Debate Formed by Internet Comments

Towards the Automatic Analysis

Mare Koit

Institute of Computer Science, University of Tartu, 2 J. Liivi St., Tartu, Estonia

Keywords: Debate, Internet Comment, Opinion, Judge, Winner.

Abstract: Together with an increasing role of online media in human communication it is necessary to perform

automatic analysis of online texts. In this paper, we are studying dialogues formed by opinion articles and

their comments on Internet. Such a dialogue can be considered as debate between two teams. One team

connects the commentators with positive and another – with negative comments about the initial opinion,

i.e. the commentators who respectively, support or reject the opinion presented in the source text. The

members of both teams can in any time have the floor what is different as compared with conventional

spoken debate. Internet users who spontaneously give marks +1 or -1 to the comments act as a board of

‘judges’. The winner is the team with a bigger total sum of marks. For every comment, we also assign a

point in a mental space which we call communicative space. The values +1, 0 or -1 of the coordinates of

communicative space make it possible to classify the comments not only as positive and negative but also as

polite and impolite, friendly and hostile, etc. The set of comments forms a collective opinion about the main

agent of the source text which introduces a social aspect into the text analysis. The further aim of this

preliminary study is the automatic analysis of such debates.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this paper, we will consider a special kind of

online debates. As known, debate is a discussion

between two participants (or two teams) with

conflicting interests. Every speaker provides

arguments against the opponent’s statements and in

support of their own statements and finally, one of

them wins debate (reaches his/her communicative

goal) and another loses (has to withdraw) (Walton et

al., 1995; Koit, 2015). When initiating a debate,”a

speaker asserts a proposition expecting to be asked

for reasons/arguments in support of it and being

prepared to present and defend them” (Wagner,

1998).

Debate is a contest where the participants

attempt to convince each other, judges and observers

that their position about the topic of the debate is

right and better than the opponent presents. Two

teams – one who affirms and another who disclaims

the initial position prepare to defend their own

positions. The judges evaluate the arguments of the

participants using the criteria as agreed beforehand

and finally, declare the winner (Kennedy, 2009;

Murphy, 1989).

Many researchers have been modelling

argumentation dialogue on the computer and

investigating formalization of argument. An

overview of the area can be found e.g. in (Besnard

and Hunter, 2008).

A formal model of debate about doing an action

has been introduced in (Koit and Õim, 2014). The

communicative goal of the initiator is to convince

the partner to do an action. He presents several

arguments for the usefulness, pleasantness, etc. of

doing the action and his partner presents

counterarguments. The initiator uses a reasoning

model in order to select suitable arguments. The

partner also uses a reasoning model (which can be

different) in order to make a decision about the

action. The initiator will achieve his goal if he

succeeds to influence the reasoning of the partner by

presenting good arguments. The model of debate

also includes a formal model of argument.

A discontinuous ’dialogue’ formed by an Internet

opinion article and its comments has been analysed

in (Hennoste et al., 2010). Despite the fact that a

written interaction has been studied, it turned out

that principles of analysing spoken conversation can

be applied as established in Conversation Analysis

328

Koit, M..

Debate Formed by Internet Comments - Towards the Automatic Analysis.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 2: KEOD, pages 328-333

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

(Hutchby and Wooffitt, 1998). A dialogue starts

with a source text which can be considered as the

first pair part (a dialogue act) of an adjacency pair

(AP) which expects a reaction (another dialogue act)

of the partner (like an opinion expects agreement or

rejection). Comments which confirm or reject the

opinion expressed in the source text will follow as

the second pair parts of this AP. The next

commentator can respond to the source text or to

some comment. In this way, a dialogue is formed by

occurring parallel micro-dialogues each consisting

of one AP: source text (opinion) – comment 1

(agreement or rejection), source text (opinion) –

comment 2 (agreement or rejection), etc. On the

other hand, longer sub-dialogues can appear if a

commentator gives his/her opinion which turns out

to be the second pair part of a previous AP and at the

same time, the first pair part of a new AP eliciting a

new reaction. The following comment

simultaneously can be considered as the second pair

part of this AP and as the first pair part of a new AP,

and so on.

In this paper, we will undertake a preliminary

study of a dialogue formed by an opinion article

published on Internet and its comments. We

consider it as debate between two teams: one team

gives positive and the other – negative comments in

relation to the opinion expressed in the source text.

We can determine the winners and the losers of

debate by using a voting device usually added to an

Internet portal, with help of which everyone can

evaluate every comment by giving the marks +1 or

-1. Finally, the marks can be summed up and the

winner will be the team with a bigger total sum of

marks.

We also use another way to evaluate the

comments by annotating them as ’points’ in

’communicative space’. Our further aim is the

automatic analysis of such debates.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2

demonstrates how a source text and its comments on

Internet can be considered as debate and how

winners and losers can be determined. Section 3

introduces communicative space and describes how

the comments can be represented as points in

communicative space. Section 4 discusses some

classification problems of comments. Section 5

makes conclusions.

2 DEBATE FORMED BY

INTERNET COMMENTS

An inherent dialogue structure is established by the

conglomeration of an Internet opinion article and its

comments as shown in (Hennoste et al., 2010). The

core structure of the dialogue is formed by micro-

dialogues consisting of two turns: the source article

which expresses an opinion and its comment which

can be considered as an argument for or against the

initial opinion. Another (typically smaller) group of

comments are not necessarily associated with the

source text but they are directly related to some

previous comment. Thus, coherent parallel sub-

dialogues arise like in the spoken conversation. The

relations between turns are formed following the

social norms of building APs (opinion –

agreement/rejection) in spoken face-to-face

interactions, even though the participants do not

have responsibility for the maintenance of the

conversation.

An opinion text expresses a position of the

author or of the main agent. The commentators when

giving their own opinions can take this same or

opposite position. The commentators with the same

position can be considered as one team in debate

(‘yes’-team, proponents) and these who have the

opposite position form another team (‘no’-team,

opponents). The members of the teams do not take

the floor in the fixed order like in conventional

spoken debate. On the contrary, every commentator

can in any time enter into debate and express his or

her positive or negative opinion about the source

text or some previous comment. Everyone can also

leave from debate in any time.

Every positive or negative comment can be

considered as an argument for or, respectively,

against the initial opinion.

An argument has been defined as a pair ({H,

p},h) where p is a proposition, {H, p} is a subset of

the knowledge base where: i) {H, p} is consistent, ii)

{H, p} infers h, iii) {H, p} is minimal (for set

inclusion) (Amgoud and Cayrol, 2002; Besnard and

Hunter, 2008; Koit and Õim, 2014). Here {H, p} is

called the support and h the conclusion of the

argument.

In the case of debate formed by an Internet

opinion article and its comments, p is the statement

presented in a comment, H is (implicit) knowledge

in mind of the commentator used by him or her in

order to form the statement and conclusion h is an

opinion of the commentator – agreement or

rejection, depending on the side chosen by him or

her in relation to the initial opinion expressed in the

source text.

The algorithm for creating such a debate is as

follows (Figure1).

Debate Formed by Internet Comments - Towards the Automatic Analysis

329

Source_text

For every commentator do

Choose the side (‘yes’ or ‘no’)

If the side=‘yes’ then present

argument_for

If the side=‘no’ then present

argument_against else present

neutral_statement

Figure 1: Creating debate by Internet commentators.

Let us consider an example from the Estonian

corpus of Internet comments

1

that we are using as

development data – an interview („Radical Margus

Lepa would reconstruct Estonia“)

2

together with its

comments published on the Estonian Internet portal

Delfi on October, 31, 2014. The interviewer is a

journalist and the interviewee (the main agent of the

source text) is Margus Lepa currently working as an

editor of a local radio. Lepa is characterized by his

radical views, and he is a former artist, a well-known

person in Estonia. The topic of the text is the

economic and political situation in Estonia. Lepa’s

main statement is expressed in his sentence: „One

reform follows after another but nothing will be

better.” Therefore, Lepa’s opinion is that Estonia

needs reconstruction (as stated in the title of the

article). The source text was published at 10:31 and

it got 87 comments in total. The first comment

arrived on October, 31, 2014 at 10:49 and the last

one much later, on December, 13 at 18:11.

Commentators express their positive or negative

opinion about the views of the agent of the source

text (Lepa).

The first two comments are positive, i.e. the

commentators assign themselves to the ’yes’-team,

agreeing with Lepa.

(1)

väga hea/ very good 31.10.2014 10:49

jõudu M.Lepale , pane samas vaimus edasi ./

more power to M.Lepa, keep it up.

(2)

Tubli/ Fine 31.10.2014 11:07

Nõmme Raadio on ainuke raadio kus tuuakse

meie riigi mädapaised kuulajate ette mida muu

meedia püüab katta statistikaplaastriga./ Radio

Nõmme is the only radio which emphasizes the

1

http://keeleressursid.ee/en/resources/corporahttp://

keeleressursid.ee/en/resources/corpora

2

http://eestielu.delfi.ee/eesti/laane-virumaa/rakvere/elu/-

radikaalne-margus-lepa-saneeriks-eesti-riigi.d?id=

70058739&com=1-®=1&no=0&s=1

abscesses of our country what other media attempts

to hidden with a statistical plaster.

The following two are examples of negative

comments, i.e. the commentators assign themselves

to the ’no’-team.

(3)

ettevõtlik tola/ a pushing fool 31.10.2014 11:08

radikaalne vingats/ a radical whiner

(4)

Hea nõu!/ Good advice! 31.10.2014 11:13

Algul tuleks oma ajusi saneerida ja siis tulevad

vastused ja med.teemal ka! / First, he should clean

his brain and after that the answers and also

medical topics will come in!

The total number of the positive comments is 44

and the number of negative ones is 18. Some

comments are reactions to previous comments, i.e.

they do not directly react to the source text. A

positive (resp. negative) comment to an earlier

positive comment is accounted as positive (resp.

negative). A positive (resp. negative) comment to an

earlier negative comment is calculated as negative

(resp. positive). There are 9 comments which

include two opinions about different statements, one

of them is positive and another negative. Such

comments are calculated twice. Further, there are

also neutral comments that do not express neither

positive nor negative opinion about the source text

or the main agent; their number is 16. Can we

conclude that the ’yes’-team wins this debate? No,

because we need to involve some judges who

calculate not only the numbers of comments but also

take into account their content like in conventional

debate. All the same, we can use a voting device

provided by the Internet portal. Every user (not only

a commentator) can push one of two buttons beside

a comment giving positive (+1) or negative (-1)

feedback regarding this comment. Every click

increases (or decreases) the total grade of the

comment by one unit. A user may vote only once

(this is checked according to IP-addresses of

computers). In this way, all the voters play at a jury

of judges who evaluate the comments (‘arguments’).

For example, the comment (1) got 290 voices for

and 25 voices against; the comment (3) got 26

voices for and 133 voices against, etc. Neutral

comments have been excluded from calculations.

Finally, summing up the grades of positive and

negative voices both for positive and negative

comments we can conclude that the ’yes’-team has

won this debate. Therefore, the opinion that Estonia

needs reconstruction predominates.

KEOD 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

330

3 COMMUNICATIVE SPACE

The commentators who participate in debate express

themselves differently: friendly or unfriendly,

politely or impolitely, personally or impersonally,

etc. Healey et al. (2008) declare that “there are

important differences in the quality of human

interaction – in degrees of interpersonal, as opposed

to physical, closeness – that are important for the

organization of human activities and, consequently,

for design”. They suppose that the concept of

communication space provides a useful approach to

thinking about the basic organization of human

interaction. Communicative space is also considered

in (Brown and Levinson, 1999).

We use here the notion of communicative space

in order to introduce an additional classification of

Internet comments. We represent communicative

space as an n-dimensional space (n > 0) where

different coordinates characterize the different

features of communication. We specify the

following six features (Koit, 2015): 1)

communicative distance between participants (which

can be measured on the scale from familiar to

remote), 2) cooperation (from collaborative to

confrontational), 3) politeness (from polite to

impolite), 4) personality (from personal to

impersonal), 5) modality (from friendly to hostile),

6) intensity (from peaceful to vehement). The values

of the features can be expressed by specific words in

a natural language, e.g. ’very near’, ’familiar’,

’neutral’, ’far’, ’very far’, etc. for communicative

distance. Instead of different words, we limit us with

three values for every feature and use the numbers

+1, 0 and -1 as approximations to the words. For

example, the value +1 on the scale of modality

means that the participant is ’friendly’ in relation to

his or her partner; the value 0 marks ’neutral’ and

the value -1 ’hostile’ modality. In this way, a feature

vector can be assigned to every comment that

determines a point in communicative space where

the author of the comment is just located.

Let us consider the examples (Section 2) once

more. Most of the comments (both positive and

negative) can be characterized by a feature vector (0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0), i.e. the values of all coordinates are

’neutral’ like in the case of most of institutional

interactions where the participants try to restrain

their temper. An example of such a comment is (5).

(5)

Jõudu tegijale/ more power to the worker

31.10.2014 10:57

Lepa on asjalik mees ja kui “valitud” võtaksid

kuulda kas või 1% M.L. jutust, siis me elaksime

palju paremas ja inimsõbralikumas riigis./ Lepa is a

practical man and if the ‘selected persons’ would

accept at least 1% of his talk then we would live in a

much better and friendlier country

Communication point (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)

At the same time, there are comments where the

author does not keep a neutral position. For

example, the author of the comment (1) is located in

the point (+1, 0, 0, +1, 0, 0). Both communicative

distance and personality have the value +1 as

indicated by the singular form of imperative mood

(pane/ keep [singular] vs. pange/ keep [plural]). The

usage of imperative indicates that the comment is

personally directed to the main agent what is

different as compared with the comment (5).

The comment (3) represents the point (-1, -1, -1,

+1, -1, -1) which indicates that the author hotly

disparages the main agent of the source text; the

comment is directed against a certain person and the

language usage is impolite (radikaalne vingats/ a

radical whiner).

4 DISCUSSION

As shown in Section 2, a dialogue formed by an

Internet opinion article and its comments can be

considered as debate. Every Internet user can at any

time give one or more comments about the source

text or some previous comment. When starting to

write his or her comment, the commentator selects a

side determining does (s)he agree or not with the

opinion presented in the article. Therefore, two

teams will be formed – one which supports and

another which rejects the opinion expressed by the

author or by the main agent of the initial article. This

in a manner is different as compared with

conventional spoken debate because the members of

both teams can at any time have the floor and the

number of their speaking is not limited. Some

commentators can stay on a neutral position if they

do not select neither positive nor negative side.

The core structure of such a dialogue is formed

by micro-dialogues consisting of two turns: the

source article and its comment like stated in

(Hennoste et al., 2010). Another group of comments

are not necessarily associated with the source text

but they are directly related to some previous

comment. Thus, coherent parallel sub-dialogues are

formed like in the spoken conversation.

The comments can be classified as positive and

negative (and neutral) depending on their agreement

or not-agreement with the initial opinion expressed

Debate Formed by Internet Comments - Towards the Automatic Analysis

331

in the source text. By different kinds of comments a

‘portrait’ of the main agent of the source text is

formed; we can see how positive and negative

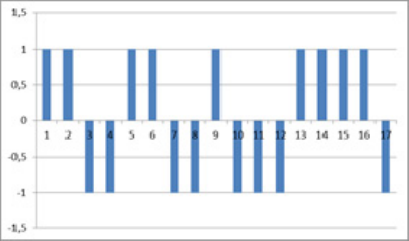

comments alternate during a dialogue. For example,

the first 17 comments to the opinion article

considered in Section 2 were given during the first

hour after the publication of the article. The numbers

of the first positive and negative comments are

almost balanced and give a partial portrait of the

main agent as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: ‘Portrait’ of the main agent of the source article

formed by the first 17 comments (the values +1 or -1).

However, the number of following positive

comments outweighs the number of negative ones

and the final portrait of the main agent turns out to

be positive (if to take into account only the numbers

of comments). Majority of the commentators agrees

with the main agent that Estonia needs

reconstruction. However, such a picture of an agent

(in the given case positive) represents a collective

opinion only of a small group of people (who have

commented the source text) and it can’t be counted

as a general public opinion.

A group of Internet users (‘judges’)

spontaneously evaluates the comments positively or

negatively. In our example, the total sum of marks to

the positive comments is much bigger than the sum

of marks to the negative ones. Therefore, most

people who have commented the article or evaluated

the comments support the opinion expressed in the

article. The team who supports opinion of the main

agent wins debate and the team of opponents loses.

Again, this is a collective opinion of this certain

group.

We evaluate the comments also by using the

notion of communicative space where each

coordinate (feature) has a value +1, 0, or -1. The

features represent communicative distance between

a commentator and the main agent, collaboration

with the main agent, politeness, etc. A feature vector

can be assigned to every comment which

characterizes (the author of) the comment. The

comments can be classified on the basis of every

feature depending on its value. For example, there

are polite, impolite and neutral comments (if to

consider politeness), or there are friendly, unfriendly

and neutral comments (if to consider modality), etc.

There can be positive comments which are impolite

and negative comments which are polite, etc., i.e. the

value +1 (respectively, -1) of a coordinate of

communicative space does not mean that a comment

itself is positive (respectively, negative) in relation

to the initial opinion. These classifications make it

possible to bring social aspects into the analysis of

Internet texts.

In our analysed examples, we have manually

classified the comments as positive, negative and

neutral. We have also manually determined the

values of the coordinates in communicative space

for every comment. For automatic classification –

which is our further aim – opinion (or sentiment)

analysis can be used in order to determine the

contextual polarity of a text. Several methods can be

applied: concept-level techniques, statistical

methods, keyword spotting, lexical affinity (Pang

and Lee, 2008). Many opinion mining approaches

find negative and positive words in a text, and

aggregate their counts to determine the final

document polarity. In (Somasundaran et al., 2007),

automatic classifiers have been developed for

recognizing two main types of attitudes: sentiment

and arguing. They exploit information about the

attitude types of questions and answers for

improving opinion question answering. Some work

has been done on detecting arguing subjectivity – a

type of linguistic subjectivity in which a person

expresses a belief about what is true. The argument

being expressed through each instance has to be

identified in terms of arguing subjectivity and

argument tags (Conrad et al., 2012). In

(Somasundaran and Wiebe, 2009), the debate side

classification task, i.e. recognizing which stance a

person is taking in an online debate is formulated as

an Integer Linear Programming problem. Factors

that influence the choice of a debate side are learned

by mining a web corpus for opinions. This

knowledge is exploited in an unsupervised method

for classifying the side taken by a post.

In order to determine adjacency pairs of

comments in an Internet debate, i.e. to decide is a

comment directly related to the source text or is it a

response to some previous comment we need to

recognize dialogue acts. Some work for Estonian has

been done in (Aller et al., 2014). Still, Internet

portals (e.g. Delfi) usually make it possible to link a

comment directly with a previous comment if

needed.

KEOD 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

332

5 CONCLUSIONS

We are studying debates formed by the

conglomeration of an Internet news article and its

comments with the further aim of their automatic

analysis. A source text introduces some opinion and

the following comments either support or reject this

opinion. Departing from Conversation Analysis, the

source text can be considered as the first pair part

and its comment as the second pair part of an

adjacency pair (of dialogue acts). A comment (as an

opinion) can also initialize a new AP if one of the

next comments reacts to it (and therefore can be

considered as the second pair part of this AP). In

general, debate consists of micro-dialogues most of

which include one single AP. The commentators as

participants of debate belong to one of two

competing teams. One of them, ‘yes’-team, proposes

positive comments agreeing with the opinion

expressed in the source text, and another, ‘no’-team,

makes negative comments. The winners and losers

will be determined by ‘judges’ – the Internet users

who read the comments and give them the marks +1

or -1. The winner is the team with a bigger sum of

marks. Positive and negative comments in total give

an image (a portrait) of the main agent of the source

text. If positive comments overweigh then the

opinion expressed in the source text is approved by

the commentators and evaluators. Every comment

represents a point in communicative space which

can be characterized by a number of coordinates –

the features with the values +1, 0, or -1. These

values make it possible to introduce additional

classifications of comments (e.g. collaborative or

antagonistic, friendly or unfriendly, etc.). Evaluation

of the presented ideas, incl. automatic classification

of comments remains for the further work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Estonian Research

Council (grant IUT20-56).

REFERENCES

Aller, S., Gerassimenko, O., Hennoste, T., Kasterpalu, R.,

Koit, M., Laanesoo, K., Mihkels, K., Rääbis, A., 2014.

Software for pragmatic analysis of dialogues [in

Estonian]. In Estonian Papers in Applied Linguistics,

23–36.

Amgoud, L., Cayrol, C. 2002. A reasoning model based

on the production of acceptable arguments. In Ann.

Math. Artif. Intell., 34(1-3), pp. 197–215.

Besnard, P., Hunter, A., 2008. Elements of Argumentation.

MIT Press, Cambridge, MA,

Brown, P., Levinson, S.C., 1999. Politeness: Some

universals in language usage. In A. Jaworski, N.

Coupland (eds.). The discourse reader, 321–335,

London: Routledge.

Conrad, A., Wiebe, J., Hwa, R., 2012. Recognizing

Arguing Subjectivity and Argument Tags. In Proc. of

ExProM, 80-88.

Healey, P.G.T., White, G., Eshghi, A., Reeves, A.J., Light,

A., 2008. Communication spaces. In Computer

Supported Cooperative Work, 17:169–193. Springer.

DOI: 10.1007/s10606-007-9061-4

Hennoste, T., Gerassimenko, O., Kasterpalu, R., Koit, M.,

Laanesoo, K., Oja, A., Rääbis, A., Strandson, K.,

2010. The structure of a discontinuous dialogue

formed by Internet comments. In Sojka, P., Horak, A.,

Kopecek, I., Pala, K. (Eds.). Text, Speech and

Dialogue, 515–522. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-

Verlag.

Hutchby, I., Wooffitt, R., 1998. Conversation Analysis.

Polity Press, Cambridge.

Kennedy, R.R., 2009. The power of in-class debates. In

Active learning in higher education, 10, 3, 225-236.

Koit, M. 2015. Communicative strategy in a formal model

of dispute. In Proc. of ICAART, 489–496. Lisbon,

Portugal, SciTePress.

Koit, M., Õim, H. 2014. Modelling debates on the

computer. In Proc. of KEOD, 361–368. SciTePress.

Murphy, J. J., 1989. Medieval Rethoric: A Select

Bibliography. University of Toronto Press.

Pang, B., Lee, L., 2008. Opinion mining and sentiment

analysis. In Foundations and Trends in Information

Retrieval, vol. 2, No 1-2, 1–135.

Somasundaran, S., Wilson, T., Wiebe, J., Stoyanov, V.,

2007. QA with attitude: Exploiting opinion type

analysis for improving question answering in on-line

discussions and the news In ICWSM, 8 pp.

Somasundaran, S., Wiebe, J., 2009. Recognizing stances

in online debates. In ACLAFNLP, 226–234.

Wagner, G., 1998. Foundations of Knowledge Systems

with Applications to Databases and Agents. Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Walton, D., Krabbe, E.C.W., 1995. Commitment in

Dialogue. Albany, SUNY Press.

Debate Formed by Internet Comments - Towards the Automatic Analysis

333