Motivational Factors that Influence the use of MOOCs:

Learners’ Perspectives

A Systematic Literature Review

Nada Hakami, Su White and Sepi Chakaveh

Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton, U.K.

Keywords: Learner’s Motivations, MOOC Acceptance, MOOC Adoption, MOOC Retention, MOOC Completion,

Learner’s Engagement, Literature Synthesis, MOOCs.

Abstract: Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have become an important environment for technology-enhanced

learning (TEL) where massive numbers of users from around the world access free, online-based, open

content generated by the world-class institutions. Understanding learner’s motivations for using MOOCs is

essential for providing successful MOOC environments. This paper presents a comprehensive picture of the

literature published between 2011-2016 and pertaining to the motivations that drive individuals to use

MOOCs as learners. We examined the classifications of papers, theories used, data collection methods,

motivational factors proposed and geographic distribution of participants. Findings demonstrate that the

related literature is limited. Several papers adopted technology acceptance theories. Quantitative survey was

the favoured method

for researchers. Key motivational factors were learner-related (which are divided into

personal, social and educational / professional development), institution and instructor-related, platform and

course-related and perception of external control/facilitating conditions-related. The identified studies

focused only on few geographic regions. Such findings are important for uncovering the directions in the

literature and determining the current gaps that can be addressed in the future.

1 INTRODUCTION

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) offer

people worldwide the chance to improve their

education free of charge with no commitment or

prior requirements. MOOCs are gaining wide-spread

attention and are rapidly changing the attitude

towards TEL. Since 2008, the number of higher

education institutions that provide MOOCs has

increased rapidly. It is reported that in 2015 there

were around 4,200 courses offered by 500

institutions while the total number of learners who

registered in MOOCs reached 35 million (Shah,

2015).

Barak et al. (2016, p.50) defined motivation as “a

reason or a goal a person has for behaving in a given

manner in a given situation”. In MOOCs, there is a

diversity in motivations among learners to use

MOOCs as a result of the open nature of MOOCs,

which allows anyone to participate (Kizilcec et al.,

2013; Bayeck, 2016). Investigating such motivations

offers insights for MOOCs providers into the

possible solutions for improving their services in

order to increase learners’ engagement, satisfaction,

completion rate, as well as meet their needs and

requirements.

There is a lack of systematic synthesis of

literature pertaining to factors motivating learners to

use MOOCs. The purpose of this paper is to present

a comprehensive and systematic review of the

literature related to this topic so as to highlight the

current research directions and gaps that can be

addressed in the future. To address the gaps in the

literature, we pose the following research questions

(RQ):

RQ1: What are related papers? How can the papers

be classified?

RQ2: What theoretical frameworks and reference

theories have been applied to study the topic?

RQ3: What data collection methods have been used

by related papers?

RQ4: What key motivational factors were proposed

in existing studies?

RQ5: What is the participants’ geographic

distribution in the related studies?

Hakami, N., White, S. and Chakaveh, S.

Motivational Factors that Influence the use of MOOCs: Learners’ Perspectives - A Systematic Literature Review.

DOI: 10.5220/0006259503230331

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 2, pages 323-331

ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

323

The reminder of this paper is structured as

follows: Section two highlights the related work.

Section three outlines the research method. Section

four describes the findings while section five

illustrates the discussion. Finally, conclusion is

presented in section six.

2 RELATED WORK

This section summarizes prior literature synthesis

that were focused on identifying the motivational

factors affecting learner’s intention to use MOOCs.

Only two literature synthesis pertaining to the

topic were found. Hew and Cheung (2014) aimed to

identify the learners’ and instructors’ motivations

and challenges of using MOOCs. They also

suggested future issues that need to be resolved. This

work is similar to our study. However, their study

was published in 2014 and many related studies

have emerged after this year. The goal of a study led

by Latha and Malarmathi (2016) is examining the

factors influencing the learners to complete MOOCs.

This study differs from ours in terms of that its focus

is only on MOOCs completion and not motivations

for using MOOCs.

We examined the literature based on different

research questions that are not addressed before. To

the best of our knowledge, this paper represents the

first effort to review the literature on motivations for

using MOOCs from learners’ viewpoints for a

particular time period (2011 to 2016) to make better

sense of various research trends and provide

proposal for further research.

3 METHODS

To accomplish our objective, we used the systematic

literature review strategy suggested by Kitchenham

(2004). The approach consists of five activities

which are: (A) Define research question, (B) Define

search keywords, (C) Select electronic resources,

(D) Search process, (E) Match inclusion and

exclusion criteria.

The search keywords used were “MOOCs

Learner Motivations”, “MOOCs Completion OR

MOOCs Retention”, and “MOOCs Learner

Engagement”. The papers were identified through

searching six educational technology journals and

six academic databases namely, British Journal of

Educational Technology, American Journal of

Distance Education, Distance Education, Open

Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-

Learning, European Journal of Open, Distance and

E-Learning, Computer Assisted Learning, Google

Scholar, IEEE Xplore, Elsevier’s ScienceDirect,

Wiley Online Library, SpringerLink and Scopus.

Tables 1,2 and 3 illustrate the ratio of search results

to relevant papers using the identified search

keywords. A number of search results from

journal/database are similar to other journal/database

results.

In order to be included in the corpus, each

identified paper ought to focus on the motivations

for using MOOCs from learner’s perspective. This

criterion was given the highest priority. However,

due to the limited number of related papers, further

criteria, with lower priority than the previous

criterion, were specified to choose appropriate

papers for inclusion in the review which are as

follows: the paper ought to focus either on (A) the

factors that influence the acceptance of MOOCs

(why people accept or reject the use of MOOCs) , or

(B) the learner’s motivations for MOOCs

completion / retention, or (C) the factors influencing

the success of MOOCs, or (D) addressing the

learners’ motivations for using MOOCs as a part of

other different objectives. We expect that these

additional papers might present factors that are

applicable to the motivations of using MOOCs.

Moreover, papers ought to be published between

January 2011 and October 2016 and written in

English. The reason of selecting year 2011 is that it

was the date when MOOCs have been used

extensively in online learning (Sunar et al., 2015).

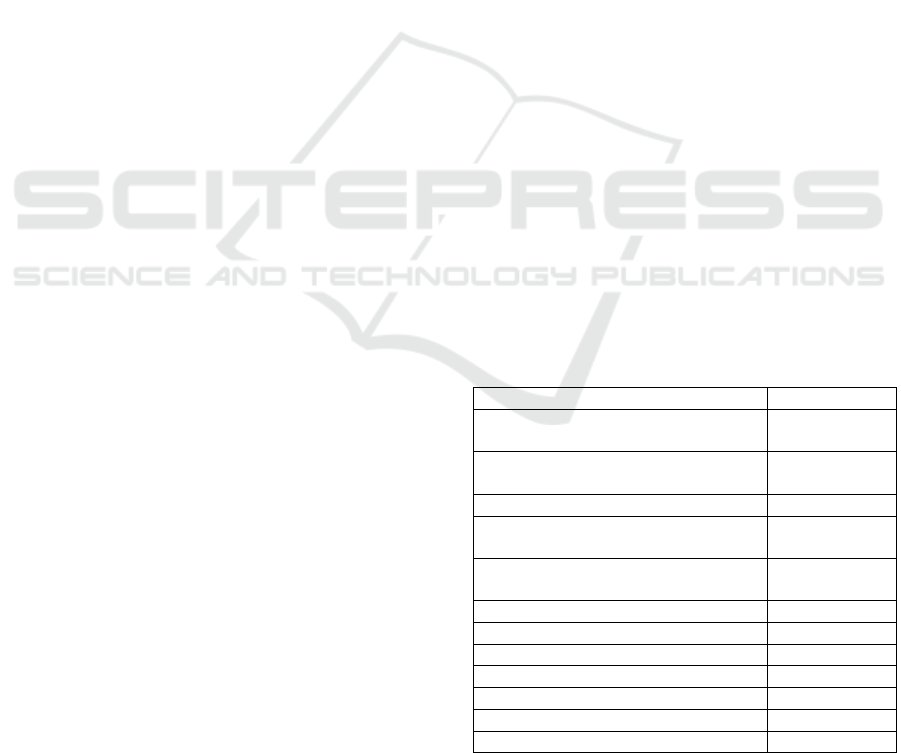

Table 1: The results of the search by the keyword

“MOOCs Learner Motivations”.

Journal /Data Base *SR:RP

British Journal of Educational

Technology

39:2

American Journal of Distance

Education

7:0

Distance Education 28:0

Open Learning: The Journal of Open,

Distance and e-Learning

23:0

European Journal of Open, Distance

and E-Learning

0:0

Computer Assisted Learning 9:0

Google Scholar 6,880:27

IEEE Xplore 247:0

Elsevier’s ScienceDirect 178:4

Wiley Online Library 125:3

SpringerLink 434:4

Scopus 259:14

*SR:RP Ratio of search results to relevant papers

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

324

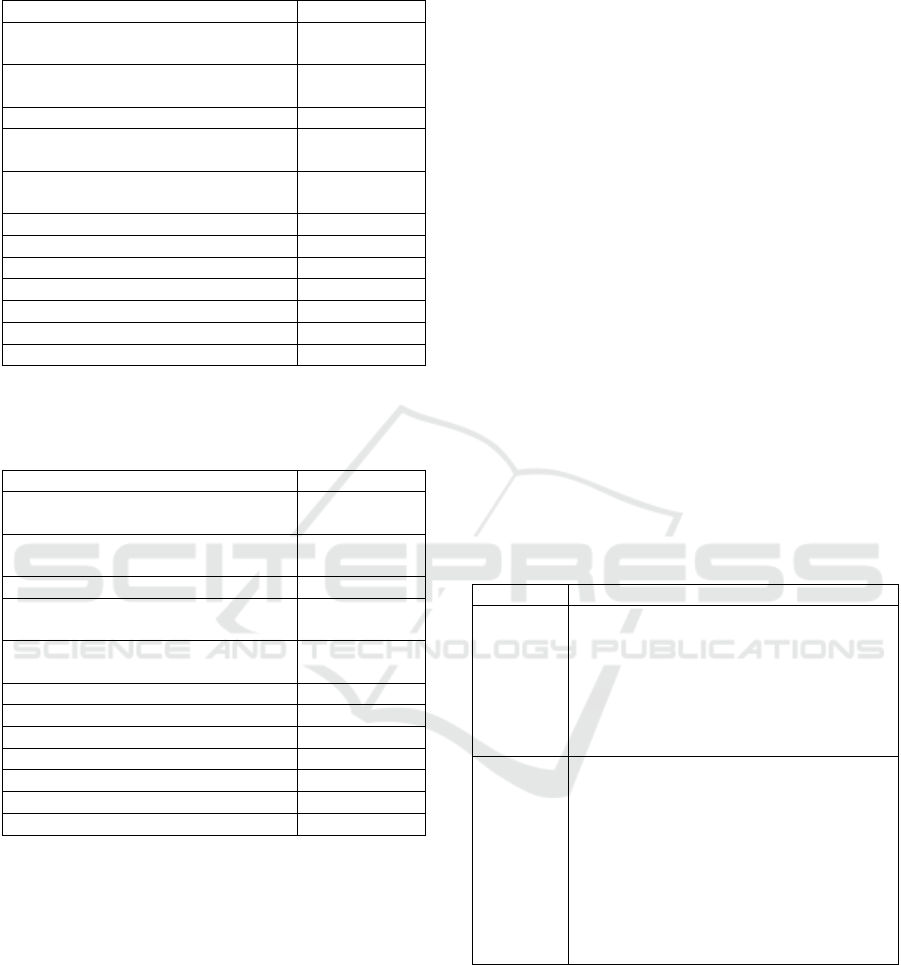

Table 2: The results of the search by the keyword

“MOOCs Completion OR MOOCs Retention”.

Journal /Data Base *SR:RP

British Journal of Educational

Technology

18:1

American Journal of Distance

Education

4:0

Distance Education 15:0

Open Learning: The Journal of Open,

Distance and e-Learning

16:0

European Journal of Open, Distance

and E-Learning

0:0

Computer Assisted Learning 7:0

Google Scholar 4,240:21

IEEE Xplore 304:0

Elsevier’s ScienceDirect 242:5

Wiley Online Library 183:2

SpringerLink 197:1

Scopus 35:5

*SR:RP Ratio of search results to relevant papers

Table 3: The results of the search by the keyword

“MOOCs Learner Engagement”.

Journal /Data Base *SR:RP

British Journal of Educational

Technology

29:1

American Journal of Distance

Education

9:0

Distance Education 37:0

Open Learning: The Journal of Open,

Distance and e-Learning

32:0

European Journal of Open, Distance

and E-Learning

0:0

Computer Assisted Learning 8:0

Google Scholar 9,800: 23

IEEE Xplore 199:0

Elsevier’s ScienceDirect 168:7

Wiley Online Library 143:3

SpringerLink 489:3

Scopus 32:1

*SR:RP Ratio of search results to relevant papers

In the data analysis phase, we used the constant-

comparative method suggested by Glaser (1965) to

classify the identified papers.

4 FINDINGS

This section presents the findings from the analysis

of the related studies as well as provides the answers

to our research questions.

4.1 What Are Related Papers? How

Can the Papers Be Classified?

The results of our analysis revealed that a total of

forty-two papers were related to the topic. It can be

observed that certain papers intended to develop a

model based on identifying explanatory variables

that are used to predict the use of MOOCs. In

contrast, other papers applied empirical methods

such as quantitative and qualitative data collection

methods in order to explore the learners’ motivations

behind enrolling on MOOCs without modelling the

motivational factors. Consequently, we clustered the

relevant papers into two main categories:

1. Modelling the motivational factors that

influence the use of MOOCs

2. Not modelling the motivational factors that

influence the use of MOOCs

The classification of the identified papers is shown

in Table 4. In this Table, all eleven identified papers

in the first category focused on modelling the factors

influencing learners’ intention to use MOOCs while

all seventeen identified papers of the second

category sought primarily to identify learners’

motivations for taking MOOCs.

Table 4: Classification of the identified papers.

Category Author(s) (year)

1

Xiong et al. (2014); Xu (2015); Chu et al.

(2015); Huanhuan and Xu (2015); Gao

and Yang (2015); Chaiyajit and

Jeerungsuwan (2015); Nordin et al.

(2015); Aharony and Bar-Ilan (2016);

Zhou (2016); Sa et al. (2016); Alraimi et

al. (2015)

2

Belanger and Thornton (2013);

Christensen et al (2013); Norman (2014);

Hew and Cheung (2014); Davis et al.

(2014); Gütl et al. (2014); Kizilcec and

Schneider (2015); Zheng et al. (2015); Liu

et al. (2015); Cupitt and Golshan (2015);

Li (2015); Salmon et al. (2016); Bayeck

(2016); Howarth et al. (2016); Uchidiuno

et al. (2016); Zhong et al. (2016); Garrido

et al. (2016)

We assigned additional three papers to the first

category. However, they established different

objectives from those of the previous papers in the

first category. Hone and El-Said (2016), Xiong et al.

(2015) and Adamopoulos (2013) aimed to develop a

model of the factors contributing to the MOOCs

completion and retention. The factors identified in

these papers can be tested in the context of the

intention to use MOOCs.

Motivational Factors that Influence the use of MOOCs: Learners’ Perspectives - A Systematic Literature Review

325

Further eleven papers, which have been assigned

to the second category, indirectly addressed the

motivations of learners for using MOOCs or

investigated the factors influencing learners’

retention or the success of MOOCs. Such papers are

as follows: Shrader et al. (2016), Chang et al.

(2015), Littlejohn et al. (2016), Rai and Chunrao

(2016), Gamage et al. (2015), Wang and Baker

(2015), Latha and Malarmathi (2016), Bakki et al.

(2015), Khalil and Ebner (2014), Greene et al.

(2015) and Barak et al. (2016).

4.2 What Theoretical Frameworks and

Reference Theories Have Been

Applied to Study the Topic?

Technology acceptance theories are the dominant in

the related publications in the first category. The

goal of these theories is to “specify a pathway of

technology acceptance from external variables to

beliefs, intentions, adoption and actual usage” (Van

Biljon and Kotzé, 2007, p.152). According to Louho

et al. (2006, p.15), “technology acceptance is mostly

about how people accept and adopt some technology

to use”. It was found that most of the studies

included into the first category group (11 papers)

used technology acceptance theories.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) has

emerged as the most popular theory with 6

publications employing it. Other used theories

included the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use

of Technology (UTAUT) (2 papers), TAM3(1

paper), Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) plus

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) which is one of

the leading motivation theories (1 paper) and

Information Systems Continuance Expectation

Confirmation (1 paper).

4.3 What Data Collection Methods

Have Been Used by Related

Papers?

Orlikowski and Baroudi (1991) classified research

into conceptual and empirical. Conceptual research

refers to studies that are based on formulating

concepts and models without using empirically

collected data. Literature review is an example of

this type of research. On the other hand, empirical

research refers to studies that are based on data

collection methods to generate and test hypotheses,

such as surveys, interviews, multi-method research,

case studies and experiments.

All previous studies falling under the first

category are empirical research. Survey quantitative

method has been used by all the related research

except for one research which is based on

observation, interview and analysing students’

textual reviews.

Researches falling under the second category are

classified into conceptual and empirical research.

Four publications are conceptual research using

literature review. With regards to empirical

quantitative studies, there is a large volume of

published studies using the survey method (13

papers) with one publication that applied survey and

activity data analysis methods. Empirical qualitative

studies utilized the interview (1 paper), literature

review and observation (1 paper), and observation

and interview (1 paper). Studies based on mixed-

methods approach used survey and interview (3

papers); survey, clickstream and event data analysis

(1 paper); survey and forum posts and email

messages analysis (1 paper). The data collection

method used in the study by Rai and Chunrao (2016)

was based on general opinions that were derived

from the perspectives of MOOCs learners but was

not clearly identified in the paper. Overall, it turned

out that the quantitative approach based on a survey

method was the most frequently applied research

strategy in both categories, with 26 papers (61.90%).

4.4 What Key Motivational Factors

Were Proposed in Existing Studies?

We identified forty-three motivational factors

reported in the related publications. Having

identified the proposed motivational factors that

drive individuals to the use of MOOCs, we classified

those factors into four main dimensions: learner-

related factors, institution and instructor-related

factors, platform and course-related factors, and

perception of external control/ facilitating

conditions-related factors. The factors identified

under each main dimension can be listed as follows:

1. Learner-related factors

This dimension includes the factors related to

the learners themselves. The factors are divided

as following:

1.1. Personal factors: including curiosity,

perceived enjoyment, learner’s attitude,

computer playfulness, computer anxiety,

satisfaction, extrinsic motivation, intrinsic

motivation, challenge, human capital (being

able to behave in new ways) and awareness.

1.2. Social factors: including subjective norm

(social influence), interaction with learners,

image (social status) and mimetic pressure.

1.3. Educational/Professional development

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

326

factors: including job/academic relevance,

extend knowledge and skills, earn a

certificate, get learning opportunities not

otherwise available, prepare for future,

improve English ability and special project

requirements.

2. Institution and instructor-related factors

This dimension consists of two factors related to

the characteristics of institutions and instructors

namely, perceived reputation and interaction

with instructor.

3. Platform and course-related factors

This dimension includes the factors that

describe the characteristics of the platforms and

courses. Such factors include: perceived

usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived

openness (open access to MOOCs without

restrictions), course’s content quality, course

characteristics (such as the course’s discipline

and the duration of a course), ubiquity

(flexibility or convenience), perceived

utilitarian value (tradeoff between received and

given things), objective usability, output quality,

trust, perceived effectiveness, MOOC

popularity, information richness (the amount of

details used to convey the information),

personalization and gamification.

4. Perception of external control/Facilitating

conditions

The perception of external control/facilitating

conditions is defined as “the degree to which an

individual believes that organizational and

technical resources exist to support the use of

the system” (Venkatesh and Bala, 2008, p.279).

This dimension encompasses learner’s skills

and technology-related factors.

4.1. Learner’s skill-related factors: including

computer self-efficacy, experience in

MOOCs and self-determination (self-

regulated learning).

4.2. Technology-related factors: including

technology compatibility.

One obvious finding to emerge from the analysis

is that the most frequently proposed factors in the

studies in the first category were: perceived

usefulness (10 papers), perceived ease of use (10

papers), and perception of external control/

facilitating conditions (4 papers). In the studies

assigned to the second category, the most frequently

suggested factors were: extend knowledge and skills

(25 papers), curiosity and earn a certificate (16

papers) and interaction with learners (14 papers).

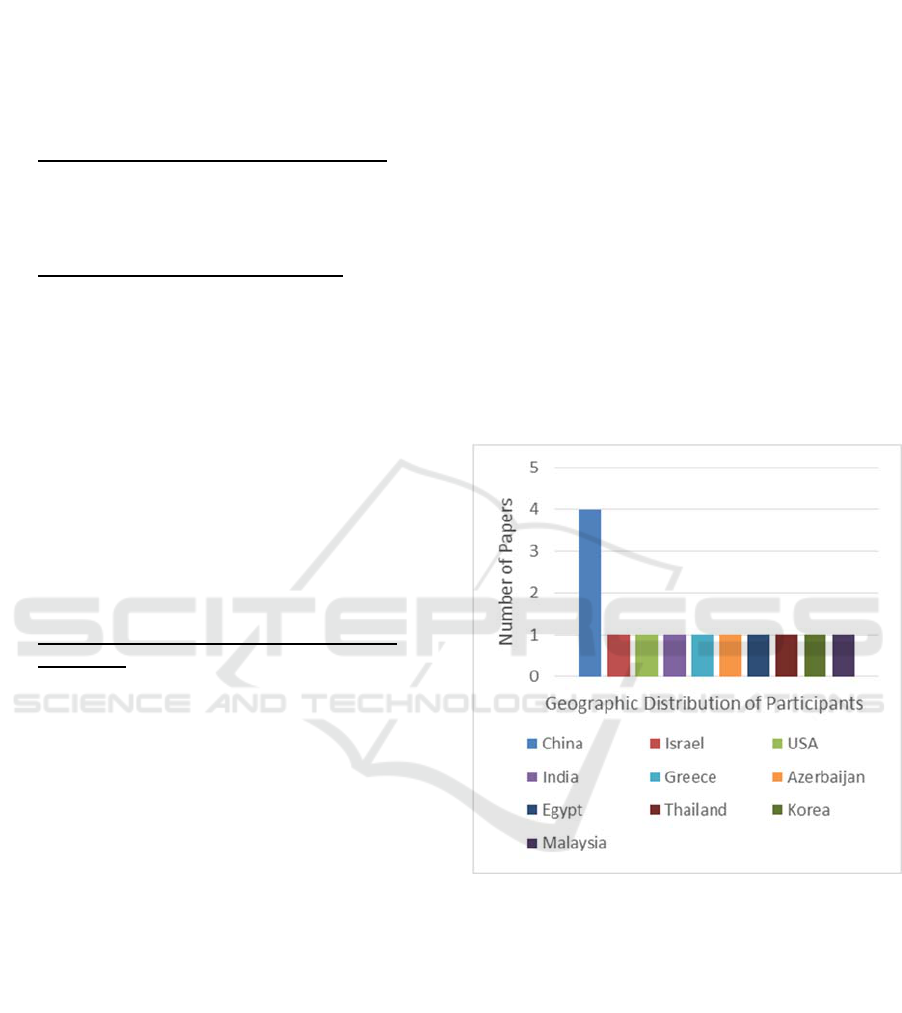

4.5 What Is the Participants’

Geographic Distribution in the

Related Studies?

Participants in the related studies are the users who

have been selected during the data collection stage

for reporting their motivations for using MOOCs.

The results obtained from the analysis shows that 10

papers in the first category reported the participants’

geographic distribution. All these studies examined

the perspectives of users from specific countries

except for one study by Alraimi et al. (2015) which

employed users from different countries. As can be

seen from Figure 1, most of these studies focused on

exploring the factors driving users from China to use

MOOCs (4 papers). Other reported countries were:

Israel, USA, India, Greece, Azerbaijan, Egypt,

Thailand, Korea and Malaysia.

Figure 1: Geographic distribution of participants in the

studies in the first category.

On the other hand, 13 papers assigned to the second

category stated the geographic distribution of the

participants. Conversely, these publications did not

focus on the perspectives of users from a specific

country or culture. Each of these studies employed

participants originating from different countries. As

Figure 2 shows, the most frequently mentioned

countries were the USA (7 papers), India (7 papers),

Spain (6 papers), and then four papers for each of

the following countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada,

China, and Germany.

Motivational Factors that Influence the use of MOOCs: Learners’ Perspectives - A Systematic Literature Review

327

Figure 2: Geographic distribution of participants in the

studies in the second category.

5 DISCUSSION

Our analysis of forty-two related papers revealed

important findings. One interesting finding is that

the amount of research on MOOCs acceptance and

the factors influencing their use is limited.

Moreover, only few papers adopt the technology

acceptance theories.

Another important finding was that 61.90% of

papers used solely a survey as a method for data

collection. The finding of this study also shows that

the main factors driving learners to MOOCs

enrolment were learner-related (divided into

personal, social and educational / professional

development), institution and instructor-related,

platform and course-related and perception of

external control/facilitating conditions-related.

Unlike the studies assigned to the first category,

most of the studies from the second category did not

examine the motivations of users from specific

countries or cultures. With regards to the geographic

distribution of participants in related studies falling

under the first category, the most frequently

mentioned country was China whereas in the studies

in the second category the main focus was on the

USA, India, Spain, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China,

and Germany.

These findings help us to understand current

research directions in the motivations for using

MOOCs from learners’ perceptions, identify

research gaps and provide suggestions for further

research. Based on our findings, it can be concluded

that substantial efforts are needed to investigate the

topic from different perspectives and angles. There

are numerous motivation and technology acceptance

theories which have been tested in various contexts.

Testing the applicability of these theories within the

context of MOOCs is a rich area for future research.

Because technology acceptance model (TAM) was

built from a quantitative survey study, it is not

surprising that survey quantitative methodology is

the only method used by the papers that adopted

technology acceptance theories. Likewise, most

papers of the second category also used the survey

method. One recommended method for future

research is applying mixed-methods. The reason for

mixing both quantitative and qualitative data within

one study is that neither quantitative nor qualitative

methods are adequate to understand the problem and

the details of a situation, hence integrating both

methods can complement each other (Ivankova et

al., 2006).

Related studies addressed many motivational

factors leading to the usage of MOOCs.

Nevertheless, there is abundant room for further

progress in determining other influential factors

affecting MOOCs use. For example, further study

may be undertaken to investigate the influence of

intercultural exchange within MOOCs on the

MOOC acceptance. In addition, a further study with

more focus on understanding the influence of self-

regulated learning capabilities on the learner’s

intention to use MOOCs is also

suggested. Investigating the influence of earning

certificate of course completion on MOOC

acceptance is also useful research.

The related literature concentrated on the

perspectives of users from few geographic regions.

Christensen et al. (2013) reported that the reasons

for enrolling in MOOC courses varied by country.

Similarly, Davis et al. (2014) found that learners’

motivations to participate in MOOCs can vary

significantly across cultures. No published studies

have been conducted so far to determine the

motivations of Arabic individuals to accept MOOCs

except for two papers by Davis et al. (2014) and

Hone and El-Said (2016) which examined the

viewpoints of Syrian and Egyptian individuals

respectively. In light of these findings, in future

investigations, it might be useful to identify the

motivational factors influencing users from different

countries and cultures such as Arabic or developing

countries. In general, in order to develop a full

picture of MOOCs acceptance, additional studies

will be needed.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

328

6 CONCLUSIONS

Prior literature that focused on the learners’

motivations to use MOOCs have been examined.

We reported the classifications of papers, theories

used, data collection methods, motivational factors

proposed and geographic distribution of participants.

This systematic analysis enables researchers to

understand the related literature on motivations for

using MOOCs from learners’ viewpoints and its

directions and limitations.

Based on our findings, there are many

suggestions for future research. First, it would be

interesting to investigate the motivations of learners

from Arabic countries to accept MOOCs and

compare the findings with motivations of learners

from other countries. Second, it is suggested that the

correlation between learners’ motivations and course

completion is investigated in future studies. Third, a

further study could validate the technology

acceptance and motivation theories within the

context of MOOCs. Finally, further investigation

into influence of self-regulated learning capabilities

on the learners’ intention to accept MOOCs is

recommended. We expect that this research will

serve as a base for future studies.

REFERENCES

Adamopoulos, P., 2013. What makes a great MOOC? An

interdisciplinary analysis of online course student

retention. In Proceedings of the 34th international

conference on information systems, ICIS, Milan.

Aharony, N. and Bar-Ilan, J., 2016. Students’ perceptions

on MOOCs: An exploratory study. Interdisciplinary

Journal of e-Skills and Life Long Learning, 12,

pp.145-162.

Alraimi, K. M., Zo, H. and Ciganek, A. P., 2015.

Understanding the MOOCs continuance: The role of

openness and reputation. Computers & Education,80,

pp. 28-38.

Bakki, A., Oubahssi, L., Cherkaoui, C. and George, S.,

2015. Motivation and Engagement in MOOCs: How

to Increase Learning Motivation by Adapting

Pedagogical Scenarios?. In Design for Teaching and

Learning in a Networked World, pp. 556-559.

Springer International Publishing.

Barak, M., Watted, A. and Haick, H., 2016. Motivation to

learn in massive open online courses: Examining

aspects of language and social engagement.

Computers & Education, 94, pp. 49-60.

Bayeck, R.Y., 2016. Exploratory study of MOOC

learners’ demographics and motivation: The case of

students involved in groups. Open Praxis, 8(3), pp.

223-233.

Belanger, Y. and Thornton, J., 2013. Bioelectricity: A

quantitative approach Duke University’s first MOOC.

Chaiyajit, A. and Jeerungsuwan, N., 2015. A Study of

Acceptance of Teaching and Learning toward Massive

Open Online Course (MOOC). In The Twelfth

International Conference on eLearning for

Knowledge-Based Society.

Chang, R. I., Hung, Y. H. and Lin, C. F., 2015. Survey of

learning experiences and influence of learning style

preferences on user intentions regarding MOOCs.

British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), pp.

528-541.

Christensen, G. et al., 2013. The MOOC Phenomenon:

Who Takes Massive Open Online Courses and Why?

University of Pennsylvania, nd Web, 6, pp. 1-14.

Chu, R., Ma, E., Feng, Y. and Lai, I.K., 2015, July.

Understanding Learners’ Intension Toward Massive

Open Online Courses. In International Conference on

Hybrid Learning and Continuing Education, pp. 302-

312. Springer International Publishing.

Cupitt, C. and Golshan, N., 2015. Participation in higher

education online: Demographics, motivators, and grit.

Davis H., Dickens K., Leon M., Sánchez-Vera M. and

White S. ,2014. MOOCs for Universities and

Learners- An Analysis of Motivating Factors. In

Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on

Computer Supported Education, pp. 105-116.

Gamage, D., Fernando, S. and Perera, I., 2015, August.

Factors leading to an effective MOOC from

participiants perspective. In Ubi-Media Computing

(UMEDIA), 2015 8th International Conference, pp.

230-235. IEEE.

Gao, S. and Yang, Y., 2015. Exploring Users’ Adoption of

MOOCs from the Perspective of the Institutional

theory. In the Fourteen Wuhan Intonational

Conference on E-Business Human Behavior and

Social Impacts on E-Business, pp. 383-390.

Garrido, M., Koepke, L., Anderson, S., Felipe Mena, A.,

Macapagal, M. and Dalvit, L., 2016. The Advancing

MOOCs for Development Initiative: An examination

of MOOC usage for professional workforce

development outcomes in Colombia, the Philippines,

& South Africa. Technology & Social Change Group.

Glaser, B.G., 1965. The constant comparative method of

qualitative analysis. Social problems, 12(4), pp. 436-

445.

Greene, J. A., Oswald, C. A. and Pomerantz, J., 2015.

Predictors of retention and achievement in a massive

open online course. American Educational Research

Journal, 52(5), pp. 925-955.

Gütl, C., Rizzardini, R. H., Chang, V. and Morales, M.,

2014. Attrition in MOOC: Lessons learned from drop-

out students. In Learning Technology for Education in

Cloud. MOOC and Big Data, pp. 37-48. Springer

International Publishing.

Hew, K. F. and Cheung, W.S., 2014. Students’ and

instructors’ use of massive open online courses

(MOOCs): Motivations and challenges. Educational

Research Review, 12, pp. 45-58.

Motivational Factors that Influence the use of MOOCs: Learners’ Perspectives - A Systematic Literature Review

329

Hone, K. S. and El Said, G. R., 2016. Exploring the

factors affecting MOOC retention: A survey study.

Computers & Education, 98, pp. 157-168.

Howarth, J.P., D’Alessandro, S., Johnson, L. and White,

L., 2016. Learner motivation for MOOC registration

and the role of MOOCs as a university ‘taster’.

International Journal of Lifelong Education, pp. 1-12.

Huanhuan, W. and Xu, L., 2015, September. Research on

technology adoption and promotion strategy of

MOOC. In Software Engineering and Service Science

(ICSESS), 2015 6th IEEE International Conference,

pp. 907-910. IEEE.

Ivankova, n. V., creswell, j. W., and stick, s. L. (2006).

Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design:

from theory to practice. Field methods, 18(1), pp. 3-

20.

Khalil, H. and Ebner, M., 2014, February. MOOCs

completion rates and possible methods to improve

retention-A literature review. In World Conference on

Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and

Telecommunications, 1, pp. 1305-1313.

Kitchenham, B., 2004. Procedures for performing

systematic reviews. Keele, UK, Keele University,

33(2004), pp. 1-26.

Kizilcec, R.F., Piech, C. and Schneider, E., 2013, April.

Deconstructing disengagement: analyzing learner

subpopulations in massive open online courses. In

Proceedings of the third international conference on

learning analytics and knowledge, pp. 170-179. ACM.

Kizilcec, R. F. and Schneider, E., 2015. Motivation as a

lens to understand online learners: Toward data-driven

design with the OLEI scale. ACM Transactions on

Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 22(2), p.6.

Latha, A. and Malarmathi, K., 2016. Factors Influencing

Successful Completion of Massive Open Online

Courses: A Synthesis of Literature. Global Journal

For Research Analysis, 5(1), pp. 66-68.

Li, K., 2015. Motivating Learners in Massive Open Online

Courses: A Design-based Research Approach

(Doctoral dissertation, Ohio University).

Littlejohn, A., Hood, N., Milligan, C. and Mustain, P.,

2016. Learning in MOOCs: Motivations and self-

regulated learning in MOOCs. The Internet and

Higher Education, 29, pp. 40-48.

Liu, M., Kang, J. and McKelroy, E., 2015. Examining

learners’ perspective of taking a MOOC: reasons,

excitement, and perception of usefulness. Educational

Media International, 52(2), pp. 129-146.

Louho, R., Kallioja, M. and Oittinen, P., 2006. Factors

affecting the use of hybrid media applications.

Graphic arts in Finland, 35(3), pp. 11-21.

Nordin, N., Norman, H. and Embi, M.A., 2015.

Technology Acceptance of Massive Open Online

Courses in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Distance

Education, 17(2), pp. 1-16.

Norman, A., 2014. The who, why and what of MOOCs. In

Proceedings ascilite Dunedin, pp. 717-721.

Orlikowski, W.J. and Baroudi, J.J., 1991. Studying

information technology in organizations: Research

approaches and assumptions. Information systems

research, 2(1), pp. 1-28.

Rai, L. and Chunrao, D., 2016. Influencing factors of

success and failure in MOOC and general analysis of

learner behavior. International Journal of Information

and Education Technology, 6(4), pp. 262-268.

Sa, J. H., Lee, J. M., Kang, T.W., Gim, G. Y. and Kim,

J.B., 2016. A Study of Factors Affecting the Intention

of Usage in MOOC. In Advanced Science and

Technology Letters, pp. 160-163.

Salmon, G., Pechenkina, E., Chase, A. M. and Ross, B.,

2016. Designing Massive Open Online Courses to take

account of participant motivations and expectations.

British Journal of Educational Technology.

Shah, D., 2015. By the numbers: MOOCS in 2015 - class

central’s MOOC report. Available at:

https://www.class-central.com/report/moocs-2015-

stats/ (Accessed: 16 June 2016).

Shrader, S., Wu, M., Owens-Nicholson, D. and Santa Ana,

K., 2016. Massive open online courses (MOOCs):

Participant activity, demographics, and satisfaction.

Online Learning, 20(2).

Sunar, A. S., Abdullah, N. A., White, S. and Davis, H.,

2015, May. Personalisation in MOOCs: A Critical

Literature Review. In International Conference on

Computer Supported Education, pp. 152-168. Springer

International Publishing.

Uchidiuno, J., Ogan, A., Yarzebinski, E. and Hammer, J.,

2016, April. Understanding ESL Students' Motivations

to Increase MOOC Accessibility. In Proceedings of

the Third (2016) ACM Conference on Learning@

Scale, pp. 169-172. ACM.

Van Biljon, J. and Kotzé, P., 2007, October. Modelling the

factors that influence mobile phone adoption. In

Proceedings of the 2007 annual research conference

of the South African institute of computer scientists

and information technologists on IT research in

developing countries, pp. 152-161. ACM.

Venkatesh, V. and Bala, H., 2008. Technology acceptance

model 3 and a research agenda on interventions.

Decision sciences, 39(2), pp. 273-315.

Wang, Y. and Baker, R., 2015. Content or platform: Why

do students complete MOOCs?. Journal of Online

Learning and Teaching, 11(1), pp.17-30.

Xiong, J., Tripathi, A., Nguyen, C. and Najjar, L., 2014.

Information and Communication Technology for

Development: Evidence from MOOCs Adoption. In

Proceedings of the Ninth Midwest Association for

Information Systems Conference.

Xiong, Y., Li, H., Kornhaber, M. L., Suen, H. K., Pursel,

B. and Goins, D. D., 2015. Examining the Relations

among Student Motivation, Engagement, and

Retention in a MOOC: A Structural Equation

Modeling Approach. Global Education Review, 2(3).

Xu, F., 2015. Research of the MOOC study behavior

influencing factors. In Proceedings of international

conference on advanced information and

communication technology for education, Atlantis

Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp. 18-22.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

330

Zheng, S., Rosson, M. B., Shih, P. C. and Carroll, J. M.,

2015, February. Understanding student motivation,

behaviors and perceptions in MOOCs. In Proceedings

of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported

Cooperative Work & Social Computing, pp. 1882-

1895. ACM.

Zhong, S. H., Zhang, Q.B., Li, Z. P. and Liu, Y., 2016.

Motivations and Challenges in MOOCs with Eastern

Insights. International Journal of Information and

Education Technology, 6(12), p.954.

Zhou, M., 2016. Chinese university students' acceptance

of MOOCs: A self-determination perspective.

Computers & Education, 92, pp.194-203.

Motivational Factors that Influence the use of MOOCs: Learners’ Perspectives - A Systematic Literature Review

331