Representation of Putin’s Identity in Time:

An Ambiguous Partiality

Mochamad Aviandy

Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, West Java, Indonesia

m.aviandy@gmail.com, aviandy@ui.ac.id

Keywords: U.S. Presidential Election, Identity, Tata Pembermaknaan, Media.

Abstract: Two main candidates in the 2016 U.S. presidential election were Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. In this

election, news about foreign intervention, especially Russia, was so massive. One of the forms of foreign

intervention that can be analyzed is by dismantling an edition of Time Magazine that is published exactly a

month prior to electoral vote. This edition presented Vladimir Putin on its cover. This selection was certainly

without agenda. To decode the meaning behind it, the author used an analysis of Tata Pembermaknaan by

Barthes (1990). The author analyzed the cover through a visual analysis of cultural studies approach. This

method analyzed reader exclusivity perspective, an image of aging Putin, and relationship between the U.S.

presidential election and visual color and typeface on the cover. The research concluded that representation

of Putin in Time indicates a partiality of American media towards Russia even though on the other side there

is contestation towards Russian power represented by Putin.

1 INTRODUCTION

To discuss about how the identity of Russia’s

president –Vladimir Putin—is being constructed is

not easy since Putin’s Identity is very complex and

never single. If we are to explore Putin’s identity, we

need to see several identities that can be attributed to

this president of Russia. He can be identified as the

former Russia’s prime minister, former member and

the head of KGB, a skilful Judo athlete, or even a

national awakening figure for the Russian Federation.

These various identities are of course due to his

position as the President of Russia (1999 - 2008; 2012

- present) and how he is represented in media.

Putin’s identities, which are constructed by

media, have very distinct features compared to

identity construction of the Russia’s first president

after the collapse of Soviet Union, which is Boris

Yeltsin. Yeltsin constructs an image of Russia as a

new state, based on democracy, a friend to western

world, and a state that contradicts everything related

to the totalitarian of Soviet Union (Gidadhubli, 2007).

However, it is known that Putin’s branding

strategy contradicts to Yeltsin’s. Putin utilizes mass

media to highlight his branding pictures, yet behind

that he administers a terrorizing government for

Russians. Putin utilizes his power as the president to

control his photographs circulated by state owned

news agencies. Since his ruling period, the

government censorship institution revives after its

closing when USSR collapsed.

Through the state owned news agencies, Vladimir

Putin often presents some photographs accompanied

with a piece of news that reflect Putin’s perspective

or pro-Russian discourse. The news circulated from

these news agencies will always be an editorial from

a single perspective, which is the government’s

perspective. Therefore, the photographs published by

the state owned news agencies, for instance, RIA

Novosti and RT become problematic because it

becomes the formation of Putin’s individual cult. The

research by Sanja Bjelica suggests that the

photographs published through media in Russia

attribute Putin with a heroic and even male-machismo

persona. In contrast, western media depicts Putin as a

feminine figure (Bjelica, 2014). An image of Putin

that loves to explore his body by chess-baring or

swimming out in an open space is read as an

objectification of his body likewise women are being

objectified in visual scenes. Putin positing himself as

a macho-man is instead seen by western media as a

feminine side being hidden.

In this article, the author will analyze identity

construction of Putin through a cover of Time.

Photography is the main avenue to build one’s image

580

Aviandy, M.

Representation of Putin’s Identity in Time: An Ambiguous Partiality.

DOI: 10.5220/0007171305800585

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 580-585

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

(Sontag, 1977). Putin’s image that he constructs

through Russian media due to its strict and controlled

censorship impacted to the image constructed by

foreign media. The selected edition is the October

10

th

, 2016 copy. The corpus is selected because it is

the most ‘original’ copy circulated closest to where

the editorial is so that the cover is free from

censorship. In visual analysis of cultural studies, a

visual—photography, painting, advertising—cannot

be taken out of context. The analysis puts an image as

a text that has a social and historical context. In

addition, an image cannot be separated from the

publishing factors, such as the place it is published

and the audience it targets (Van Leeuwen and Jewitt,

2000)

The Asia-Pacific edition has a different cover with

the one disseminated for its exclusive subscriber. The

special subscriber is marked by a visual sign

“Subscriber Only” at the top of the cover. The article

aims to discuss the presented image of Putin through

the visual and its textual narration (the accompanying

article). The narration of Putin that is shifting as the

US presidential election begins, the author believes,

has particular reasons that can be explored further.

The author analyzes the corpus with Barthes’s

studium-punctum method of analysis (1990) and a

visual analysis of cultural studies by Van Leeuwen

and Jewitt (2000). The research aims to see the

meanings underlying in the Time’s cover edition

October 10

th

, 2016 by dissecting the cover details.

2 METHODS

This study use stadium punctum approach and

photography analysis method in analysing Putin

representations. There is a significant deference

between representations of Putin in Russian Media

and in the US media. From several photos of Putin in

Russian media, the constructed image is always

associated with populism, nationalism, and a

dictatorial government (Foxall, 2013). The

photographs published by the state owned news

agencies, such as RT, RIA Novosti, Sputnik, ITAR-

TASS, have undergone a filtering and selection

process by the Ministry of Communications and Mass

Media of the Russian Federation, whose authorities

includes deciding if a news can be published or not.

What is interesting is that Time magazine does not

construct a similar narration. This is actually a result

from different portrayal of Putin in the west/the states.

Putin is depicted as a bad –sly man and even a person

that hides his feminine side in his masculinity

branding (Bjelica, 2014).

One of the western or the U.S. magazines is the

Time. This magazine uses American journalism

perspective, employs no censorship, and has no

relation to the Russian government. However, within

the period of January-October 2016, it always

portrays Putin within the discourse of masculinity,

nationalism, populist and a strong leader similar to

what Russian media have been constructing. This

might be due to the context of the U.S. political year

as it is the year of the U.S. presidential election. The

2016 US presidential election cannot be separated

from issue of populism that is constructed by both

Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. Interestingly, the

redaction chosen to accompany the October 2016

edition is “Russia wants to undermine faith in the U.S.

election. Don’t fall for it” and in the cover is also a

figure of Putin smiling. The contradiction between

the headlines with the photograph will be explored

further in this article through stadium-punctum

analysis by Roland Barthes and the cultural studies

approach of visual analysis.

In Camera Lucida, Barthes explains two

approaches usually used in photography, which are

studium and punctum. Barthes has discussed

photography in The Photographic Message and

Rhetoric of the Images. An apparent difference is in

its research objects. In The Photographic Message,

Barthes focuses its research on pictures published by

press, whereas in Rhetoric of the Images, pictures of

advertisements in magazines become the focus. In

these two essays, Barthes makes visible how

mechanism in photography is formed, from a picture

as an object to its ‘a reader’. A picture generates a

meaning that aligns with what the object would like

to convey, which Barthes defines as denotative

meanings – literal meaning (Halley, 1982). In

Camera Lucida, Barthes sees that understanding a

picture requires several processes including what

definition of a picture is, how the meaning of the

picture works, how the picture is interpreted, both

literally and figuratively, by its spectators (Sentilles,

2010). The literal-figurative / connotative-denotative

interpretations are what Barthes further discusses in

Camera Lucida.

Barthes’s tata pembermaknaan process in this

article will be accompanied by ideology reading of an

object so it becomes myth as Fiske and Hartley offers

in Key Concept in Communication and Cultural

Studies (O’Sullivan, 1994).

Representation of Putin’s Identity in Time: An Ambiguous Partiality

581

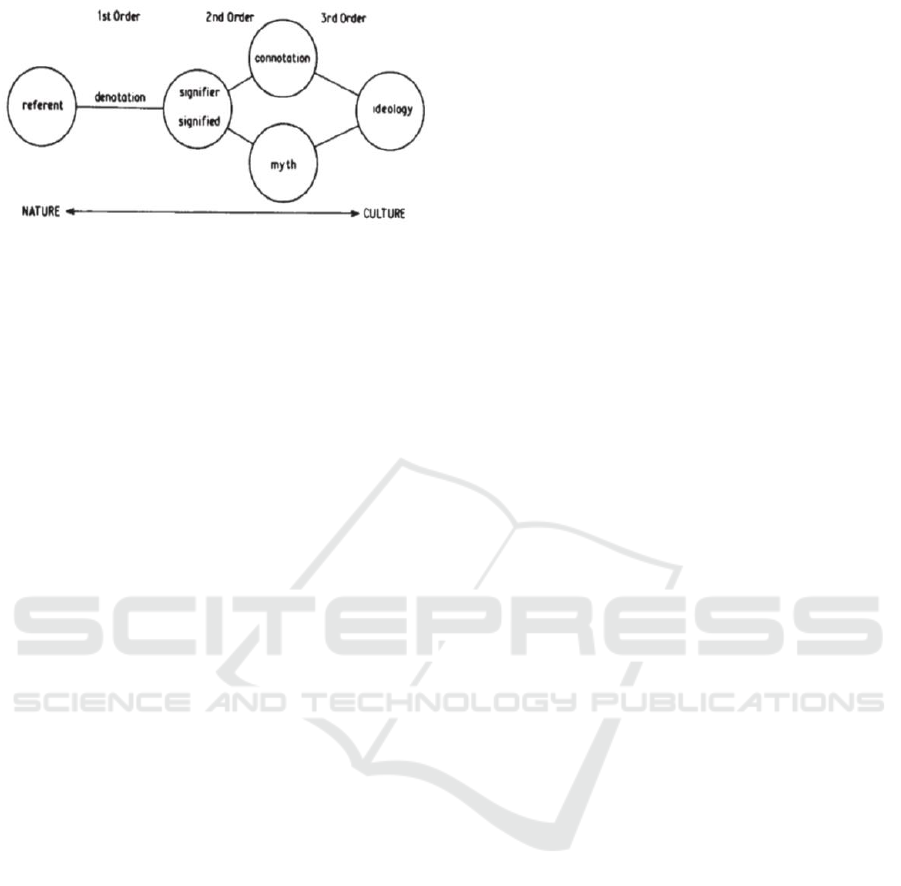

Figure 1: Processes of Signification by O’Sullivan

(O’Sullivan, 1994).

Figure 1 summarizes the emphasis of Barthes’s

studium and punctum method. The first stage is

denotation or what Fiske-Hartley and Saussure call as

signification. The second stage is connotation that

will be followed by ideology stage. The last stage

happens when the interpretation is read with the

analysis of the cultural discourse and values within

society (O’Sullivan, 1994).

Ajidarma (2000) in his research Kisah Mata:

Fotography antara Dua Subjek: Perbincangan

tentang Ada discusses how a photograph is seen from

the interpreting subject’s perspective. Ajidarma sees

that a picture is not value-free. There is something

behind a photograph that functions as visual

representation, for example, the way reading a

photograph as a form of existence, a photograph as a

part in making sense of the world, and the human

position in reading a photography work, including the

techniques in taking a photograph, for instance, the

use of black and white, color texture and lens

projection. The key in dissecting a photograph is in

the photograph’s details reading (Ajidarma, 2000).

Ajidarma’s research supports the author’s

argumentation in this research which is there is

representation, there is branding, and there is another

interpretation in the Putin’s photograph selected as

Time’s cover.

Besides that, the author also reads the cover

through a visual analysis of cultural studies by Theo

Van Leeuwen and Jewitt. According to Handbook of

Visual Analysis, in analyzing an image, there are

some elements that need to be put into consideration.

First, an image certainly contains public’s perception

and its own history. Second, an image cannot be

analyzed without considering its production,

distribution, and consumption in which the meanings

are fluid and changing accordingly. Third, an image

will always be entitled to the social process that

constructs its ‘story’ and what the image presents.

Fourth, in observing an image, there is visual

subjectivity from its reader. Therefore, there is no

‘neutrality’ within an image (photograph / painting /

poster).

In the following discussion, the author will

analyze every part of Time’s cover based on the

categorization of the meaning of each detail.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Exclusivity of the Special Edition of

Time

Before getting into the Putin’s face analysis, the

author will analyze the phrase ‘subscriber copy not

for sale’ on top of the cover.

Time uses this phrase to explain that this edition

is an exclusive edition for its subscribers, who will get

the copy if they choose to subscribe at least a year

including the expensive shipping fees from the US. In

studium sense, it just represents the subscriber edition

only, while if it is analyzed through punctum

approach, we can see a meaning of exclusivity. It

conveys an exclusivity which represents a certain

group of readers; the class it belongs to, it’s interest

in the US editorial, high income community from the

assumption that only upper-middle class who is able

to subscribe and has a mastery of English. These

levels are ideological, containing puntum element

related to its consumer’s social class.

When we approach the cover through the visual

analysis of cultural studies by Van Leeuwen and

Jewitt, the analysis cannot be taken out of values and

norms within the society since Time has a wide

distribution. The Time’s cover has its own historic

narration in the society. Since we understand a picture

through the visual analysis of cultural studies, the

picture is interrelated with social and historical

values, and the perspective of the society it targets

(Van Leeuwen and Jewitt, 2000). The emphasizing of

‘subscriber only’ is no longer neutral since it has a

subjectivity value, which is an identity of ‘loyal

reader’ that has been built by Time as a mechanism to

classify its readers. Visually, the location in which

‘subscriber only’ is placed—exactly on top of

TIME—also put a defining emphasize on exclusivity

of the cover.

This aligns with punctum explanation of a

photograph, even though it concentrates on a certain

details, its understanding is also an interpretation of

the whole photograph. Puntum reading does not pay

attention to the photographer’s purpose; instead it

requires a reading on a certain detail of the

photograph as an object that represents a particular

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

582

detail in it, related to values in the society, which is

exclusivity.

On the other hand, if we pick Time in the

newsstand, we will get a copy without the phrase. The

three levels of exclusivity will vanish. In the context

of visual analysis of cultural studies, how a certain

image is placed, either in private space, exclusive

space, or public space, has to be called into question

in the process of analysis (Van Leeuwen and Jewitt,

2000). When Time decides to differentiate one

edition—subscribers copy and retailer copy, the cover

as a representation becomes more valid. This

distinction between the two copies certainly has

historical and social rationale. The neutrality within

the picture has vanished by the time decides to have a

significant distinction on its cover.

The studium element from ‘subscriber only not

for resale’ is simply a depiction of a subscriber

exclusive edition, while the punctum element of the

phrase is the exclusivity for official subscribers over

common customer. Those who get the subscriber

copy seemingly get the same exact copy as in the US

edition without any censor. This argument is based on

others editions, such as World edition, African edition

and European edition in which the editorial narration

will be the same since it is from the same editor. The

distinction can be found simply in the cover (Hall,

2013). The analysis indicates that the US edition

signified with the phrase “exclusive for subscribers”

even though the subscribers are in another

hemisphere, for instance, Indonesia, shows a

hegemonic position in which if we subscribe to Time,

we—as a subscriber—are co-opted and seen as

though we have to accept the Time perspective of its

Americanism and censor free cover. This conclusion

comes from the understanding of studium, punctum,

and ideology from the image’s particular detail

“subscriber only not for resale.” Exclusivity, mastery

of English, and the position as a subscriber in

Indonesia that receives the US copy, not the

Asia/Indonesia copy, which is free from

Asian/Indonesian editorial filter generate a meaning

that subscribers in Indonesia are forced to read the US

copy of this edition.

3.2 Representation of Russia through

Colors

The background of the cover—bright red around

Putin’s face gradually subsiding to a darker color of

red to even black—has a certain meaning that can be

analyzed. By its studium, this background color can

be interpreted simply as a color variation. The

accentuation of the red color near Putin’s face can

artlessly be read as a device to make his face

appearing clearly, while the darker accent in the top

part of the cover is due to TIME’s red typeface that

can be seen easily if the background is dark or black.

If we punctum-approach the background, we are

presented with more meanings. For Russians, the

color red is closely associated with beauty (Mikheev,

2013). Red is frequently used in relation to the state,

for example, “Red Bear”, “communist” state, “Red

Square”, and “Red Army”. Initially, Russian

vocabulary krasnij has beauty denotation but it

undergoes a semantic change in which it shifts its

meaning to Red (the Russian Dictionary,

http://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/enc2p/258886).

Therefore, Russia is identical with Red color. The

accentuation of red around the figure of Putin can be

interpreted as an argument that Putin is a part of the

redness, which is a part of Russia. According to

Handbook of Visual Analysis, an image/picture/

photograph is related to historical context and social

discourse constructed by it. The Time’s emphasis on

the color of red and the figure of Putin is in order to

put more emphasis that Putin is Russia. Next, the

trademark writing of TIME put at the top of the cover

is red surrounded by black. This can indicate that this

edition feels like showing a dominant red color—a

color that is identical with Russia and later navigates

Putin’s identity as the representation of Russia.

3.3 Construction of Putin’s Image as

an ‘Aging’ Leader

The next stage of analysis is the analysis of Putin

photograph in the cover. The photograph is Putin

smiling, without any of his teeth showing. It shows

clearly the receding hairline and wry smile. In the

dichotomy of western media and Russian media,

there is a significant differentiation in the brands of

Putin’s identity construction. In the western media,

the constructed discourses on Putin identity are as a

bad man, seducer/tempter/teaser, intruder of the

stability of western countries, and a feminine

representation behind his macho narration (Bjelica,

2014). This contradicts the identity of Putin

constructed by Russian media which is a figure with

the quality of machismo, strong, economy builder,

and a ‘father’ to the Russian nation (Bjelica, 2014).

Putin figure on the cover is put with a darkening

red background. The denotative meaning is artlessly

a smiling man; no matter who the figure is—a

president or anyone else—the denotative meaning

being communicated is simply a man smiling.

Through the analysis of Barthes’s studium-punctum,

we could decode another underlying meaning behind

Representation of Putin’s Identity in Time: An Ambiguous Partiality

583

this photograph of smiling Putin. By its studium

analysis of the photograph, it shows Putin smiling

signifying Putin is in the state of happiness. Putin

wearing suit and tie depicts an elegant figure, likewise

the politicians in the U.S. The discourse of American

politicians needs to be disclosed as a way to

understand a photograph/picture/image in the cultural

studies approach presented in Handbook of Visual

Analysis. In this approach, the targeted social context

of a represented photograph/picture/image has to be

put into consideration. Here to fore, the argument

behind Putin wearing suit and tie needs to be analyzed

and elaborated since if Putin appears in another

clothing, for example, shirt or T-shirt, the image of

him as a politician will not appear as strong.

In this stage, if we understand the punctum

element of the picture, we will convey more

underlaying meanings. The first thing is Putin’s hair.

The element of his receding hairline can be

interpreted as Putin getting older. The photograph

clearly portrays his hair loss on top of his head, while

the hair on the sides of his head can still be observed.

This confirms Bjelica’s argument in which Putin, in

western/the U.S. media, is not depicted as a perfect

figure as in Russian media. Putin is portrayed with

weaknesses. While Bjelica argues that the attenuation

of Putin’s figure articulates through hidden feminine

side, the author suggests that the attenuation is

encoded through his aging figure. Putin is not

impeccable, macho, and strong because he seems

getting older in this edition.

Time wants to portray Putin as a president that is

no longer in his youth. Besides the receding hairline,

what the cover puts more emphasis on are clear

wrinkles in his forehead and temples. Denotatively,

these wrinkles are the signifier that an individual has

naturally been growing older. In understanding its

studium, even though the wrinkles could be covered

though photo editing, Time instead exhibits them

explicitly. Time wants to portray Putin just the avenue

that he is, in studium perspective Time is a weekly

that it is, without any editing at all. Dismantling

details of a photograph, including angle, lens

projection, face lines portrayal, and make up details

are important parts in a photography analysis

(Ajidarma, 2000). Certainly, with this argument, the

detail exhibition of Putin’s photograph cannot be left

alone.

Through punctum approach, based on Ajidarma’s

detail focusing argument and Bjelica’s discourse

analysis, we could dismantle different meanings from

this photograph with wrinkles. The wrinkles are

emphasized under an intention that Putin is a figure

who is not immune to time. With this portrayal, the

Time’s readers are expected to be more relaxed. The

tendency related to Putin photograph, similar to the

photographs of Russian leaders commonly published

by state-owned news agencies in which to present

portrayal of the leaders who always look young and

strong without any aging indicator is a phenomenon

that does not change from the communism era of

Soviet Union to today’s Russian Federation. With the

exhibition of the wrinkles, on his both temples and

forehead, an image of old Putin is explicitly observed.

The power over Russia he has is expiring, considering

his old age.

When the edition published, Putin is already 64

years old whereas the first time he was elected as the

President of Russia, he was only 47 years old. It is

also an interpretation that young figure for Putin

image is no longer relevant. Russian news agencies,

such as RT and RIA Novosti, always circulate elegant

photographs of Putin and do not highlight the clear

aging reflecting on his body, which are poles apart

with what the Time’s cover depicts. The portrayal of

aging Putin, relating it to the issue of the US

presidential election during which the edition is

published, basically resembles a portrayal of one

candidate, which is Donald Trump. Interestingly,

with the cover of this edition, Time seemingly

navigates its readers to linkages between Putin and

Trump, mainly from a figure of aging elderly male

figure.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the analysis in each stage, we can clearly

see a discourse of Putin as a figure representing

Russia and an old man identity. Although it is not

explicit, the visual analysis of this cover suggests a

partiality to a certain party, which is Republican

Party—Donald Trump. Mainstream media—in this

case is Time—is found to have a pro-Trump

tendency. However, the partiality is not explicitly and

obviously stated. It is very smooth and subtle in

articulating its partiality to Trump. Through its Putin

presenting cover, which is published exactly a month

prior to electoral vote, Time appears as one of the

media that is subtle to convey its partiality to Trump

and Putin.

One of the avenues of Time’s partiality to Putin-

Trump that has been decoded thorough stadium-

punctum analysis is the depiction of a figure—aging,

white, conservative—conformable to Donald Trump

figure. How an aging figure of Putin still able to

intervene the democratic administration constructs a

meaning that Putin—an old man can interfere the

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

584

U.S. Government. Therefore, Time seemingly

suggests that a proper figure worthy to vote by the

U.S. citizens is a Putin-like figure, which is depicted

to be able to interfere foreign party and intervene

foreign government, and basically becomes an

antithesis of democratic government who, when the

edition is published, is still running the

administration. In this edition, the subtle

representation of the government—Democratic

administration—Barrack Obama—Hillary Clinton—

appears weak and not decent for the U.S. so it is not

appropriate to vote the democrats. This is proven by

the Trump’s victory as the elected President of the

U.S. and the massive victory of Republican Party in

the senate.

REFERENCES

Ajidarma, S. G., 2000. Kisah Mata: Fotografi Antara Dua

Subyek: Perbincangan Tentang Ada. Galang Press.

Jakarta.

Barthes, R., 1977. The Photographic Message, Hill &

Wang. New York.

Barthes, R., 1990. Camera Lucida, Hill & Wang. New

York.

Bjelica, S., 2014. Discourse Analysis of the Masculine

Representation of Vladimir Putin (Thesis), Department

of Political and Social Sciences, Freire Universitas

Berlin. Berlin.

Hall, E., 2013. 19 Puzzling Differences Between “Time”

Magazine U.S and International Covers, (Online)

Retrieved on 28 Mei 2017 from:

https://www.buzzfeed.com/ellievhall/19insert-word-

here-differences-between-time-magazine-us-

and?utm_term=.taKx60745d#.ysaJob9d5V.

Foxall, A., 2013. Photographing Vladimir Putin:

Masculinity, Nationalism, and Visuality in Russian

Political Culture. Geopolitics. 18(1), pp.132-156.

Gidadhubli, R. G., 2007. Boris Yeltsin’s Controversial

Legacy. Economic and Political Weekly. 42(20).

Halley, M., 1982. Review: Argo Sum. Diacritics: The John

Hopkins University Press Journal. 12(4).

Mikheev, A., 2013. Red, White, Blue: Color Symbolism in

Russian Language, (Online) Retrieved on 2 Oktober

2017 from

https://www.rbth.com/blogs/2013/11/14/red_white_bl

ue_color_symbolism_in_russian_language_31727.htm

l.

O’Sullivan, T., 1994. Key Concept in Communication and

Cultural Studies, Routledge. London.

Sentilles, S., 2010. The Photograph as Mystery:

Theological Language and Ethical Looking in Roland

Barthes’s Camera Lucida. The Journal of Religion.

90(4).

Sontag, S., 1977. On Photography, Picador Publisher.

London.

Van Leeuwen, T., Jewitt, C., 2000. Handbook of Visual

Analysis, Sage Publications. London.

Representation of Putin’s Identity in Time: An Ambiguous Partiality

585