Syntactic Awareness of Early Childhood Aged 5-6: A Case of

Sentence Structure

Maghfira Zhafirni, Wawan Gunawan and Eri Kurniawan

Department of English Education, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia

eri_kurniawan@upi.edu

Keywords: Syntactic Awareness, Active Sentence, Passive Sentence, Kindergarten Students, Flash Card.

Abstract: This study seeks to examine syntactic awareness in early childhood aged 5-6 by using word-order correction

task. The students were tested through two media; picture and flash card. The data used in the present study

were gathered from two kindergartens that consist of forty-five students in Bandung; Kindergarten A was

about 21 students and Kindergarten B was about 24 students. This study employs a quantitative approach and

was collected in two ways: 1) visual tasks that consist of identification and correction task, and 2) observation

during the execution by using recorders. The finding shows that syntactic awareness has emerged among

kindergarten students. However, since the task consists of active and passive sentence tasks, the finding shows

different results. In Kindergarten A, results in active sentence task are 78.9% students can identify wrong

sentences, and 78.17% students can correct the jumbled sentence. In passive sentence task, 80.9% students

can identify wrong sentences, and 55.9% students can correct the jumbled sentence. Meanwhile, in

Kindergarten B, results in active sentence task are 92,1% students can identify wrong sentences, and 57.9%

students can correct the jumbled sentence. In passive sentence task, 95.8% students can identify wrong

sentences, and 35.9% students can correct the jumbled sentence. Then, the total number of students that can

answer the test is 73.6% for Kindergarten A and 71.3% for Kindergarten B. Some of the students can identify

which sentence is wrong, but they confuse how to put the words into the right order. Those findings reveal

that: 1) Kindergarten A excels in syntactic awareness, but the score’s difference is not significant, that is only

2.3%, 2) Correction task is more difficult than identification task, and 3) Passive sentence is more difficult

than active sentence.

1 INTRODUCTION

The period in which children start to enter their first

formal school (kindergarten) is interesting to be

investigated. Kindergarten is expected to help

students develop potentials, such as language skill

(Nova, 2012). Language skill will help the children to

understand the words, sentences, and also the

relationship between spoken language and writing

(Karmila, 2012). Furthermore, language skill also

enables children to engage with other people and

learn from their surroundings and in the classroom.

By age five, children essentially master the sound

system and grammar of their language and acquire

thousands of words (Hoff, 2009). Hoff (2009) also

mentions that when children gradually master the

grammar of a language, they become able to produce

increasingly long and grammatically complete

utterances. It is because age five is a period of time

which a high-level of achievement is reached (Golden

Age).

According to Robertson (2017), the first five

years of children’s lives are the most important in

terms of Language Development. Therefore, it is

important for them to acquire reading or writing skill.

Among other areas of metalinguistic development,

syntactic awareness is relevant to the acquisition of

reading. Syntactic awareness refers to the child’s

ability to notice the internal grammatical structure of

sentences (Genc, 2013). Tunmer and Hoover (1992)

mentioned that syntactic awareness has been

facilitating reading development via a more direct

contribution to reading comprehension. However,

before children learn to read, they need to develop the

ability to speak, listen, and understand. Tasks that

measure syntactic awareness focus on the sentence

level and require the language used to reflect on and

Zhafirni, M., Gunawan, W. and Kurniawan, E.

Syntactic Awareness of Early Childhood Aged 5-6: A Case of Sentence Structure.

DOI: 10.5220/0007165102330238

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 233-238

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

233

manipulate the grammatical well-formedness and

syntactic structure of sentences (Bowey, 1986; Nagy

& Scott, 2000).

A number of studies regarding syntactic

awareness have been conducted in some fields. For

instance, in 2010, Davidson, Rasche, and Pervez

investigated 3–5 years old bilingual children. The

result shows that bilingual children aged 3 and 4 were

better at detecting grammatically incorrect sentences

than their monolingual peers. However, no significant

differences appeared in monolingual and bilingual

children’s ability to detect grammatically correct

sentences. Then, in Apel and Brimo (2015) were

examining the direct and indirect effects of syntactic

knowledge in a model of reading comprehension

among 9th and 10th-grade students. It shows that

syntactic awareness did not contribute significant

variance and they did not find an indirect effect of

syntactic awareness through syntactic knowledge on

reading comprehension.

Meanwhile, studies related to language

awareness, specifically on syntactic awareness of

Indonesian children is relatively small (Komara,

2016). In 2012, Impuni measured syntactic awareness

to children aged 5 by retelling the story. The result

shows that the children produced different complex

and compound sentences. Meanwhile, Komara

(2016) focused on assessing preschool students’

syntactic awareness through their ability to correct

and identify the sentences in the level of verbal

structures by using audiovisual. He found that even

though the children could produce or manipulate S-P-

O (SVO), some of them could not answer the same

sentence on jumbled ways.

The present study will examine the student in

active and passive sentence structure by using word

order and it will be tested through a flash card.

According to Tunmer (1987) in Nation and Snowling

(2000), syntactic awareness had been measured using

word order correction tasks in which the children get

a challenge to the scrambled sentence. Using word

order is beneficial for the student because it will train

their mental capacity and developmental abilities to

understand the logic and reasoning behind learning

the parts of the sentence (Young, 2017). Nation and

Snowling (2000) mention that for children, passive

sentences are harder than active sentences.

Meanwhile, in Indonesia, Dardjowidjojo (2005)

mentions that passive form in Bahasa Indonesia is

more dominant rather than active form so that

children are often heard passive form than active

form. Hence, Indonesian children able to produce

passive form much earlier rather than active form.

2 LITERARY REVIEW

2.1 Metalinguistic Awareness

Metalinguistic awareness has been defined as “the

ability to reflect upon and manipulate the structural

features of spoken language itself as an object of

thought.” (Tunmer & Herriman, 1984 as cited in

Hodson & Aikins, 2004). Metalinguistic awareness is

high level linguistic skills which requires three

aspects which are an ability to comprehend and

produce language in a communicative way, an ability

to separate language structure from communicative

intent, and an ability to use control processing to

perform mental operations on structural features of

language (Chaney, 1991 as cited in Genc, 2013).

Metalinguistic awareness covers morphological

awareness, syntactic awareness and phonological

awareness. Tunmer (1984) explains in detail that

metalinguistic is such a higher level of using

language. Its definition lies in language that describes

phoneme, morpheme, and syntax.

2.2 Syntactic Awareness

Syntactic awareness refers to the child’s ability to

notice internal grammatical structure of sentences

(Genc, 2013). It measures children to identify correct

and incorrect grammatical constructions (the

grammaticality judgment task). Although children are

unable to say a relevant rule structure, they may be

aware of the language systematicity. Syntactic

awareness may be the most promising candidate as an

additional measure of metalinguistic awareness and

that more research on this measure is needed

(McGuinness, 2005; Roth et al., 1996). Tunmer

(1987) adds that syntactic awareness will give the

child’s ability to reflect upon and to manipulate

aspects of the internal grammatical structure

sentences.

Syntactic awareness is a part of metalinguistic

skills. Cain (2007) mentions that because it concerns

with the ability to consider the structure rather than

the meaning sentence, it can aid students’ ability to

detect and correct word recognition errors. Moreover,

Bowey (1987) mentions that syntactic awareness may

be enhance their comprehension monitoring abilities.

According to Brimo and Apel (2017) syntactic

awareness is measured by conducting two tasks: (a) a

grammatical correction task, which required students

to correct an orally-presented sentence that contained

errors on subject-verb agreement and (b) a word-

order correction task, which required students to

rearrange words to create a grammatically correct

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

234

sentence. The parameters of syntactic awareness are

assessed through two paradigms (Davidson et al.,

2010) which are identification and correction. An

identification paradigm is used to identify a correct

grammar while a correction paradigm is used by

correcting ungrammatical sentences .

2.3 Syntactic structures in Bahasa

Indonesia

Syntax is a branch of linguistic that addresses the

internal structure of sentence (Manaf, 2009). Aprilia

(2014) also adds that syntax is also called sentence

science that describes the relationship between

elements of language to form a sentence. It focuses

on the discussion of phrases, clauses, sentences as

systemic unity. In this study, a phrase is the smallest

unit meanwhile sentence is the largest unit. Syntax

needs to be studied because it learns the sentence

form which is the smallest complete language unit.

Syntax relates to other language elements that are

related to the constituent elements, such as phoneme,

word, and so on.

English language has become a much studied by

students. However, the structure in English is

different with Bahasa Indonesia. First, the syntactic

pattern in Bahasa Indonesia generally consists of

subject (S), predicate (P), object (O), and adverb (K).

Second, Putrayasa (2015) mentions that Bahasa

Indonesia is still use a root-base language. He also

adds that it does not have any gender. As for example,

‘Dia suka membaca buku’ . The word dia doesn’t

refer to any man or woman. Meanwhile in English, it

is clear that it must be ‘he/she likes to read a book’.

Third, there are no articles in Bahasa Indonesia (a, an,

or the), however in Bahasa Indonesia the prefix se-

can act in similar manner such as sebuah or a piece.

In Bahasa Indonesia, the article can be skipped

because the role is not important. Fourth, Bahasa

Indonesia does not have a plural concept, to express

the concept of something being ‘more than one’. As

for example, in English ‘I have three apples’,

meanwhile in Bahasa Indonesia ‘saya mempunyai

tiga apel’.

2.4 Children’s Language Development

Genishi (2011) mentions that children in 12 months

developing many foundations that underpin speech

and language development. Then, in the third year

and so on children will understand more than they

say. Language development supports children’s

ability to communicate, to understand feeling, to

support thinking and problem solving. The

understanding of language is the critical step in

literacy, and it is the basis for learning to read and

write (Casanave, 1994). Language develops with

physical growth and cognitive development (Piaget,

2008). Its development is more complex to be

understood.

According to Piaget and Vygotsky, children’s

language development consists of eight stages (Piaget

& Vygotsky, as cited in Tarigan, 2011, p.41). The

first stage is babbling (prelinguistic, aged 0.0 – 0.5).

In this stage, babies have been given the feeling to

have social interaction and language. The second

stage is “nonsense word” which happens when babies

reach the age of 0.5 – 1.0. In this stage, babies start to

babble which is more language-like but is still not

clear. This stage occurs specifically in 6-9 months of

age. The third stage is one-word sentence which

specifically occurs in 18-20 months of age. In this

stage, babies can express anything without limited

words. The fourth is two-word sentence’s stage,

specifically at the age of 2-3. This stage is called

telegraphic speech where the children use

nominalism, adverb or adjective. The fifth is grammar

development stage which specifically occurs at the

age of 3-4. This stage is where the children start to

improve their grammar. The sixth stage is pre-adult

grammar, which specifically occurs at the age of 4-5.

This stage shows that children start to produce

complex sentence. The last stage is full competence

stage, which occurs specifically at the age of 5-7. In

this stage, children acquire language like adult

although it is limited in a number of vocabularies.

3 METHODOLOGY

This study employs Quantitative method. As

Cresswell (2014) mentions that quantitative method

contains numeric descriptions or opinions of

population by studying that population. This method

is to test the impact of the treatment on an outcome.

Babbie (2010) adds that quantitative method also

emphasizes objective measurement and numerical

analysis of data using computational techniques. The

data of the study is processed by using excel 2010.

The data was collected from two Kindergarten

that consists of forty-five students; kindergarten A

was about 21 students, and kindergarten B was about

24 students. They were chosen because the

requirement of the researcher to find out syntactic

awareness in early childhood. These students were

five and six years old, and most of them could read

and others could not. The data was collected using

instrument to meet the purpose of the study. In this

Syntactic Awareness of Early Childhood Aged 5-6: A Case of Sentence Structure

235

study, there were two ways of collecting the data:

syntactic awareness task and observation 3-4 hours a

day by recording the children’s performance during

the execution of task. The task of syntactic awareness

was in the form of instrument to identify and correct

jumbled sentences.

There were two stages of collecting the data. First,

the tasks were tested to know whether they work out,

had the mistakes, or need revision. After deciding the

best tasks, children were tested in the class. Second,

the execution of the tasks was recorded with Android

for observing children’s syntactic performance. The

recorded data shows all the responses and production.

In detail, children came to the class in turn and

individually. The teacher gave the writer a room for

the test, and let the writer did the test during school’s

activity and the test were lasted for about a month.

Before testing the children, the writer broke the ice by

asking what games they like, how old they were, and

then following their conversation. In the task,

children were first asked to tell what the images in the

picture were. It is the stimulus that would raise the

children’s knowledge of the characters in the pictures.

Second, the children were asked what the characters

do in the pictures. This question was used to validate

whether the children really know what the characters

were doing in the pictures. Then, the writer gave the

flashcard that consists of a jumbled sentence. After

that, the writer read the jumbled sentence and asked

whether it sounded ‘enak’ (good) or ‘gak enak’ (not

good). When the children said ‘enak’, the writer gave

the next picture and sentence. However, when the

student said ‘gak enak’ (not good), the writer asked

the student to correct the sentence through flashcards

that have been given.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

This section describes the findings of the assessment

test of syntactic awareness in Bahasa Indonesia. This

study consists of two section tasks, the first was

assess active sentence and the second was assess

passive sentence. Both of active and passive

sentences contain two assessments respectively;

identification and correction.

The total number of forty-five students who took

the test was 76, 9% students answered active

sentences correctly. Meanwhile, in passive sentences

the students answered 67, 8% sentences correctly.

Dardjowodjojo (2005) mentions that in Bahasa

Indonesia, passive sentence patterns are often used

instead of active sentence patterns. Hence, children

are more dominant using passive sentences than

active sentences. However, the findings show

different. Based on the test’s result, students are more

familiar with active sentence rather than passive

sentence.

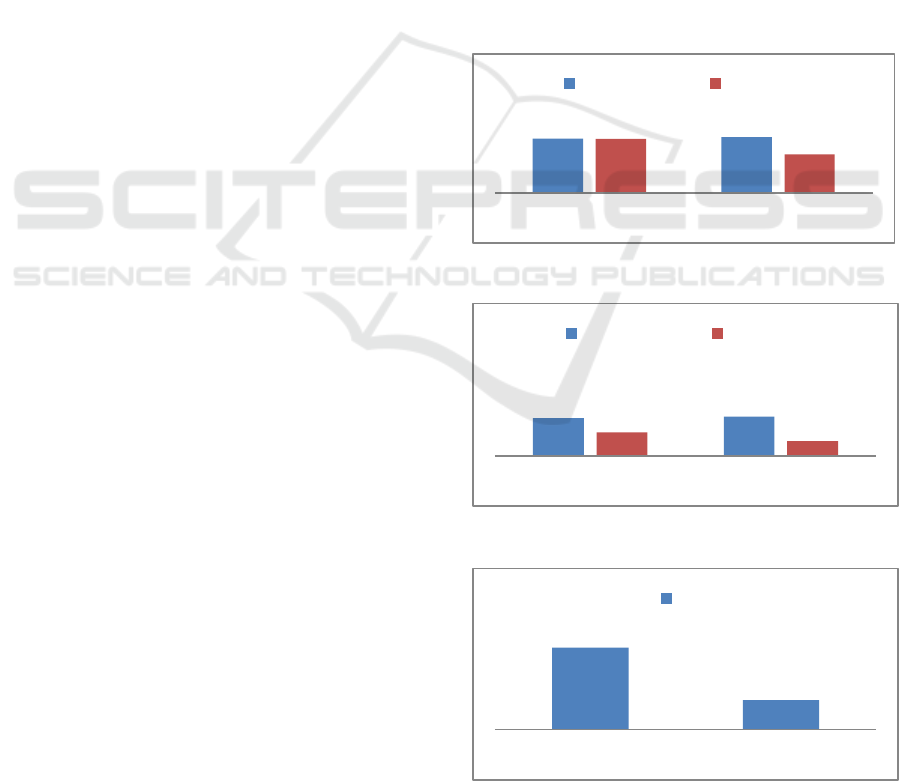

In Kindergarten A, results in active sentence task

are 78, 9% students can identify wrong sentences, and

78, 1% students can correct the jumbled sentence. In

passive sentence task, 80, 9% students can identify

wrong sentences, and 55, 9% students can correct the

jumbled sentence. Meanwhile, in Kindergarten B,

results in active sentence task are 92,1% students can

identify wrong sentences, and 57,9% students can

correct the jumbled sentence. In passive sentence

task, 95, 8% students can identify wrong sentences,

and 35, 9% students can correct the jumbled sentence.

Then, the total number of students that can answer the

test is 73, 6% for Kindergarten A and 71,3% for

Kindergarten B. Some of the students can identify

which sentence is wrong, but they confuse how to put

the words into the right order.

Figure 1: Kindergarten A.

Figure 2: Kindergarten B.

Figure 3: Total Percentage of two Kindergartens.

78.90%

80.90%

78.10%

55.90%

Active Sentence Passive Sentence

Identification Correction

92.10%

95.80%

57.90%

35.90%

Active Sentence Passive Sentence

Identification Correction

73.60%

71.30%

Kindergarten A Kindergarten B

Total

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

236

5 CONCLUSION

As explained previously, this study assesses students’

syntactic awareness in Bahasa Indonesia. The

quantitative data were analysed by using MS. Excel

2010. According to the result, it can be concluded that

children ages 5-6 years have had a high syntactic

awareness. It can be seen from the test results that

children are able to answer more than 50% of the

answers correctly. The finding is similar with Nation

and Snowling (2000), that children are able to answer

active sentence rather than passive sentence. In other

way, the students were had difficulties in correcting

jumbled sentence, specifically on passive sentence.

REFERENCES

Aprilia, N. K. 2014. Penggunaan Kalimat Bahasa

Indonesia dalam Penulisan Teks Berita Peserta

Ekstrakulikuler Jurnalistik SMAN 01Ponggok Tahun

Pelajaran 2013/2014 (Unpublished master thesis).

Universitas Malang, Malang.

Bowey, J. A., Patel, R. K. 1988. Metalinguistic ability and

early reading achievement. Applied

Psycholinguistics, 9(4), 367-383.

Brimo, D., Apel, K., & Fountain, T. 2015. Examining the

contributions of syntactic awareness and syntactic

knowledge to reading comprehension. Journal of

Research in Reading.

Brimo, D., Apel, K., & Fountain, T. 2015. Examining the

contributions of syntactic awareness and syntactic

knowledge to reading comprehension. Journal of

Research in Reading, 40(1), 57-74.

Cain, K. 2007. Syntactic awareness and reading ability: Is

there any evidence for a special relationship?. Applied

psycholinguistics, 28(04), 679-694.

Casanave, C. P. 1994. Language development in students'

journals. Journal of Second Language Writing, 3(3),

179-201.

Creswell, J. W. 2009. Research design pendeketan

kualitatif, kuantitatif, dan mixed edisi ketiga (Fawaid,

A., Trans.). Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar.

Dardjojo, Soenjono. 2005. Psikolinguistik: pengantar

pemahaman Bahasa manusia edisi kedua, Jakarta:

yayasan obor Indonesia.

Davidson, D., Raschke, V. R., Pervez, J. 2010. Syntactic

awareness in young monolingual and bilingual (Urdu–

English) children. Cognitive Development, 25(2), 166-

182.

Genç, H. 2013. A comparative study: Syntactic awareness

in young Turkish monolingual and Turkish-

english0bilingual children.

Glass, G. V., Hopkins, K. D. 1984. Inferences about the

difference between means. In Statistical Methods in

Education and Psychology (pp. 230-232). Prentice-

Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Gleitman, L. R., Gleitman, H., Shipley, E. F. 1972. The

emergence of the child as grammarian. Cognition, 1(2),

137-164.

Hoff, E. 2009. Language development at an early age:

Learning mechanisms and outcomes from birth to five

years. Language development and literacy, 7.

Impuni, I. 2012. Pemerolehan Sintaksis Anak Usia Lima

Tahun Melalui Penceritaan Kembali Dongen

Nusantara. Jurnal Penelitian Humaniora, 13(1), 30-41.

Karmila. 2012. Peningkatan kemampuan baca anak usia

dini melalui permainan rolet kata di taman kanak-kanak

aisyiyah kubang agam. Jurnal Pesona PAUD, 1(03).

Komara, Teja. 2016. Syntactic Awareness of Indonesian

Preschool Students (Unpublshied master thesis).

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia.

Lans, W., and van der Voord, T., 2002 Descriptive research.

In Jong, T. M. and van der Voordt, D.J.M. Ways to

study architectural, urban and technical design. Delft:

DUP Science, pp. 53-60.

Manaf, N. A. 2009. Sintaksis: Teori dan Terapannya dalam

Bahasa Indonesia.

Manaf, Ngusman Abdul. 2009. Sintaksis: Teori dan

Terapannya dalam Bahasa Indonesia. Padang:

Sukabina Press

Martohardjono, G., Otheguy, R., Gabriele, A., de Goeas-

Malone, M., Szupica-Pyrzanowski, M., Troseth, E., ...

& Schutzman, Z. 2005. The role of syntax in reading

comprehension: A study of bilingual readers.

In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on

Bilingualism (pp. 1522-1544). Somerville, MA:

Cascadilla Press.

McCusker, K. and Gunaydin, S. 2014. Research using

qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods and choice

based on the research. Perfusion, pp.1-6.

Mokhtari, K., & Thompson, H. B. 2006. How problems of

reading fluency and comprehension are related to

difficulties in syntactic awareness skills among fifth

graders. Literacy Research and Instruction, 46(1), 73-

94.

Nagy, W. E., Anderson, R. C. 1995. Metalinguistic

awareness and literacy acquisition in different

languages. Center for the Study of Reading Technical

Report; no. 618.

Nation, K., Snowling, M. J. 2000. Factors influencing

syntactic awareness skills in normal readers and poor

comprehenders. Applied psycholinguistics, 21(02),

229-241.

Nordquist, Richard. 2016, July 31. Grammaticality (well-

formedness). Retrieved from

https://www.thoughtco.com/g00/grammaticality-well-

formedness-

1690912?i10c.referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.googl

e.co.id%2F

Nova, W. S. O. 2012. Peningkatan kemampuan baca anak

usia dini permainan bowling kata di pendidikan anak

usia dini agam. Jurnal Pesona PAUD, 1(02)

Otto, Beverly. 2005. Perkembangan Bahasa pada anak usia

dini Edisi ketiga, Jakarta:Kencana

Piaget. 2008. The language and thought of the child (Third

ed.). London: Routledge

Syntactic Awareness of Early Childhood Aged 5-6: A Case of Sentence Structure

237

Putrayasa, I. B. 2015. Pembelajaran menulis paragraph

deskripsi berbasis mind mapping pada siswa kelas VII

SMP Laboratorium Undiksha. JPI (Jurnal Pendidikan

Indonesia), 4(2).

Robertson, Saly. January, 11

2017. Language development

in children. News Medical Life Sciences. Retrieved

from https://www.news-medical.net/health/Language-

Development-in-Children.aspx

Roger Brown and Ursula Bellugi. 1964. Three Processes in

the Child's Acquisition of Syntax. Harvard Educational

Review: July 1964, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 133-151.

Tarigan, H. G. 2011. Pengajaran pemerolehan bahasa.

Bandung: Angkasa

Tong, X., Deacon, S. H., Cain, K. 2014. Morphological and

syntactic awareness in poor comprehenders: Another

piece of the puzzle. Journal of Learning

Disabilities, 47(1), 22-33.

Tunmer, W. E., Nesdale, A. R., Wright, A. D. 1987.

Syntactic awareness and reading acquisition. British

Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5(1), 25-34.

Unicef. 2014. Early Childhood Development: The key to a

full and productive life.

Unmer, W.E and Hoover, W.A. 1992. Cognitive and

linguistic factors in learning to read. In P.B. Gough,

L.C. Ehri and R. Treiman (Eds.), Reading Acquisition.

Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum.

Young, Collin. 2017, January 30

th

. Why is word order

important?. Retrieved from http://www.instituto-

exclusivo.com/blog/why-word-order-important

Zhang, B. 2003. On 'gazing about with a checklist' as a

method of classroom observation in the field experience

supervision of pre-service teachers: A case study.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

238