Sharia in Secular State

The Place and Models for Practicing Islamic Law in Indonesia

Nurrohman Syarif, Tajul Arifin and Sofian Al-Hakim

UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung, Jl.AH Nasution 105,Bandung, Indonesia

{nurrohman, tajularifin64, sofyanalhakim}@uinsgd.ac.id

Keywords: Constitution, caliphate, ideology, Islamic state, legal system.

Abstract: In Islam, the complexity and uniqueness of relation of state and religion can be traced back in history of the

relation of Islamic law and state. The purpose of this study is to describe the place of Islamic law in Unitary

State of Republic Indonesia and the models or alternatives that can be used to practice Islamic law. This

research is a kind of non doctrinal qualitative legal research which included some problems, policy and law

reform based research. The subject of this study is the substance and norms of sharia that has been

accommodated by Indonesia legal system or has been applied through its protection. Data was collected

from the book or documents. From this study, it can be concluded that although officially, Indonesia is not

religious state, philosophically the purpose of sharia has been accommodated in Indonesia legal system,

legally there is no obstacle to absorb sharia values and norms into positive law as long as it is not contrary to

the constitution. This study also concluded that practically, there are some alternatives that can be used by

Muslims in practicing sharia. This result implies that there is no need for Muslim to establish an Islamic

theocratic state in order to practice comprehensive sharia.

1 INTRODUCTION

Relation of state religion is a complicated and

unique throughout its history. In Islam, the

complexity and uniqueness can be traced back in

early history of this religion. All Muslims agree to

made the prophet Muhammad SAW (Peace be Upon

Him) a role model for them. However, they differ in

determining what the main mission of the prophet

Muhammad is, and how to make the prophet a role

model?

Personally, Muhammad himself stated that he

was sent to complete morals. In other words, his

mission is ethical and moral not a political.

However, when he immigrated to Medina, he was

entrusted with the position that some experts

considered the position of a head of state.

Through his book entitled Muhammad Prophet

and Statesman, Montgomery Watt argues that

Muhammad was not only a Prophet but also a

statesman. (Watt, 1961: 94-95). This is a unique

role. Because it seems that Muhammad combined

spiritual religious as well as worldly political

authority. The impact of this uniqueness, experts are

different in many respects. For example, is the state

of Medina a religious or a civil state? Whether

Muhammad political or religious leader.

Ali Abd al-Raziq in his book Islam and The

Principles of Government (al-Islam wa Ushul al-

Hukmi) argued that the Prophet Muhammad

remained a moral leader not a political leader. (Abd

al-Raziq, 1985). But some other experts asserted that

Muhammad SAW, at Medina has actually become a

statesman or head of state.

In the modern age, Muslims broadly still divided

into two: a groups who want to make Islam as

political ideology and the other who want to place

Islam as a source of ethic, moral and spiritual

guidance. Further differences can be traced in

various things such as in determining the form of the

state of Medina; relation of religion and state;

relation of Islamic law and state; definition of

Islamic State; the way of Muslim countries placed

Islamic law in their respective constitutions of the

state; as well as the model of Islamic sharia

implementation in each country.

The Islamism movements that make Islam an

ideology both nationally and globally always pursue

the aspirations and demands to implement sharia

totally (kaffah) and formally through state

52

Syarif, N., Arifin, T. and Al-Hakim, S.

Sharia in Secular State - The Place and Models for Practicing Islamic Law in Indonesia.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Sociology Education (ICSE 2017) - Volume 2, pages 52-60

ISBN: 978-989-758-316-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

instruments. Islamism grows out of a specific

interpretation of Islam, but it is not Islam: it is a

political ideology that is distinct from the teaching

of the religion of Islam. (Tibi, 2012:1)

According to Pew Research Center (2013) there

are 72 % of Indonesian Muslims who favor making

Islamic law the official law in their country. In other

words, there are some Muslims who feel that legal

system of Indonesia not yet fully accommodate

sharia law.

The problem always arises when in its effort to

fight for the formalization or transformation of

Islamic law into national law, they use only one

model, the rigid, exclusive, conservative, literalist

one. Base on research by Pew Research Center

(2013) there are 45 % of Indonesian Muslims who

say hat sharia has single interpretation. Muslims

who hold this opinion tend to see the other

interpretation was wrong. As a result they prone to

be exploited by Islamism radical ideology who

always use sharia as one of their agenda. Survey

conducted by Pew Research Center (2015) finds that

4% of Indonesian Muslims supported the radical

ideology carried out by ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq

and Syria). If translated into real population, it is

about 10 million Muslims (Kompas, 2015). For

them, sharia cannot be fully implemented in

Indonesia because Indonesia is secular state.

Arskal Salim in his book Challenging the

Secular State; The Islamization of Law in Modern

Indonesia argues that attempts to formally

implement sharia in Indonesia have always been

marked by a tension between political aspirations of

the proponents and the opponents of sharia and by

resistance from the secular state. The result has been

that sharia rules remains tightly confined in

Indonesia. (Salim, 2008).

Contrary to what is said by Salim, this study

argues that what is tightly confined is just one of

several model of sharia implementation, that rigid

exclusive and literalist model. This study aims to

explain the place of Islamic law in Secular Unitary

State of Republic Indonesia and the models that can

be used to practice Islamic law.

The fundamental theory used in this research is

the theory of secular state presented by Ahmet T.

Kuru and the theory of the relationship between

Islam and state presented by Munawir Syadzali.

Ahmet T. Kuru, in his book Secularism and State

Policies toward Religion divided the state base on its

legislature and its policy toward religion into three

classifications; religious state such as Iran, Saudi

Arabia, Vatican, secular state and anti religious state

such as North Korea, China and Cuba. Secular state

can be divided into two: secular state with an

established religion and officially favor one like

Greece, Denmark, England, secular state that

officially favor none like United State, France,

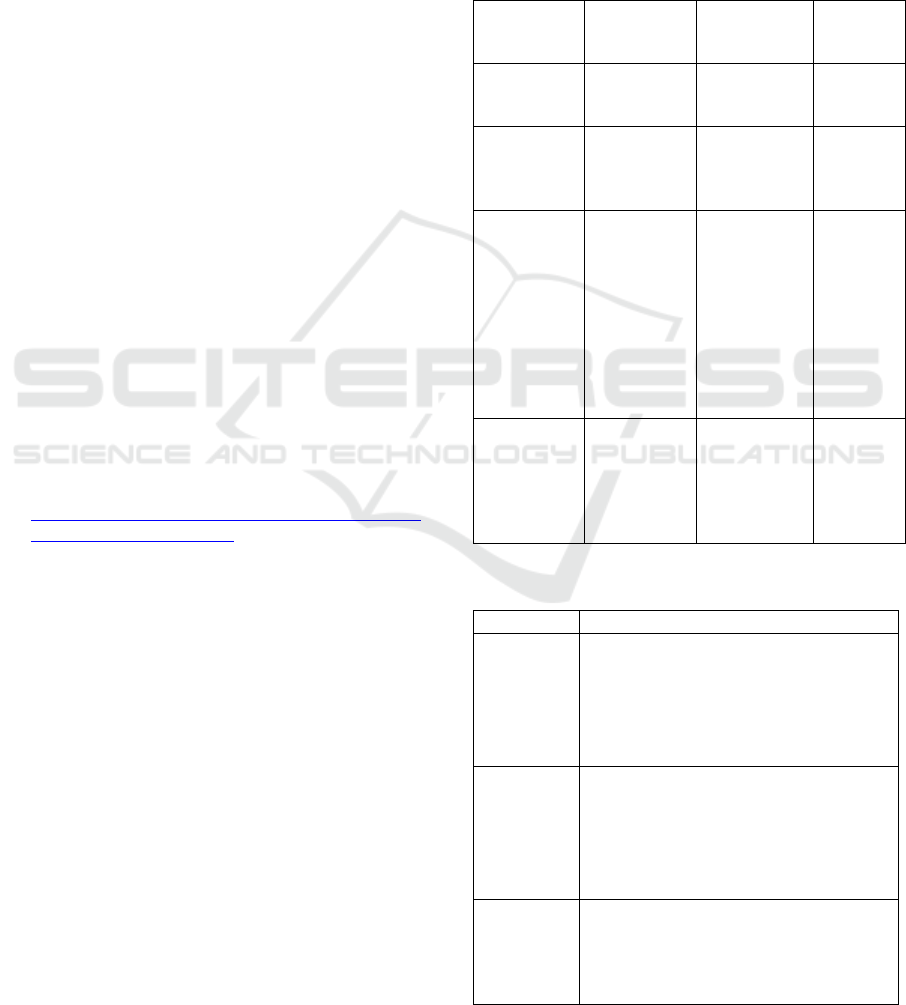

Turkey. (Kuru, 2009:8). See Table 1.

Lubna A Alam in his article Keeping The State

Out: The Separation of Law and State in Classical

Islamic Law said that the classical era of Islamic

history, which ended at the beginning of the

sixteenth century, saw the rise of Islamic states as

well as the formation of a complex system of Islamic

law. From its very beginnings, the content of Islamic

law developed largely free from political influence

and pressure (Alam, 2007).

Khaled Abou El Fadl in his article, Islam and the

State: A Short History said although, historically,

jurists played important social and civil roles and

often served as judges implementing the sharia and

executive ordinances, for the most part, government

in Islam remained secular. Until the modern age, a

theocratic system of government in which a church

or clergy ruled in God’s name was virtually

unknown in Islam. (Abou El Fadl, 2003:14).

According to Sjadzali, among Muslims there are

three schools of relations between Islam and the

state. Firstly, those who hold that Islam is not merely

a religion in the Western sense, that is, only

concerning the relationship between man and God,

Islam is a perfect religion that governs all aspects of

life, including the life of the state. Supporters of this

school include Hasan Al-Banna, Sayyid Qutub,

Muhammad Rashid Ridha and Al-Mawdudi.

Secondly, those who hold that Islam is a religion in

the Western sense, which has no relation to state

affairs. According to them, the Prophet Muhammad

was just an apostle like the previous apostles, with

the task of bringing people back to a glorious life

with high regard for noble character, and the prophet

was never meant to establish and head one country.

Supporters of this flow are Ali Abd al-Raziq and

Thaha Husein. Third, those who hold that in Islam

there is no constitutional system, but there is a set of

ethical values for the life of the state. Supporters of

this school include Mohammad Husein Haikal.

(Syadzali, 1990:1)

Theoretically or conceptually, sharia is God’s

Will in an ideal, general and abstract form, while

Islamic law (fiqh) is the product of human attempt to

understand God’s Will. Khaled Abou El Fadl in his

book Speaking in God's Name: Islamic Law,

Authority and Women, said that the sharia is God’s

Will in an ideal and abstract fashion, but the fiqh is

the product of the human attempt to understand

God’s Will. In this sense, the sharia is always fair,

Sharia in Secular State - The Place and Models for Practicing Islamic Law in Indonesia

53

just and equitable, but the fiqh is only an attempt at

reaching the ideals and purposes of sharia.

According to the jurists, the purpose of sharia is to

achieve the welfare of the people, and the purpose of

fiqh is to understand and implement the sharia.

(Abou El Fadl, 2014). In his book entitled Islam and

the Challenge of Democracy, Khaled Abou El-Fadl

said that sharia as conceived by God is flawless, but

as understood by human beings is imperfect and

contingent. (Abou El-Fadl, 2004:34) In his article,

Sharia in the Perspective of a Legal State Based on

Pancasila (Syariat Islam dalam Perspektif Negara

Hukum Berdasar Pancasila) Nurrohman Syarif said

that sharia or Islamic law has a number of

characters. First, it contains a sacred value and

personal because it comes from God and related to

faith. Secondly, it has a moral content. It doesn’t

only speak of rights and obligations but talk about

what should be or recommended to be done and

what should not be done through the inner

conscience by a mature and sane person (mukallaf).

The thirdly, Islamic law is not totally dependent on a

particular country. Because, it was developed by

legal experts independently. The fourth, Islamic law

is flexible and dynamic. Because it can basically

change if there is social change. It is dynamic

because it can develop in accordance with the

development of human civilization. The fifth, it is

rational, because it generally can be understood and

in line with common sense or scientific explanation.

(Syarif, 2016).

Although Islamic law is a ‘sacred

law’

, it is by no means essentially irrational; it was

created not by

irrational process of revelation but by

a rational method of interpretation, and the religious

standards and moral rules which were introduced

into the legal subject-matter provided the framework

for its structural order.( Schacht,1983:4)

In his book Philosophy of Islamic Law (Filsafat

Hukum Islam), Hasbi Ash Shiddieqy said that

Islamic law should be guided and developed based

on a number of principles, namely: 1) eliminate

narrow-mindedness (nafyu al-kharaj). 2) minimize

burden (qillatu al-taklif). 3) in line with human

welfare 4) realizing equitable justice 5) putting the

mind over the text of sharia in case of conflict

between the two. 6) each person assumes his own

responsibility. (Ash Shiddieqy, 1975: 73-92).

In his book Maqashid al-Shari’ah as Philosophy

of Islamic Law, A Systems Approach, Jasser Auda

quoted Ibn al-Qayyim’s (d. 748 AH/1347 CE)

statement: “Shari’ah is based on wisdom and

achieving people’s welfare in this life and the

afterlife. Shari’ah is all about justice, mercy,

wisdom, and good. Thus, any ruling that replaces

justice with injustice, mercy with its opposite,

common good with mischief, or wisdom with

nonsense, is a ruling that does not belong to the

Shari’ah, even if it is claimed to be so according to

some interpretation” (Auda,2007).

In general, the application model of Islamic

sharia in some countries can be divided into three

namely: exclusive-textual, inclusive-substantial, and

combination. These models cannot be separated

from the role of religion in politics. In his article,

Religion within The Nation of Pluralistic Society

(Agama dalam Pluralitas Masyarakat Bangsa,)

Masykuri Abdillah said the role of religion in

politics can be classified into three forms. Firstly,

religion as a political ideology; secondly, religion as

ethical, moral and spiritual base and third, religion

as sub-ideology. Countries that place religion as

ideology tend to practice religious teachings

formally as positive law and take a structural

approach to socialization and institutionalization of

religious teachings. Countries that place religion as

an ethical, moral, and spiritual source tend to

support cultural approaches and reject structural

approaches in terms of socialization and

institutionalization of religious teachings. This

means that the implementation of religious teachings

should not be institutionalized through legislation

and state support, but enough with the consciousness

of religious people themselves. Countries that place

religion as sub-ideology tend to support a cultural as

well as structural approach by involving religious

teachings in public policy making in a constitutional,

democratic and non-discriminatory manner.

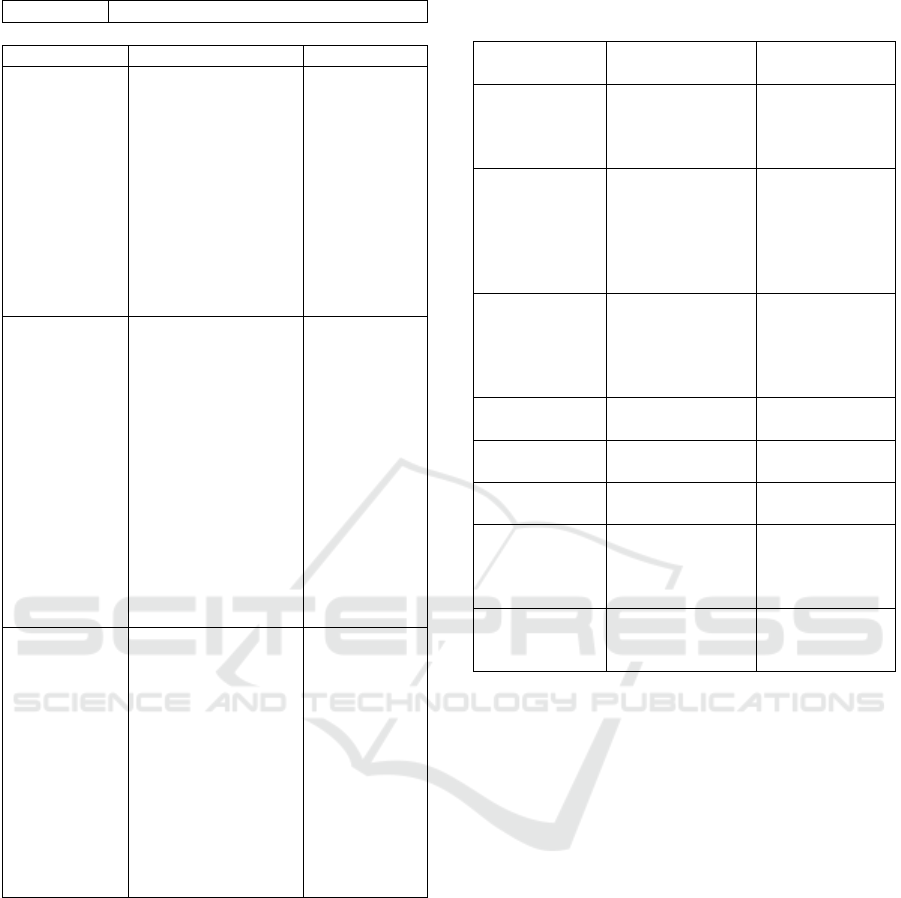

(Abdillah, 2000) See Table 2.

2 METHODS

This research is a kind of non doctrinal qualitative

legal research which covered some problems, policy

and law reform based research ((Dobinson and

Johns, 2007:20)

The subject of this study is the substance and

norms of sharia, both private and public, that has

been accommodated by Indonesia legal system or

has been practiced through its protection. Data was

collected from the book or documents that have been

published. The main data are drawn from the

Indonesian constitution (UUD 1945) and laws

designed to fulfil the aspirations of Muslims in

general or to fulfil the demands of political parties

that carry Islamic ideology. Data will be classified

and analyzed to explain the place of Islam and its

sharia in Indonesia legal system and the model for

practicing sharia in Indonesia. The place of sharia

ICSE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Sociology Education

54

was be analysed by comparing the constitution of

Indonesia with others. While the model of practicing

sharia was be analysed through cultural, structural

and combination model. This study was based on

assumption that practicing sharia is not the same

with formally implement sharia.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1

Results on the Place and Models for

Practicing Sharia

The study shows that although Indonesia is a secular

state, sharia occupies an important position in the

national legal system in Indonesia. The ideology of

the State of Indonesia is Pancasila. Literally, the

word Pancasila means five principles (from a

Sanskrit word: pance, five, and sila, principle). In

fact, the term Pancasila was used by Empu Prapanca

in his well-known book entitled Negarakertagama,

and likewise by Empu Tantular in his famous work

entitled Sutasoma. These two writers were great

thinkers and poets who lived under the Hindu

Kingdom of Majapahit during the reign of Hayam

Wuruk. (Ismail, 1995:4)

However, it can be accepted by Muslims as the

final ideology because all its principle in line with

Islamic teachings. Substantively, the objective of

Islamic law is to provide protection for freedom of

thought (hifdzu al-aqli), religious freedom (hifdzu

al-din), property rights (hifdzu al-mal), family rights

(hifdzu al-nasl) and the right to life (hifdzu al-nafs)

has been included in the Indonesian constitution.

The value of justice, benefit, wisdom and mercy had

also been included in the Indonesian Constitution.

Compared with the constitution of Medina, the

Indonesian constitution substantially contains a

number of the same principles such as the principles

of monotheism, unity and togetherness, equality and

justice, religious freedom, defending state,

preserving good tradition, supremacy of sharia and

the politics of peace and protection.

Like Pancasila which can be a paradigm for all

citizens in their life as citizens, sharia is also a

paradigm for all Muslims in private life and

community. If the sharia as ethical and moral

guidance for Muslims is born out of belief,

Pancasila is the ethical and moral guideline born

from the agreement of the founders of the nation.

In line with the role of religion in political life,

the model of Muslims in practicing sharia in

Indonesia can be divided into three, exclusive

textual, inclusive substantial, and combination.

The first model is usually trying to implement

sharia as mentioned in the text of the Qur'an, prophet

tradition or in the text of standard works recognized

by its authority in explaining Islamic law. This

model is based on the assumption that the sharia has

perfectly regulated all aspects of life. Sharia after the

prophet Muhammad no longer experiences the

process of evolution. Therefore, the duty of Muslims

is to apply it when the provisions are clear in the text

of the Qur'an or prophet tradition (al-Sunnah). If

there is no provision, then they can use analogy or

individual reasoning (ijtihad). Muslims do not need

to take other legal systems outside of Islam. Sharia

is a law of God that can not be known its true

content except by the experts, i.e. Jurist (faqih,

mujtahid). Therefore, any legislation made by a

legislature must be approved by a sharia expert, and

the sharia expert has the right to veto any laws

deemed inconsistent with the sharia. The first model

is commonly practiced privately in private matter.

The second model, it is try to practice the Islamic

sharia by looking at the concepts or ideas that exist

behind the text. If the main idea has been captured,

then its application can be carried out flexibly in

accordance with the times and places. This model is

based on the assumption that every legal provision

in Islamic law has its reasoning and purpose.

Therefore, the proponents of this model do not

object if Islamic law undergoes evolution. They are

also relatively easy to accept any legal system as

long as the legal system upholds justice, equality,

freedom, brotherhood and humanity which are the

core of sharia. Sharia is applied openly through

accepting "external elements" such as local custom

and thoughts coming from outside Islam. There is no

monopoly in the interpretation of sharia, and

therefore, there is no need for "sharia supervisory"

institutions that monopolize the interpretation of

sharia. The second model was commonly practiced

in public life.

The third model is combination. In practicing

sharia, they divided it into two; purely religious

teaching that should be done without any question or

reasoning ,( ta'abbudi) and what is understood by

reason ( ta'aqquli). They sort the sharia into two,

private and public. In private law, they tend to be

textual exclusives because it is part of ta'abudi, but

in public law, they tend to be substantially inclusive.

The choices taken by each person, community or

country will depend on the legal politics embraced

by them. See Table 3

Sharia in Secular State - The Place and Models for Practicing Islamic Law in Indonesia

55

3.2 Discussion on the Place and Models

for Practicing Sharia

Why philosophically, sharia occupies high level in

Indonesia legal system? Philosophically, the

substance of Islamic law is in line with the substance

contained in the Indonesian Constitution. The

constitution of Indonesia and the constitution of

Medina in the time of the prophet have the same or

similar principles according to Harun Nasution and

Munawir Sjadzali.

Harun Nasution, in his paper Islam and the

System of Government as Developing in History

(Islam dan Sistem Pemerintahan Sebagai yang

Berkembang dalam Sejarah) said that the principle

of monotheism is mentioned in article 22,23,42,47 in

Medina Charter, it also mentioned in the first

principle of Pancasila, article 9 and 29 of Indonesia

Constitution (UUD 1945). The principle of unity

and togetherness is mentioned in article 1,15,17,25

and 37 of Medina constitution as well as mentioned

in the third principle of Pancasila, article 1 verse 1,

article 35 and 36 of UUD1945. The principle of

equality and justice is mentioned in article 13, 15,

16,22,24,37 and 40 of Medina Constitution. It also

mentioned in the fifth principle of Pancasila, article

27, 31, 33 and 34 of Indonesia’s constitution. The

principle of religious freedom is mentioned in article

25 of Medina Constitution it also mentioned in

article 29 verse 2 of UUD 1945. The principle of

defending state is mentioned in article 24, 37, 38 and

44 of Medina constitution. It also mentioned in

article 30 of Indonesia’s constitution. The principle

of preserving good tradition is mentioned in article 2

until 10 of Medina constitution. It also mentioned in

article 32 Indonesia’s constitution. The principle of

supremacy of sharia is mentioned in article 23 and

42 of Medina charter. (The disputes are ruled based

Allah rules and the judgment of Muhammad SAW).

This principle is not explicitly mentioned in

Indonesia’s constitution, but religious norms was

adopted as logical consequence of implementing the

first principle of Pancasila and article 29 of

Indonesia’s constitution. The principle of politics of

peace and protection is mentioned in article

15,17,36,37,40,41,47 (peace and internal protection)

as well as in article 45 (peace and external

protection) of Medina constitution. In Indonesia’s

constitution, this principle mentioned in preamble,

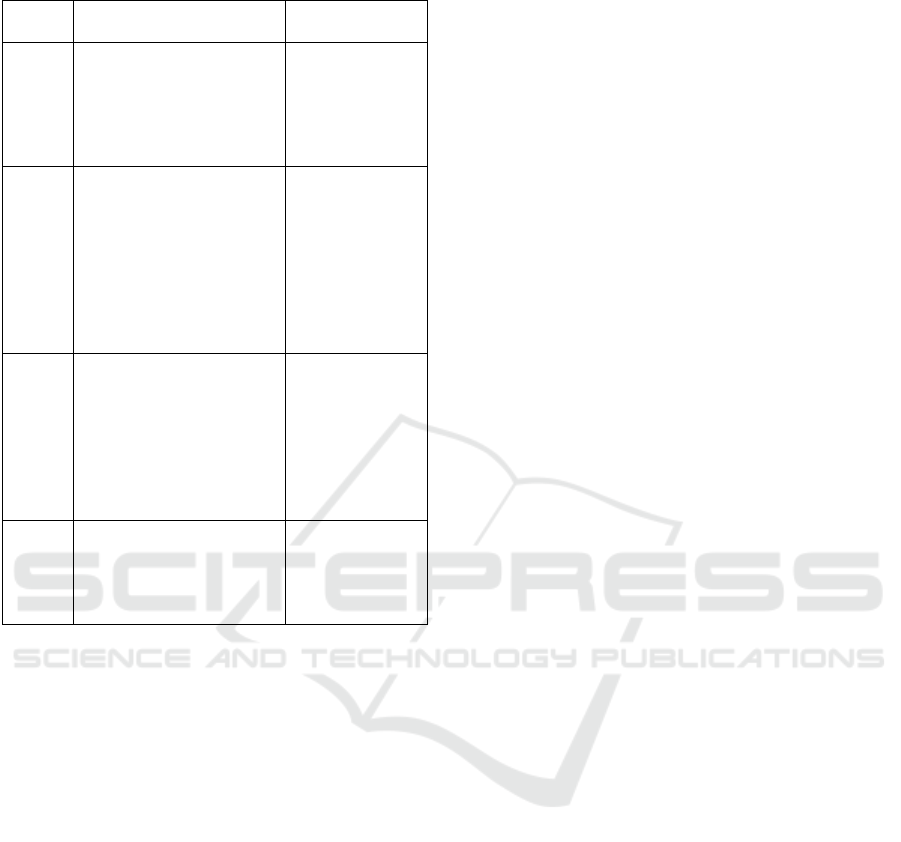

article 11and 13. (Nasution, 1985). See Table 4

Munawir Sjadzali, in his book Islam and

Government (Islam dan Tata Negara) said the

foundations laid down by Medina Charter as the

basis of state for the plural society in Medina are : 1)

all Muslims although from different ethnic or tribe

are one community 2) the relationship between

Muslims community and others is based on

principles (a) good neighboring (b) to help each

other in facing common enemy (c) defending who

are persecuted (d) giving advice to each other and

(e) respecting religious freedom. In addition,

Sjadzali said that Medina charter that often called by

many political scholars as the first constitution of

Islamic state not mentions state religion. (Sjadzali,

1990). In the Medina charter, the meaning of the

ummah is extended, it includes not only the Muslim

community but encompasses all citizens. (Al-Syarif,

1972)

If compared to other Muslim countries in placing

Islamic law in their constitution, Indonesia can be

paced in the third grade. (Nurrohman, 2002:17) See.

Table 5.

Indonesia is like Turkey in choosing secular state

for a Muslim-majority society. In fact, in the Muslim

world, twenty out of forty-six Muslim-majority

states are secular, including Indonesia, as they at

least, do not declare Islam as official religion, and

Islamic law does not control their legislative and

judicial processes. (Kuru, 2009). However, in

Indonesia Islamic law has entered into the life of the

state through structural and cultural processes,

through the transformation of values, norms or

symbols. As a source of ethics, morals and

spirituality, sharia for Muslims is a living paradigm

that can enter into various aspects of life, including

when they live in a secular state.

There is no correlation between the degrees of

state in placing the sharia formally in their

constitution with the degree of the state in practicing

sharia. For instance, although Indonesia placed only

in the third grade, but the values of sharia which are

practiced in Indonesia are better than Iran. Base on

Islamicity index made by Rehman and Askari,

Indonesia ranked at 140, higher than Pakistan that

ranked at 147, Egypt 153, and Iran at 163. (Rehman

and Askari: 2010). This is because sharia actually

can be flexibility practiced as long as it is directed to

achieve its purpose.

The acceptance of Muslims to the secular state

with Pancasila as its ideology, in which the word

sharia is not mentioned, not a one-off process, it

requires a long process as described by Faisal Ismail

(Ismail, 1995). Concerning the diversity of Muslims

in practicing sharia, H.A.R.Gibb as quoted by

Hamid Enayat said that in the Sunni community

there is no one universally accepted doctrine of

caliphate. What is does lay down is a principle: that

caliphate is that form of government which

safeguards the ordinances of sharia and sees that

they are put into practice. So long as that principle is

applied, there may be infinite diversity in the manner

of its application. (Enayat, 1982). Theocratic

caliphate cannot be accepted in a country that has

ICSE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Sociology Education

56

embraced the principle of democracy like Indonesia.

(Nurrohman, 2007)

Therefore, it is true when Hallaq said that the

idea of the Islamic State in the form of a theocratic

caliphate in a modern democratic country is an

impossible. (Hallaq, 2013). Because it will hinder

the emergence of what is called “pragmatic

eclecticism” in Islamic law. (Ibrahim, 2015:10).

Viewed from general legal system in the world,

what is going on in legal policy in Indonesia is what

is described by Palmer, Mattar and Koppel as a

mixed legal system, a legal system that combines

civil law, common law, customary law and Islamic

law. Under these conditions, all legal systems have

an opportunity to contribute. (Palmer, Mattar and

Koppel, 2015:279). So, the problem for practicing

sharia in Indonesia actually only belong to parties

who will imposed sharia formally, literally, and

structurally through the instrument of the

authoritarian state.

In Indonesia, a number of experts have different

views in explaining the theory of how the sharia is

applied in the context of the national legal system.

Juhaya S Praja for instance, mentioned various

theories such as credo theory, the theory of legal

authority and the theory of reception in complex.

According to these theories a Muslim is obliged to

implement all Islamic law as a consequence of his

creed. Islamic law is fully applicable to Muslims,

because they have embraced Islam even though in

practice there are still deviations. This theory

became a reference in the colonial policy since 1855.

(Praja, 2009: 107),

Christian Snouck Hurgronye (1857-1936)

developed a theory called receptive theory.

According to Hurgronye, Islamic law in Indonesia

only applies if customary law requires it. This theory

became the reference of colonial policy since 1929

through the Indische Staatsregeling of 1929 Article

134 paragraph 2.

A Qadri Azizy developed the theory which he

called the theory of the positivization of Islamic law.

According to this theory, the application of Islamic

law is no longer determined on the basis of

acceptance by customary law. Because Islamic law

has basically become a positive law for Indonesian

Muslims. The main reference of this theory is: UU

No.1 th 1974 about marriage, PP No.28 of 1977 on

Endowment (Perwakafan), Law Number 7 of 1989

on Religious Courts, Presidential Decree No.1 of

1991 on Islamic Law Compilation, Law No.17 of

1999 on Zakat Management.

4 CONCLUSIONS

From this study it can be concluded that Indonesia

remains a secular state. Although philosophically,

Islamic law occupies an important position in

Indonesia legal system but formally in the

constitution, the word sharia or Islamic law was not

mentioned. However, Muslims have a great

opportunity to practice Islamic law fully as long as

they use many alternatives. There are many models

for practicing sharia in Indonesia.

As a source of ethics, morals and spirituality, the

sharia for Muslims is a paradigm. When viewed

from philosophical perspective what happens in

Indonesia is the sharia-ization of Pancasila or

Islamization of law, but when viewed from formal

legal perspective, what happens is Pancasila-ization

of sharia. For all laws and regulations promulgated

in Indonesia must be openly prepared to be tested in

conformity with the constitution.

This study impacted that Muslims in Indonesia

didn’t need a theocratic state of caliphate. This study

also impacted that Indonesian Muslim didn’t need

Islamic Ideology to replace Pancasila as state

ideology. Because, by following the provisions and

principles contained in the constitution of Indonesia,

Muslims in Indonesia has actually followed the

Prophet Muhammad model in state affairs. Further

research is directed to identify how the values

contained in Pancasila and sharia are practiced by

the Indonesian people, including by Muslims, in

everyday life.

REFERENCES

Abou El Fadl, K. 2003. Islam and the State: A Short

History in Khaled M. Abou El Fadl et al. Democracy

and Islam in the New Constitution of Afghanistan.

Abou El Fadl, K. et al. 2004. Islam and the Challenge of

Democracy. Princeton University Press.

Abou El Fadl, K. 2014. Speaking in God’s Name: Islamic

Law, Authority and Women. England: Oneworld

Publications.

Abdillah, M. 2000. Religion within The Nation of

Pluralistic Society (Agama dalam Pluralitas

Masyarakat Bangsa) in Kompas February 25, 2000.

Abd al-Raziq, A. 1985. Islam and The Principles of

Government (al-Islam wa ushul al-Hukm), translated

to Indonesia, Khilafah dan Pemerintahan dalam

Islam. Bandung: Pustaka.

Alam, L. A. 2007. Keeping The State Out: The Separation

of Law and State in Classical Islamic Law Michigan

Law Review 105 (6) pp. 1255.

Ash Shiddieqy, H. 1975. Filsafat Hukum Islam. Jakarta,

Bulan Bintang.

Auda, J. 2007. Maqasid al-Shari’ah as Philosophy of

Sharia in Secular State - The Place and Models for Practicing Islamic Law in Indonesia

57

Islamic Law, A Systems Approach. London,

Washington: The International Institute of Islamic

Thought,

Dobinson, I., Johns, F. 2007 Qualitative Legal Research in

Mike McConville and Wing Hong Chui, ed., Research

Methods for Law, Edinburgh University Press.

Enayat, H. 1982. Modern Islamic Plitical Thought: The

Response of the Shi’i and Sunni Muslims to Twentieth

Century, London, The Macmillan Press LTD, page 14.

Hallaq, W. B., 2013. The Impossible State: Islam, Politics,

and Modernity’s Moral Predicament, Columbia

University Press.

Ibrahim, A. F., 2015. Pragmatism in Islamic Law. A

Social and Intellectual History, Syracuse University

Press.

Ismail, F., 1995. Islam, Politic and Ideology in Indonesia:

A Study of The Process of Muslim Acceptance of The

Pancasila, a dissertation, Institute of Islamic Studies,

McGill University, Montreal.

Kuru, A. T. 2009. Secularism and State Policies toward

Religion: The United States, France, and Turkey,

Cambridge University Press, page 8.

Nasution, H. 1985.

Islam and the System of

Government as Developing in History (Islam dan

Sistem pemerintahan Sebagai yang Berkembang

dalam Sejarah) in Studia Islamika, Nomor 17 tahun

VIII.

Nurrohman dkk, 2002. Sharia, Constitution and Human

Rights: Study on The View of Acehnese Figures on The

Model of Sharia Implementation (Syari’at Islam,

Konstitusi dan Hak Asasi Manusia: Studi terhadap

Pandangan Sejumlah Tokoh tentang Model

Pelaksanaan Syari’at Islam di Daerah Istimewa

Aceh), Bandung: Lembaga Penelitian IAIN

Nurrohman, 2007. Questioning theocratic caliphate, The

Jakarta Post, August 24, 2007. Available online at:

http://pancasilaislam.blogspot.co.id/2010/02/questioni

ng-theocratic-caliphate.html accessed, October 7,

2017.

Palmer, V. V., Mattar, M. Y., Koppel, A., ed., 2015.

Mixed Legal System, East and West, Ashagate

Publishing Company.

Praja, J. S. 2009. Theories on Islamic Law: Comparative

Study with Philosophical Approach (Teori-teori

Hukum Islam: Suatu Telaah Perbandingan dengan

Pendekatan Filsafat, Bandung, Program Pascasarjana

Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN).

Rehman, S. S., Askari, H. 2010. How Islamic are Islamic

Countries, Global Economy Journal 10(2).

Salim, A., 2008. Challenging the Secular State; The

Islamization of Law in Modern Indonesia, University

of Hawai‘i Press.

Schacht, J., 1983. An Introduction to Islamic Law, Oxford

University Press, USA.

Sjadzali, M., 1990. Islam and Government (Islam dan

Tata Negara), Jakarta. UI Press.

Al-Syarif, A. I., 1972. The Prophet’s State in Medina

(Daulat al-Rasul fi al-Madinah), Mesir, Dar al-

Maarif.

Syarif, N, 2016. Sharia in The Perspective of Legal

System Base on Pancasila (Syariat Islam dalam

Perspektif Negara Hukum berdasar Pancasila)

Pandecta, Research Law Journal 11 (2) pp. 160-173.

Tibi, B., 2012. Islamism and Islam. Yale University Press.

Watt, M. 1961. Muhammad Prophet and Statesman,

Oxford University Press.

APPENDIX

Table 1: The types of state according to Ahmed Kuru.

Religious

state

Secular State Anti

Religious

state

Legislature

and

judiciary

Religious

based

Secular Secular

The state

toward

religion

Officially

favour one

Officially

favour one

or none

Officially

hostile to

all or

man

y

Examples Iran, Saudi

Arabia,

Vatican

Greece,

Denmark,

England

(officially

favor one)

United State,

France

,Turkey

(officially

favor none

)

North

Korea,

China,

Cuba

Number of

the state

12 60

(Officially

favour one)

120

(Officially

favour none

)

5

Table 2: The role of religion in politics according to

Masykuri Abdillah.

Types Description

Religion as

Political

Ideology

Countries that place religion as ideology

tend to practice religious teachings

formally as positive law and take a

structural approach to socialization and

institutionalization of religious

teachings.

Religion as

ethical,

moral and

spiritual

base

Countries that place religion as an

ethical, moral, and spiritual source tend

to support cultural approaches and reject

structural approaches in terms of

socialization and institutionalization of

religious teachings.

Religion as

sub-

ideology

Countries that place religion as sub-

ideology tend to support a cultural as

well as structural approach by involving

religious teachings in public policy

makin

g

in a constitutional, democratic

ICSE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Sociology Education

58

and non-discriminator

y

manner.

Table 3: The models for practicing Sharia.

Descri

p

tion Assum

p

tions

Exclusive

textual

trying to implement

sharia as mentioned

in the text of the

Qur'an, the prophet

tradition or in the

text of standard

works of expert

recognized by its

authority in

explaining Islamic

law

Sharia has

perfectly

regulated all

aspects of

life. Sharia

after the

prophet

Muhammad

no longer

experiences

the process of

evolution

Inclusive

substantial

Trying to practice

sharia by looking at

the concepts or ideas

that exist behind the

text. If the main idea

has been captured,

then its application

can be carried out

flexibly.

Every legal

provision in

Islamic law

has its

reasoning and

purpose.

Therefore,

Islamic law

undergoes

evolution.

There is no

monopoly in

the

interpretation

of sharia.

Combination In practicing the

sharia, they divided

it into purely

religion (ta'abbudi)

and ta'aqquli (be

understood by

reason). They sort

the sharia into two,

private and public.

Some sharia

has a reason

and

experiences

evolution, and

the other ones

are should

accepted

without

reason and

not

experience

evolution

Table 4: The comparison between Indonesia constitution

and medina charter according to Harun Nasution.

The elements

of

Medina Charter Indonesia

Constitution

(1)Monotheism Article

22,23,42,47

The first

principle of

Pancasila, and

article 9, 29

(2) Unity and

togetherness

Article

1,15,17,25,37

The third

principle of

Pancasila,

article 1 verse

1, article 35,

and 36

(3)Equality

and justice

Article

13,15,16,22,23,

24,37,40

The fifth

principle of

Pancasila,

article

27,31,33,34

(4)Religious

freedo

m

Article 25 Article 29

(5) Defending

state

Article

24,37,38,44

Article 30

(6) Preserving

good tradition

Article

2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10

Article 32

(7) Supremacy

of sharia

Article 23,42 The first

principle of

Pancasila, and

article 29

(8) Politics of

peace and

p

rotection

Article

15,17,36,37,40,

41,45,47

Preamble of

constitution and

article 11,13

Sharia in Secular State - The Place and Models for Practicing Islamic Law in Indonesia

59

Table 5: The place of Sharia in the constitution of Muslim

countries according to Nurrohman.

The

g

rade

The position of sharia Example of

the state

1 A country whose

constitution recognizes

Islam as a state religion

and makes sharia the

main source of legislation

Saudi Arabia,

Libya, Iran,

Pakistan and

Egypt

2 A country whose

constitution declares

Islam as a state religion

but does not mention

sharia as the main source

of legislation means that

sharia is only seen as one

source of some legal

sources of le

g

islation

Iraq and

Malaysia.

3 A country that does not

make Islam a state

religion and does not

make sharia the main

source of legislation but

recognizes the sharia as a

living law in the

community.

Indonesia

4 States that declare

themselves as a secular

state and seek to make the

Islamic sharia not affect

its le

g

al s

y

stem.

Turkey

ICSE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Sociology Education

60