An Online Assessment and Feedback Approach in Project Management

Learning

Ana Gonz

´

alez-Marcos

1

, Fernando Alba-El

´

ıas

1

and Joaqu

´

ın Ordieres-Mer

´

e

2

1

Department of Mechanical Engineering, Universidad de La Rioja, c/ San Jos

´

e de Calasanz 31, 26004 Logro

˜

no,

La Rioja, Spain

2

PMQ Research Group, ETSII, Universidad Polit

´

ecnica de Madrid, Jos

´

e Guti

´

errrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain

Keywords:

Assessment, Feedback, Project Management, Higher Education.

Abstract:

This work presents an online system to facilitate the assessment and feedback in project management edu-

cation. Students are involved in real-world engineering projects in order to promote professional project

management learning. Thus, students share an experience in executing and managing projects and are able to

put into practice different skills and competences that a project member should possess in the development of

a project. The proposed system considers competence assessment through different pieces of evidence that are

pertinent to each assessed competence. Information from the three main actors in learning activities (teacher,

peer, and learner) is collected by means of specifically developed online forms. All the gathered evidences

are considered in a weighted integration to yield a numerical assessment score of each competence that is

developed for each student. Furthermore, three different types of feedback are implemented and provided se-

veral times in order to promote and improve students’ learning. Data analysis from a specific academic course

suggest that the presented system has a positive impact on students’ academic performance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Assessment can strongly influence the learning pro-

cess. In fact, it is well-known that what influence

students most is not the teaching but the assessment

(Snyder, 1971; Miller and Parlett, 1974; Black and

Wiliam, 1998; Gibbs and Simpson, 2004; Andersson

and Palm, 2017). Each assessment has different go-

als and occurs in specific contexts, and the design

must adapt to changing circumstances, while meeting

the challenges of scientific credibility (Tridane et al.,

2015). In the academic literature, two major forms of

assessment are identified:

• Summative assessment or assessment of lear-

ning, which measures a student’s learning at the

end of a period of instruction. In general, summa-

tive assessment includes scoring for the purposes

of awarding a grade or other forms of accredita-

tion (Gikandi et al., 2011). This is the traditional

and conventional form of assessment.

• Formative assessment or assessment for lear-

ning, which is concerned with the promotion of

learning during a period of instruction. Research

shows that formative assessment can be related

to self-regulated learning (Nicol and Macfarlane-

Dick, 2006; Black and Wiliam, 2009; Clark, 2012;

Meusen-Beekman et al., 2016), which can be des-

cribed as ”an active, constructive process whereby

learners set goals for their learning and attempt to

monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, mo-

tivation, and behavior, guided and constrained by

their goals and contextual features in the environ-

ment” (Pintrich, 1999).

Formative assessment is, without a doubt, a po-

werful tool to positively impact on students’ learning

and achievements. According to Black and Wiliam

(2009), there are five key strategies for implementing

formative assessment:

1. Clarifying and sharing learning intentions and cri-

teria for success;

2. Engineering effective classroom discussions and

other learning tasks that elicit evidence of student

understanding;

3. Providing feedback that moves learners forward;

4. Activating students as instructional resources for

one another; and

5. Activating students as the owners of their own le-

arning.

González-Marcos, A., Alba-Elías, F. and Ordieres-Meré, J.

An Online Assessment and Feedback Approach in Project Management Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0006367500690077

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 2, pages 69-77

ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

69

These strategies involve the three main actors

in learning activities: teacher, peer, and learner.

Furthermore, they are consistent with other studies

that examine different mechanisms for providing for-

mative assessment, such as feedback (Shute, 2008;

Strudwick and Day, 2015), self-assessment (Panadero

et al., 2014; Ross, 2006), and peer-assessment (Gielen

et al., 2010; van Zundert et al., 2010).

Aligned with the five strategies put forth by Black

and Wiliam (2009), this paper presents an online sy-

stem for assessment and feedback in Project Manage-

ment education beyond the stage reached in our pre-

vious work (Gonz

´

alez-Marcos et al., 2015). The que-

stion to be addressed is the following:

• Does the proposed system for assessment and

feedback promote students to improve their aca-

demic performance?

The organization of the remainder paper is as fol-

lows: Section 2 is dedicated to briefly describe the

designed assessment and feedback system. Section 3

presents how the system is implemented. Section 4

provides the results observed in the academic course

analyzed. Finally, Section 5 discusses some general

conclusions and presents future work.

2 THE ASSESSMENT AND

FEEDBACK SYSTEM

Our previous work on assessment of project mana-

gement competences (Gonz

´

alez-Marcos et al., 2015)

focused on the methodology for gathering and inte-

grating information about the individual performance

of students in order to obtain numerical assessment

values of each competence. The purpose of this paper

is to present an improved version of our assessment

and feedback system, as well as to analyze its impact

on students’ academic performance.

As mentioned in the previous section, the propo-

sed online system is based on the five key strategies

identified by Black and Wiliam (2009) because our

goal is to carry out formative assessment. How those

strategies are implemented is explained below.

1. Clarifying and sharing learning intentions and

criteria for success

The course contains the following materials:

• Assessment procedures and instruments. This do-

cument presents the competences to be assessed

during the semester, the instruments (forms, au-

dits, etc.) used to collect information, and how

all this information is integrated to provide indi-

vidual scores for the assessed competences. Furt-

hermore, it explains how the feedback is provided.

• Specific procedure manuals that describe the re-

sponsibilities of each role, explain how to operate,

how to do things, how to communicate mandatory

information, etc.

• Quality criteria for management products. This

document defines the requirements that the mana-

gement products created during the project should

fulfill.

• Quality criteria for management processes. This

document provides the quality criteria for what is

considered good practice standards.

• Assessment checklists and rubrics used to assess

the project management competences.

The first module of the course is dedicated to ex-

plain the methodology that will be used during the

semester, as well as to clarify goals and success cri-

teria. Thus, students become familiar with the course

objectives and requirements for success from the be-

ginning of the semester, besides basic project mana-

gement concepts or the use of the web-based learning

environment.

2. Engineering effective classroom discussions

and other learning tasks that elicit evidence of

student understanding

In order to be aligned with the real environment in

project management and provide an authentic context,

students are involved in real-world engineering pro-

jects. These projects are oriented to learning about

the professional project management methodology

PRINCE2

TM

(Project IN Controlled Environments)

(Office Of Government Commerce, 2009). According

to this methodology, a project is split into multiple

phases or stages that do not overlap (Figure 1). Be-

tween each phase the outcome of the prior phase is

evaluated and it is considered if the plans for the up-

coming phase might need to be modified.

Students, as in professional projects, assume dif-

ferent roles with different responsibilities in the pro-

ject team. Thus, they adopt an active role during the

learning process and are able to put into practice dif-

ferent skills and competences that a project member

(project manager, team manager, etc.) should possess

in the development of a project.

In summary, students are situated in a project de-

velopment process that is interesting and useful to

them and in which their individual differences are

considered. Furthermore, self-directed learning, lear-

ning by doing and a sense of responsibility are fos-

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

70

Directing

Starting

Up a

Project

Directing a Project

Initiating a Project Controlling a Stage Controlling a Stage

Managing Product

Delivery

Managing Product

Delivery

Managing

a Stage

Boundary

Closing a

Project

Managing

Delivering

Pre-project

Initiation Stage

(IS)

Subsequent Delivery

Stage(s) (DS)

Final delivery Stage

(FS)

Managing

a Stage

Boundary

Figure 1: The PRINCE2 Process Model (Source: Office Of Government Commerce, 2009).

tered. A detailed description of the learning envi-

ronment adopted can be found in (Gonz

´

alez-Marcos

et al., 2016).

3. Providing feedback that moves learners

forward

Within the literature there is general agreement that

high quality feedback to students on their assessments

is important and is of benefit to their future lear-

ning (Strudwick and Day, 2015). Feedback is not

only regarded as crucial to improve knowledge and

skill acquisition, i.e. achievement, but also depicted

as a significant factor in motivating learning (Shute,

2008).

It is also recognized that effective feedback is not

only based on monitoring progress toward the speci-

fic learning goals but also focuses students on speci-

fic strategies for improvement (Brookhart et al., 2010;

Gikandi et al., 2011). Consequently, effective feed-

back should deliver high quality information to stu-

dents about their learning, as well as provide oppor-

tunities to close the gap between current and desired

performance, among others (Nicol and Macfarlane-

Dick, 2006).

In our case, there are three different types of feed-

back provided to students about their performance:

• Feedback on student activities within the develo-

ped web-based environment. An auditing tool was

developed to automatically check the integrity of

performed actions and procedures, such as work

planning and proper effort allocation, document

consistency, correct use of the collaborative tools,

etc. Students are able to order an online self-audit

based on these automatic checks at any time. The-

refore, they can identify their mistakes and im-

prove their performance.

• Feedback on the contribution of each product

or procedure to the effort claimed by each stu-

dent. Students can gather detailed –tabular and

graphical– information about what product(s) and

competence(s) affected their current scores. This

information is provided at least three times du-

ring project execution (one per project life cycle

phase).

• Lessons learned. Also conducted at the end of

each project phase, a lessons learned review is

provided to each project through the web-based

environment. This report, which is based on ac-

tual project performing, identifies good and poor

practices over the course of each project phase.

Furthermore, each lessons learned report is ana-

lyzed in specific sessions to collectively discuss

what is working and what is not working well. It

is not possible to rebuild the already delivered and

approved items, but this feedback provides advice

on how to proceed and how to improve in the fu-

ture.

4. Activating students as instructional resources

for one another

Peer-assessment can be defined as an arrangement in

which individuals consider the amount, level, value,

worth, quality, or success of the products or outco-

mes of learning of peers of similar status (Topping,

1998). Although peers are not domain experts, the

use of peer-assessment and feedback can be beneficial

for learning, not only for the receiver but also for the

peer assessor (van den Berg et al., 2006; Gielen et al.,

2010; Ten

´

orio et al., 2016; Topping, 1998). Further-

more, peer-assessment can be regarded as a form of

collaborative learning (Falchikov, 2001; van Gennip

et al., 2010).

An Online Assessment and Feedback Approach in Project Management Learning

71

In our case, each student is assessed by all the ot-

her students of the project interacting with the stu-

dent in question for a given competence. The peer-

assessment is carried out by means of different forms,

by means of at least one piece of evidence clearly ha-

ving those criteria determining the maximum degree

of performance specified therein. Thus, the propo-

sed system collects evidence-based opinions about the

products being produced and how the team is mana-

ging the project.

5. Activating students as the owners of their own

learning

Findings from research conducted on self-assessment

(Andrade and Du, 2007; Boud, 1995; Panadero et al.,

2014; Ross, 2006) show that self-assessment contri-

butes to higher student achievement and improved be-

havior. Since self-assessment requires students to re-

flect on their own work and judge the degree to which

they have performed in relation to explicitly stated go-

als and criteria, they have the opportunity to identify

strengths and weaknesses in their work (Andrade and

Du, 2007) and, thus, what constitutes a good or poor

piece of work.

Taking into account that self-assessment can have

positive benefits for the students’ learning process, the

proposed assessment and feedback system also consi-

ders the opinions from those students who produce a

product or are responsible for its process implemen-

tation.

In summary, our proposal gathers information

from the three main actors in learning activities (te-

acher, peer, and learner) to assess each student’s per-

formance. Therefore, the proposed assessment and

feedback system uses some kind of 360-degree over-

view of different activities inside the project. All the

collected evidences are considered in a weighted inte-

gration to yield a numerical assessment score of each

competence that is developed for each student.

3 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE

PROPOSED ONLINE SYSTEM

The online assessment and feedback system was cre-

ated by integrating information gathered from the fol-

lowing open source tools:

• A project and portfolio management software

(http://www.project.net) that provides the neces-

sary project management tools, as well as some

collaborative tools such as blogs, document repo-

sitory, etc. The lessons learned reports mentio-

Figure 2: Partial view of an audit report with data automa-

tically gathered from a project.

ned in Section 2 are provided through the project’s

blog of this web-based software.

• A survey collector (https://www.limesurvey.org)

that contains the designed forms to conduct the

proposed assessments. Teachers, learners and

peers use the same assessing forms.

The developed assessment and feedback tool

(P2ML) – which was build by means of CakePHP

(http://cakephp.org) – was designed to communicate

with the aforementioned open source tools and to pro-

vide feedback as described in Section 2. The first type

of feedback is based on student activities within the

developed web-based environment. Figure 2 shows a

partial view of the audit report about the integrity of

performed actions and procedures that each student

can order at any time. Text is displayed in red when

the system identifies mistakes, inconsistencies or in-

appropriate behaviors.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

72

The second type of feedback is concerned with the

contribution of each product or procedure to the effort

claimed by each student. Detailed information about

students’ performance is updated at least at the end of

each project phase. Thus, besides tabular information,

different graphical views are provided to illustrate the

performance evolution of each student:

• First, each student is able to identify what project

management competences were developed during

the project execution, as well as to compare his

or her performance to the average of the students

with the same role. In the case of the propo-

sed system, the reference framework used as a re-

ference for competences was the IPMA Compe-

tence Baseline (ICB) (Caupin et al., 2006). The

IPMA Competence Baseline is the common fra-

mework document that all IPMA Member Asso-

ciations and Certification Bodies abide by to ens-

ure that consistent and harmonized standards are

applied.

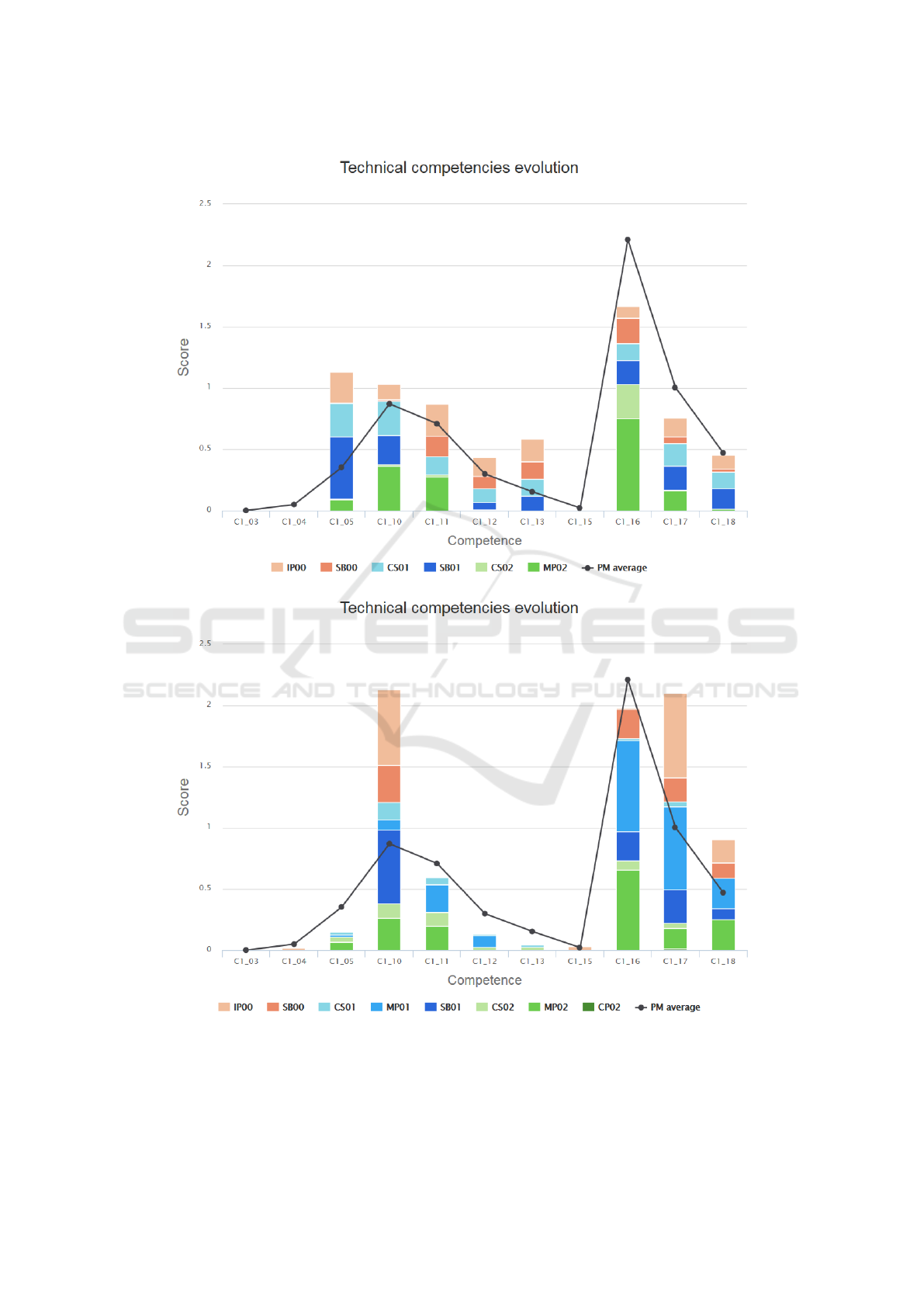

Figure 3 illustrates the individual scores evolution

for each assessed competence for two different

students that adopted the same role (Project Ma-

nager, PM). It is possible to observe, for exam-

ple, that the first student was involved in activities

that required the development of a wide variety

of competences, whereas the second student fo-

cused on specific activities and developed a smal-

ler number of competences. In this case, detailed

information was provided for each PRINCE2 pro-

cess (see Figure 1).

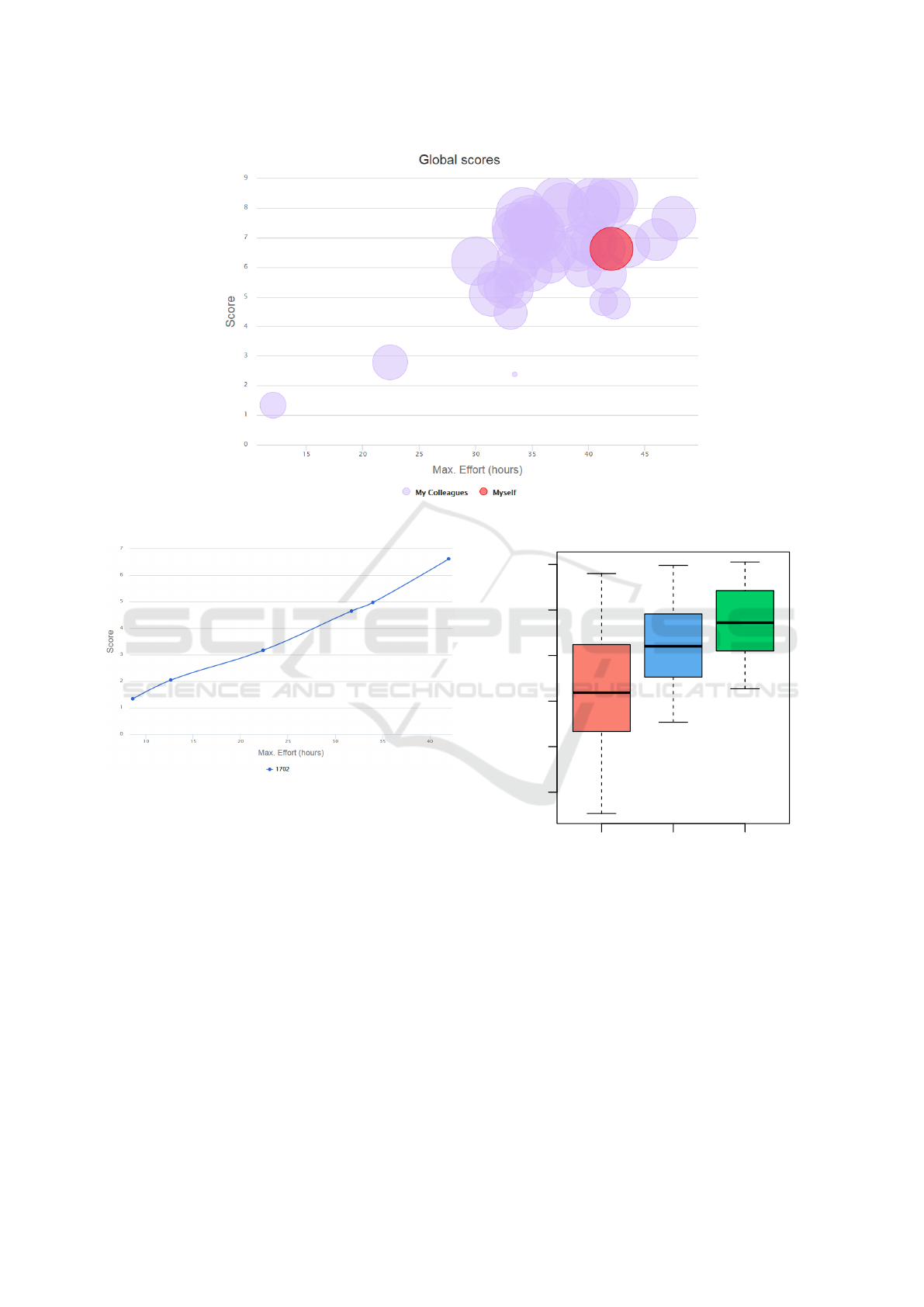

• In addition to competence assessment details, the

online system also provides a unique, numerical,

global score for each student. For example, Figure

4 shows the global score obtained by a student

(red circle) against the effort claimed by he or she.

The size of the circle is related to the efficiency of

the student, i.e., it indicates how well a student

was able to finish their assignments within the

adequate time. This plot also allows students to

anonymously compare their performance to that

of the other students.

• Finally, the system provides the learning curve

through project execution for each student. Fi-

gure 5 illustrates the learning curve for the same

student shown in Figure 4. In this case, detailed

information was also provided for each PRINCE2

process. This plot represents the increase (or de-

crease) of learning (global score) with experience

(claimed effort).

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of efficiency for each project

stage

Stage Mean SD

IS00 52.88 14.41

DS01 61.43 9.83

FS02 67.43 8.06

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this section we examine whether the proposed sy-

stem for assessment and feedback promote students

to improve their performance. Since the system pro-

vides information at least three times during the exe-

cution of a project, one per project life cycle phase

(or stage), the analysis of differences in students’ aca-

demic performance is performed at the end of each

executed stage (IS00, DS01 and FS02).

The participants in this study were 42 engineer-

ing students from the University of La Rioja (UR).

These engineering students were either undergradua-

tes in their fourth year (26 students) or first-year mas-

ters degree students (16 students) who were enrolled

in project management courses scheduled for the fall

semester.

Table 1 shows the descriptive information of effi-

ciency scores for each project stage. In this work, the

efficiency is defined as the ability to accomplish high

quality tasks (project products, management activi-

ties, etc.) within the adequate time and effort. These

results indicated an improvement in students perfor-

mance with every stage, i.e., after each assessment

and feedback.

The distribution of the efficiency scores of stu-

dents through the project execution is presented in

figure 6. Data analysis was carried out by means

of boxplots because they are a way of summarizing

a distribution. A boxplot (also known as a box and

whisker plot) is interpreted as follows:

• The box itself contains the middle 50% of the

data. The upper edge (hinge) of the box indicates

the 75th percentile of the data set, and the lower

hinge indicates the 25th percentile.

• The line in the box indicates the median value of

the data.

• The ends of the horizontal lines or whiskers indi-

cate the minimum and maximum data values.

• The points outside the ends of the whiskers are

outliers or suspected outliers.

Comparing the boxplots across groups, a simple

summary is to say that the box area for one group is

An Online Assessment and Feedback Approach in Project Management Learning

73

Figure 3: Examples of the technical competences evolution plot for two students with the same role (Project Manager, PM).

higher or lower than that for another group. To the ex-

tent that the boxes do not overlap, the groups are quite

different from one another. Figure 6 illustrates the

continuous and global improvement in students per-

formance with every stage. Since the feedback was

provided at the end of each project stage, these results

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

74

Figure 4: Example of the global scores screen for a student.

Figure 5: Example of the learning curve for a student.

suggest that the proposed combination of different ty-

pes of feedback has a positive impact on students’ per-

formance.

In order to determine the statistical difference

of the efficiency observed after each project stage,

i.e., after each assessment and feedback, the non-

parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed

because a normal distribution cannot be assumed. The

level of significance (alpha) was determined to be

0.05. As shown in table 1 and figure 6, the results

obtained for the students at the end of the second

stage (DS01) were superior to the ones obtained by

them at the end of the first stage (IS00). In the same

way, the results obtained by the students at the end of

the third stage (FS02) were also higher than the ones

obtained at the end of the second stage (DS01). All

the differences observed where significant in the cor-

●

IS00 DS01 FS02

30 40 50 60 70 80

Stage

Efficiency (%)

Figure 6: Evolution of students’ performance during the

course.

responding Wilcoxon signed-rank test (DS01-IS00, Z

= 7.37, p <0.001; FS02-DS01, Z = 8.15, p <0.001).

This fact, seems to corroborate the hypothesis that the

proposed assessment and feedback systems is useful

for the students to improve their performance in pro-

ject management.

In summary, tracking students performance by

means of the provided numerical and graphical infor-

mation enables each student to identify strengths and

weaknesses in his or her work. On the other hand, the

An Online Assessment and Feedback Approach in Project Management Learning

75

lessons learned reports, which identify what is consi-

dered as good and poor practices, provide advice on

how to proceed in the future. Thus, students have the

opportunity to close the gap between current and de-

sired performance on a stage per stage basis, at least.

Although caution must be taken and further rese-

arch should be conducted, it is worth mentioning that

informal conversations with students revealed that

comparison of each students’ performance with that

of their peers, which is possible by means of the pro-

vided plots, seems to play an important role in stu-

dents’ motivation.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has presented an online system for as-

sessment and feedback in learning project manage-

ment. The proposed system considers competence as-

sessment through a set of performance indicators that

are pertinent to each assessed competence. Informa-

tion, which is collected by means of specifically deve-

loped online forms, is not only sought from those who

produce a product or are responsible for its imple-

mentation (the learner), but also from the other main

actors in learning activities, i.e., the teachers and the

peers. Thus, all of the numerical data that have been

gathered are considered in a weighted integration to

yield a numerical assessment score of each compe-

tence that is developed for each student. On the other

hand, three different types of feedback are implemen-

ted and provided several times in order to promote and

improve students’ learning.

Data analysis from a specific academic course

suggest the proposed system has a positive impact on

students’ performance. Another interesting result is

the effect on students’ motivation that seems to have

the proposed feedback system.

Authors planned to conduct further research with

a greater number of students. Also, we consider it

necessary to carry out a deep quantitative analysis of

the collected data to better identify factors influencing

improvements in students’ performance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to recognise the financial support of

the University of La Rioja through grant EGI16/11.

REFERENCES

Andersson, C. and Palm, T. (2017). The impact of for-

mative assessment on student achievement: A study

of the effects of changes to classroom practice after a

comprehensive professional development programme.

Learning and Instruction, 49:92–102.

Andrade, H. and Du, Y. (2007). Student responses to

criteria-referenced self-assessment. Assessment and

Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(2):159–181.

Black, P. and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom

learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy

& Practice, 5(1)(1):7–74.

Black, P. and Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of

formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Eva-

luation and Accountability, 21(1):5–13.

Boud, D. (1995). Enhancing learning through self-

assessment. Kogan Page, London.

Brookhart, S. M., Moss, C. M., and Long, B. A. (2010). Te-

acher inquiry into formative assessment practices in

remedial reading classrooms. Assessment in Educa-

tion: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(1):41–58.

Caupin, G., Knoepfel, H., Koch, G., Pannenbcker, K.,

Perez-Polo, F., and Seabury, C. (2006). IPMA Com-

petence Baseline, version 3. International Project Ma-

nagement Association.

Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: Assessment is for

self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Re-

view, 24(2):205–249.

Falchikov, N. (2001). Learning Together. RoutledgeFalmer,

London.

Gibbs, G. and Simpson, C. (2004). Conditions under which

assessment supports students learning. Learning and

Teaching in Higher Education, 1:3 – 31.

Gielen, S., Peeters, E., Dochy, F., Onghena, P., and Struy-

ven, K. (2010). Improving the effectiveness of peer

feedback for learning. Learning and Instruction,

20(4):304–315.

Gikandi, J. W., Morrow, D., and Davis, N. E. (2011). Online

formative assessment in higher education: A review of

the literature. Computers and Education, 57(4):2333–

2351.

Gonz

´

alez-Marcos, A., Alba-El

´

ıas, F., Navaridas-Nalda, F.,

and Ordieres-Mer

´

e, J. (2016). Student evaluation of

a virtual experience for project management learning:

An empirical study for learning improvement. Com-

puters & Education, 102:172–187.

Gonz

´

alez-Marcos, A., Alba-El

´

ıas, F., and Ordieres-Mer

´

e, J.

(2015). An analytical method for measuring compe-

tence in project management. British Journal of Edu-

cational Technology, 47(6)(6):1324–1329.

Meusen-Beekman, K. D., Joosten-ten Brinke, D., and Bos-

huizen, H. P. A. (2016). Effects of formative asses-

sments to develop self-regulation among sixth grade

students: Results from a randomized controlled inter-

vention. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 51:126–

136.

Miller, C. M. L. and Parlett, M. R. (1974). Up to the Mark:

A Study of the Examination Game. Society for Rese-

arch into Higher Education.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

76

Nicol, D. J. and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative

assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and

seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in

Higher Education, 31(2):199–218.

Office Of Government Commerce (2009). Managing

Successful Projects with PRINCE2(

TM

). Office Of

Government Commerce.

Panadero, E., Alonso-Tapia, J., and Huertas, J. A. (2014).

Rubrics vs. self-assessment scripts: effects on first

year university students’ self-regulation and perfor-

mance. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 37(1):149–183.

Pintrich, P. R. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting

and sustaining self-regulated learning. International

Journal of Educational Research, 31(6):459 – 470.

Ross, J. (2006). The reliability, validity, and utility of self-

assessment. Practical Assessment, Research & Evalu-

ation, 11(10):1–13.

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on Formative Feedback. Source:

Review of Educational Research, 78228173(1):153–

189.

Snyder, B. R. (1971). The Hidden Curriculum. MIT Press,

MA.

Strudwick, R. and Day, J. (2015). Developing effective

assignment feedback for an interprofessional learning

module-An action research project. Nurse Education

Today, 35(9):974–980.

Ten

´

orio, T., Bittencourt, I. I., Isotani, S., and Silva, A. P.

(2016). Does peer assessment in on-line learning envi-

ronments work? a systematic review of the literature.

Computers in Human Behavior, 64:94–107.

Topping, K. (1998). Peer assessment between students in

colleges and universities. Review of Educational Re-

search, 68(3):249–276.

Tridane, M., Belaaouad, S., Benmokhtar, S., Gourja, B., and

Radid, M. (2015). The Impact of Formative Asses-

sment on the Learning Process and the Unreliability

of the Mark for the Summative Evaluation. Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197(February):680–

685.

van den Berg, I., Admiraal, W., and Pilot, A. (2006). Design

principles and outcomes of peer assessment in higher

education. Studies in Higher Education, 31(3):341–

356.

van Gennip, N. A., Segers, M. S., and Tillema, H. H. (2010).

Peer assessment as a collaborative learning activity:

The role of interpersonal variables and conceptions.

Learning and Instruction, 20(4):280–290. Unravel-

ling Peer Assessment.

van Zundert, M., Sluijsmans, D., and van Merrinboer, J.

(2010). Effective peer assessment processes: Rese-

arch findings and future directions. Learning and In-

struction, 20(4):270–279. Unravelling Peer Asses-

sment.

An Online Assessment and Feedback Approach in Project Management Learning

77