Father as a Caregiver: The Thipology of Father Parenting Style

While Mother doesn’t Exist and the Effect to Child Autonomy

Corry Caromawati

1

, and Agung Kurnia

2

1

Institut Teknologi Nasional, Bandung, Indonesia

2

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia

{Corrycaromawati, agungkurnia.aku}@gmail.com

Keywords: English as a lingua franca, intelligibility, vowel contrast.

Abstract: This study investigated the characteristics (place and duration) of the vowel contrasts produced by Indonesian

students of English and whether they contrasted the lax and tense vowels. Ten female students participated in

this study. The data were collected through a listening and speaking task focusing on the vowel contrasts and

analyzed using acoustic analysis. The findings showed that the participating students produced the /u/ and

/ʊ/ at the relatively expected locations and contrasted them, but not the other vowel contrasts (/ɛ/ and /æ/ and

/i/ and /ɪ/). In terms of duration, the vowels produced by the participants were inconsistent, and they were not

contrasted. These findings are interpreted as a support to the previous study, and advocate for more

pronunciation instruction through listening exercise to expose the difference of the lax and tense vowels.

1 INTRODUCTION

The main aim of learning a language is to be able to

communicate with people who speak that particular

language. In order to achieve the aim, Jenkins (2000)

suggests that language learners should be able to be

intelligible when speaking to the native speakers or

other speakers of that language. Therefore, it is

important for language learners to avoid errors in

producing segmental (individual sounds) and

suprasegmental features such as pitch and rhythm that

will cause communication breakdowns. Even though

both segmental and suprasegmental units are

important, Jenkins’ (2000) study showed that errors

in segmental units tend to be more problematic than

suprasegmental, especially when the errors occur

frequently due to the speakers’ inability to produce

the proper ones. Nonetheless, not all errors in

segmental units will cause communication

breakdowns. There are some segmental units that are

more problematic than others. These units are

considered to have higher functional load because

when a speaker does not produce them correctly, a

communication misunderstanding or breakdown will

be inevitable. Therefore, it is necessary for language

speakers to be aware of this risk and learn how to be

able to produce them correctly.

Even though Jenkins (2000) claimed that vowel

quality does not affect intelligibility, a study

conducted by Deterding and Mohamad (2016)

provides evidence that vowel quality was involved in

a substantial number of communication breakdown

occurrences found in the Asian Corpus of English

(ACE), one occurrence became a strong support of

how vowel quality became the main factor of a

communication breakdown.

It is believed that language learners will find the

segmental unit production challenging if the features

either do not exist or are different to those of their

mother tongue. For Indonesian speakers of English,

vowel production can be problematic since the vowel

system in Indonesian language is not similar to that of

English because English has lax and tense vowel

pairs. These vowel pairs indeed have high functional

loads (Brown, 1991), especially when the vowels are

in taboo words. For example, the minimal pairs beach

[bitʃ] and bitch [bɪtʃ]

Koffi (2016) also believed that if the vowel pairs

are not contrasted by at least 61 Hertz, the listeners

will not be able to perceive them well. Unfortunately,

Indonesian speakers of English who lived in the USA

only contrasted the dimension of the /u/ and /ʊ/

(Caromawati & Muhammad, 2015). As to our

knowledge no studies have been done on vowel

contrasts of Indonesian learners of English learning

58

Caromawati, C. and Kurnia, A.

Father as a Caregiver: The Thipology of Father Parenting Style While Mother doesn’t Exist and the Effect to Child Autonomy.

DOI: 10.5220/0007162000580062

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 58-62

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

the language in higher education, we were interested

in investigating their production.

Based on the aforementioned motivation, this

study sought answers to these following research

questions:

1. What are the characteristics of vowel contrasts

/ɛ//æ/, /u//ʊ/, and /i//ɪ/ of Indonesian learners of

English regarding their place of articulation and

duration?

2. Do Indonesian learners of English contrast the

lax and tense vowels?

2 METHODS

2.1 Data Collection

There were ten female learners of English from a

private university in Indonesia participated in this

study. There were no particular reasons for choosing

female students. However, it is strongly believed that

two genders have different pronunciation

characteristics. Peterson and Barney (1952)

mentioned that due to the difference in size of men

and women, women have higher resonance

frequencies than men. This fact became our

consideration to include one gender only. These

participants had very low score on a paper-based

TOEFL-like, under 425 and had never been to an

English speaking country. However, when the study

was conducted, they were studying English in a

private university in Bandung, and we assumed that

they were exposed to English language outside the

classroom, such as through movies, songs, etc.

These participants were asked to listen to audio

files of an American English speaker saying a

carrying phrase “Now I say …” followed by a token

containing the target vowels /ɛ//æ/, /u//ʊ/, and /i//ɪ/

with one consonant before and after them, which is

referred to what we call a frame. In this study, we

used four CVC frames, F_L, H_D, P_L, and P_T.

These frames were acknowledged by the participants

who were asked to focus only on the vowels. Before

they recorded their voice, the learners were allowed

to listen to the audio as many times as they needed

until they were confident with what they heard from

the recording, and then repeated it. In total, each

participants produced 24 tokens. Therefore, there

were 240 tokens recorded using Audacity and

analyzed to answer the two research questions in this

study.

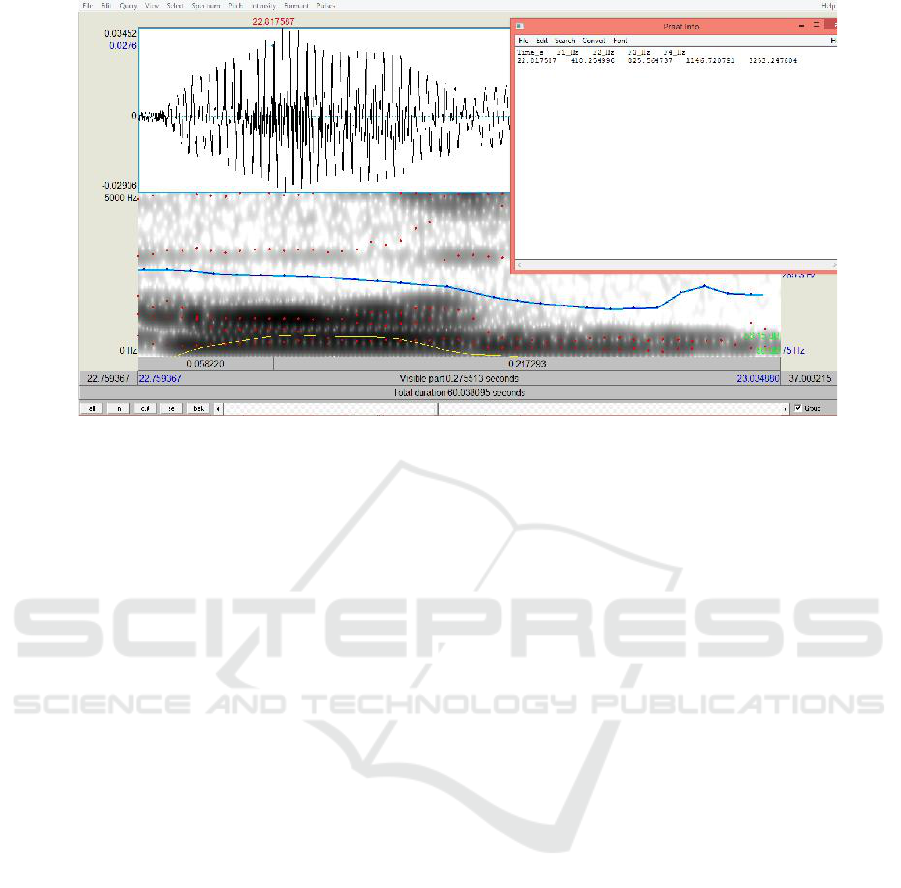

2.2 Data Analysis

The 240 tokens gathered from the learners’ recorded

data were analyzed through acoustic analysis. This

analysis used PRAAT as a tool that can measure the

vowels formants and durations. Only formant 1 (F1)

and 2 (F2) were measured for the purpose of this

study since these two formants are associated with the

height and frontness of the vowels (Ladefoged &

Maddieson, 1996) cited in Baart (2010: 66). These

formants were taken at the midpoint of the vowel

soundwave to ensure the pureness of the vowels (see

Figure 1). The durations, on the other hand, were

measured by considering the intensity and the

periodic shape of the soundwave as the characteristic

of vowels (Baart, 2010). The measured formants and

duration data were later logged in a spreadsheet file.

The data from the two of us were combined and the

mean from both data sources were used as the main

information. This information were imported into

PRAAT to create the vowel chart to answer the first

research question. Additionally, the numbers of the

formants and durations were calculated to get the

standard deviation to see the consistency of them. To

answer the second research question, the numerical

data of the formants and durations of each vowel

contrast were compared and t-tests were run to

investigate whether the learners of English contrast

the vowels.

Father as a Caregiver: The Thipology of Father Parenting Style While Mother doesn’t Exist and the Effect to Child Autonomy

59

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results from the acoustic analysis performed by

the two of us provided answers to the two research

questions. In this study, the formant frequencies were

set in Hertz and the durations were in milliseconds.

3.1 The characteristics of vowel contrast

production of Indonesian learners of

English

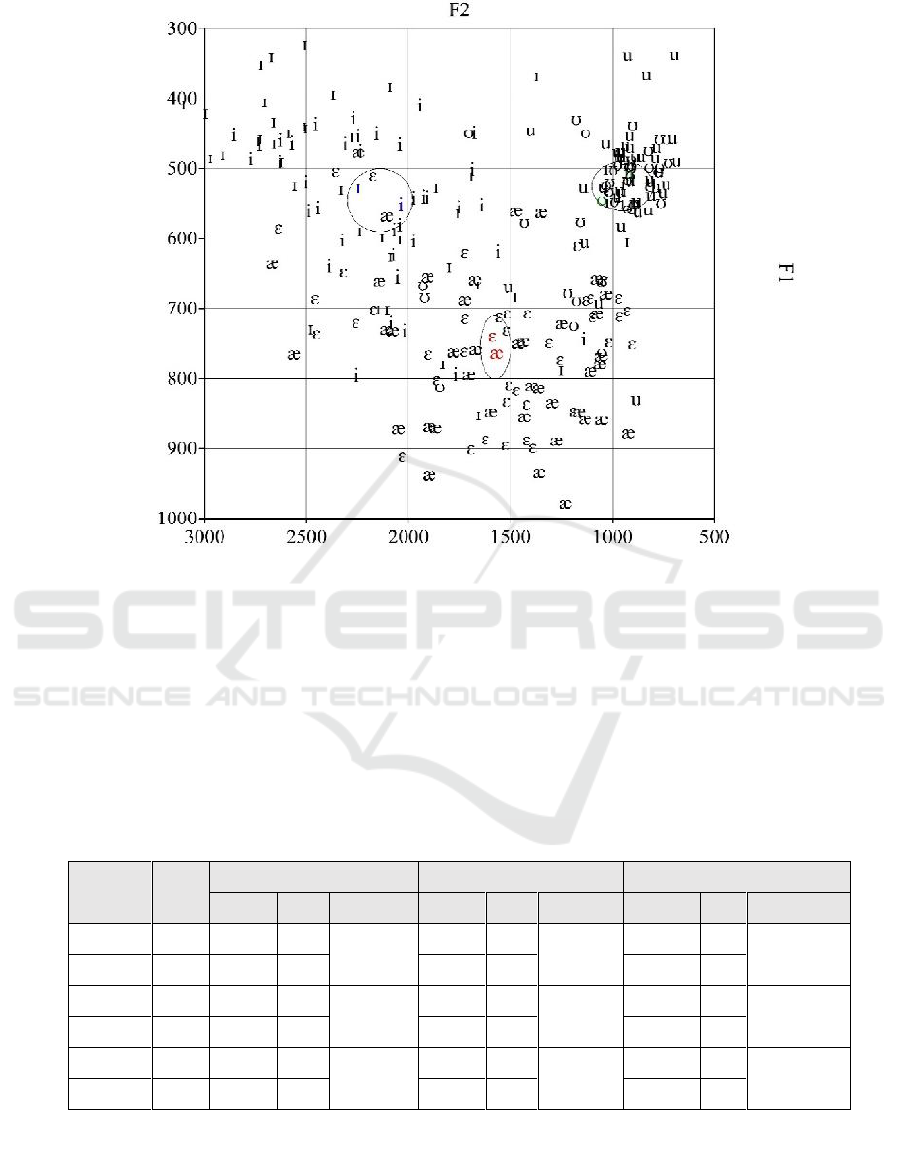

Figure 2 illustrates the dimension of the vowels

produced by the learners. The height is indicated by

F1 as the X axis, and the frontness is indicated by F2

as the Y axis. The average F1 and F2 are illustrated

by colors in the chart (red, blue and green) and are

placed in the circular shapes. The figure shows that

the learners tend to produce /i/ & /ɪ/ at the slightly

central part of the mouth. Supported by Table 1 which

provides statistical data indicating F1 (552 and 527)

and F2 (2038 and 2246) for the /i/ & /ɪ/ sounds. This

dimension is slightly different to those of the female

North American English (NAE) speakers. As found

by Peterson and Barney’s (1952) study that the

common dimension for female NAE speakers are 310

& 430 (F1); 2790 & 2480 (F2). Additionally, it is

interesting to find that the learners tend to have the

tense vowel /ɪ/ at a higher position that the lax vowel

/i/.

The /ɛ/ & /æ/ were produced at the lower center of

the mouth with the dimension of 739 & 763 (F1);

1587 & 1566 (F2). Compared to those of the female

NAE speakers, these sounds were more backward

because the female NAE speakers have F1 of 610 &

860 and F2 of 2330 & 2050. The /u/ & /ʊ/, on the

other hand, were produced at the lower back of the

mouth with the dimension of 506 & 544 (F1) and 918

& 1051 (F2). These dimensions are relatively similar

to those of the NAE speakers, except for the /ʊ/ sound

which was slightly lower. According to Peterson and

Barney (1952), the dimensions of /u/ & /ʊ/ for

females NAE speakers are 470 & 370 (F1) and 950 &

1160 (F2). Regardless the similarities found in the

dimensions of the average formant frequencies, the

standard deviation (shown in Table 1) indicates the

inconsistency of the formants. It can be seen in the

vowel chart (Figure 2) where the vowels are scattered

all over the place.

Regarding the duration of the vowels, the average

durations for /ɛ/,/æ/,/u/,/ʊ/,/i/ and /ɪ/ are 178 ms, 194

ms, 173 ms, 175 ms, 177 ms, and 185 ms

successively. It means the vowels produced by the

participants were relatively similar in terms of

duration. Additionally, similar to the dimension of the

vowels, the learners were also inconsistent with their

vowel duration indicated by the relatively high

standard deviations (see Table 1). It may indicate that

they did not have the sounds in their long-term

memory. However, this assumption needs further

investigation.

Figure 1: One of the who’d tokens analyzed in PRAAT to get the formants at the mid-point.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

60

3.2 The contrast of the lax and tense

vowels

To find out whether the learners contrasted the lax

and tense vowels, we interpreted the results from the

t-test. We set the statistical significance (α) at 1%. As

seen in Table 1, the results showed that the learners

did contrast the dimension of /u/ & /ʊ/ with the p-

value of 0.04 (F1) and 0.02 (F2), but they did not

contrast the durations (p-value=0.93). The /i/ and /ɪ/

were contrasted only by their frontness (p-value=

0.07), but not their height or F1 (p-value=0.34) nor

their durations (p-value=0.55). On the contrary, the

/ɛ/ and /æ/ were not contrasted at all. This support

what Figure 2 illustrates: the vowels are close to each

other and even overlapped.

It is interesting to find that these students

contrasted the place of articulation of /u/ and /ʊ/, but

not the other two vowel contrasts. It might be caused

by the fact that /i/, /ɪ/, /ɛ/, and /æ/ are neighboring

Figure 2: The vowel chart drawn in PRAAT to illustrate the height (F1) and frontness (F2) of the vowels.

Table 1: The statistical data of the formants and duration of the vowels.

Vowels

N

F1

F2

Duration

Mean

SD

p-value

Mean

SD

p-value

Mean

SD

p-value

ɛ

40

739

100

0.32

1587

479

0.84

178

60

0.22

æ

40

763

114

1566

445

194

54

u

40

506

70

0.04*

918

168

0.02*

173

63

0.93

ʊ

40

544

93

1051

310

175

69

i

40

552

100

0.34

2038

469

0.07*

177

61

0.55

ɪ

40

527

134

2246

548

185

64

α = 0.01

* significant

Father as a Caregiver: The Thipology of Father Parenting Style While Mother doesn’t Exist and the Effect to Child Autonomy

61

vowels. To prove this assumption, more studies

and/or more data are needed.

4 CONCLUSION

The results of the study show that Indonesian learners

do not really contrast the lax and tense vowels, except

for the dimension of one of the vowel contrasts. The

learners were inconsistent through most of the vowels

production in terms of articulation and duration.

There are many possible factors which may cause it,

such as the interference of their first language and/or

the lack of exposure to pronunciation. These

speculations, however, need further investigation.

Based on the findings of this study which appears to

be a support for the study conducted by Caromawati

& Muhammad (2016), it is important and necessary

for Indonesian learners of English to be exposed more

to pronunciation instruction, as suggested by Celce-

Murcia, Brinton, Goodwin, & Griner (2010). For

further direction, we think it is important to

investigate the roles of pronunciation instruction to

learners’ ability in differentiating the vowel contrast

such as a study conducted by Wang & Munro (2005).

In addition to that, it is also necessary to look at

Indonesian learners’ perception skills in

discriminating these vowel contrasts.

REFERENCES

Baart, J. L. 2010. A field manual of acoustic phonetics.

Dallas, TX: SIL International.

Brown, A. 1991. Functional load and the teaching of

pronunciation. In A.Brown (Ed.), Teaching English

Pronunciation: A book of readings. New York:

Routledge.

Caromawati, C., Muhammad, A. 2016. The monophtongal

English vowel production of Indonesian learners of

English with different proficiency levels. Iowa State

University, Ames, IA, USA.

Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D. M., Goodwin, J. M., &

Griner, B. 2010. Teaching pronunciation: A course

book and reference guide. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Deterding, D., Mohamad, N.R. 2016. The role of vowel

quality in ELF misunderstandings. Journal of English

as a Lingua Franca, 5(2). DOI: 10.1515/jelf-2016-

0021

Jenkins, J. 2000. The phonology of English as an

international language. UK: Oxford University Press.

Koffi, E. 2016. Relevant Acoustic Phonetics of L2 English:

Focus on intelligibility. Course Manuscript: St. Cloud

State University.

Maddieson, I., Ladefoged, P. 1996. The sounds of the

world’s languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peterson, G. E., Barney, H. L. 1952. Control methods used

in a study of the vowels. The Journal of the acoustical

society of America, 24(2), pp. 175-184.

Wang, X., Munro, M. J. 2004. Computer-based training for

learning English vowel contrasts. System, 32(4), pp.

539-552.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

62