are ready,

teacher sets some kind of comprehension task, and

then directs feedback, and gives follow-up activity.

The comprehension cycle is repeated and then teacher

involves students in text-related tasks. On the other

hand, it can be seen from Figure 2 that the success of

Harmer’s model for teaching productive skills

generally relies on the way teacher organizes the tasks

and how to respond the students’ work.

Generally, to develop a unit of material to practice

the integration of language skills in the classroom,

consideration is necessary on the principles of

authenticity provided in the material for the students,

continuity that reflects the chain activities people do

in the real-life situation, real-world focus to stimulate

applicable sense of the lesson in their daily life, and

students’ language focus exposed to the language as

a system and asserting them to be encouraged to have

self-monitoring-and-evaluation skill (Nunan, 1991).

To support integrated skill based teaching, the use of

authentic materials can be considered appropriate at

post-intermediate level attributed to the fact that at

this level, most students master a wide range of

vocabulary in the target language and all of the

structures (Guariento and Morley, cited in Kilickaya,

2004; Khaniya, 2006). Nonetheless, authentic

materials can be used by lower level students if the

tasks given are well-designed to help students

understand it better (Guariento and Morley, cited in

Kilickaya, 2004; Khaniya, 2006; Harmer, 2007).

According to McGrath (cited in Al Azri and Al-

rashdi, 2014) there are eight criteria to be

considered when choosing appropriate authentic

texts; relevance to course book and learners' needs,

topic interest, cultural fitness, logistical

considerations, cognitive demands, linguistic

demands, quality, and exploitability. Further, to

prevent demotivating effect on students from careless

use of authentic materials (Harmer, 2007), the

selection process should meet learners’ age, level,

interests, needs, goals, and expectations (Oguz and

Bahar, cited in Baghban and Ambigapathy, 2011). In

addition, some other criteria should be taken into

account, including the relevance to syllabus and

learners’ needs, intrinsic interest of topic/theme,

cultural appropriateness, linguistic demands,

cognitive demands, logistical considerations, and

exploitability ( McGrath, cited in Alijani, Maghsoudi

and Madani, 2014). By this way, authentic materials

can motivate students and give them more stimulation

in learning a language.

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research is a qualitative case study that involves

an in-depth examination of a few people in the natural

setting with multiple interactive and humanistic

methods. Furthermore, this study is not only able to

disclose explicit behaviour, but also unveil tacit

behaviour of the respondent, but it was limited by

time and activity, and researcher collected detailed

information using a diversity of data collection

procedures during a maintained period of time (Berg,

2001; Alwasilah, 2002; Stake, cited in Creswell,

2003).

The target population was 14 students from two

intermediate General English classes. To obtain the

data, there were two types of instruments employed

in this research; classroom observation to develop an

understanding of how students responded over the

course and focused group interview eliciting the main

information for the study. The observation

particularly focused on students’ responses to the

materials, such as students’ eagerness or reluctance to

take part in class activities. In this study the

researcher contributed as the teacher and acted as

participant observer of the study. Engagement in the

setting permits the researcher to hear, see, and

experience reality in natural setting. Further, by

means of focused group interview, a large amount of

information can be released in a comparatively short

period of time and it also allows the researcher to

observe interactions among participants, which are

not observable in individual interviews (Anglea,

2009). Besides, the questioning process in the

interview enables the researcher to explore into the

minds of the population and coherently gauge their

perspectives on issues being raised throughout the

interviewing process.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

850

The data collected from the classroom observation

were documented into observation and interview

sheets, classified, and interpreted (Alwasilah, 2002).

The whole data was then categorized and analysed

using coding method as code in qualitative inquiry is

most often a word or short phrase that symbolically

assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing,

and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-

based or visual data, including interview transcripts,

participant observation field notes (Saldana, 2008). In

the coding process, the responses are based on four

aspects; the integration of reading, listening,

speaking, and writing activities, the use of culinary

program video, the use of materials from English

course book, and the use of materials from Non-

English course book. A range of score; 1 is bad, 2 is

fair, 3 is good, 4 is very good, and 5 is excellent, is

used to categorize the quality of students’ responses

during the observation and interview.

3 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The result of data analysis from the observation and

focused group interviews demonstrated that students

overall perceived both benefits and challenges from

the use of authentic materials in integrated skill based

teaching. The data of students’ responses on the use

of authentic materials were collected and combined in

a table encoded with four aspects responded as

presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Distribution of students’ responses.

Category

/

response

Language skill

and skills

-

integrating

activities

Authentic

video

English course

book

Non

- English

course book

Excellent

21%

36%

29%

36%

Very

Good

36%

28%

29%

30%

Good

29%

29%

21%

29%

Fair

14%

7%

21%

5%

Bad

0%

0%

0%

0%

In general, Table 2 presents high percentages of

positive responses, referring to good, very good, and

excellent criteria indicated from scores 3-5 given by

the students. Further, the positive responses were

granted by more than 85% of the respondents to three

aspects; language skill and skills-integrating

activities, the use of pictures from the internet and the

culinary program video, and the use of non-English-

course-book materials. Though there were, still, a few

participants considering those four aspects tedious

(indicated from fair criteria), with the highest ratio on

the use of materials from the course book, there is no

indication on Table 2 above that participants

expressed dissatisfaction (represented by bad criteria)

on all aspects surveyed.

Further, the interview gives additional

information related to the use of authentic materials

and the integration of skills during the class and as

expected, the students took turn and supplement each

other responses during the interview; something that

may not appear in individual interview (Anglea,

2009). Most of the students agreed that they enjoyed

the activities since they were able to use English in

the practically actual communication context. The

video was taken from a culinary program on the

internet which is certainly intended for real-life

communication, not for language-teaching activities

(Robinson, cited in Tra, 2011; Nasta, Machmoed and

Manda, 2013; Miller, cited in Firdaus, 2014).

In fact, the integration of skill-based activities was

not very obvious for the students as they seemed to

set their whole focus on the activities. For example,

when observing the pictures given, some students did

not notice that they integrate speaking and listening

skills as they took turns giving opinions. Moreover,

the activity actually involves writing skill as some of

them took notes on what they were discussing. The

discussion was also enjoyable for most of the students

as they could share their ideas, make interactions with

each other, and compare the results of their discussion

with the reading text in the course book. Certainly,

the comparison integrated the result of students’

discussion involving speaking, listening, and writing

skills and their reading skill. It can be noticed that the

integration of both the main and the accessorial skills,

such as grammar and pronunciation, prompted by the

use of authentic materials reflects a form of

communication comparable to the actual one (Tajzad

and Ostovar-Namaghi, 2014).

In addition, the use of culinary program video

retrieved from the internet is also considered effective

as it could attract students’ attention and could

motivate them to be more active during the activity.

This condition supports the perception that authentic

materials can be a motivating force for learners and

can encourage them to learn better (Peacock,

1997; Gilmore, 2007; Tra, 2011; Al Azri and Al-

rashdi, 2014; Tajzad and Ostovar-Namaghi, 2014).

Such notion can be seen from students’ facial and

verbal expressions as they were watching the video

and their lively participation during discussion by

giving opinion, implication, and prediction related to

Students’ Responses to the Use of Authentic Material in a General English Class

851

the content of the video. Several students also

responded that the video stimulated them to try the

foods reviewed in the video, while others mentioned

that the video provided remarkable information that

they have not acquired before. Overall, all students

responded that from the video they could learn about

how English is used in the ‘real world’, which in this

case is dealing with food review, vocabularies related

to food ingredients, tastes, and cooking procedures.

However, some problems are still found either in

the activities integrating the language skills or in the

use of the video as an authentic material. This

condition can be implied from the lower percentages

existing in the table. It can be explored further from

the observation and interview that due to different

pace of language development and proficiency of

students, some of them tended to be more active than

others during the integrated skill activities. Besides,

even though most students understood general

information given in the culinary program video, they

still found difficulties dealing with the details. Some

students mentioned that it was due to vocabularies

considered unfamiliar for the students or the noise

produced in the video background, or simply because

the talking speed of the host or the narrator of the

program is above what students can comprehend.

Such conditions are truly among some common

concerns related to the use of authentic materials in

the classroom (Harmer, 2007; Al Azri and Al-rashdi,

2014), and therefore, instructor’s prompts and

guidance were still necessary to assist the students

and encourage their motivation.

4 CONCLUSIONS

There are many situations in which we use more than

one language skill, and for this reason alone, it is

valuable to use authentic materials to support the

integration of the language skills. Moreover, this

study demonstrates that students will give positive

responses as the authentic materials are selected

properly based on their needs. Above all, integrating

the skills means that teacher is working at the level of

realistic communication, not just at the level of

vocabulary and sentence patterns. Realistic

communication is the aim of the communicative

approach and it can be actualized by the use of

authentic materials.

Aside from the benefits verified in this research, it

is strongly recommended that practitioners

employing and implementing authentic materials in

integrated skill based activities make appropriate

preparation for the use of authentic materials in ELT

as careless selection of authentic materials may

discourage students, instead of encouraging them to

understand the lesson. It is suggested that the

materials selected is reviewed to ensure that they are

suitable for the students need and potential problems

that may arise can be altered through some strategies

during the instruction. Additionally, the result also

implied a need of development steps for the course

book; one of which by adopting authentic materials

considered more attractive for the learning process

and genuine to real-life practices.

REFERENCES

Alijani, S., Maghsoudi, M., Madani, D. 2014. ‘The Effect

of Authentic vs. Non-authentic Materials on Iranian

EFL Learners’ Listening Comprehension Ability’,

IJALEL, 3(3), pp. 151–156.

Alwasilah, A.C. 2002. Pokoknya Kualitatif. Bandung:

Pustaka Jaya.

Anglea, K.A. 2009. Rediscovering Purpose: The Power of

Reflective Inquiry as Professional Development.

Cardinal Stritch University.

Al Azri, R.H.,Al-rashdi, M.H. 2014. ‘The Effect Of Using

Authentic Materials In Teaching’, International

Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 3(10), pp.

249–254.

Baghban, Z.Z.V., Ambigapathy, P. 2011. ‘A Review on the

Effectiveness of Using Authentic Materials in ESP

Courses’, English for Specific Purposes World, 10(31).

Berg, B.L. 2001. Qualitative Research Methods for the

Social Sciences. 4th edn. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Creswell, J.W. 2003. Research Design: Qualitative,

Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2nd edn.

California: SAGE Publications.

Erbaggio, P. et al. 2012. ‘Enhancing Student Engagement

Through Online Authentic Materials’, The IALLT

Journal, 42(2), pp. 27–51. Available at:

http://www.iallt.org/iallt_journal/enhancing_

Far, M.M. 2008. ‘On the Relationship between ESP and

EGP: A General Perspective’, English for Specific

Purposes World, 7(1(17)), pp. 1–11.

Firdaus, M. 2014. The Use of Authentic Materials in

Promoting Vocabulary in ESL Classroom. Universiti

Teknologi Mara.

Gilmore, A. 2007. ‘Authentic materials and authenticity in

foreign language learning’, Language Teaching, 40(2),

p. 97.

Harmer, J. 2007. The Practice of English Language

Teaching. 4th edn. London: Longman ELT.

Huessien, A.A.A. 2012. ‘Difficulties Faced by Iraqi

Teachers of English in Using Authentic Materials in the

Foreign Language Classrooms’, Al-Fatih Journal, (50),

pp. 22–39.

Khaniya, T.R. 2006. ‘Use of Authentic Materials in EFL

Classrooms’, Journal of NELTA, 11(1–2), pp. 17–23.

Kilickaya, F. 2004. ‘Authentic Materials and Cultural

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

852

Content in EFL Classrooms’, The Internet TESL

Journal, X(7).

Lamri, C.E. 2016. ‘An Introduction to English for Specific

Purposes (ESP)’. Abou Bekr Belkaid University.

Lin, H. 2004. ‘An Integrated-skill Approach and Response

to L2 Writing in College English Course’, College

English: Issues and Trends, 1, pp. 71–88.

Mudra, H. 2014. ‘The Utilization of Authentic Materials in

Indonesian EFL Contexts : An Exploratory Study on

Learners ` Perceptions’, International Journal of

English Language & Translation Studies, 2(2), pp.

197–210.

Nasta, M., Machmoed, H.A. and Manda, M.L. 2013. ‘The

Effect Of The Use Of Authentic Materials On Students

’ Perception And Achievement In Teaching Listening

Comprehension’. Available at:

http://pasca.unhas.ac.id/jurnal/files/a3514d1e4e90bcac

d086e7c4a759da41.pdf.

Nunan, D. 1991. Language Teaching Methodology: A

Textbook for Teachers. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Peacock, M. 1997. ‘The effect of authentic materials on the

motivation of EFL learners’, ELT Journal, 51(April),

pp. 144–156.

Saldana, J. 2008. ‘An Introduction to Codes and Coding’.

Available at:

https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-

binaries/24614_01_Saldana_Ch_01.pdf.

Shrum, J.L., Glisan, E.W. 2000. Teacher’s handbook:

contextualized language instruction. 2nd edn. Boston:

Heinle & Heinle.

Tajzad, M., Ostovar-Namaghi, S.A. 2014. ‘Exploring EFL

learners’ perceptions of integrated skills approach: A

grounded theory’, English Language Teaching, 7(11),

pp. 92–98.

The University of Western Australia (no date) What is the

difference between General English and English for

Academic Purposes? Available at:

https://ipoint.uwa.edu.au/app/answers/detail/a_id/1530

/~/difference-between-general-english-and-english-

for-academic-purposes (Accessed: 3 February 2018).

Tra, D.T.T. 2011. ‘Using authentic materials to motivate

second year English major students at Tay Bac

University during speaking lessons’. Available at:

https://www2.gsid.nagoya-

u.ac.jp/blog/anda/files/2011/08/55-do-thanh-tra-viet-

nam.pdf.

Students’ Responses to the Use of Authentic Material in a General English Class

853