The Translation of Iltifat Verses: An Analysis of Translation Ideology

Mohamad Zaka Al Farisi

Department of Arabic Education, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Indonesia

zaka@upi.edu

Keywords: Person deixis, translation ideology, iltifat.

Abstract: The Holy Qur’an has iltifat (reference switching) stylistics containing the transition of a person deixis

to another person deixis that refers to the same entity. This kind of stylistics becomes a specific issue

in translation because it has the potential to present an unacceptable translation. This research is

oriented towards translation as a cognitive product with content analysis design. The research data was

chosen purposively in the form of Qur’anic verses containing the variation of person deixis transition

in iltifat stylistics and their translations. The findings of the study report that the translations of the

verses in the UMT’s translation are oriented to TL (target language) such as transposition,

amplification, linguistic amplification, reduction, etc. This means that the UMT’s translation has a

strong domestication tendency in handling the iltifat verses.

1 INTRODUCTION

The word deixis, etymologically, is derived from the

Greek, deiktikos, which means to show or to point

out or to indicate (see Huang, 2014). Later, the term

is used to refer to a word that has alternate

references, depending on when or where the word is

spoken. Deixis is a universal linguistic phenomenon.

Every language has a unique deixis system. This

happens because every language has its own rules

with diverse cultural backgrounds. This distinction

has certainly created a separate issue in translation.

It can be said that a precise understanding of the

deixis of a language in some way determines the

success of the translator in understanding a text.

In Arabic, words such as

(he),

(you),

(me), and the like are deictic because the references

can be alternated. For example, the reference

(he)

contained in the sentence (He is a dean) can

be known certainty once it is known who, where,

and when the sentence is spoken. He refers to John

if it is John; he refers to Rudy if the sentence rferes

to Rudy; and so on. Thus, the reference of a deictic

word can be identified, among other things, by

looking at the situation of speech.

Second person deixis (you) in Arabic, for

example, can produce various counterparts in the

Indonesian language. For example the sentence

, among others can be translated (1) Apa yang

kamu baca? (What do you read); (2) Apa yang Anda

baca? (What do you [more polite] read); (3) Apa

yang Bapak baca? (What do mister read). The verb

(read) covers second person deixis (you).

However, the realization of the translation in

Indonesian may vary, depending on the position of

the spokesperson. If the speech partner has a power

continuum (see Eggins, 2004) equal to the speaker,

then kamu (you) is the proper diction; if the speech

partner is a newly known speaker, anda

(you, more

polite form) is more proper; if the speech partner is

higher than the speaker, Bapak (Sir) is certainly

more appropriate. The choice of the word Bapak in

the example (3) occurs because of the consideration

of the modesty maxim with the social deixis aspec.

According to Huang (2014), there are generally

three categories of deixis. One of them is person

deixis that is associated with the understanding of

the partner of speech about the category of person or

role assignment in a speech event. The person

category is then classified into first person, second

person, and third person. In Arabic, there are 14

person deixis that are grouped according to the

aspect of the genders ( ); numerals ()

including single (), dual (), and plural ();

and syntactic functions ( ). Based on its

syntactic function, the person deixis is divided into

three categories: (1) , the person

deixis that occupies the accusative position, (2)

, that occupies the nominative position, (3)

, that occupies a genitive position

because of idlafat –is coupled with a noun, and (4)

260

Farisi, M.

The Translation of Iltifat Verses: An Analysis of Translation Ideology.

DOI: 10.5220/0007165602600265

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 260-265

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

, that occupies a genitive position due

to the existence of certain prepositions.

The categorization of person deixis in some

levels helps the translator in identifying the

reference of a person deixis. The person deixis ,

for example, refers to third person, female, singular,

and occupies a nominative syntactic function;

refers to second person, female, singular, and

occupies a nominative syntactic function; refers

to first person, male/female, plural, and occupies a

nominative syntactic function; and so on.

Each language has its own uniqueness because

of the existence of cultural concepts (see Al

Farisi, 2017). The language of the Qur’an is

unique and is characterized by many language

styles. One of the stylistics of the Qur’an is the

existence of iltifat. The realization of iltifat in the

Qur’an can be the transition of a person deixis to

another person deixis occurring in one or more

verses of the Qur’an in which these two persons

deixis refer to the same entity. Normally, the

person deixis shift in iltifat has a specific purpose.

According to Al-Badani et al. (2015a), the

transition from a third to a first person deixis in

the Qur’an presents a pragmatic glorification.

Mirdehghan et al. (2012) report that the use of

iltifat in the Qur’an aims to present exaggeration,

reproach, reminding majesty and power,

upbraiding, and annunciation.

In translation, the shift of a person deixis

element in an iltifat verse is a complex issue, not

only for target audience but also for translator

(see Al-Badani et al., 2015b). The complexity is

due to the existence of two different persons

deixis referring to the same entity in one or more

verses of the Qur’an. Yusuf Ali, the translator of

The Holy Quran, for example, ignores the

reference shift that occurs in the translation of the

iltifat verses (Al-Badani et al., 2014). Yusuf Ali

translates the person deixis element in the iltifat

verses by using literal technique. The abundance

of literal technique often results inadequate

translations because of the differences of SL and

TL, both in language and cultural aspects. Hence,

translations of iltifat verses must fulfill aspects of

accuracy, clarity, and naturalness (Larson, 1984).

1.1 Iltifat Stylistics in the Qur’an

One of the style, which directly or indirectly,

influences a translator’s point of view in

understanding the Quran messages is iltifat. Among

the Arabs, iltifat is nothing new. Many Arabic poets,

both classical and contemporary, use the iltifat in

their works. A classical Arabic poet, Umruul Qais,

for example, relies heavily on the use of iltifat in his

poetry.

In the tradition of Arabic literature, iltifat is

seen as a style that has a literary value. It is even

seen as the courage of the Arabs in speaking (see

Al-Atsir, n.d.: 4). This is due to the emotional

rhyme categorization of risk, and therefore

potentially cause misunderstanding in the

utterance. Not surprisingly, the Qur’an also

contains many verses with iltifat style. The

realization of the Qur’an style is among others in

the form of shifting from a person deixis to

another’s person deixis. These two persons deixis

commonly refer to a same entity that is already

mentioned in the verse. The shift of person deixis

in the iltifat verses must have a certain purpose.

The shifting of person deixis, for example from

first person deiksis to second person deixis or vice

versa, aims to attract reader attention or to

eliminate the saturation that might occur due to

the use of the same person deixis (Al-Akhdhari,

2013; Hidayat, 2009). According to Hubal (2015:

23-25), the iltifat style of the Qur’an generally

aims to beautify a speech by bringing shifts from

one speech style to another speech style. The

intention is, among others, to honor, to criticize,

or to attract interlocutor. Accordingly, the deixis

system in the iltifat is unique because it presents

two persons deixis that refer to one entity in a

speech with a particular aim and purpose.

Iltifat has certainly become a complex issue in

translation. Related to this, in facing a text, a

translator must ponder the following three questions:

(1) What does the SL text writer say? (2) What does

the SL text writer mean? (3) How did the SL text

writer reveal it? This implies that translating a text

does not simply transfer word for word from SL into

TL, but it also diverts the intention of the SL text

writer. For that purpose, a translator need to look at

the SL stylistics in conveying the writer’s messages.

It may be, for example, that the SL text writer

reveals his messages in iltifat.

2 RESEARCH METHOD

This study is a descriptive study with content

analysis design. It is oriented to translation as a

cognitive product. The focus of the study is on the

elements of the person deixis contained in the

Qur’anic verses. The translation unit revolves

around the levels of words, phrases, clauses, and

sentences contained in the iltifat verses along with

The Translation of Iltifat Verses: An Analysis of Translation Ideology

261

its translation in Al-Qur’anul Karim Tarjamah

Tafsiriyah by UMT (Ustad Muhammad Thalib) in

handling Qur’anic iltifat verses. The data was

collected based on the book Uslubul Iltifat fil

Balaghatil Qur’aniyyah and researcher’s

encyclopedic knowledge of the Qur’anic iltifat

verses. The sampling was done purposively based

on the criteria of the verses that contain the shift

from a person deixis to another person deixis. The

object of research is related to the translation

ideology tendency of Al-Qur’anul Karim

Tarjamah Tafsiriyah.

3 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1 Tendency of Translation Ideology

The term translation techniques refers to practical

steps in handling translation units on a micro-

level, whether in words, phrases, clauses, or

sentences. In practice, the handling of a

translation unit may require more than one

translation technique. Therefore, sometimes,

translators use a couplet procedure that combines

two translation techniques, a triplet that combines

three translation techniques, and a quartet that

combines four translation techniques at once. On

the translations of the iltifat verses, the UMT’s

translation exposes various translation techniques

in various translation procedures. The following

table shows the various translation techniques

used in the UMT’s translation of the iltifat verses.

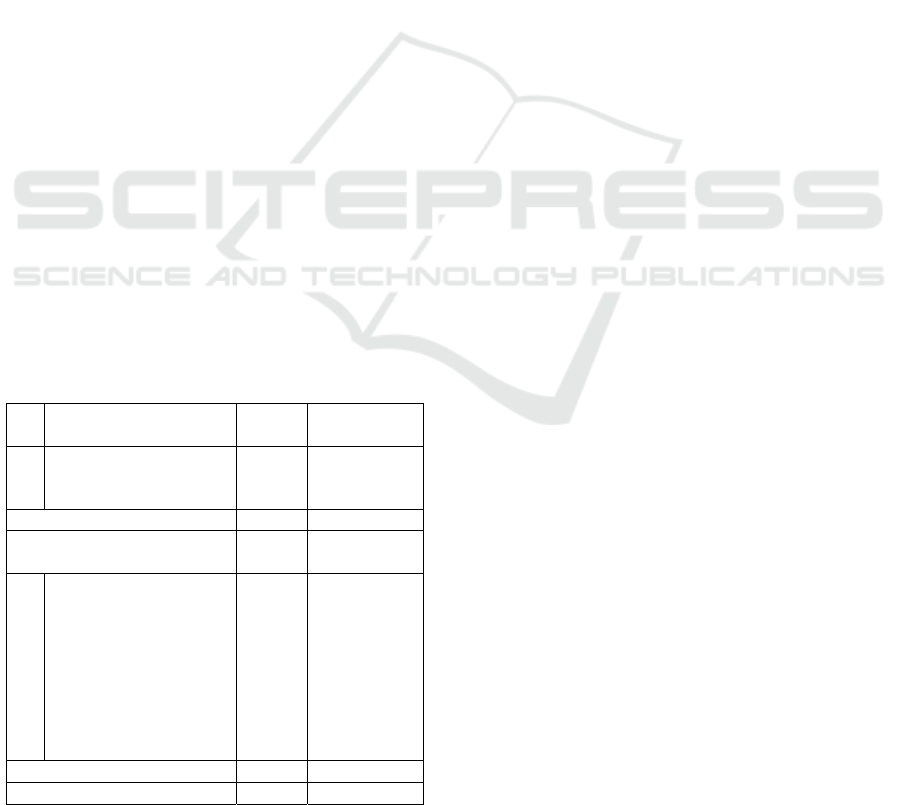

Table 1: The Use of Translation Techniques.

Nr

Translation

Techniques

Freq

Translation

Ideology

1

SL Orientation

1. Literal

2. Borrowing

138

16

Total 154

Percent (%) 38.2 Foreigniza-

tion

2

TL Orientation

1. Transposition

2. Amplification

3. Linguistic

amplification

3. Reduction

4. Modulation

6. Generalization

7. Particularization

64

54

48

47

22

10

4

Total 249

Percent

(

%

)

61.8

D

omestica-tion

In a translation process, the proper use of

translation techniques is intended, for example, to

present the correspondence of the translated texts

and the source text. The problem is, as Osimo

(2013) says, presenting comparability often leaves

the issue to (un)translatability. The

(un)translatability is repeated with the problem of

ease and luxury that often occurs in translation. In

translation, there is a ‘mandate’ that must be

conveyed (read: translated) to the target reader.

The occurrence of discrepancies and luxuries may

be intended to present the subtlety and the textual

nature of the text (see Al Farisi, 2017b).

The issue of (un)translatability is common

because of different lingual and cultural aspects

present in SL and TL, including those related to

style in the SL that do not have equivalent in the

TL. The (un)translatability dictates the difference

parameters of two languages and cultures for a

certain period of time and in a certain point of

view. Therefore, the main problem in translation

is the difficulty of bringing SL and TL

equivalence on the micro level, either at the level

of words, phrases, clauses, or sentences.

If equivalence can be presented, every element

of language that has been aligned is still open to

bring up various interpretations. Therefore, once

again the process of matching is actually the main

activity in translation. It is in this connection that

Larson (in Esfandiari and Jamshid, 2012) says

that translating means (1) studying lexicon,

grammatical structure, communication situation,

and cultural context of the SL text; (2) analyzing

the SL text to find its meaning; (3) revealing the

equivalent meaning by using lexicon, grammatical

structure, and appropriate cultural context within

the TL.

Although SL and TL are different, the

universal nature of language and cultural

convergence allows the correspondence of bias to

materialize in translation. However, in the

practice of translation, bringing the equivalence of

the SL message in TL is not an easy matter. It is

often difficult for translators to find a

correspondingly acceptable equivalent in TL. The

difficulties of presenting correspondence are

reflected in the aspects of the gaps between SL

and TL, both in language and cultural dimensions.

In practice, gaps necessitate adjustment, while

adjustment requires a strategy that, among other

things, manifests in the application of various

translation techniques. According to Molina and

Albir (2002), translation techniques are the steps

applied to analyze and to classify the presence of

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

262

correspondences in translated text. The

application of translation techniques must

naturally be logical, functional, and contextual,

since the application of translation techniques will

have an impact on the micro unit of a text and

translation result.

There is no doubt that the acceptability of

translation is, among other things, determined by

the translation techniques applied in dealing with

micro-translation units. The application of

translation techniques was conducted by

comparing the micro units of SL text and TL text.

Furthermore, Molina and Albir (2002) suggest

that translation techniques refer to “actual steps

taken by the translators in each textual unit”.

Thus, translation techniques can be interpreted as

the functional steps chosen in analyzing the

translation units, which further becomes the basis

for diverting SL messages into TL on a micro

level that includes words, phrases, clauses, or

sentences. Molina and Albir (2002) describe a

number of translation techniques: literal,

borrowing, generalization, particularization,

amplification, reduction, common equivalent,

linguistic amplification, linguistic compression,

transposition, modulation, description, adaptation,

compensation, substitution, discursive creation,

and variation techniques.

The table above shows that the UMT’s

translation used only two translation techniques

oriented to the SL, namely literal technique and

borrowing technique. Overall, the UMT’s

translation used the SL-oriented translation

techniques up to 154 times (38.2%). The use of

translation techniques that are oriented to the SL

with relatively significant frequency shows that

the translations of the iltifat verses in the UMT’s

translation relatively have equivalence to the

source text.

Interestingly, of the 16 borrowing techniques,

there are 13 naturalized borrowing techniques, in

which the borrowed words have been adjusted to

the phonotactic and morphotactic rules applicable

in Indonesian language. The remainder is three

pure borrowing techniques where the words are

borrowed in the translation have not been adjusted

to the applicable phonotactic and morphotactic

rules. For example, the word Masjidil Haram is

contained in the translation of Chapter Al-Isra’

[17] verse 1 should be written Masjidilharam (see

KBBI, 2016). The reason is that the word is a

bound form and is therefore written into a word,

Masjidilharam, not the Masjidil Haram.

From the table above it also appears that the

UMT’s translation mostly uses the TL-oriented

translation techniques, especially transposition

technique (64 times), amplification (54 times),

linguistic amplification (48 times), reduction (47

times), modulation (22 times), generalization (10

times), and particularization (4 times). Overall,

there are 249 the TL-oriented translation

techniques. This amounts to 61.8% of all

translation techniques used by the UMT’s

translation in translating the iltifat verses. The

number of the TL-oriented translation techniques

indicates that the UMT’s translation has a strong

domestication tendency in translating the iltifat

verses. Ni (n.d.) explains that the tendency of

domestication is related to the target-culture-oriented

translation. In practice, unusual expressions to the

target culture are usually turned into some familiar

ones in TL so that the translated text become easier

for target readers. This finding confirms that the

UMT’s translation, according to its name Al-

Qur’anul Karim Tarjamah Tafsiriyah, has an

interpretive tendency to translate the iltifat verses.

This tendency is characterized by the number of

additional linguistic elements in the TL, which are

not actual, in the SL as the realization of linguistic

amplification technique (48 times). In addition,

the use of transposition technique (64 times)

shows the number of shifts in TL, at the terms of

structure, category, and level.

In practice, the use of the TL-oriented

translation techniques such as transposition,

amplification, linguistic amplification, and

reduction can improve the acceptability of the

iltifat verses translations. The use of transposition

technique is done by making a shift in the terms

of category, level, or structure. The amplification

technique is performed by generating or

explicating linguistic elements implicitly

contained in the SL. The linguistic amplification

technique is performed by presenting additional

linguistic elements that are not actually contained

in the SL. The reduction technique is performed

by dissolving one or more linguistic elements

within TL (see Molina and Albir, 2002).

The abundance of transposition techniques

confirms that Arabic and Indonesian are different

in both language and culture, especially since the

two languages come from different language

families (Al Farisi, 2015). In addition to the depth

of the Qur’anic vocabulary meaning, Al-Ghazalli

(2012) reports that grammatical inequality often

leads to redundancy in the translation of Qur’anic

verses. To avoid the redundancy of translation,

The Translation of Iltifat Verses: An Analysis of Translation Ideology

263

the adjustment in the iltifat verses translation

becomes necessary. Therefore, the use of

transposition technique often becomes inevitable

in translation. In practice, the structural

differences between Arabic and Indonesian

necessitate a shift in grammatical categories and

syntactic functions. The use of transposition

technique is necessary, among others, to present

readers easy-to-understand translations (see

Molina and Albir, 2002). The transposition

technique is also required to avoid the

interference of the Arabic structure against

Indonesian.

According to Haleem (1992), there are

approximately 60 styles in the Qur’an containing

the transition from the third person deixis to the

second person deixis. This number may differ

from one expert to another. For example, there are

cross-references in the translation of the verse

illustrated in Chapter ‘Abasa [80] verses 1-3. In

these verses, according to the majority of

translators, there is a shift from the single third

person deixis (him) to the single second person

deixis (you) as follows.

It is known that in those verses cited above

there are verb (literal: he frowned) and

(literal: he turned) containing the person deixis

(he). The person deixis he then undergoes a shift

to the person deixis (you) as contained in the

phrase (literal: what makes you know).

The research findings show that the UMT’s

translation consider the Chapter ‘Abasa [80],

verses 1-3, in the iltifat stylistic corridor as shown

in the following translation.

Muhammad bermuka masam dan memalingkan

wajahnya, ketika ada seorang laki-laki buta

datang untuk menemuinya. Wahai Muhammad,

apakah engkau tahu maksud kedatangan laki-

laki buta itu? Barangkali dia datang dengan

hati bersih.

(Literal: Muhammad frowned and turned his

face, when a blind man came to meet him. O

Muhammad, do you know the purpose of the

coming of the blind man? Perhaps he came

with a clean heart.)

This means the person deixis contained in the

verbs and and the person deixis you

contained in the phrase refers to the same

person, the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). In the

UMT’s translation, the verb is translated by

using couplet procedure that combines

transposition and literal techniques.

The existence of linguistic element

Muhammad is the realization of transposition

technique, which leads to the shift of person

deixis (he) in the SL into the linguistic element

Muhammad in the TL, and the linguistic element

bermuka masam (frowned) is the realization of

literal technique in translating verb. The

existence of the linguistic element Muhammad in

translation is seen to facilitate the reader in

understanding the translation of the verse, because

the reader does not have to search for the

antecedent of the person deixis (he) contained

in the verb .

In the next verse, the phrase contains

person deixis (you) which syntactically serves

as maf’ul bih (object). However, the syntactic

function as object undergoes a shift into fa’il

(subject) in the TL. In this case, the shifting of the

structure occurs because of the use of

transposition technique in translating the phrase.

Translation readability is also reinforced by the

presence of additional linguistic element maksud

kedatangan laki-laki buta itu (the purpose of the

coming of the blind man), although the existence

of this linguistic element, as already mentioned in

the previous verse translations, causes the

translated text to be redundant. This additional

linguistic element is present in the translation as

the realization of linguistic amplification

technique.

4 CONCLUSION

Theoretically, the translation of the iltifat style

can be categorized as risky because the existence

of two persons deixis in one (series of) verse(s)

refers to a same entity. The use of literal

technique has a potential to cause

misunderstandings among readers. The UMT’s

translation has precisely been correct to translate

the elements of person deixis in these verses by

using the amplification and transposition

techniques. Handling the person deixis by using

the transposition technique creates a shifting in

function and category of syntax in translation.

Shifting of function and category of syntax is seen

to facilitate readers to understand the translation

of iltifat verses.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

264

REFERENCES

Al-Akhdhari, A. 2013. Syarhu Jauharil Maknuni fil

Ma’ani wal Bayani wal Badi’. Beirut: Daru Ihyail

Kutubil ‘Arabiyyah.

Al-Atsir, I. (n.d.). Al-Mutsuluts Tsair fi Adabil Katibi

wasy Sya’ir. [Online]. Tersedia:

http://www.alwaraq.com [10 July 2017].

Al-Badani, N.A., Awal, N.M. and Zainudin, I.S. 2015a.

“The Implicature of Glorification in the Translation

of Reference Switching (Iltifat) from Third to First

Person Pronoun in Surat Al-Baqarah”. Australian

Journal of Sustainable Business and Society, vol. 1

(2), pp. 54-63.

Al-Badani, N.A., Awal, N.M. and Zainudin, I.S. 2015b.

“Translation of Reference Switching (Iltifat) in

Surah Al-Baqarah”. Journal of Social Sciences and

Humianities, special issue 2, pp. 140-148.

Al-Badani, N.A., Awal, N.M., Zainudin, I.S., and

Aladdin, A. 2014. “Translation Strategies for

Reference Switching (Iltifat) in Surah Al-Baqarah”.

Asian Social Science, vol. 10 (16), pp. 176-187.

Al Farisi, M.Z. 2017a. “Ketedasan Terjemahan Ayat-

ayat Imperatif Bernuansa Budaya”. El-Harakah:

Jurnal Budaya Islam, 19 (2), pp. 159-176.

Al Farisi, M.Z. 2017b. “Analisis Pragmatik Wacana

Terjemahan Berdampak Hukum”. Asy-Syir’ah:

Jurnal Ilmu Syari’ah dan Hukum, 19 (2), pp. 159-

176.

Al Farisi, M.Z. 2015. “Speech Act of Iltifat and its

Indonesian Translation Problem”. Indonesian

Journal of Applied Linguistics (IJAL), 4 (2), pp.

214-225.

Al-Ghazalli, M.F. 2012. “A Study of the English

Translations of the Qur’anic Verb Phrase: the

Derivatives of the Triliteral”. Theory and Practice

in Language Studies, 2, pp. 605-612.

Eggins, S. 2004. An Introduction to Systemic

Functional Linguistics (2

nd

ed.). London:

Continuum.

Esfandiari, M.R. and Jamshid, M. 2012. “Relevance,

Processing Effort, and Contextual Effect in Farsi

Translation of Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a

Young Man”. Studies in Literature and Language, 3

(3), pp. 86-91.

Haleem, Abdel M.A.S. 1992. “Grammatical shift for

rhetorical purposes: iltifat and related features in the

Qur’an”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and Africal

Studies, vol. 55, part 3, pp. 407-432.

Hidayat, D. 2009. Al-Balaghatu lil Jami’ wasy

Syawahidi min Kalamil Badi’. Semarang: PT.

Karya Toha Putra.

Huang, Y. 2014. Pragmatics (Second Edition). Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Hubal, M. 2015. Balaghatu Uslubil Iltifat fil Qur’anil

Karim wa Asraruh. Unpublished Master’s Thesis.

University of Kasdi Merbah.

KBBI. 2016. KBBI Daring Edisi Kelima. [Online].

Tersedia: https://kbbi.kemdikbud.go. id/Beranda

[15 June 2017].

Larson, M.L. 1984. Meaning-Based Translation: A

Guide to Cross-Language Equivalence. Boston:

University Press of America.

Mirdehghan, M., Zahedi, K. and Nasiri, F. 2012.

“Iltifat, Grammatical Person Shift and Cohesion in

the Holy Quran”. Global Journal of Human Social

Science, vol. 12 (2), pp. 1-8.

Molina, L. and Albir, A.H. 2002. “Translation

Techniques Revisited: A Dynamic and

Functionalist Approach”. Meta, 47 (4), pp. 498-

512.

Ni, Z. (n.d.). Domestication and Foreignization. [Online].

Tersedia di: http:// www.188mb .com

/Newinfor/html/3584.htm. [14 May 2017].

Osimo, B. 2013. On-Line Translation Course. [Online].

Tersedia: http://www.logos. it /pls/

dictionary/linguistic_resources.cap_1_1_en?lang=en

[05 January 2017].

Thalib, Muhammad. 2017. Al-Qur’anul Karim

Tarjamah Tafsiriyah. Solo: Qolam Mas.

The Translation of Iltifat Verses: An Analysis of Translation Ideology

265