Understanding Factors Influencing Teachers' Use of

Technologies in Teaching STEM

Georgia L. Bracey and Mary L. Stephen

Center for STEM Research, Education & Outreach, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville,

Edwardsville, Illinois, U.S.A.

Keywords: Technology, Teachers, STEM, Secondary Education, Teacher Learning Preferences, Teacher Perceptions of

Technology, Teacher Beliefs, Autonomy.

Abstract: Teachers’ adoption of technology continues to be challenging; yet, this is a critical process in the effective

teaching of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Although more schools are

providing technology-rich classrooms, teachers are not always incorporating the new technologies into their

teaching practice in a meaningful way. In this three-year case study, we used a grounded theory approach to

examine the experiences of two high school teachers working in a depressed urban setting as they began

using a newly designed, innovative, high-tech STEM classroom. Data sources included semi-structured

interviews and direct observation. We identified three themes related to technology use: personal learning

preference, teaching philosophy, and perception of technology. We discuss these themes, highlighting

examples from participants’ experiences and beliefs, as well as other factors impacting technology use that

emerged during the study. These results will be of value to those supporting teachers’ integration of

technology into their teaching practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

The successful introduction of technology into a

teaching setting is influenced by a series of factors

(Afshari, et al., 2009; Angers and Machtmes, 2005;

Buabeng-Andoh, 2012; Mumtaz, 2000). The

interaction of these factors is complex, and plays an

important role in determining the extent and ways

that technologies are used within a setting. Teachers

bring their own unique experiences and

backgrounds, skills, and attitudes about technologies

and education into the teaching environment

(Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development [OECD], 2009), and these elements

have the potential to impact the teacher’s

understanding of the affordances and constraints for

using technologies in teaching. In this paper, we

report the findings from a three-year study which

documented two teachers’ experiences teaching in

an innovative, technology-rich Science, Technology,

Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) classroom in

an attempt to identify and understand factors

influencing the teachers’ decisions on whether and

how to use the new technologies in their teaching.

The adoption of technology by STEM teachers is

seen as critical to student success in STEM, as

technology use has been linked to increased interest

in and engagement in STEM activities, leading to

improvements in STEM teaching and learning

(Nugent, et al., 2010). Technology-based lessons are

viewed as more authentic, giving students the

opportunity to engage in real-world STEM activities

and to use equipment similar to that which real

STEM professionals would use (Hanson and

Carlson, 2005). Unfortunately, there is disparity in

the availability of and access to technologies needed

to teach STEM, as schools in low-income

communities do not always have the materials,

laboratories, and equipment to teach these subjects

effectively (Flores, 2007; Margolis, et al., 2008). In

a recent Pew Research Center report (2013), 56

percent of teachers of the lowest income students

indicated that a lack of resources among students to

access digital technologies is a “major challenge” to

incorporating more technology into their teaching.

However, even when sufficient technology is

available, teachers’ adoption of technology

continues to be a serious issue. While having

sufficient and up-to-date resources available is

important for STEM teaching and learning,

resources alone do not guarantee improved student

127

L. Bracey G. and L. Stephen M..

Understanding Factors Influencing Teachers’ Use of Technologies in Teaching STEM.

DOI: 10.5220/0005493101270138

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 127-138

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

outcomes. Even when technology is used in

instruction, it is often not truly transformative or

innovative and merely mimics what has always been

done in the traditional classroom. In a study

involving over 1,000 students, Wang et al. (2014)

found that the majority of students reported using

computers in a school setting primarily for word

processing and Internet searches, not for problem

solving or creative activities. Although several

research studies have identified possible reasons for

this ineffective use of technology by teachers (e.g.,

lack of time, insufficient training, lack of

confidence, technical issues, etc.) (Bingimlas, 2009;

Buabeng-Andoh, 2012; Byrom and Bingham, 2001;

Wang, et al., 2014; Zhao and Frank, 2003), there

appears to be no significant improvement in the

situation (Pew Research Center, 2013).

For successful technology adoption to occur,

Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich (2010) believe

teachers need to change their mindsets to accept the

idea that “effective teaching requires effective

technology use” (p. 256). However, change, whether

in mindset or practice, is not easy. The experiences

and beliefs that teachers bring to the classroom have

a major impact on instructional practices and

willingness to change those practices (OECD, 2009;

Roehrig, et al., 2007). Thus, when innovations are

introduced into an educational setting, teachers

require time and support before the innovations can

be adopted and implemented to any substantial

degree (Hall and Hord, 2011). The study described

in this paper is an attempt to understand how and to

what extent change occurs in a particular classroom

setting given an influx of innovative technologies for

teaching and learning STEM. We were guided by

two broad questions: What factors influence the

ways and the extent that a teacher uses the newly

available technologies when teaching in a high-tech

STEM classroom? How does the availability and use

of the new technologies change teaching practices?

2 METHOD

In seeking to understand the complex interplay of

factors involved in teacher and technology use, we

used a qualitative case-study design. This design

enabled us to acquire and interpret data from

multiple perspectives within the natural setting

(Patton, 2002; Yin, 2009) and to "describe the unit

of study in depth and detail, in context and

holistically” (Patton, p. 54). The variety and detail of

data allowed us to create a rich story of the

participants and their experiences over the course of

the study.

2.1 Setting

McCloud High School (pseudonym), the setting for

this study, is an underperforming public secondary

school located in a U.S. city in a large metropolitan

area. According to 2013 data, 97 percent of the

residents of the city are African American with 41

percent of households classified as being below the

poverty level. In June 2014, the unemployment rate

in the city was 13 percent.

McCloud High School has been in existence for

approximately 17 years. During the three years of

the study, the school averaged 110 students all of

whom were African American and between the ages

of 13 and 19 years. The school employs three full-

time STEM teachers and offers a range of STEM

courses, requiring students to successfully complete

three years of mathematics and three years of

science in order to graduate. In 2012, the school

began to introduce courses from a pre-engineering

program, Project Lead the Way (PLTW), into the

curriculum.

In 2011, the school received a major gift for

construction of a classroom containing a variety of

innovative technologies, including 3D printer, video

wall, robotics kits, humanoid robot, graphing

calculators, iPads, and high-definition video

conferencing. This STEM classroom was designed

with teacher and student input, along with guidance

from the director of a nearby university’s STEM

Center, to be a flexible, high-tech learning space that

fosters collaboration and creativity. The classroom

and its technologies represented an educational

innovation with the potential to catalyze major

changes in teaching practice. Prior to construction of

the STEM classroom, the school had access to two

outdated computer labs that often were not fully

operational. Most of the school’s traditional

classrooms have a projector and teacher laptop, and

a few of the classrooms have been equipped with

SMART boards.

The study began with the initial planning for the

STEM classroom in late spring of 2011 and ended in

the summer of 2014. Both of us who served as

researchers for this study are researchers affiliated

with the university’s STEM Center. We conducted

all data gathering and analysis. In our role as

researchers, we attended meetings and other events

associated with the school and the new classroom

(e.g., visits to high-tech schools, STEM classroom

open house, monthly STEM staff meetings) in order

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

128

to better understand the environment. We also

supported logistical aspects of the classroom's

implementation, often helping to coordinate events

between the high school and the university or other

external groups, and so had regular opportunities to

interact with the participants.

2.2 Participants

We chose our two participants purposefully in order

to obtain the most meaningful, relevant, and detailed

information possible. Both Ms. Beech and Mr.

Aspen (pseudonyms) were full-time STEM teachers

employed at McCloud throughout the entire time of

the study and have been closely involved with the

STEM classroom from its early design through its

final implementation. Additionally, both teachers

attended project planning meetings for the new

classroom, providing valuable input to the design

team on the room's layout, furniture, and technology.

They also made several visits to high-tech schools

and participated in technology-focused professional

development. They began teaching in the room as

soon as its construction was complete and continue

to teach in the room as of this writing, giving

feedback on their experience to the project partners

at regular monthly meetings. Their continuous,

close involvement with almost all aspects of the

STEM classroom made them ideal sources of

information regarding its impact on teaching

practice at the school.

Ms. Beech is an African-American female in her

sixties. At the time the research study was initiated,

she had been teaching science and math at McCloud

High School for four years. She had previously

taught science for two years immediately after

graduating from college in the late 1960s, but then

entered the business world as an IT professional. She

reported having a very satisfying career, saying “I

really, really enjoyed IT in my day. There was such

a joy in designing and building systems and making

them work.” She retired from this work after 37

years, during which time she filled many roles from

programmer to analyst to manager and also earned a

master’s degree in business administration (MBA).

After retirement from her IT position, she returned

to school to earn a master’s degree in teaching

science. She continues to increase her knowledge

and skills as a teacher by participating in a local

university’s professional development program

designed to improve science teaching and student

learning. During the time of this study, she taught a

variety of courses including biology, chemistry,

physics, pre-calculus and anatomy. She also

participated in summer workshops to prepare her to

teach an introductory PLTW course. Ms. Beech

believes it is her responsibility to share with her

students what she has learned: “I took all those

courses … and so it would be a sin not to give them

everything I got.” Her teaching style involves a lot

of interaction with the students and checking

individual students’ understanding of concepts: "[I

want] to know what each individual is doing as

opposed to one or two people...I talk to them all the

time. I’m living and breathing example of ‘this is

what you do in life.’” She believes that in addition to

helping students get “a better, deeper understanding

of the concepts,” she has an important responsibility

to help students learn to use what they already know,

to think creatively, and to acquire “habits that will

help them get through” life.

Mr. Aspen is a Caucasian male in his twenties.

When the research study began, Mr. Aspen was in

his first year of teaching after having completed a

bachelor’s degree in biology and a master’s degree

in teaching science. He became familiar with

McCloud High School through his time as a student

teacher there. His teaching responsibilities included

algebra, geometry, general science, and introduction

to engineering. In addition, he assisted with the

school’s robotics team and a university-sponsored

game design club. Mr. Aspen is very comfortable

with a range of technologies. As he approached his

fourth year teaching, he decided to enroll in an

online master’s program in computer science

because of his interest in technology and the

flexibility such a program offers. Mr. Aspen

described mastering more “problem solving skills”

as one of the main goals he has for his students. He

added: “[I want them] to be able to do a lot of

different things pretty well or come up with different

answers rather than be able to do [one thing] like

integrals or quotients really well.”

2.3 Data Collection & Analysis

Primary data sources included a series of semi-

structured interviews and direct observations in both

the traditional and STEM classrooms. Interviewing

began during the design of the room so as to get an

understanding of each teacher's background and

their experience teaching in their regular classroom.

Over the course of the study, we conducted three

hour-long interviews with each participant as well as

a final ‘participant check’ interview. The initial

interview protocol included questions on the

participants’ education and teaching history, use of

technology, and classroom environment.

UnderstandingFactorsInfluencingTeachers'UseofTechnologiesinTeachingSTEM

129

Subsequent interviews were more open, allowing for

the flexibility to pursue emerging themes and issues.

Observations began early in the project, again to

get a sense of the teachers' experiences in the context

of their regular classroom. Later, after completion of

the classroom, participants were observed in both

the STEM classroom and a regular classroom. When

possible, we observed the same class taught in both

a traditional and the STEM classrooms. Together,

we observed each teacher numerous times, giving us

direct experience with the school setting plus the

opportunity to notice things that might otherwise

seem routine (and therefore go unmentioned) by the

participants (Patton, 2002).

As with any qualitative study, data analysis

began and overlapped with data collection. We used

NVivo software to facilitate the analysis, but also

coded much of the data manually. Field notes were

taken by hand. Interviews were audio recorded, then

transcribed by one of us or by a graduate student

assistant. Although we always interviewed and

observed our participants together, we coded the

transcribed data independently, using a constant

comparative process as described by Corbin and

Strauss (1990). We began with open coding--reading

through transcripts and looking for meaningful units

of data. These units of data were then grouped into

categories. The development of these categories--or

themes--was guided by our research questions as

well as by patterns that emerged. As categories

arose, they were constantly refined as more data was

collected and analyzed. Then, for each category, we

developed and defined its properties and dimensions,

allowing us to "differentiate a category from other

categories and give it precision" (Strauss and

Corbin, 1998, p. 117). Properties are particular

attributes of a category; dimensions delineate a

continuum along which a property can be located.

For example, participants discussed aspects of their

personal learning preference (category), which had

an attribute of control of learning or locus of control

(property). However, this property can vary from

completely self-directed or internal to completely

other-directed or external. This Grounded-Theory

approach to analysis kept us focused on the data,

helping us to form well-developed categories while

keeping a lookout for newly emerging ideas.

To increase the credibility of our findings, we

used several types of triangulation--multiple

methods, multiple sources of data, and multiple

investigators (Merriam, 2009). Interview and

observational data supported and were used to check

each other. Additionally, member checking helped

to ensure credibility. Each interview was an

opportunity to clarify and expand upon the

developing themes; and during the final interview,

we asked each participant specifically to comment

on our interpretation of their previous interview

responses and their classroom activities. Our aim

was to build in triangulation throughout the study,

weaving together data collection, analysis, and

verification (Miles and Huberman, 1994).

3 RESULTS

We found that the teachers' use of technology

reflected an interweaving of their beliefs about

teaching and technology with their accumulated life

experiences. In this section, we present three

categories (or themes) that emerged from the data

analysis and represent aspects of this relationship

between teacher and technology use. For each

theme, we briefly define it and then discuss it in

terms of its framework of properties and dimensions

(Table 1), using participants' quotes as further

illustration.

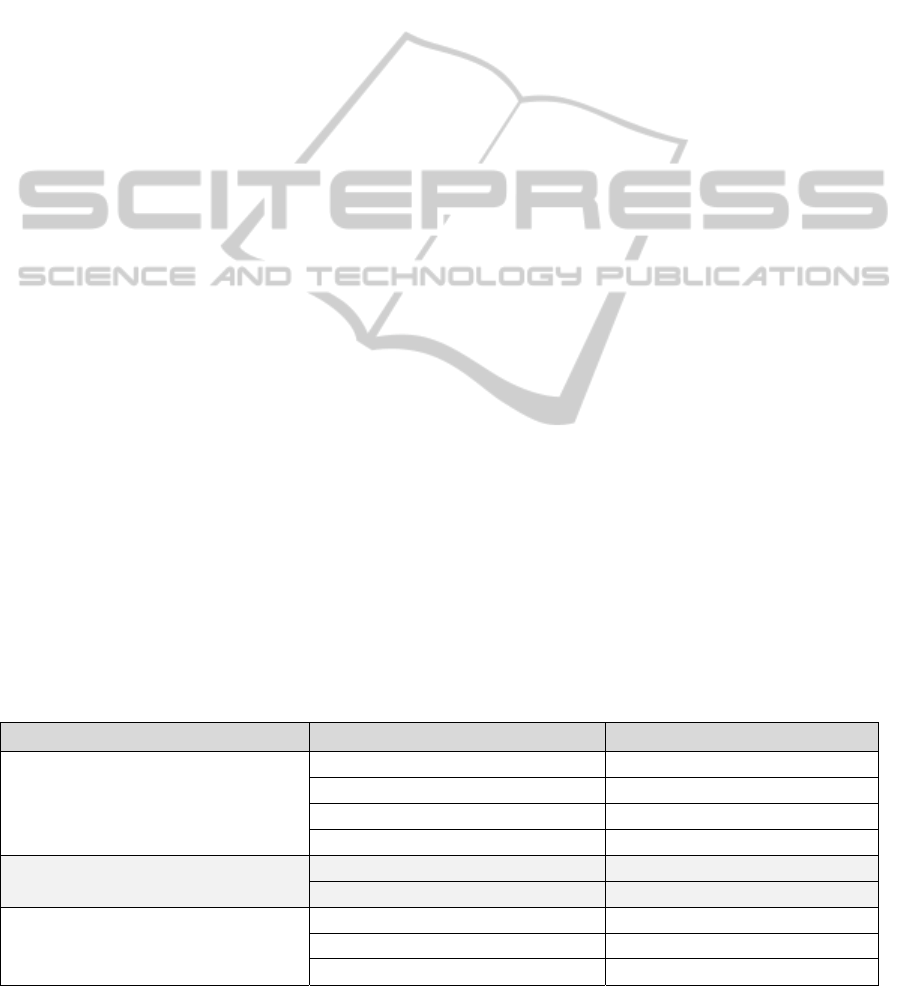

Table 1: Categories (factors) and their properties and dimensions.

Category Property Dimension

Personal Learning Preference

Locus of control External - Internal

Locus of responsibility External - Internal

Organization Freeform - Structured

Atmosphere Calm - Chaotic

Teaching Philosophy

Role of teacher Lecturer - Facilitator

Role of student Passive - Active

Perception of Technology

Personal value Practical - Entertaining

Educational value Narrowing - Expanding

Impact on teaching Restricting - Enhancing

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

130

3.1 Personal Learning Preference

One theme that emerged was personal learning

preference. We defined personal learning preference

as the teacher’s self-described way that she or he

learns best, both in and out of formal settings.

Outside formal settings, learning may be pursued

because of personal interest or belief that what is

learned might be of use personally or professionally.

The learner determines the pace and setting as well

as what and how learning occurs. In contrast,

formal settings involve planned learning in which

someone other than the learner structures the

learning goals, environment, content and process.

Each teacher gave various examples of how they

learned in both types of settings, with both teachers

speaking of learning independently. For example,

Mr. Aspen described how he would learn to use new

software: "I would just look online until I found

something that would be a nice tutorial." Ms. Beech

was similarly independent: "I spread out at my

kitchen table, I take a book, and I go at it." The

teachers also emphasized the personal nature of

learning and the need to “own” one’s learning. Ms.

Beech explained, “In my mind, it seems to me that

learning is a personal thing. People can guide you as

best they can but individually you have to make it

your own.” Mr. Aspen also felt that individuals

needed to personalize their own learning: “I think

it’s really important that they learn what works for

them.” Both teachers saw

the control of and

responsibility for learning residing internally, within

the learner, allowing individuals to make choices

about when and how they learned.

However, despite agreeing on the importance of

learner responsibility and independence, there were

some basic differences in their personal methods for

learning. Mr. Aspen described a technology-oriented

and multi-method process:

My hierarchy is written tutorial, picture-

based tutorial, video tutorial. So I would

probably start working my way down until I

found what I wanted. I’ve never been able to

sit though a lecture and take notes and then

understand what’s going on by those notes. I

have to do multiple things.

In contrast, Ms. Beech described her preference for

traditional, written materials and a more focused

approach: "I used to love reading IBM manuals, God

in heaven, I longed for it, I did, because you could

read it and you could understand." She also shared

her dislike of online tutorials and "help" options

with “snippets of this and snippets of that,”

describing them as “appalling.” For both teachers,

the ability to choose how they organized their

learning (internal locus of control) was important,

but the actual organization varied significantly, with

one being more structured and the other being more

freeform.

There were also differences in the physical

learning environment preferred by each teacher. Ms.

Beech described needing quiet, more controlled

surroundings: "Sometimes things will pop off the

page, and so you need to stop and ponder it. I don’t

learn in chaos." In contrast, Mr. Aspen described a

more chaotic learning environment: "I do all my

work sitting on the couch at the coffee table with a

dog running between my legs and [the] TV on." So,

again, the teachers acknowledged the importance of

having internal control over their learning

environment, choosing the atmosphere that suited

them best. One teacher preferred a very calm and

structured atmosphere, while the other was

comfortable studying in a more disordered setting.

Finally, we noted that the teachers’ learning

preferences also showed up in their opinions of

professional training. Neither teacher is a fan of

traditional professional development, particularly for

learning about technologies. Mr. Aspen preferred to

‘tinker’ rather than participate in formal training on

how to use technology tools. Ms. Beech described

her frustration with the rapid pace of professional

development on technologies:

You’ve got some of the worst training, in

my opinion, because people who run the

seminar will say ‘do this, do this, do this’

and you want to say ‘for real?’ And then

you’re supposed to be expert in that.

The traditional professional development format,

with its tendency to have a more external locus of

control, didn’t meet their desire to be in control of

their own learning (i.e., to choose when and how to

learn). They had a need for autonomy and to learn in

an environment with which they were comfortable.

3.2 Teaching Philosophy

A second theme concerned each teacher’s personal

teaching philosophy. We defined this as the

teacher’s personal beliefs about how teaching and

learning occur combined with examples of how the

teacher puts these beliefs into practice when

teaching. Both teachers spoke at length about what

should happen in the classroom and what they did to

optimize teaching and learning. Both valued direct

interaction between teacher and students, usually in

the form of meaningful discussion or dialogue

surrounding questions or problems. Ms. Beech

UnderstandingFactorsInfluencingTeachers'UseofTechnologiesinTeachingSTEM

131

acknowledged that she did a lot of talking when

teaching, but not as lecture: “My teaching style is

probably to talk, but talk with the students. I like

interacting with them, I just do. You’ve got to stop,

pause, and discuss.” Mr. Aspen saw interaction as an

opportunity for questions: "I want some dialogue

with students along the way, allowing students to

ask more questions.”

Often, the purpose of this dialogue was to assess

a student's level of understanding and to elicit a

student's thinking processes, making them visible to

both teacher and student. Ms. Beech's approach to

teaching very much emphasized this:

You’ve got to talk about what got written so

that the teacher can be assured that the

students are getting where they need to be. I

need to know what they know. We could be

going on and on, and I’m thinking that things

have been communicated and are well

understood. Then you start talking to ‘em

and you realize that that whole boat was

missed! So those are opportunities that you

get to find out where they are. For me, it

takes interaction because the room is full and

you got people at different levels of interest

and different levels of preparedness.

Although more teacher-centered in appearance, her

role in the class discussion was very purposeful, and

she did not see herself as a lecturer.

When observing teaching sessions, whether in

the STEM classroom or the traditional classroom,

we saw Ms. Beech continually using questioning to

engage with students (teacher asking students,

students asking teacher) with lots of give and take

occurring between the teacher and the students.

Through her interactive style, she made sure all

students were included and accountable for what

was being taught. Similarly, Mr. Aspen stated:

"Asking more questions to figure out where we need

to go is a lot of how I am.” Both teachers felt that

students should be actively engaged in the classroom

activities and in their learning.

Additionally, each teacher saw their role as one

of facilitator or guide, providing critical structure

and direction to the students' learning experiences.

Ms. Beech referred to one of her classes as "more of

a seminar type thing," with her guiding class

discussion to elicit student thinking and assess

student understanding. Mr. Aspen specifically

referred to himself as a facilitator and coach:

I want to be engaged with them, have them

be the primary speakers and me be a

facilitator of education rather than an expert

of education. What’s been helping me

through a lot of things and helping a lot of

the students through is providing set and

clear, established expectations for what they

need to do. Today I wrote what you need to

do to get every bit of points right on that

board (points to board in front of classroom)

at the beginning of class, showing them,

okay, this is what we are going to be doing,

more of a learning coach than a knowledge

giver.

For both teachers, meaningful classroom interaction

was the key to successful teaching and learning.

Interestingly, Mr. Aspen's philosophy evolved

somewhat during the period of the study, changing

from unsure and idealistic to more confident and

realistic. During our final interview, he described

this shift in his teaching:

I am teaching differently than I used to

because it used to be a very binary system. I

was really way too far on the progressive

side, or I was way too far on the traditional

side. I tried to do something, and if it didn’t

work out like I wanted it to, I would fall back

to this ‘lecture and do problems from a

worksheet’ sort of thing.

As an early-career teacher, Mr. Aspen was still

finding the best way to meld the ideals of his

teaching philosophy with the realities of the

classroom.

During the time of the study, we saw changes in

the way Mr. Aspen taught, which he attributed to

moving from being a novice teacher to a more

experienced teacher. Early in his first year of

teaching, he stressed: “I am very much not a

traditional style teacher. I have found it a lot easier

to put the work on students rather than me.”

However, following his third year of teaching, he

admitted that his philosophy had changed:

I am no longer under the assumption that I

can change education for kids overnight...

I’ve actually gotten more traditional. I

wouldn’t say that I am a traditional teacher,

though. I think I lecture more and introduce

concepts more at the beginning of class than

I used to because I found that kids are more

familiar with that [approach] and receptive to

it and so I try to pick out specific concepts

that, if I know they’re going to run into this

problem within the first five to ten minutes

of them working with something, then I try

to address it up front.

As Mr. Aspen gained teaching experience, he began

to think differently about what works best in the

classroom and made small modifications to his

teaching practice in both classrooms.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

132

3.3 Perception of Technology

A third theme concerned each teacher’s perception

of technology. We defined this as the way a teacher

views and uses technology, both personally and

professionally. Both teachers viewed technology as

a tool, something that could be potentially useful in

and out of the classroom. Each teacher spoke of the

many practical advantages to using technology. Mr.

Aspen believed that knowing how to use technology

is essential in today’s world. He considered himself

tech-savvy, regularly using the Internet and

technology gadgets in his daily life, and is a self-

proclaimed ‘geek.’ Ms. Beech also valued

technology, but emphasized its more practical uses:

I really do appreciate cell phones because

there are a lot of needs in an emergency. I

used to have to write things by hand, and

when I started [working] it was punch cards.

Then it evolved... so technology, in that

sense, is a good thing, and it really has

helped the countries of the world. I think

you get so much productivity with

technology.

For Ms. Beech, technology’s value resided more in

its impact on safety and efficiency and less in its

potential for entertainment and education.

In addition to personal entertainment, Mr. Aspen

described how technology helped him to be more

productive, adaptable, and flexible in his classroom:

I was going to have an end of year survey for

my students and get feedback from them, and

I was actually able to just say, ‘Okay,

everyone go get an iPad.' I was able to make

a Google form in the time that it took them to

go get that and come back, and I just did it

that way. It’s nice to have that adaptability.

A lot about it [technology] is the flexibility

that you have. If I need some kids to just

swing over and start working on something

online, or on a computer, or a quick self-

check quiz, or a Kahn Academy lesson or

something like that, it’s really nice to have

the flexibility to do that.

Technology expanded his options in the classroom

and enhanced his teaching.

While Mr. Aspen embraced the use of

technology in teaching, Ms. Beech questioned its

role in teaching and stressed that she will not use it

“just for the sake of using it.” She worried that

technology has been too widely and too quickly

accepted:

I get the sense that there’s a lot of looking

outside of current resources to access a lot of

stuff that apparently is effective. I think

technology is a good thing. I have not

bought into technology being a replacement

for [the] teacher; I just haven’t bought into

that it replaces interaction with students. I

really don’t want to imply that that’s a

general perspective on technology, but with

the constant hype about using technology, I

think that you’re left with the impression that

if you’re not using technology, then there’s

definitely something wrong with you. I think

that if the teachers work at it, and if the

technology can facilitate more learning in

some way, then it’ll be a good thing.

While Ms. Beech questioned the use of technology

in teaching, she was aware that, with effort, it could

be used effectively. The main drawback in learning

to use technology effectively in the classroom,

according to Ms. Beech, was the time it required to

find good resources that could be integrated in a way

that promoted student learning. She recognized

technology's limitations:

What happens, I think, is that when you rely

too much on technology, kids will learn a

pattern and they will not understand the

pattern; they cannot transfer it. So what I

need to know is how much technology do we

get that actually focuses on the ability to

transfer?

She perceived technology as potentially narrowing

students' learning experiences, but sensed that

teachers could make the difference and ensure that

technology facilitated learning instead.

4 DISCUSSION

The results of this study highlight the impact that

teachers’ experiences, beliefs, and perceptions have

on their use of technology. Both teachers in this

study were presented with a new and very unusual

teaching environment: a high-tech STEM classroom

designed for flexibility. In addition to this new

room, the teachers were provided with a technology

support specialist, customized professional

development, and the support of the school's

administration, as a lack of these items has been

identified as a major factor influencing teacher's

adoption of technology (Bingimlas, 2009; Buabeng-

Andoh, 2012; Hew and Brush, 2007). Both teachers

made use of this environment, bringing their

students into the STEM classroom on a regular basis

and using its new technologies. Over the course of

three years, as the teachers became familiar with the

UnderstandingFactorsInfluencingTeachers'UseofTechnologiesinTeachingSTEM

133

innovations, we noticed small changes in how they

used technology in their classroom teaching. For

example, Ms. Beech had students teach the class

about using graphing calculators, incorporating

some peer instruction into her normally teacher-

centered classroom. Mr. Aspen, initially using as

much technology as often as possible, incorporated

more direct instruction into his class by the end of

the study, stating that technology needed to serve

him and not the other way around. However, in spite

of these changes, we did not observe any significant

changes in the way technology was used by either

teacher or in the way that they taught. Each

remained true to their own core beliefs and

viewpoints—beliefs and viewpoints that drove their

use of technology and that appeared to be largely

shaped by their life experience and personal learning

experiences. This contrasts with findings reported by

Becker and Ravitz (1999) that found a strong

relationship between technology use and

pedagogical change among secondary science

teachers. On the other hand, research by Ertmer et

al. (2012) supports this alignment between personal

beliefs and technology integration.

Several other researchers have studied the effect

that teachers' beliefs have on their teaching

behaviors and their adoption of innovations (Ertmer,

2005; Hew & Brush, 2007; Ricardson-Kemp & Yan,

2003; Wozney, Venkatesh & Abrami, 2006). For

example, in a study of factors influencing adoption

of inquiry learning curriculum in science, Roehrig,

Kruse, and Kern (2007) reported that teachers’

beliefs combined with school support played an

important role in how a new science curriculum was

implemented. Furthermore, teachers’ practices and

beliefs are formed based on aspects of the teacher’s

background, including professional background,

content and pedagogical knowledge, knowledge of

technology, beliefs about teaching, classroom

activities, classroom and school level environments,

teacher’s technology self-efficacy, and professional

activities (Holden and Rada, 2011; Mishra and

Koehler, 2006; OECD, 2009). Our findings are

consistent with results of these studies and

contribute to the international literature on factors

influencing teachers’ use of technologies (Afshari et

al., 2009; Baek, et al., 2008; Buabeng-Andoh, 2012;

OECD, 2009).

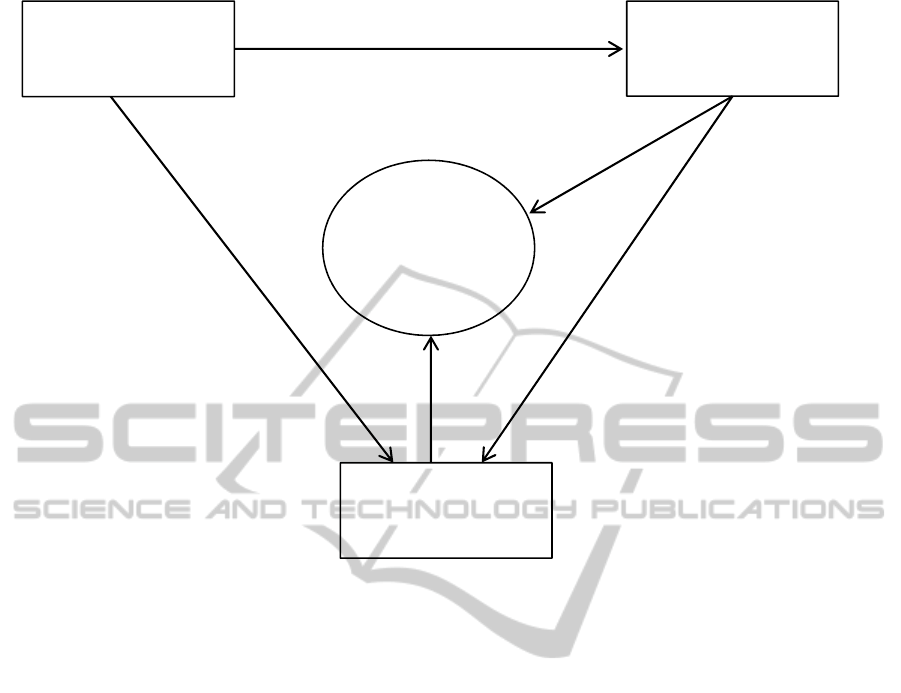

The three themes that emerged from the data

create an interrelated set of factors influencing the

teachers' use of technologies (Figure 1). The first

theme, the teachers' personal learning preferences,

guided their teaching both with and without the use

of technology, influencing both teaching philosophy

and perception of technology. As self-described

independent learners, the teachers also encouraged

their students to be the same, to ask and pursue their

own questions and take responsibility for their own

learning. Often, as in the case of Mr. Aspen, this

independence showed up in the differentiation that

was built into the lessons, allowing students to work

at their own pace and on their own projects using the

technology of their choosing when possible. It also

came out in the strong belief by both of the teachers

that students have to "make learning their own." No

matter what happens in the classroom, the

responsibility and control of learning resides within

each student. In many ways, both teachers teach

with technology in the way they preferred to learn.

The second theme, teaching philosophy, is

strongly tied to what teachers believe to be best in

education. We observed elements of each teacher's

teaching philosophy directly impacting their use of

technology in both the traditional and STEM

classrooms. For example, each teacher believed in

the importance of verbally interacting with students-

-not lecturing them, but talking with them. Neither

teacher saw him or herself as a traditional lecturer;

talking was used very purposefully to elicit student

thinking and to gauge student understanding. Mr.

Aspen regularly took advantage of the numerous

projection options in the new classroom to project

individual student work on computers and engage

students in discussion about that work. Even Ms.

Beech, who considered herself more of a knowledge

giver than facilitator, expected her students to take

an active role in their learning. When she began

using PowerPoint slides in classes, she used them as

a basis for class discussion. Both teachers

encouraged students to ask questions, listen

carefully, and thoughtfully discuss the material.

They valued student-student interaction as well as

student-teacher interaction, and both teachers

expected their students to become critical thinkers

and independent learners. Even though the teaching

environment changed and technologies were

introduced into it, the philosophy of teaching still

guided teaching practice.

The new STEM classroom was equipped with a

variety of new technologies, and so it is not

surprising that the teachers' perception of technology

emerged as a prominent theme in our analysis,

directly influencing the classroom use of

technologies and, at the same time, being influenced

by both personal learning preference and teaching

philosophy. Previous researchers have identified the

influence of teachers’ beliefs about technology on

their decisions on when and how to use technology

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

134

Figure 1: Relationships among factors influencing teachers' use of technologies.

in teaching (Ertmer, 2005; Teo, 2011). Although

both teachers saw value in technology (e.g.,

increased productivity, efficiency, flexibility), Mr.

Aspen's all-out embracing of technology--even the

playful aspects--contrasted strongly with Ms.

Beech's more skeptical view. This wide difference

in viewpoint is in line with their very different

background experiences. Ms. Beech's years of

working "behind the scenes" with large computer

systems gave her a very particular lens through

which to view education's current emphasis on

bringing new technologies into the classroom. She

believed that “technology dictates behaviour." She

explained, "If you use technology, you’re going to

use the technology the way that a designer’s built it."

At one point, she referred to today’s technologies as

“toys.” On the other hand, Mr. Aspen comes to

technology with more of a consumer viewpoint,

perhaps better able to appreciate the entertainment

aspects of technology.

Although the teachers were expected to utilize

the technologies in the new classroom, the school

administration gave them the freedom to decide how

they would use the technologies and how quickly

they would adopt each technology. The teachers

were given the chance to assimilate the innovations

into their own teaching practices according to their

own teaching philosophy, learning preferences, and

perceptions of technology. Professional

development occurred in progressive stages, with

the teachers deciding on the format, when it would

occur, and what technologies it would address. It has

been suggested that this type of autonomy not only

plays a critical role in motivation and creativity, but

is actually a basic human need (Pink, 2009). Jones

and Dexter (2014) found that formal professional

development activities organized at an

administrative level often ignores the experiences

and knowledge of teachers and stifles their creativity

in using technology in teaching.

Regarding the perception of technology, we

noted a generational difference in the participants.

Mr. Aspen showed much more confidence towards

and willingness to embrace technology than Ms.

Beech. While research conducted by Wang et al.

(2014) did not find this difference, this observation

is supported by a recent Pew survey (2013) that saw

differences in teachers responses to technology

based on age group. According to the survey,

teachers under the age of 35 were more likely than

teachers age 55 and older to say they were “very

confident” about using new digital technologies (64

percent vs. 44 percent). However, although this

same survey reported that the oldest teachers (age 55

Personal Learning

Preference

Teaching

Philosophy

Perception of

Technology

Use of

Technologies in

Teachin

g

UnderstandingFactorsInfluencingTeachers'UseofTechnologiesinTeachingSTEM

135

and older) were more than twice as likely as their

colleagues under age 35 to say their students know

more than they do about using the newest digital

tools (59 percent vs. 23 percent), our participants

both believed that their students were much more

tech-savvy than they were.

5 IMPLICATIONS

The results of this study have implications for those

seeking to maximize teachers’ adoption of

technologies into the learning environment. First,

teachers’ beliefs—formed and solidified over years

of life experience—direct much of what happens in

the classroom. These beliefs are deeply tied to

teaching philosophy and perception of technology,

making them a core factor in classroom technology

adoption. Professional development activities that

recognize and acknowledge the role such beliefs

play by including strategies that help teachers

expand their existing teaching philosophy to include

technology use and that help teachers extend their

perception of technology are more likely to be

successful than activities that do not. However, it is

important to realize that modifying beliefs and

perceptions take time, and thus, so do change and

the adoption of innovations.

In addition to beliefs, teacher autonomy may

play an important role in the successful adoption of

innovations. Both teachers in this study valued being

in control of their own learning and having the

opportunity to determine what they would learn,

when they would learn it, and at what rate. It seems

that their personal learning preferences along with a

strong internal sense of “what is best” for teaching

and learning influenced their classroom practices.

Therefore, strategies that acknowledge and work

with teachers' different learning preferences,

combined with allowing teachers to decide their best

learning path, may promote the best outcomes

during any type of change process. Successful

adoption of technology requires attention to teacher

differences and plenty of options for teacher choice.

6 LIMITATIONS & FUTURE

RESEARCH

Although one should always be cautious in

generalizing findings, our results are consistent with

several other studies concerning teachers' adoption

of technology and reaction to change (Ertmer, 2005;

Ertmer and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010; Hew and

Brush, 2007; OECD, 2009; Reid, 2014; Richardson-

Kemp and Yan, 2003; Teo, 2011). Furthermore, the

case study design provides enough detail to allow

other researchers to decide upon its transferability.

While our study focused on only two teachers, our

participants were very different in almost every

respect: demographics, personal and professional

experience, and in most personal beliefs about

technology and pedagogy. This maximum

participant variability provided us with rich data and

allowed us to capture a wide range of ideas and

themes while reducing the chance of missing an

important concept.

Since we studied a complex, active environment

for over three years, it's not surprising that a variety

of outside events impacted what we observed in

these classrooms. Over the course of the study,

many changes took place in the school and in the

district. For example, a new director was hired early

in the study and initiated the PLTW program as well

as other initiatives. New after-school programs were

implemented, many of them STEM-related. Mr.

Aspen gained two years of valuable teaching

experience, significant for a beginning teacher and

most likely accounting for the evolution of his

teaching practices over the course of the study. A

longitudinal project is subject to these issues, but

since the process of change can be lengthy, it was

critical for us to spend enough time with our

participants.

Finally, further research could address the role

autonomy plays in the adoption of technology and

the modification of teaching practices. Although

some authors have discussed autonomy in relation to

teacher job satisfaction and professionalism

(Common, 1983; Pearson and Moomaw, 2005),

there have been relatively few studies that examine

its role in the change process specifically when the

change involves technology. While Ernest (1994)

discussed teacher beliefs and their role in autonomy

and the enacting of a new mathematics curriculum,

additional research focusing on the impact of teacher

autonomy in the adoption of innovations and on the

modification of teaching practices is still needed.

REFERENCES

Afshari, M., Bakar, K. A., Luan, W. S., Samah, B. A., and

Fooi, F. S., 2009. Factors affecting teachers’ use of

information and communication technology.

International Journal of Instruction, 2(1), pp. 77-104.

Angers, J., and Machtmes, K., 2005. An ethnographic-

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

136

case study of beliefs, context factors, and practices of

teachers integrating technology. The Qualitative

Report, 10(4), pp. 771-794.

Baek, Y., Jung, J., and Kim, B., 2008. What makes

teachers use technology in the classroom? Exploring

the factors affecting facilitation of technology with a

Korean sample. Computers & Education, 50, pp. 224-

234.

Becker, H. J., and Ravitz, J., 1999. The influence of

computers and internet use on teachers’ pedagogical

practices and perceptions. Journal of Research on

Computing in Education, 31(4), pp. 356-384.

Bingimlas, K. A., 2009. Barriers to the successful

integration of ICT in teaching and learning

environments: A review of the literature. Eurasia

Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology

Education. 5(3), pp. 235-245.

Buabeng-Andoh, C., 2012. Factors influencing teachers’

adoption and integration of information and

communication technology into teaching: A review of

the literature. International Journal of Education and

Development using Information and Communication

Technology. 8(1), pp. 136-155.

Byrom, E., and Bingham, M., 2001. Factors influencing

the effective use of technology for teaching and

learning: Lessons learned from the SEIR_TEC

Intensive Site Schools, 2

nd

Ed. (2001). SouthEast

Initiatives Regional Technology in Education

Consortium (SEIR_TEC).

Common, D. L., 1983. Power: The missing concept in the

dominant model of school change. Theory into

Practice, 22(3), pp. 203-210.

Corbin, J. M., and Strauss, A., 1990. Grounded theory

research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria.

Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), pp. 3-21.

Ernest, P., 1989. The impact of beliefs on the teaching of

mathematics. In P. Ernest. ed. 1989. Mathematics

teaching: The state of the art. London: Falmer Press.

pp. 249-254.

Ertmer, P.A., 2005. Teacher pedagogical beliefs: The final

frontier in our quest for technology integration?

Educational Technology Research and Development,

53(4), pp. 25-39.

Ertmer, P. A., and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., 2010.

Teacher technology change: How knowledge,

confidence, beliefs, and culture intersect. Journal of

Research in Technology Education, 42(3), pp. 255-

284.

Ertmer, P.A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., Sadik, O.,

Sendurur, E., and Sendurur, P., 2012. Teacher beliefs

and technology integration practices: A critical

relationship. Computers and Education, 59(2), pp.

423-425.

Flores, A., 2007. Examining disparities in mathematics

education: Achievement gap or opportunity gap? The

High School Journal, 91(1), pp. 29-42.

Hall, G.E., and Hord, S. M., 2011. Implementing change:

Patterns, principles and potholes. (3

rd

ed.). Boston,

MA: Pearson Education.

Hanson, K., and Carlson, B., 2005. Effective access:

Teachers use of digital resources in STEM teaching.

Available:

<http://www2.edc.org/GDI/publications_SR/Effective

AccessReport.pdf>.

Hew, K. F., and Brush, T., 2007. Integrating technology

into K-12 teaching and learning: Current knowledge

gaps and recommendations for future research.

Educational Technology Research and Development,

55, pp. 223-252.

Holden, H., and Rada, R., 2011. Understanding the

influence of perceived usability and technology self-

efficacy on teachers’ technology acceptance. Journal

of Research on Technology in Education, 43(4), pp.

343-367.

Jones, H. M., and Dexter, S., 2014. How teachers learn:

the roles of formal, informal, and independent

learning. Educational Technology Research and

Development, 62, pp. 367-384.

Margolis, J., Estrella, R., Goode, J., Holme, J.J., and Nao,

K., 2008. Stuck in the shallow end: Education, race

and computing. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Merriam, S. B., 2009. Qualitative research: A guide to

design and implementation. San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M., 1994. Qualitative

data analysis (2

nd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publishers.

Mishra, P., and Koehler, P. A., 2006. Technological,

pedagogical, content knowledge: A new framework

for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record,

108(6), pp. 1017-1054.

Mumtaz, S., 2000. Factors affecting teachers’ use of

information and communications technology: A

review of the Literature. Journal of Information

Technology for Teacher Education, 9(3), 319-342.

Nugent, G., Barker, B., Grandgenett, N., and Adamchuck,

V., 2010. Impact of robotics and geospatial technology

interventions on youth STEM learning and attitudes.

Journal of Research on Technology in Education,

42(4), pp. 391-408.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD), 2009. Creating effective teaching and

learning environments: First results from teaching and

learning international survey. Available:

http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/creatingeffectiveteach

ingandlearningenvironmentsfirstresultsfromtalis.htm.

Patton, M. Q., 2002. Qualitative evaluation and research

methods (3

rd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publishers.

Pearson, L. C., and Moomaw, W., 2005. The relationship

between teacher autonomy and stress, work

satisfaction, empowerment and professionalism.

Educational Research Quarterly, 29(1), pp. 38-54.

Pew Research Center, 2013. How teachers are using

technology at home and in their classroom.

Washington, DC: Author. Available:

<http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teachers-and-

technology.>

UnderstandingFactorsInfluencingTeachers'UseofTechnologiesinTeachingSTEM

137

Pink, D., 2009. Drive: The surprising truth about what

motivates us. New York: Riverhead Books.

Reid, P., 2014. Categories for barriers to adoption of

instructional technologies. Education and Information

Technologies, 19, pp. 838-407.

Richardson-Kemp, and Yan, W., 2003. Urban school

teachers’ self-efficacy, beliefs and practices,

innovation practices and related factors in integrating

technology. Society for Information Technology and

Teacher Education International Conference

Proceedings, Vol. 2003, No. 1, pp. 1073-1076.

Roehrig, G. H., Kruse, R. A., and Kane, A., 2007. Teacher

and school characteristics and their influence on

curriculum implementation. Journal of Research in

Science Teaching, 44, p. 883-907.

Stephen, M. L., 1997. A study of the effects of differences

among students’ and teachers’ perceptions of

computers and experiences in a computer-supported

classroom. PhD dissertation. Saint Louis University,

St. Louis, MO.

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. M., 1998. Basics of qualitative

research: Techniques and procedures for developing

grounded theory (2

nd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Teo, T. (2011). Factors influencing teachers’ intention to

use technology: Model development and test.

Computers & Education, 57(2011), pp. 2432-2440.

Wang, S. K., Hsu, H.Y., Campbell, T., Coster, D. C., and

Longhurst, M., 2014. An investigation of middle

school science teachers and students use of technology

inside and outside of classrooms: Considering whether

digital natives are move technology savvy than their

teachers. Educational Technology Research &

Development, 62(6), pp. 637-662.

Wozney, L., Venkatesh, V., and Abrami, P. C., 2006.

Implementing computer technologies: Teachers’

perceptions and practices. Journal of Technology and

Teacher Education, 14(1), pp. 173-207.

Yin, R. K., 2009. Case study research: Design and

methods. (4

th

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publishers.

Zhao, Y., and Frank, K.A., 2003. Factors affecting

technology uses in schools. An ecological perspective.

American Educational Research Journal, 40(4), pp.

807-840.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

138