“Objectivity” and “Situativity” in Knowledge It Artifacts

Incommensurable but Sensible Dimensions in Different Contexts

Carla Simone

DISCo, University of Milano Bicocca, Viale Sarca 336, 20126 Milano, Italy

Keywords: Knowledge Artifact, Under-specification, Bounded Openness, Learning, Knowledge Management,

Community of Practice.

Abstract: The main claim of the paper is that in order to design Knowledge IT Artifacts it is necessary to uncover the

Knowledge Artifacts that are currently in use (situativity) and to make the related technology respect the

practices around them. The alternative dimension (objectivity) can be leveraged when such KA are not

recognizable but in this case the tools characterizing this dimension can be used but with different purposes.

This claim is based on a series of empirical studies in real settings that show how the local conditions play a

fundamental role in the identification of the requirements of a technology supporting learning and problem

solving.

1 INTRODUCTION

Following the framework proposed in (Cabitza and

Locoro, 2014) as a results of a survey on the concept

of Knowledge Artifact (KA), we adopt the two

dimensions, namely “objectivity” (i.e. “the capability

of a KA to represent true facts in an objective, crisp,

and context-independent manner, as well as the extent

it can be transferred among its users as an object

carrying some knowledge with itself”), and

“situativity” (i.e., “the extent the KA is capable to

adapt itself to the context and situation at hand, as

well as of the extent it can be appropriated by its

users and exploited in a given situation”), to articulate

our reflection on the concept of KA and its possible

computational counterpart (KITA).

The choice to consider both KA and KITA

separately is based on the need to avoid any undue

contamination between reflections on an artefact that

can exists in a not digitalized form and those on its

possible translation in a piece of technology.

We like to start from a question that shows an

example of the potential contamination we mentioned

above: Can objectivity and situativity be seen as

dimensions which can be present at different degrees

in each KITA? While a KITA, interpreted as those

specific IT artifacts, i.e., applications and software

platforms, that specifically support knowledge

creation and sharing, might contain objective and

situated (to put it shortly) components that can

suitably be present in a comprehensive technology

affording a unique interaction point, a KA as a logical

construct (possibly reified in a not computational

support) can hardly encompass both dimensions: in

our opinion they are fundamentally incommensurable

but more importantly potentially risky to be mixed

without a focused reflection. Unless specified, we

will use the acronym KA to refer to a web of artifacts

(Bardram and Bossen, 2005) that are somehow

interdependent and can be seen as a unique logical

construct.

2 KNOWLEDGE AND

KNOWLEDGE ARTIFACTS

To support our claim it is worth clarifying what we

consider as a KA (as there are many contradictory

definitions of this term) before considering its

possible computational counterpart. Our position is as

follows. First, knowledge belongs to the individuals

and cannot be separated form them: it is not and

cannot be transformed in an object out there;

moreover knowledge has an irreducible social nature

since it is the outcome of a social construction

(McDermott, 1999; Berger and Luckmann 1967).

Then, what is not constructed in this way cannot be

considered as knowledge and then be related to the

theme of learning (or to use a buzzword, of

Simone, C..

“Objectivity” and “Situativity” in Knowledge It Artifacts - Incommensurable but Sensible Dimensions in Different Contexts.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 415-420

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

415

Knowledge Management (KM)): what is often, after

(Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995), called explicit

knowledge is nothing else than a representation that

can be shared only as mutually accessible information

(Blackler, 1995; Kakihara and Soerensen, 2002).

On the basis of this premise and in order to make

our argumentation coherent, it is necessary to

characterize what a KA is since this term has been

defined in contradictory ways as aptly discussed in

(Cabitza and Locoro, 2014). Moreover, and in

accordance with the above premise, this

characterization should be rooted in the practices of

knowledgeable professionals. On the basis of a

number of empirical studies, (Cabitza et al., 2013)

discussed the nuanced facets that characterize a KA

“in action” and proposed the following definition that

we will adopt in our argumentation: a KA is a

physical, i.e., material but not necessarily tangible,

inscribed artifact that is collaboratively created,

maintained and used to support knowledge-oriented

social processes (among which knowledge creation

and exploitation, collaborative problem solving and

decision making) within or across cooperative

settings and to support their actions according to its

negotiated structure, contingent content and

interpreted affordances; moreover, the representation

language and the representations shared in such a KA

allow for an affordable, continuous and user driven

maintenance and evolution of both its structure and

content at the appropriate level of underspecification.

The first implication is that it is not sufficient for

an artifact to contain some pieces of information that

can be related in some way to the (social)

construction of a professional knowledge to be a KA.

Second, between the two dimensions, situativiy is the

one that fits the above definition of a KA; objectivity

instead is incompatible with this characterization.

The next implication is that to recognize an

artifact as a KA it has to be considered from a

perspective that considers in an integrated way what

it contains and the process that lets the KA survive in

the collaborative setting where it plays its role. In

accordance with the above characterization of a KA

this setting can be naturally related to the notion of

CoP (Wenger, 1998) as the effectiveness of a KA is

based on a continuous “negotiation of meanings” of

its contents: indeed, a KA is a typical part of the

“common repertoire” that supports the joint action of

the community members; its usefulness and survival

in the community depend on the “joint enterprise”

and “mutual commitment” that bind the community

members. In (Cabitza et al., 2013) examples can be

found of CoPs and of the KA they have constructed

to support their practices in domains such as the

design of technical products and the hospital care: we

will refer to them in a following section.

We note in passing that uncovering “true” CoP is

not easy as they often are hidden (purposely or

unaware) from the more evident and explicit

organization and its operational rules. Too often this

notion has been misused by calling any group of

professionals a CoP and then by misinterpreting their

very nature and drawing undue implications on the

supportive technology. In this respect, looking for a

KA can be a fruitful way to uncover them, as it is a

symptom of a candidate CoP where collaborative

learning is at the basis of the common practices.

Moreover, according to the situative approach we

claim that CoPs cannot be built but are truly emergent

structures that can be at most facilitated by favourable

individual and organizational conditions (De

Michelis, 2012).

To sum up, the two dimensions of situativity and

objectivity are incommensurable when knowledge is

concerned; consequently, this holds for all the other

notions that refer to knowledge in their definition.

Then the question is if there is room for the

objectivity dimension and under which conditions.

Before answering this question, we consider the

features of a KITA that translates a KA in a

corresponding technology.

3 GENERAL FEATURES OF A

KITA

Which are then the characteristics of a KITA

supporting the life of a KA within a CoP? primarily,

the full respect of the nature of its contents and of the

practices around it. This means coping with under-

specification and bounded openness, avoiding

exogenous models and structures, avoiding undue

“optimization” of the way in which a KA is

constructed and maintained: in a word, respect the

actual users and their practices. These are the

outcome of a negotiation process whose effectiveness

cannot be overtaken by any external technological

and/or organizational intervention. The designer of

the technology has to take a humble position and

avoid any autonomous interpretation of the given

reality. She has to construct a “light” KITA in

relation to the typical knowledge management

technologies (ontologies, inference rules,

sophisticated and exhaustive knowledge

representations and related manipulation algorithms);

but at the same time deal with a demanding

conceptualization of a KITA to seriously respect the

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

416

practices of the target CoP (how to support under-

specification in an effective way? how to make the

KITA flexible enough to support its co-evolution

with the related CoP?). The KA actually in use should

be a precious and fundamental source of inspiration

for such design.

4 RELATING KA AND KITA

We are now in the position to consider the

relationship between KA and KITA by illustrating

some examples of how the definition of a KA can be

instantiated in a real context and how a corresponding

technology can be conceived.

The empirical work has shown that different kinds

of documental KA. The first kind encompasses

artifacts that include self-contained representations.

Examples of this kind of KA are the schema that the

designers of technical products mentioned above have

collaboratively constructed to support their problem

solving and re-use of previous solutions. We refer to

(Cabitza et al., 2013) for a detailed description; here

is sufficient to recall the main tenets underpinning the

adopted schemas. Irrespective of the complexity of

the related domains (software production and the

definition of the composition of the rubber

component of a tire, respectively) the designer

defined very concise (that is highly underspecified)

schemas and used them to discuss new products and

to leverage the experience gained in the construction

of past solutions. These schemas are made of a very

limited number of basic concepts (kinds of software

components in one case and ingredients and

performances in the other case) and of a limited kind

of relations connecting them: for example the kind of

dependency among software components or the

degree of correlation between the amount of an

ingredient in the compound and a specific

performance (typically, grip, duration, cost and the

like). These highly qualitative and symbolically

represented relations were able to evoke in the mind

of these professionals the specific knowledge to put

to work to transform them in fully specified quantities

and solutions. In the case of the design of the

chemical compound the formalization of this kind of

knowledge in a knowledge base was considered

almost useless during the creative phase and was

instead appreciated as a sandbox for the purpose of

training newcomers. For the designers, the used and

useful part of the whole application, that is their

KITA, was a light support to share the schemas

recording the choices made during each design effort.

Another example of self-contained KA is the

Daily Work Sheet (called “report” in (Munkvold et

al., 2007)), an unofficial document where nurses

write information (clinical data, examination requests

and remarks/observations) that is used by the nurses

of the next shift for sake of coordination (which

relevant actions have to be done for critical patients)

but more importantly contextual information that

helps the incoming nurses to interpret the clinical

situation they have to manage. These notes are

textual, with conventional terms and symbols that

make them sufficiently concise and informative. Here

the KITA requested by the nurses was a collaborative

editing tool that should allow the flexible use of

conventional symbols and text structure.

The second kind of KA encompasses artifacts that

integrate existing information structures: the latter are

typically imposed from the top through various kinds

of Information Systems (IS). An example are the

various forms of annotation that are widely used in

the architectural design (Schmidt and Wagner, 2004)

to express hypothetical solutions and links to other

documents produced by a CAD system (Figure1).

Figure 1: Plan of a floor and its annotations.

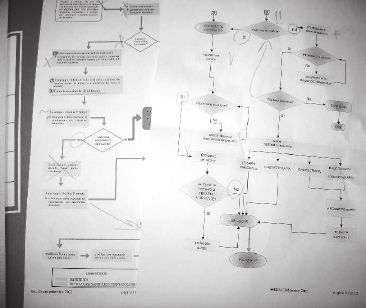

An intermediate case is offered by the use of

Clinical Pathways (CP), that is representations of

clinical care procedures that can be added to the

patient folder (EPR) and annotated by the doctors to

express the actual execution of the care plan with the

critical points and deviations from the standard path.

CPs can be defined by the doctors working in a ward

(as in (Cabitza et al, 2013), see Figure 2) or by

external institutions on the basis of some recognized

evidences.

In any case, the endogenous or exogenous

representation of the care procedure is augmented

“Objectivity” and “Situativity” in Knowledge It Artifacts - Incommensurable but Sensible Dimensions in Different Contexts

417

with information that expresses the choices made, the

criticalities meet and the workarounds followed

during the situated performance of the care procedure

and that constitute the inputs of a learning process for

whom has access to these pieces of information.

Figure 2: Clinical Pathways and their annotations.

In the last cases the pertinent KITA is an

application that offers the affordance of rich and

flexible annotation functionalities to enrich those

documents with information that contextualizes their

contents and that can evoke individual knowledge in

the mind of who writes and possibly in whom reads,

these annotations (Cabitza et al., 2005). In fact, this

contextualization can link annotations with specific

steps of the processes where the documents are used

or generated; it can convey information about the

applicability of some organizational rules and about

the workarounds that they generate in a given

situation; and so on.

We can generalize the use of flexible annotations

by considering them in combination with applications

that can be grouped under the umbrella of

(computational) supports where documents can be

archived, tagged, organized according to a (top-

down) strategy that can leave some possibilities to be

locally adapted; and where people can upload their

documents to be shared with (selected) colleagues

and look for and start conversations with them. These

are the typical affordances of the Enterprise Social

Media (ESM) that are increasingly introduced as light

KM tools within organizations. These ESM (or any

other technology that shares the same affordances)

could be constructed so as to facilitate the creation of

a common repertoire by the target group through the

introduction of functionalities that support the

negotiation of meanings, of which the annotations

proposed above are just an example.

The above examples show that the information

that collaborative professionals (that are engaged in a

collaborative learning process as part of their

activities) use and share can be separated into two

categories: the information that they collaboratively

construct and is fully under their control, that is what

we have characterized as a KA; and the information

that is made available to them “from outside”, that is

when the rules governing its creation (internal logic)

and maintenance (who is in charge of its changes and

updates) are defined by people outside the above

learning process (e.g., the management or some

professionals temporarily playing the role of

innovators who propose to modify the KA and the

related practices: these changes have still to be

appropriated by the other professionals).

In the first case, as already mentioned, the

technology should fully respect the situated practices,

avoiding any computational mechanisms that

introduce any sort of prescription in the aim to

guarantee “correct” behaviors and correct the “bad”

properties (such as underspecification, redundancy,

possible ambiguity). The competent professionals

know not only how to leave with them but especially

how to leverage them to understand (possibly by

additional negotiation of meanings) complex and not

yet experienced situations and to collaboratively find

the optimal solutions. Instead, when the available

information comes “from outside” it has to be

interpreted by the collaborative professionals under

the affordances and constraints of their current

situation. Here the rules governing the creation and

the maintenance reflect the logic of who is in control

of their definition: the receiving professionals have to

decide if they agree to comply with. As the examples

show, the KITA in this case should both support the

negotiation of meanings of what the given

information is about and help creating a connection

with the information managed by the component that

makes the local KA computational. The above

mentioned annotation functionality can be one, but

not the only one, typical example of such a support.

5 A ROOM FOR “OBJECTIVITY”

Now, as not all the groups of people interacting to

perform some interdependent and/or collaborative

actions according to a commonly understood purpose

can be considered as a CoP, it is likely that a KA

cannot be recognized, and even less can be

enforcedly introduced, in all collaborative settings.

This does not mean that the involved people are not

knowledgeable professionals: they simply did not

come to the point to be a CoP and to build their

shared repertoire accordingly. The reasons can range

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

418

from individual attitudes up to organizational

strategies in managing human resources, or any

combination of them. Whatever these reasons are, the

issue is how to promote and support learning under

these conditions to achieve all the typical goals of a

KM initiative from the management perspective (re-

use, preservation, training of newcomers, and so on)

without the possibility to leverage any recognizable

KA. This question can be rephrased in terms of the

two dimensions we have adopted to organize our

reflections: since the situativity dimension, or better

yet the related (design) practices hinted above, are not

practicable/applicable in this case, can the objective

dimension be of some help? and under which

conditions?

To answer this question we have to consider the

typical conceptual framework and tools that come

with the objectivity dimension: the knowledge

elicitation and representation methods that a

knowledge engineer applies to build a knowledge

base and the related inferences to support the

knowledgeable activities of a group of professionals

and the “sharing of the related knowledge”.

Are these framework and tools usable for achieving

the above goal? In our opinion, the answer is partially

positive as this would require some caveats.

6 A CHANGE OF PERSPECTIVE

We can say that those tools are applicable but the

conceptual framework does not. In other words, the

traditional goal of this “objectivistic” construction has

to be restated and the tools used accordingly. The

“objectivistic” conceptual framework is rooted in the

belief that it is possible to extract the knowledge from

the mind of the professionals in the aim to construct a

representation of this knowledge that is as complete

and coherent as possible. In case of conflicting

contents among the professionals the knowledge

engineer has to enforce a mediation through a

representation that is not so far from each

contributors’ perspective and for this reason can be

both accepted by them and serve as the basis for the

definition of the rules that would check the

correctness of the professionals’ actions/choices and

possibly provide them with adequate

recommendations.

We submit that the goal should be different:

namely, to trigger the professionals’ reflection about

their often unaware practices and about the artifacts

that they use to support them. The representation of

the experiences and practices that each professional

reports (typically, some representatives of them) does

not aim to a complete and fully coherent description:

under-specification, possible ambiguities and

conflicting contents with respect to other colleagues

have to be considered not as a fault, rather as an

occasion to open a discussion, a confrontation, a

negotiation of meanings. In this process, the

knowledge engineers offer their investigation and

representation tools and capabilities to keep trace of

what emerges, to highlight discrepancies and to

document them in the representations as a valuable

source of information to be shared in the whole group

of professionals.

Where does this process lead to? The outcomes

can be very different as too many factors (at the

individual, group and organization levels) can

influence this process. The most favourable outcome

is that the group comes to the point to collectively

behave as a CoP: it could adopt, amend, negotiate,

reformulate the above representations in a

collaborative way and these can become part of its

shared repertoire and be maintained as such.

Otherwise, this process can at least lead to various

degrees of mutual awareness about the fact that the

individual practices follow different patterns and to

different degrees and quality of the communication

within the group of professionals about these

practices: in any case, a potential mutual learning

process can start.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The conceptual separation between a KA and a KITA

that can potentially incorporate it allows one to avoid

the construction of a KITA without paying attention

on what are the implications on the work practices of

its users. These implications can encompass the

refusal or irrelevant usage of the proposed

technology; a low level of the ROI that is anyhow

necessary in any KM initiative; the hindering of a

virtuous learning process by an inadequate

technology; the emergence of even more hidden

practices to deal with knowledge creation and

diffusion in an organization, that is to go the opposite

way with respect the goals of any KM initiative; and

most importantly the possible waste of precious

resources (the KA and the shared practices around

them) that have been produced thanks to an almost

voluntary and hidden work of the organization

members (Suchman, 1995) to improve the learning

and the effectiveness of the problem solving needed

to reach the organization mission. In all these

situations, the balance is negative for both the

organization and its members.

“Objectivity” and “Situativity” in Knowledge It Artifacts - Incommensurable but Sensible Dimensions in Different Contexts

419

We are aware that knowledge can concern

different aspects of the organization life and by

consequence it can have different value; moreover

that this can influence the organization strategy to

“manage” them: often “core knowledge” is the term

used to refer to the most valuable knowledge

(Blumentritt and Johnston, 1999); consequently the

management is likely to invest more to protect, reuse

and preserve it. While protection is a serious issue

that requires a special attention in case of core

knowledge, we do not believe that its preservation

and reuse would require heavy weighted and

“objective” KM technologies to be supported. The

knowledge might regard more complex and crucial

phenomena, but its genesis and preservation is likely

to follow the same mechanism: in this case the

practices of competent professionals will be simply

suitable to master this complexity and will be

possibly reflected in KA that they might conceive

accordingly.

The considerations developed in this paper

concern a specific kind of artifacts: the empirical

work underpinning them considered various kinds of

documental artifacts. On the one hand, documental

artifacts are spread in many collaborative settings and

are used in many domains; on the other hand, it is

likely that other artifacts used to support

knowledgeable collaborative actions are of a different

nature. A further investigation is required to validate

the generalizability of our arguments to these kinds of

artifacts: however, we submit that the contents could

own different characteristics but the practices around

them should be almost of the same nature.

REFERENCES

Bardram, J. E., & Bossen, C. (2005). A web of coordinative

artifacts: collaborative work at ahospital ward. In

Proceedings GROUP 2005 International ACM

Conference, ACM Press, 168–176

Berger P. L, & Luckmann T., (1967) The Social

Construction of Reality: ATreatise in the Sociology of

Knowledge. Anchor Blackler, F. (1995). Knowledge,

knowledge work and organizations: An overview

andinterpretation. Organization Studies, 16(6), 1021–

1046.

Blumentritt, R., & Johnston, R., (1999). Towards a strategy

for knowledge management. Technology Analysis &

Strategic Management, 11(3), 287-300.

Cabitza, F., (2013). At the boundary of communities and

roles: boundary objects and knowledge artifacts as

complementary resources for the design of information

systems. From Information to Smart Society:

Environment, Politics and Economics. LNISO.

Springer, Berlin.

Cabitza, F., Colombo, G., & Simone, C., (2013).

Leveraging underspecification in knowledge artifacts to

foster collaborative activities in professional

communities. International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, 71(1), 24-45

Cabitza F., Simone C., Locatelli M. P., (2012) Supporting

artifact-mediated discourses through a recursive

annotation tool. In Proceedings of the International

GROUP 2012 ACM Conference, ACM Press, 253–262.

Cabitza, F. & Locoro, A., (2015). “Made with Knowledge”:

disentangling the IT Knowledge Artifact by a

qualitative literature review. In J. Dietz, K. Liu, & J.

Filipe (Eds.), 5th International Joint Conference IC3K

2014, (Vol. Forthcoming) Springer, 64−75..

G. De Michelis, (2012). Communities of practice from a

phenomenological stance: lessons learned for IS design.

In: G. Viscusi, G. M. Campagnolo, Y. Curzi, Eds.:

Phenomenology, Organizational Politics and IT Design:

The Social Study of Information Systems, IGI Global,

57-67

Kakihara, M. & Soerensen, C., (2002). Exploring

knowledge emergence: From chaos to organizational

knowledge. Journal of Global Information Technology

Management, 5(3), 48–66.

McDermott, R. (1999). Why information technology

inspired but cannot deliver knowledge management.

California Management Review, 41(4), 103–117.

Munkvold, G., Ellingsen, G., & Monteiro, E. (2007,

November). From plans to planning: the case of nursing

plans. In Proceedings of the International GROUP 2007

ACM Conference, ACM Press, 21-30.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge

Creating Company. Oxford University Press.

Schmidt, K. & Wagner, I., (2004). Ordering systems:

Coordinative practices and artifacts in architectural

design and planning. Computer Supported Cooperative

Work (CSCW), 13(5-6), 349-408.

Suchman L., (1995). Making work visible, Communiations

of the ACM Vol. 38, No. 9, 56-64.

Wenger E., (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning,

Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

420